1. Introduction

Contemporary agriculture is increasingly confronted with multifaceted challenges related to food waste and the escalating pressure on natural ecosystems. It is estimated that over 30% of global food production is lost or wasted, while agricultural activities account for nearly 25% of global greenhouse gas emissions [

1]. This situation poses a serious threat to the sustainability of food systems and underscores the urgent need for transformative shifts in both production and consumption patterns. If this trajectory is not reversed, global warming is projected to exceed the 1.5 °C threshold within this century [

2]. In Latin America, under a high-emissions scenario, per capita GDP could decline by up to 3.3% by 2050, exacerbating poverty and food insecurity [

3].

This implies that developing countries are likely to face deepened structural challenges, further aggravated by the persistence of linear production models characterized by intensive input use and high waste generation. Ecuador exemplifies this dynamic, given its strong reliance on agro-export industries—particularly in key value chains such as banana, cocoa, and oil palm. The country continues to struggle with environmental degradation, inefficient resource utilization, waste accumulation, and the underutilization of agro-industrial byproducts, which collectively hinder progress toward sustainable transformation [

4,

5,

6]. Moreover, the intensification of agrochemical use and the absence of comprehensive waste management systems have led to soil degradation, water contamination, and declining soil biodiversity, ultimately undermining Ecuador’s competitiveness in increasingly sustainability-conscious international markets [

7,

8]. From the challenges outlined above, alternative approaches grounded in the principles of circularity and regeneration are emerging as viable solutions. Multicomponent biorefineries represent a promising technological strategy for converting agro-industrial residues into value-added products such as biofertilizers, bioplastics, bioenergy, and other biobased inputs, in alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals [

9]. Within this context, two complementary frameworks converge: (1) the

bioeconomy, which focuses on the sustainable use of biomass and renewable biological resources; and (2) the

circular economy, which seeks to transition from linear models to productive systems that recirculate materials, minimize waste, and foster collaborative innovation [

10,

11].

In Ecuador, it is estimated that approximately 14,000 tons of solid waste are generated daily, of which more than 50% is organic. Yet, only a minimal fraction is effectively recycled [

12]. This figure underscores the country’s lag in adopting circular models, despite their proven potential to reduce emissions, diversify income streams, and generate green employment in strategic sectors. Particularly in the coastal region, favorable conditions exist for the application of closed-loop technologies—such as anaerobic digestion—which could facilitate nutrient cycling, enhance energy efficiency, and reduce ecological pressure on agricultural ecosystems [

13,

14,

15].

Such strategies could be integrated into broader frameworks of industrial symbiosis, drawing inspiration from models like Kalundborg

1, and adapted to Latin American realities through territorial alliances between agroindustry, fisheries, tourism, and other regional sectors [

16]. However, significant gaps remain in the scholarly literature regarding the effective integration of circular economy and bioeconomy principles in rural territories with limited institutional capacity.

Most existing studies tend to focus on isolated technological solutions or on general regulatory frameworks, often overlooking the territorial, social, and organizational conditions that critically shape the sustainable adoption of these approaches within agro-industrial contexts. In response to this gap, the present study adopts a territorial ecosystem perspective—one that integrates multi-actor innovation processes, industrial symbiosis, and resource regeneration—while assessing the practical applicability of these principles through an exploratory analysis of sectoral experiences in Ecuador’s coastal region.

The primary objective is to examine and address the enabling conditions, structural barriers, and collaborative dynamics that influence the integration of circular bioeconomy strategies into productive rural ecosystems. To this end, the study focuses on the banana, cocoa, and African oil palm value chains—selected for their economic significance and latent potential for residual biomass valorization. These cases offer a representative lens through which to understand how circularity and regenerative approaches might be contextually grounded in specific territorial and institutional realities.

2. Methods

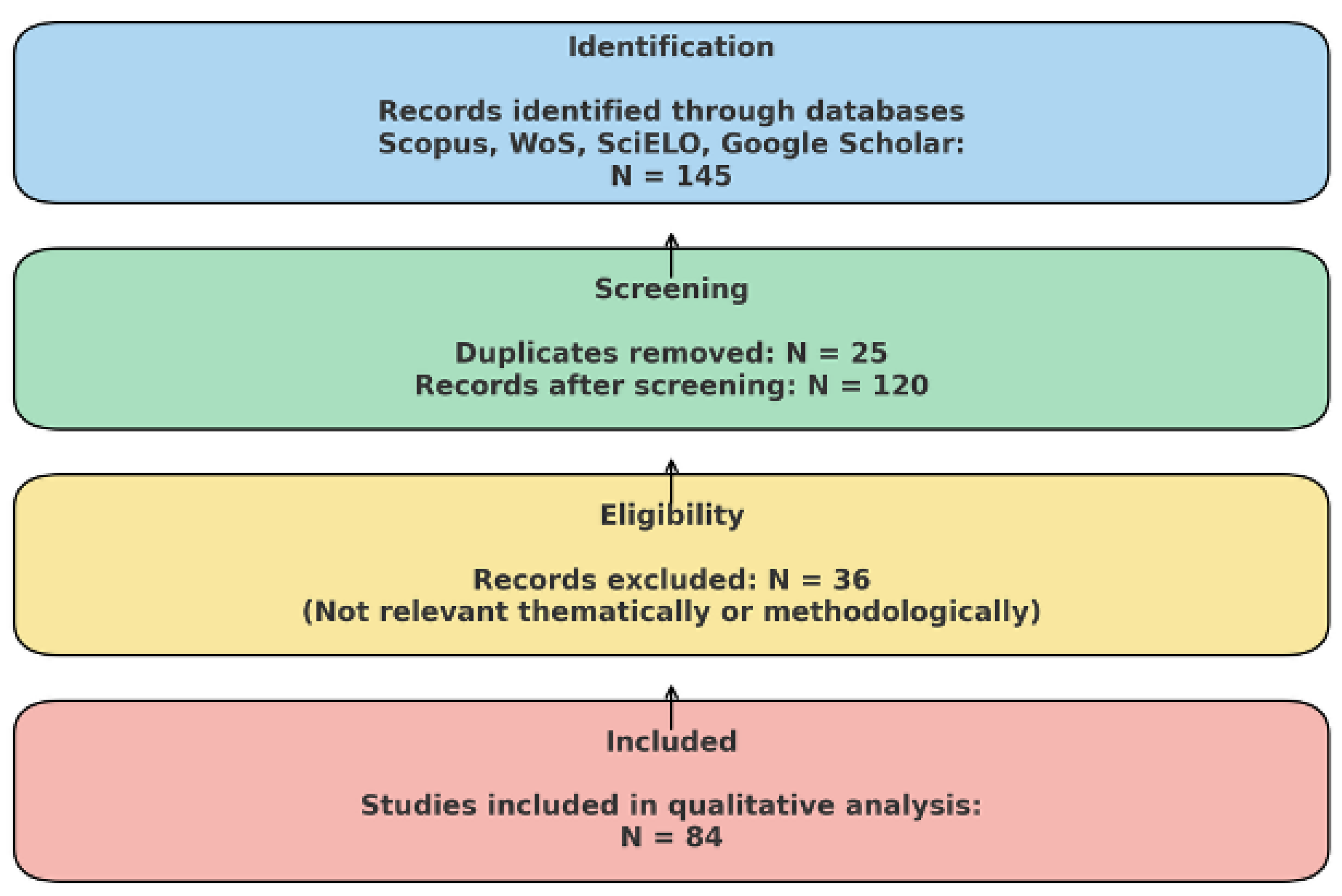

A qualitative research methodology was employed, structured in two complementary phases. This review followed the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines for scoping reviews [

17]. A completed PRISMA checklist is provided in the Supplementary Materials, and the source selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (

Figure 1). The review protocol was not registered.

