1. Introduction

Experimental diffusion studies in multicomponent solids have so far been carried out with the assumption of constant partial molar volumes of components [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. However, most of the real systems are non-ideal, in which case the partial molar volumes of individual components are dependent on the composition. Thus, there is invariably a net volume change associated with the interdiffusion process. In a typical infinite diffusion couple, this leads to a non-zero velocity of the two terminal ends as well as a contribution to the interdiffusion flux at every plane in the diffusion couple from the non-Fickian drift associated with the volume change. This has been ignored so far due to the assumption of constant partial molar volume. Recent work by the present author [

17,

18] has highlighted the significance of considering composition dependent partial molar volumes in the interdiffusion analysis of experimental diffusion profiles developed in binary as well as multicomponent diffusion couples.

The method for extraction of interdiffusion coefficients from the experimental concentration profiles was first proposed by Boltzmann [

19]. Matano first applied the Boltzmann’s analysis to solid-solid binary diffusion couple [

20]. The crucial aspect of Matano’s analysis was the determination of the interdiffusion coefficients with respect to the location of initial contact plane, which in turn was determined with the simple mass balance. The method, which is popularly known as Boltzmann-Matano (BM) method, was primarily proposed for and applicable to binary systems and, for the assumption of constant molar volumes. Sauer and Freise [

21] were the first ones to derive an expression for binary interdiffusion coefficient in terms of relative concentration variables as obtained from experimental diffusion profiles for the case of composition dependent partial molar volumes. Wagner [

22] and de Broeder [

23] derived the similar equation for binary interdiffusion coefficient with different approaches. Various other authors [

24,

25,

26] also attempted to address the problem of varying partial molar volumes, again, in binary interdiffusion analysis. A detailed review of all these methods is presented in [

27]. The main success of Sauer-Freise [SF] equation [

21] is that it does not need the location of the initial contact plane. However, the equation is applicable for binary analysis only. Roper and Whittle [

28], without giving any reasoning for the case of molar volume variation, proposed that the SF equation can be extended to even multicomponent systems.

Manning extensively worked on developing analytical relations between tracer diffusion coefficients and interdiffusion coefficients through the thermodynamic factors in multicomponent systems [

29]. Manning’s model was applicable to the case of constant molar volume. Paul [

30] has recently extended Manning’s model to include varying molar volumes. Manning’s model is essentially based on the assumption of random mixing of components, which means the binding energies and the effects of neighboring atoms on the jump frequencies are not considered. Most importantly, the model predictions of interdiffusion coefficients require the knowledge of thermodynamic factors as well as tracer diffusion coefficients at the desired composition. There are several restrictions on producing experimental tracer diffusivity data as it requires the use of radioactive isotopes. Although thermodynamic databases are now available for several systems, they are mostly based on extrapolating thermodynamic information from unary and binary (and in rare cases ternary) to higher order systems. Hence, the thermodynamic factors extracted from these usually have large errors, which are further propagated into predicted interdiffusion coefficients. Experimentally determined interdiffusion coefficients, on the other hand, inherently consist of all such contributions viz. vacancy wind effects, thermodynamic interactions and correlation effects. Hence, the experimental determination of interdiffusion coefficients from diffusion couple experiments currently has no matching alternative.

“Interdiffusion flux” is an important quantity in the phenomenological analysis of multicomponent diffusion. Dayananda [

7,

31] was the first one to emphasize the significance of flux determination from diffusion profiles. Dayananda and coworkers also developed various methodologies to utilize the fluxes in determining various phenomenological aspects of multicomponent diffusion including interdiffusion coefficients, average effective interdiffusion coefficients, diffusion depths and various constraints on the interdiffusion process [

7,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Dayananda also provided a graphical proof for validity of SF equation to ternary and higher order systems but only for the assumption of constant molar volume [

31]. So far, there is no attempt in the literature to check whether the expression for interdiffusion flux as discerned from SF or Wagner’s analysis is valid in the case of multicomponent diffusion with varying partial molar volumes. Still, it has been (wrongly) considered to be valid by numerous multicomponent diffusion studies over the years. Hence, the objective of the present work is to analytically derive the expression for interdiffusion flux in a multicomponent diffusion couple with the composition dependent partial molar volumes. Earlier, all such attempts were for binary systems only. However, the method used in the present study is valid in general for multicomponent systems with varying partial molar volumes. It is shown that the binary SF equation is not valid for multicomponent systems with composition dependent partial molar volumes. The newly derived equations are further applied to determine interdiffusion fluxes in three single-phase FCC Ni-Cr-Al diffusion couples reported in the literature [

8,

9].

2. Derivation of New Expression for Multicomponent Systems with Composition Dependent Partial Molar Volumes

2.1. Frame of Reference

In the interdiffusion analysis, it is of utmost importance to recognize and state the frame of reference that one is dealing with [

35,

36,

37,

38]. In a multicomponent system with composition dependent partial molar volumes, the continuity equation is applicable only in a stationary or lab-fixed frame of reference [

35,

36,

37,

38] and is expressed as.

where

is the interdiffusion flux in moles/cm

2-s measured with respect to the stationary frame (

),

is the concentration of the component

i in moles/cm

3,

x is the distance coordinate and

t is the time. Two of the most important frames of reference often used in the literature are the number fixed frame (

) and the volume fixed frame (

). In

, the fluxes are measured with respect to the local center of total number of moles of all components such that the net flux in number of moles per unit area per unit time is zero across all planes at all times [

37]. In

, the fluxes are measured with respect to the local center of total volume such that the net flux expressed in volume of the material is zero across all planes at all times [

37]. The local center of number of moles and the local center of volume move with velocities

and

respectively, with respect to the stationary frame. Both

and

are functions of

x and

t.

By the definitions of

and

, the interdiffusion fluxes in these frames,

and

respectively, are constrained by the equations [

35,

36,

37,

38]:

and

where

is the partial molar volume of the component

i.

The interrelation between

and

can be written as

and that between

and

is given by

Summing Equation (4) over all components, using constraint in Equation (2) and knowing the relation for molar volume (

),

one can write [

35,

36,

37]

Similarly, multiplying Equation (5) with

, then summing it over all components, using Equation (3) and knowing the relation,

one can write [

35,

36,

37,

38]

Substituting for

from Equation (7) into Equation (4),

However,

where,

denotes the mole fraction of

i.

