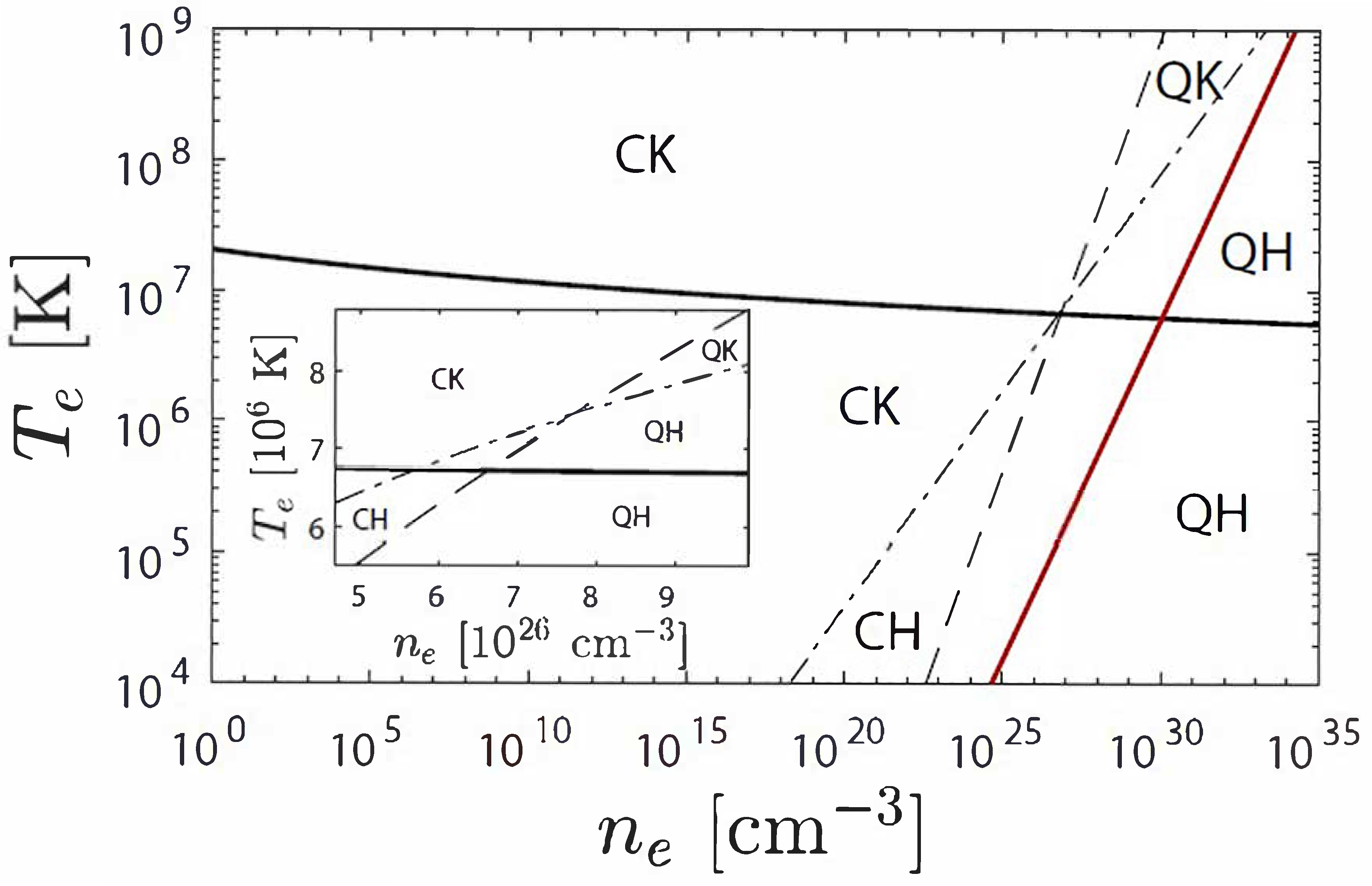

In many space plasmas including solar-type stars the plasma parameter

, defined by the electron-electron elastic collision rate

and the electron plasma frequency

is many orders of magnitude smaller than unity for reported electron temperatures

