Submitted:

12 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cyber Events Database: University of Maryland NIS360 [7,8]

- Actor Type: The actor type is a critical factor in distinguishing the perpetrators of cyberattacks. These perpetrators include criminal organizations, nation-state actors, terrorist groups, hacktivists, and hobbyists. This categorization facilitates the discernment of potential motives and methods employed by the actors in question by cybersecurity researchers and policymakers.

- Motive: The motivation behind each cyberattack is a critical factor in its classification. The motives can be categorized into four distinct groups: economic gain, espionage, protest, and sabotage. The utilization of this categorization facilitates the identification of potential trends and patterns that may emerge in future analyses, thereby providing a framework for anticipating future outcomes.

- Mixed: Cyber incidents are classified into three categories: disruptive, exploitative, or mixed. This categorization facilitates comprehension of the repercussions that cyberattacks have on various organizational systems and the consequences that ensue from these events.

2.2. A Profile of Actor Types in Cyber Threats

- Cybercriminals are individuals or associations of individuals who commit illegal acts in cyberspace with the primary objective of financial gain. These actors leverage vulnerabilities to compromise the security of systems, with the aim of perpetrating financial fraud, stealing the identity of their victims, and obtaining sensitive personal data or confidential information [9,10,11]. A marked increase in cyber activity has been observed, accompanied by the implementation of advanced methodologies involving ransomware and phishing attacks [10,11].

- Actors operating under the auspices of a state entity, either directly or indirectly, seek to gather intelligence for the purpose of espionage and to inflict a blow against other state entities [12,13]. Furthermore, these actors frequently pursue acts of sabotage against critical infrastructure and surveillance systems in matters of geopolitical concern [14,15]. The primary objective of the aforementioned actions is to diminish national security and to acquire a technological superiority over states that are antagonistic towards them.

- Terrorist groups are non-state entities that seek to alter political situations through the instigation of fear. These actors leverage cyberspace to launch attacks against various institutions and beyond. The tactics employed by these actors pose a significant threat to national security and the prestige of the state entity in question. These threats manifest through attacks on critical information systems or infrastructure, which can severely compromise the entity's ability to function effectively [16,17]. The subjects' objectives are driven by a specific ideological framework that guides their actions. These actions are intended to instill fear, modify political circumstances, and, in general, radicalize protest movements.

- Hacktivists who adhere to political or social criteria employ cyberattacks as a medium to articulate their protest against situations that they deem to be in violation of their sense of justice. The objective of these actors is to create problems in the operations of organizations or state entities, thereby promoting their message in specific situations [18,19]. The objective of cyberattacks is twofold: to exploit and to disrupt various services.

- Hobbyists are individuals who engage in activities for the sake of personal interest and enjoyment, often driven by a desire to satisfy their curiosity and receive acknowledgment for their pursuits. While their actions in cyberspace are not inherently malicious, they may unintentionally engage in practices that compromise cybersecurity [20,21]. While not necessarily driven by the same motivations as cybercriminals, the actions of these entities can potentially result in the exploitation of vulnerabilities or service disruption.

2.3. Motives Underlying Cyber Events

- Financial Gain: The primary motivation for cybercriminals is typically economic gain. This is achieved through data breach or data theft attacks, or ransomware [22,23]. These actors employ sophisticated methods to exploit vulnerabilities, guided by the pursuit of optimal economic gain [24]. Cyberattacks driven by economic gain can be categorized as exploitative in nature, as they focus on targeting data that is being utilized for economic gain.

- Espionage: Espionage is the prevailing motive for state entities, with the objective being the collection of information and the procurement of classified data, ultimately leading to the attainment of a strategic advantage [25,26]. The phenomenon under consideration combines both disruptive and exploitative cyber events.

- Protest: The impetus behind the various activists seeking the shutdown of online services is protest, which is motivated by socio-political reasons [27,28]. These actors typically engage in actions directed towards governments or corporate entities, often achieving their objectives through the orchestration of disruptive cyber events. In recent years, there has been an observed increase in the use of exploitative cyber events [29,30].

- Sabotage: Sabotage is typically characterized as either ideologically motivated or a tactic employed by state entities to neutralize systems or networks [31,32]. The cyber events that achieve this objective are classified as disruptive cyber events, with the aim of either inflicting a loss of reputation or imposing a significant financial burden.

