Submitted:

28 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

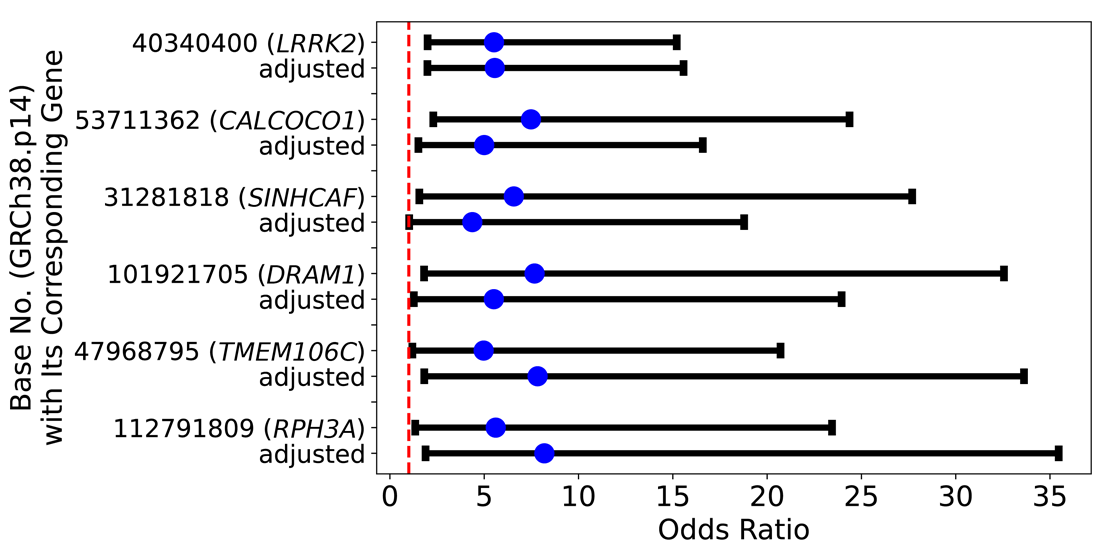

Background/Objectives: Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disease that develops with age and is related to a decline in motor function. Studies suggest that the causes may be based on genetic dysfunction including PARK gene mutations and environmental factors. Methods: To explore those factors, we used multivariable logistic regression to obtain odds ratios (ORs ) and adjusted ORs by using the All of Us Dataset which contains genomic, blood test, and other environmental data. Results: On Chromosome 12, there were 3,709 candidate single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are associated with PD. Of those SNPs, fifteen SNPs had high ORs which are similar to the OR of the PARK8 gene G2019S mutation. Of those 3,709 SNPs, a 2.00-fold change in OR was observed in five SNPs located at bases 53,711,362 (OR = 4.86, 95% CI [1.46, 16.18]), 31,281,818 (OR = 4.37, 95% CI [1.02, 18.82]), 101,921,705 (OR = 5.38, 95% CI [1.23, 23.51]), 47,968,795 (OR = 7.82, 95% CI [1.81, 33.83]), and 112,791,809 (OR = 8.05, 95% CI [1.85, 35.05]) by calcium, Vitamin D, and alcohol intake and were statistically significant. Conclusions: The results suggest that the progression of some PD caused by certain SNPs can be delayed or prevented by the environmental factors above. In February 2025, All of Us released the CT Dataset v.8 which has a 50% increase in the number of participants. Potentially, it may be possible to research more SNPs and environmental factors. In future studies, we would like to explore other environmental factors and SNPs on other chromosomes. It is believed that specific SNPs may tailor current treatments and qualify patients for clinical trials. Additionally, genetic knowledge may help increase accuracy in clinical trials.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s Disease

1.2. Definition of Monogenic and Idiopathic

1.3. Environmental Factors

1.3.1. Diets

1.3.2. Calcium

1.3.3. Vitamin D

1.3.4. Alcohol Intake

1.4. Genetic Factors

1.5. PARK8 /LRRK2 Gene and Environmental Factors

1.6. Research Question

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Definition of SNP in the All of Us Data