The first phase consisted of a systematic review of scientific and technical literature, drawing on major academic databases including Scopus, Web of Science, SciELO, and Google Scholar—selected for their relevance in the fields of social, environmental, and economic sciences. The search strategy integrated Boolean operators and a set of targeted keywords in both English and Spanish, such as “circular ecosystems”, “circular economy in agribusiness”, “sustainable innovation”, “bioeconomy”, and “Ecuador”. The review covered the period from 2000 to 2024, ensuring both historical depth and contemporary relevance.

To ensure methodological rigor, the following inclusion criteria were applied:

- (i)

peer-reviewed articles;

- (ii)

direct relevance to circular economy practices in agro-industrial or rural contexts; and

- (iii)

empirical evidence or conceptual models applicable to developing countries.

Studies that adopted exclusively technological approaches without territorial or systemic integration were excluded.

The final selection consisted of 84 documents, including scientific journal articles, specialized books, and reports from multilateral organizations such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), along with institutional literature relevant to the Ecuadorian context. Document analysis was conducted through a qualitative thematic synthesis aimed at identifying conceptual patterns, operational principles, and critical dimensions of circular ecosystems, while distinguishing them from other organizational models such as clusters or linear value chains.

To illustrate the review and source-filtering process, a simplified PRISMA diagram was developed (

Figure 1).

In the second phase, an exploratory analysis was conducted of sectoral and territorial experiences in Ecuador’s coastal region, with a specific focus on three representative agro-industrial value chains: plantain, cocoa, and African oil palm. The selection of these sectors was based on criteria such as their economic importance to the country, increasing international pressure to meet sustainability standards, and their high levels of residual biomass generation, as previously noted.

The unit of observation was defined as rural productive ecosystems where public, private, and community actors converge around the production, transformation, and valorization of agro-industrial waste. This exploratory analysis employed a triangulation of secondary sources—including academic literature, technical sectoral studies, and institutional databases—and aimed to identify structural barriers, enabling conditions, circular adoption practices, and opportunities for scaling.

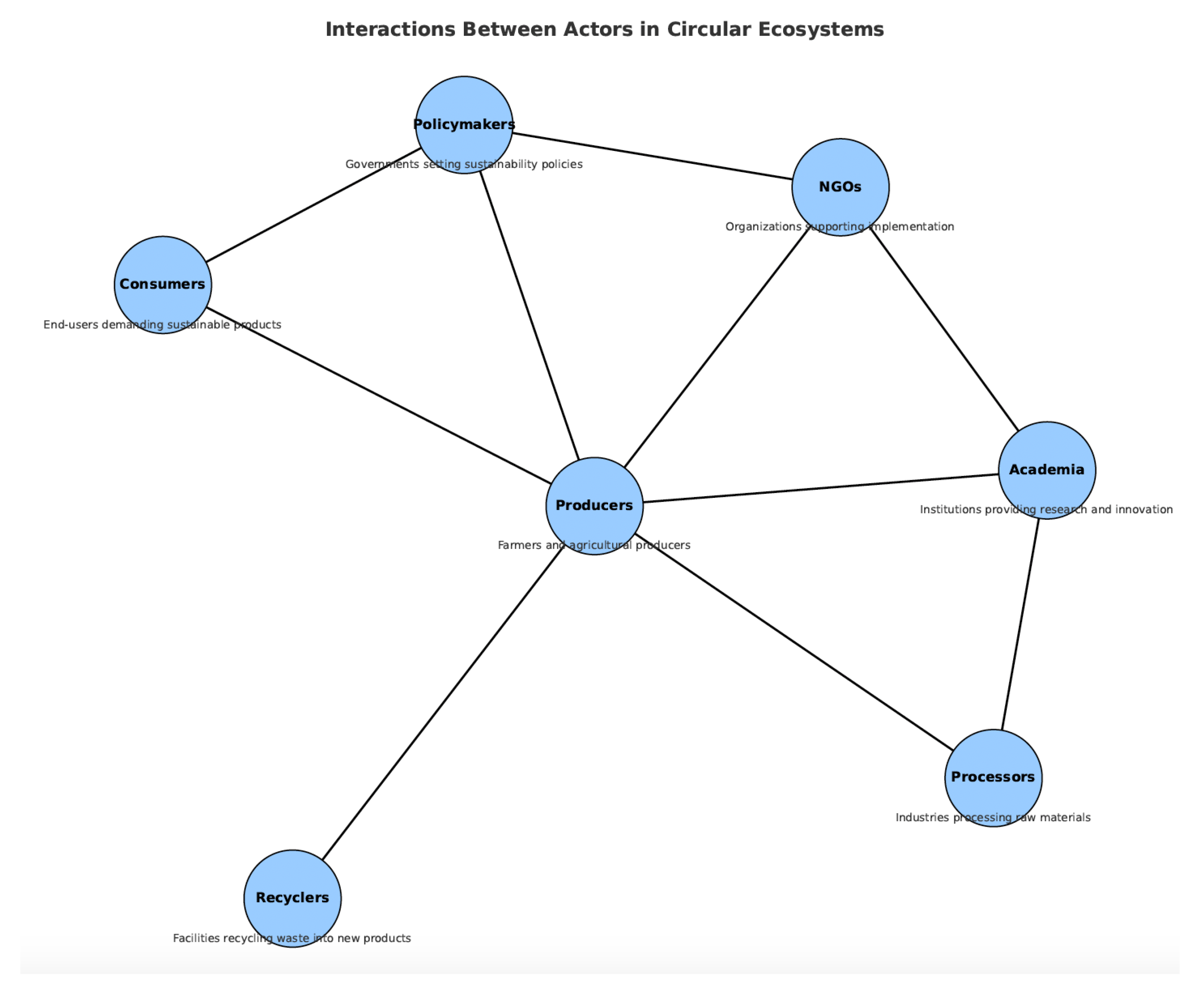

Although not structured as formal case studies, this approach enabled the identification of recurring patterns and analytical insights from localized experiences, thereby reinforcing the territorial and multi-actor perspective of the study. As an output of the interpretive process, a conceptual map of circular interactions was developed (

Figure 2), synthesizing material flows, actor interconnections, and key mechanisms for closing production loops within the analyzed agro-industrial ecosystems.

Internal validity was ensured through the systematic cross-verification of multiple sources of evidence, while external validity was addressed by comparing the findings with documented analogous experiences in Colombia, Brazil, and Mexico. This comparative dimension allowed for an assessment of the transferability of the findings to other rural Latin American contexts.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Business Ecosystem: Genesis and Evolution

The concept of the business ecosystem originates from an analogy with biological ecosystems and was introduced into the field of management by James F. Moore in his influential article “Predators and Prey: A New Ecology of Competition” (1993). Moore argued that firms do not operate in isolation but within dynamic and interdependent networks involving competitors, suppliers, customers, and other key stakeholders. In such systems, innovation and co-evolution play a central role in determining organizational success. Since its introduction, the ecosystem approach has evolved to describe collaborative environments and interconnected relationships among firms as essential conditions for sustaining competitive advantage [

18].

Unlike classical models of organizational analysis, the ecosystem perspective emphasizes adaptability and resilience, shifting the analytical focus away from the individual firm and toward the broader constellation of relationships that sustain it.

In recent years, the business ecosystem concept has been expanded to incorporate sustainability principles, particularly within the framework of the circular economy. In this context, business ecosystems are reconfigured as cooperative systems oriented toward resource regeneration, waste reduction, and the co-creation of environmental and social value [

15].