Similarly, from Equations (5) and (9), one obtains

Equations (12) and (13) will be used in further analysis to get expressions for and as determined directly from the experimental concentration profiles of a multicomponent diffusion couple.

2.2. Component Velocities and Fluxes at the Terminal Ends of a Diffusion Couples

In an infinite diffusion couple, the compositions at the two terminal ends are unaffected. Thus, the interdiffusion fluxes in

and

are zero in the two terminals, where the composition gradients are zero. However, in a non-ideal system, which most systems are, the partial molar volume of a component changes with composition and hence, the diffusion is associated with a net volume change, leading to net motion of each terminal end. Thus, the interdiffusion fluxes measured in

are not zero in the two terminals. Let

and

denote the concentrations of component

i in the left and right terminal alloys, respectively. In each of the terminals, the interdiffusion fluxes (

) of the individual components are constant. Also, the average atom velocity should be same for all components in each terminal [

22]; let them be

and

in the left and the right terminals respectively. Let

and

denote the interdiffusion fluxes of components

i and

k in

in the left terminal alloy. Since,

and

, one can write for any two given components

i and

k,

Based on Equation (11), multiplying both sides of Equation (14a) by

, the molar volume of left terminal alloy, one can also write

where,

and

are mole fractions of components

i and

k respectively in the left terminal alloy.

Similarly, in the right terminal alloy, with

and

being the mole fractions of

i and

k in it, one can write

The significance of Equations (14 a-b) and (15 a-b) will be clearer in the analysis to follow.

2.3. Interdiffusion Flux in Number Fixed Frame in Terms of Molar Concentrations

In an infinite diffusion couple, a given composition is a function of the Boltzmann parameter

λ, which is given by [

19]

where,

is the reference plane in a stationary frame, which is typically considered to be the initial weld plane. Thus, Equation (1) can be written as

Substituting for

and

based on Equation (16) we get

Integrating Equation (18) between

and the desired location

x in the diffusion zone at a fixed time

t,

where,

and

are the interdiffusion fluxes in R

0 at

and at

x respectively. Similarly, we can write for any other Component

k,

Multiplying Equation (19a) by

and subtracting Equation (19b) multiplied by

from it,

However, the term in second square bracket on right hand side of Equation (20) is zero on account of Equation (14b). Thus, one can write

On a similar line, integrating Equation (18) between

x and

, we get for components

i and

k respectively,

Multiplying Equation (22a) by

and subtracting Equation (22b) multiplied by

from it,

However, the term in second square bracket on right hand side of Equation (23) is zero on account of Equation (15b). Thus, one can write

Let,

denote the concentration of a component

i at the desired location

. Now, multiplying Equation (21) by

and adding Equation (24) multiplied by

to it one obtains,

provided

, where,

The mathematical treatment applied from Equation (19a) through Equation (28) can also be extended to any pair of component

i with any component

m other than

i and

k to get

provided

. Summing all such equations written for each pair of the component

i and a component

k other than

i, i.e., Eq (25a), (25b) etc., and using Equation (12), one can write,

provided any of

. Equation (29) gives an exact expression for interdiffusion flux measured in number fixed frame in a multicomponent diffusion couple with composition dependent partial molar volumes.

2.4. Interdiffusion Flux in Volume Fixed Frame in Terms of Molar Concentrations

Based on Equation (11), Equations (25a) and (25b) can be written as

((30b)

Multiplying (30a) by

and adding to it (30b) multiplied by

,

Thus, writing Equation (30a) for each pair of the component

i with a component

k other than

i, multiplying throughout by

and then summing them all and, using Equation (13), we get

Equation (32) gives an exact expression for interdiffusion flux measured in volume fixed frame in a multicomponent diffusion couple with composition dependent partial molar volumes.

2.5. Interdiffusion Fluxes ( and ) in Terms of Relative Concentration Variables

The relative concentration variable at any position

x,

, is generally defined as [

21,

22]

In terms of

, the expression for

i.e., Equation (29) can be reduced to the form

where,

and provided, any of the

. The derivation of Equation (34) from Equation (29) is presented in Appendix A of

Supporting Data File. On a similar line, it can be shown that the expression for

, Equation (32), can be reduced to the form

provided, any of the

. It should be noted that Equations (29) and (32) are equivalent to Equations (34) and (35) respectively. Equations (34) and (35) are independent of the coordinate system used for the analysis. Hence, Equations (29) and (32) are also independent of the coordinate system. Thus,

x0 in Equations (29) and (32) can be replaced with any convenient coordinate in the experimental diffusion profiles.

2.6. Interdiffusion Fluxes for Binary Systems

In a binary system of Components 1 and 2, it can be easily shown that

(say) and that the determinants in Equation (29) reduce to the form

,

and

. Thus, Equation (29) for a binary system reduces to

Equation (36) and (37) show that

as expected in a binary system. Further, Equation (34) and (35) can be shown to reduce for a binary system to

It should be noted that Equations (36) and (38) are equivalent. Also, the factor of

should not be ignored that is required for converting binary interdiffusion flux from

to

as observed from Equations (38) and (39). Although Sauer and Freise [

21] and Wagner [

22] did not explicitly list the equation for interdiffusion flux, the equation that can be discerned from the one proposed for binary interdiffusion coefficient by them is similar to Equation (38) in

RN or Equation (39) in

RV. We will refer to Equation (38) as SF equation as it has often been suggested to be valid for multicomponent systems too [

7,

28]. However, the analysis presented here clearly shows that the SF equation is not valid for ternary and higher order systems exhibiting composition dependent partial molar volumes. Based on Equations (38) and (39), it is easily discerned that the binary interdiffusion coefficient as suggested by Equation (14) of Wagner [

22], corresponds to the volume fixed frame of reference. For the assumption of constant molar volume though, Equations (38) and (39) are identical because all partial molar volumes are constant and equal to molar volume of the alloy.

2.7. Case of Multicomponent Diffusion with Constant Partial Molar Volumes

In the absence of data on partial molar volumes as functions of compositions in multicomponent systems, they are generally assumed constant for multicomponent diffusion analysis. In case of constant partial molar volumes, there is no net change in the volume after diffusion and hence, the two terminal ends do not move with respect to the stationary frame. Thus, both the number fixed frame and volume fixed frame coincide with the stationary frame leading to

(say) at any plane in an infinite diffusion couple. Since the interdiffusion fluxes at the two terminals i.e.,

and

are zero, Equations (19a) and (22a) can simply be written as

Equation (40) matches with the one derived by Dayananda and Kim [

7] and the superscript

CV in

denotes that it is applicable for the assumption of constant partial molar volume.