2.2. Preliminary Analysis

2.3. Power Analysis

2.3.1. Simple Logistic Regression for PD and SNPs

2.3.2. Multivariable Logistic Regression for PD, SNPs, and Environmental Factors

2.4. Data Processing

3. Results

3.1. PD and LRRK2 Gene SNPs

3.2. Other Bases That Have Similar ORs and p-Values of G2019S

3.3. PD and Environmental Factors

3.3.1. Factors and Statistical Power

3.4. Adjusted ORs of PD, SNPs, and Environmental Factors

3.4.1. Comparison of OR and AOR to Access the Environmental Factors’ Adjustment

3.4.2. AOR of SNPs Adjusted by Environmental Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| AOR | Adjusted odds ratio |

| AD GRCh38.p14 |

Alzheimer’s disease Genome Reference Consortium Human build 38 patch 14 |

References

- Jimenez-Ferrer, I.; Swanberg, M. Immunogenetics of Parkinson’s Disease. In Parkinson’s Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Aspects [Internet]; Codon Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, T.T.; Schapira, A.H.V. Genetic and Environmental Factors in the Cause of Parkinson’s Disease. Annals of Neurology: Official Journal of the American Neurological Association and the Child Neurology Society 2003, 53, S16–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, B.; Van Den Heuvel, L.; Van Prooije, T.; Van Ruissen, X.; Van De Warrenburg, B.; Nonnekes, J. Young Onset Parkinson’s Disease: A Modern and Tailored Approach. Journal of Parkinson’s disease 2020, 10, S29–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaxma, C.A.; Bloem, B.R.; Borm, G.F.; Oyen, W.J.G.; Leenders, K.L.; Eshuis, S.; Booij, J.; Dluzen, D.E.; Horstink, M.W.I.M. Gender Differences in Parkinson’s Disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2007, 78, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Parkinson Disease. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/parkinson-disease (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Willis, A.; Roberts, E.; Beck, J.; Fiske, B.; Ross, W.; Savica, R.; Van Den Eeden, S.; Tanner, C.; Marras, C.; C. Marras on behalf of the Parkinson’s Foundation P4 Group. Incidence of Parkinson Disease in North America. Incidence of Parkinson Disease in North America. npj Parkinson’s Disease 2022, 8, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grotewold, N.; Albin, R.L. Update: Descriptive Epidemiology of Parkinson Disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2024, 120, 106000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloem, B.R.; Okun, M.S.; Klein, C. Parkinson’s Disease. The Lancet 2021, 397, 2284–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSalvo, K.B. Public Health 3.0: A Call to Action for Public Health to Meet the Challenges of the 21st Century. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Martin, P.; Skorvanek, M.; Henriksen, T.; Lindvall, S.; Domingos, J.; Alobaidi, A.; Kandukuri, P.L.; Chaudhari, V.S.; Patel, A.B.; Parra, J.C.; et al. Impact of Advanced Parkinson’s Disease on Caregivers: An International Real-World Study. Journal of Neurology 2023, 270, 2162–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Balbuena, L.; Ungvari, G.S.; Zang, Y.-F.; Xiang, Y.-T. Quality of Life in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Comparative Studies. CNS neuroscience & therapeutics 2021, 27, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.-Q.; Zhu, F. Trends in Prevalence Cases and Disability-Adjusted Life-Years of Parkinson’s Disease: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Neuroepidemiology 2022, 56, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Health Estimates: Leading Causes of DALYs. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/global-health-estimates-leading-causes-of-dalys (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Pitz, V.; Makarious, M.B.; Bandres-Ciga, S.; Iwaki, H.; Singleton, A.B.; Nalls, M.; Heilbron, K.; Blauwendraat, C. Analysis of Rare Parkinson’s Disease Variants in Millions of People. NPJ Parkinson’s disease 2024, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, A.X.; Liao, Q.; Rohkin, G.; Bouça-Machado, R.; Guedes, L.C.; Ferreira, J.J.; Lee, S.M.-Y. Mitochondrial Methylation Two-Peak Profile Absent in Parkinson’s Disease Patient. bioRxiv 2017, 197731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesage, S.; Brice, A. Parkinson’s Disease: From Monogenic Forms to Genetic Susceptibility Factors. Human molecular genetics 2009, 18, R48–R59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorsey, E.R.; Bloem, B.R. Parkinson’s Disease Is Predominantly an Environmental Disease. