Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- A detailed overview of organizational network security challenges and the role of policy enforcement in mitigating internal and external threats.

- Identification of key limitations in existing network scanners regarding policy violation detection, auditability, and continuous compliance assurance.

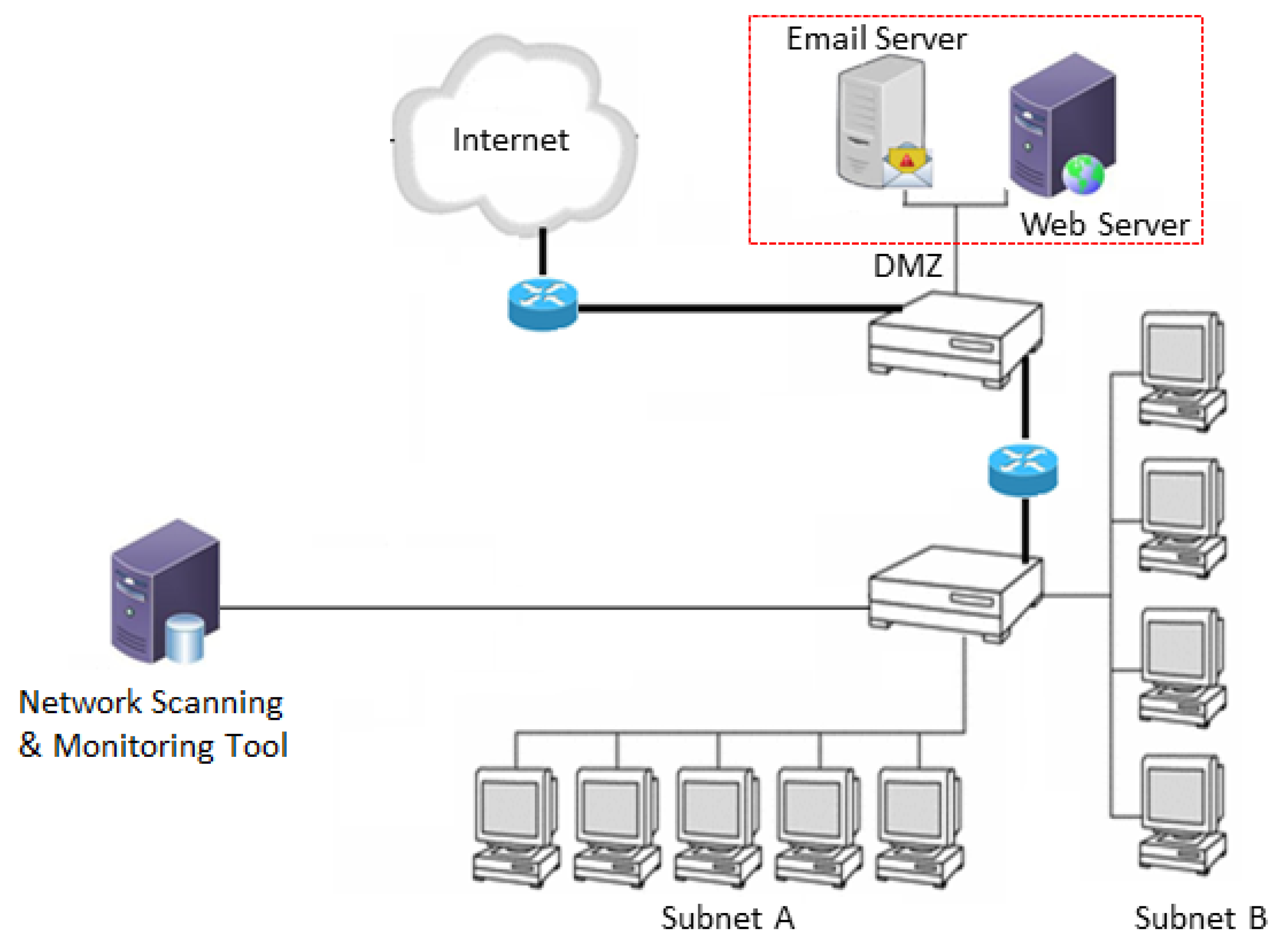

- Proposed a policy-aware network scanning and monitoring framework (BENSAM) that integrates device profiling, user activity monitoring, traffic analysis, and network forensics into a unified architecture.

- Formulation of a structured database model supporting asset-based scanning, scheduled execution, report generation, and vulnerability remediation planning.

- Integration of a permissioned blockchain (Hyperledger Fabric) to enable immutable logging, secure audit trails, and decentralized verification of policy compliance through smart contracts.

- Development and public release of a working prototype demonstrating the end-to-end operation of BENSAM, including scanning, profiling, policy enforcement, blockchain anchoring, and automated report generation.

- Comparative analysis of BENSAM against traditional enforcement and monitoring techniques, emphasizing its scalability, automation, and trustworthiness.