and number densities

(Figure 1 in [

1]). These systems are classified as collision-poor or kinetic Vlasov plasmas in which the interactions with electromagnetic fields characterized by

strongly dominate the collision rate

Unless otherwise noted the units are in basic cgs and Kelvin. Elastic Coulomb as well as Møller and Bhabha scattering therefore cannot maintain thermal Maxwell particle distribution functions in these plasmas in contrast to collision-dominated plasmas [3,4].Efficient Maxwellization of these plasmas allow the often used theoretical description of these systems with magnetohydrodynamical (MHD) equations derived from taking velocity moments of the underlying particle kinetic equations. Here the temperature enters via the ideal or adiabatic equations of state.

Observationally, however, there is clear evidence for the presence of thermal particle distribution functions in cosmic collision-poor plasmas. This is strongly supported by in-situ plasma measurements of the solar wind. The solar wind plasma is the only cosmic plasma where detailed in-situ satellite observations of plasma properties are available [5,6,7]. The plasma parameters of the solar wind are similar to the fully ionized phases of the interstellar gas, so that the same plasma physical processes leading to thermalization should also operate in these systems. Although the detailed plasma relaxation processes are not understood [8], the measured electron and proton distribution functions have been modeled with bi-Maxwellian velocity distributions with different temperatures along and perpendicular to the ordered magnetic field direction , which are special cases of velocity-anisotropic particle distribution functions. The WIND/-SWE satellite [6,7] has measured finite magnetic field fluctuations only within the colored rhomb-shaped configuration in the parameter plane defined by the temperature anisotropy and the parallel plasma beta . Magnetic field fluctuations only occur close to the isotropy and equipartition values and , respectively. The solar corona, the partially ionized and fully ionized phases of the interstellar medium in our and other galaxies, as well as active galactic nuclei, the intergalactic medium, the intracluster gas and cosmic voids also are collision-poor plasmas.

It is the purpose of this work to propose an efficient kinetic Maxwellization process in collision-poor unmagnetized plasmas relying on the interaction with the noncollective fluctuations having no dispersion relation. The collective modes, where the complex frequency is related to the real-valued wave vector , in unmagnetized plasmas with isotropic particle distribution have been well studied before including their backreaction on the charged plasma particles. Besides the undamped () superluminal electromagnetic waves that cannot resonantly interact with the particles, three damped (with negative ) modes exist: the longitudinal electrostatic waves [9], in electron-ion-plasmas the longitudinal ion sound waves, and transverse aperiodic (with ) fluctuations [10,11], which oscillate in space but do not propagate. In particular no growing eigenmodes are possible in these plasmas [10,12,13,14,15,16].

Alternatively, the noncollective fluctuations have unrestricted complex frequencies, and in the following we investigate their generation and back reaction on the particles. It is demonstrated that the quasilinear interactions of charged plasma particles with the spontaneously emitted non-collective fluctuations provide an alternative mechanism to produce thermal particle distribution functions in collision-poor space plasmas. Every plasma spontaneously emits electromagnetic fluctuations due to the random motions of its charged particles causing subsequent particle-fluctuation interactions. These are described by quasilinear transport theory if the ratio of particle number density fluctuations is small compared to the averaged particle density. We follow the derivation of the general quasilinear Fokker-Planck kinetic equation for the gyrophase-averaged plasma particle distribution functions in magnetized plasmas ([17] – hereafter referred to as paper I) making no restrictions on the energy of the particles and on the frequency of the electromagnetic fluctuations. The derivation is based on Maxwell equations for the electromagnetic fields and on the Klimontovich equation [18] for the charged particles accounting for discrete particle effects and spontaneous emission of fluctuations. The monograph [19] provides an excellent introduction into the combined kinetic theory although this approach adopts nonrelativistic particle energies throughout.

