Submitted:

12 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Rearing, Fungal Strains, and Culture Conditions

2.2. Microscopy

3. Results

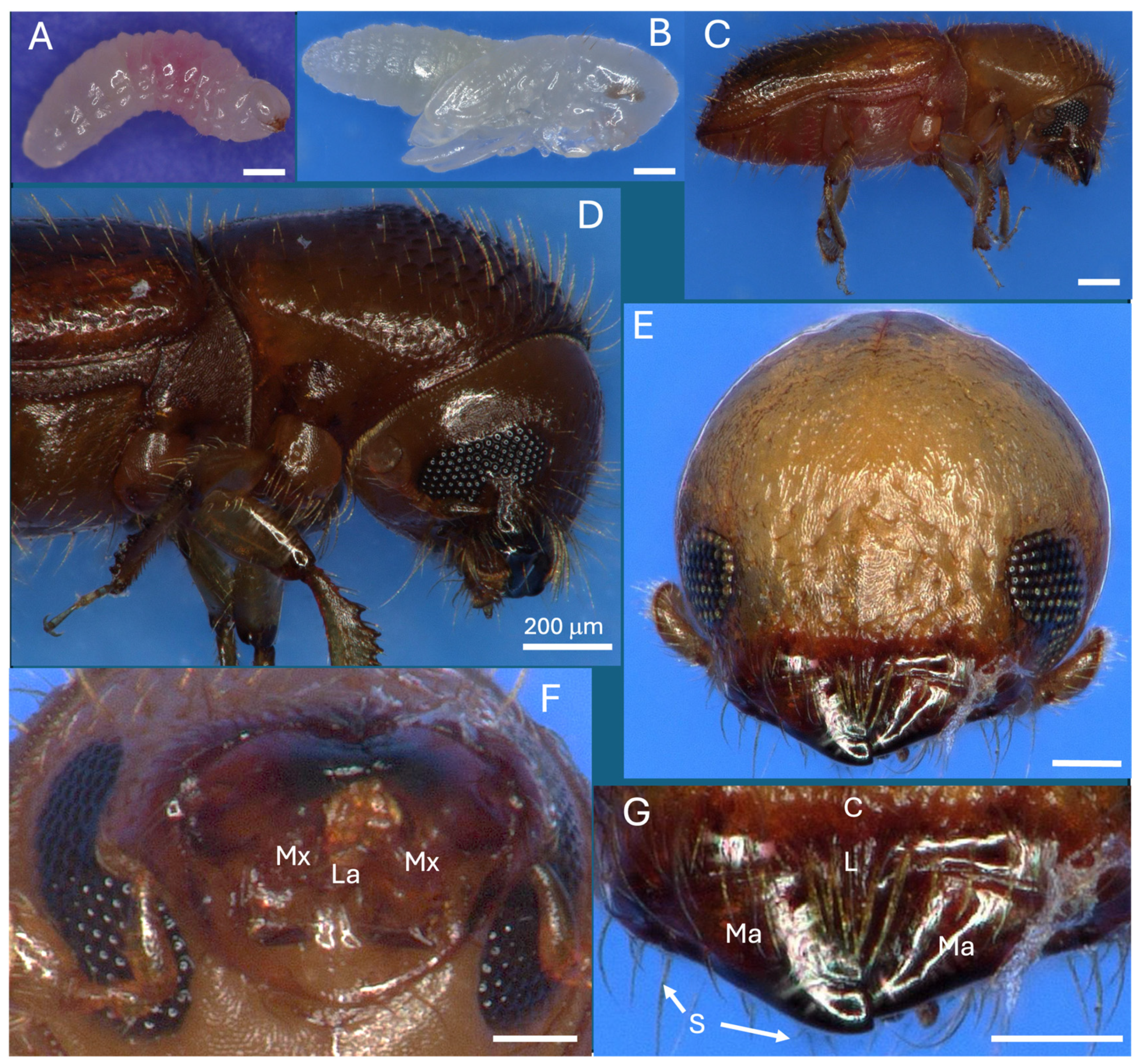

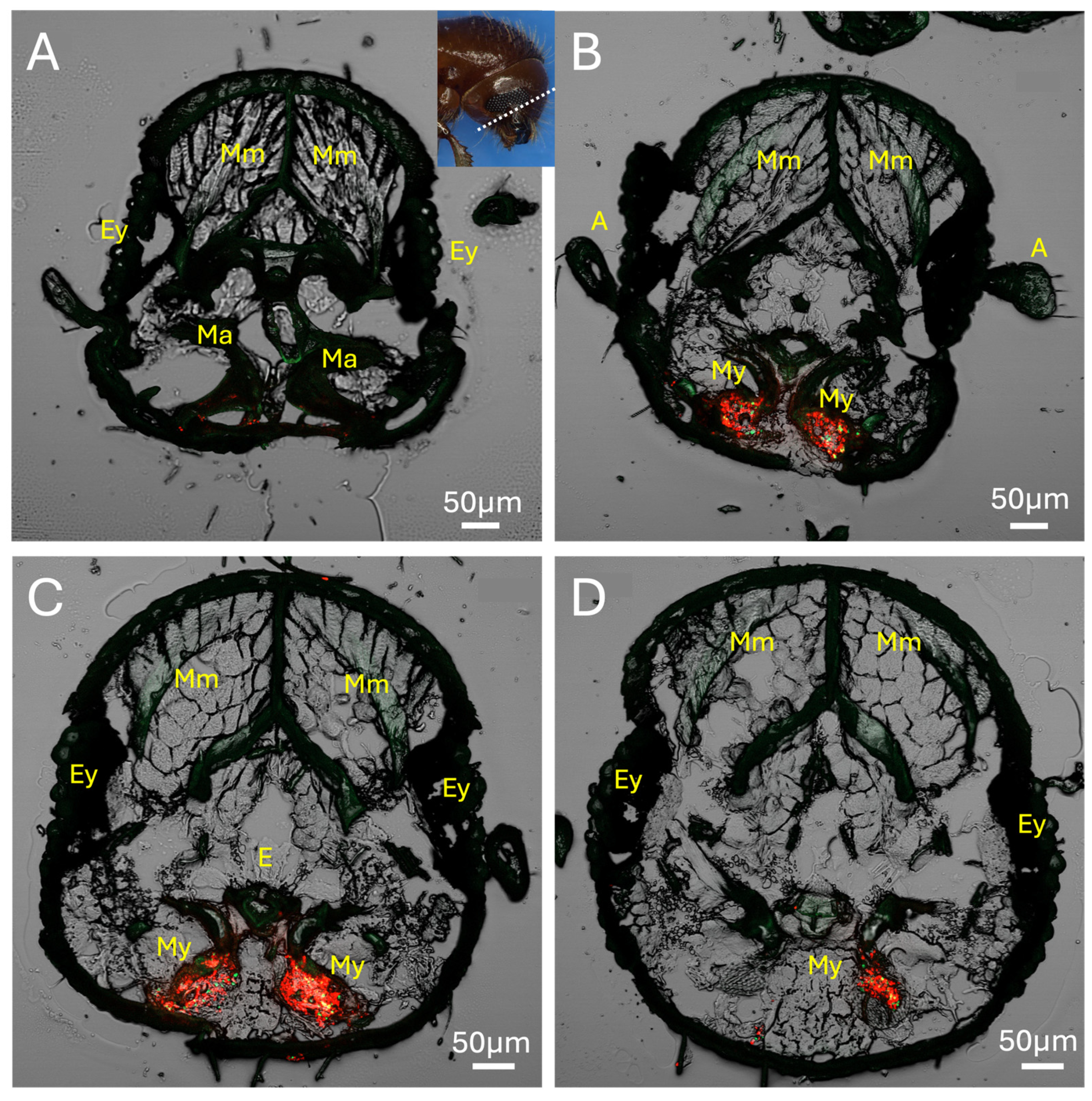

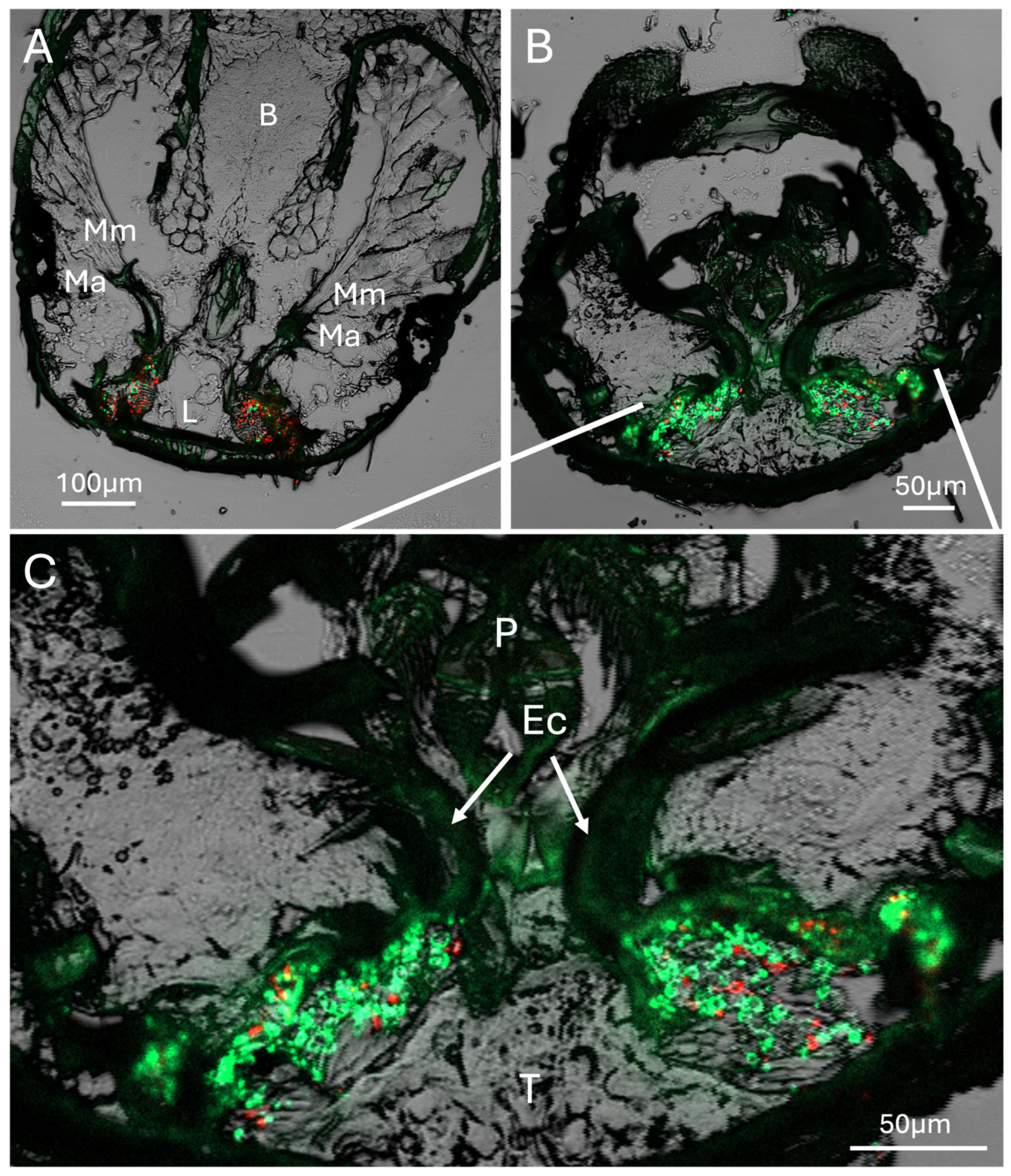

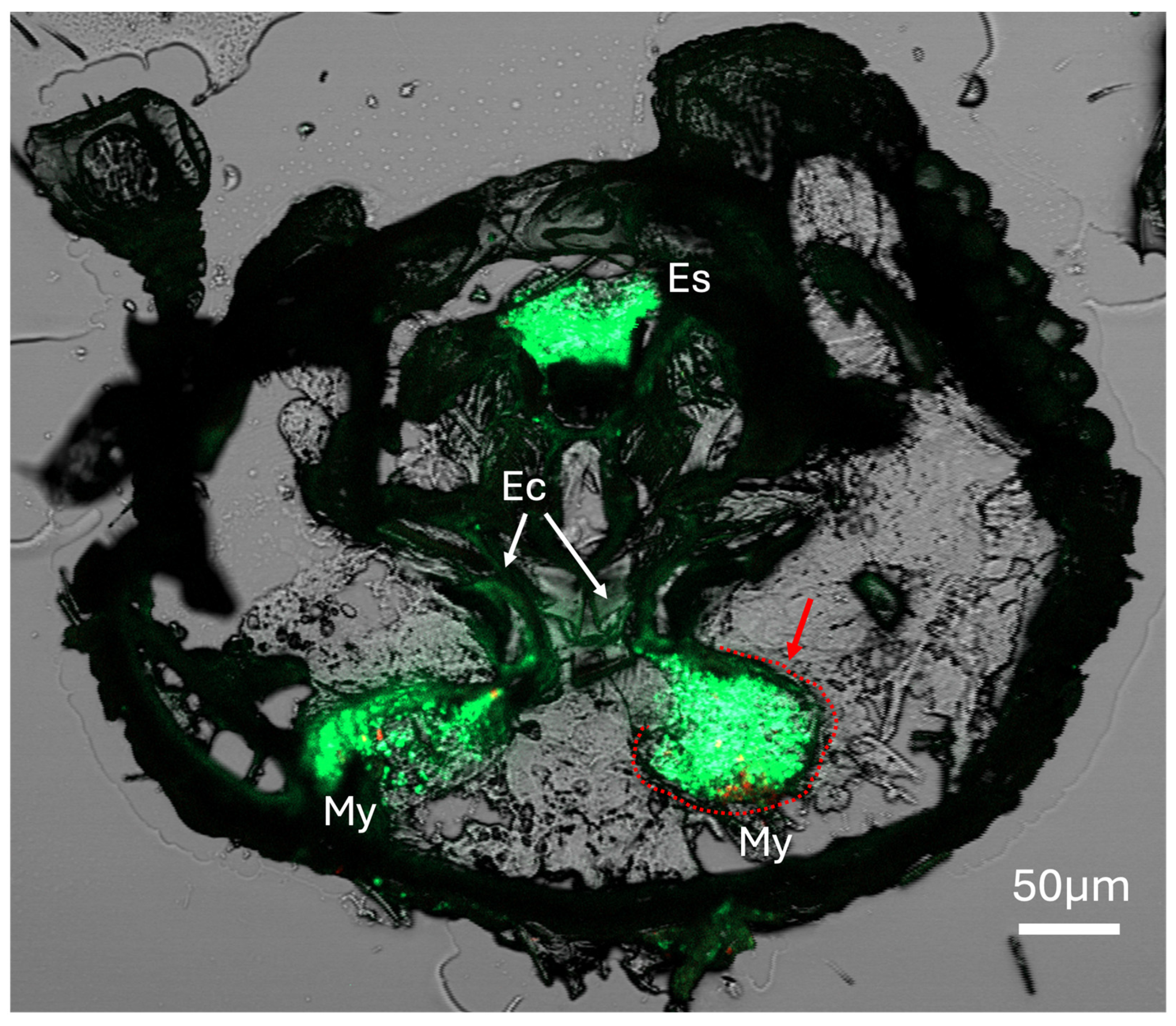

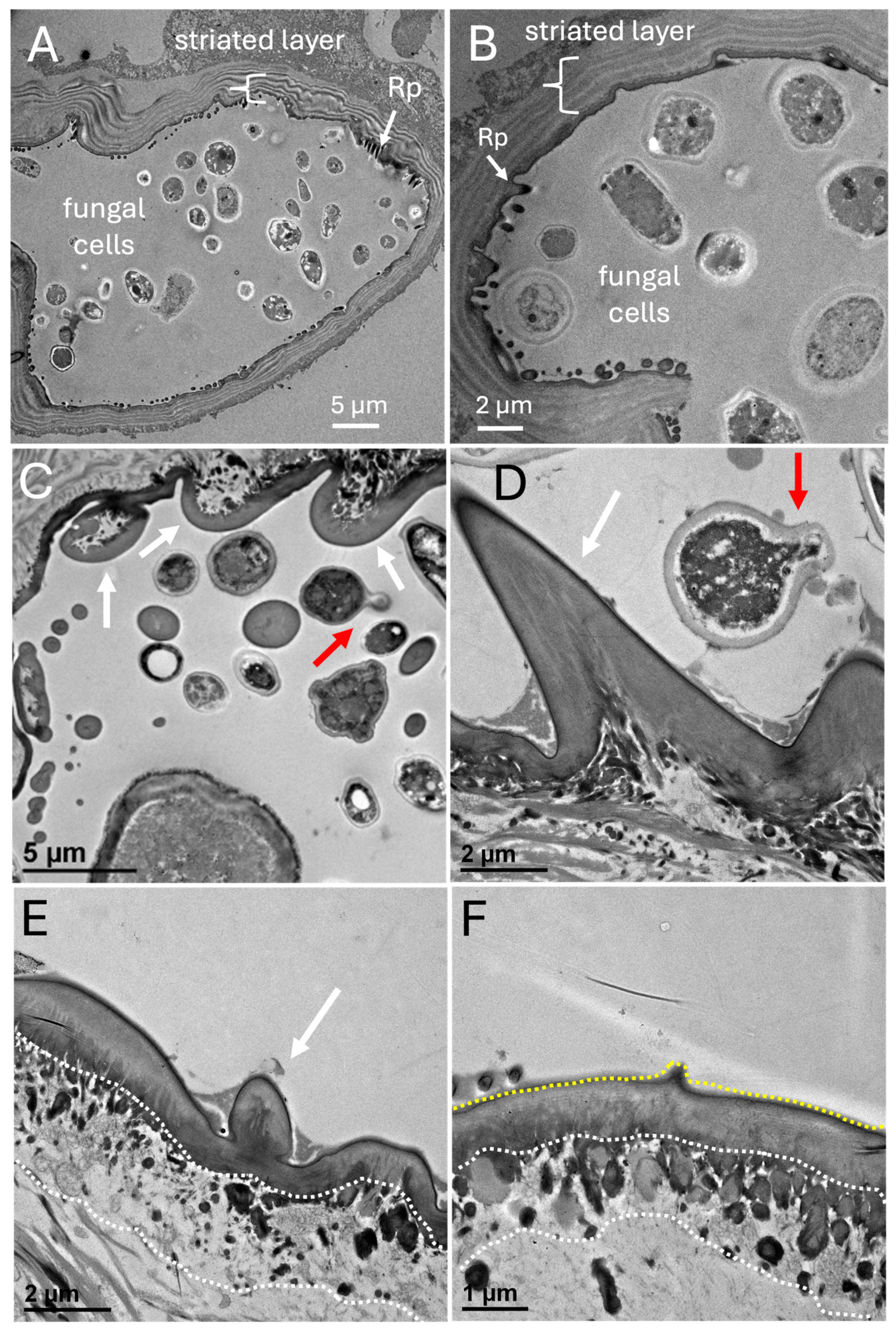

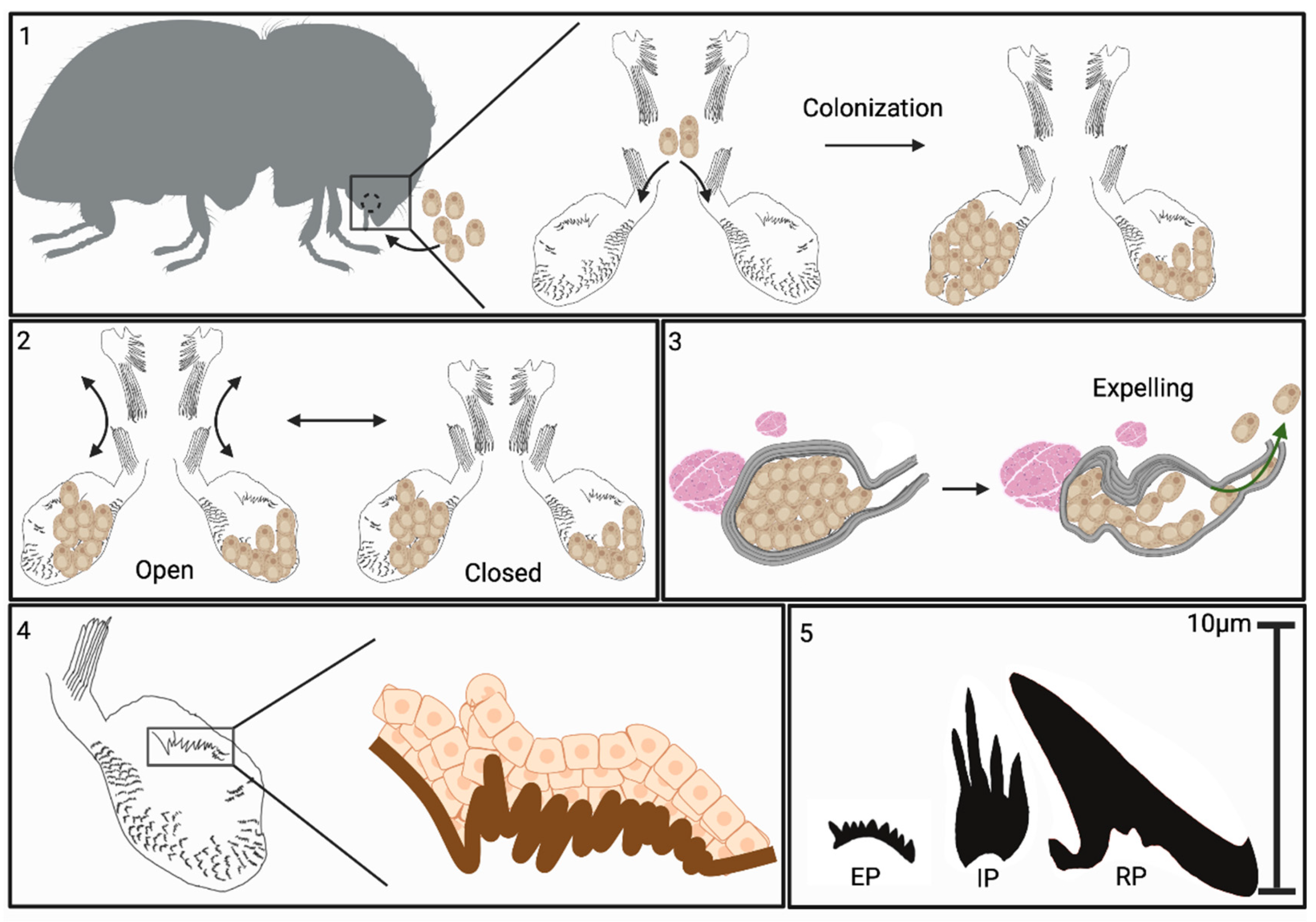

3.1. Mandible, Muscle, and Cross-Section Analyses of the X. affinis Mycangia

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dzurenko, M.; Hulcr, J. Ambrosia beetles. Current Biology 2022, 32, R61–R62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, R.; Keyhani, N. Fungal mutualisms and pathosystems: life and death in the ambrosia beetle mycangia. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2021, 105, 3393–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderpool, D.; Bracewell, R.R.; McCutcheon, J.P. Know your farmer: Ancient origins and multiple independent domestications of ambrosia beetle fungal cultivars. Molecular Ecology 2018, 27, 2077–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedermann, P.; Vega, F.; Douglas, A. Ecology and evolution of insect-fungus mutualisms. Annual Review of Entomology, Vol 65 2020, 65, 431–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bateman, C.; Skelton, J.; Wang, B.; Black, A.; Huang, Y.; Gonzalez, A.; Jusino, M.; Nolen, Z.; Freeman, S.; et