2. Literature Review

3. Network Vulnerabilities, Attacks, and Policy Enforcement Methods

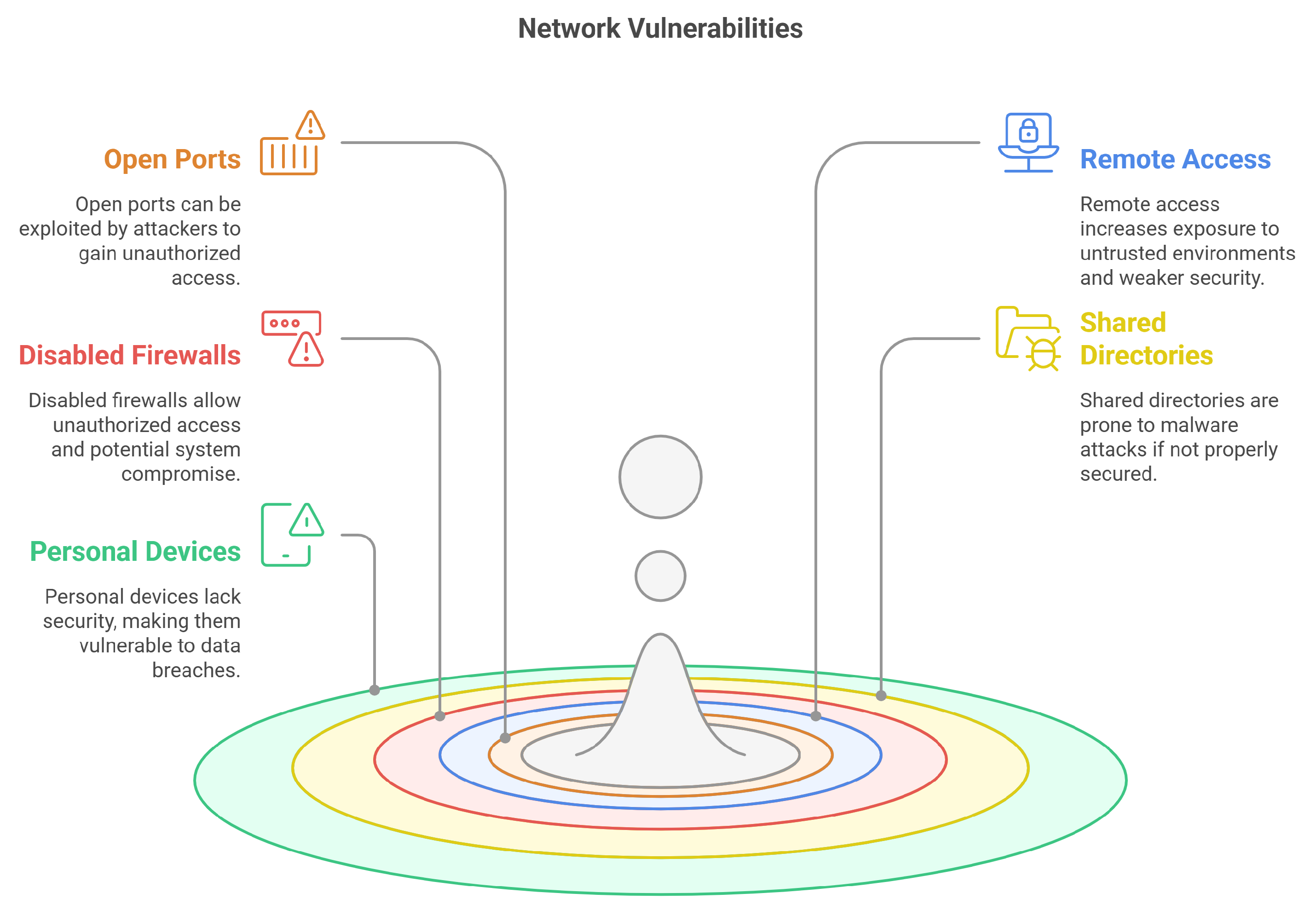

3.1. Common Network Vulnerabilities

3.1.1. Open Ports

3.1.2. Remote Access

3.1.3. Disabled Firewall

3.1.4. Shared Directories

3.1.5. Personal Devices

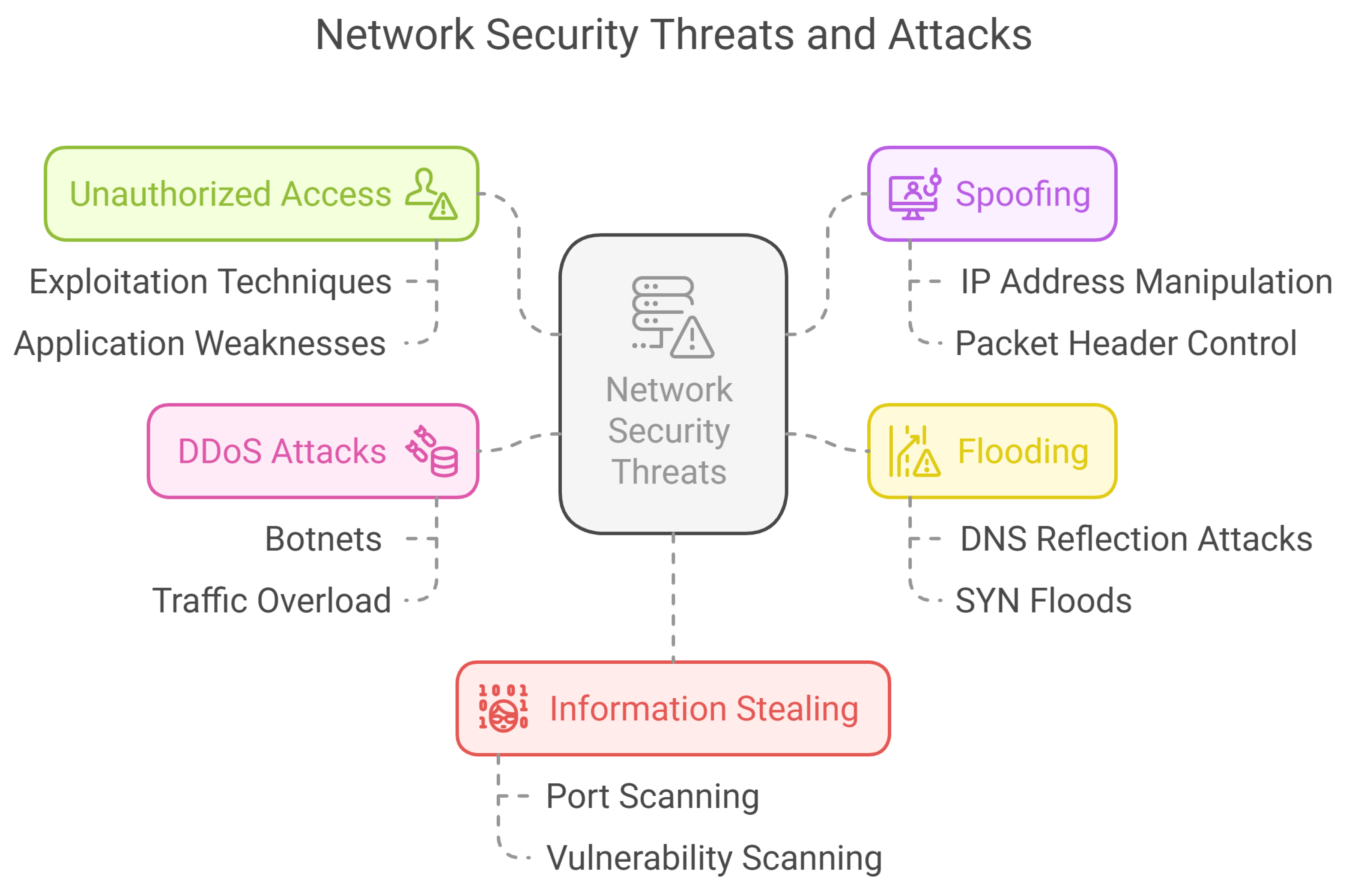

3.2. Common and Emerging Attacks via Network

3.2.1. Unauthorized Access

3.2.2. Spoofing

3.2.3. Flooding

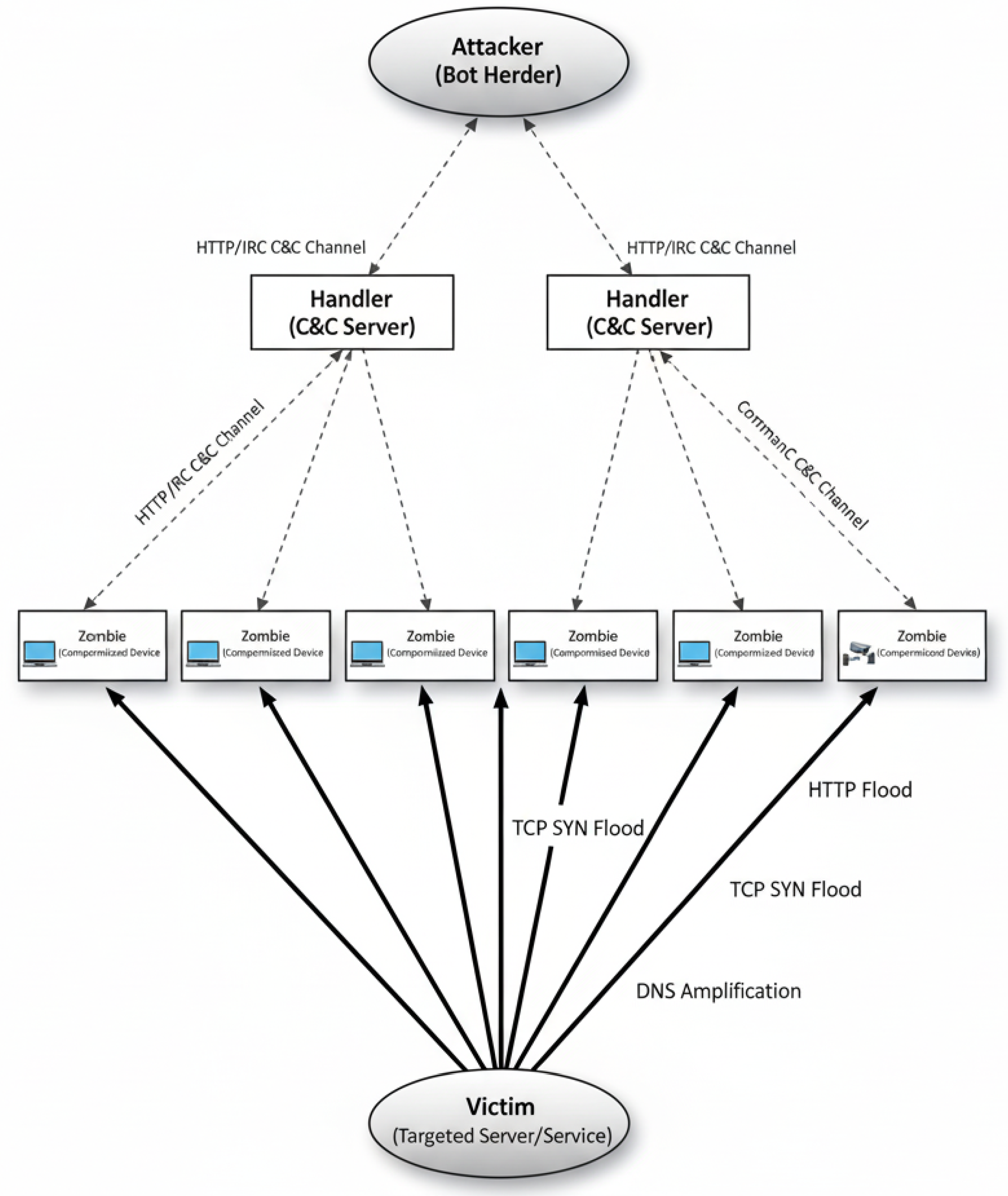

3.2.4. Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) Attack

- The intruder gathers information about network configuration through port scanners to recognize existing weaknesses in the network.

- The intruder exploits such vulnerabilities to launch the attack over the organization’s network.

- In case of a successful attempt of attack, the attacker further installs and sets up additional software to manage uninterrupted network access channels.

- Finally, the intruder struggles to wash-out any remaining evidence that may be left due to the earlier actions. At this stage, daemons restarted that crashed during the 2nd phase, logs were deleted and various actions were taken accordingly.

