1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most frequent neurodegenerative disorder worldwide, following Alzheimer’s disease. It is a movement disorder that encompasses motor symptoms — resting tremor, muscle rigidity, bradykinesia, postural instability, and gait freezing [

1] — and non-motor symptoms as well [

2]. They result from alpha-synuclein accumulation and peripheral and central neurodegenerative processes, affecting the dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra [

1]. Pathogenically, PD likely encompasses many genetic–molecular entities, resulting in lesions in different structures within the central and peripheral nervous system. The deposition of alpha-synuclein in the cellular soma, leading to the formation of Lewy bodies, appears to be one of the main events leading to neurodegeneration and, eventually, dementia [

3]. Other factors contributing to the neurodegenerative process include mitochondrial dysfunction, synaptic alterations, the disruption of calcium homeostasis, and neuroinflammation [

3].

Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) is a group of concurring conditions, including insulin resistance, that increase the risk of heart disease, stroke, and diabetes [

4]. It is a cluster of five interrelated risk factors: high blood pressure, high blood sugar, high levels of triglycerides, low levels of HDL and a large waist circumference. MetS is associated with developing several diseases, including heart disease, stroke, and type-2 diabetes. It is also associated with an increased all-cause mortality risk [

4]. In a molecular level, oxidative stress has been found to be a major component of MetS and associated diseases [

4], as well as in PD [

5].

Growing evidence indicates that patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) who also meet criteria for metabolic syndrome (MetS) may present with more severe clinical manifestations [

6]. In particular, one study reported significantly higher total scores on the Non-Motor Symptoms Scale (NMSS) among patients with MetS compared with those without MetS or with at most two of its components [

7]. However, the genetic mechanisms underlying the relationship between MetS and PD remain largely unexplored.

This study aimed to explore the possible impact of MetS on motor and non-motor symptoms’ severity and evolution in patients with newly diagnosed PD, and to assess the genetic traits associated with both MetS and PD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

This study included 423 untreated, newly diagnosed PD patients from the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) study [

5]. The inclusion criteria were: 1) a 2-year PD history, 2) a Hoehn and Yahr stage I or II at enrollment, 3) a dopamine transporter-protein deficit measured by single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), 4) no clinical expectation of starting PD medication until 6 months after the initial evaluation.

Institutional review boards at participating clinical sites approved the PPMI study protocol. Before being included in the study, all participants signed a written informed consent whereby the result would be shared with involved and non-involved investigators [

5].

2.2. Study Assessments

This was a cohort study of data retrieved from the PPMI data-base. Patients were assessed during a first visit, to set baselines scores, and over the following 5 years. The evolution of PD symptoms was measured by the MDS-UPDRS, a scale used to measure the impact of Parkinson's disease on patients. It assesses non-motor experiences of daily living, motor experiences of daily living, motor symptoms and motor complications of treatment (parts I, II, III, IV respectively) [

6]. Each part comprises a series of items that are rated from normal to severe (0-4) according to the progression of symptoms. The first part of the questionnaire focuses on mental health, cognitive impairment, and non-motor symptoms. The second part assesses motor impairments in daily life activities. Part III collects information based on the motor examination. Finally, Part IV evaluates motor complications associated with the use of antiparkinsonian medications, including motor fluctuations and dyskinesias [

7]. For our study, MDS-UPDRS total score and subscores from Parts I to IV were analyzed. Motor examination (i.e., Part III) was assessed in the medication-free condition, defined as off-condition for practical purposes.

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) status at baseline was determined according to the Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) criteria [

7]. A diagnosis of MetS required the presence of at least three out of the following five components: (1) obesity, defined as a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m²; (2) hyperglycemia, indicated by a fasting glucose level above 100 mg/dL, a previous diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, or current treatment for diabetes; (3) hypertriglyceridemia, defined as triglyceride levels of 150 mg/dL or higher, a previous diagnosis or treatment; (4) low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, defined as HDL < 40 mg/dL in men or < 50 mg/dL in women, a previous diagnosis or treatment; and (5) hypertension, defined as systolic/diastolic blood pressure above 130/85 mm Hg, a prior diagnosis or current treatment.