2.4. The Interaction of Cyber-Events with Motives and Actors

- Disruptive Events: Disruption events are defined as those that deliberately seek to interrupt or hinder the functioning of various systems or services. These events are often initiated by hacktivists, terrorists, and similar actors, with the primary objective being to either influence public opinion or to instill fear [33,34]. Beyond the mere disruption of services, the objectives of these actors frequently entail the extensive damage of existing services and functions, as well as the reputation of their targets [35].

- Exploitative Events: Exploitative events are those that primarily stem from cybercriminals seeking financial gain through theft or ransom [36,37]. Given the sophisticated tactics employed to achieve their objectives, it is imperative to implement continuous updates to cybersecurity protocols across all industry sectors [38,39].

- Mixed Events: The proliferation of cyber-events, encompassing both disruptive and exploitative elements, such as ransomware, necessitates the establishment of a distinct category that incorporates the existing classifications [40,41]. It is evident that the occurrence of such events can lead to the implementation of service disruptions and the exploitation of economic resources.

2.5. Methodology

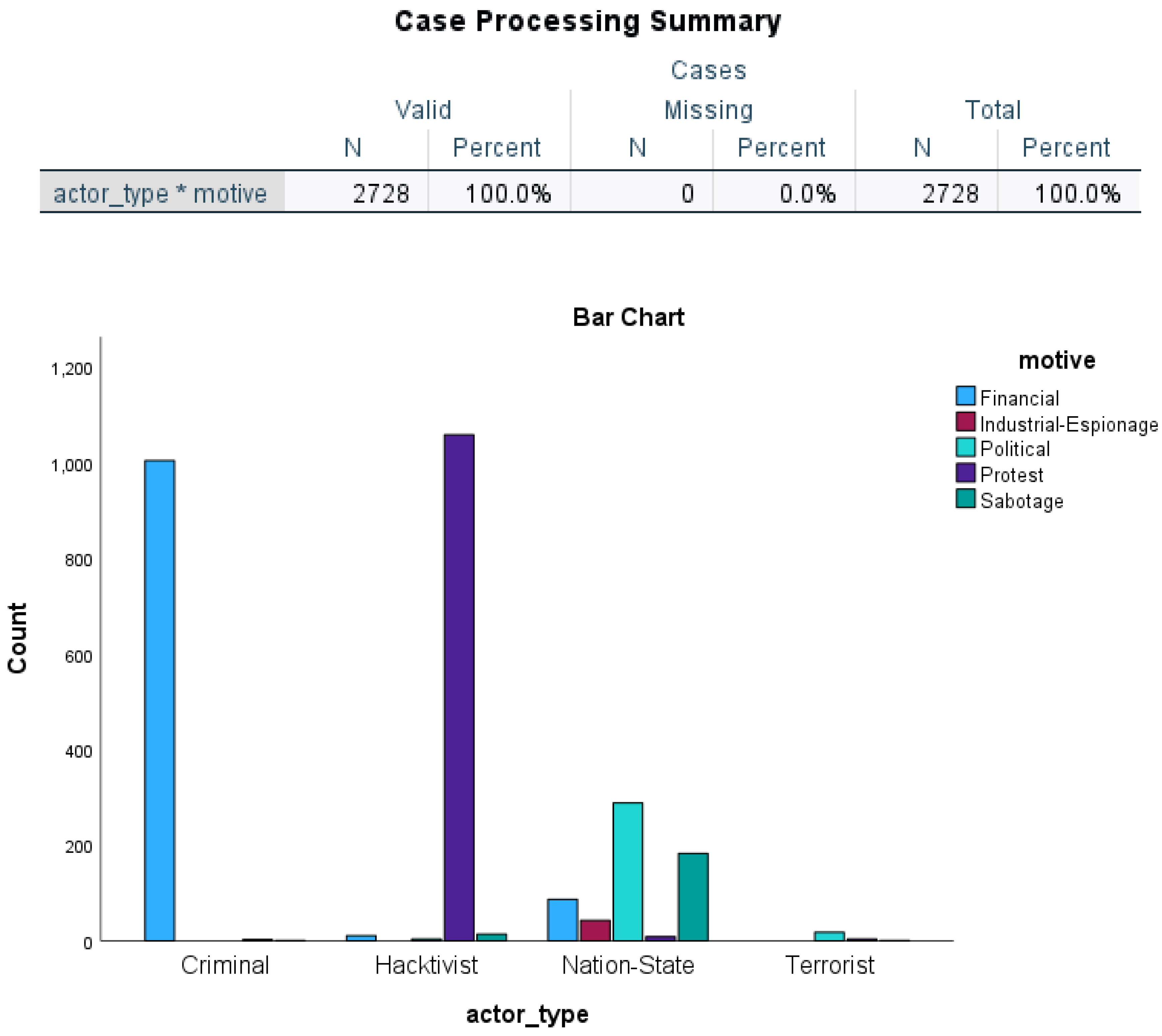

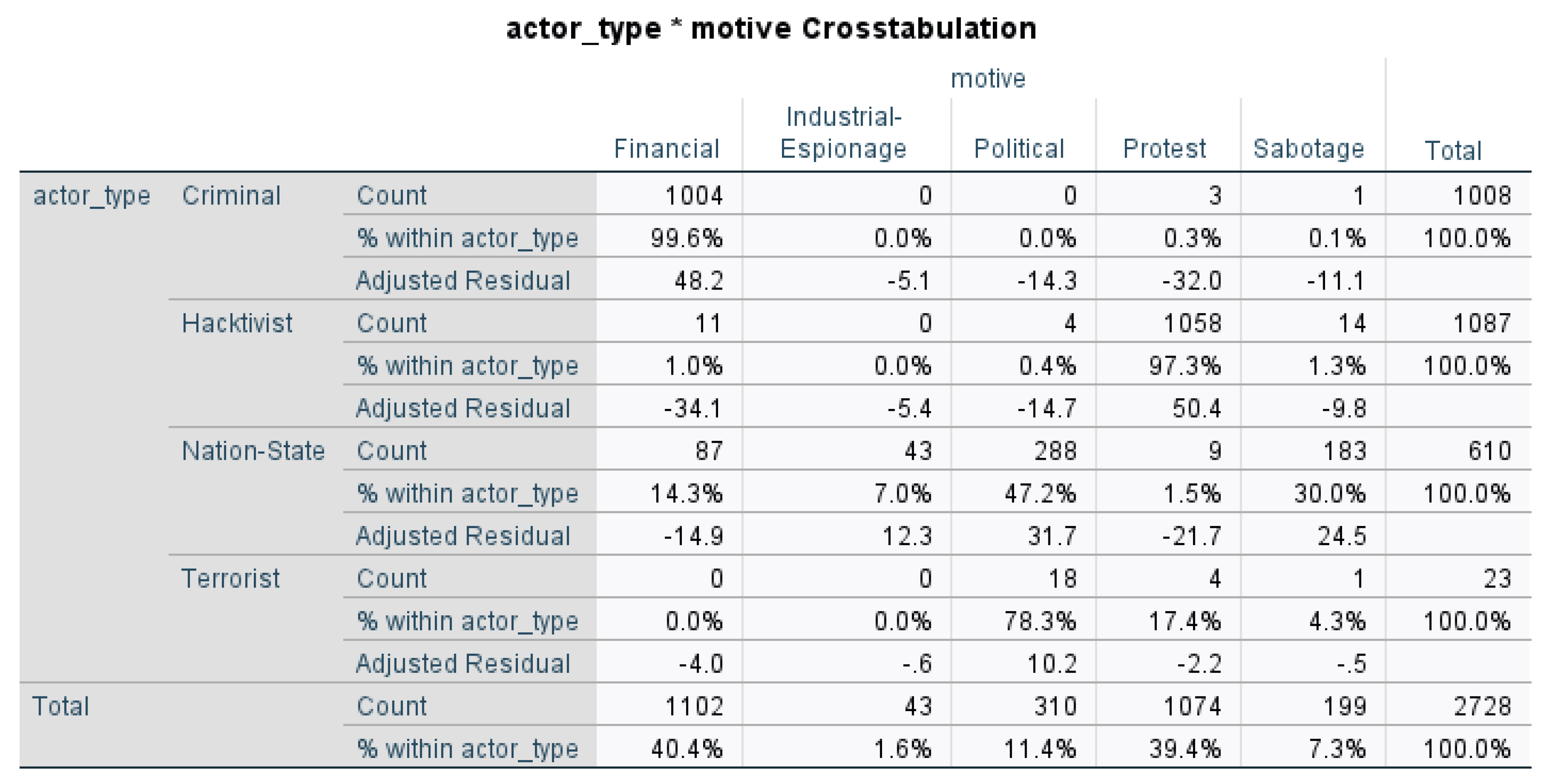

- The actors and the motives.