Empirical evidence from Latin America suggests that these models acquire heightened relevance when adapted to rural contexts characterized by structural and institutional limitations. As Vasseur [

19] notes, business ecosystems in rural Latin American settings must not only pursue economic objectives but also integrate social, cultural, and environmental dimensions. This requires ecosystem models that are responsive to territorial specificities, acknowledging the diversity of natural resources, traditional agricultural practices, and existing community networks.

3.2. Rural Business Ecosystems and Circular Economy Principles

The consolidation of rural business ecosystems takes on particular significance when aligned with the principles of the circular economy. These principles—centered on resource regeneration, waste minimization, and shared value creation—offer an operational framework to reconfigure productive systems in territories experiencing high pressure on natural resources. In such settings, which are often marked by fragmented production structures and limited technological infrastructure, the coordinated participation of stakeholders such as small-scale producers, cooperatives, universities, and non-governmental organizations becomes essential. These actors play a key role in developing business models based on the valorization of by-products, efficient resource use, and the strengthening of territorial value chains [

20].

Nonetheless, the implementation of circular economy principles in rural contexts encounters several structural barriers. These include limited integration with sustainable markets, a low level of technological development in the agricultural sector, and increasing ecological vulnerability.

Various case studies across Latin America illustrate how rural business ecosystems can function as effective platforms for the deployment of circular strategies. In Colombia, for example, the coffee sector has incorporated circular practices through environmental and social certifications, promoting the valorization of organic waste and fostering technical training programs through partnerships between cooperatives such as the

National Federation of Coffee Growers and public institutions like

SENA [

21,

22].

In Ecuador, community-based tourism has emerged as a viable strategy for embedding circular principles into rural economic activities. Initiatives such as the one in San Clemente—developed with support from NGOs and international cooperation programs—have implemented sustainable tourism circuits that combine heritage conservation with organic waste management [

23].

Meanwhile, Mexico has fostered agroecological initiatives that merge traditional knowledge with technological innovation. These efforts have succeeded in closing nutrient cycles, reducing dependency on external inputs, and enhancing the resilience of local productive systems—advancing low-impact circular models [

24].

From these case studies, several common patterns can be identified. These include multi-actor coordination, the presence of anchor institutions (such as cooperatives or local governments), and the gradual scaling of regenerative practices. While these initiatives remain localized, they provide empirical evidence supporting the hypothesis that circular principles can be effectively territorialized—even in settings with limited institutional capacity [

25].

To contextualize the current situation in Latin America regarding the implementation of circular economy principles in the agricultural sector, selected relevant indicators are presented in

Table 1.

These indicators provide a clearer understanding of the regional progress and challenges in advancing circular agriculture, reinforcing the urgent need for collaborative frameworks that integrate public policy, technical capacity, and strategic financing.

From a circular bioeconomy perspective, business ecosystems—including those in rural areas—act as key drivers in the transition toward an economy that prioritizes regeneration and inclusivity. Three core strategies underpin this transition.

The first strategy emphasizes the valorization of waste and by-products by leveraging agricultural, forestry, aquaculture, and livestock biomass to produce new outputs such as bioenergy, bioplastics, and biofertilizers.

The second strategy aims to diversify local economies by fostering bio-based value chains (BVCs), thereby generating rural employment opportunities rooted in renewable biological resources.

The third strategy involves the integration of traditional knowledge with scientific expertise by incorporating ancestral practices with modern innovation in ways that respect the cultural and ecological contexts of each territory. This approach promotes territorial innovation by encouraging the implementation of clean technologies and biotechnological solutions through collaborative models involving universities, local governments, private enterprises, and civil society actors [

26,

27]. Furthermore, it bolsters resilience and sustainability by supporting the responsible use of natural resources, conserving biodiversity, and enhancing climate change adaptation capacities.

The circular bioeconomy has created new spaces for multisectoral collaboration, enabling the formulation of strategies that not only conserve natural capital but also foster robust rural business ecosystems. These ecosystems, in turn, enhance the vitality and global relevance of rural territories.

Furthermore, the circular economy framework provides rural business ecosystems with a strategic foundation for aligning local development with broader goals of sustainability, social equity, and territorial cooperation. Unlike extractive or enclave-based models, this approach promotes the integration of regenerative practices and collaborative arrangements that effectively valorize endogenous resources—natural, cultural, and social—in a manner that is both efficient and resilient.

In Latin America, various studies have documented how the activation of local cooperation networks can mitigate structural barriers associated with inequality, economic dependency, and limited access to basic services. These networks function as catalysts for building local capacities, particularly in rural areas facing high levels of social exclusion [

3,

28,

29,

30].

A compelling empirical example is found in the community of San Clemente, located in the province of Imbabura, Ecuador, where community-based tourism has been consolidated as part of a business ecosystem guided by circular economy principles. In this context, local families have developed a comprehensive offering that integrates lodging services, guided tours, and cultural experiences, drawing upon traditional practices such as ecological agriculture, ancestral medicine, and artisanal production [

31].

Such experiences have not emerged in isolation. The consolidation of this model has been supported by public institutions such as the

Ecuadorian Ministry of Tourism, which has provided support through certifications, technical training, and promotion strategies targeting responsible tourism niches [

32]. This coordination between community actors, government agencies, non-governmental organizations, and family-run enterprises exemplifies territorial symbiosis, wherein the flows of knowledge, services, and resources are mutually reinforcing within a circular framework.

From a results-oriented perspective, recent studies in Latin America have reported significant increases in household income as a result of sustained community tourism initiatives. In the community of Misminay, located in Cusco (Peru), families involved in such initiatives have generated additional weekly income ranging from

$100 to

$400 depending on the type of activity undertaken. These earnings have contributed to improvements in key areas such as education and nutrition [

33].

Similarly, a comparative analysis of experiences in Brazil, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Mexico, and the Dominican Republic indicates that such projects have strengthened local capacities and contributed to the economic development of participating communities [

34].

In the case of San Clemente (Ecuador), local estimates suggest that over 60% of households are directly or indirectly engaged with the tourism ecosystem, either as a primary or complementary economic activity [

31]. This engagement has yielded positive outcomes in terms of improved access to basic services, local economic revitalization, and the strengthening of community cohesion.

While these results cannot be generalized without caution, the case of San Clemente illustrates how circular economy principles can be territorially grounded through collaborative models that integrate identity, sustainability, and economic value. Collectively, these processes reinforce the hypothesis that circular ecosystems, when adapted to rural contexts, can serve as vectors of social innovation and structural transformation.

3.3. Strategic Applications of Circular Principles in Agroindustry

In agroindustrial contexts within emerging economies—such as Ecuador’s coastal region—the principles of bioeconomy and circular economy are increasingly positioned as key tools to address structural challenges related to sustainability, production efficiency, and climate resilience. Among the most salient principles are industrial symbiosis, regenerative design, and the closure of material and energy loops. These frameworks offer a blueprint for the reconfiguration of production systems in accordance with circular logic.

Industrial symbiosis, in its broadest sense, can be defined as the interconnection of productive activities that enables the mutual utilization of energy, material, and by-product flows. In Ecuador’s agri-food sector, this strategy has begun to materialize through the transformation of agri-waste into biofertilizers, biogas, or electricity. For instance, Magri et al. [

35] report that digestate derived from anaerobic digestion contributes to the closure of agricultural nutrient cycles, enhancing soil fertility and reducing reliance on synthetic inputs. Similarly, innovations targeting the production of biodegradable packaging from agricultural waste offer promising solutions for reducing conventional plastic consumption and operational costs [

36].