3.2.5. Information Stealing

3.2.6. Emerging AI-Driven Threats

3.3. Policy Enforcement Methods

3.3.1. Guidelines

3.3.2. OS Hardening

3.3.3. Agent-Based Enforcement

3.3.4. Restriction through Software Defined Networking

3.3.5. Blockchain-Based Policy Enforcement

3.4. Advanced AI-Driven Network Attacks

3.4.1. Adversarial Attacks on Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS)

3.4.2. Data Poisoning Attacks on Network Anomaly Detection Systems

3.4.3. Transformer-Based Evasion Attacks

3.4.4. Relevance to Blockchain-Enhanced Policy Enforcement

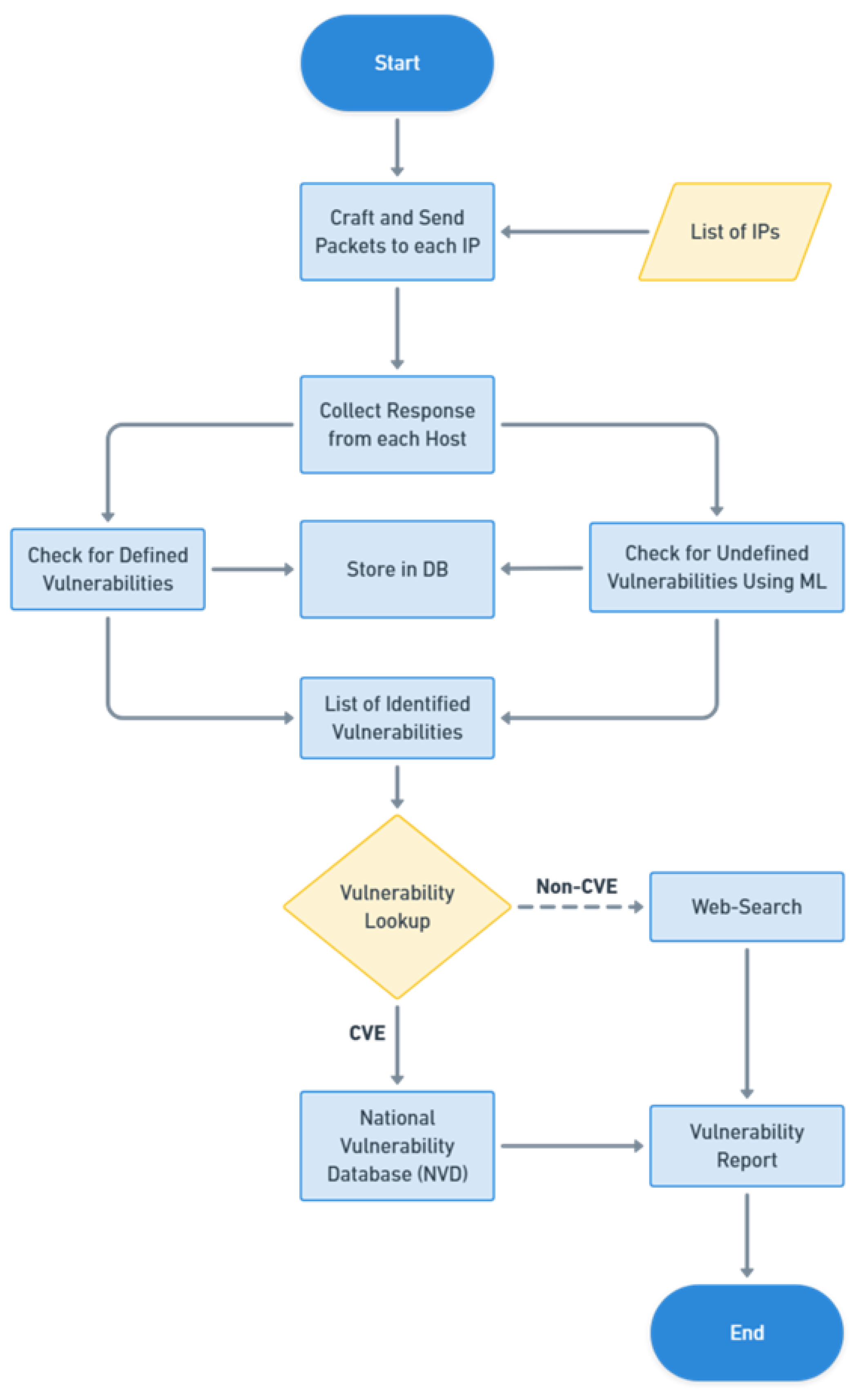

4. Basic Features of a Network Scanner

4.1. IP Scan

4.2. Port Scan

4.2.1. Open Scan

4.2.2. Half-Open Scan

4.2.3. Stealth Scan

4.3. Banner Grabbing/OS Detection

4.4. Server Recognition

4.5. Vulnerability Scan

5. Security Aspects Discoverable via Scanner

5.1. Firewall Status

5.2. Remote Access Status

5.3. Shared Directories

5.4. Malicious Services with Open Ports

5.5. Virtual Machines Recognition

5.6. IP Conflicts

5.7. Wake on LAN

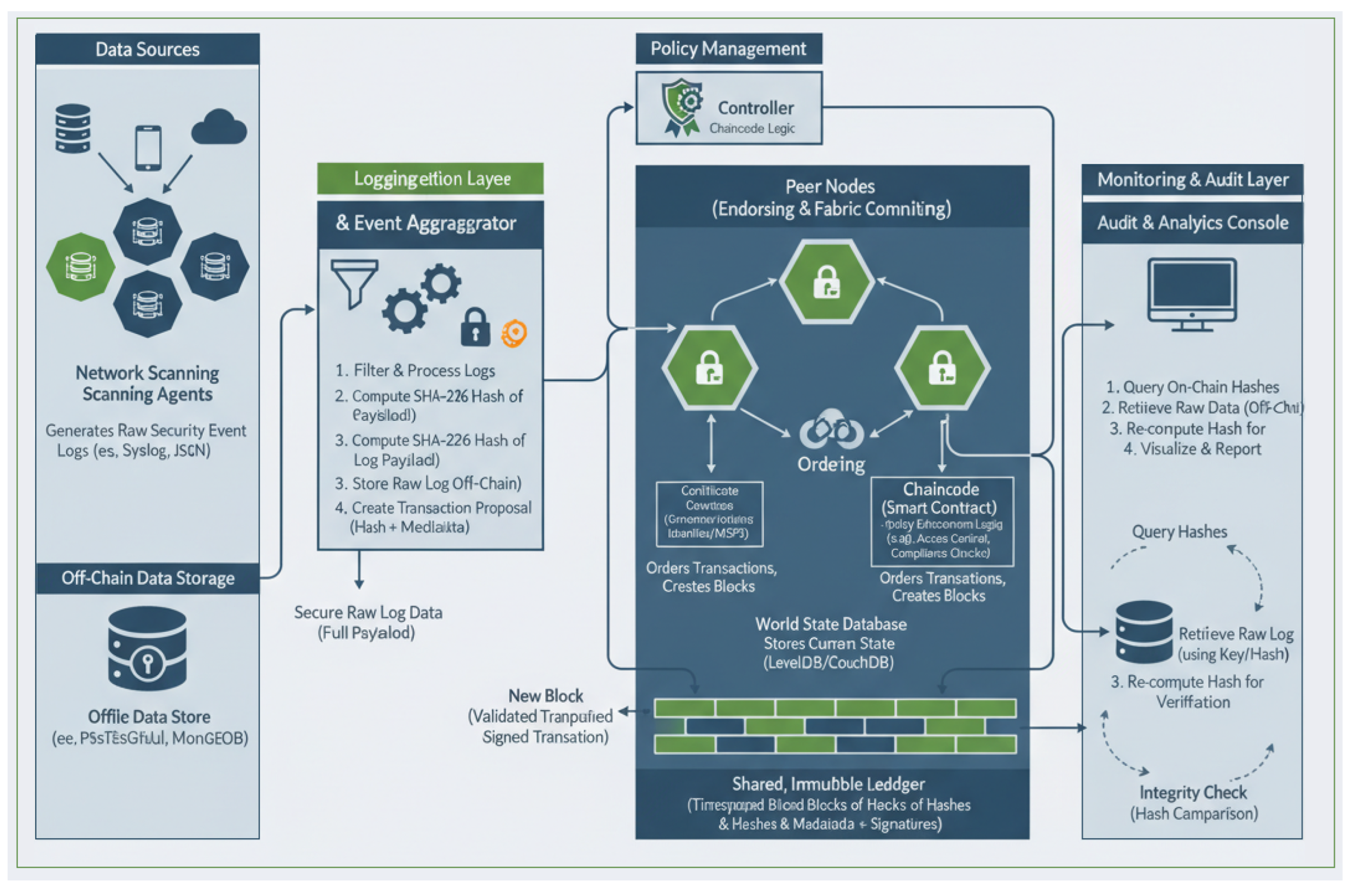

6. Blockchain-Enhanced Network Scanning and Monitoring (BENSAM) Framework

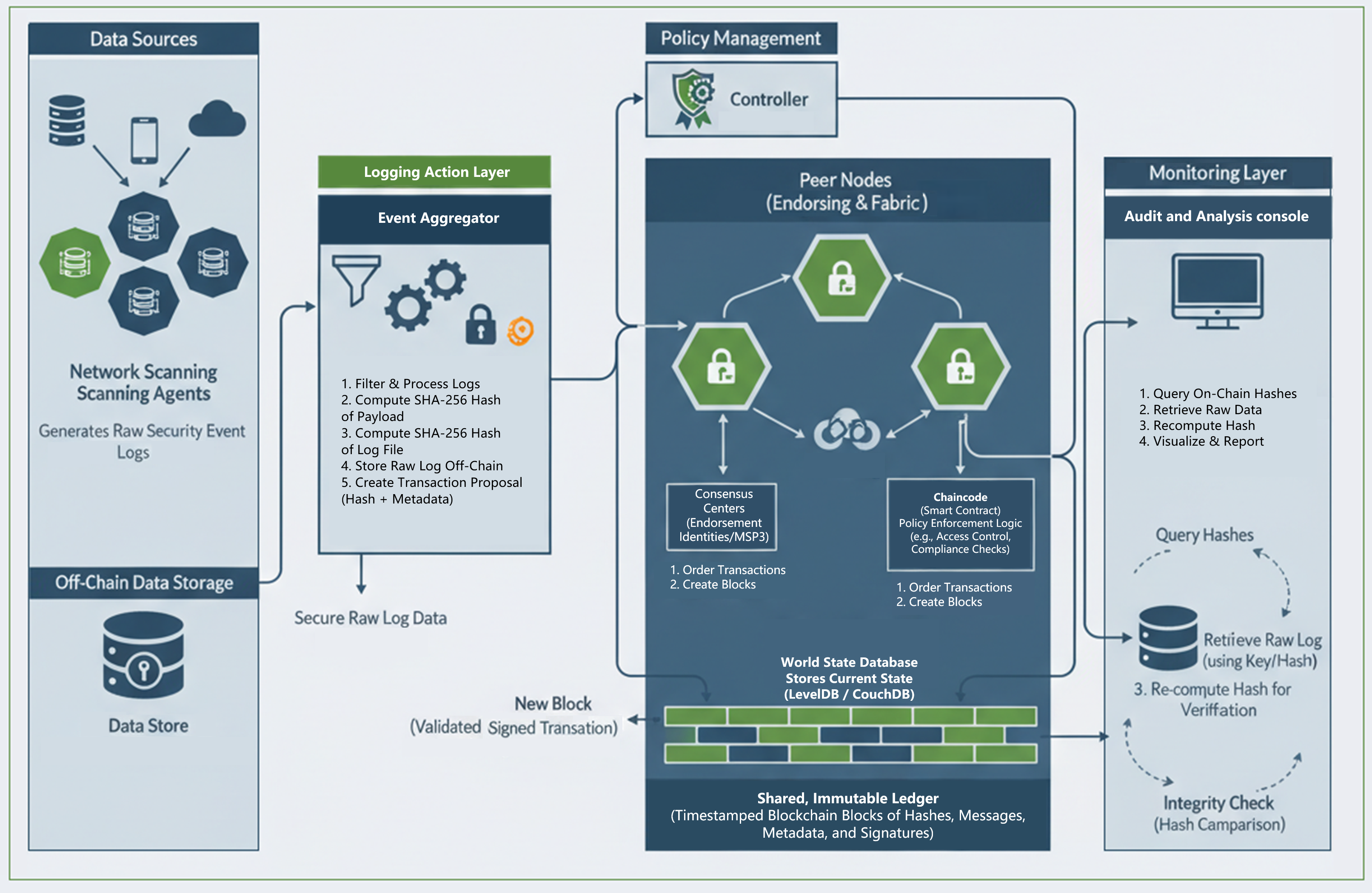

- Network Scanning Agents: These are the data collection endpoints, deployed on servers, hosts, and network devices to continuously monitor for security-relevant activities.

- Logging Service/Event Aggregator: This component acts as the data ingestion gateway, receiving raw events from the agents, processing them, and preparing them for both on-chain and off-chain storage.

- Policy Controller: A centralized management plane that defines and orchestrates the security and compliance policies that govern the network.

- Hyperledger Fabric Network: The core DLT foundation of the framework, comprising Peers (who maintain the ledger and execute transactions), an Ordering Service (which validates and orders transactions), and a Certificate Authority (CA) that manages identities.