al. Preinvasion assessment of exotic bark beetle-vectored fungi to detect tree-killing pathogens. Phytopathology 2022, 112, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulcr, J.; Gomez, D.; Skelton, J.; Johnson, A.; Adams, S.; Li, Y.; Jusino, M.; Smith, M. Invasion of an inconspicuous ambrosia beetle and fungus may affect wood decay in Southeastern North America. Biological Invasions 2021, 23, 1339–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Gao, J.; Hulcr, J. Insect wood borers on commercial North American tree species growing in China: review of Chinese peer-review and grey literature. Environmental Entomology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Johnson, A.; Gao, L.; Wu, C.; Hulcr, J. Two new invasive Ips bark beetles (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in mainland China and their potential distribution in Asia. Pest Management Science 2021, 77, 4000–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, D.; Johnson, A.; Hulcr, J. Potential pest bark and ambrosia beetles from Cuba not present in the continental United States. Florida Entomologist 2020, 103, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, K.M.; Adams, D.C.; Klepzig, K.D.; Hulcr, J. When does invasive species removal lead to ecological recovery? Implications for management success. Biological Invasions 2018, 20, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibold, S.; Muller, J.; Baldrian, P.; Cadotte, M.; Stursova, M.; Biedermann, P.; Krah, F.; Bassler, C. Fungi associated with beetles dispersing from dead wood - Let’s take the beetle bus! Fungal Ecology 2019, 39, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelton, J.; Johnson, A.; Jusino, M.; Bateman, C.; Li, Y.; Hulcr, J. A selective fungal transport organ (mycangium) maintains coarse phylogenetic congruence between fungus-farming ambrosia beetles and their symbionts. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 2019, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo, J.; Rugman-Jones, P.; Husein, D.; Stajich, J.; Kasson, M.; Carrillo, D.; Stouthamer, R.; Eskalen, A. Members of the Euwallacea fornicatus species complex exhibit promiscuous mutualism with ambrosia fungi in Taiwan. Fungal Genetics and Biology 2019, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucedo-Carabez, J.R.; Ploetz, R.C.; Konkol, J.L.; Carrillo, D.; Gazis, R. Partnerships between ambrosia beetles and fungi: lineage-specific promiscuity among vectors of the laurel wilt pathogen, Raffaelea lauricola. Microb Ecol 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostovcik, M.; Bateman, C.; Kolarik, M.; Stelinski, L.; Jordal, B.; Hulcr, J. The ambrosia