Regenerative design, in turn, aims to restore and sustain the ecological functionality of agroecosystems. This approach is exemplified by practices such as agroforestry, which integrates native trees into crops like cacao or plantain. This practice has been shown to promote biodiversity, enhance carbon sequestration capacity, and improve soil health [

37]. In Ecuador’s Sierra and coastal regions, a decline in synthetic fertilizer utilization has been documented through the implementation of leguminous crop rotations, as well as the adoption of low-impact technologies such as drip irrigation and rainwater harvesting. These practices have proven effective in bolstering water resilience under heat stress conditions [

38,

39].

Closing material and energy loops constitutes a structural pillar of the circular model. In the plantain production chain, organic residues are converted into compost and biofertilizers that improve soil structure, reduce emissions, and promote more sustainable yields [

40]. Similarly, residual biomass from African palm has begun to be used for on-site steam and electricity generation, thereby reducing dependence on fossil fuels and lowering the carbon footprint. Emerging technologies such as aquaponics—which combine fish farming with plant cultivation through water and nutrient recirculation systems—further exemplify closed-loop production schemes with high resource-use efficiency [

41].

Although these applications are not yet widespread, they provide concrete evidence of the technical feasibility of circular principles in medium-scale and community-based agroindustries. Their adoption is not only a response to increasing environmental pressures, but also a reaction to evolving market dynamics that favor products with verifiable sustainability attributes. Nevertheless, the diffusion of these practices must be analyzed in relation to structural conditions such as access to financing, availability of infrastructure, and the technical capacities of local actors—issues that will be addressed in subsequent sections.

3.4. Latin America: Impacts, Barriers, and Transformative Potential

Circular bioeconomy and circular economy have increasingly been recognized as emerging approaches for addressing the structural challenges faced by resource-intensive sectors such as agroindustry. In theory, these models propose a shift from linear systems—based on extraction and disposal—toward regenerative systems that promote efficient material use, waste valorization, and territorial integration. Their conceptual framework aligns closely with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as outlined by the

Department of Economic Development, Sustainability and Environment [

42] in the

Circular Economy and Bioeconomy Plan 2024 for the Basque Government. These alignments are particularly evident in goals such as: Zero Hunger (SDG 2), Clean Water and Sanitation (SDG 6), Affordable and Clean Energy (SDG 7), Decent Work and Economic Growth (SDG 8), Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure (SDG 9), Responsible Consumption and Production (SDG 12), Climate Action (SDG 13), Poverty Reduction (SDG 1), Life on Land (SDG 15), and Partnerships for the Goals (SDG 17) [

43,

44].

In Ecuador, the agroindustrial sector plays a pivotal role due to its economic weight and direct connection to territorial and natural resources. The incorporation of circular principles into rural production systems has begun to yield partial benefits, including waste reduction, substitution of synthetic inputs, and the rehabilitation of degraded soils [

45]. However, these outcomes are highly dependent on structural conditions that are not always present, particularly in rural zones with limited institutional capacity.

At the regional level, multiple barriers hinder the scaling-up of circular models. One of the most persistent is the lack of infrastructure for the collection, sorting, and transformation of organic waste. In Ecuador, for instance, it is estimated that over 95% of solid waste ends up in landfills, despite a significant share being composed of potentially recoverable organic matter [

46].

Additionally, a lack of awareness and limited technical knowledge regarding the potential of circular economy models restricts adoption, particularly among small- and medium-scale producers. Traditional practices—such as open burning of waste or the intensive use of agrochemicals—continue to prevail, even in areas where regenerative approaches have been promoted [

47]. Another critical barrier is unequal access to financing. Key technologies such as biodigesters, industrial composting systems, or biofiltration units require initial capital investments that many rural cooperatives are unable to afford. While green credit lines and multilateral incentives do exist, they tend to be concentrated in urban or large-scale projects, thereby excluding small or informal production units [

48].

The aforementioned limitations are further compounded by the presence of institutional fragility. Fragmented regulatory frameworks, the absence of specific fiscal incentives, and insufficient local technical capacity to support the implementation of circular solutions all hinder progress [

49]. These deficiencies impede the capacity of subnational governments to facilitate productive transitions and attenuate the impact of sectoral innovation endeavors.

Despite these challenges, several factors underpin the region’s latent potential for transformative change. These include its rich biological diversity, a deep well of traditional agricultural knowledge, and a growing ecosystem of cooperatives, producer associations, and grassroots organizations engaged in sustainable innovation. In this context, the circular economy could function as a catalyst for technological, social, and institutional transformations. However, realizing this potential requires the implementation of inclusive governance frameworks and the creation of accessible financial mechanisms that prioritize support for the most vulnerable actors.

Figure 3 summarizes the main obstacles faced by rural territories in implementing circular economy and bioeconomy models, the enabling conditions required to overcome them, and the key actors responsible for driving this transition.

3.5. The Productive Transition in Latin America: Opportunities, Limitations, and Scenarios

In Latin America, the

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) highlights that the bioeconomy has gained prominence as a reference framework for implementing innovative policies for the sustainable use of natural resources. In Ecuador, for instance, the relevance of the multicomponent biorefinery model (circular bioeconomy) has been underscored for advancing a high value-added bioeconomy, leveraging various types of biomass—including residual biomass. At the same time, opportunities have been identified for scaling up innovative advanced bioeconomy initiatives that contribute to inclusive and sustainable productive development [

9].

Moreover, the circular economy has emerged as a prominent conceptual framework for reorienting the productive transformation of agroindustrial sectors traditionally rooted in extractive models. The integration of sustainability and efficiency criteria in agricultural systems has positioned by-product valorization as increasingly strategic. This transition is driven by mounting environmental pressures and the evolution of global markets, which increasingly demand goods with certified provenance and a reduced ecological footprint.

According to ECLAC, average economic growth in 2024 was 2.1%, though structural limitations persist, including low levels of productive investment, weak diversification, and insufficient innovation [

3]. In this context, multilateral organizations such as the

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have emphasized that the efficient utilization of agro-industrial waste—when integrated within circular economy frameworks—can serve as a vector of productive transformation [

1]. Market projections reinforce this view. For instance, the micronutrient fertilizer sector in Latin America, valued at USD 485.78 million in 2023, is expected to grow at an annual rate of 3.9% through 2032. Similarly, the global agricultural adjuvants market anticipates an annual expansion of 5.4% [

50]. Although country-specific data remain limited, these trends reflect a growing interest in technologies that enhance resource efficiency and reduce waste.

From a material standpoint, the region enjoys a strategic advantage due to its biological wealth and large volumes of residual agro-industrial biomass, including by-products from plantain, cacao, and African palm. It has been demonstrated that countries such as Ecuador, Colombia, and Brazil possess the capacity to transform these residues into biofertilizers, bioplastics, biogas, or compostable materials. When such solutions are combined with regenerative practices—such as agroforestry, crop rotation, or efficient irrigation—they open up possibilities for redefining production models toward low-impact, territorially resilient systems [

51,

52].

Concurrently, the mounting global demand for organic, sustainable, and fair trade-certified products offers substantial opportunities for strategic repositioning of Latin America’s agroindustry. In Ecuador, for instance, the export of cacao husk derivatives to the cosmetics industry has facilitated income diversification and value creation at the origin [

51].

At the institutional level, several countries have initiated the development of policy frameworks designed to facilitate this transition. In Colombia, the

National Circular Economy Strategy functions as a roadmap for formalizing circular practices and incentivizing sustainable value chains [

52]. Initiatives spearheaded by the

Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in countries such as Ecuador and Peru have furnished financing, technical assistance, and regulatory support to pilot projects in biorefineries, bioenergy, and agricultural recycling.