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease 2024, 14, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraki, M.I.; Yannakoulia, M.; Stamelou, M.; Stefanis, L.; Xiromerisiou, G.; Kosmidis, M.H.; Dardiotis, E.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.M.; Sakka, P.; Anastasiou, C.A.; et al. Mediterranean Diet Adherence Is Related to Reduced Probability of Prodromal Parkinson’s Disease. Movement Disorders 2019, 34, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalay, R.N.; Gu, Y.; Mejia-Santana, H.; Cote, L.; Marder, K.S.; Scarmeas, N. The Association between Mediterranean Diet Adherence and Parkinson’s Disease. Movement Disorders 2012, 27, 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, V.E.; Rizzi, L.; Somaa, F. The Role of Nutrition on Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Nutritional Neuroscience 2023, 26, 605–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.-Q.; Yu, L.; Chen, W.; Tian, F.-W.; Zhai, Q.-X. Dietary Patterns Affect Parkinson’s Disease via the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 116, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, H.; Del Tredici, K.; Rüb, U.; De Vos, R.A.; Steur, E.N.J.; Braak, E. Staging of Brain Pathology Related to Sporadic Parkinson’s Disease. Neurobiology of aging 2003, 24, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotosho, A.O.; Tajudeen, Y.A.; Oladipo, H.J.; Yusuff, S.I.; AbdulKadir, M.; Muili, A.O.; Egbewande, O.M.; Yusuf, R.O.; Faniran, Z.O.; Afolabi, A.O.; et al. Parkinson’s Disease: Are Gut Microbes Involved? Brain and Behavior 2023, 13, e3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, S.S.; Sarfi, M.; Yousefi, T.; Ahangar, A.A.; Gholinia, H.; Ahangar, R.M.; Maniati, M.; Saadat, P. Comparison of the Calcium-Related Factors in Parkinson’s Disease Patients with Healthy Individuals. Caspian Journal of Internal Medicine 2020, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, L.; Lang, W.; Li, H.; Cui, P.; Zhang, N.; Jiang, W. Serum Calcium Levels and Parkinson’s Disease: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Frontiers in genetics 2020, 11, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleni, A.; Panagiotis, P. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Vitamin D and Calcium in Preventing Osteoporotic Fractures. Clinical rheumatology 2020, 39, 3571–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Tan, X.; Peng, X.; Bai, R.; Xiao, Q.; Zou, T.; Tan, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C. The Relationships of Vitamin D, Vitamin D Receptor Gene Polymorphisms, and Vitamin D Supplementation with Parkinson’s Disease. Translational neurodegeneration 2020, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmelzwaan, L.M.; van Schoor, N.M.; Lips, P.; Berendse, H.W.; Eekhoff, E.M.W. Systematic Review of the Relationship between Vitamin D and Parkinson’s Disease. Journal of Parkinson’s disease 2016, 6, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullard, M.E.; Duda, J.E. A Review of the Relationship between Vitamin D and Parkinson Disease Symptoms. Frontiers in neurology 2020, 11, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, E.; Fiore, A.; Yurasek, A.M.; Cook, R.L.; Boissoneault, J. Association of Therapeutic and Recreational Reasons for Alcohol Use with Alcohol Demand. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology 2023, 31, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institutes of Health Information about Alcohol. NIH Curriculum Supplement Series [Internet]; National Institutes of Health: Maryland, United States, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, H.; Tan, G.C.; Ibrahim, S.F.; Shaikh, M.F.; Mohamed, I.N.; Mohamed, R.M.P.; Hamid, A.A.; Ugusman, A.; Kumar, J. Alcohol Use Disorder, Neurodegeneration, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease: Interplay between Oxidative Stress, Neuroimmune Response and Excitotoxicity. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2020, 14, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genetic Alliance Genetics 101. Understanding Genetics: A New York, Mid-Atlantic Guide for Patients and Health Professionals; Genetic Alliance: Brisbane, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kouli, A.; Torsney, K.M.; Kuan, W.-L. Parkinson’s Disease: Etiology, Neuropathology, and Pathogenesis. In Parkinson’s Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Aspects [Internet]; Codon Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kasten, M.; Hartmann, C.; Hampf, J.; Schaake, S.; Westenberger, A.; Vollstedt, E.