Our investigation here will be fully relativistic. As shown in paper I the inclusion of discrete particle effects breaks the dichotomy of nonlinear kinetic plasma theory divided into the test particle and the test fluctuation approximation because it provides expression of electromagnetic fluctuation spectra in terms of the plasma particle distribution functions. The resulting quasilinear transport equation can be regarded as a determining nonlinear equation for the time evolution of the particle distribution function. The general case of magnetized plasmas has been investigated before in paper I, but has lead to very involved final expressions. In its most general form this nonlinear equation is rather involved and complicated. Therefore it is appropriate to study simpler plasma configurations such as unmagnetized plasmas which is the purpose of the present manuscript. According to Eqs. (78)–(81) of paper I, the general gyrophase-averaged quasilinear transport equation for the spatially uniform phase space distribution function

of sort

a with charge

and mass

in spherical momentum coordinates

reads

with the gyrophase-averaged drag and momentum diffusion terms

respectively, involving the Fourier-Laplace transformed stochastic force

and free-particle Klimontovich particle density

of sort

a, while

accounts for sources and sinks of particles.

Here we are primarily interested in the isotropic equilibrium distribution functions

determined by the balance of momentum loss of plasma particles by spontaneous emission (described by the drag term) and the momentum diffusion of plasma particles caused by the electromagnetic fluctuations, respectively. Moreover, in stationary plasmas one is interested in temporal averages, where the averaging time

must be greater than the correlation time of fluctuations for this average to be independent of

[20,21]. This leads to

with

For isotropic and gyrotropic distribution functions

. In the case of unmagnetized plasma considered here, we orient the wave vector along the cartesian

z-direction

. Likewise, one obtains

with

. Also the Maxwell operator only has diagonal elements with

and

with the longitudinal and transverse dispersion functions

with the plasma frequency

,

, and

. For the stochastic force one notices with

and

that

and

, The Fourier-Laplace transformed electric field components are given by the solution of the wave equation (65) of paper I, in this case

where we used [19,22]

for the Fourier-Laplace transformed two-time correlation function of free-streaming uncorrelated particles in unmagnetized plasmas. With

the only non-vanishing electric field correlation functions are

and

given according to Equation (6) by

upon introducing the complex phase speed

, i.e.,

, the integrals

and

with

. Both correlation functions (8) are completely determined by the isotropic particle distribution function

. The index

b instead of

a indicates that in general the electric fluctuations entering the quasilinear momentum diffusion coefficient

for particles of sort

a can be generated both by these particles themselves (

), referred to as self-confinement, and/or by other (

) charged particle populations in the considered plasma.

The drag and momentum diffusion terms are evaluated in detail in Supplementary Section A [23] as

and a corresponding, more lengthy, expression (A.12) for

, where we made use of Equation (8). It is important to emphasize that the derived drag term and momentum diffusion term (via the electric field correlation functions (8)) are based on the identical two-time correlation (9). The drag term (9) and the momentum diffusion term (A.12) are first important results of the present investigation.

Next, we focus on the self-confinement case

and the high-frequency limit

so that we ignore the influence of damped (negative

) collective modes on the particle dynamics and approximate the dispersion functions as

