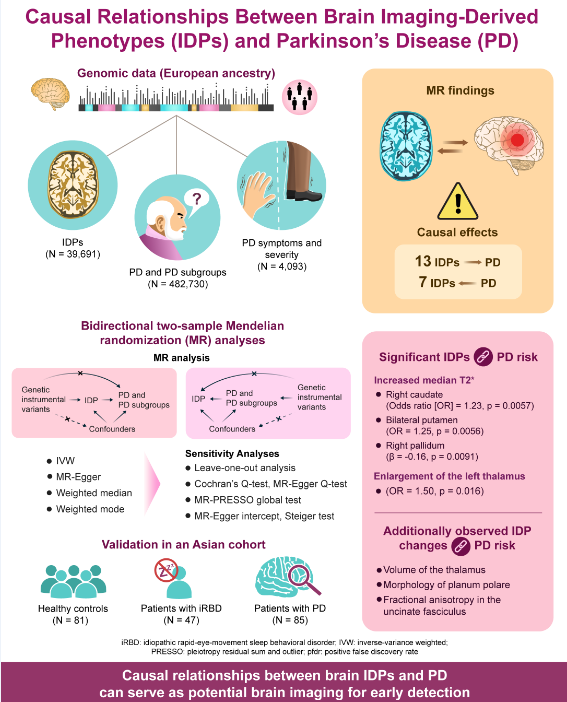

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder globally, imposing a significant health and economic burden on the society. Despite extensive research, the pathogenesis of PD remains unclear, and no effective causative treatments exist. Owing to its insidious onset and prolonged clinical latency, opportunities for early neuroprotection are often missed by the time motor symptoms emerge. Therefore, identifying early diagnostic biomarkers and exploring the underlying mechanisms of PD are crucial.

Brain imaging, a non-invasive method, is essential for detecting PD at various stages by revealing changes in brain structure, connectivity, and function. Observational studies have linked brain imaging-derived phenotypes (IDPs) to PD. For example, susceptibility-weighted imaging shows reduced high signals in the dorsal lateral substantia nigra (nigrosome 1) in patients with PD [

1], aiding in the conversion from idiopathic rapid-eye-movement sleep behaviour disorder (iRBD) to PD [

2]. Diffusion-weighted imaging also reveals altered connections among the substantia nigra, thalamus, and striatum in PD [

3]. Additionally, changes in brain region volumes and functional connectivity distinguish healthy individuals from patients with PD and different PD symptoms. Although these findings suggest a strong link between brain imaging findings and PD, observational studies may involve confounding factors and cannot clarify whether imaging features precede or follow PD onset. Therefore, investigating the causal role of IDPs in PD, and vice versa, is essential.

Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis, comparable to a naturally occurring randomized controlled trial, randomly allocates alleles during gametogenesis, making it useful for assessing causal relationships between exposure and outcome. By using single nucleotide polymorphisms as instrumental variables, MR controls confounding factors and avoids reverse causality. In 2023, Zhu et al. used MR to study the link among three white matter lesions (i.e., white matter hyperintensities, fractional anisotropy, and mean diffusivity) and PD risk [

4]. Yu et al. also recently used MR to explore the association between brain structure and PD risk [

5]. However, these studies focused on structural changes and lacked data on connectivity and function. Furthermore, they did not examine causal links between IDPs and PD symptoms or severity. Therefore, a comprehensive analysis of multimodal brain imaging and its relationship with PD, motor/non-motor symptoms, and severity is needed. Understanding these causal relationships may uncover PD pathogenesis, early biomarkers, and targets for prevention.

Thus, this study aimed to examine the causal relationship between brain IDPs and PD. Towards this goal, we performed bidirectional two-sample MR to explore causal associations between 3,370 IDPs (n=39,691) and PD (n=482,730), along with PD symptoms and severity (n=4,093) [

6,

7,

8]. The findings were then validated in an Asian PD cohort to determine if results from European patients applied to Asians. Additionally, patients with iRBD confirmed by video-polysomnography were included to support our MR findings, helping in our investigation of the causal role of IDPs in PD and the identification of neuroimaging changes that preceded PD onset.

4. Discussion

The current study identified 13 IDPs with significant evidence of potential causal effects on PD, as well as potential causal effects of PD on 7 IDPs. Additionally, validation in an Asian cohort (HCs, iRBD, and PD) yielded consistent findings, offering valuable insights into PD pathogenesis and early diagnostic strategies and paving the way for advancements in disease management and prognosis. To our best knowledge, this is the first MR analysis investigating causal connections between multi-modal imaging (brain structure, connectivity, and function) and PD, including PD motor/non-motor symptoms and disease severity.

In the MR analysis, we identified susceptibility-weighted imaging features associated with increased PD risk. Susceptibility-weighted imaging measures brain tissue magnetic susceptibility, primarily influenced by iron. In the UK Biobank IDP GWAS, median T2star values were analyzed in 14 major subcortical grey matter structures, where elevated T2star levels indicated reduced iron deposition. The results demonstrated that higher T2star in the caudate and putamen were causally linked to increased PD risk, whereas lower T2star values correlated with higher H-Y scores. This suggests that reduced iron deposition in these regions may increase PD susceptibility, whereas higher iron accumulation could exacerbate PD severity. This supports the growing interest in iron deposition as a key factor in PD pathogenesis [

9]. Extensive evidence indicates that during the progression of PD, iron is specifically alternated in various brain regions, notably the substantia nigra (SN). Furthermore, the dysregulation of iron causes ferritinophagy and lipid peroxidation to induce ferroptosis in PD, a form of cell death reliant on iron. According to the distinctive patterns of iron accumulation in specific brain regions, extensive studies have confirmed that imaging can potentially diagnose PD in its early stages. The current findings were consistent with those of another MR study that reported increased T2star as potentially causally associated with heightened PD risk [

10]. However, that study incorrectly interpreted that increased iron levels were causally linked to PD. Furthermore, the study focused on changes in SWI and lacked data on connectivity and function. Although several observational studies have reported higher iron deposition in the SN, findings regarding iron accumulation in the striatum of patients with PD have been less consistent [

11,

12].