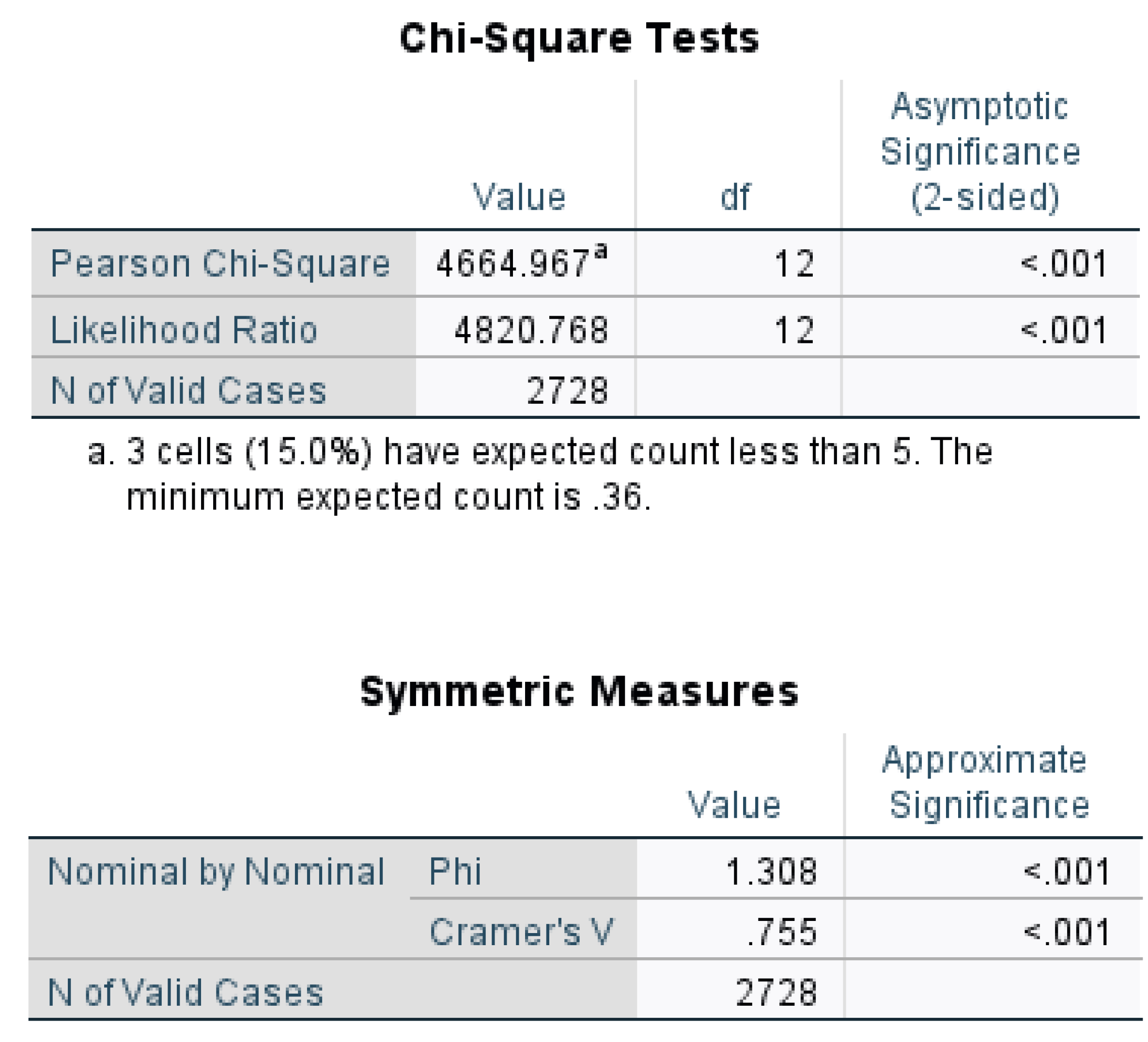