. It is well known [10,12,14,15,16] that in unmagnetized plasmas with isotropic particle distribution functions no growing collective modes with positive

exist. In the high-frequency limit and self-confinement case (

) the drag and momentum diffusion terms (9) and (A.12) then read

with

where

, provided

. Within the same limit, where

holds, the

is continuous and analytic at all points in the complex

z-plane and requires no analytic continuation. The frequency integrals

appearing in

and

are calculated as

and

, respectively (Supplementary Sections B,C), leading to the momentum-independent

and

. The particle equilibrium condition (3) then reads in the high-frequency limit

with the positively valued, dimensionless ratio

With the requirement

the Equation (14) is solved by the relativistic Boltzmann-Jüttner distribution function (

denotes a modified Bessel function)

obeying the normalization requirement

. With this solution (16) one obtains

with

which evaluates to

where

[24]. Relation (15) then becomes

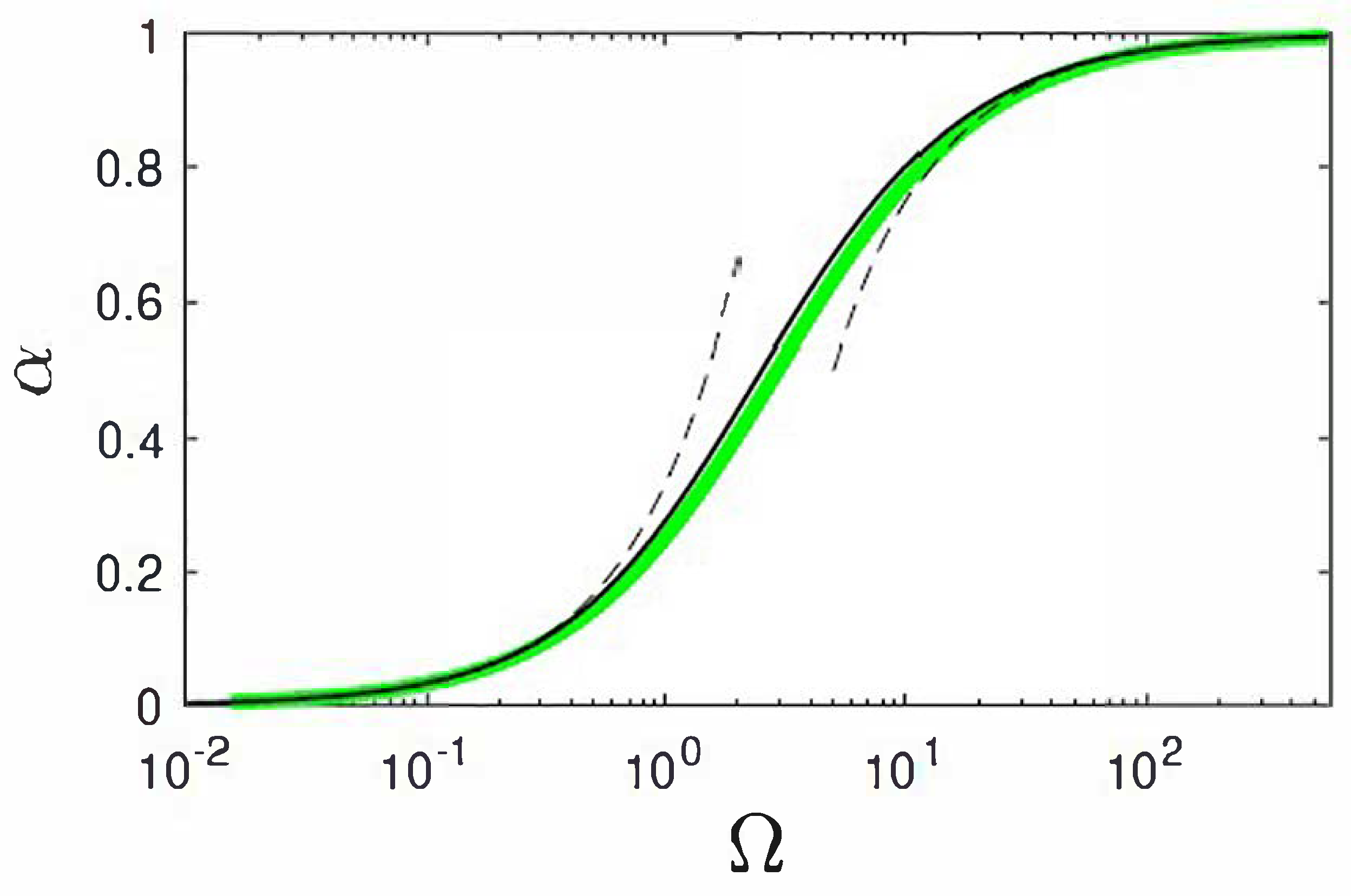

Most noteworthy

cannot get larger than unity (

Figure 1). Consequently, solutions of Equation (17) are only possible if its right-hand side is also smaller than unity. The constant

defines the plasma temperature by

, because for large values of

the distribution function (16) reduces to the nonrelativistic Maxwellian distribution

.

The equilibrium distribution function (16) also results without the self-confinement assumption, however, with a different depending on the origin of the electric field fluctuations . This is particularly true for heavier plasma particles, such as protons, which undergo momentum diffusion in the electric field fluctuations generated by the lighter electrons. The mechanism is self-regulating: besides generating the Boltzmann-Jüttner equilibrium distribution function it also yields with Equation (17) a defining equation for the plasma temperature provided the maximum wavenumber is small enough. The maximum wavenumber has to be regarded as the only free parameter of the presented analysis. What complicates the issue is that itself can be temperature dependent.

Employing a standard choice of

[19], involving the atomic classical electron radius

, together with the inverse Debye length

, the resulting temperature-density relation

lies outside the parameter regime for the applicability of the classical kinetic theory (Supplementary Section D). For dilute plasmas we adopt

being given by the inverse Debye length (for a motivation see Supplementary Section E, see also reference [26] therein). Here we identify the minimum wavenumber with