- Off-Chain Data Store: A separate, highly scalable database (e.g., a relational or document database) used to store the full, raw log payloads and other large data assets.

- Audit and Analytics Console: A user-facing interface for security analysts and auditors to query event logs, visualize data, and verify the integrity and compliance of recorded events.

| Algorithm 1:Blockchain-Enhanced Network Scanning and Monitoring Algorithm with Immutable Logging and Smart Contract-Based Policy Enforcement |

|

6.1. Immutable Logging and Hybrid Storage Architecture

- Device profiling data (e.g. device types, MAC/IP addresses, OS/software) are hashed and committed to the blockchain to ensure historical integrity.

- Traffic monitoring summaries such as packet metadata, are logged immutably to enable post-event validation and auditing.

- Policy compliance results and enforcement actions are recorded on-chain to create verifiable compliance histories.

6.2. Smart Contract Role in Security Automation

- Initiating scan operations periodically or in response to specific triggers (e.g., new device discovery),

- Verifying device configurations and usage behavior against predefined policy templates,

- Logging violations and generating tamper-proof alerts,

- Triggering enforcement mechanisms, such as isolating non-compliant devices or escalating issues to administrators.

6.3. Alignment with Security Standards

- AU-2 (Audit Events): Immutable blockchain records of scan and enforcement events,

- SI-4 (System Monitoring): Continuous tracking of network activity via trusted smart contracts,

- SC-12 (Cryptographic Key Establishment): Secure peer and user identity validation using digital certificates,

- SC-28 (Protection of Information at Rest): Cryptographic integrity of off-chain data via hashed blockchain references.