2.3. Assessments of Genetic Variants in PD Patients with or Without MetS

These methods have been discussed in detail in previous publications [

8]. Whole-genome sequencing was performed using a Macrogen Inc. sequencer on whole blood-extracted DNA samples [

9]. The blood sample was obtained during the initial visit. Briefly, 1 µg of each DNA sample was fragmented with Covaris System and prepared following the Illumina TruSeq DNA Sample preparation guide to obtain a final library of 300-400 bp (base pairs) average insert size. Libraries were multiplexed and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq X platform. Paired-end read sequences were aligned to the GRCh37-hs37d5 genome using the Burrows-Wheeler aligner-maximal exact matches algorithm (BWA-MEM v0.7.13). The Bamsormadup2 tool (v2.0.87) was used to filter duplicates and sort aligned bam files. After filtering duplicated read sequences, the reads were realigned and recalibrated using the GATK pipeline (v3.5). Haplotype caller in the GATK pipeline was used to call variants, including single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small In/Dels, and to generate genome VCFs. Using the hg38 aligned cohort VCF files from the whole-genome sequencing data, genotype information was extracted using BCF tools and PLINK. We considered the alleles of the 72 variants available in the PPMI database that are associated with an increased PD risk, as identified in a recent large case-control study [

10]. We focused on SNPs with a minimum call rate of 95%, a minor allele frequency (MAF) > 1%, and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium p-values > 0.05.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Between-group differences were analyzed using t-tests (numerical variables) or chi-sq tests (categorical variables). The evolution of the subjects with and without MetS was compared using General Estimation Equations (GEE). GEE is a broad statistical method used to model longitudinal or clustered data that other statistical techniques cannot adequately handle [

11]. In this model, the outcome was the MDS-UPDRS total score at each visit, and MetS status (yes/no) and time (follow-up year) were included as factors. Sex, age, and the use of antiparkinsonian medications were included as covariates to control for potential confounding factors. To evaluate whether the rate of change in MDS-UPDRS scores over time differed between patients with and without metabolic syndrome (MetS), we included an interaction term between time and MetS status in the model. A significant interaction would indicate that symptom progression follows a different trajectory across the two groups. When the interaction was significant, post hoc comparisons of model-predicted marginal means were carried out at each time point to assess between-group differences.

A logistic regression analysis identified SNPs independently associated with MetS. The Akaike Information Component (AIC) determined the genetic model that best fitted the data among the following ones: 1. “dominant” (i.e., when having one copy of the SNP modified the risk of the outcome); 2. “recessive” (i.e., the risk of the outcome was only modified by the presence of the SNP in both alleles); and 3. “additive” (i.e., having one or two copies of the SNP affected differently the risk of the outcome) ones. We selected the model with the highest AIC to be included in the final multivariate model.

A logistic regression analysis (adjusted for age and sex) was used to test each SNP’s association with MetS status. For each variant, we evaluated dominant, recessive, and additive genetic models, and selected the model with the lowest AIC (best fit) for further consideration. Variants that showed a nominal association with MetS (p < 0.15) in these analyses were then included in a multivariate logistic regression to identify independent effects. The final multivariate model included the selected SNPs and was adjusted for age and sex. The significance level was set at 0.05. Analyses were performed with SPSS v24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R 4.2.2 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 423 patients with Parkinson’s disease were analyzed, of whom 34 (8.0%) met criteria for metabolic syndrome (MetS) at baseline. Patients with MetS (PD+MetS) differed significantly from those without (PD–MetS) in several baseline characteristics (Table 1). Specifically, the MetS group was predominantly male (94% vs. 63% in PD-MetS; p<0.01) and slightly older (mean age 64.9 ± 9.4 vs. 61.4 ± 9.7 years; p=0.04). They also had more advanced disease: a higher proportion were Hoehn and Yahr stage II at baseline (76% vs. 54%; p=0.01), whereas stage I was correspondingly less common (Table 1). Baseline MDS-UPDRS total scores were higher in PD+MetS (30.7 ± 9.6) than in PD-MetS (26.5 ± 11.2; p=0.03), indicating greater overall symptom burden. In contrast, the prevalence of a family history of Parkinson’s disease did not differ between groups (24% vs. 32%, p=0.38).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of PD patients with and without metabolic syndrome.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of PD patients with and without metabolic syndrome.