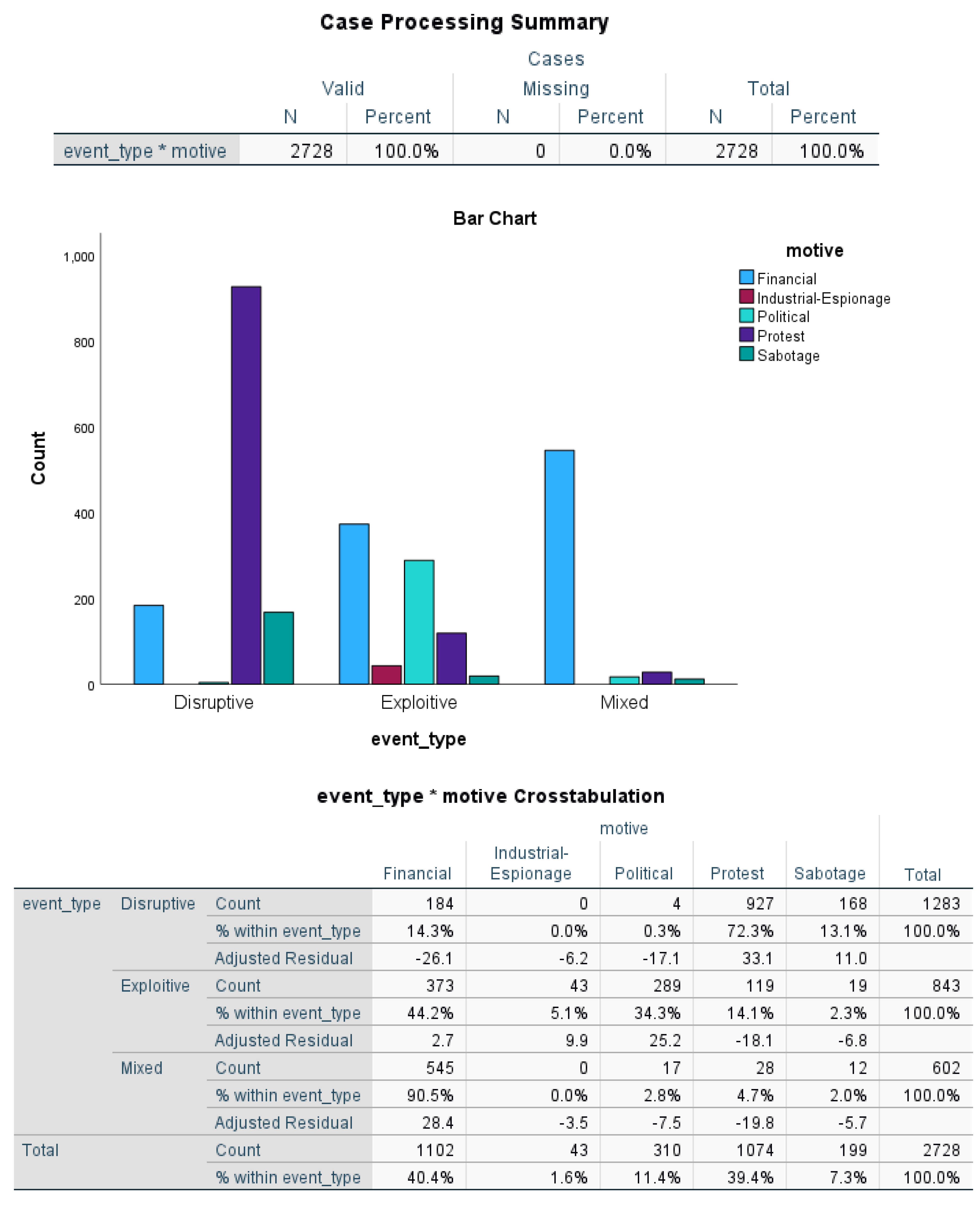

- The event types and the motives.