Further, it can be shown that (only) for the assumption of constant partial molar volumes, both Equations (34) and (35) can reduce to

It should be noted here that Equations (40) and (41) are valid in a multicomponent system but only for the assumption of constant partial molar volumes. For composition dependent partial molar volumes, the correct equations for interdiffusion fluxes in multicomponent systems are those given by Equations (29) and (34) in RN and, by Equations (32) and (35) in RV.

3. Application of New Equations to Determination of Interdiffusion Fluxes in Ni-Cr-Al Diffusion Couples

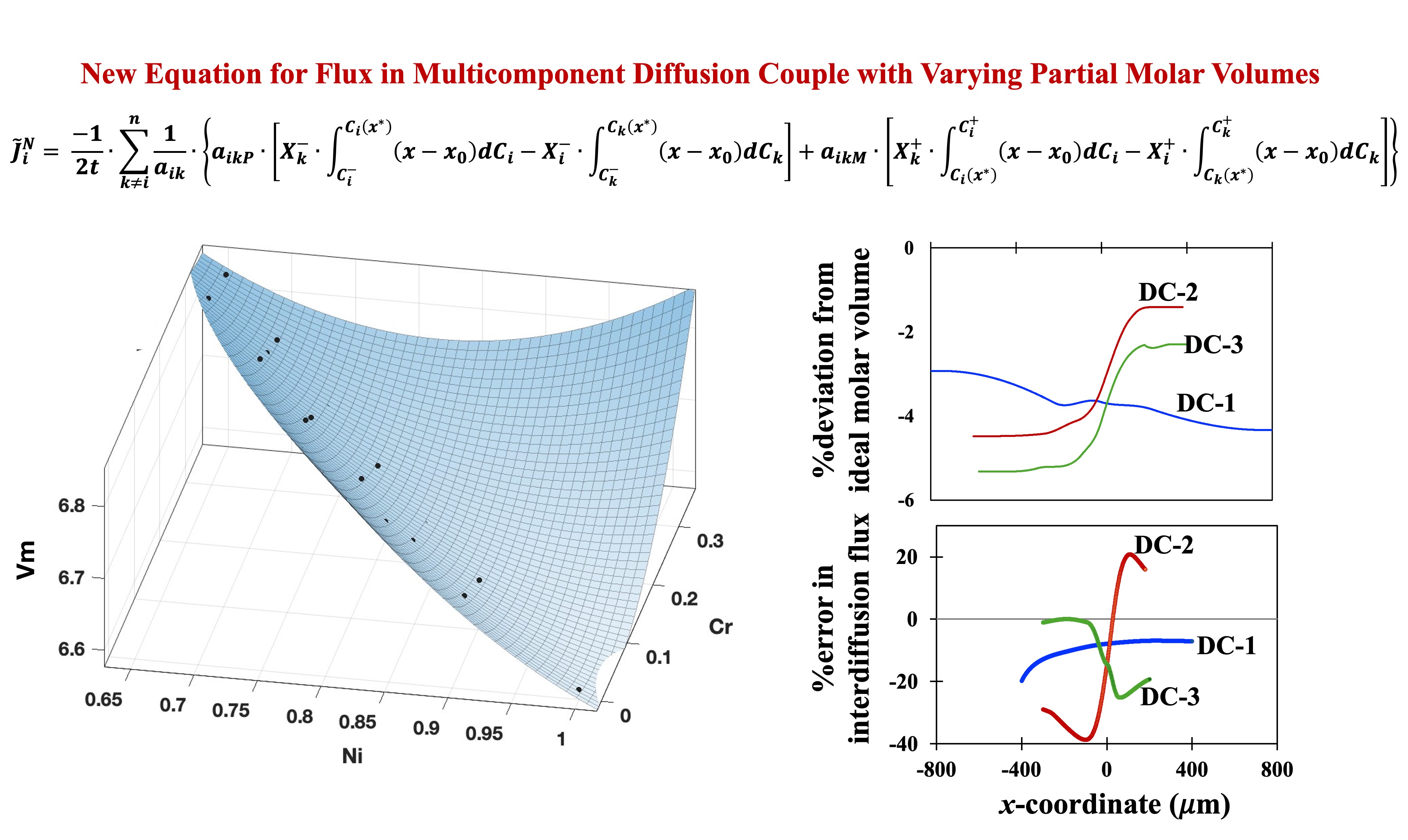

For applying the newly developed equations in the present work to a multicomponent system, it is essential to have extensive data on lattice parameters as function of composition available in the system. This would enable the determination of the molar volumes at various compositions as desired in the equations. Additionally, there should be data on diffusion profiles available in the literature. Ni-Cr-Al is one of the very few systems in which both the desired data are available and hence, it is used for demonstrating the application of newly developed equations in the present work.

The lattice parameters in FCC phase of the ternary Ni-Cr-Al systems were taken from the work of Taylor and Floyd [

39] as summarized in [

40]. The molar volumes were determined from the lattice parameters at several different compositions of the FCC phase and were fitted to a quadratic equation in the ternary composition space (

) as

where,

is in cm

3/mol and

and

are mole fractions of Ni and Cr respectively. The fitting of the molar volume data was carried out by the Curve Fitter module of Matlab and the constant in the quadratic equation was fixed to 10 for the fitting as it is approximately the molar volume of pure FCC aluminum. The tabular data on the molar volumes at various compositions and the 3-D plots of the molar volume versus composition based on Equation (42) are presented in

Table S1 and Figure S1 respectively in Appendix B of

Supporting Data File. The partial molar volumes of the individual components were evaluated as functions of compositions from Equation (42) with the procedure outlined by the present author in a recent work [

18] and the

supplementary file therein.

Nesbitt and Heckel [

8,

9] extensively worked on the interdiffusion analysis in FCC Ni-Cr-Al system by utilizing solid-solid infinite diffusion couples. However, their entire analysis was based on the assumption of constant molar volume. The experimental data from three of their reported diffusion couples were used in the present work for determination of interdiffusion fluxes by the application of the newly developed equations. The designations of the diffusion couples, their terminal alloy compositions, isothermal annealing temperatures and time as listed by Nesbitt and Heckel are presented in

Table 1.