symbiosis is specific in some species and promiscuous in others: evidence from community pyrosequencing. Isme Journal 2015, 9, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francke-Grossmann, H. Ectosymbiosis in wood-inhabiting insects. In Symbiosis: Associations of invetebrates birds, ruminants and other biota, Henry, S.M., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, 1967; Volume II, pp. 142–206. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Ruan, Y.; Kasson, M.; Stanley, E.; Gillett, C.; Johnson, A.; Zhang, M.; Hulcr, J. Structure of the ambrosia beetle (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) mycangia revealed through micro-computed tomography. Journal of Insect Science 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.J.; McKenna, D.D.; Jordal, B.H.; Cognato, A.I.; Smith, S.M.; Lemmon, A.R.; Lemmon, E.M.; Hulcr, J. Phylogenomics clarifies repeated evolutionary origins of inbreeding and fungus farming in bark beetles (Curculionidae, Scolytinae). Mol Phylogenet Evol 2018, 127, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, L.R. Ambrosia fungi: extent of specificity to ambrosia beetles. Science 1966, 153, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayers, C.G.; Harrington, T.C.; Biedermann, P.H.W. Mycangia define the diverse ambrosia beetle–fungus symbioses. In The Convergent Evolution of Agriculture in Humans and Insects; Schultz, T.R., Gawne, R., Peregrine, P.N., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 2022; pp. 105–142. [Google Scholar]