| |

PD+MetS (n=34) |

PD-MetS (n=389) |

p-value |

| Patients’ characteristics |

|

|

|

| Male sex |

32 (94%) |

246 (63%) |

<0.01 |

| Age |

64.9±9.4 |

61.4±9.7 |

0.04 |

| PD family history |

8 (24%) |

126 (32%) |

0.38 |

| Hoehn and Yahr score |

|

|

|

| I |

8 (24%) |

177 (46%) |

0.01 |

| II |

26 (76%) |

212 (54%) |

|

| MDS-UPDRS Total score |

30.7±9.6 |

26.5±11.2 |

0.03 |

| MetS components |

|

|

|

| Body mass Index |

29 (85%) |

241 (62%) |

<0.01 |

| Hyperglycemia |

17 (50%) |

5 (1%) |

<0.01 |

| Low HDL-C |

13 (38%) |

23 (6%) |

<0.01 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia |

19 (56%) |

11 (3%) |

<0.01 |

| Hypertension |

28 (83%) |

255 (66%) |

0.02 |

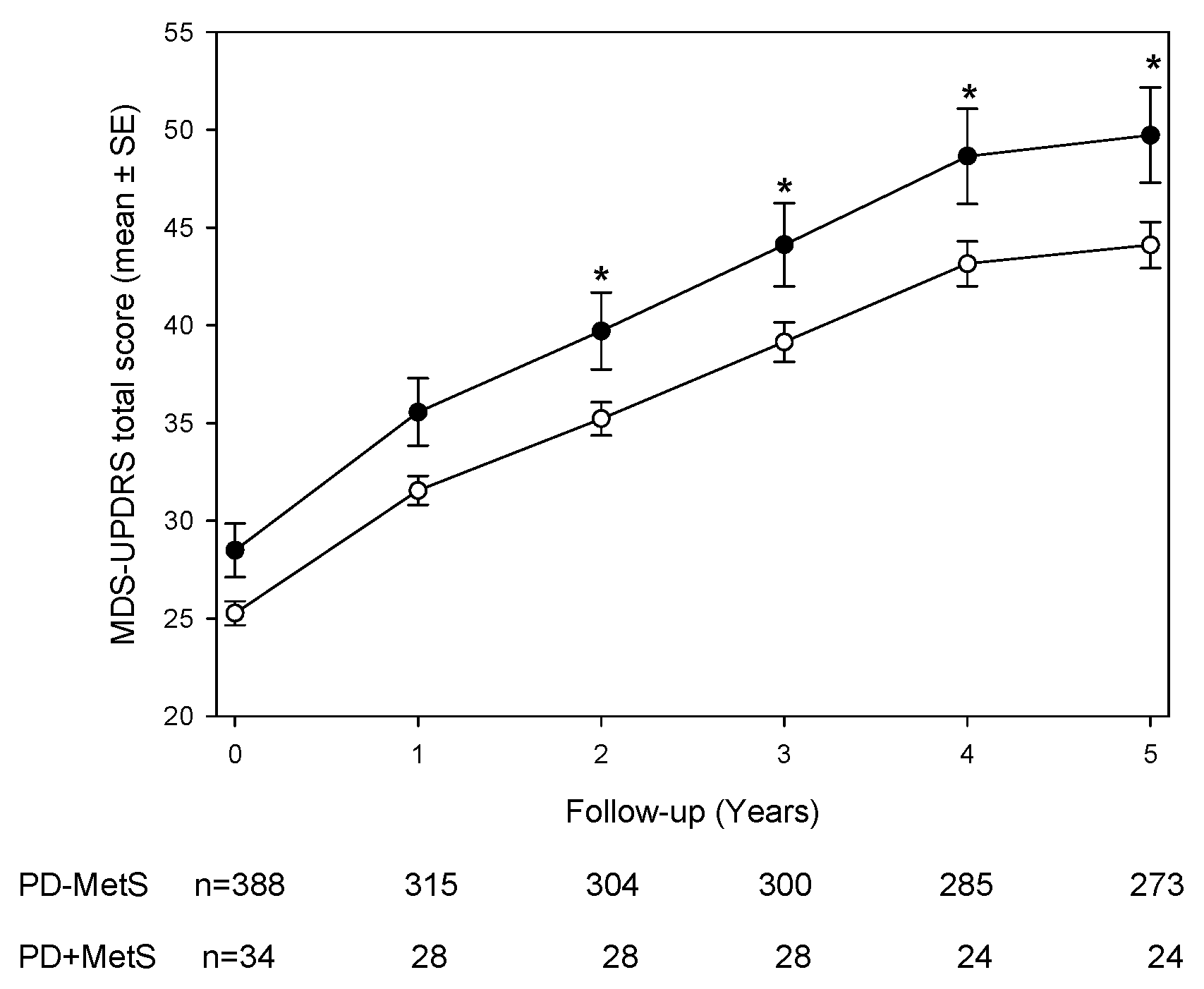

3.2. Longitudinal MDS-UPDRS Scores and Subscales

Figure 1 illustrates the longitudinal course of MDS-UPDRS total scores over five years. Both groups showed progressive increases in motor scores, but PD+MetS patients consistently exhibited higher scores at each annual visit. The overall group difference was highly significant (p<0.01 by generalized estimating equation [GEE] analysis). After adjusting for age, sex, and antiparkinsonian treatment, a GEE model with a MetS-by-time interaction revealed that the PD+MetS group had significantly higher MDS-UPDRS total scores than the PD-MetS group during years 2 through 5 (post-hoc p<0.05 for each of these timepoints). In contrast, at baseline and year 1, the between-group difference did not reach statistical significance (

Figure 1). Subscale analyses of the MDS-UPDRS (

Table 2) showed that differences were confined to specific domains. Non-motor aspects (Part I) and motor complications (Part IV) scores did not differ significantly between PD+MetS and PD-MetS at any time point (all p>0.05). Motor aspects of daily living (Part II) were significantly worse in the MetS group at early visits: mean Part II scores were higher in PD+MetS at baseline (7.1 ± 4.7 vs. 5.8 ± 4.1; p<0.01) and year 1 (9.4 ± 4.5 vs. 7.2 ± 5.0; p<0.05), but this gap narrowed in subsequent years. The most consistent differences were observed in the motor examination subscore (Part III). PD+MetS patients had higher Part III scores at every visit. For example, at baseline the mean Part III score was 23.6 ± 7.2 in the MetS group versus 20.7 ± 9.0 in the non-MetS group (p<0.01), and elevated scores persisted through year 5 (mean 35.7 ± 9.5 vs. 29.9 ± 13.6; p<0.05) (

Table 2). These findings indicate that patients with MetS experienced consistently worse motor function in time.

3.3. Genetic Association Analysis