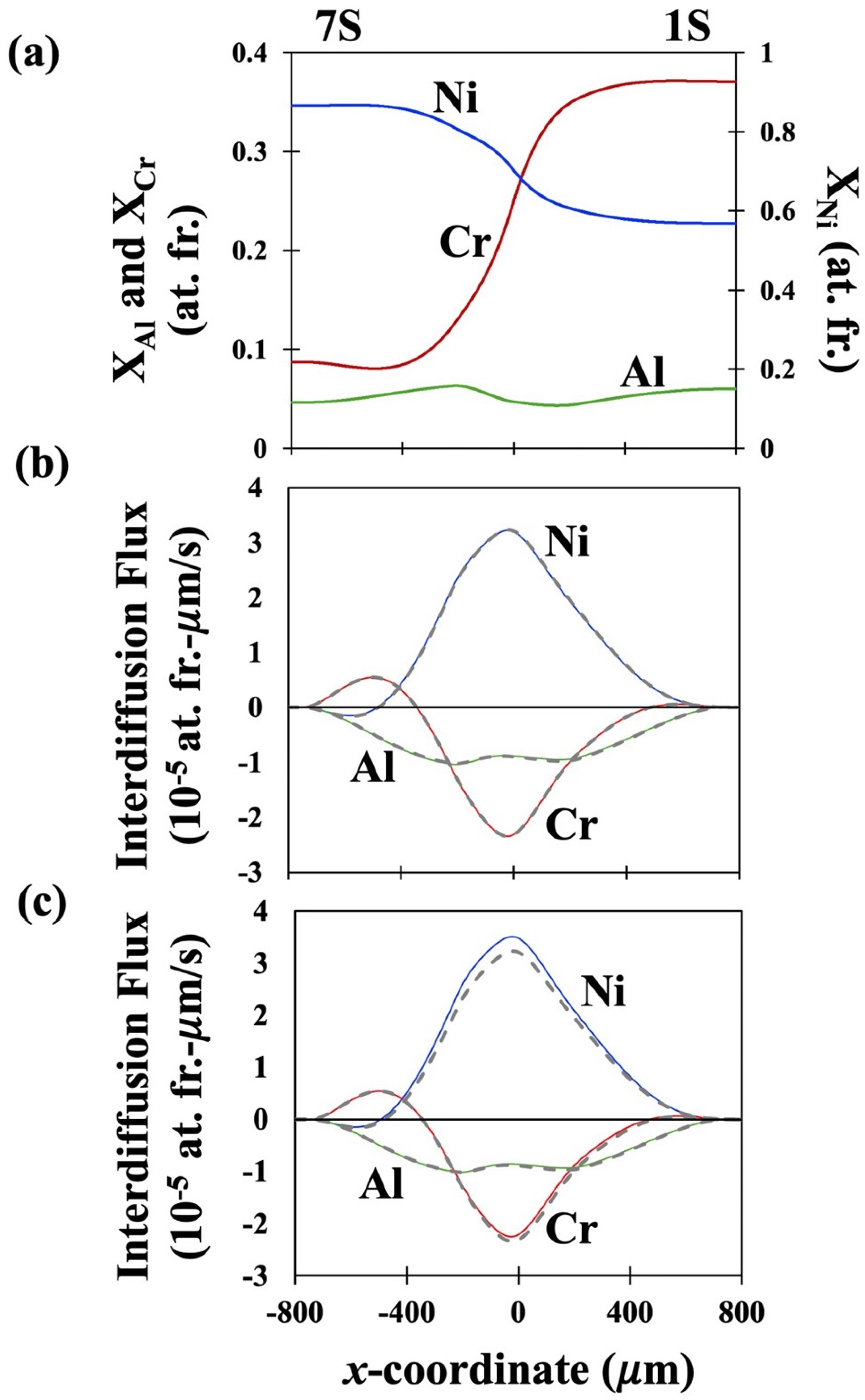

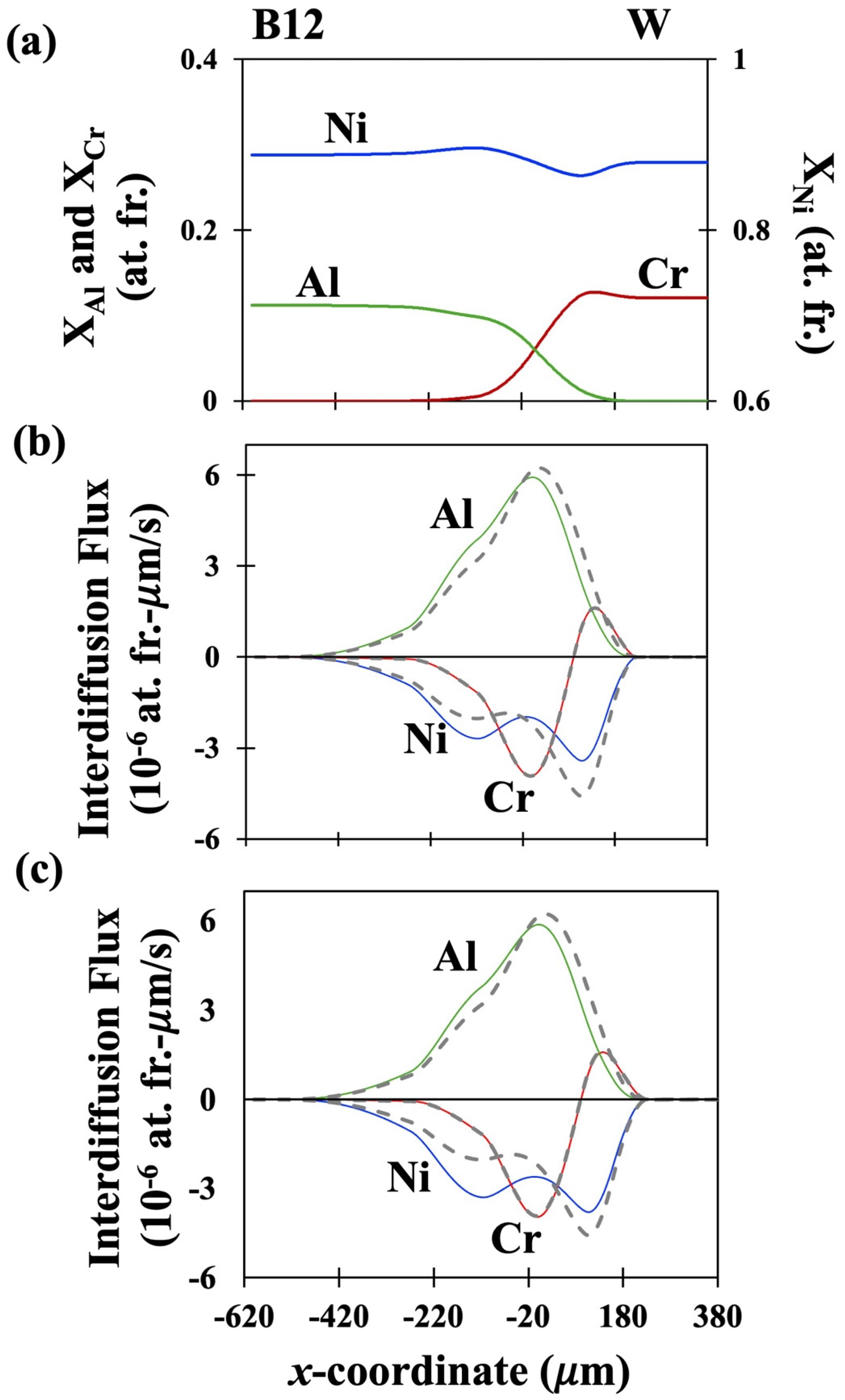

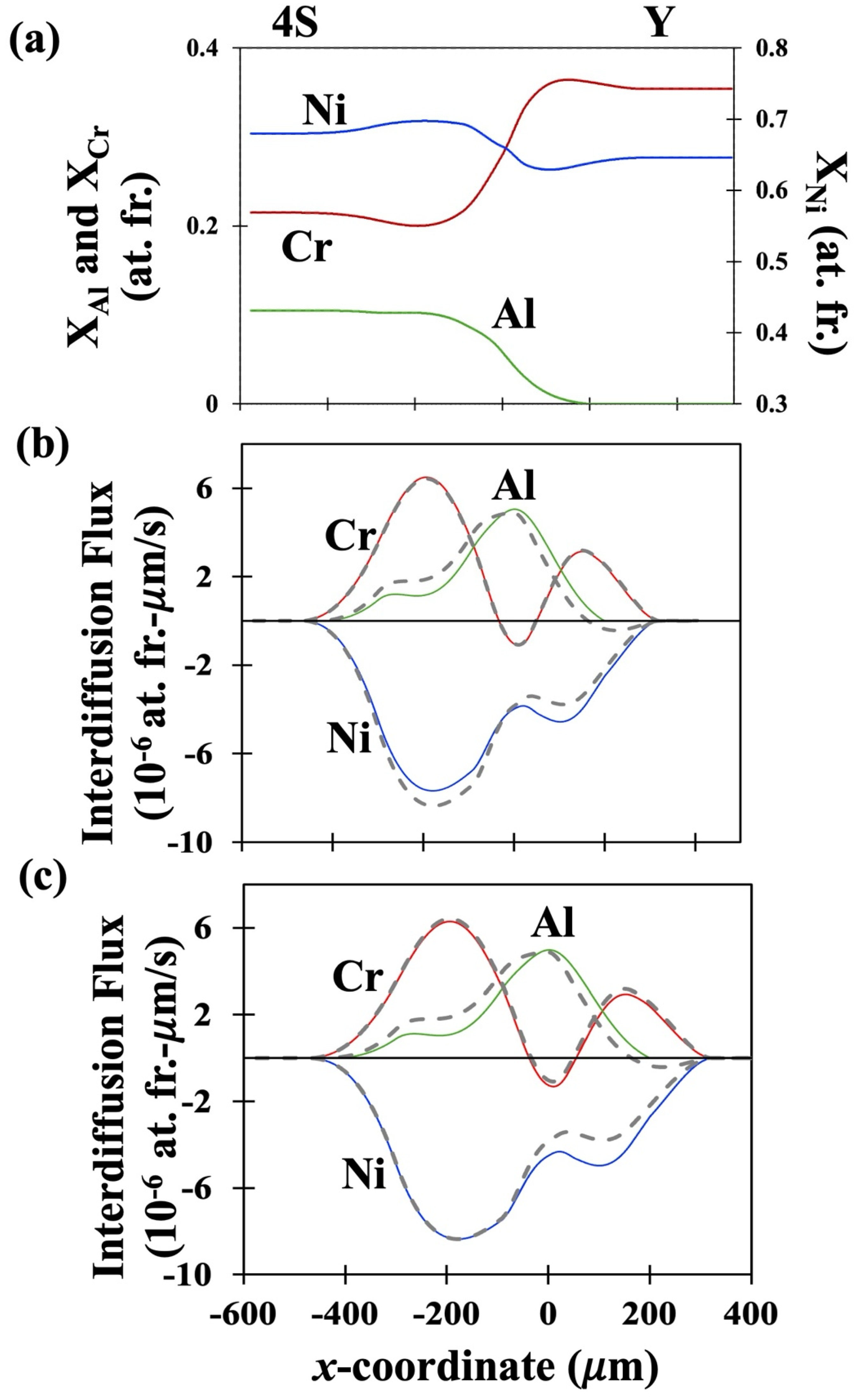

The concentration data for the three couples (DC-1, DC-2 and DC-3) were extracted from the concentration profiles presented in [

8,

9] by using a digital data-extraction software, DigitizeIt. The concentration data were then fitted with the computer program

MultiDiFlux, the working of which has been explained in various earlier works [

14,

16,

41]. The fitted concentration profiles of the couples DC-1, DC-2 and DC-3 are presented in

Figure 1a,

Figure 2a and

Figure 3a respectively. The interdiffusion fluxes in number fixed frame as determined using the newly derived equation, Equation (29) are presented as solid lines for the three couples in

Figure 1b,

Figure 2b and

Figure 3b respectively. Similarly, the interdiffusion fluxes in volume fixed frame as determined using the newly derived equation Equation (32) are presented in