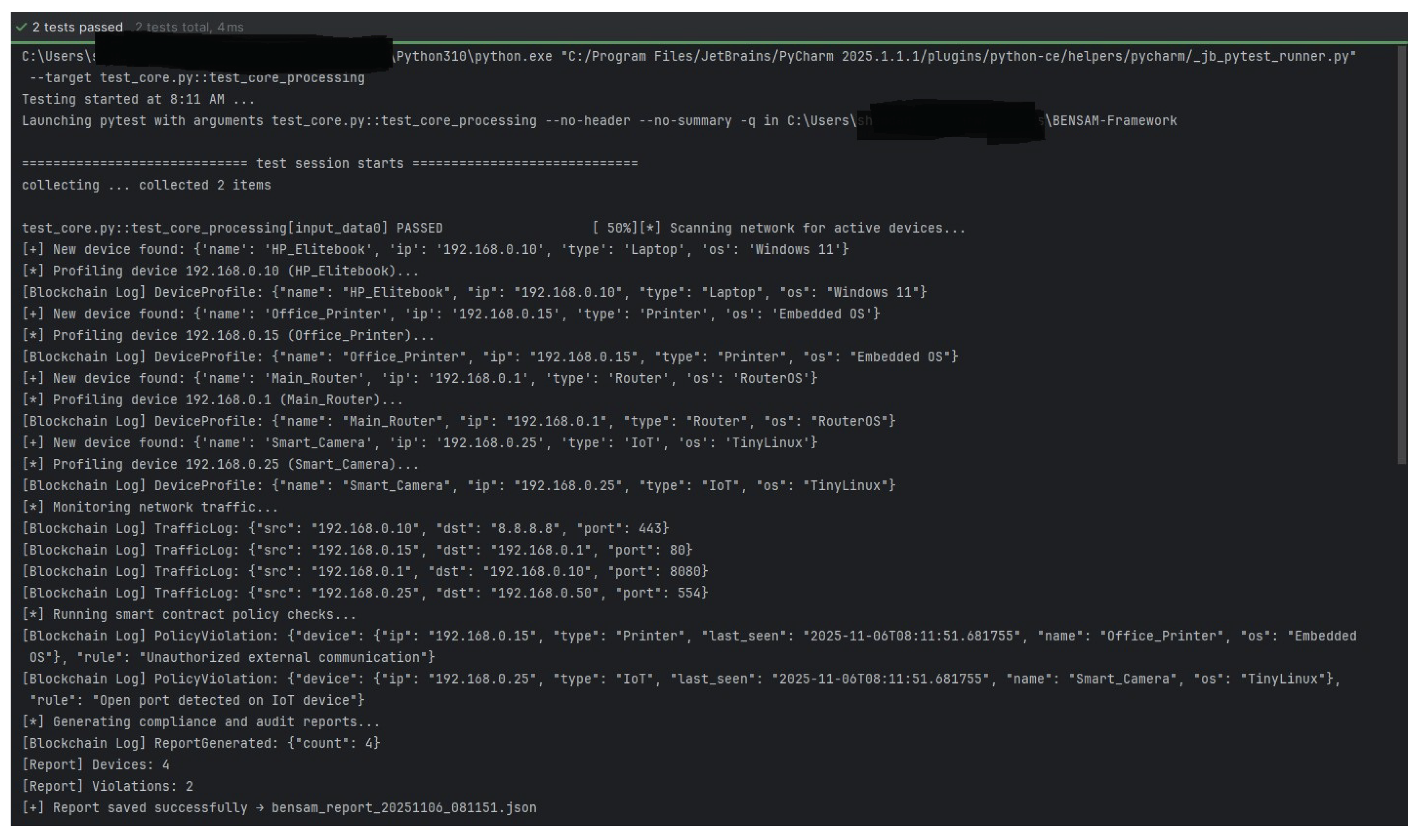

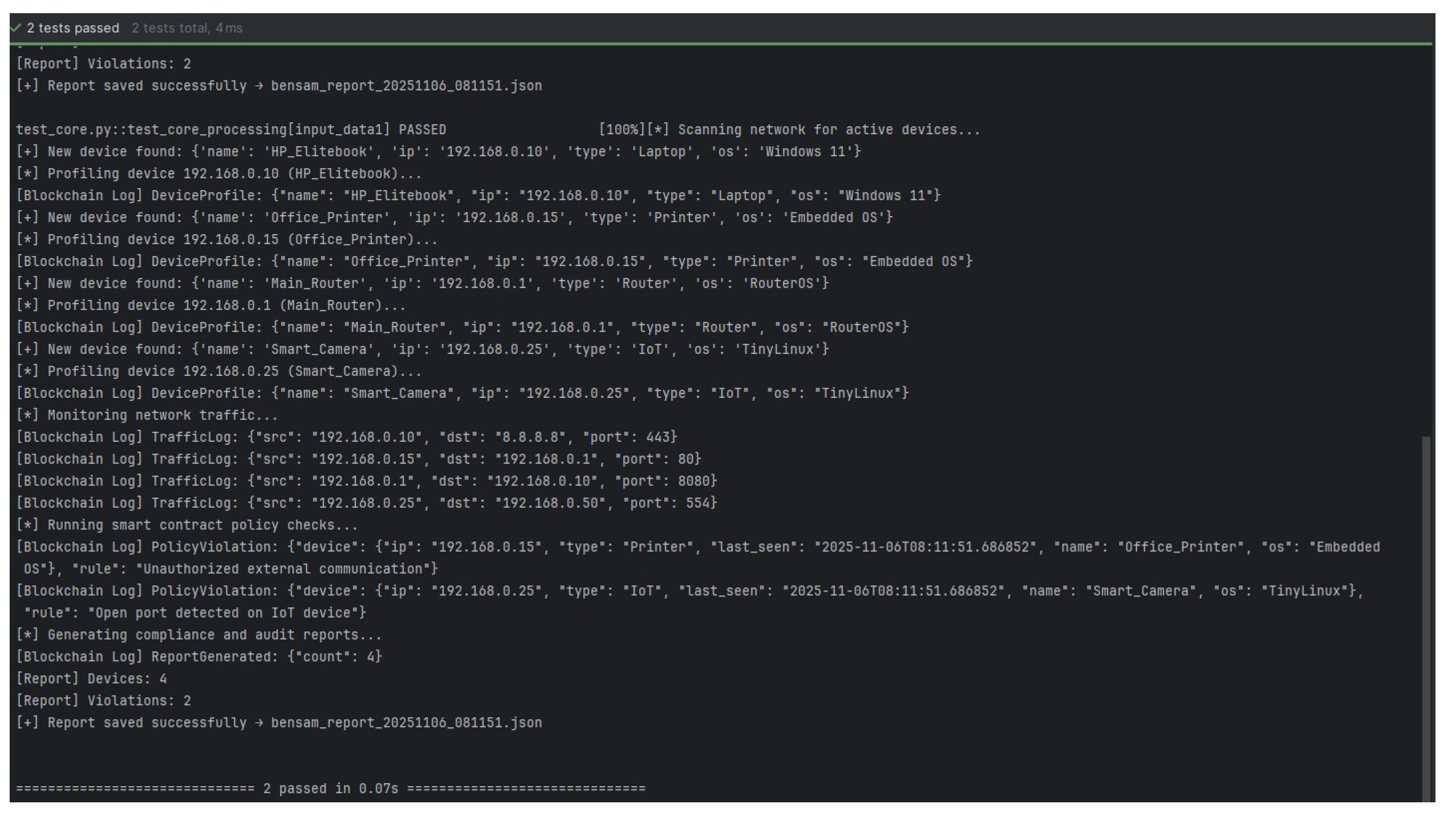

6.4. Implementation and Preliminary Validation

6.5. Feasibility and Future Directions

- Event batching and aggregation prior to blockchain submission,

- Selective on-chain recording of high-value metadata only,

- Distributed off-chain storage for log-heavy operations.