Furthermore, they did not examine causal links between IDPs and PD symptoms or severity. We propose that iron deposition in the striatum undergoes dynamic changes at different PD stages. Given that iRBD is considered a prodromal phase of PD, we examined striatum T2star values in HC, participants with iRBD, and participants with PD. The results showed increased T2star values in the caudate, putamen, and pallidum in participants with iRBD, whereas T2star values were decreased in participants with PD. This suggests a stage where iron deposition in the striatum initially decreases and then increases during PD progression. In the classic model of PD circuitry, dopaminergic projections originate from the SN and extend to the caudate, putamen, and pallidum [

13]. We propose that an initial redistribution of iron occurs during the early degeneration of dopaminergic neurons, leading to increased iron in the perinuclear region of the SN (cell body) and decreased iron in the axons of the caudate and putamen (projections). As the disease progresses, iron overload spreads across all cellular compartments, leading to increased iron levels in both the SN and striatum. Interestingly, two studies support our hypothesis. Using subcellular quantification, Lashuel et al. found decreased iron levels in neurites and distal ends of neurons, whereas they were increased in cell bodies in PD models [

14]. Similarly, Ortega et al. overexpressed α-synuclein in PC12 cells to model PD and observed iron redistribution with accumulation in the perinuclear region [

15]. Future studies are needed to verify iron redistribution during different PD stages and explore the underlying mechanisms.

Regarding T1 imaging analyses in the MR study, the current study observed that an enlarged left thalamus volume was a potential causal risk factor for PD. The observational study showed progressive thalamic enlargement from HCs to patients with iRBD and PD. However, findings regarding whole thalamus morphology have varied. One study reported thalamic atrophy in PD [

16], while others found no significant differences [

17,

18]. More recent studies have confirmed thalamic enlargement in PD [

19,

20,

21], with evidence of progressive volume increase as the disease advances [

21]. Additionally, increased thickness and more expansive surface areas have been observed in PD, consistent with increased volumes [

19,

20]. However, the causative mechanisms remain unclear. We propose that compensatory mechanisms might explain these results. As a key node in the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuit, the thalamus plays a crucial role in transferring motor, associative, and limbic signals between the cortex and subcortical nuclei [

13]. Thus, thalamic enlargement could reflect adaptive compensatory responses, possibly to maintain or enhance neural function in response to underlying pathology.

Furthermore, the thalamus participates in the cerebello-thalamo-cortical loop, which may compensate for degeneration in the nigrostriatal system [

22]. Early thalamic hypertrophy may result from hyperactivity in the cerebellothalamic circuit, particularly linked to Parkinson’s tremor. Another interesting finding in our MR study is that elevated mean intracellular volume fraction in the splenium of corpus callosum (CC) might have a causal relationship with PD-related depression. CC is the most prominent white matter pathway providing information transfer between the two hemispheres. The splenium connects association areas of the parietal and temporal lobes (anterior splenium) and occipital lobes (posterior splenium). Observational studies have illustrated a greater FA in the splenium of CC in patients with major depression disorder than in that of healthy controls, and they further identified a positive correlation between FA values in splenium of CC and anxiety, one of the three core symptoms (anhedonia, anxiety, and psychomotor retardation) involved in depression [

23].

In MR analysis to determine whether PD was a causal factor for IDPs, PD was found to be possibly contribute to lower mean FA in the left UF and decreased surface area of the left planum polare. The UF is a key tract connecting the inferior frontal gyrus and the anterior temporal lobe regions. Several researchers observed widespread demyelination and degeneration of the UF in patients with PD [

24,

25,

26,

27]. These structural changes in the UF could potentially account for the presence of depressive symptoms and anxiety commonly observed in individuals with PD. Our findings highlighted the significant influence of PD on sensory alterations, with a reduced surface area in the left planum polare of the superior temporal gyrus, associated with the primary auditory cortex [

28,

29]. These findings shed light on the potential underlying mechanisms linking PD pathology to both emotional disturbances and sensorimotor alterations.

Given the large heterogeneity in thalamic subnuclei function, we further assessed structural thalamic morphology by subnuclei. In the MR study, Pt and VPL emerged as two predominant subregions. This was corroborated by findings in the observational cohort analysis, showing progressive volume increases from HCs to iRBD and finally to PD. Our findings are consistent with previous observational findings of enlargement of these subregions [

19,

20]. The Pt is part of the medial nuclear group, with stronger projections to subcortical areas (hypothalamus, amygdala, brainstem, hippocampus) than to cortical areas (prefrontal, insular, and orbital cortex). It also plays a key role in regulating wakefulness. Enlargement of the Pt may contribute to sleep disorders such as insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness in patients with PD. The VPL processes somatosensory, especially nociceptive information, and projects to the somatosensory and insular cortex. Enlargement of the VPL may explain sensory disturbances and pain in patients with PD.