-J.; Balck, A.; Domingo, A.; Vulinovic, F.; Dulovic, M.; et al. Genotype-Phenotype Relations for the Parkinson’s Disease Genes Parkin, PINK1, DJ1: MDSGene Systematic Review. Movement Disorders 2018, 33, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.; Westenberger, A. Genetics of Parkinson’s Disease. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine 2012, 2, a008888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucking, C.B.; Durr, A.; Bonifati, V.; Vaughan, J.; De Michele, G.; Gasser, T.; Harhangi, B.S.; Meco, G.; Denefle, P.; Wood, N.W. Association between Early-Onset Parkinson’s Disease and Mutations in the Parkin Gene. New England Journal of Medicine 2000, 342, 1560–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanis, L. α-Synuclein in Parkinson’s Disease. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine 2012, 2, a009399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Burré, J. α-Synuclein in Synaptic Function and Dysfunction. Trends in neurosciences 2023, 46, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cookson, M.R. α-Synuclein and Neuronal Cell Death. Molecular neurodegeneration 2009, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzisch, M.; Yuan, B.; Chen, W.; Osaki, T.; Fu, D.; Garrett-Engele, C.; Svoboda, D.; Andrykovich, K.; Sur, M.; Jaenisch, R. The A53T Mutation in α-Synuclein Enhances pro-Inflammatory Activation in Human Microglia. bioRxiv 2023, 2023–08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilocchi, M.; Colugnat, I.; Lualdi, M.; Meduri, M.; Marini, F.; Corasolla Carregari, V.; Moutaoufik, M.T.; Phanse, S.; Pieroni, L.; Babu, M.; et al. Exploring the Impact of PARK2 Mutations on the Total and Mitochondrial Proteome of Human Skin Fibroblasts. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2020, 8, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershko, A.; Ciechanover, A. The Ubiquitin System. Annual review of biochemistry 1998, 67, 425–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MedlinePlus. UBE3A Gene. Available online: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/gene/ube3a/ (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Liang, Y.; Zhong, G.; Ren, M.; Sun, T.; Li, Y.; Ye, M.; Ma, C.; Guo, Y.; Liu, C. The Role of Ubiquitin–Proteasome System and Mitophagy in the Pathogenesis of Parkinson’s Disease. NeuroMolecular Medicine 2023, 25, 471–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polymeropoulos, M.H.; Higgins, J.J.; Golbe, L.I.; Johnson, W.G.; Ide, S.E.; Di Iorio, G.; Sanges, G.; Stenroos, E.S.; Pho, L.T.; Schaffer, A.A.; et al. Mapping of a Gene for Parkinson’s Disease to Chromosome 4q21-Q23. Science 1996, 274, 1197–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Wang, P.; Jankovic, J. The Genetics of Parkinson Disease. Ageing research reviews 2018, 42, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandres-Ciga, S.; Diez-Fairen, M.; Kim, J.J.; Singleton, A.B. Genetics of Parkinson’s Disease: An Introspection of Its Journey towards Precision Medicine. Neurobiology of disease 2020, 137, 104782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satake, W.; Nakabayashi, Y.; Mizuta, I.; Hirota, Y.; Ito, C.; Kubo, M.; Kawaguchi, T.; Tsunoda, T.; Watanabe, M.; Takeda, A.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Common Variants at Four Loci as Genetic Risk Factors for Parkinson’s Disease. Nature genetics 2009, 41, 1303–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucci, A.; Nalls, M.A.; Houlden, H.; Revesz, T.; Singleton, A.B.; Wood, N.W.; Hardy, J.; Paisán-Ruiz, C. Genetic Variability at the PARK16 Locus. European Journal of Human Genetics 2010, 18, 1356–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funayama, M.; Hasegawa, K.; Kowa, H.; Saito, M.; Tsuji, S.; Obata, F. A New Locus for Parkinson’s Disease (PARK8) Maps to Chromosome 12p11. 2–Q13. 1. Annals of Neurology: Official Journal of the American Neurological Association and the Child Neurology Society 2002, 51, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genome Reference Consortium. The Genome Reference Consortium. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/grc (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- National Library of Medicine. dbSNP. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/rs34637584 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Taymans, J.-M.; Fell, M.; Greenamyre, T.; Hirst, W.D.; Mamais, A.; Padmanabhan, S.; Peter, I.; Rideout, H.; Thaler, A. Perspective on the Current State of the LRRK2 Field. npj Parkinson’s Disease 2023, 9, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute Missense Mutation.