- Criminal

- Nation-State

- Terrorist

- Hacktivist

- Hobbyist

- Disruptive

- Exploitive

- Mixed

- Protest

- Sabotage

- Espionage

- Financial

3. Results

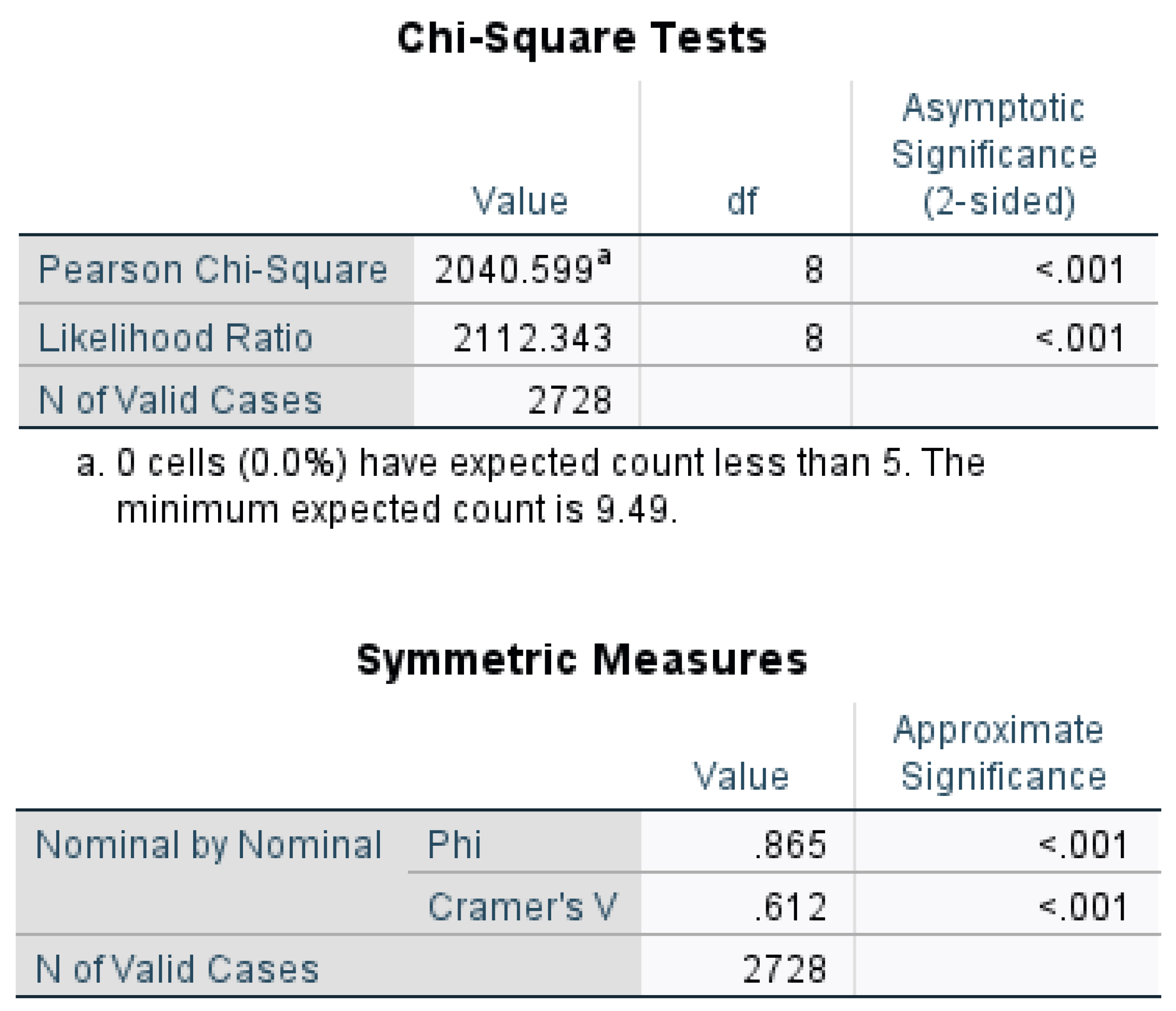

- H0: The null hypothesis posits that "Actor Type is independent of Motive."

- H1: The alternative hypothesis posits that "Actor Type is not independent of Motive."

|

|

|

- The expected cell frequencies all met the required conditions (80% of the cells are greater than or equal to 5).

- There are more than two categories of categorical variables.

- The sample size is large.

- H0: The null hypothesis posits that "Event Type is independent of Motive."

- H1: The alternative hypothesis posits that "Event Type is not independent of Motive."

|

|

- The expected cell frequencies all met the required conditions (80% of the cells are greater than or equal to 5).

- There are more than two categories of categorical variables.

- The sample size is large.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

References

- Banerjee, S., Swearingen, T., Shillair, R., Bauer, J. M., Holt, T. J., & Ross, A. (2021). Using machine learning to examine cyberattack motivations on web defacement data. Social Science Computer Review, 40(4), 914-932. [CrossRef]

- Holt, T. J., Freilich, J. D., & Chermak, S. M. (2017). Exploring the subculture of ideologically motivated cyber-attackers. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 33(3), 212-233. [CrossRef]

- Nedeljković, N., Vugdelija, N., & Kojić, N. (2020). Use of “owasp top 10” in web application security. Fourth International Scientific Conference ITEMA Recent Advances in Information Technology, Tourism, Economics, Management and , 25-30. [CrossRef]

- Heering, M. S., Travaglino, G. A., Abrams, D., & Goldsack, E. (2020). “if they don’t listen to us, they deserve it”: the effect of external efficacy and anger on the perceived legitimacy of hacking. Group Processes &Amp; Intergroup Relations, 23(6), 863-881. [CrossRef]

- Pärn, E. and Edwards, D. J. (2019). Cyber threats confronting the digital built environment. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 26(2), 245-266. [CrossRef]

- https://libguides.library.kent.edu/spss/chisquare.