This study presents compelling evidence that specific IDPs have causal relationships with PD and may serve as diagnostic or predictive biomarkers of its PD risk, severity, and symptoms. First, imaging biomarkers can be used in early risk identification for PD. The ROC analysis suggests that combined IDP markers improve diagnostic accuracy, with AUC up to 0.80 for early PD. Using a composite of biomarkers may be particularly useful in distinguishing HCs from PD or high-risk groups, such as iRBD patients. Second, imaging biomarkers can be used as prognostic indicators of PD progression and severity. The study found that increased median T2star values in the right pallidum was associated with lower disease severity, as indicated by a reduced H-Y score. Monitoring such IDPs over time in PD patients may offer a way to objectively track disease progression. Third, these imaging biomarkers help predicting and managing PD-related symptoms. Higher intracellular volume fraction in the splenium of CC was causally linked with an increased risk of depression in PD. This suggests that imaging biomarkers can guide interventions for mental health management in PD, particularly in those at higher risk for depression. Fourth, the findings can guide therapeutic approaches and treatment planning. For patients with specific biomarker profiles (e.g., those with larger thalamic volume), clinicians might tailor neuroprotective treatments. Meanwhile, those showing IDPs associated with severe PD or depression risk might receive closer monitoring or early psychiatric support. Fifth, IDP testing can serve as a tool in clinical research and trials. IDPs can be used as endpoints in clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy of neuroprotective drugs or other therapies. These biomarkers can serve as objective indicators of drug impact on PD risk or progression.

The strengths of the present study are substantial. First, the two-sample MR design minimized the potential for confounding factors and reverse causation, allowing us to explore underlying mechanisms and identify causal relationships between IDPs and PD. The large GWAS sample size reduced bias and increased statistical power. Second, the inclusion of comprehensive multi-modal neuroimaging data, along with detailed PD symptoms and severity, added depth to our findings. Third, validation in an Asian cohort broadened the generalizability of our results. We included patients with video-polysomnography-confirmed iRBD to better understand IDP changes in the prodromal stage of PD. Additionally, this study provided new insights into potential imaging biomarkers for predicting and diagnosing early PD. However, our study also had limitations. First, Winner’s curse bias can occur when the same GWAS data are used to select instrumental variables and estimate their association with the exposure. Avoiding Winner’s curse was balanced with minimizing precision loss due to smaller sample sizes [

30]. Moreover, although we performed sensitivity analyses, pleiotropy and heterogeneity could not be avoided in MR study. Second, selection bias was inevitable in both the UK Biobank Imaging cohort and PD cohorts. Further, the relatively small sample size of the observational cohort might have decreased the statistical power. Longitudinal studies are needed to validate our observations and explore the mechanisms underlying these relationships.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z., M.N., Y.L., B.W. and J.L.; methodology, Y.Z.; software, M.Z.; validation, M.Z. and Z.D.; formal analysis, Y.Z. M.Z. and X.W.; investigation, Z.Y., L.Z., Q.Y., and M.Z. ; resources, Z.Y., L.Z., and M.N.; data curation, Z.Y. and M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z. and M.N.; writing—review and editing, X.W and M.N.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, Z.Y., L.Z., and M.N.; funding acquisition, M.N. and J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Y.Z., M.Z., and Z.Y. contributed equally.