6.6. Local Database

6.7. Scheduled Scanning

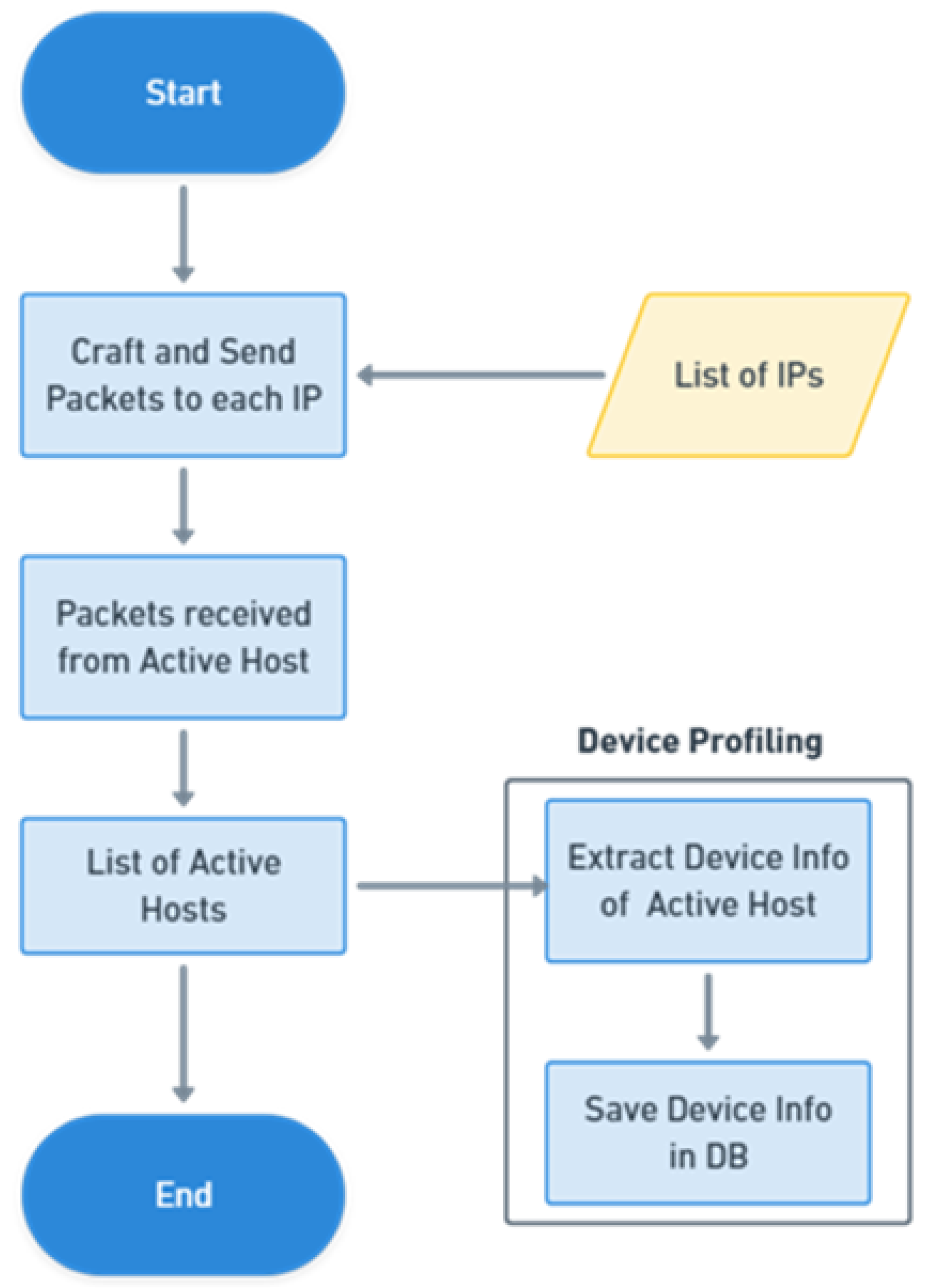

6.8. Device Profiling

6.9. New Device Discovery

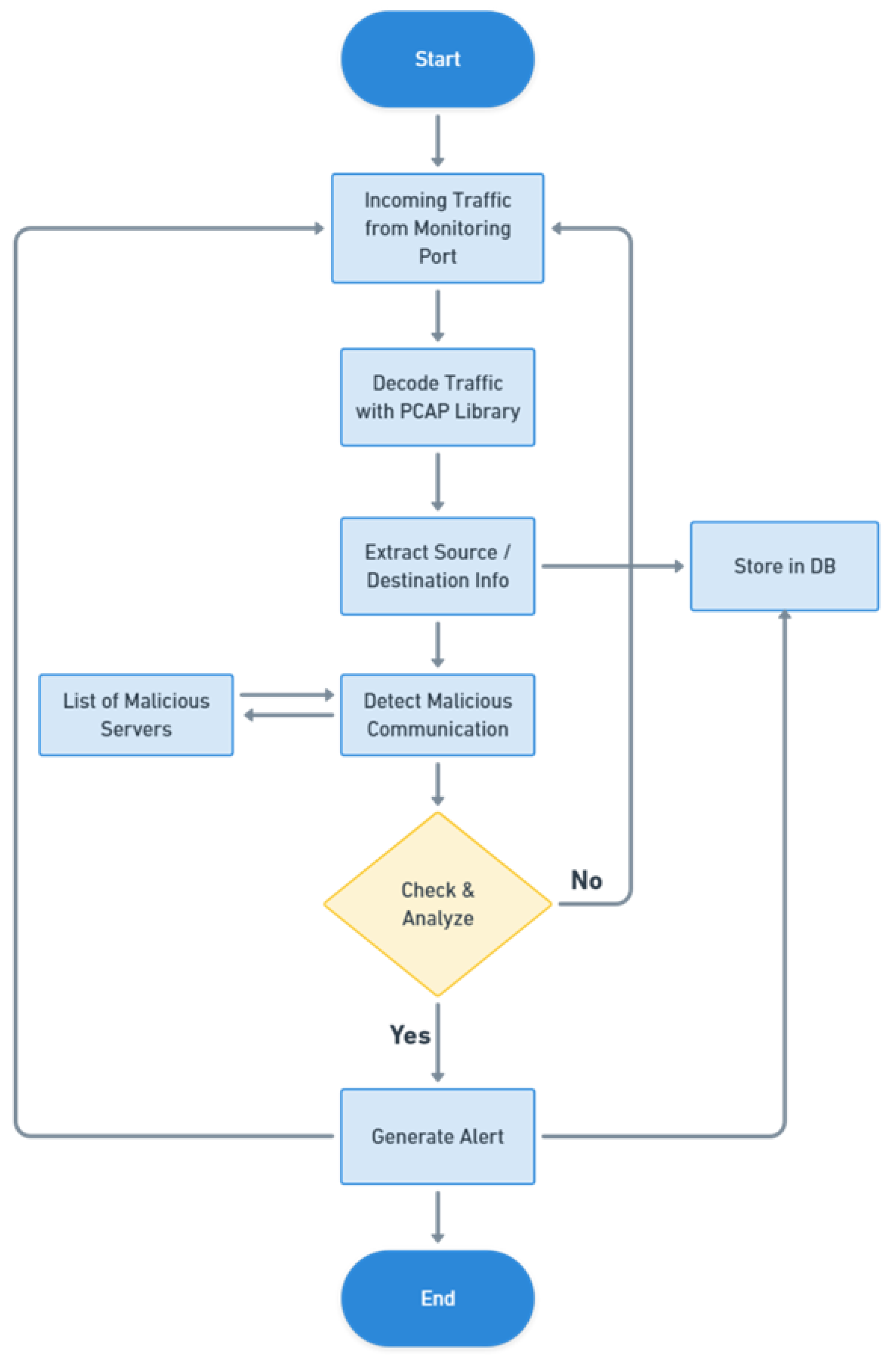

6.10. Traffic Monitoring

6.11. User Activity Logs

6.12. Network Forensics

6.13. IDS/IPS Capability Detection

6.14. Blockchain Integrity Checks

6.15. Smart Enforcement

6.16. Decentralized Compliance

6.17. Algorithmic Complexity Analysis

- NetworkScan: Iterates through each detected device to check profile status and update records. The time complexity is .

- DeviceProfiling: Executed only for new devices, performing OS and software checks, identity mapping, and blockchain logging. Each profiling operation is performed in constant time per device, yielding a worst-case complexity of .

- TrafficMonitoring: Captures and inspects packet headers, storing metadata in both the local database and blockchain. This results in linear complexity with respect to traffic volume: .

- PolicyEnforcement: For every device, a smart contract is triggered to verify compliance. Assuming constant-time contract evaluation per device, the complexity is .

- GenerateReports: Aggregates and formats logs from both storage layers. In a typical scan cycle, the operation scales with both devices and traffic logs, resulting in .

6.18. Customized Report Generation

7. Open Challenges and Future Directions

- A software solution must be developed that implements all the proposed features in the form of a standalone advanced network scanning tool.

- Selecting and integrating a suitable blockchain platform (e.g., Ethereum or Hyperledger) to support smart contracts and ensure performance efficiency.

- Evaluating the proposed scanner in real-world conditions to measure its latency, scalability, and overall security performance.

- Investigating the use of advanced cryptographic techniques, such as zero-knowledge proofs, to enhance privacy without compromising enforcement capability.

- Reducing manual oversight traditionally required in compliance enforcement through automation and smart contract-based policy verification.

- Addressing AI-driven security threats that are becoming more common in modern networks, such as phishing created by language models, intelligent scanning tools, and attacks designed to bypass detection systems. These threats require new detection strategies that can adapt over time and use blockchain logging for tracing unusual behavior.

8. Conclusion

Abbreviations

| SYN | Synchronize |

| CR | Custom Reports |

| UP | User Profiling |

| CC | Common Criteria |

| FWS | Firewall Status |

| OS | Operating System |

| NF | Network Forensics |

| IP | Internet Protocol |

| PE | Policy Enforcement |

| SS | Scheduled Scanning |

| DNS | Domain Name System |

| TM | Traffic Monitoring |

| SD | Structured Database |

| IDSE | IDS/IPS Evaluation |

| VMD | Three letter acronym |

| RDS | Remote Desktop Status |

| VD | Vulnerability Detection |

| UDP | User Datagram Protocol |

| NAC | Network Access Control |

| VMD | Virtual Machine Detection |

| VMD | Virtual Machine Detection |

| ARP | Address Resolution Protocol |

| SDN | Software-Defined Networking |

| TCP | Transmission Control Protocol |

| MPLS | Multiprotocol Label Switching |

| EDR | Endpoint Detection and Response |

| ICMP | Internet Control Message Protocol |

| RARP | Reverse Address Resolution Protocol |

| FIPS | Federal Information Processing Standard |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| BENSAM | Blockchain-Enhanced Network Scanning and Monitoring |

References

- Douligeris, C.; Mitrokotsa, A. DDoS Attacks and Defense Mechanisms: Classification and State-of-the-Art. Computer Science Review 2022, 44, 100458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, B.; Ahmed, M.; Zahra, M.; Hassan, F.; Iqbal, M.A.; Muhammad, Z. A survey of cybersecurity laws, regulations, and policies in technologically advanced nations: A case study of Pakistan to bridge the gap. International Cybersecurity Law Review 2024, 5, 533–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, Z.; Straub, J. An Analysis of Cyber Threats and the Protective Role of Cyber Insurance in the US Market. In Proceedings of the World Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering & Applied Computing. Springer, 2024, pp. 259–272.

- Dissanayake, N.; Jayatilaka, A.; Zahedi, M.; Babar, M.A. Software security patch management-A systematic literature review of challenges, approaches, tools and practices. Information and Software Technology 2022, 144, 106771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Kawshik, K.R.; Sourav, A.A.; Gaji, A.A. Advanced Network Scanning. American Journal of Engineering Research (AJER) 2016, 5, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Buczak, A.L.; Guven, E. A Survey of Data Mining and Machine Learning Methods for Cyber Security Intrusion Detection. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2021, 23, 1121–1153. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.W.; Fritsch, E.J.; Liederbach, J. Digital crime and digital terrorism; Prentice Hall Press, 2014.