However, this transition is not without constraints. Infrastructure for waste treatment and recovery remains deficient in many rural areas. In Ecuador, for instance, significant agricultural regions are devoid of composting facilities, biodigesters, or collection centers, resulting in augmented logistics expenditures and impediments to the expansion of circular solutions [

53].

Additionally, the upfront investment required to implement technologies such as biodigesters, sensors, or smart irrigation systems remains a barrier for many cooperatives and small agroindustrial enterprises. This limitation is compounded by weak alignment among regulatory frameworks, limited availability of incentives, and unequal access to green financing mechanisms.

Beyond material conditions, the productive transition also demands a shift in managerial logic. This includes cultivating an organizational culture oriented toward sustainability, building local capacity, and consolidating collaborative networks among producers, technicians, institutions, and consumers. In this regard, initiatives led by social enterprises, universities, and local governments have demonstrated that circular economy principles can be adapted through cooperative and territorial models—yielding positive impacts in employment, innovation, and resilience [

54,

55].

Digital tools—such as soil sensors, smart irrigation systems, mobile apps for waste management, and traceability platforms—are increasingly being integrated into these dynamics as cross-cutting technological enablers. When coupled with inclusive policy design and strong territorial governance structures, these tools can significantly enhance the prospects for an effective transition toward regenerative agroindustrial development [

56].

Figure 4 presents a comparative overview of these opportunities and limitations, summarizing five key dimensions that influence the adoption of circular practices in Latin American agroindustry.

3.6. Feasibility, Limits, and Contributions of Circular Ecosystems in Ecuadorian Agroindustry

Circular ecosystems applied to Ecuador’s coastal agroindustrial sector are emerging as a promising alternative to linear production models, particularly due to their capacity to integrate local actors into collaborative processes focused on resource regeneration. Through the valorization of agricultural by-products such as plantain peels, cacao residues, and African palm waste, various experiences have been identified that move toward closed-loop systems, with documented economic, ecological, and social benefits [

57,

58,

59].

In these cases, materials previously treated as waste are being transformed into biofertilizers, biofuels, bioplastics, or nutraceutical inputs. These transformations contribute to income diversification in rural areas, reduce dependency on imported inputs, and improve soil health indicators. However, these advances remain confined to isolated initiatives, and their scaling is contingent on structural factors that require thorough analysis.

Among the main technological and economic constraints, high processing costs associated with biomass conversion stand out, as well as the lack of specialized infrastructure in rural areas. Technologies such as biodigesters or composting facilities require initial investments and technical maintenance beyond the capacity of many small and medium-sized production units. This challenge has been widely cited as a key barrier to large-scale adoption of circular practices [

60,

61].

In addition to material limitations, cultural and educational factors also influence the low adoption rate of circular approaches. The persistence of conventional agricultural practices and limited familiarity with regenerative principles hinder the implementation of sustainable solutions. According to Gorgolewski [

62], these gaps can be mitigated through context-sensitive technical training programs that incorporate local knowledge and promote gradual appropriation of new technologies.

From a comparative perspective, Ecuador possesses a structural advantage: an abundance of residual biomass from agro-export sectors such as banana, cacao, and African palm. These residues, in addition to having potential value in national and international markets, can significantly reduce the ecological footprint of production chains when managed within circular frameworks. This resource availability, combined with growing global demand for sustainable products, positions Ecuador as a potential reference case within the Andean region for regenerative production innovation [

63].

The role of public policy and international cooperation has been critical in fostering enabling environments for sustainable innovation. Initiatives such as the National Circular Economy Plan and multilateral financing programs have begun to provide incentives, technical training, and credit access for territory-based circular projects. However, their scope remains limited due to weak interinstitutional coordination and the absence of an integrated vision linking agricultural, industrial, environmental, and technological policies.

In this scenario, agricultural digitalization emerges as a cross-cutting axis with the potential to reshape structural conditions in the sector. Tools such as traceability platforms, agricultural sensors, waste management systems, and environmental monitoring technologies are being introduced into productive contexts, albeit with early-stage results. Their implementation enables more efficient resource use, reduces information asymmetries, and strengthens connections between rural producers and sustainable markets [

64].

In summary, the feasibility of circular ecosystems in Ecuadorian agroindustry does not rely solely on their technical justification, but rather on a constellation of enabling conditions involving intersectoral coordination, public and private investment, localized capacity building, and institutional strengthening. These factors define the parameters within which circular models can be consolidated as structural strategies for a sustainable productive transition.

3.7. Structural Impacts on Sustainability, Resilience, and Rural Innovation

The adoption of circular approaches in Ecuadorian agroindustry has begun to generate transformations that go beyond the technical-productive dimension, shaping structural processes with far-reaching environmental, economic, and social implications. These impacts do not occur automatically; rather, they rely on the effective articulation of technological solutions, territorial knowledge, and adaptive governance frameworks.

Empirical data reveal a 45% to 55% reduction in solid waste and up to an 18% increase in agricultural productivity following the implementation of circular models, particularly in banana and coffee value chains. These quantifiable results validate the economic and environmental potential of the circular economy in rural contexts.

From an environmental standpoint, technologies such as anaerobic digestion enable the valorization of organic residues from intensive crops—such as African palm, banana, and cacao—into clean energy (biogas), thereby reducing reliance on fossil fuels and lowering greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, the use of digestate as an organic amendment has improved key soil quality parameters, including water retention, fertility, and microbiological biodiversity, in regions experiencing soil degradation [

65,

66].

From an economic perspective, the valorization of co-products opens new pathways for productive integration. Previously discarded residues—such as peels, fibers, and plant pulps—are being transformed into inputs for biofertilizer production, nutraceuticals, and bioplastics. This productive diversification not only generates new income streams but also reduces dependence on imported inputs and enhances the autonomy of rural production units in the face of international agricultural market volatility [

67].

At the social and territorial level, the implementation of circular models stimulates the dynamism of local economies by creating demand for both skilled and unskilled labor in waste transformation and commercialization. This process, documented in cases such as Manabí and the Inter-Andean Highlands, has been particularly effective in promoting the inclusion of rural women and youth in formalized productive activities—challenging historically entrenched patterns of labor informality [

22].

Moreover, the relocalization of value-added—that is, transforming residues at their point of origin rather than in distant industrial centers—strengthens linkages between production systems and traditional knowledge. This synergy is critical in regions with a strong agroecological identity, where technological solutions have been co-designed based on cultural practices and pre-existing community networks.

Despite these advancements, a latent risk persists: the generalized assumption that all circular practices inherently lead to improvements in sustainability. This presumption, often found in parts of the literature, can obscure underlying design, implementation, or governance failures. As Le [

67] warns, the net impacts of circular initiatives—whether environmental, economic, or social—must be rigorously assessed, taking into account the institutional and productive contexts in which they are embedded.

In the Ecuadorian case, marked by high territorial heterogeneity and uneven institutional capacities, the effectiveness of circular ecosystems will depend on their ability to adapt to local conditions rather than replicating decontextualized technocratic models. Therefore, rather than promoting specific technologies, an approach is required that prioritizes territorial learning, the social appropriation of innovation, and collaborative governance as foundational pillars to sustain long-term impacts.

Quantitative results from various circular economy initiatives in agroindustrial sectors of Ecuador and Colombia demonstrate the transformative potential of these practices in terms of sustainability and efficiency. As shown in

Table 2, the implemented projects have achieved significant reductions in waste generation, increases in agricultural productivity, and considerable biogas production from the utilization of organic by-products. These data reinforce the technical and economic viability of circular models in rural Latin American contexts.