Figure 1c,

Figure 2c and

Figure 3c as solid lines. The interdiffusion fluxes as determined by the Sauer-Friese equation, Equation (38), which has been shown here to be not correct for multicomponent systems with varying partial molar volumes, are shown as dashed lines for comparison. It can be seen from

Figure 1b that the values of

as determined from the newly developed equation, Equation (29) are almost similar to those determined by S-F equation, Equation (38) for all three components in DC-1. However,

Figure 2b and

Figure 3b show that, in DC-2 and DC-3, the two sets of values show large differences, especially for Ni and Al. A similar trend is observed from

Figure 1c,

Figure 2c and

Figure 3c for comparison of

as determined from the newly developed equation, Equation (32) and the flux determined form S-F equation, Equation (38) with the differences being slightly larger for

than for

. This is a critical observation as it shows that the S-F analysis is valid in multicomponent systems for determining interdiffusion fluxes only in the case of constant molar volumes. Its use for determining interdiffusion fluxes, in the multicomponent systems with composition dependent partial molar volumes should lead to errors in estimation of the fluxes. Such errors would be further propagated when the fluxes are used for evaluating interdiffusion coefficients leading to larger errors in the values of the latter.

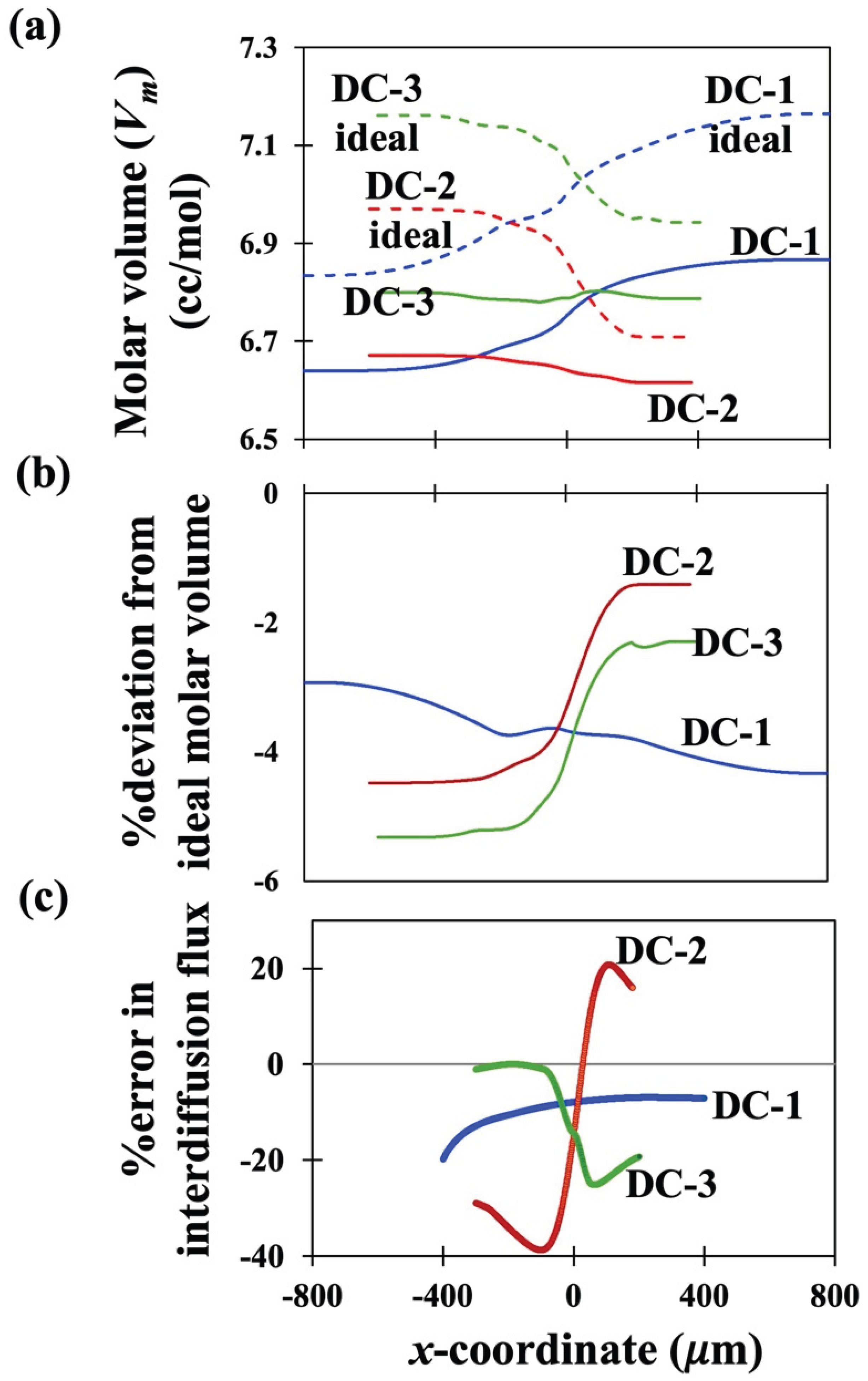

Figure 4a presents the variation of molar volumes in the diffusion zones of the three couples DC-1, DC-2 and DC-3 as represented by solid lines. Variation of ideal molar volume is also shown on

Figure 4a by dashed lines for the three couples. The deviation of the actual molar volume from ideal values (in %) is shown for all three couples in

Figure 4b.

Figure 4c presents the errors in the evaluation of interdiffusion fluxes of Ni, if determined by S-F formula, Equation (38) over the correct formula, Equation (32) derived in this work for all three couples.

Only Ni-fluxes are presented in

Figure 4c because Ni is seen to exhibit the largest errors of all three components. Since the errors involved with the end regions where the concentration gradients are approaching zero are generally large, only the errors in fluxes in the central part of the diffusion zones are presented in

Figure 4c. It can be qualitatively seen that the errors in the fluxes are larger for a given couple, if the variation of deviation from ideal molar volume in the diffusion zone of the couple is larger.