- Mayers, C.; Harrington, T.; Mcnew, D.; Roeper, R.; Biedermann, P.; Masuya, H.; Bateman, C. Four mycangium types and four genera of ambrosia fungi suggest a complex history of fungus farming in the ambrosia beetle tribe Xyloterini. Mycologia 2020, 112, 1104–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Simmons, D.R.; Bateman, C.C.; Short, D.P.G.; Kasson, M.T.; Rabaglia, R.J.; Hulcr, J. New fungus-insect symbiosis: culturing, molecular, and histological methods determine saprophytic Polyporales mutualists of Ambrosiodmus ambrosia beetles. Plos One 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spahr, E.; Kasson, M.; Kijimoto, T. Micro-computed tomography permits enhanced visualization of mycangia across development and between sexes inEuwallaceaambrosia beetles. Plos One 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.R.; Kinoshita, S.; Sasaki, O.; Cognato, A.I.; Kajimura, H. Non-destructive observation of the mycangia of Euwallacea interjectus (Blandford) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) using X-ray computed tomography. Entomological Science 2019, 22, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploetz, R.C.; Hulcr, J.; Wingfield, M.J.; de Beer, Z.W. Destructive tree diseases associated with ambrosia and bark beetles: black swan events in tree pathology? Plant Disease 2013, 97, 856–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ploetz, R.C.; Konkol, J.L.; Narvaez, T.; Duncan, R.E.; Saucedo, R.J.; Campbell, A.; Mantilla, J.; Carrillo, D.; Kendra, P.E. Presence and prevalence of Raffaelea lauricola, cause of laurel wilt, in different species of ambrosia beetle in Florida, USA. J Econ Entomol 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, J.E.; Carrillo, D.; Duncan, R.E.; Capinera, J.L.; Brar, G.; Mclean, S.; Arpaia, M.L.; Focht, E.; Smith, J.A.; Hughes, M.; et al. Susceptibility of Persea spp. and other Lauraceae to attack by redbay ambrosia beetle, Xyleborus glabratus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae). Florida Entomologist 2012, 95, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraedrich, S.W.; Harrington, T.C.; Rabaglia, R.J.; Ulyshen, M.D.; Mayfield, A.E.; Hanula, J.L.; Eickwort, J.M.; Miller, D.R. A fungal symbiont of the redbay ambrosia beetle causes a lethal wilt in redbay and other Lauraceae in the Southeastern United States. Plant Disease 2008, 92, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucedo, J.R.; Ploetz, R.C.; Konkol, J.L.; Angel, M.; Mantilla, J.; Menocal, O.; Carrillo, D. Nutritional symbionts of a putative