- Zhang, C.; Hu, G.; Chen, G.; Sangaiah, A.K.; Zhang, P.; Yan, X.; Jiang, W. Towards a SDN-based integrated architecture for mitigating IP spoofing attack. IEEE Access 2017, 6, 22764–22777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity, Version 1.1. https://www.nist.gov/cyberframework/csf-11-archive, 2018. Accessed on 5 Jan 2025.

- Nmap Project. Zenmap—Official Cross-Platform Nmap Security Scanner GUI. https://nmap.org/zenmap/, 2024. Accessed on 29 November 2024.

- Sarker, I.H.; Kayes, A.; Badsha, S.; Alqahtani, H.; Watters, P.; Ng, A. Cybersecurity data science: an overview from machine learning perspective. Journal of Big data 2020, 7, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdani, S.W.A.; Abbas, H.; Janjua, A.R.; Shahid, W.B.; Amjad, M.F.; Malik, J.; Murtaza, M.H.; Atiquzzaman, M.; Khan, A.W. Cybersecurity standards in the context of operating system: Practical aspects, analysis, and comparisons. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, D.; Callegati, F.; Melis, A.; Prandini, M. Security network policy enforcement through a SDN framework. In Proceedings of the 2018 28th International Telecommunication Networks and Applications Conference (ITNAC). IEEE, 2018, pp. 1–4.

- Khan, A.A.; Laghari, A.A.; Shaikh, Z.A.; Dacko-Pikiewicz, Z.; Kot, S. Internet of Things (IoT) security with blockchain technology: A state-of-the-art review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 122679–122695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Hosen, A.S.; Yoon, B. Blockchain security attacks, challenges, and solutions for the future distributed iot network. Ieee Access 2021, 9, 13938–13959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotohi, R.; Aliee, F.S. Securing communication between things using blockchain technology based on authentication and SHA-256 to improving scalability in large-scale IoT. Computer Networks 2021, 197, 108331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Babbar, H.; Srivastava, G.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Dhiman, G. Security framework for internet-of-things-based software-defined networks using blockchain. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 10, 6074–6081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, S.J.; Sung, W.T. Employing blockchain technology to strengthen security of wireless sensor networks. IEEe Access 2021, 9, 72326–72341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Bourouis, S.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Hadjouni, M.; Shaikh, Z.A.; Laghari, A.A.; Elmannai, H.; Dhahbi, S. Data security in healthcare industrial internet of things with blockchain. IEEE Sensors Journal 2023, 23, 25144–25151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Borah, M.D.; Namasudra, S. Improving security of medical big data by using Blockchain technology. Computers & Electrical Engineering 2021, 96, 107529. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.C.; Pathirana, P.N.; Ding, M.; Seneviratne, A. BEdgeHealth: A decentralized architecture for edge-based IoMT networks using blockchain. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2021, 8, 11743–11757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, R.; Verma, A.; Gupta, P. D-BLAC: A dual blockchain-based decentralized architecture for authentication and communication in VANET. Expert Systems With Applications 2024, 237, 121461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, J. Security of Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks using blockchain: A comprehensive review. Vehicular Communications 2022, 34, 100458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendiab, G.; Hameurlaine, A.; Germanos, G.; Kolokotronis, N.; Shiaeles, S. Autonomous vehicles security: Challenges and solutions using blockchain and artificial intelligence. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2023, 24, 3614–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.S.; Khan, S.; Rehman, A.; Abbas, S.; Khan, M.A.; Hwang, S.O. Blockchain-based smart home networks security empowered with fused machine learning. Sensors 2022, 22, 4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hızal, S.; Akhter, A.S.; Çavuşoğlu, Ü.; Akgün, D. Blockchain-based IoT security solutions for IDS research centers. Internet of Things 2024, 27, 101307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Qiao, L.; Hossain, M.S.; Choi, B.J. Analysis of using blockchain to protect the privacy of drone big data. IEEE network 2021, 35, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Z. Effective methods and performance analysis of a satellite network security mechanism based on blockchain technology. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 113558–113565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, S.; Khare, A.; Dwivedi, A.D.; Singh, R. Securing IoT devices: A novel approach using blockchain and quantum cryptography. Internet of things 2024, 25, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyeer-E-Ferdoush. ; Rahman, H.; Hasan, M. A convenient way to mitigate DDoS TCP SYN flood attack. Journal of Discrete Mathematical Sciences and Cryptography 2022, 25, 2069–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.J.; Chen, Q.A.; Lin, Y.; Kong, C.; Mao, Z.M. Open doors for bob and mallory: Open port usage in android apps and security implications. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P). IEEE, 2017, pp. 190–203.

- Bhakthavatsalam, P.; Malarkodi, B. Analysis of network infrastructure threats using SonicWALL analyser. In Proceedings of the 2016 3rd International Conference on Devices, Circuits and Systems (ICDCS). IEEE, 2016, pp. 6–9.

- Rahman, A.; Kawshik, K.R.; Sourav, A.A.; Gaji, A.A. Advanced Network Scanning. American Journal of Engineering Research (AJER) 2016, 5, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. Classification and detection of computer intrusions. PhD thesis, PhD thesis, Purdue University, 1995.

- Mohammed, S.A. Designing Rules to Implement Reconnaissance and Unauthorized Access Attacks for Intrusion Detection System. Iraqi Journal of Information & Communications Technology 2019, 2, 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, J.Z.; Cimato, S.; Muhammad, Z. A Sharded Blockchain Architecture for Healthcare Data. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 48th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1794–1799.

- Lichtblau, F.; Streibelt, F.; Krüger, T.; Richter, P.; Feldmann, A. Detection, classification, and analysis of inter-domain traffic with spoofed source IP addresses. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2017 Internet Measurement Conference, 2017, pp. 86–99.

- Singh, R.; Thakur, K.; Singh, G.; Gupta, S. Prevention of IP spoofing attack in cyber using artificial Bee colony and artificial neural network. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Advanced Informatics for Computing Research, 2019, pp. 1–10.

- Verisign, Inc.. Q4 2016 DDoS Trends Report: 167 Percent Increase in Average Peak Attack Size. https://blog.verisign.com/security/q4-2016-ddos-trends-report-167-percent-increase-average-peak-attack-size/, 2017.

- Deka, R.K.; Bhattacharyya, D.K.; Kalita, J.K. Granger Causality in TCP Flooding Attack. IJ Network Security 2019, 21, 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.A.; Zaman, N.A.K. Attack Intention Recognition: A Review. IJ Network Security 2017, 19, 244–250. [Google Scholar]

- Baishya, R.C.; Hoque, N.; Bhattacharyya, D.K. DDoS Attack Detection Using Unique Source IP Deviation. IJ Network Security 2017, 19, 929–939. [Google Scholar]

- Sattar, I.; Shahid, M.; Abbas, Y. A review of techniques to detect and prevent distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack in cloud computing environment. International Journal of Computer Applications 2015, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.R.; Hwang, M.S. A New Investigation Approach for Tracing Source IP in DDoS attack from Proxy Server. In Proceedings of the ICS, 2014, pp. 850–857.

- Jung, J.; et al. Real-time detection of malicious network activity using stochastic models. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2006.

- Arshad, J.; Talha, M.; Saleem, B.; Shah, Z.; Zaman, H.; Muhammad, Z. A Survey of Bug Bounty Programs in Strengthening Cybersecurity and Privacy in the Blockchain Industry. Blockchains 2024, 2, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoro, N.; Gonçalves, L.; Serrão, C. NIST CyberSecurity Framework Compliance: A Generic Model for Dynamic Assessment and Predictive Requirements. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Trustcom/BigDataSE/ISPA. IEEE, 2015, Vol. 1, pp. 418–425.

- Greenbone Networks GmbH. OpenVAS—Open Vulnerability Assessment Scanner. https://www.openvas.org/, 2024.

- Irfan, M.; Ali, S.T.; Ijlal, H.S.; Muhammad, Z.; Raza, S. Exploring the synergistic effects of blockchain integration with IoT and AI for enhanced transparency and security in global supply chains.

- Islam, M.B.E.; Haseeb, M.; Batool, H.; Ahtasham, N.; Muhammad, Z. AI threats to politics, elections, and democracy: a blockchain-based deepfake authenticity verification framework. Blockchains 2024, 2, 458–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daidone, F.; Carminati, B.; Ferrari, E. Blockchain-based privacy enforcement in the IoT domain. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing 2021, 19, 3887–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Chen, Z. A Systematic Study of Adversarial Attacks Against Network Intrusion Detection Systems. Electronics 2024, 13, 5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Data Poisoning in Network Anomaly Detection Systems. PhD thesis, Carnegie Mellon University, 2024.

- Du, W.; Xue, J.; Yang, X.; Guo, W.; Gu, D.; Han, W. TransfficFormer: A novel Transformer-based framework to generate evasive malicious traffic. Knowledge-Based Systems 2025, p. 113546.