- Department of Health and Human Services. All of Us Research Hub. Available online: https://www.researchallofus.org/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- All of Us Research Program. Controlled CDR Directory (Archived C2022Q4R13 CDRv7). Available online: https://support.researchallofus.org/hc/en-us/articles/4616869437204-Controlled-CDR-Directory-Archived-C2022Q4R13-CDRv7 (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Python. Python Source Releases. Available online: https://www.python.org/downloads/source/ (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Hail Team. Install Hail on GNU/Linux. Available online: https://hail.is/docs/0.2/install/linux.html (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Pandas. Installation. Available online: https://pandas.pydata.org/docs/getting_started/install.html (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Jupyter. Installing Jupyter. Available online: https://jupyter.org/install (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Department of Health and Human Services. All of Us Controlled Tier Dataset v7 CDR Release Notes (C2022Q4R13). Available online: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1tr-WqlUsJicbF9QeCkvhvQmMiSiwEg4vSLiQ0A5zR_4/edit?tab=t.0#heading=h.k6xpincu6nx5.

- Buchner, A.; Erdfelder, E.; Faul, F.; Lang, A.-G. G*Power. Available online: https://www.psychologie.hhu.de/arbeitsgruppen/allgemeine-psychologie-und-arbeitspsychologie/gpower (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Peduzzi, P.; Concato, J.; Kemper, E.; Holford, T.R.; Feinstein, A.R. A Simulation Study of the Number of Events per Variable in Logistic Regression Analysis. Journal of clinical epidemiology 1996, 49, 1373–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns Hopkins University. Young-Onset Parkinson’s Disease. Available online: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/parkinsons-disease/youngonset-parkinsons-disease (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Kukkle, P.L.; Geetha, T.S.; Chaudhary, R.; Sathirapongsasuti, J.F.; Goyal, V.; Kandadai, R.M.; Kumar, H.; Borgohain, R.; Mukherjee, A.; Oliver, M.; et al. Genome-Wide Polygenic Score Predicts Large Number of High Risk Individuals in Monogenic Undiagnosed Young Onset Parkinson’s Disease Patients from India. Advanced Biology 2022, 6, 2101326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of California San Francisco. Calcium Blood Test. Available online: https://www.ucsfhealth.org/medical-tests/calcium-blood-test (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- National Institutes of Health. Calcium. Available online: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Calcium-HealthProfessional/ (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- University of Florida. 25-Hydroxy Vitamin D Test. Available online: https://ufhealth.org/conditions-and-treatments/25-hydroxy-vitamin-d-test (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D Status: Measurement, Interpretation, and Clinical Application. Annals of epidemiology 2009, 19, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Library of Medicine. NM_198578.4(LRRK2):C.6055G>A (p.Gly2019Ser) AND Young-Onset Parkinson Disease. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/261088770/.