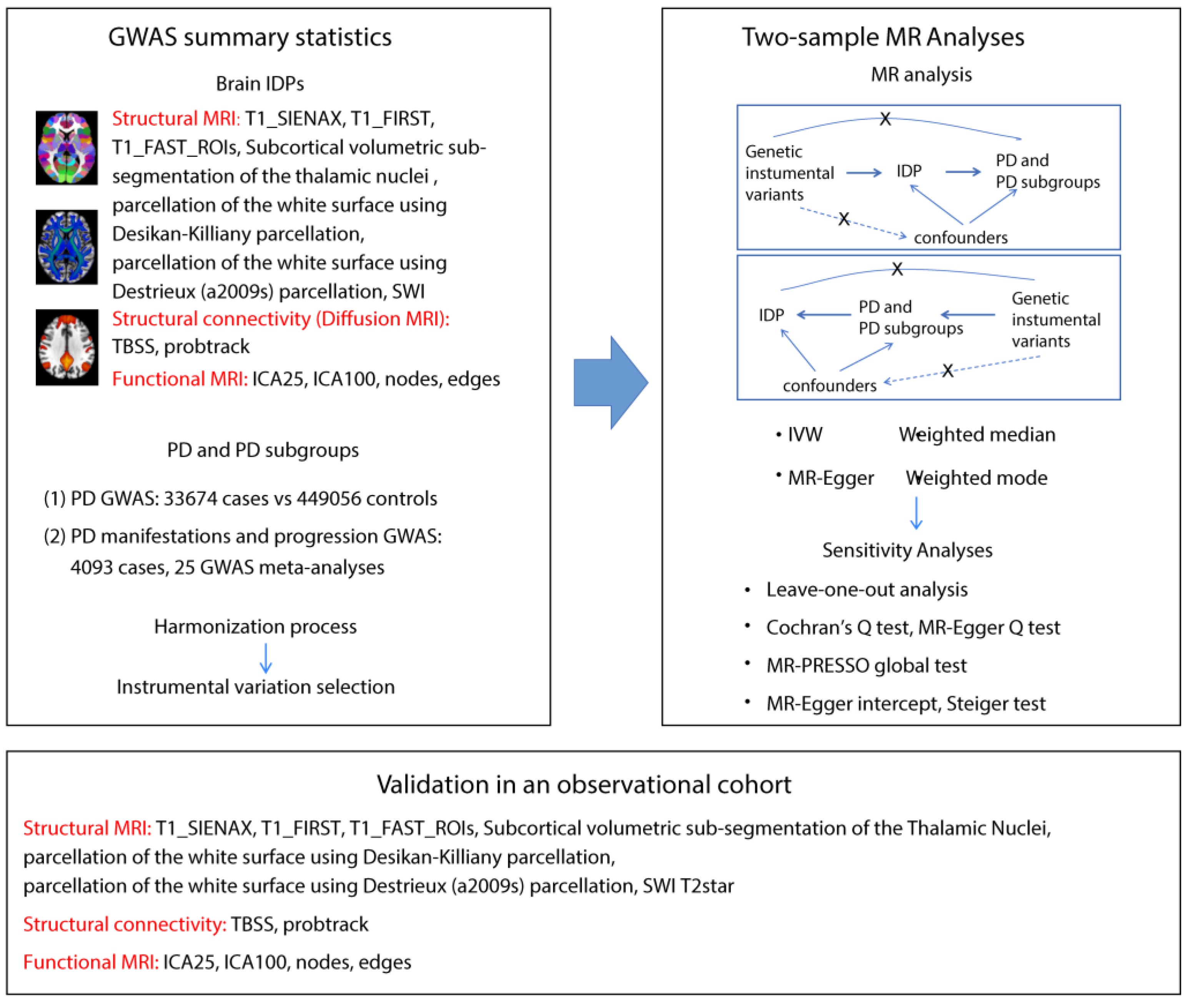

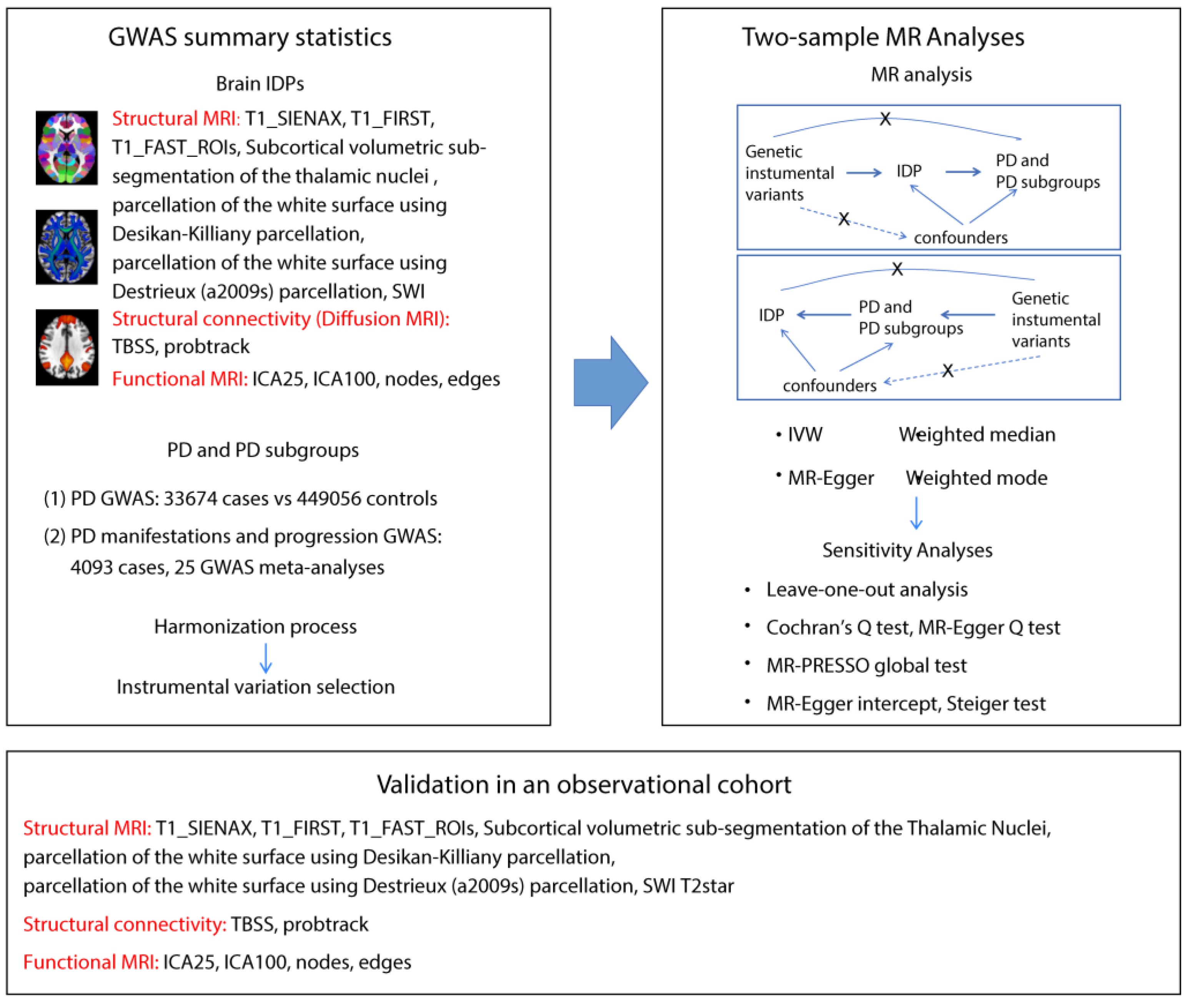

Figure 1.

Workflow of the causal inference between IDPs and PD. The diagram shows the Mendelian randomization and observational study to explore the causal relationships between IDPs and PD. The procedure entails the selection of specific SNPs from GWAS datasets, performing MR analysis, sensitivity analyses, and observational cohort analyses. Abbreviations: T1_SIENAX: T1-weighted imaging analysis using Structural Image Evaluation, using Normalization, of Atrophy: Cross-sectional; T1_FIRST: T1-weighted imaging analysis using FMRIB’s Integrated Registration and Segmentation Tool; T1_FAST_ROI: T1-weighted imaging gray matter segmentation using FMRIB’s Automated Segmentation Tool within 139 regions of interest; SWI: susceptibility-weighted imaging; TBSS: Tract-Based Spatial Statistics style analysis; probtrack: probabilistic tractography (with crossing fiber modelling) using PROBTRACKx; ICA: independent component analysis; SNPs: single nucleotide polymorphisms; IVW: inverse-variance weighted; MR-PRESSO: Mendelian randomization Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the causal inference between IDPs and PD. The diagram shows the Mendelian randomization and observational study to explore the causal relationships between IDPs and PD. The procedure entails the selection of specific SNPs from GWAS datasets, performing MR analysis, sensitivity analyses, and observational cohort analyses. Abbreviations: T1_SIENAX: T1-weighted imaging analysis using Structural Image Evaluation, using Normalization, of Atrophy: Cross-sectional; T1_FIRST: T1-weighted imaging analysis using FMRIB’s Integrated Registration and Segmentation Tool; T1_FAST_ROI: T1-weighted imaging gray matter segmentation using FMRIB’s Automated Segmentation Tool within 139 regions of interest; SWI: susceptibility-weighted imaging; TBSS: Tract-Based Spatial Statistics style analysis; probtrack: probabilistic tractography (with crossing fiber modelling) using PROBTRACKx; ICA: independent component analysis; SNPs: single nucleotide polymorphisms; IVW: inverse-variance weighted; MR-PRESSO: Mendelian randomization Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier.