3.8. Innovation, Collaboration, and Scalability in the Implementation of Circular Models

The transition toward circular models in Ecuadorian agroindustry must be understood as a systemic process that integrates technology, socio-territorial relations, and governance. In this context, innovation assumes a relational character, wherein universities, local communities, governments, NGOs, and multilateral organizations co-construct solutions tailored to specific rural conditions [

68].

Applied research has played a pivotal role in this process. Universities and technological institutes have developed appropriate technologies—such as modular biodigesters, soil sensors, and agro-environmental monitoring systems—which have reduced reliance on imported solutions and strengthened local technical capacities.

Likewise, international cooperation has enhanced territorial innovation ecosystems. Initiatives led by the

German Technical Cooperation (GIZ) in provinces such as Manabí, Santa Elena, and Guayas have supported the installation of community composting facilities and agricultural recycling systems, yielding positive outcomes in terms of sustainability and economic inclusion [

28].

Cases such as San Clemente or the Chocó Andino illustrate the feasibility of integrating contemporary technologies with traditional agroecological practices. These experiences underscore the importance of local innovation networks and collaborative learning in generating viable socio-technical solutions.

The incorporation of digital technologies—traceability platforms, smart water sensors, and mobile waste management applications—has improved operational efficiency, reduced losses, and facilitated access to sustainability-driven markets. However, scalability remains constrained by structural limitations. Many initiatives still depend on external funding and lack institutional frameworks for long-term consolidation.

Citing again the Kalundborg industrial symbiosis model (Denmark), frequently referenced in circular economy literature, useful principles such as inter-sectoral flow exchange and public–private collaboration can be identified [

16,

69]. Nevertheless, its direct application in Latin America is limited by differences in institutional capacity, business culture, and territorial planning [

45,

70]. Its value lies less in replication and more in inspiring context-specific adaptations—such as the integration of agroindustry, fisheries, and tourism in Ecuador’s coastal regions.

The literature consistently emphasizes that circular innovation depends on knowledge networks, trust among actors, and adaptive territorial governance structures [

71,

72,

73]. In countries such as Brazil and Colombia, the most sustainable progress has occurred in contexts where multi-level coordination and intermediary nodes facilitate implementation [

74]. In Ecuador, the absence of stable platforms for territorial governance constrains scalability.

To consolidate these models, fiscal incentives, coherent regulatory frameworks, and participatory mechanisms that engage all ecosystem actors are required. It is essential to recognize that circular economy models are not universally transferable. Their implementation must emerge from adaptive co-design processes, grounded in institutional capacity, productive diversity, and socio-territorial conditions. Without these elements, initiatives risk becoming fragmented or structurally unviable.

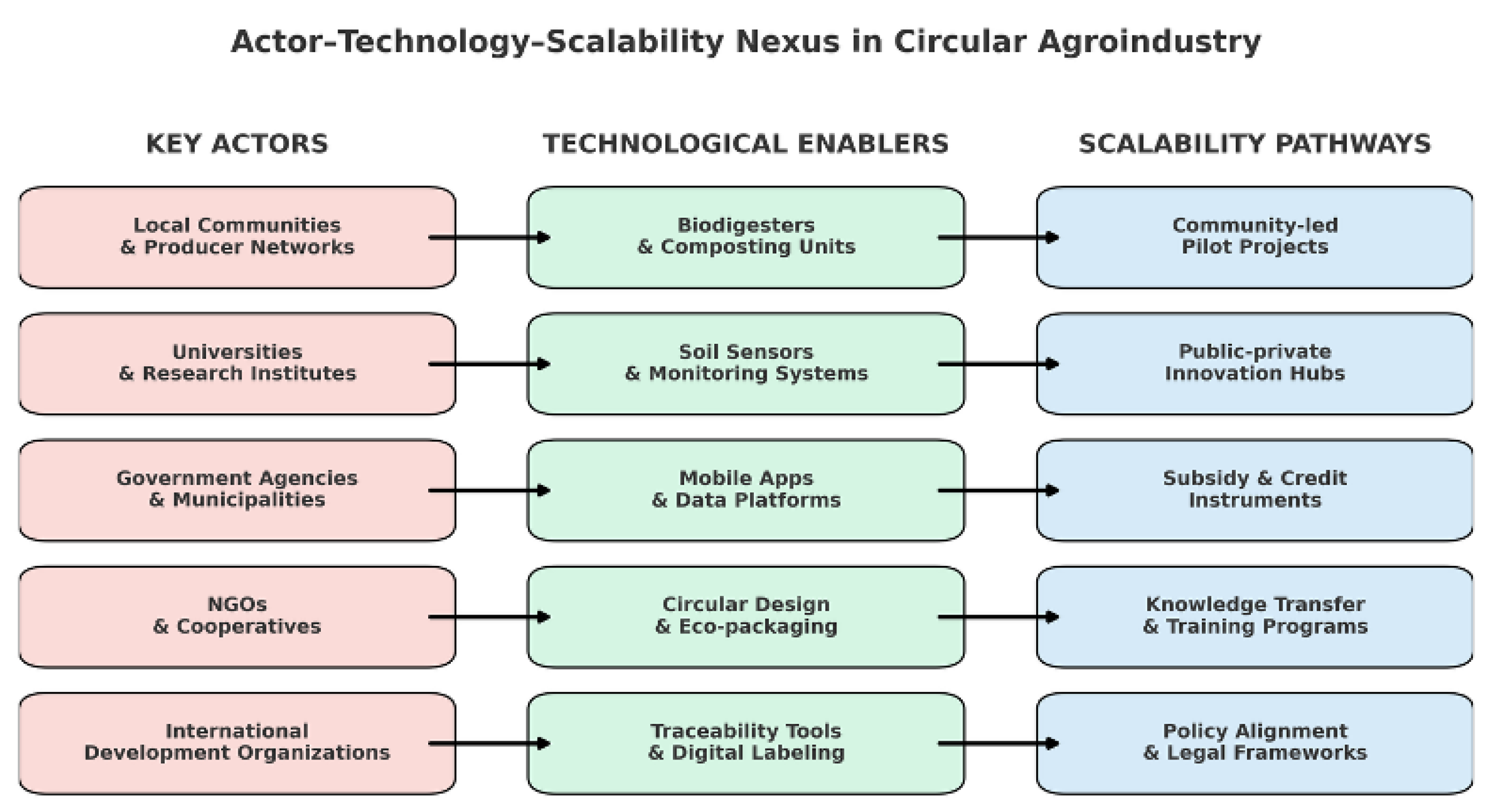

Figure 5.

Systemic linkages between actors, circular technologies, and enablers of scalability. This infographic visualizes the dynamic articulation among key actors (such as universities, NGOs, and local producers), circular economy technologies, and critical enabling conditions for the scalability of circular models in rural agroindustry. The model highlights the need for multilevel coordination, context-sensitive technological adoption, and institutional support for sustainable transition.

Figure 5.

Systemic linkages between actors, circular technologies, and enablers of scalability. This infographic visualizes the dynamic articulation among key actors (such as universities, NGOs, and local producers), circular economy technologies, and critical enabling conditions for the scalability of circular models in rural agroindustry. The model highlights the need for multilevel coordination, context-sensitive technological adoption, and institutional support for sustainable transition.