- National Library of Medicine. CALCOCO1 Calcium Binding and Coiled-Coil Domain 1 [ Homo Sapiens (Human) ]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/57658 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Chen, W.; Ouyang, X.; Chen, L.; Li, L. Multiple Functions of CALCOCO Family Proteins in Selective Autophagy. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2022, 237, 3505–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, M.A.; Sykes, A.M.; Mellick, G.D. ER-Phagy in Neurodegeneration. Journal of Neuroscience Research 2023, 101, 1611–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-D.; Qi, L.; Wu, J.-C.; Qin, Z.-H. DRAM1 Regulates Autophagy Flux through Lysosomes. PLoS one 2013, 8, e63245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Library of Medicine. DRAM1 DNA Damage Regulated Autophagy Modulator 1 [ Homo Sapiens (Human) ]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/55332 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Morita, E. Membrane Closure in Stress Induced-Autophagosome Formation. Cell Stress 2018, 2, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Library of Medicine. SINHCAF SIN3-HDAC Complex Associated Factor [ Homo Sapiens (Human) ]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/58516 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Soudy, M.; Bars, S.L.; Glaab, E. Sex-Dependent Molecular Landscape of Alzheimer’s Disease Revealed by Large-Scale Single-Cell Transcriptomics. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2025, 21, e14476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H.-S.; Yuan, P.; Yu, J.-T. TMEM106B Aggregation in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Linking Genetics to Function. Molecular Neurodegeneration 2023, 18, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Library of Medicine. RPH3A Rabphilin 3A [ Homo Sapiens (Human) ]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/22895 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Wang, H.; Dou, S.; Wang, C.; Gao, W.; Cheng, B.; Yan, F. Identification and Experimental Validation of Parkinson’s Disease with Major Depressive Disorder Common Genes. Molecular Neurobiology 2023, 60, 6092–6108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Zhang, J. CSF α-Synuclein, Tau, and Amyloid β in Parkinson’s Disease. The Lancet Neurology 2011, 10, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablinger, C.; Geisler, S.M.; Stanika, R.I.; Klein, C.T.; Obermair, G.J. Neuronal A2δ Proteins and Brain Disorders. Pflügers Archiv-European Journal of Physiology 2020, 472, 845–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tröger, J.; Moutty, M.C.; Skroblin, P.; Klussmann, E. A-Kinase Anchoring Proteins as Potential Drug Targets. British journal of pharmacology 2012, 166, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perot, B.P.; Ménager, M.M. Tetraspanin 7 and Its Closest Paralog Tetraspanin 6: Membrane Organizers with Key Functions in Brain Development, Viral Infection, Innate Immunity, Diabetes and Cancer. Medical Microbiology and Immunology 2020, 209, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruchaga, C.; Bradley, J.; Western, D.; Wang, C.; Da Fonseca, E.L.; Neupane, A.; Kurup, J.; Ray, Ni.; Jean-Francois, M.; Gorijala, P.; et al. Novel Early-Onset Alzheimer-Associated Genes Influence Risk through Dysregulation of Glutamate, Immune Activation, and Intracell Signaling Pathways. Research square 2024, rs-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Library of Medicine. LALBA Lactalbumin Alpha [ Homo Sapiens (Human) ]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/3906 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- National Library of Medicine. RACGAP1 Rac GTPase Activating Protein 1 [ Homo Sapiens (Human) ]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/29127 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Bei, J.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, G.; Liu, X. The Protective Role of miR-132 Targeting HMGA2 through the PI3K/AKT Pathway in Mice with Alzheimer’s Disease. American Journal of Translational Research 2021, 13, 4632. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ayers, K.L.; Eggers, S.; Rollo, B.N.; Smith, K.R.; Davidson, N.M.; Siddall, N.A.; Zhao, L.; Bowles, J.; Weiss, K.; Zanni, G.; et al. Variants in SART3 Cause a Spliceosomopathy Characterised by Failure of Testis Development and Neuronal Defects. nature communications 2023, 14, 3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Library of Medicine. GATC Glutamyl-tRNA Amidotransferase Subunit C [ Homo Sapiens (Human) ]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/283459 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Shu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Pan, H.; Tang, B. A Comprehensive Analysis of Population Differences in LRRK2 Variant Distribution in Parkinson’s Disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2019, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Item | Category | Value | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| PD (n) | Positive | 369 | 1.08 |