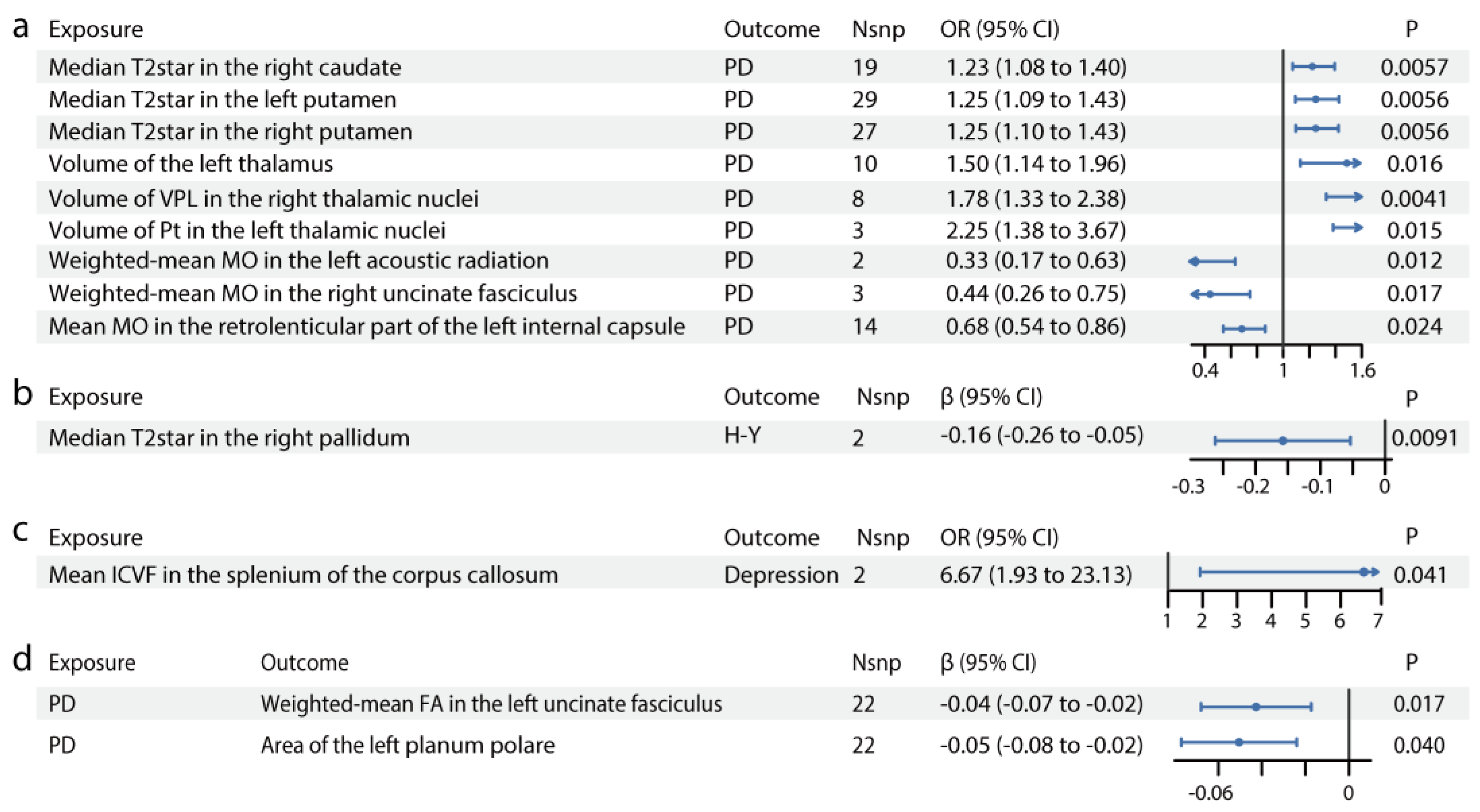

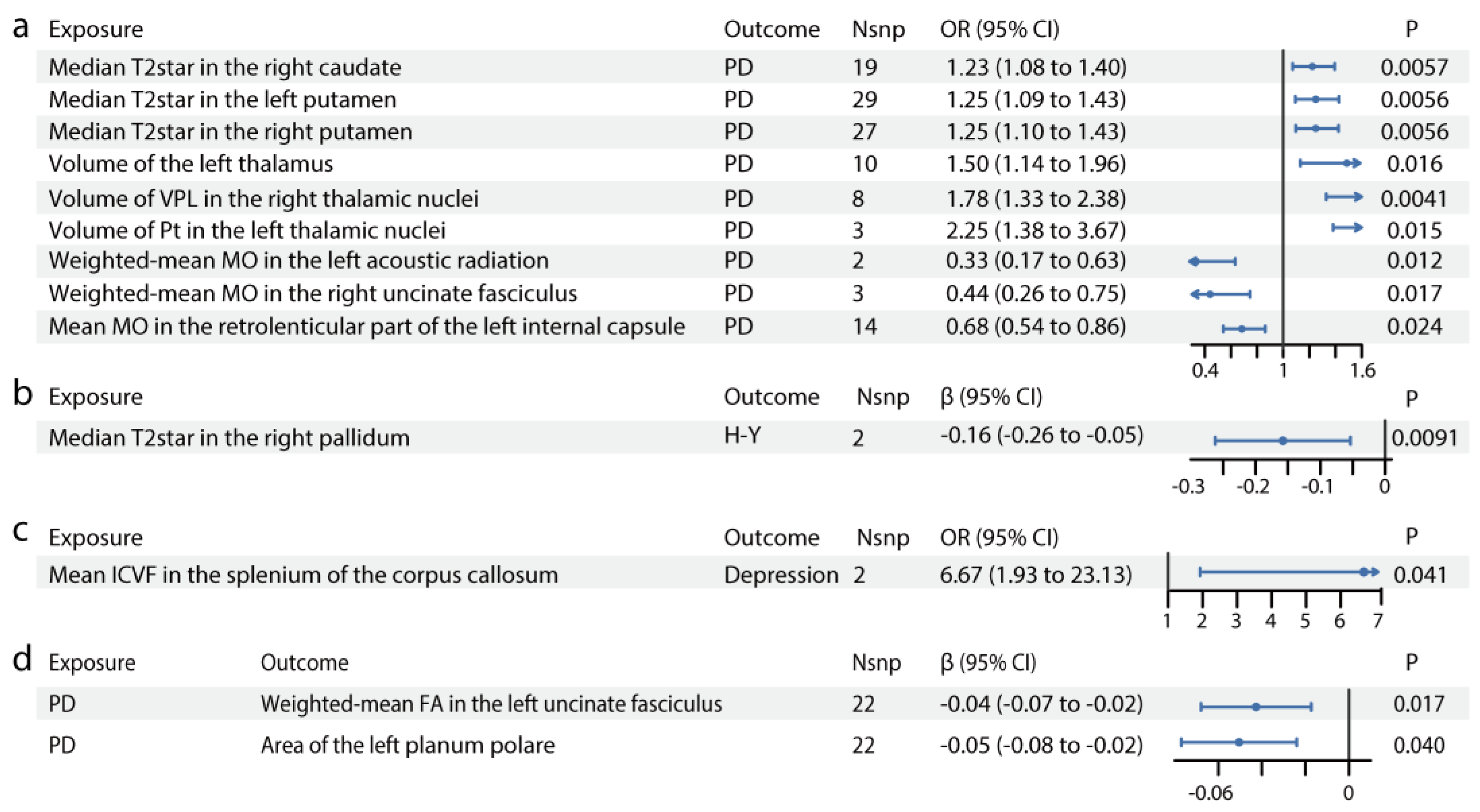

Figure 2.

Causal relationships between IDPs and PD. Forest plots show the significant causal effects of IDPs on PD (a), PD severity (b), and PD manifestations (c) with p<0.05. The forest plots demonstrate significant causal effects of alternations in median T2star in the striatum and volumes of the thalamus, as well as its subregions VPL and Pt on PD (a). Furthermore, the data suggest that altered median T2star in the pallidum might be causally associated with PD severity (b), while the mean ICVF in the splenium of the corpus callosum may be causally associated with PD depression (c). (d) Forest plots show significant causal effects of PD on IDPs. Data suggest PD might have causal effects on weighted-mean FA in the tract UF and area of the left planum polare. Each circle in the graph represents an inverse-variance weighted estimate. The horizontal line represents the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the estimates. For binomial outcomes, MR estimates are reported as odds ratios (ORs) along with their corresponding 95% Cls. For continuous outcomes, the MR estimates are reported as betas with their 95% CIs. Abbreviations: nsnp: number of SNPs; P: p value after Bonferroni and false discovery rate correction; H&Y: Hoehn-Yahr stage; VPL: ventral posterolateral nucleus; Pt: paratenial nucleus; MO: diffusion tensor mode; ICVF: intracellular volume fraction; FA: fractional anisotropy.

Figure 2.

Causal relationships between IDPs and PD. Forest plots show the significant causal effects of IDPs on PD (a), PD severity (b), and PD manifestations (c) with p<0.05. The forest plots demonstrate significant causal effects of alternations in median T2star in the striatum and volumes of the thalamus, as well as its subregions VPL and Pt on PD (a). Furthermore, the data suggest that altered median T2star in the pallidum might be causally associated with PD severity (b), while the mean ICVF in the splenium of the corpus callosum may be causally associated with PD depression (c). (d) Forest plots show significant causal effects of PD on IDPs. Data suggest PD might have causal effects on weighted-mean FA in the tract UF and area of the left planum polare. Each circle in the graph represents an inverse-variance weighted estimate. The horizontal line represents the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the estimates. For binomial outcomes, MR estimates are reported as odds ratios (ORs) along with their corresponding 95% Cls. For continuous outcomes, the MR estimates are reported as betas with their 95% CIs. Abbreviations: nsnp: number of SNPs; P: p value after Bonferroni and false discovery rate correction; H&Y: Hoehn-Yahr stage; VPL: ventral posterolateral nucleus; Pt: paratenial nucleus; MO: diffusion tensor mode; ICVF: intracellular volume fraction; FA: fractional anisotropy.