- Harry, C., & Gallagher, N. (2018). Classifying Cyber Events. Journal of Information Warfare, 17(3), 17-31 https://cissm.umd.edu/sites/default/files/2019-07/Cyber-Taxonomy-101918.pdf.

- https://cissm.umd.edu/cyber-events-database.

- Pseftelis, T. and Chondrokoukis, G. (2025). Understanding cyber incident dynamics in the european union: a study of actor types and sector vulnerabilities. [CrossRef]

- Pawlicka, A., Choraś, M., & Pawlicki, M. (2021). The stray sheep of cyberspace a.k.a. the actors who claim they break the law for the greater good. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 25(5), 843-852. [CrossRef]

- Mihai, I. (2022). Untitled. International Journal of Information Security and Cybercrime, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Alda, E. and Sala, J. L. (2014). Links between terrorism, organized crime and crime: the case of the sahel region. Stability: International Journal of Security &Amp; Development, 3(1). [CrossRef]

- Sukhodolia, O. (2018). Implementation of the concept of critical infrastructure protection in ukraine: achievements and challenges. Information &Amp; Security: An International Journal, 40(2), 107-119. [CrossRef]

- Alkharman, J. and Hassan, I. (2023). Cyberterrorism and self-defense in the framework of international law. Journal of Law and Sustainable Development, 11(8), e1430. [CrossRef]

- Raghuwanshi, P. (2024). Ai-driven identity and financial fraud detection for national security. Journal of Artificial Intelligence General Science (JAIGS) ISSN:3006-4023, 7(01), 38-51. [CrossRef]

- Chang, H. and Hawamdeh, S. (2020). Cybersecurity for information professionals. [CrossRef]

- Cantika, S. and Umniyah, A. (2023). Analysis of the australian government’s security strategy in countering the potential threat of terrorism groups through cyber terrorism instruments. Insignia: Journal of International Relations, 10(2), 214. [CrossRef]

- KOVACI, P. (2024). Threat actors seeking to exploit ai capabilities. types and their goals. Strategic Impact, 89(4), 53-63. [CrossRef]

- Sigholm, J. (2013). Non-state actors in cyberspace operations. Journal of Military Studies, 4(1), 1-37. [CrossRef]

- Rizal, M. and Yani, Y. M. (2016). Cybersecurity policy and its implementation in indonesia. JAS (Journal of ASEAN Studies), 4(1), 61. [CrossRef]

- Sigholm, J. (2013). Non-state actors in cyberspace operations. Journal of Military Studies, 4(1), 1-37. [CrossRef]

- Maimon, D. and Louderback, E. R. (2019). Cyber-dependent crimes: an interdisciplinary review. Annual Review of Criminology, 2(1), 191-216. [CrossRef]

- Habermayer, H. and Schröfl, J. (2014). Genese und wesentliche inhalte der österreichischen strategie für cyber sicherheit (öscs). Sicherheit &Amp; Frieden, 32(1), 28-36. [CrossRef]

- Garty, A. (2023). The digital frontier: defending the public sector against cyberthreats. Network Security, 2023(9). [CrossRef]

- Petrich, K. (2021). The crime–terror nexus. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies. [CrossRef]

- Batueva, E. (2014). Virtual reality: u.s. information security threats concept and its international dimension. MGIMO Review of International Relations, (3(36)), 128-136. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, M. L. and Erickson, C. M. (2025). From elements to effects: the strategic imperative to understand "national cyber power". International Conference on Cyber Warfare and Security, 20(1), 86-92. [CrossRef]

- Albahar, M. A. (2017). Cyber attacks and terrorism: a twenty-first century conundrum. Science and Engineering Ethics, 25(4), 993-1006. [CrossRef]

- Kautwima, P., Haiduwa, T., Sai, K. O. S., Hashiyana, V., & Suresh, N. (2021). System end-user actions as a threat to information system security. International Journal of Network Security &Amp; Its Applications, 13(6), 71-83. [CrossRef]

- Beretas, C. P. (2024). The most important types of cyber attacks that france is expected to face in the future and the cyber security measures it must implement to protect critical infrastructure, telecommunication networks and personal data. Universal Library of Engineering Technology, 01(01), 01-12. [CrossRef]