| Negative | 33793 | 98.92 | |

| Age (n) | < 50 | 8310 | 24.33 |

| ≥ 50 | 25852 | 75.67 | |

| Sex (n) | Female | 24201 | 70.84 |

| Male | 9961 | 29.16 | |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | < 8.5 | 743 | 2.17 |

| ≥ 8.5 & < 9.0 | 4831 | 14.14 | |

| ≥ 9.0 & < 9.5 | 17183 | 50.3 | |

| ≥ 9.5 | 11405 | 33.39 | |

| Vitamin D (ng/mL) | < 20 | 5219 | 15.28 |

| ≥ 20 & < 30 | 9999 | 29.27 | |

| ≥ 30 & < 40 | 10394 | 30.43 | |

| ≥ 40 | 8550 | 25.03 | |

| Alcohol consumption (n) | Never | 6771 | 19.82 |

| Monthly or less | 11244 | 32.91 | |

| 2 to 4 per month | 7042 | 20.61 | |

| 2 to 3 per week | 4714 | 13.80 | |

| 4 or more per week | 4391 | 12.85 |

| Item | Category | PD positive (n = 369) |

PD negative (n = 33,793) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (n) | < 50 | 9 | 8301 | < .0001 |

| ≥ 50 | 360 | 25492 | ||

| Sex (n) | Female | 176 | 24025 | < .0001 |

| Male | 193 | 8301 | ||

| Calcium (mg/dL) | < 8.5 | 8 | 735 | < .0002 |

| ≥ 8.5 & < 9.0 | 84 | 4747 | ||

| ≥ 9.0 & < 9.5 | 180 | 17003 | ||

| ≥ 9.5 | 97 | 111308 | ||

| Vitamin D (ng/mL) | < 20 | 28 | 5191 | < .0002 |

| ≥ 20 & < 30 | 85 | 9914 | ||

| ≥ 30 & < 40 | 138 | 10256 | ||

| ≥ 40 | 118 | 8432 | ||

| Alcohol consumption (n) | Never | 103 | 6668 | .0382 |

| Monthly or less | 115 | 11129 | ||

| 2 to 4 per month | 53 | 6989 | ||

| 2 to 3 per week | 48 | 4666 | ||

| 4 or more per week | 50 | 4341 |

| Item | Category | AOR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (n) | < 50 | (Reference) | |