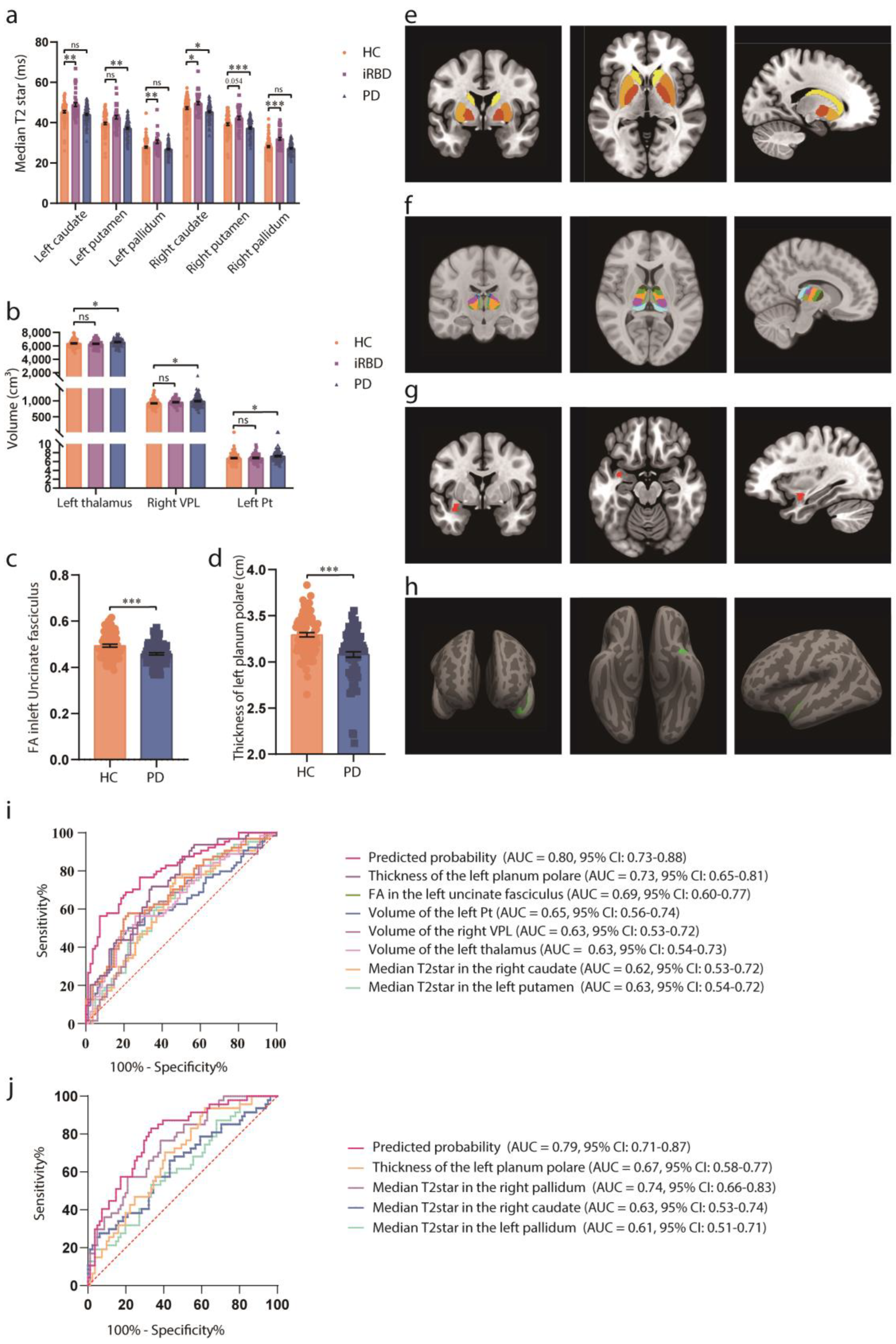

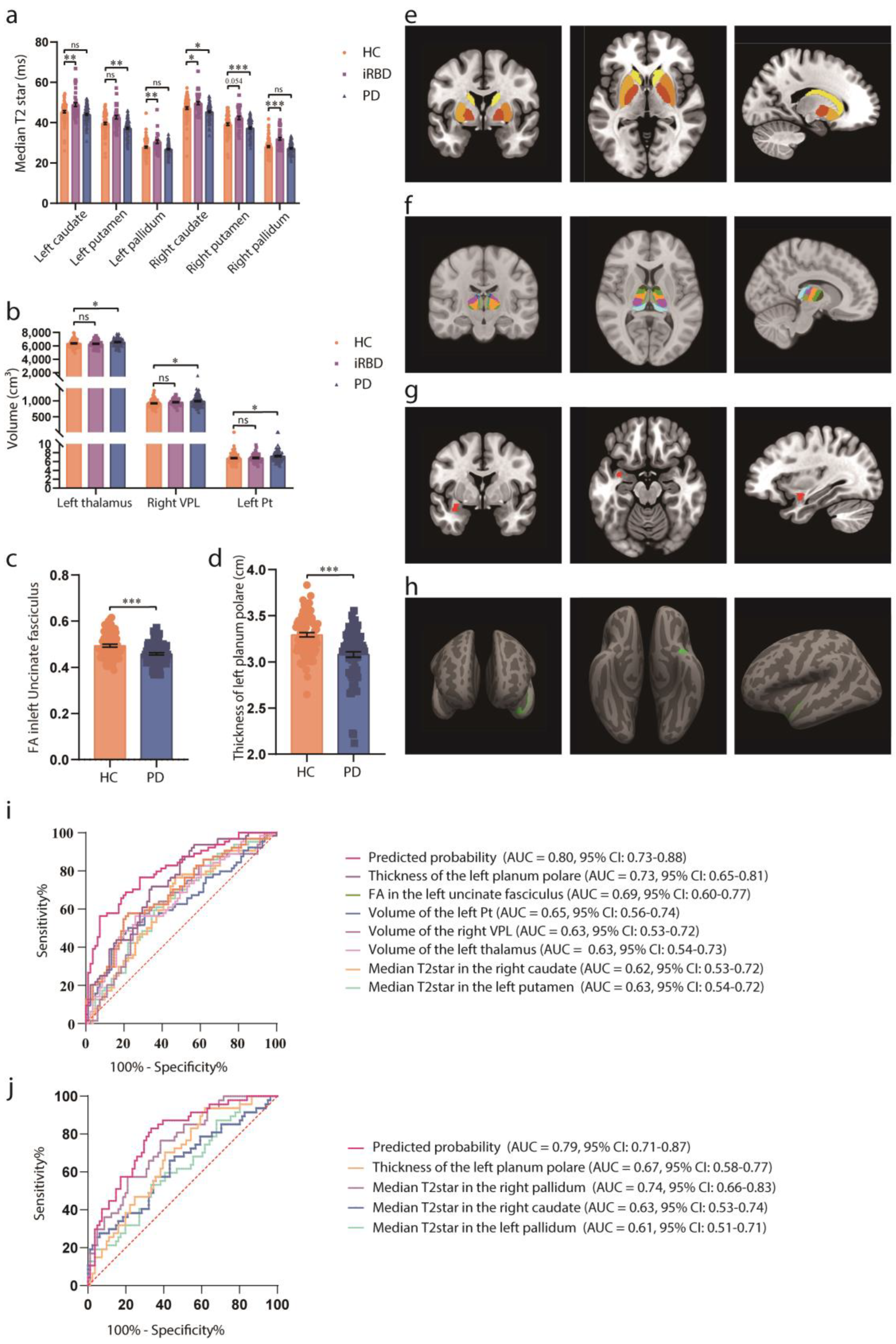

Figure 3.

Associations of brain IDPs and PD in the observational study. (a) Differences in median T2star in the caudate, putamen, and pallidum across HCs, patients with iRBD, and patients with PD. Patients with iRBD have higher median T2star values, while those with PD show lower values for both caudate sides. Similar results are observed in both sides of the pallidum and putamen. (b) Volumes of the thalamus, Pt, and VPL in HCs, participants with iRBD, and participants with PD. The thalamus volume is larger in both the iRBD and PD groups, with consistent results in the left Pt and right VPL. (c) FA in the left uncinate fasciculus in HCs, participants with iRBD, and participants with PD. FA is decreased in the left uncinate fasciculus in patients with PD. (d) Thickness of the left planum polare in HCs, participants with iRBD, and participants with PD. The thickness of the superior planum polare is reduced in patients with PD. (e-h) MRI pattern diagrams corresponding to a-d. Mean and SEM are used for precision and dispersion measures, setting SEM as error bars. We used a fixed effect model, with linear or nonlinear age and sex effect kept in the model. ANOVAs or Kruskal-Wallis tests are used depending on data distribution and homoscedasticity, with logarithmic transformation or reciprocal transformation performed if necessary. For multiple comparisons, Dunnett Contrast tests are performed after ANOVAs, and false discovery rate analyses are performed after Kruskal-Wallis tests. The discriminative power of the values is evaluated using ROC curve analysis. (i) ROC curve distinguishing HCs from early-stage PD participants. (j) ROC curve distinguishing HCs from iRBD participants. Significance codes: “ns” for no significance; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. Abbreviations: FA, fractional anisotropy; HCs, healthy controls; iRBD, idiopathic rapid-eye-movement sleep behavioral disorder; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PD, Parkinson’s disease; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; VPL, ventral posterolateral nucleus.

Figure 3.