Figure 4a shows that the molar volume for Couple DC-1 varies almost parallelly with the variation shown by its ideal molar volume. Thus, in

Figure 4b, the overall variation in deviation from ideal molar volume varies by small amount (~1.4% points) over the diffusion zone. However, variation in deviation from ideality for the molar volumes of DC-2 and DC-3 in their respective diffusion regions is ~3.1 and 3 % points respectively. Correspondingly, the errors in fluxes are largest for DC-2 followed by DC-3 and the smallest for DC-1. It is interesting to note that the overall variation of molar volume is highest in DC-1 but the deviation from ideality is the lowest. On the other hand, DC-2 and DC-3 show much lesser overall variation in the molar volume but their deviation from ideality is larger. Thus, the deviation of the molar volume from ideal molar volume plays the most dominant effect in determining the local interdiffusion fluxes than the absolute variation in molar volume within the diffusion zone. This highlights the necessity of the newly derived equations for interdiffusion analysis of multicomponent diffusion couples exhibiting composition dependent partial molar volumes.

4. Discussion

The newly developed equations, Equations (29) and (34), are the exact expressions for interdiffusion flux of a component with respect to the number fixed frame and Equations (32) and (35) are those for the interdiffusion flux with respect to volume fixed frame as determined from experimental concentration profiles of a multicomponent diffusion couple with composition dependent partial molar volumes. By definition, Equation (29) gives the interdiffusion flux with respect to the local center of number of moles and Equation (32) gives that with respect to the local center of volume. Thus, both these equations are naturally independent of the reference coordinate (x0) used for the analysis. Moreover, since the variation in molar volume is accounted for, the equations are also applicable for the analysis of multicomponent multiphase diffusion couples.

The most significant outcome of the present work is that it proves that the popular SF equation for varying partial molar volumes is applicable only for binary interdiffusion analysis and its use, as it is, in the analysis of multicomponent systems leads to errors in the determination of fluxes. This is against the popular belief otherwise. In the Ni-Cr-Al couples studied here, it is observed that a mere 3-4% variation in deviation of molar volume from ideality leads to errors of -40 to 20% in the interdiffusion fluxes; see

Figure 4. A rough estimate, as described in Appendix C of

Supporting Data File, suggests that this would further propagate to more than 100% errors in interdiffusion coefficients evaluated from these fluxes if errors in all the fluxes add up. On the other hand, for small variations of molar volumes in the diffusion zone, the fluxes evaluated by the binary SF equation, Equation (38) are almost similar to those evaluated based on constant molar volume, Equation (41). A comparison in this regard for the three studied couples is presented in

Figure 2S in Appendix D of

Supporting Data File. Thus, the use of binary SF equation, Equation (38) to determination of fluxes in ternary and higher order systems is akin to the assumption of the constant molar volumes. This shows that the variation in partial molar volumes should not be ignored in the interdiffusion analysis of the multicomponent diffusion couples and that only the newly developed equations in this work must be used for the accurate analysis. This also calls for an urgent need for experimental determination of molar volumes as functions of compositions in various multicomponent systems; this point is also highlighted through the present author’s previous works [

17,

18].

With the increasing demand for accurate experimental data for use in advanced technology development such as artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML) and integrated computational materials engineering (ICME), considering composition-dependent molar volumes in multicomponent interdiffusion analysis is the need of the hour. However, there has been lack of such analysis so far, because of both the lack of experimental data on molar volumes in multicomponent systems and the lack of appropriate equations that can account for varying partial molar volumes while analyzing interdiffusion in multicomponent couples. Thus, the newly developed equations in the present work are expected to pave the way for detail experimental investigations of molar volumes of multicomponent systems as functions of compositions and to have a phenomenal impact on the experimental interdiffusion analysis of the multicomponent diffusion couples.

5. Conclusions

In the absence of the data on molar volumes as functions of compositions in the multicomponent systems, the analysis of experimental concentration profiles developed in a multicomponent diffusion couple for interdiffusion fluxes and coefficients has so far been carried out in the literature with the assumption of constant partial molar volumes. However, it has been, albeit wrongly, generally suggested, without any analytical work, that the binary SF equations Equation (38) can straight be used for ternary and higher order systems with composition dependent partial molar volumes to determine the interdiffusion fluxes in multicomponent diffusion couples. In the present work, new equations are derived for determination of interdiffusion fluxes from experimental concentration profiles of multicomponent diffusion couples with composition dependent molar volumes. Application of the newly developed equations to diffusion couples in FCC Ni-Cr-Al system shows that a mere 3% variation in deviation from ideality of the molar volume in the diffusion zone may lead to about -40% errors in fluxes if assumption of constant molar volume is employed or if the SF equation proposed for binary diffusion is used. This may further translate to more than 100% errors in the interdiffusion coefficients determined from such fluxes. This emphasizes the need for development of databases for molar volumes in multicomponent systems and also, the necessity of the use of the newly developed equations in interdiffusion analysis of the multicomponent diffusion couples with varying partial molar volumes. The newly developed equations are independent of the reference coordinates used i.e., they do not need the location of the initial contact plane and, they are also applicable for the analysis of multicomponent multiphase diffusion couples.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org.

Acknowledgement

This work is financially supported by internal grants of IIT Kanpur.

References

- Darken, L.S. Diffusion, Mobility and Their Interrelation through Free Energy in Binary Metallic Systems. Transactions of AIME 1948, 175, 184–201. [Google Scholar]