Genetic analyses were performed in the 409 patients with complete genotype data (376 PD–MetS, 33 PD+MetS;

Table 3). Three Parkinson’s-associated SNPs showed significant frequency differences by MetS status. The ZNF646.KAT8.BCKDK_rs14235 variant was significantly overrepresented in PD+MetS: 30.3% of MetS patients were homozygous for the risk allele compared to 15.6% of non-MetS patients (recessive model OR 3.06, 95% CI 1.24–7.29; p=0.012). In contrast, risk alleles of NUCKS1_rs823118 and CTSB_rs1293298 were underrepresented in the MetS group. For NUCKS1_rs823118, only 6.1% of MetS patients carried two risk alleles versus 18.8% of non-MetS patients (OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.03–0.77; p=0.043). Similarly, carriage of at least one CTSB_rs1293298 risk allele was less common in PD+MetS (21.2% vs. 43.8%; OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.13–0.84; p=0.025). No significant differences were observed for other tested variants (e.g. GBA_N370S, COMT_rs4633). These genotype-phenotype associations (

Table 3) suggest that specific genetic factors may influence the likelihood of developing metabolic syndrome in PD.

The Akaike Information Coefficient (AIC) was used to compare the additive, dominant, and recessive models. The one with the lowest AIC was selected for the multivariate model provided p-value was <0.15.

4. Discussion

The PPMI is a cohort study involving patients from all around the world. Patients are included immediately after being diagnosed with PD and are followed for at least 5 years. Patients are assessed by certified instruments in a standardized manner. Therefore, our findings of more severe motor symptoms in PD patients with MetS are robust and might be extensive to patients outside the study.

Recent studies suggest that MetS increases the risk of PD. Indeed, in a Korean study involving more than 17 million people, MetS significantly increased the lifetime risk of suffering from PD by 24% [

12]. In the same database, Roh et al. showed that PD risk increased with the number of MetS components [

13]. Interestingly, high blood pressure, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and high fasting blood glucose significantly increased PD incidence by 20-34%, while elevated waist circumference was not associated with PD incidence. Furthermore, high triglycerides exerted a protective effect against PD incidence, especially in men. Their results have been confirmed by other studies, including a recent meta-analysis involving over 23 million participants’ data in 11 articles [

14].