- Malec, N. (2024). Sztuczna inteligencja a bezpieczeństwo państwa. Prawo I Bezpieczeństwo, (1 (2024)), 20-24. [CrossRef]

- Judijanto, L. (2024). National security strategies amidst increasing global cyber threats: a multilateral approach. Synergisia, 1(2), 11-18. [CrossRef]

- Morris, A. and Meloy, J. R. (2020). A preliminary report of psychiatric diagnoses in a scottish county sample of persons of national security concern. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 65(5), 1638-1645. [CrossRef]

- Lehto, M. (2022). Apt cyber-attack modelling: building a general model. International Conference on Cyber Warfare and Security, 17(1), 121-129. [CrossRef]

- Rath, S. K. (2016). South asia's cyber insecurity: a tale of impending doom. Qatar Foundation Annual Research Conference Proceedings Volume 2016 Issue 1. [CrossRef]

- Heinl, C. H. (2021). Technology. The Oxford Handbook of Cyber Security, 201-220. [CrossRef]

- Olszewski, B. (2018). Advanced persistent threats as a manifestation of states’ military activity in cyber space. Scientific Journal of the Military University of Land Forces, 189(3), 57-71. [CrossRef]

- Turunen, M. and Kari, M. J. (2020). Cyber deterrence and russia’s active cyber defense. Proceedings of the 19th European Conference on Cyber Warfare. [CrossRef]

- Florido-Benítez, L. (2024). The types of hackers and cyberattacks in the aviation industry. Journal of Transportation Security, 17(1). [CrossRef]

- Стригунoв, К. С. (2023). Hybridization of international terrorism and transnational crime at the present stage. Istoriya, 14(4 (126)), 0. [CrossRef]

- Grytsyshen, D. (2020). Methodology of implementation of the state criminal policy in the field of prevention and counteraction to economic crime in the context of interaction with other types of state policy. Public Administration Aspects, 8(5), 97-106. [CrossRef]

- https://cissm.umd.edu/research-impact/publications/cyber-events-database-home.

- Saeed, S., Suayyid, S. A., Al-Ghamdi, M. S., Almuhaisen, H. A., & Almuhaideb, A. M. (2023). A systematic literature review on cyber threat intelligence for organizational cybersecurity resilience. Sensors, 23(16), 7273. [CrossRef]

- Cheung-Blunden, V., Cropper, K., Panis, A., & Davis, K. (2019). Functional divergence of two threat-induced emotions: fear-based versus anxiety-based cybersecurity preferences.. Emotion, 19(8), 1353-1365. [CrossRef]

- Chimezie, O., Akagha, O. V., Dawodu, S. O., Anyanwu, A., Onwusinkwue, S., & Ahmad, I. A. I. (2024). Comprehensive review on cybersecurity: modern threats and advanced defense strategies. Computer Science &Amp; IT Research Journal, 5(2), 293-310. [CrossRef]

- Bocharova, A. (2024). Information security and cybersecurity policy. World Economy and International Relations, 68(4), 121-130. [CrossRef]

- Gombár, M., Vagaská, A., Korauš, A., & Račková, P. (2024). Application of structural equation modelling to cybersecurity risk analysis in the era of industry 4.0. Mathematics, 12(2), 343. [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, T. O., Farayola, O. A., Kaggwa, S., Uwaoma, P. U., Hassan, A. O., & Dawodu, S. O. (2024). Cybersecurity awareness and education programs: a review of employee engagement and accountability. Computer Science &Amp; IT Research Journal, 5(1), 100-119. [CrossRef]

- Mavroeidis, V., Hohimer, R. E., Casey, T., & Jesang, A. (2021). Threat actor type inference and characterization within cyber threat intelligence. 2021 13th International Conference on Cyber Conflict (CyCon), 327-352. [CrossRef]

- Holding, A. C., Barlow, M., Koestner, R., & Wrosch, C. (2019). Why are we together? a dyadic longitudinal investigation of relationship motivation, goal progress, and adjustment. Journal of Personality, 88(3), 464-477. [CrossRef]

- Sundjaja, A. M., Ridwan, A., Robbani, D., & Soemantri, R. A. (2024). Impact of 'don't know? kasih no!' campaign on cybersecurity awareness: unraveling the links to user satisfaction, trust, and commitment. International Journal of Safety and Security Engineering, 14(5), 1577-1589. [CrossRef]

- Srivast, A., Hussain, M. M., Sadanandan, S. K., Sarwari, A. R., & Reece, R. (2023). Building cyber-attack immunity in electric energy system inspired by infectious disease ecology. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).