Submitted:

13 May 2025

Posted:

14 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

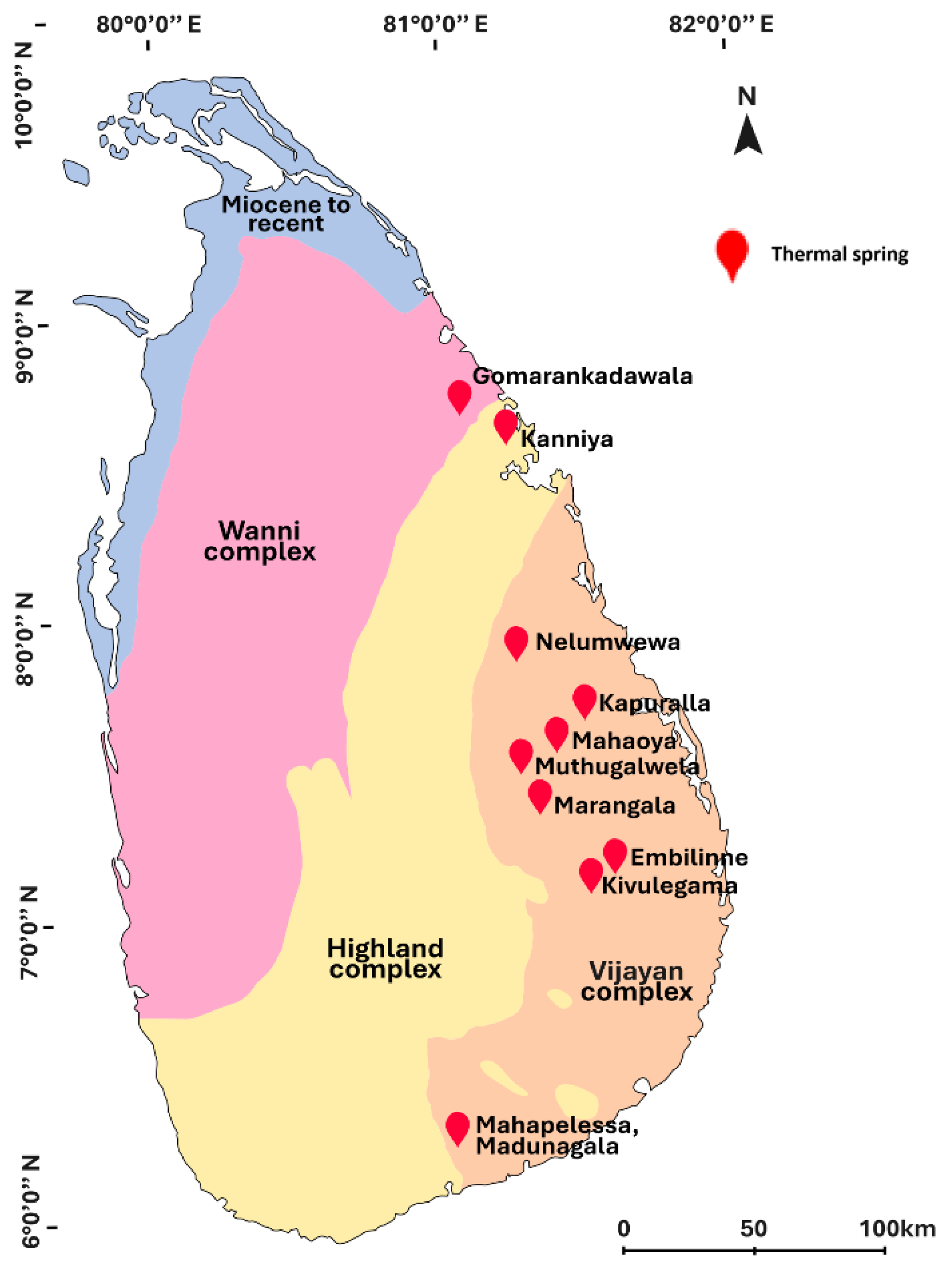

2.1. Water Sample Collection

2.2. Isolation of Thermophilic Bacteria from Water Samples

2.3. Catalase Test

2.4. Screening of Thermophilic Bacterial Isolates for Extracellular Amylase Production

2.5. Screening of Thermophilic Bacterial Isolates for Extracellular Protease Production

2.6. Molecular Characterization of Isolated Thermophilic Bacteria by 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.7. Determination of the Optimum Growth Temperature for the NW2 Isolate