- Schiffman, M. The libnet packet construction library. The Million Packet March 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W. Design and implement of common network security scanning system. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Symposium on Intelligent Ubiquitous Computing and Education. IEEE, 2009, pp. 148–151.

- Calderon, P. Nmap Network Exploration and Security Auditing Cookbook: Network discovery and security scanning at your fingertips; Packt Publishing Ltd, 2021.

- Jacobson, V.; McCanne, S. libpcap: Packet capture library. Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 2009.

- Shuguang, W.; Gaogang11, X. libpcap-MT: A General Purpose Packet Capture Library with Multi-Thread. Journal of Computer Research and Development 2011, 5, 756–764. [Google Scholar]

- McCanne, S.; Jacobson, V. The BSD Packet Filter: A New Architecture for User-level Packet Capture. In Proceedings of the USENIX winter, 1993, Vol. 46.

- Nmap: The Network Mapper, A Powerful Open Source Tool for Network Discovery and Security Auditing. https://nmap.org/, 2024.

- Shah, M.; Ahmed, S.; Saeed, K.; Junaid, M.; Khan, H.; et al. Penetration Testing Active Reconnaissance Phase–Optimized Port Scanning With Nmap Tool. In Proceedings of the 2019 2nd International Conference on Computing, Mathematics and Engineering Technologies (iCoMET). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–6.

- Lyon, G. Nmap: The network mapper–Free security scanner. Nmap. org 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, N.; Jadav, N.; Dutiya, N.; Joshi, D. Using Honeypots for ICS Threats Evaluation. In Recent Developments on Industrial Control Systems Resilience; Springer, 2020; pp. 175–196.

- Advanced IP Scanner — Fast and Reliable Network Scanning Tool. https://www.advanced-ip-scanner.com/, 2024.

- Angry IP Scanner Project. Angry IP Scanner — Fast and Friendly Network Scanner. https://angryip.org/, 2023.

- Tian, D. Angry IP Scanner: A Lightweight and Efficient Network Scanning Tool for Cybersecurity Applications. Cyber Security and Information 2017, p. 87.

- Eusing Software. Free IP Scanner by Eusing — A Fast and Simple Network Scanning Tool. https://www.eusing.com/ipscan/free_ip_scanner.htm, 2022.

- Baloch, R. Ethical hacking and penetration testing guide; CRC Press, 2017.

- The GNU Netcat, A Versatile Networking Utility for Reading and Writing Data Across Networks. http://netcat.sourceforge.net/, 2021.

- Kurth, M.; Gras, B.; Andriesse, D.; Giuffrida, C.; Bos, H.; Razavi, K. NetCAT: Practical Cache Attacks from the Network, 2020.

- LanSweeper. LanSweeper IP Scanner — Comprehensive Network Scanning and Asset Discovery Tool. https://www.lansweeper.com/feature/ip-scanner/, 2022.

- Erlandson, R. Finding Help and Keeping Up with Changing Technology in Libraries. Technology for Small and One-Person Libraries: A LITA Guide 2013, 21, 125. [Google Scholar]

- HAFSAOUI, M.A.; MANSOUR, H. D ’e development of a computer park management application. PhD thesis, Universit ’e Virtual of Tunis, 2019.

- MyLanViewer Network/IP Scanner, User-Friendly Network Discovery and Monitoring Tool. http://www.mylanviewer.com/network-ip-scanner.html, 2020.

- Garcia, H.C. About monitoring the confidentiality of computer systems. Mathematical machines and systems 2015.

- Dandan, T. LAN scan MyLanViewer. Cyber security and information 2017, p. 94.

- Tenable Inc.. Nessus — Industry-Leading Vulnerability Assessment Tool. https://www.tenable.com/products/nessus, 2020.

- Anderson, H. Introduction to Nessus. SecurityFocus 2003. Available at http://www.securityfocus.com/infocus/1741.

- Wijaya, S.A.A. ATCS System Security Audit Using Nessus. ATCS 2017, 7.

- Josephlal, E.F.M.; Adepu, S. Vulnerability Analysis of an Automotive Infotainment System’s WIFI Capability. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 19th International Symposium on High Assurance Systems Engineering (HASE). IEEE, 2019, pp. 241–246.

- Memon, I.; Shaikh, R.A.; Fazal, H.; Tunio, H.; Arain, Q.A. The World of Hacking: A Survey. University of Sindh Journal of Information and Communication Technology 2020, 4, 31–37.

- Zhang, W.; Banescu, S.; Pasos, L.; Stewart, S.; Ganesh, V. MPro: Combining Static and Symbolic Analysis for Scalable Testing of Smart Contract. arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.00570 2019. arXiv:1911.00570 2019.

- Singh, R.R.; Tomar, D.S. Network forensics: detection and analysis of stealth port scanning attack. scanning 2015, 4, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S.K.; Sonker, A. Internet protocol identification number based ideal stealth port scan detection using snort. In Proceedings of the 2016 8th International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Communication Networks (CICN). IEEE; 2016; pp. 422–427. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle, S. Port Scanning Techniques, Tools, and Detection. Cybersecurity Journal 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, M.A.; Ahmed, S.; Mehmood, A.; Shaheen, R.; Dildar, M.S. Vulnerability assessment of operating systems in healthcare: exploitation implications techniques and security. Health Sciences Journal 2024, 2, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitre Corporation. Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) Database. https://cve.mitre.org/, 2022.

- Bonandir, A.; Yussof, S. An analysis of common vulnerability and exposure (CVE) of software products in the year 2016. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology 2018, 112, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisco. What is a firewall? A primer on firewalls. https://www.cisco.com/site/us/en/learn/topics/security/what-is-a-firewall.html, 2025.

| Component | Key Responsibilities | Input/Output |

|---|---|---|

| Network Scanning Agent | Continuously monitors endpoints, servers, and network devices for security events, misconfigurations, and vulnerabilities. | Inputs: Local system/network data. Outputs: Structured raw log data. |

| Logging Service | Acts as the data ingestion point; aggregates and filters raw logs; generates a cryptographic hash of each log; and securely stores the raw data off-chain. | Inputs: Raw log events from agents. Outputs: (1) Hashed log events (sent to blockchain). (2) Full raw logs (sent to off-chain store). |

| Policy Controller | Defines, manages, and updates network security policies. Translates high-level rules into executable chaincode logic for compliance verification. | Inputs: Policy definitions. Outputs: Policy parameters for chaincode. |

| Hyperledger Fabric Network | The distributed ledger for storing immutable, verifiable records of event hashes and metadata. Enforces policies via chaincode and consensus. | Inputs: Hashed transaction proposals. Outputs: Immutable, validated blocks containing event hashes. |

| Off-Chain Data Store | Provides scalable and private storage for the full, raw log payloads and other large data. The primary data is retrieved from here during an audit. | Inputs: Raw log data from the Logging Service. Outputs: Raw log data to the Audit Console (on request). |

| Audit & Analytics Console | Provides a user interface for security analysts and auditors. Queries the blockchain for immutable hashes and retrieves the corresponding raw data from off-chain storage for verification and analysis. | Inputs: Queries from auditors. Outputs: Visualizations, reports, and audit verification. |

| Name | FWS | RDS | VMD | UP | DI | CR | VD | NF | IDSE | SS | SD | PE | TM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMAP | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||

| SolarWinds Scanner | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||

| Advanced IP Scanner | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||

| Angry IP Scanner | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||

| Eusing IP Scanner | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||

| NetCat | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||

| LanSweeper IP Scanner | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||

| MyLanViewer | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||

| Slitheris Network Discovery | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||

| Proposed Advanced Scanner |

| Open Challenges | Description | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of integrated software solution | There is currently no standalone tool that combines device profiling, scheduled scanning, traffic monitoring, and blockchain-based policy enforcement into a unified system. | Development of a comprehensive network scanning tool |

| Blockchain platform selection | Selecting an appropriate blockchain platform (e.g. Ethereum or Hyperledger) is essential to support smart contracts while maintaining performance efficiency and scalability. | Evaluation and integration of a suitable blockchain platform |

| Performance evaluation in real-world settings | The proposed scanner must be tested under realistic network environments to validate its latency, scalability, and security. | Benchmark testing in operational scenarios |

| Privacy-preserving enforcement | Cryptographic methods like zero-knowledge proofs are needed to enhance user privacy without weakening policy enforcement. | Integration of advanced cryptographic techniques |

| Manual oversight in compliance enforcement | Traditional policy enforcement requires human monitoring, which is error-prone and inefficient. | Automation via smart contracts for policy verification |

| Emerging AI-driven threats | AI-generated phishing, intelligent evasion, and automated reconnaissance are becoming common. These threats are harder to detect using static rules and can bypass traditional defenses. | Use adaptive detection models and blockchain logging to trace unusual activity and improve response |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).