4. Conclusions

This study has explored the feasibility, challenges, and opportunities associated with integrating circular economy and circular bioeconomy principles into Ecuador’s coastal agroindustrial sector, with a particular focus on the banana, cacao, and African palm value chains. Through a systematic literature review and a contextualized analysis of case studies, the research identified key patterns underlying the emergence of rural circular ecosystems as sustainable strategies for territorial transformation.

The findings underscore that principles such as industrial symbiosis, regenerative design, and closed-loop systems offer significant potential to transition toward more resilient, inclusive, and environmentally sustainable production models. However, these transformations are neither automatic nor evenly distributed. Their success depends on the presence of critical enabling conditions, including adequate infrastructure, accessible financing, inter-institutional coordination, and the development of local capacities. Technological innovation, while essential, is insufficient if not embedded in socio-institutional contexts that ensure its appropriation and long-term viability.

Methodologically, this study contributes by bridging the conceptual frameworks of business ecosystems and territorial circular economy. This integrated perspective allows for the reconceptualization of productive transition not merely as a technical shift, but as a systemic transformation embedded in local social and territorial dynamics. Empirically, the research provides valuable evidence from Ecuadorian initiatives, emphasizing their adaptive, multi-actor nature and their potential to generate added value at the origin.

Nonetheless, limitations remain. The absence of harmonized regional datasets complicates the accurate estimation of environmental and economic impacts, while the exploratory nature of the case analysis restricts the generalizability of findings. Future research should aim to assess net sustainability outcomes, conduct comparative analyses across agroindustrial chains, and identify the institutional drivers and barriers shaping success or failure.

Although still at an incipient stage, circular and bio-circular economy initiatives in Ecuador’s coastal agroindustry show promising signs of structural consolidation. In light of pressing global challenges—ranging from biodiversity loss and climate change to ecosystem degradation and waste accumulation—these models emerge as both viable and necessary alternatives. Their transformative potential, however, will ultimately depend on the capacity of public institutions, civil society, and productive actors to co-create a development pathway that integrates ecological efficiency, social equity, and territorial competitiveness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C.; Validation, R.C., E.S., L.T., L.V., F.V.; Investigation, R.C., E.S., L.V.; Writing—original draft preparation, R.C.; Writing—review and editing, R.C., E.S., L.T., L.V., L.R., F.V.; Supervision, R.C., E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study are available within the article and its referenced sources. No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the authorities of Universidad Estatal Península de Santa Elena (UPSE).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation |

Full Name |

| FAO |

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| IPCC |

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| ECLAC |

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (CEPAL) |

| INEC |

National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (Ecuador) |

| GIZ |

German Agency for International Cooperation (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit) |

| IDB |

Inter-American Development Bank (Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo) |

| UNEP |

United Nations Environment Programme |

| SDGs |

Sustainable Development Goals (Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible) |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| WoS |

Web of Science |

| IICA |

Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture |

| NGO |

Non-Governmental Organization |

| PRISMA |

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2023, 2023. Accessed from http://www.fao.org.

- on Climate Change (IPCC), I.P. Synthesis Report of the IPCC Sixth Assessment, 2023. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr.

- ECLAC. Climate Change in Latin America: Economic Outlook, 2023.

- Kada, R. Environmental Risks in Agro-export Chains. Revista de Economía Rural 2012, 15, 101–117.

- Saad, L. Waste and Resource Use in Ecuador’s Cocoa Industry. Journal of Agrifood Systems 2021, 22, 145–159.

- Ponce, J.; Álvarez Barreto, S.; Almeida, P. Bioeconomía y sostenibilidad en la agroindustria ecuatoriana. Revista Latinoamericana de Economía Circular 2021, 4, 88–103.

- Luciano, A.; Torres, M.; Vega, D. Agrochemical Contamination and Soil Biodiversity Loss in Banana Plantations. Environmental Science and Policy 2024, 145, 45–58.

- Xu, L.; Zhang, W.; Ortega, A. Waste Governance and Agricultural Policy Reform in Ecuador. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 370, 133239.

- Orejuela-Escobar, L.M.; Rodríguez, A.G. Bioeconomía para la diversificación productiva y la agregación de valor: Biorrefinerías de residuos en cadenas agroindustriales en el Ecuador; Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL), 2024.

- Gutiérrez-Correa, M. Bioeconomía: Primera parte. Revista Peruana de Biotecnología 2008, 1, 1–10.

- Parra, M.; Pérez, J. Economía circular y modelos de negocio sostenibles: Una revisión de la literatura. Revista de Estudios Empresariales 2020, 2, 45–60.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INEC). Gestión de residuos sólidos 2022, 2022.

- Rodale Institute. Regenerative Agriculture and the Soil Carbon Solution, 2014.

- CO2balance. Regenerative Agriculture: The Next Great Carbon Frontier?, 2022.

- Santagata, R.; Zucaro, A.; Viglia, S.; Ripa, M.; Tian, X.; Ulgiati, S. Assessing the sustainability of urban eco-systems through Emergy-based circular economy indicators. Ecological Indicators 2020, 109, 105859. [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, N.B. Industrial symbiosis in Kalundborg, Denmark: A quantitative assessment of economic and environmental aspects. Journal of Industrial Ecology 2006, 10, 239–255. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; et al.. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, P.; van Nes, E.H.; Scheffer, M. Neutral competition boosts cycles and chaos in simulated food webs. Royal Society Open Science 2020, 7, 191532. [CrossRef]

- Vasseur, L. How ecosystem-based adaptation to climate change can help coastal communities through a participatory approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2344. [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Monroy, L.; Potts, S.G.; Tzanopoulos, J. Drivers influencing farmer decisions for adopting organic or conventional coffee management practices. Food Policy 2016, 58, 49–61. [CrossRef]

- Rueda, X.; Lambin, E.F. Responding to globalization: Impacts of certification on Colombian small-scale coffee growers. Ecology and Society 2013, 18, 21. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, H.E.P.; de Andrade, S.A.L.; Santos, R.H.S.; Baptistella, J.L.C.; Mazzafera, P. Agronomic practices toward coffee sustainability: A review. Scientia Agricola 2024, 81, e20220277. [CrossRef]

- Lomas, K.R.; Trujillo, C.A. Environmental educational model for community tourism of Fakcha Llaka community-Ecuador. International Journal of Professional Business Review 2018, 3, 95–110. [CrossRef]

- Sosa, M.; Aulet, S.; Mundet, L. Community-based tourism through food: A proposal of sustainable tourism indicators for isolated and rural destinations in Mexico. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6693. [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, F.; Martin, J.; De Luca, C.; Tondelli, S.; Gómez-García-Bermejo, J.; Casanova, E.Z. Computational methods and rural cultural & natural heritage: A review. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2021, 49, 250–259.

- Rodriguez, A.G.; Rodrigues, M.; Sotomayor, O. Hacia una Bioeconomía sostenible en América Latina y el Caribe: elementos para una visión regional. Technical Report 191, Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL), Santiago, 2019. (LC/TS.2019/25).

- Nguyen, T.H.; Wang, X.; Utomo, D.; Gage, E.; Xu, B. Circular bioeconomy and sustainable food systems: What are the possible mechanism? Cleaner and Circular Bioeconomy 2025, 11, 100145. [CrossRef]

- GIZ. Fondo Regional para la Cooperación Triangular en América Latina y el Caribe, 2024.

- Internet Society. Redes comunitarias en América Latina: Desafíos, regulaciones y oportunidades, 2018.

- IICA. Conectividad rural en América Latina y el Caribe, 2021.

- Terán, M. El turismo comunitario y su aporte al desarrollo de la comunidad de San Clemente. Tesis de maestría, Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, 2020. Repositorio UASB.