2.8. Isolation of Crude Extracellular Amylase Enzyme from the NW2 Isolate

2.9. Extracellular Amylase Activity Analysis by DNSA Assay

2.10. Determination of the Optimum Temperature for the Extracellular Amylase Activity

2.11. Determination of Optimum pH for the Extracellular Amylase Activity

2.12. Hydrolysis of Raw Cassava Starch by Crude Extracellular Amylase

3. Results

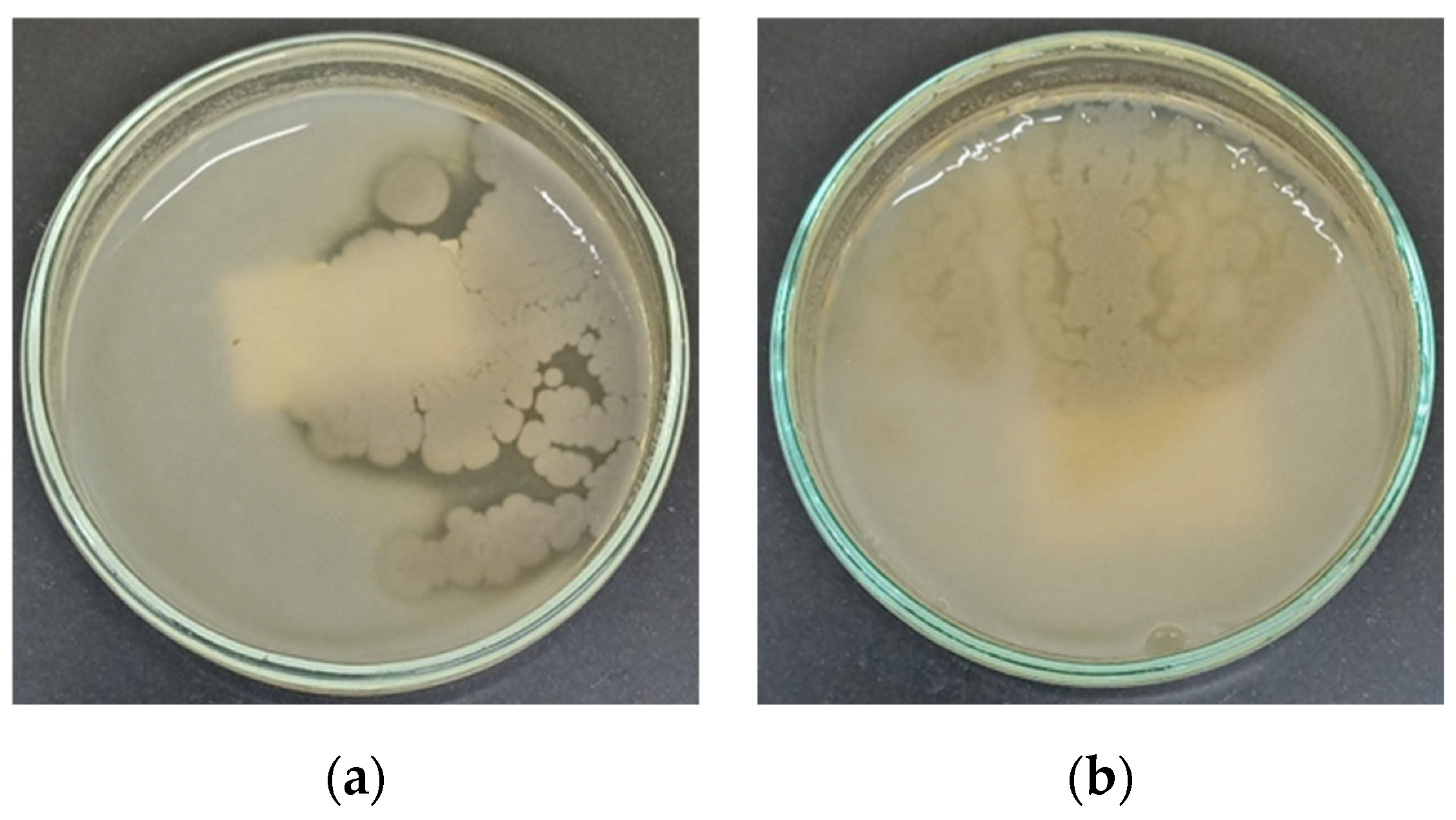

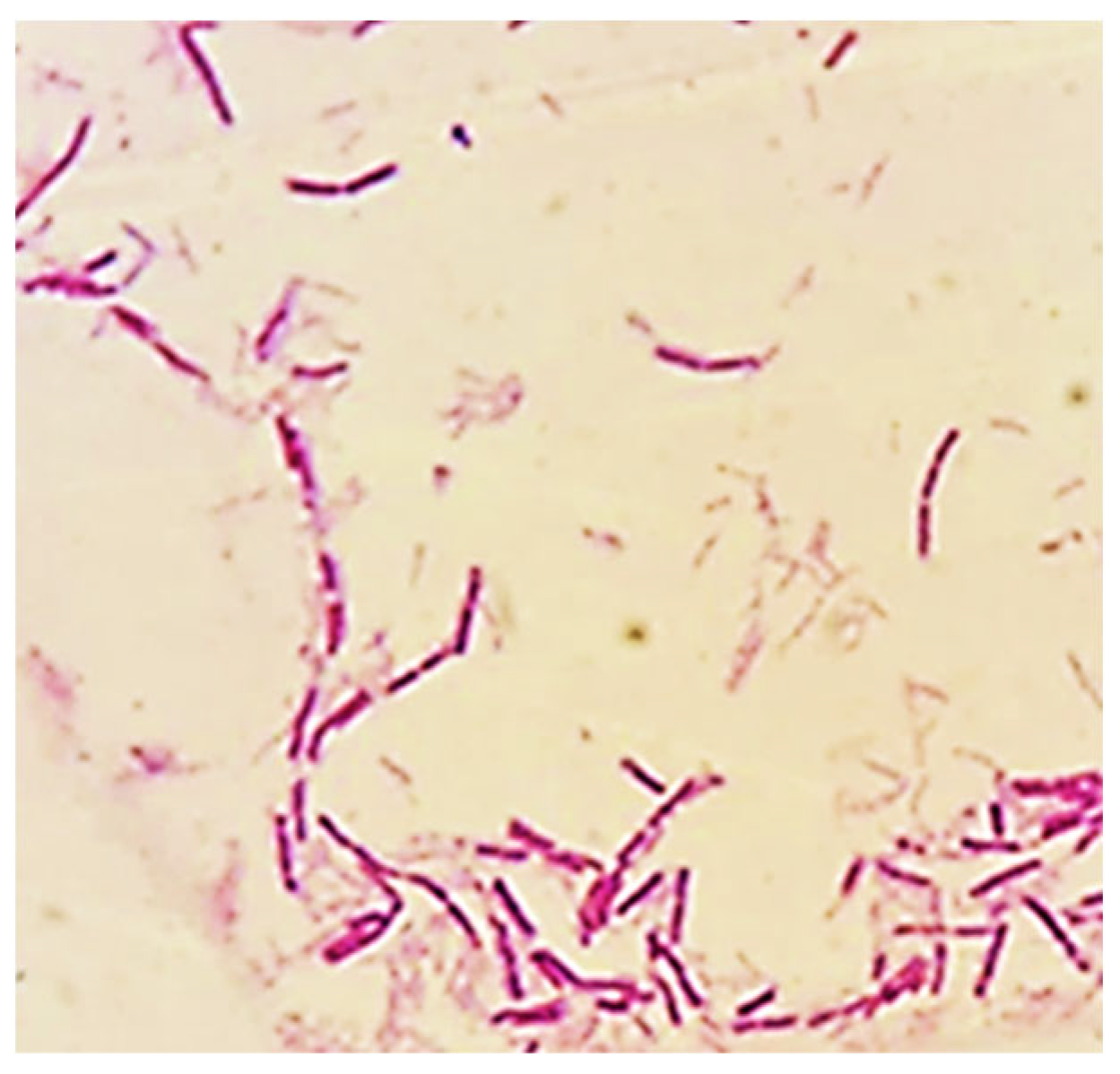

3.1. Isolation, Morphological and Biochemical Characterization of Thermophilic Bacterial Strains

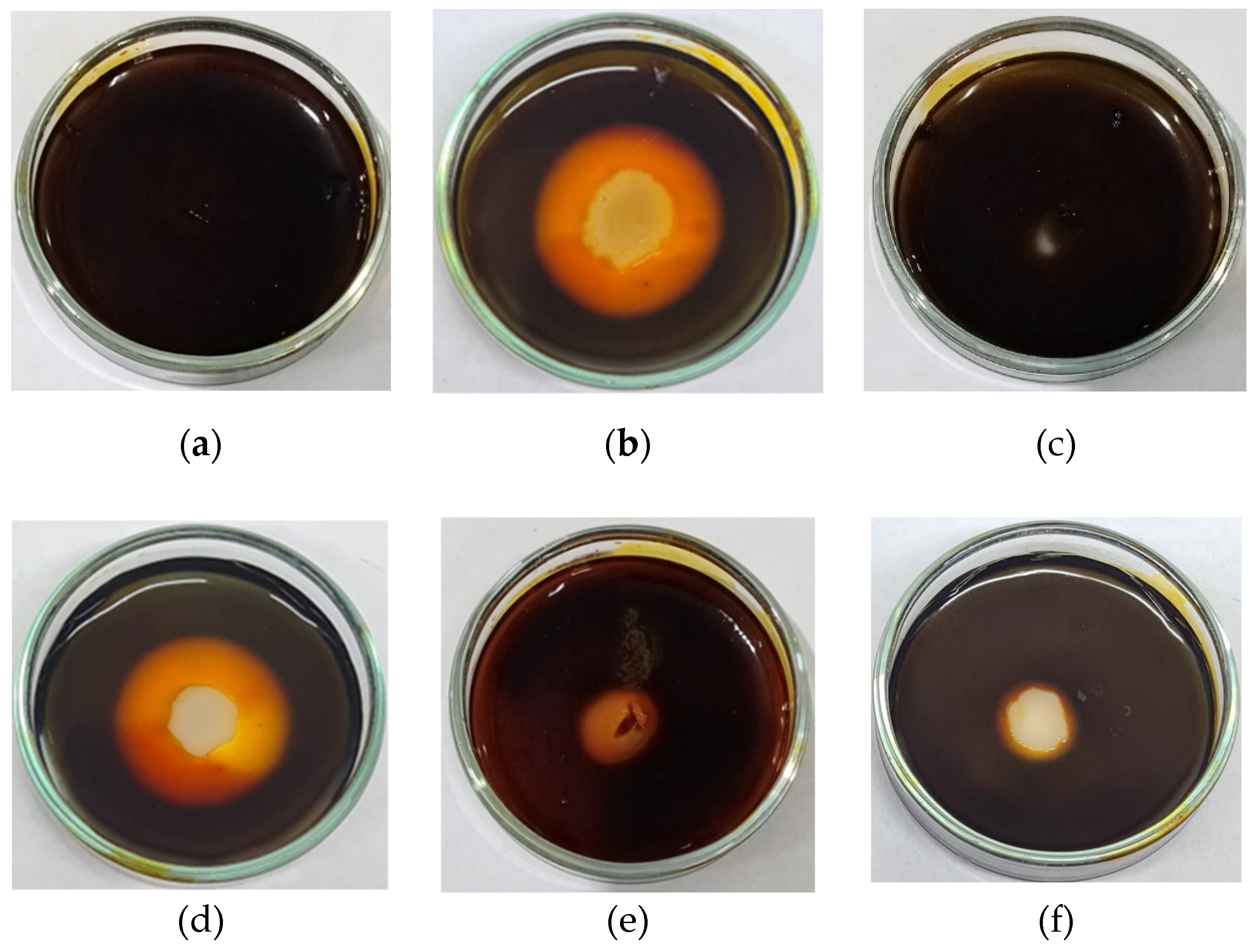

3.2. Identification of Thermophilic Bacterial Isolates That Produce Extracellular Amylase and Protease

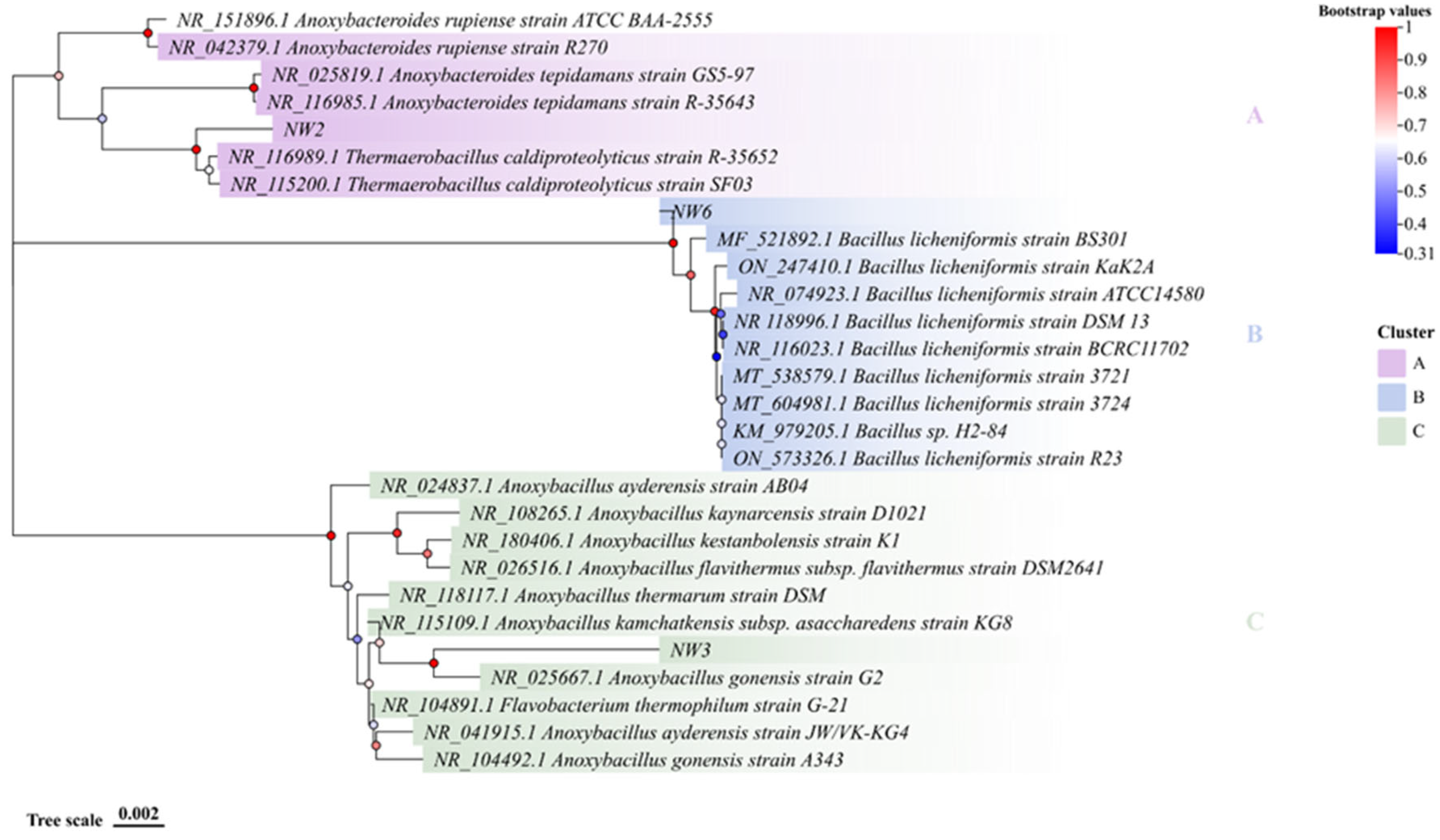

3.3. Molecular Characterization of Thermophilic Bacterial Isolates

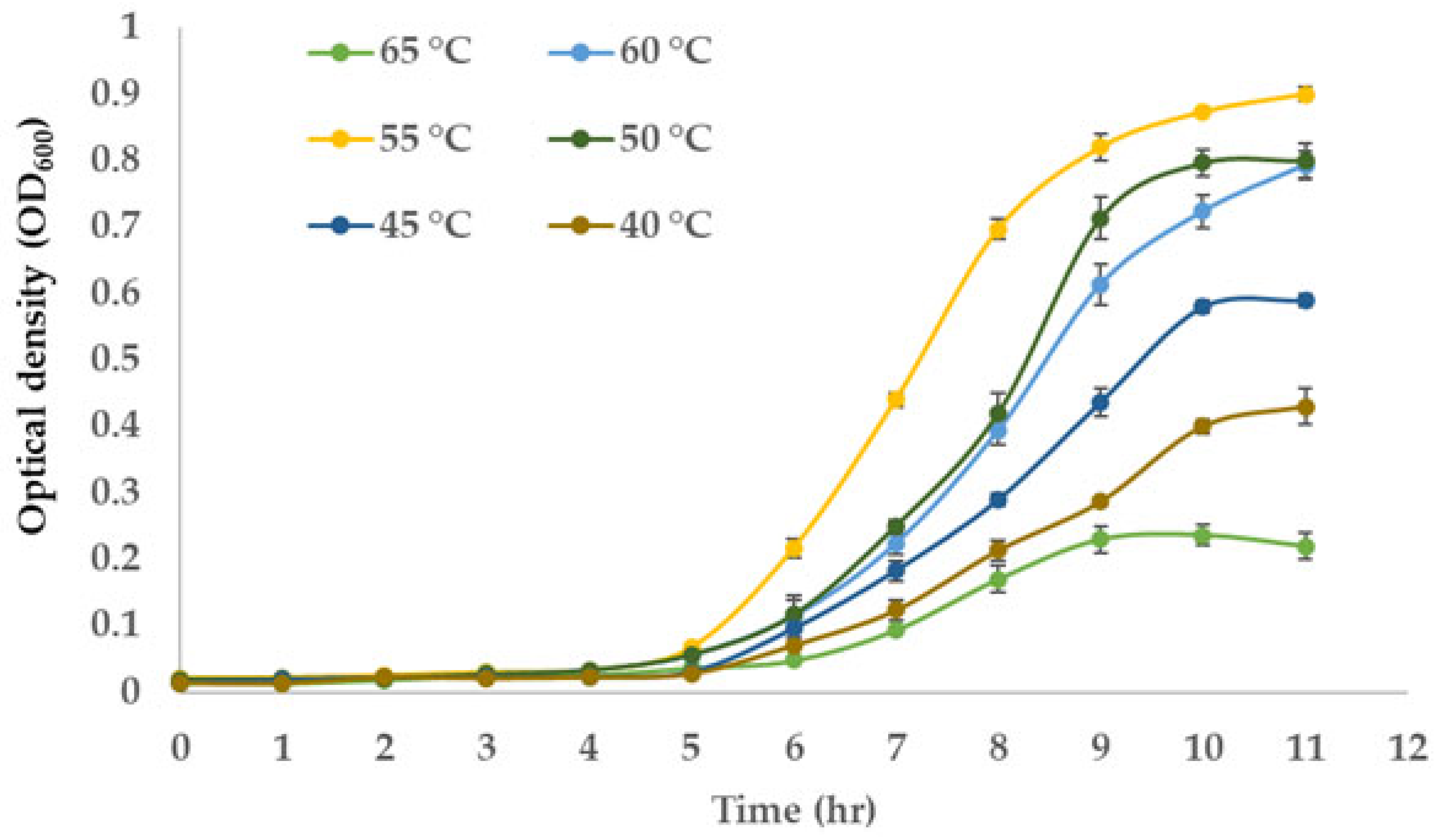

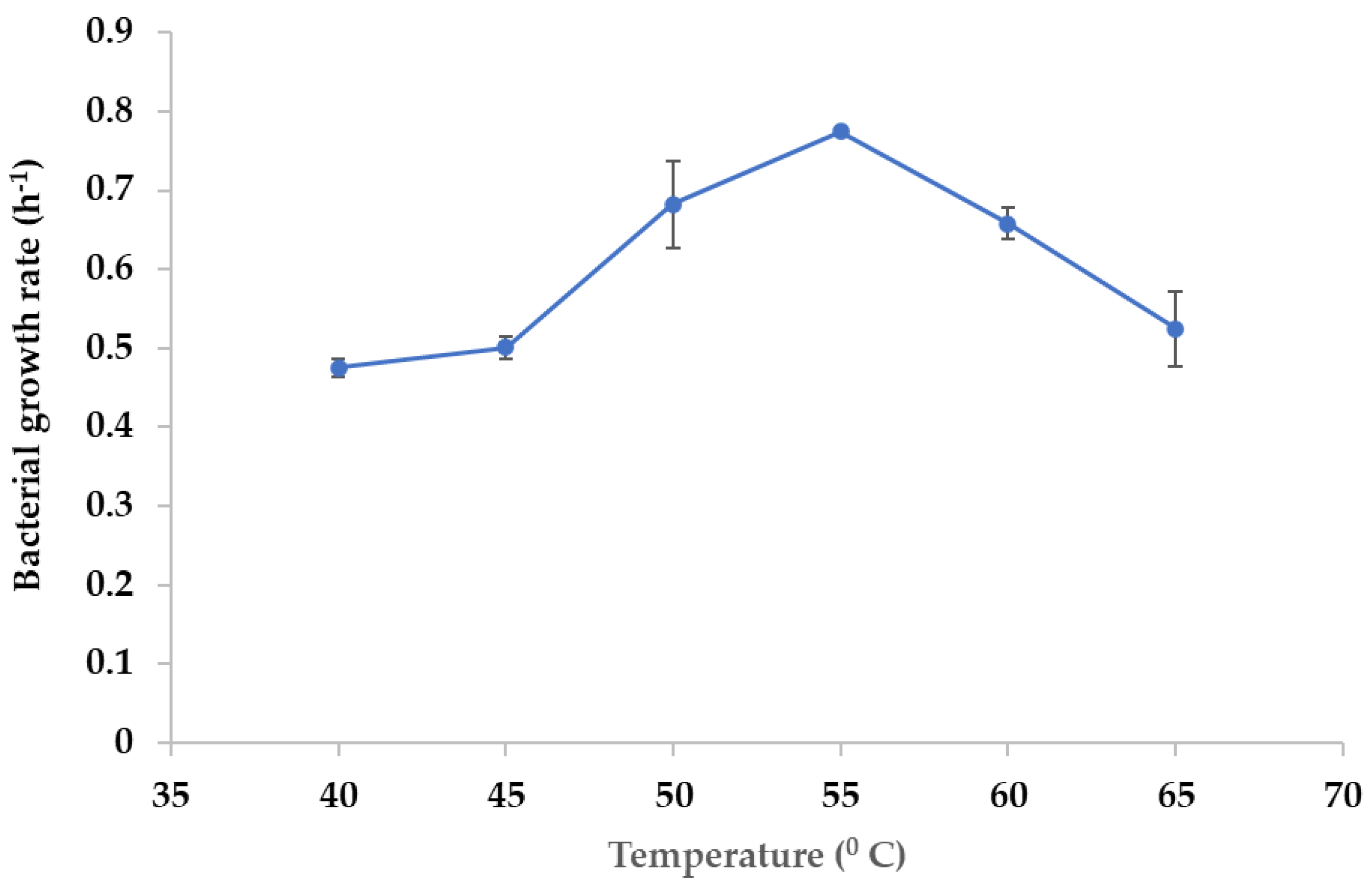

3.4. Optimum Growth Temperature of the NW2 Isolate

3.5. Characterization of Crude Extracellular Amylase Produced by NW2 Isolate

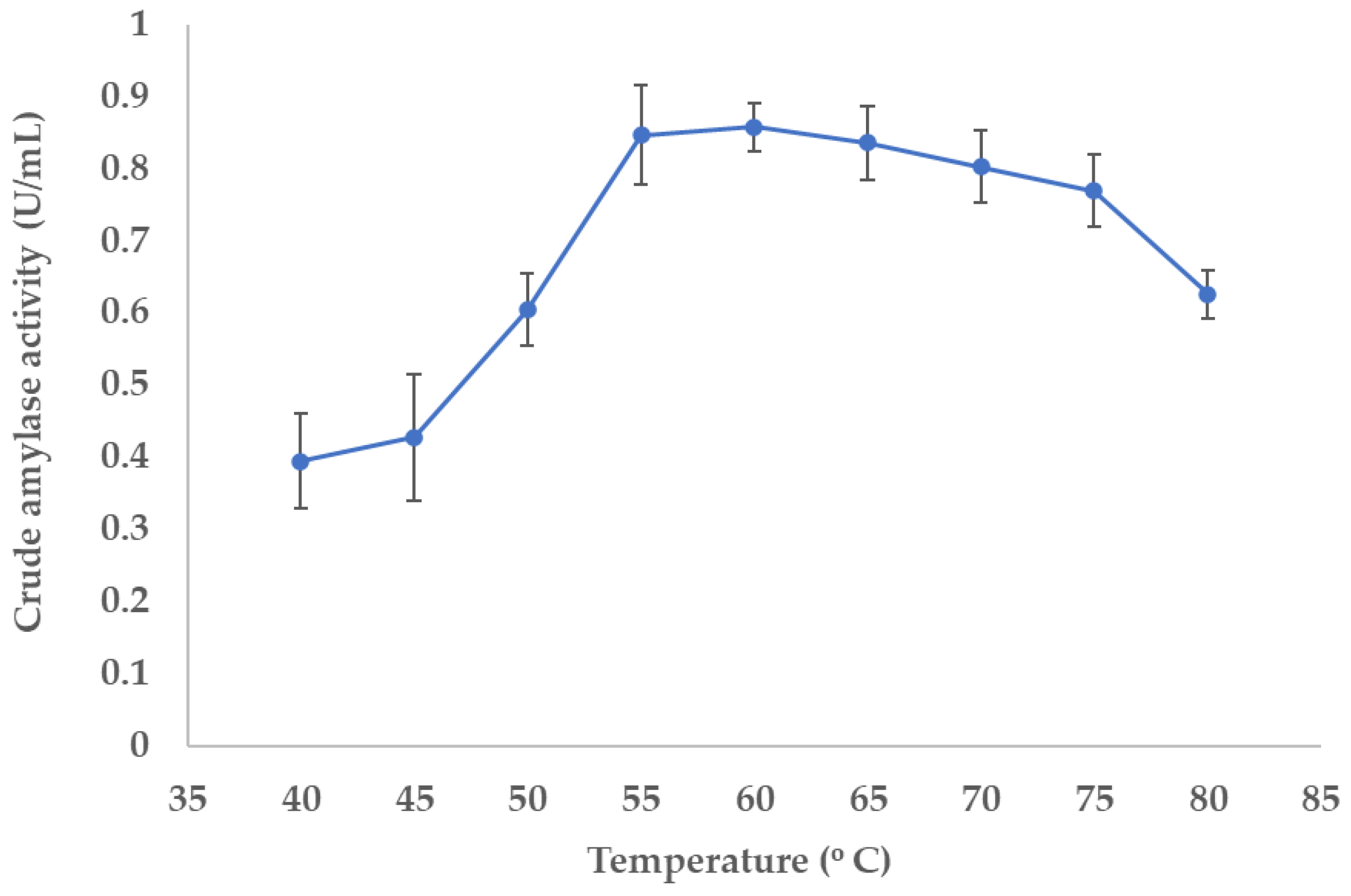

3.5.1. Determination of Optimal Temperature for the Enzyme Activity

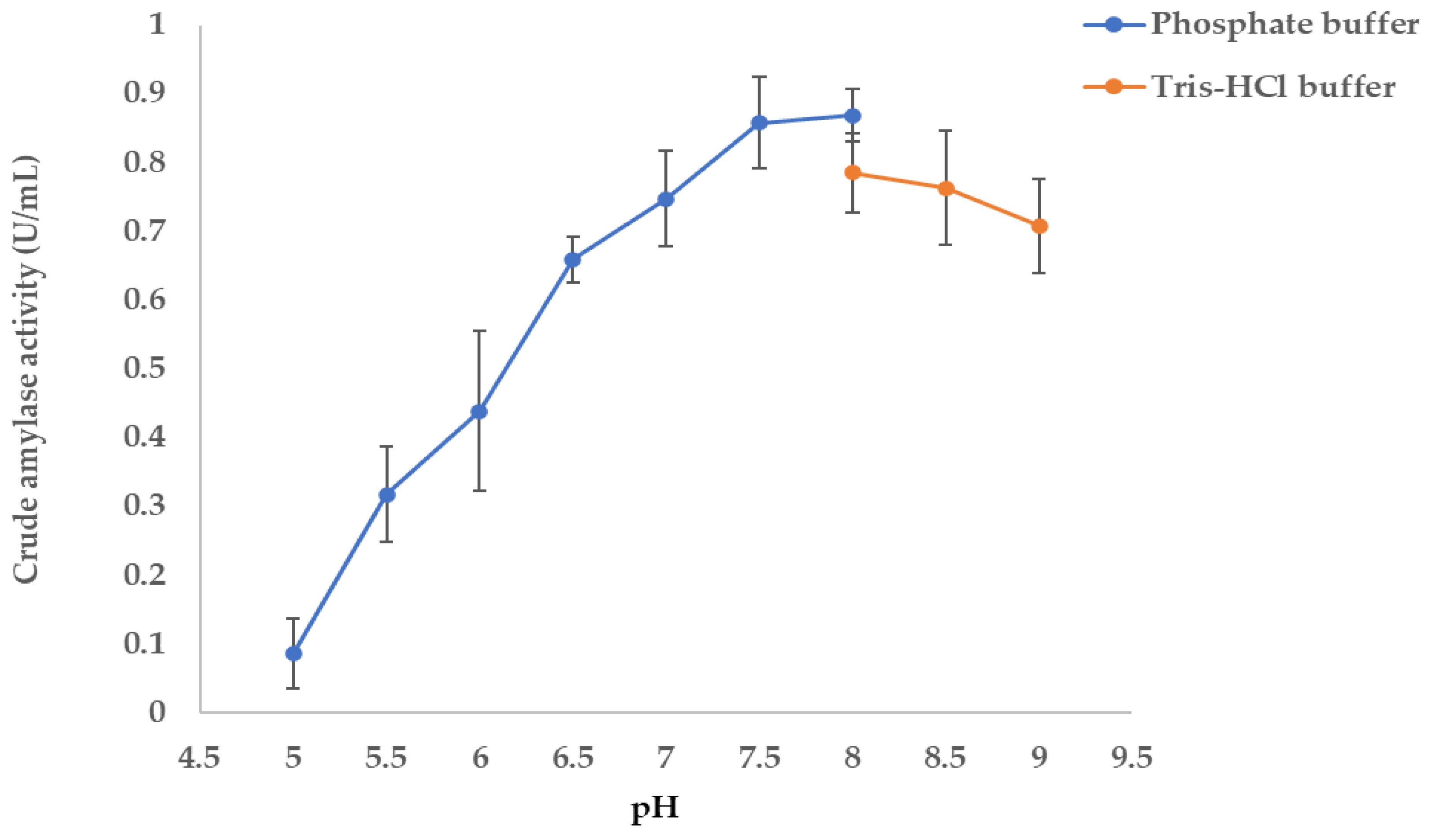

3.5.2. Determination of Optimal pH Enzyme Activity

3.6. Extracellular Crude Amylase Activity of NW2 Isolate Under Optimum Temperature and pH

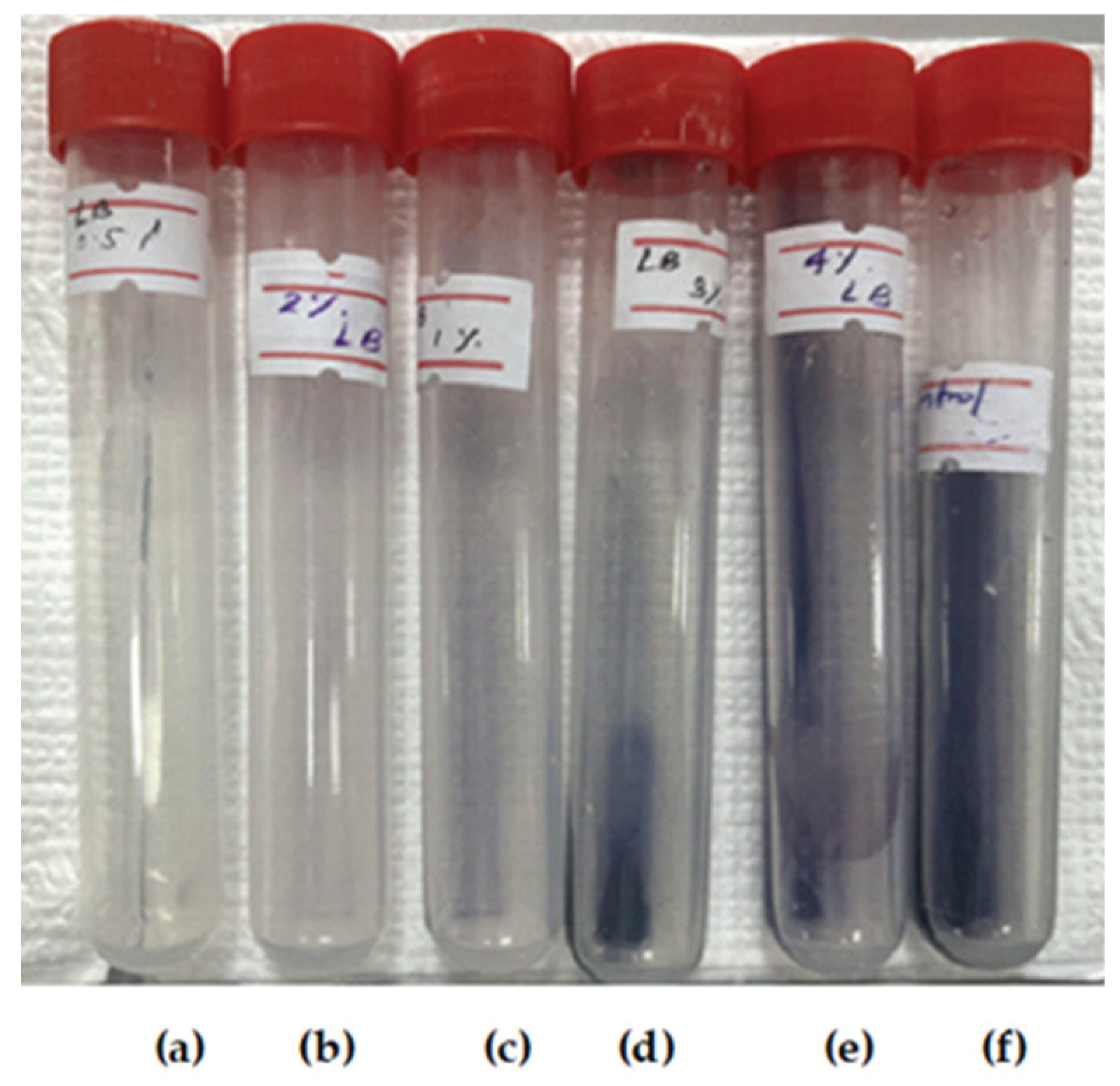

3.7. Hydrolysis of Raw Cassava Starch by NW2 Crude Extracellular Amylase

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NB | Nutrient broth |

| DNSA | 3,5-Dinitrosalicylic acid |

References

- Raddadi, N.; Cherif, A.; Daffonchio, D.; Neifar, M.; Fava, F. Biotechnological Applications of Extremophiles, Extremozymes and Extremolytes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2015, 99, 7907–7913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, M.Á.; Blamey, J.M. Biotechnological Applications of Archaeal Enzymes from Extreme Environments. Biological Research 2018, 51, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzban, G.; Tesei, D. The Extremophiles: Adaptation Mechanisms and Biotechnological Applications. Biology 2025, 14, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elleuche, S.; Schröder, C.; Sahm, K.; Antranikian, G. Extremozymes-Biocatalysts with Unique Properties from Extremophilic Microorganisms. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2014, 29, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavicchioli, R.; Siddiqui, K.S.; Andrews, D.; Sowers, K.R. Low-Temperature Extremophiles and Their Applications. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2002, 13, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashaolu, T.J.; Malik, T.; Soni, R.; Prieto, M.A.; Jafari, S.M. Extremophilic Microorganisms as a Source of Emerging Enzymes for the Food Industry: A Review. Food Sci Nutr 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Batayneh, K.M.; Jacob, J.H.; Hussein, E. Isolation and Molecular Identification of New Thermophilic Bacterial Strains of Geobacillus Pallidus and Anoxybacillus Flavithermus. 2011; Vol. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Cen, Z.; Zhao, J. The Survival Mechanisms of Thermophiles at High Temperatures: An Angle of Omics. Physiology 2015, 30, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikani, B.A.; Singh, S.P. Amylases from Thermophilic Bacteria: Structure and Function Relationship. Crit Rev Biotechnol 2022, 42, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbab, S.; Ullah, H.; Khan, M.I.U.; Khattak, M.N.K.; Zhang, J.; Li, K.; Hassan, I.U. Diversity and Distribution of Thermophilic Microorganisms and Their Applications in Biotechnology. J Basic Microbiol 2022, 62, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Abdullah, M.; Yasin, M.T.; Amanat, K.; Sultan, M.; Rahim, A.; Sarwar, F. Recent Trends in Production and Potential Applications of Microbial Amylases: A Comprehensive Review. Protein Expr Purif 2025, 227, 106640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, O.; Jaiswal, N. α-Amylase: An Ideal Representative of Thermostable Enzymes. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2010, 160, 2401–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavić, M.Š.; Kojić, M.; Margetić, A.; Stanisavljević, N.; Gardijan, L.; Božić, N.; Vujčić, Z. Highly Stable and Versatile α-Amylase from Anoxybacillus Vranjensis ST4 Suitable for Various Applications. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 249, 126055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikani, B.A.; Singh, S.P. The Stability and Thermodynamic Parameters of a Very Thermostable and Calcium-Independent α-Amylase from a Newly Isolated Bacterium, Anoxybacillus Beppuensis TSSC-1. Process Biochemistry 2012, 47, 1791–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agüloǧlu Fincan, S.; Enez, B.; Özdemir, S.; Matpan Bekler, F. Purification and Characterization of Thermostable α-Amylase from Thermophilic Anoxybacillus Flavithermus. Carbohydr Polym 2014, 102, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammar, Y.B.; Matsubara, T.; Ito, K.; Iizuka, M.; Limpaseni, T.; Pongsawasdi, P.; Minamiura, N. New Action Pattern of a Maltose-Forming α-Amylase from Streptomyces Sp. and Its Possible Application in Bakery. BMB Rep 2002, 35, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.H.; Liu, W.H. Purification and Properties of a Maltotriose-Producing α-Amylase from Thermobifida Fusca. Enzyme Microb Technol 2004, 35, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burhan, A.; Nisa, U.; Gökhan, C.; Ömer, C.; Ashabil, A.; Osman, G. Enzymatic Properties of a Novel Thermostable, Thermophilic, Alkaline and Chelator Resistant Amylase from an Alkaliphilic Bacillus Sp. Isolate ANT-6. Process Biochemistry 2003, 38, 1397–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Khan, M.S.; Khan, S.S.; Ahmad, W.; Zheng, L.; Shah, S.U.A.; Ullah, M.; Iqbal, A. Identification and Characterization of Thermophilic Amylase Producing Bacterial Isolates from the Brick Kiln Soil. Saudi J Biol Sci 2021, 28, 970–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Salinas, A.; Rodríguez-Delgado, M.; Gómez-Treviño, J.; López-Chuken, U.; Olvera-Carranza, C.; Blanco-Gámez, E.A. Novel Thermotolerant Amylase from Bacillus Licheniformis Strain Lb04: Purification, Characterization and Agar-Agarose. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deljou, A.; Arezi, I. Production of Thermostable Extracellular α-Amylase by a Moderate Thermophilic Bacillus Licheniformis-AZ2 Isolated from Qinarje Hot Spring (Ardebil Prov. of Iran). Period Biol 2016, 118, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acer, Ö.; Pirinççioʇlu, H.; Matpan Bekler, F.; Gül-Güven, R.; Güven, K. Anoxybacillus Sp. AH1, an α-Amylase-Producing Thermophilic Bacterium Isolated from Dargeçit Hot Spring. Biologia (Poland) 2015, 70, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, S.; Shah, A.H.; Fariq, A.; Jannat, S.; Rasheed, S.; Yasmin, A. Optimization of Amylase Production Using Response Surface Methodology from Newly Isolated Thermophilic Bacteria. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harthy, O.D.; Hozzein, W.N.; Abdelkader, H.S.; Alharbi, S.A.A. Thermostable Amylase from Cytobacillus Firmus: Characterization, Optimization, and Implications in Starch Hydrolysis. Egypt J Microbiol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarasinghe, S.N.; Wanigatunge, R.P.; Magana-Arachchi, D.N. Bacterial Diversity in a Sri Lankan Geothermal Spring Assessed by Culture-Dependent and Culture-Independent Approaches. Curr Microbiol 2021, 78, 3439–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patabendigedara, S.; Kumara, S.M.P.G.S.; Dharmagunawardhane, H.A. GEOSTRUCTURAL MODEL FOR THE NELUMWEWA THERMAL SPRING; NORTH CENTRAL PROVINCE, SRI LANKA A GEOSTRUCTURAL MODEL FOR THE NELUMWEWA THERMAL SPRING: NORTH CENTRAL PROVINCE, SRI LANKA, 2014; Vol. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Reiner, K. Catalase Test Protocol. - References - Scientific Research Publishing. 2012. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1367750 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Hols, P.; Ferain, T.; Garmyn, D.; Bernard, N.; Delcour, J. Use of Homologous Expression-Secretion Signals and Vector-Free Stable Chromosomal Integration in Engineering of Lactobacillus Plantarum for Alpha-Amylase and Levanase Expression. Appl Environ Microbiol 1994, 60, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, B.G. Building Phylogenetic Trees from Molecular Data with MEGA. Mol Biol Evol 2013, 30, 1229–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Chen, Y.; Cai, G.; Cai, R.; Hu, Z.; Wang, H. Tree Visualization by One Table (TvBOT): A Web Application for Visualizing, Modifying and Annotating Phylogenetic Trees. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, W587–W592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernfeld, P. [17] Amylases, α and β. Methods Enzymol 1955, 1, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soy, S.; Nigam, V.K.; Sharma, S.R. Enhanced Production and Biochemical Characterization of a Thermostable Amylase from Thermophilic Bacterium Geobacillus Icigianus BITSNS038. Journal of Taibah University for Science 2021, 15, 730–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.N. Biodiversity and Bioprospecting of