Associations of brain IDPs and PD in the observational study. (a) Differences in median T2star in the caudate, putamen, and pallidum across HCs, patients with iRBD, and patients with PD. Patients with iRBD have higher median T2star values, while those with PD show lower values for both caudate sides. Similar results are observed in both sides of the pallidum and putamen. (b) Volumes of the thalamus, Pt, and VPL in HCs, participants with iRBD, and participants with PD. The thalamus volume is larger in both the iRBD and PD groups, with consistent results in the left Pt and right VPL. (c) FA in the left uncinate fasciculus in HCs, participants with iRBD, and participants with PD. FA is decreased in the left uncinate fasciculus in patients with PD. (d) Thickness of the left planum polare in HCs, participants with iRBD, and participants with PD. The thickness of the superior planum polare is reduced in patients with PD. (e-h) MRI pattern diagrams corresponding to a-d. Mean and SEM are used for precision and dispersion measures, setting SEM as error bars. We used a fixed effect model, with linear or nonlinear age and sex effect kept in the model. ANOVAs or Kruskal-Wallis tests are used depending on data distribution and homoscedasticity, with logarithmic transformation or reciprocal transformation performed if necessary. For multiple comparisons, Dunnett Contrast tests are performed after ANOVAs, and false discovery rate analyses are performed after Kruskal-Wallis tests. The discriminative power of the values is evaluated using ROC curve analysis. (i) ROC curve distinguishing HCs from early-stage PD participants. (j) ROC curve distinguishing HCs from iRBD participants. Significance codes: “ns” for no significance; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. Abbreviations: FA, fractional anisotropy; HCs, healthy controls; iRBD, idiopathic rapid-eye-movement sleep behavioral disorder; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PD, Parkinson’s disease; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; VPL, ventral posterolateral nucleus.

Table 1.

Clinicodemographic characteristics of the participants in the observational study.

Table 1.

Clinicodemographic characteristics of the participants in the observational study.

| |

HC

(n=81) |

iRBD

(n=47) |

PD

(n=85) |

p Value |

| Age (y) |

62.77 ± 8.10 |

67.1 ± 5.68 |

67.87 ± 6.97 |

<0.001 |

| Sex, n |

|

|

|

0.94 |

| Male |

40 (49%) |

23(49%) |

44 (52%) |

|

| Female |

41 (51%) |

24(51%) |

41 (48%) |

|

| Disease duration (m) |

- |

50.65 ± 15.74 |

97.49 ± 36.24 |

|

| H-Y stage |

- |

- |

1.97 ± 0.80 |

|

| UPDRS I score |

- |

- |

9.02 ± 5.46 |

|

| UPDRS II score |

- |

- |

11.84 ± 6.33 |

|

| UPDRS III score |

- |

- |

33.13 ± 15.19 |

|