- Ministerio de Turismo del Ecuador. Emisión de certificado de registro de turismo por primera vez para centros turísticos comunitarios persona jurídica, n.d.

- Gil Arroyo, C.; Barbieri, C.; Sotomayor, S.; Knollenberg, W. Cultivating women’s empowerment through agritourism: Evidence from Andean communities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3058. [CrossRef]

- González, M.; Pérez, L.; Rodríguez, A. Turismo comunitario en Latinoamérica. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research 2024, 6, 45–60.

- Magri, A.; Gallo, A.; Cacho, J. Valorization of agro-industrial residues through anaerobic digestion: A circular economy perspective. Waste Management & Research 2018, 36, 914–921. [CrossRef]

- Vardanega, R. Biodegradable packaging from agro-residues: Innovation in sustainable materials. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2015, 132, 42678. [CrossRef]

- Francaviglia, R.; Almagro, M.; Vicente-Vicente, J.L. Conservation agriculture and soil organic carbon: Principles, processes, practices and policy options. Soil Systems 2023, 7, 17. [CrossRef]

- Imra, M.F.; Rahman, M.; Islam, M. Water-saving technologies for climate-resilient agriculture: A review. Environmental Challenges 2022, 9, 100625. [CrossRef]

- Basche, A.D.; Edelson, O.F. Improving water resilience with more perennially based agriculture. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 2017, 41, 799–824. [CrossRef]

- Ponce, G.; Villacís, J.; Yánez, E. Estrategias de aprovechamiento de residuos agroindustriales para la sostenibilidad en Ecuador. Revista de Desarrollo Rural y Agricultura Sostenible 2020, 41, 112–124.

- Goddek, S.; Delaide, B.; Mankasingh, U.; et al. Challenges of sustainable and commercial aquaponics. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4199–4224. [CrossRef]

- Diakosavvas, D.; Frézal, C. Bio-economy and the sustainability of the agriculture and food system: Opportunities and policy challenges, 2019.

- Rojas-Serrano, F.; Garcia-Garcia, G. Sustainability, circular economy and bioeconomy: A conceptual review and integration into the notion of sustainable circular bioeconomy, 2024. Preprint or forthcoming.

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Circular economy and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: A review of the linkages, 2021.

- Barros, M.V.; Martínez, R.; Vega, L. Circular economy in the agri-food sector: Perspectives for Latin America. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 416, 137838. [CrossRef]

- Cando, C.; Salazar, D.; Muñoz, J. Estadística de información ambiental económica en gobiernos autónomos descentralizados municipales; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos: Quito, 2021.

- Gunawardhana, C. Barriers to the adoption of regenerative agriculture: A Latin American perspective. Environmental Sustainability 2023, 26, 101–110. [CrossRef]

- Rizos, V.; Behrens, A.; Van der Gaast, W.; Hofman, E.; Ioannou, A.; Kafyeke, T.; Flamos, A.; Rinaldi, R.; Papadelis, S.; Hirschnitz-Garbers, M.; et al. Implementation of circular economy business models by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): Barriers and enablers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1212. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, R.; López, C. Políticas públicas y economía circular en América Latina: Avances, brechas y desafíos institucionales. Technical report, Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL), Santiago de Chile, 2020.

- IMARC Group. Agricultural adjuvants market: Global industry trends, share, size, growth, opportunity, and forecast 2023–2032, 2023.

- Raynolds, L.T. Re-embedding global agriculture: The international organic and fair trade movements. Agriculture and Human Values 2000, 17, 297–309. [CrossRef]

- Soto-Ríos, M.; Pineda, G.; Valencia, J. Políticas nacionales para la economía circular en América Latina: Avances y desafíos. Revista Desarrollo Sostenible en la Región Andina 2023, 5, 45–62.

- Morasae, M.; Torres, R.; Mera, L. Infraestructura verde y valorización de residuos agrícolas en zonas rurales del Ecuador. Revista Iberoamericana de Desarrollo Rural 2024, 20, 33–52.

- Corporación 3D. Guía de cultura organizacional para la sostenibilidad empresarial; C3D: Quito, 2020.

- Stahel, W.R. The Circular Economy: A User’s Guide; Routledge, 2019.

- Dinesh, D. Agricultural technologies for climate change adaptation in Latin America: An evidence-based review. Technical report, CCAFS, 2016.

- Pereyra-Camacho, R. Economía circular y agroindustria ecuatoriana: estudios de caso en Esmeraldas y Los Ríos, 2024.

- Sánchez, D.; Muñoz, L.; Torres, A. Valorización de residuos agroindustriales para la producción de biofertilizantes en la región Litoral. Ciencia y Tecnología Agroindustrial 2023, 24, 122–138.

- Ultran, D.; Barreto, M.; Carrillo, K. Bioplásticos a partir de residuos de cacao: Innovación sostenible en la agroindustria ecuatoriana. Revista de Ciencias Ambientales 2023, 41, 35–50.

- Gallego, J.; Reyes, M.; Viteri, F. Tecnologías circulares en la transformación del agro ecuatoriano. Revista de Innovación Productiva 2024, 18, 44–63.

- Sommer, F. Scaling up circular economy innovations in developing countries. Technical report, German Development Institute, 2017.

- Gorgolewski, M. Resource Salvation: The Architecture of Reuse; Wiley-Blackwell, 2017.

- Pardo Cuervo, O.H.; Rosas, C.A.; Romanelli, G.P. Valorization of residual lignocellulosic biomass in South America: A review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2024, 31, 44575–44607. [CrossRef]

- Antikainen, R.; Dalhammar, C.; Hildén, M.; Judl, J.; Jääskeläinen, T.; Kautto, P.; Koskela, S. Circular economy business models in the bio-based sector: Implications for sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 201, 988–1000. [CrossRef]

- Acosta Ortiz, N. Anaerobic digestion of cocoa waste within a circular economy context. Tesis doctoral, Ghent University, 2019.

- Sharma, B.; Vaish, B.; Monika.; Singh, U.K.; Singh, P.; Singh, R.P. Recycling of organic wastes in agriculture: An environmental perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research 2019, 13, 409–429. [CrossRef]

- Le, K.M. Land use restrictions, misallocation in agriculture, and aggregate productivity in Vietnam. Journal of Development Economics 2020, 145, 102465. [CrossRef]

- Silva-Alvarado, E.; Diéguez-Santana, G.; Rodríguez-Rudi, D.; Ruiz-Moreno, J. Prospective of the circular economy in a banana agri-food chain. TEC Empresarial 2023, 17, 34–52. [CrossRef]

- Chertow, M.R. Uncovering Industrial Symbiosis. Journal of Industrial Ecology 2007, 11, 11–30. [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, V.; Contreras, A.; Arriagada, C. Circular Economy and Institutional Weakness in Latin America. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1539.

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy – A new sustainability paradigm? Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 143, 757–768. [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M. The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths; Penguin, 2018.

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2018, 127, 221–232. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, J.L.; et al. Ecosistemas empresariales rurales y desarrollo territorial en América Latina. Revista Latinoamericana de Desarrollo Local 2021, 8, 45–68.

| 1 |

The Kalundborg model (Denmark) is widely recognized as the first and most emblematic case of industrial symbiosis worldwide;emerging spontaneously during the 1960s and 1970s, it consists of a collaborative network of companies that exchange energy, water, and by-products to optimize resource use and minimize waste. Key stakeholders include a coal-fired power plant, an oil refinery, a gypsum board facility, and the local municipality. This industrial ecosystem has demonstrated that economic competitiveness can be effectively combined with environmental sustainability through intersectoral cooperation and the efficient management of resources. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).