The evidence about MetS’s impact on PD severity is less abundant. Ninety-nine PD patients from Mexico — 8% having MetS — showed differences in the gastrointestinal, mood/apathy, sexual function, perceptual, and miscellaneous sections of the Non-Motor Symptoms Scale [

15]. No differences were found in cognition, motor symptoms, or life quality. However, a years-long study of 787 Chinese PD patients suggested MetS increased cognitive deterioration risk [

16]. In a large US study, PD patients with MetS showed a substantially higher annual increase in total UPDRS and motor UPDRS scores compared to their counterparts without MetS [

17]. Similar results were observed in a study on 1563 patients with mild Parkinsonian symptoms who completed a 6-year follow-up [

18]. Our results, in agreement with these reports and the bulk of evidence, foster us to hypothesize that MetS may impair dopaminergic neurotransmission in the substantia nigra.

MetS shares some pathophysiological traits with PD, including insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and inflammatory responses [

19]. Insulin resistance stimulates adipose tissue growth, hence pro-inflammatory adipokine secretion. A similar process has been suggested to occur in the brain. Chronic low-grade inflammation is associated with increased systemic oxidative stress inside and outside the brain. Neuroinflammation may cause reductions in neurotrophic factors, leading to neurodegeneration. Exenatide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist used in Diabetes Mellitus Type 2, has shown promising results for motor symptoms in PD clinical trials [

20]. These results emphasize the importance of insulin resistance in the genesis of motor dysfunction in PD. Extracellular vesicles produced in the adipose tissue can cross the brain-blood barrier and contribute to neuroinflammation in MetS [

21]. Candesartan inhibition of their proinflammatory effects [

22] stresses the importance of tissue Renin-Angiotensin Systems intertwined in metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases [

23,

24]. Several pieces of evidence suggest that Heat Shock Proteins (Hsp) might represent a link between PD and MetS as well [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Finally, Insulin/IGF1, TOR, AMPK, and sirtuin pathways have been involved in proteostasis control [

29] and might also provide a link between MetS and PD [

30,

31,

32,

33,34,35].

The genetic traits connecting MetS and PD remain unknown. In our study, we compared the frequency of the 72 SNPs known to modify the risk of PD [

13] among patients with or without MetS. We observed that MetS was associated with a higher frequency of the ZNF646.KAT8.BCKDK_rs14235 variant and a lower frequency of the variants NUCKS1_rs823118 and CTSB_rs1293298. BCKDK gen codifies a branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase, which participates in lipids metabolism, and its mutation has been associated with multiple diseases including cancer, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [36], neurodevelopmental disorders, heart failure, and PD [

13]. The BCKDK_rs14235 variant is associated with differential expressions of multiple genes in brain tissue, including KAT8, ZNF646, VKORC1, and BCKDK. Interestingly, the CTSB, ZNF646 and KAT8 genes have been associated with obesity [36,37]. The BCKDK_rs14235 variant increases the risk of PD, perhaps by modifying KAT8 gene expression, involved in modulating autophagic flux [38].

NUCKS1 function has been related to chromatin architecture and transcription modulation, DNA repair and cell cycle regulation [

29]. This gene is largely expressed in stem cells and the brain. It has been associated with several diverse malignancies in humans, including cancer, MetS and PD [

29]. The NUCKS1 protein is a nuclear protein that binds to DNA and nucleosomes and induces structural changes within chromatin [

30]. Therefore, NUCKS1 is a multifaceted protein that regulates several biological processes and signal transduction pathways.

The CTSB encodes a member of the C1 family of peptidases. Alternative splicing generated the cathepsin B protein, a lysosomal cysteine protease with both endopeptidase and exopeptidase activity that may play a role in protein turnover [

31]. Cathepsin B has been implicated both in the lysosomal degradation of α-synuclein [

32] and as a genetic risk factor for PD [

10]. In obese patients, white adipose tissue accumulation causes adipocyte hypertrophy and cathepsin B release [

33]. Cathepsin B leads to autophagy in adipocytes, inflammation and macrophage infiltration, therefore contributing to metabolic syndrome [

33].

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the observational nature of the PPMI study prevents any causal inference between metabolic syndrome and Parkinson’s disease progression. Second, MetS status was assessed only at baseline, and potential changes in metabolic parameters during follow-up were not considered. Third, the relatively small number of patients with MetS may have limited the statistical power for some genetic and clinical comparisons. Additionally, although multiple covariates were adjusted for, the influence of residual or unmeasured confounders cannot be excluded. Lastly, as this study was based on a well-characterized research cohort, generalizability to broader or more diverse populations may be limited.