Extremophilic Microbiomes for Agro-Environmental Sustainability. J Appl Biol Biotechnol 2021, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, I.; Bello, S.; Gupta, R.S. Phylogenomic and Molecular Marker Based Studies to Clarify the Evolutionary Relationships amongst Anoxybacillus Species and Demarcation of the Family Anoxybacillaceae and Some of Its Constituent Genera. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2024, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coorevits, A.; Dinsdale, A.E.; Halket, G.; Lebbe, L.; de Vos, P.; van Landschoot, A.; Logan, N.A. Taxonomic Revision of the Genus Geobacillus: Emendation of Geobacillus, G. Stearothermophilus, G. Jurassicus, G. Toebii, G. Thermodenitrificans and G. Thermoglucosidans (Nom. Corrig., Formerly ’Thermoglucosidasius’); Transfer of Bacillus Thermantarcticus to the Genus as G. Thermantarcticus Comb. Nov.; Proposal of Caldibacillus Debilis Gen. Nov., Comb. Nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2012, 62, 1470–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Sun, M.L.; Zhang, X.; Song, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.L. Characterization and Diversity Analysis of the Extracellular Proteases of Thermophilic Anoxybacillus Caldiproteolyticus 1A02591 From Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vent Sediment. Front Microbiol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.G.; Stabnikova, O.; Tay, J.H.; Wang, J.Y.; Tay, S.T.L. Thermoactive Extracellular Proteases of Geobacillus Caldoproteolyticus, Sp. Nov., from Sewage Sludge. Extremophiles 2004, 8, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simair, A.A.; Khushk, I.; Qureshi, A.S.; Bhutto, M.A.; Chaudhry, H.A.; Ansari, K.A.; Lu, C. Amylase Production from Thermophilic Bacillus Sp. BCC 021-50 Isolated from a Marine Environment. Fermentation 2017, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmidet, N.; El Hadj Ali, N.; Zouari-Fakhfakh, N.; Haddar, A.; Nasri, M.; Sellemi-Kamoun, A. Chicken Feathers: A Complex Substrate for the Co-Production of α-Amylase and Proteases by B. Licheniformis NH1. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2010, 37, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmidet, N.; Bayoudh, A.; Berrin, J.G.; Kanoun, S.; Juge, N.; Nasri, M. Purification and Biochemical Characterization of a Novel α-Amylase from Bacillus Licheniformis NH1. Cloning, Nucleotide Sequence and Expression of AmyN Gene in Escherichia Coli. Process Biochemistry 2008, 43, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msarah, M.J.; Ibrahim, I.; Hamid, A.A.; Aqma, W.S. Optimisation and Production of Alpha Amylase from Thermophilic Bacillus Spp. and Its Application in Food Waste Biodegradation. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konsoula, Z.; Liakopoulou-Kyriakides, M. Co-Production of α-Amylase and β-Galactosidase by Bacillus Subtilis in Complex Organic Substrates. Bioresour Technol 2007, 98, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, I.; Gomes, J.; Steiner, W. Highly Thermostable Amylase and Pullulanase of the Extreme Thermophilic Eubacterium Rhodothermus Marinus: Production and Partial Characterization. Bioresour Technol 2003, 90, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, K.; Bader, J.; Brokamp, C.; Popović, M.K.; Bajpai, R.; Berovič, M. Dual Feeding Strategy for the Production of α-Amylase by Bacillus Caldolyticus Using Complex Media. N Biotechnol 2009, 26, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uma Maheswar Rao, J.L.; Satyanarayana, T. Improving Production of Hyperthermostable and High Maltose-Forming α-Amylase by an Extreme Thermophile Geobacillus Thermoleovorans Using Response Surface Methodology and Its Applications. Bioresour Technol 2007, 98, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CALISKAN OZDEMIR, S.; COLERI CIHAN, A.; KILIC, T.; COKMUS, C. OPTIMIZATION OF THERMOSTABLE ALPHA-AMYLASE PRODUCTION FROM GEOBACILLUS SP. D413. Journal of microbiology, biotechnology and food sciences 2016, 6, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, W.J.; Ryu, J.; Yerefu, Y.; Tesfaw, A. Amylase Production by the New Strains of Kocuria Rosea and Micrococcus Endophyticus Isolated from Soil in the Guassa Community Conservation Area. Fermentation 2025, 11, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, S.; Altıntas, R.; Aygun, E.; Goren, G.; Sisecioglu, M. Purification of α-Amylase from Thermophilic Bacillus Licheniformis SO5 by Using a Novel Method, Alternating Current Magnetic-Field Assisted Three-Phase Partitioning: Molecular Docking and Bread Quality Improvement. Food Chem 2025, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoudnia, F. Comparison