vector, Xyloborus bispinatus, of the laurel wilt pathogen of avocado, Raffaelea lauricola. Symbiosis 2017, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, R.; Bansal, K.; Keyhani, N.O. Host switching by an ambrosia beetle fungal mutualist: Mycangial colonization of indigenous beetles by the invasive laurel wilt fungal pathogen. Environ Microbiol 2023, 25, 1894–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menocal, O.; Cruz, L.F.; Kendra, P.E.; Berto, M.; Carrillo, D. Flexibility in the ambrosia symbiosis of Xyleborus bispinatus. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1110474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, L.F.; Menocal, O.; Mantilla, J.; Ibarra-Juarez, L.A.; Carrillo, D. Xyleborus volvulus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae): Biology and Fungal Associates. Appl Environ Microbiol 2019, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lu, D.; Joseph, R.; Li, T.; Keyhani, N. High efficiency transformation and mutant screening of the laurel wilt pathogen, Raffaelea lauricola. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2020, 104, 7331–7343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.-R.; Kinoshita, S.; Sasaki, O.; Cognato, A.I.; Kajimura, H. Non-destructive observation of the mycangia of Euwallacea interjectus (Blandford) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) using X-ray computed tomography. Entomological Science 2019, 22, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spahr, E.; McLaughlin, S.; Tichinel, A.; Kasson, M.; Kijimoto, T. Staining and scanning protocol for micro-computed tomography to observe the morphology of soft tissues in ambrosia beetles. Bio-Protocol 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, C.; Huang, Y.T.; Simmons, D.R.; Kasson, M.T.; Stanley, E.L.; Hulcr, J. Ambrosia beetle Premnobius cavipennis (Scolytinae: Ipini) carries highly divergent ascomycotan ambrosia fungus, Afroraffaelea ambrosiae gen. nov et sp nov (Ophiostomatales). Fungal Ecology 2017, 25, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasson, M.T.; Wickert, K.L.; Stauder, C.M.; Macias, A.M.; Berger, M.C.; Simmons, D.R.; Short, D.P.G.; DeVallance, D.B.; Hulcr, J. Mutualism with aggressive wood-degrading Flavodon ambrosius (Polyporales) facilitates niche expansion and communal social structure in Ambrosiophilus ambrosia beetles. Fungal Ecology 2016, 23, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spahr, E.J.; Wasef, F.; Kasson, M.T.; Kijimoto, T. Developmental genetic underpinnings of a symbiosis-associated organ in the fungus-farming ambrosia beetle Euwallacea validus. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 14014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).