- Darken, L.S. Formal Basis of Diffusion Theory, in Atom Movements; ASM: Cleveland, Ohio, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkaldy, J.S.; Lane, J.E.; Meson, G.R. Diffusion in Multicomponent Metallic Systems VII. Solutions of the Multicomponent Diffusion Equations with Variable Coefficients. Canadian Journal of Physics 1963, 41, 2174–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkaldy, J.S.; Lane, J.E. Diffusion in Multicomponent Metallic Systems IX. Intrinsic Diffusion Behavior and Kirkendall Effect in Ternary Substitutional Solutions. Canadian Journal of Physics 1966, 44, 2059–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, P.T.; Dayananda, M.A.; Grace, R.E. Diffusion in Ternary Ag-Zn-Cd Solid Solutions. Metallurgical Transactions 1972, 3, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, T.D.; Dayananda, M.A. Diffusion in β2 Fe-Ni-Al Alloys. Metallurgical Transactions A 1976, 7A, 1035–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayananda, M.A.; Kim, C.W. Zero Flux Planes and Flux Reversals in Cu-Ni-Zn Diffusion Couples. Metallurgical Transactions A 1979, 10, 1333–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, J.A.; Heckel, R.W. Interdiffusion in Ni-Rich Ni-Cr-Al Alloys at 1100 and 1200 °C: Part I. Diffusion Paths and Microstructures. Metallurgical Transactions A 1987, 18, 2061–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, J.A.; Heckel, R.W. Interdiffusion in Ni-Rich Ni-Cr-Al Alloys at 1100 and 1200 °C: Part II. Diffusion Coefficients and Predicted Concentration Profiles. Metallurgical Transactions A 1987, 18, 2075–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchet, R.; Mevrel, R. A Numerical Inverse Method for Calculating the Interdiffusion Coefficients Along a Diffusion Path in Ternary Systems. Acta Materialia 2002, 50, 4887–4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunaratne, M.S.A.; Reed, R.C. Interdiffusion of the Platinum Group Metals in Nickel at Elevated Temperatures. Acta Materialia 2003, 51, 2905–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram-Mohan, L.R.; Dayananda, M.A. A Transfer Matrix Method for the Calculation of Concentrations and Fluxes in Multicomponent Diffusion Couples. Acta Materialia 2006, 54, 2325–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayananda, M.A. A Direct Derivation of Fick’s Law from Continuity Equation for Interdiffusion in Multicomponent Systems. Scripta Materialia 2022, 210, 114430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Tripathi, A.; Venkateswaran, T.; Kulkarni, K.N. First Report on Entire Sets of Experimentally Determined Interdiffusion Coefficients in Quaternary and Quinary High-Entropy Alloys. Journal of Materials Research 2020, 35, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Kulkarni, K.N. Square Root Diffusivity Analysis of Body-Diagonal Diffusion Couples in FeNiCoCr quaternary and FeNiCoCrMn quinary systems. Journal of Phase Equilibria and Diffusion 2022, 43, 903–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, G.P.S.; Kulkarni, K.N. Investigations of Ternary Interdiffusion in β-(BCC) Phase Field of Ti-Al-Mo System. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 2021, 52, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, K.N. Derivation of expressions for interdiffusion and intrinsic diffusion flux in presence of chemical potential gradient in a multicomponent system with composition dependent molar volume. Oxford Open Materials Science 2023, 3, itad018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, K.N. Velocity of Volume Fixed Frame and Its Application in Simulating Concentration Profiles in Multicomponent Diffusion. Journal of Phase Equilibria and Diffusion 2024, 45, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boltzmann, L. Zur Integration der Diffusionsgleichung bei variable Diffusionscoefficienten. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry 1894, 53, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matano, C. On the Relation between Diffusion-Coefficients and Concentrations of Solid Metals (The Nickel-Copper System). Japanese Journal of Physics 1935, 8, 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, F.; Freise, V. Diffusion in binären Gemischen mit Volumenänderung. 1962; 66, 353–362. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, C. The Evaluation of Data Obtained with Diffusion Couples for Binary Single-Phase and Multiphase Systems. Acta Metallurgica 1969, 17, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Broeder, F.J.A. A General Simplification and Improvement of the Matano-Boltzmann Method in the Determination of the Interdiffusion Coefficients in Binary Systems. Scripta Materialia 1969, 3, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balluffi, R. On the Determination of Diffusion Coefficients in Chemical Diffusion. Acta Metallurgica 1960, 8, 871–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, A.G.; DeHoff, R.T.; Smith, C. Calculation of Interdiffusion Coefficients Considering Variations in Atomic Volume. ASM Transactions Quarterly 1968, 61, 314–320. [Google Scholar]

- Danielewski, M.; Leszczynski, H. Generalization of Matano’s Method: Interdiffusion in Solutions with Volume Change. International Journal of Mathematical Analysis 2015, 9, 1463–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Kulkarni, K.N. Effect of Varying Molar Volume on Interdiffusion Analysis in a Binary System. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 2021, 52, 3489–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, G.W.; Whittle, D.P. Interdiffusion in Ternary Co-Cr-Al Alloys. Metal Science 1980, 14, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, J.R. Cross Terms in the Thermodynamic Diffusion Equations for Multicomponent Alloys. Metallurgical Transactions 1970, 1, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A. Effect of Molar Volume of Diffusing Elements and Cross Terms of Onsager Formalism (Vacancy Wind Effect) on Estimated Diffusion Coefficients in Ternary and Multicomponent Solid Solutions. Materialia 2025, 40, 102400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayananda, M.A. An analysis of Concentration Profiles for Fluxes, Diffusion Depths, and Zero Flux Planes in Multicomponent Systems. Metallurgical Transactions A 1983, 14, 1851–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayananda, M.A.; Behnke, D.A. Effective Interdiffusion Coefficients and Penetration Depths. Scripta Materialia 1991, 25, 2187–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayananda, M.A. Average Effective Interdiffusion Coefficients and the Matano Plane Composition. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 1996, 27, 2504–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayananda, M.A. Determination of Eigenvalues, Eignevectors, and Interdiffusion Coefficients in Ternary Diffusion From Diffusional Constraints at the Matano Plane. Acta Materialia 2017, 129, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, J.G.; Baldwin, R.L.; Dunlop, P.J.; Gosting, L.J.; Kegeles, G. Flow Equations and Frames of Reference for Isothermal Diffusion in Liquids. Journal of Chemical Physics 1960, 33, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, J. Reference Frames and Diffusion Coefficients. American Journal of Science 1975, 275, 954–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philibert, J. Atom movements- Diffusion and mass transport in solids, Les Editions de Physique, France. 1991; 233–241. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni, K.N.; Samantaray, B.; Nayak, S.K. Ternary Interdiffusion Coefficients in BCC Ti-Al Based Alloys and Their Application in Simulations of Homogenization and Finite Diffusion Couples. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 2024, 55, 4882–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.; Floyd, R.W. The Constitution of Nickel-Rich Alloys in the Nickel-Chromium-Aluminum System. Journal of the Institute of Metals 1953, 81, 451–464. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, W.B. A Handbook of Lattice Spacings and Structures of Metals and Alloys, International Series of Monographs on Metal Physics and Physical Metallurgy, Volume 4; Raynor, G.V., Ed.; Pergamon Press, 1964; pp. 324–326. [Google Scholar]

- Day, K.M.; Ram-Mohan, L.R.; Dayananda, M.A. Determination and Assessment of Interdiffusion Coefficients from Individual Diffusion Couples. Journal of Phase Equilibria and Diffusion 2005, 26, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).