of the Synthesis of the Alpha-Amylase Enzyme by the Native Strain Bacillus Licheniformis in Immobilized and Immersed Cells. Iran J Microbiol 2024, 16, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthar, S.; Joshi, D.; Patel, H.; Patel, D.; Kikani, B.A. Optimization and Purification of a Novel Calcium-Independent Thermostable, α-Amylase Produced by Bacillus Licheniformis UDS-5. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2024, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divakaran, D.; Chandran, A.; Pratap Chandran, R. Comparative Study on Production of A-Amylase from Bacillus Licheniformis Strains. Braz J Microbiol 2011, 42, 1397–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roble, N.D.; Ogbonna, J.; Tanaka, H. Simultaneous Amylase Production, Raw Cassava Starch Hydrolysis and Ethanol Production by Immobilized Aspergillus Awamori and Saccharomyces Cerevisiae in a Novel Alternating Liquid Phase–Air Phase System. Process Biochemistry 2020, 95, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bacterial Isolate | NW1 | NW2 | NW3 | NW4 | NW6 | MD2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colony morphology | ||||||

| Shape | Circular | Circular | Circular | Circular | Irregular | Irregular |

| Margin | Entire | Entire | Entire | Entire | Undulate | Undulate |

| Elevation | Convex | Convex | Convex | Convex | Flat | Flat |

| Surface | Smooth | Smooth | Smooth | Smooth | Wrinkled | Wrinkled |

| Color | Off- white | Creamy white | Creamy white | Creamy white | Off- white |

Off- white |

| Cell shape | Rod | Rod | Rod | Rod | Rod | Rod |

| Catalase activity | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Extracellular enzymes activity | ||||||

| Amylase (Average diameter of clear zone in mm) | 0 | 25 | 0 | 25 | 5 | 5 |

| Protease | - | + | - | + | - | - |

| Isolates | Accession number 1 | Closest relative bacterial species 2 | Accession number 3 | Identity 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NW2/NW4 | PV489057 | Thermaerobacillus caldiproteolyticus strain SF03 | NR_115200.1 | 99.30% |

| NW1/NW3 | PV489066 | Anoxybacillus gonensis strain G2 | NR_025667.1 | 96.85% |

| NW6/MD2 | PV489038 | Bacillus licheniformis strain ATCC 14580 | NR_074923.1 | 99.71% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).