, where

L denotes the size of the considered astrophysical system. Equation (17) for electrons then reduces with

to

where

depends only logarithmically weakly on

,

and size of the system scaled in kpc

. With

this Equation (18) is solved in terms of the non-principal Lambert function as (

Figure 2)

This result agrees remarkably well with the observed intracluster gas temperatures of

in the unmagnetized outer parts of clusters of galaxies [27,28], where cooling effects by free-free photon emission can be neglected. For dilute plasmas almost independently of the density value the equilibrium temperature is

(

Figure 2). The estimate is valid for

when the electron de Broglie wavelength is smaller than the average interparticle distance corresponding to thermal energies larger than the Fermi energy [

1]. The characteristic relaxation time scale is given by

. It is particularly short at high densities and remains momentum-independent for nonrelativistic electrons.

In conclusion, it has been demonstrated that an efficient thermalization mechanism in collision-poor unmagnetized plasmas results from the competition between the momentum losses of plasma particles by spontaneous emission of high-frequency non-collective fluctuations and the momentum diffusion of these particles in their self-generated fluctuating electric field. The mechanism is self-regulating but the resulting relation is severely influenced by the adopted maximum wavenumber of the fluctuations. The mechanism provides nearly independently of the plasma number density for super-miles long fluctuation wavelengths Such very long wavelengths make it difficult to identify them in particle-in-cell plasma simulations of limited size., and is applicable to plasmas with densities below . Future studies should investigate the influence of collective eigenmodes on this mechanism avoiding the high-frequency approximation.

References

- G. Manfredi, How to model quantum plasmas, in Topics in Kinetic Theory, Fields Institute Commun., Vol. 46, edited by T. Passot, C. Sulem, and P.-L. Sulem (American Mathematical Society, Providence, Rhode Island, United States, 2005) p. 263.

- Unless otherwise noted the units are in basic cgs and Kelvin.

- P. Helander and D. J. Sigmar, Collisional Transport in Magnetized Plasmas (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K, 2006).

- G. P. Zank, Transport Processes in Space Physics and Astrophysics (Springer, New York, USA, 2014).

- J. C. Kasper, A. J. Lazarus, and S. P. Gary, Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, 20 (2002).