Our findings suggest a shared genetic background between Parkinson’s disease (PD) and metabolic syndrome (MetS), supporting the hypothesis that metabolic alterations may influence the course of PD. Given the association with more severe motor symptoms, MetS may represent a relevant modifier of disease expression. These results underscore the importance of early identification and close clinical monitoring of PD patients with MetS, and point to the need for further studies to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights a significant clinical and genetic link between metabolic syndrome (MetS) and Parkinson’s disease (PD). We demonstrated that PD patients with comorbid MetS present more severe motor symptoms throughout the disease course, with consistently higher MDS-UPDRS Part III scores over a 5-year follow-up. These findings suggest MetS acts as a disease modifier, accelerating motor deterioration in PD.

At the genetic level, our analysis revealed differential frequencies of specific SNPs in patients with and without MetS. The increased presence of the ZNF646.KAT8.BCKDK_rs14235 variant in MetS patients suggests a potential role for genes involved in lipid metabolism and autophagic regulation in the interplay between metabolic and neurodegenerative processes. Conversely, the decreased frequency of NUCKS1_rs823118 and CTSB_rs1293298 variants in MetS patients points to the possible protective role of pathways related to chromatin structure regulation and lysosomal protein turnover.

Taken together, these results support the hypothesis of a shared molecular basis between PD and MetS, with overlapping pathogenic mechanisms such as insulin resistance, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and impaired proteostasis. Importantly, our findings underscore the clinical relevance of identifying MetS in PD patients at an early stage, as it may inform prognosis and help guide more personalized monitoring and therapeutic strategies.

Future studies with larger and more diverse cohorts are warranted to confirm these associations and to explore whether metabolic interventions could mitigate PD progression in patients with coexisting MetS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.U and S.PLL; methodology, G.C., S.B.; statistical analysis, L.U., S.PLL; original manuscript: L.U., S.B., G.C., H.B. S.PLL; writing, review and editing, visualization, M.O-L, F.C.; supervision; S.PLL. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding sources for the study: The PPMI — a public-private partnership — is funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and funding partners, including Abbvie, Allergan, Amathus therapeutics, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Biogen Idec, BioLegend, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Calico, Celgene, Denali, Eli Lilly & Co., F. Hoffman-La Roche, Ltd., GE Healthcare, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Golub Capital, Handl Therapeutics, Insitro, Janssen, Lundbeck, Merck, Meso Scale, Neurocrine, Piramal, Pfizer, Prevail Therapeutics, Servier. TEVA, Takeda, Sanofi Genzyme, UCB, verily, and Voyager Therapeutics. This study was also partially funded by from the Agencia de Promoción Científica y Técnica (grant PICT-2020-SERIEA-01926).

Institutional Review Board Statement

We used a public database that was fully de-identified. Therefore, this approval was not necessary.

Informed Consent Statement

Not required for this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) database (

www.ppmi-info.org/data (accessed on 10 November 2020)). For up-to-date information on the study, visit

www.ppmi-info.org.

Acknowledgments

Data used in this article were obtained from the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) database (

www.ppmi-info.org/data). For up-to-date information on the study, visit

www.ppmi-info.org.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kalia, L.V.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson's disease, Lancet 2015, 386(9996) 896-912.

- Schapira, A.H.V. ; Chaudhuri, K.R. ; Jenner, P.; Non-motor features of Parkinson disease, Nat Rev Neurosci 2017, 18(7), 435-450. [CrossRef]

- Lang, A.E.; Espay, A.J., Disease Modification in Parkinson's Disease: Current Approaches, Challenges, and Future Considerations, Mov Disord 2018, 33(5) 660-677. [CrossRef]

- Otero-Losada, M. ; Cao, G. ; Gómez Llambí, H. ; Nobile, M.H. ; Azzato, F. ; Milei, J., Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Experimental Metabolic Syndrome, in: Biochemistry of Oxidative Stress. Physiopathology and Clinical Aspects, Gelpi, R.J.; Boveris, A. ; Poderoso J.J. (Eds.), Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2016, pp. 375-390.

- The Parkinson Progression Marker Initiative, The Parkinson Progression Marker Initiative (PPMI), Prog Neurobiol 2010, 95(4)629-35.