- S. D. Bale, J. C. Kasper, G. G. Howes, E. Quataert, C. Salem, and D. Sundkvist, Magnetic fluctuation power near proton temperature anisotropy instability thresholds in the solar wind, Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 211101 (2009).

- B. A. Maruca, J. C. Kasper, and S. D. Bale, What are the relative roles of heating and cooling in generating solar wind temperature anisotropies?, Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 201101 (2011).

- T. A. Bowen, B. D. Chandran, J. Squire, S. D. Bale, D. Duan, K. G. Klein, D. Larson, A. Mallet, M. D. McManus, R. Meyrand, et al., In situ signature of cyclotron resonant heating in the solar wind, Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 165101 (2022).

- R. Schlickeiser, M. M. Martinovic, and P. H. Yoon, Phys. Plasmas 28, 052110 (2021).

- T. Felten and R. Schlickeiser, Spontaneous electromagnetic fluctuations in unmagnetized plasmas. vi. transverse, collective mode for arbitrary distribution functions, Phys. Plasmas 20, 104502 (2013).

- R. Schlickeiser and P. H. Yoon, Quasilinear theory of general electromagnetic fluctuations in unmagnetized plasmas, Phys. Plasmas 21, 092102 (2014).

- I. B. Bernstein, Waves in a plsma in a magnetic field, Phys. Rev. 109, 10 (1958).

- C. S. Gardner, Bound on the energy available from a plasma, Phys. Fluids 6, 839 (1963).

- N. A. Krall and A. W. Trivelpiece, Principles of Plasma Physics (McGraw-Hill, New York, United States, 1973).

- S. P. Gary, Theory of Space Plasma Microinstabilities (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., 1993).

- R. Schlickeiser and M. Kneller, Relativistic kinetic theory of waves in isotropic plasmas, J. Plasma Phys. 57, 709 (1997).

- R. Schlickeiser and P. H. Yoon, Quasilinear theory of general electromagnetic fluctuations including discrete particle effects for magnetized plasmas: General analysis, Phys. Plasmas 29, 092105 (paper I) (2022).

- Y. L. Klimontovich, Kinetic theory of nonideal gases and nonideal plasma (Pergamon, Oxford, U.K., 1982).

- P. H. Yoon, Classical Kinetic Theory of Weakly Turbulent Nonlinear Plasma Processes (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., 2019).

- M. Born and E. Wolf, Principles of Optics: Electromagnetic Theory of Propagation. Interference and Diffraction of Light (Pergamon Press, Oxford, United States, 1965).

- D. H. Froula, S. H. Glenzer, N. C. Luhmann, and J. Sheffield, Plasma Scattering of Electromagnetic Radiation (Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011).

- R. Schlickeiser and P. H. Yoon, Spontaneous electromagnetic fluctuations in unmagnetized plasmas I: General theory and nonrelativistic limit, Phys. Plasmas 19, 022105 (2012).

- See supplemental material at [url will be inserted by publisher] for drag and momentum diffusion terms, the complex ω-integration, evaluation of frequency integrals, dense stellar plasmas, and comment on kmax.

- M. Abramowitz and I. A. Stegun, Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables (Dover Publications, New York, 1972).

- J. N. Bahcall, Neutrino Astrophysics (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., 1989).

- R. Schlickeiser, U. Kolberg, and P. H. Yoon, Primordial plasma fluctuations. i. magnetization of the early universe by dark aperiodic fluctuations in the past myon and prior electron–positron annihilation epoch, Astrophys. J. 857, 29 (2018).

- A. C. Fabian, P. E. J. Nulsen, and C. R. Canizares, Cooling flows in clusters of galaxies, Nature 310, 733 (1984).

- C. L. Sarazin, X-ray Emission from Clusters of Galaxies (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., 1988).

- Such very long wavelengths make it difficult to identify them in particle-in-cell plasma simulations of limited size.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).