- Goetz, C.G.; Tilley, B.C.; Shaftman, S.R.; Stebbins, G.T.; Fahn, S.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Poewe, W.; Sampaio, C.; Stern, M.B.; Dodel, R.; Dubois, B.; Holloway, R.; Jankovic, J.; Kulisevsky, J.; Lang, A.E.; Lees, A.; Leurgans, S.; LeWitt, P.A.; Nyenhuis, D.; Olanow, C.W.; Rascol, O.; Schrag, A.; Teresi, J.A.; van Hilten, J.J.; LaPelle, N. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov Disord 2008, 23, 2129–2170. [CrossRef]

- Grundy, S.M.; Brewer, H.B., Jr.; Cleeman, J.I.; Smith, S.C., Jr.; Lenfant, C. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation 2004, 109, 433–438.

- Chevalier, G.; Udovin, L.; Otero-Losada, M.; Bordet, S.; Capani, F.; Luo, S.; Goetz, C.G.; Perez-Lloret, S. Genetics of neurogenic orthostatic hypotension in Parkinson's disease: Results from a cross-sectional in silico study. Brain Sci 2023, 13, Article 3. [CrossRef]

- Parkinson Progression Marker Initiative. The Parkinson Progression Marker Initiative (PPMI). Prog Neurobiol 2011, 95, 629–635.

- Nalls, M.A.; Blauwendraat, C.; Vallerga, C.L.; Heilbron, K.; Bandres-Ciga, S.; Chang, D.; Tan, M.; Kia, D.A.; Noyce, A.J.; Xue, A.; Bras, J.; Young, E.; von Coelln, R.; Simón-Sánchez, J.; Schulte, C.; Sharma, M.; Krohn, L.; Pihlstrøm, L.; Siitonen, A.; Iwaki, H.; Leonard, H.; Faghri, F.; Gibbs, J.R.; Hernandez, D.G.; Scholz, S.W.; Botia, J.A.; Martinez, M.; Corvol, J.C.; Lesage, S.; Jankovic, J.; Shulman, L.M.; Sutherland, M.; Tienari, P.; Majamaa, K.; Toft, M.; Andreassen, O.A.; Bangale, T.; Brice, A.; Yang, J.; Gan-Or, Z.; Gasser, T.; Heutink, P.; Shulman, J.M.; Wood, N.W.; Hinds, D.A.; Hardy, J.A.; Morris, H.R.; Gratten, J.; Visscher, P.M.; Graham, R.R.; Singleton, A.B. Identification of novel risk loci, causal insights, and heritable risk for Parkinson's disease: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Lancet Neurol 2019, 18, 1091–1102. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. Generalized estimating equations in longitudinal data analysis: A review and recent developments. Adv Stat 2014, 2014, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Nam, G.E.; Kim, S.M.; Han, K.; Kim, N.H.; Chung, H.S.; Kim, J.W.; Han, B.; Cho, S.J.; Yu, J.H.; Park, Y.G.; Choi, K.M. Metabolic syndrome and risk of Parkinson disease: A nationwide cohort study. PLoS Med 2018, 15, e1002640. [CrossRef]

- Roh, J.H.; Lee, S.; Yoon, J.H. Metabolic syndrome and Parkinson's disease incidence: A nationwide study using propensity score matching. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2021, 19, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.; Barros, W.M.A.; Silva, J.M.L.; Silva, M.R.M.; Silva, A.B.J.; Fernandes, M.S.S.; Santos, M.; Silva, M.L.D.; Carmo, T.S.D.; Silva, R.K.P.; Silva, K.G.D.; Souza, S.L.; Souza, V.O.N. Effect of metabolic syndrome on Parkinson's disease: A systematic review. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2021, 76, e3379. [CrossRef]

- Meléndez-Flores, J.D.; Castillo-Torres, S.A.; Cerda-Contreras, C.; Chávez-Luévanos, B.; Estrada-Bellmann, I. Clinical features of metabolic syndrome in patients with Parkinson's disease. Rev Neurol 2021, 72, 9–15.

- Peng, Z.; Dong, S.; Tao, Y.; Huo, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, W.; Qu, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, H. Metabolic syndrome contributes to cognitive impairment in patients with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2018, 55, 68–74. [CrossRef]

- Leehey, M.; Luo, S.; Sharma, S.; Wills, A.A.; Bainbridge, J.L.; Wong, P.S.; Simon, D.K.; Schneider, J.; Zhang, Y.; Perez, A.; Dhall, R.; Christine, C.W.; Singer, C.; Cambi, F.; Boyd, J.T. Association of metabolic syndrome and change in Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale scores. Neurology 2017, 89, 1789–1794. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Zhou, R.; Liu, D.; Cui, M.; Yu, K.; Yang, H.; Li, L.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Hong, W.; Huang, J.; Wang, C.; Ma, J.; Zhou, H. Association between metabolic syndrome and mild parkinsonian signs progression in the elderly. Front Aging Neurosci 2021, 13, 722836. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.Y.; Liu, S.F.; Zhuang, J.L.; Li, M.M.; Huang, Z.P.; Chen, Y.H.; Chen, X.R.; Chen, C.N.; Lin, S.; Ye, L.C. Recent research progress on metabolic syndrome and risk of Parkinson's disease. Rev Neurosci 2023, 34, 719–735. [CrossRef]

- Athauda, D.; Maclagan, K.; Skene, S.S.; Bajwa-Joseph, M.; Letchford, D.; Chowdhury, K.; Hibbert, S.; Budnik, N.; Zampedri, L.; Dickson, J.; Li, Y.; Aviles-Olmos, I.; Warner, T.T.; Limousin, P.; Lees, A.J.; Greig, N.H.; Tebbs, S.; Foltynie, T. Exenatide once weekly versus placebo in Parkinson's disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 1664–1675. [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, J.C. Extracellular vesicles, from the pathogenesis to the therapy of neurodegenerative diseases. Transl Neurodegener 2022, 11, 53. [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, M.A.; Labandeira, C.M.; Lago-Baameiro, N.; Valenzuela, R.; Pardo, M.; Labandeira-Garcia, J.L.; Rodriguez-Perez, A.I. Extracellular vesicles and their renin-angiotensin cargo as a link between metabolic syndrome and Parkinson's disease. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12, 12. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Lloret, S.; Otero-Losada, M.; Toblli, J.E.; Capani, F. Renin-angiotensin system as a potential target for new therapeutic approaches in Parkinson's disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2017, 26, 1163–1173. [CrossRef]

- de Kloet, A.D.; Krause, E.G.; Woods, S.C. The renin angiotensin system and the metabolic syndrome. Physiol Behav 2010, 100, 525–534. [CrossRef]

- Auluck, P.K.; Chan, H.Y.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M.; Bonini, N.M. Chaperone suppression of alpha-synuclein toxicity in a Drosophila model for Parkinson's disease. Science 2002, 295, 865–868. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Wolfer, D.P.; Lipp, H.P.; Büeler, H. Hsp70 gene transfer by adeno-associated virus inhibits MPTP-induced nigrostriatal degeneration in the mouse model of Parkinson disease. Mol Ther 2005, 11, 80–88. [CrossRef]

- Klucken, J.; Shin, Y.; Masliah, E.; Hyman, B.T.; McLean, P.J. Hsp70 reduces alpha-synuclein aggregation and toxicity. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 25497–25502.

- Roodveldt, C.; Bertoncini, C.W.; Andersson, A.; van der Goot, A.T.; Hsu, S.T.; Fernández-Montesinos, R.; de Jong, J.; van Ham, T.J.; Nollen, E.A.; Pozo, D.; Christodoulou, J.; Dobson, C.M. Chaperone proteostasis in Parkinson's disease: stabilization of the Hsp70/alpha-synuclein complex by Hip. EMBO J 2009, 28, 3758–3770.

- Østvold, A.C.; Grundt, K.; Wiese, C. NUCKS1 is a highly modified, chromatin-associated protein involved in a diverse set of biological and pathophysiological processes. Biochem J 2022, 479, 1205–1220. [CrossRef]

- Hock, R.; Furusawa, T.; Ueda, T.; Bustin, M. HMG chromosomal proteins in development and disease. Trends Cell Biol 2007, 17, 72–79. [CrossRef]

- Stoka, V.; Turk, V.; Turk, B. Lysosomal cathepsins and their regulation in aging and neurodegeneration. Ageing Res Rev 2016, 32, 22–37. [CrossRef]

- Drobny, A.; Boros, F.A.; Balta, D.; Prieto Huarcaya, S.; Caylioglu, D.; Qazi, N.; Vandrey, J.; Schneider, Y.; Dobert, J.P.; Pitcairn, C.; Mazzulli, J.R.; Zunke, F. Reciprocal effects of alpha-synuclein aggregation and lysosomal homeostasis in synucleinopathy models. Transl Neurodegener 2023, 12, 31. [CrossRef]

- Araujo, T.F.; Cordeiro, A.V.; Vasconcelos, D.A.A.; Vitzel, K.F.; Silva, V.R.R. The role of cathepsin B in autophagy during obesity: A systematic review. Life Sci 2018, 209, 274–281. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).