| ≥ 50 | 10.09 (5.18–19.64) | < .000 | |

| Sex (n) | Female | 0.41 (0.34–0.51) | < .000 |

| Male | (Reference) | ||

| Calcium (mg/dL) | < 8.5 | 0.63 (0.30–1.32) | 0.223 |

| ≥ 8.5 & < 9.0 | (Reference) | ||

| ≥ 9.0 & < 9.5 | 0.61 (0.47–0.79) | < .000 | |

| ≥ 9.5 | 0.49 (0.37–0.67) | < .000 | |

| Vitamin D (ng/mL) | < 20 | 0.70 (0.46–1.08) | 0.112 |

| ≥ 20 & < 30 | (Reference) | ||

| ≥ 30 & < 40 | 1.46 (1.11–1.92) | .007 | |

| ≥ 40 | 1.56 (1.17–2.07) | .002 | |

| Alcohol consumption (n) | Never | (Reference) | |

| Monthly or less | 0.89 (0.68–1.16) | .389 | |

| 2 to 4 per month | 0.59 (0.42–0.83) | .002 | |

| 2 to 3 per week | 0.73 (0.52–1.03) | .077 | |

| 4 or more per week | 0.66 (0.47–0.93) | .016 |

| Base No. (GRCh38.p14) | OR (95% CI) | Original p-value | Adjusted p-value | Gene Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1860203 | 5.58 (2.76–11.31) | < .000 | < .000 | CACNA2D4 |

| 4628152 | 5.43 (2.43–12.11) | < .000 | < .000 | AKAP3 |

| 11869533 | 5.94 (2.93–12.05) | < .000 | < .000 | ETV6 |

| 13537468 | 5.25 (2.97–9.27) | < .000 | < .000 | GRIN2B |

| 30983164 | 5.53 (2.60–11.76) | < .000 | < .000 | TSPAN11 |

| 38321345 | 5.77 (2.85–11.69) | < .000 | < .000 | ALG10B |

| 40340400 (G2019S) | 5.46 (2.90–10.27) | < .000 | < .000 | LRRK2 (PARK8) |

| 48569196 | 5.28 (2.61–10.70) | < .000 | < .000 | LALBA |

| 49990203 | 5.09 (2.26–11.48) | < .000 | .002 | RACGAP1 |

| 52107506 | 5.33 (2.36–12.02) | < .000 | .001 | SMIM41 |

| 65955867 | 5.06 (2.24–11.42) | < .000 | .002 | HMGA2 |

| 66254622 | 5.87 (2.89–11.89) | < .000 | < .000 | IRAK3 |

| 81260048 | 5.30 (2.35–11.96) | < .000 | .001 | ACSS3 |

| 108544453 | 5.01 (2.48–10.15) | < .000 | < .000 | SART3 |

| 120460300 | 5.69 (2.67–12.10) | < .000 | < .000 | GATC |

| Base No. (GRCh38.p14) | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR p-value | Gene Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 53711362 | 7.48 (2.30–24.37) | 5.00 (1.51–16.59) | .009 | CALCOCO1 |

| 31281818 | 6.57 (1.56–27.69) | 4.37 (1.02–18.78) | .047 | SINHCAF |

| 101921705 | 7.67 (1.81–32.56) | 5.51 (1.27–23.95) | .023 | DRAM1 |

| 47968795 | 4.97 (1.19–20.71) | 7.83 (1.82–33.62) | .006 | TMEM106C |

| 112791809 | 5.61 (1.34–23.44) | 8.19 (1.89–35.46) | .005 | RPH3A |

| Base No. (GRCh38.p14) | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR p-value | Gene Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1860203 | 4.77 (1.49–15.29) | 4.60 (1.41–15.03) | .012 | CACNA2D4 |

| 13537468 | 5.68 (1.41–22.82) | 4.52 (1.12–18.23) | .034 | GRIN2B |

| 30983146 | 5.12 (1.59–16.45) | 4.41 (1.35–14.45) | .014 | TSPAN11 |

| 40340400 (G2019S) | 5.52 (2.00–15.21) | 5.56 (1.99–15.57) | .001 | LRRK2 (PARK8) |

| 49990203 | 5.89 (1.82–18.99) | 4.29 (1.31–14.08) | .016 | RACGAP1 |

| 81260048 | 5.03 (1.57–16.45) | 4.23 (1.30–13.83) | .017 | ACSS3 |

| 120460300 | 5.22 (1.62–16.77) | 4.32 (1.33–14.05) | .015 | GATC |

| Item | Category | chr12:53711362 (n = 34,162) |

chr12: 31281818 (n = 34,158) |

chr12: 101921705 (n = 34,150) |

chr12: 47968795 (n = 34,144) |

chr12: 112791809 (n = 16,972) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR (95% CI) |

p-value | AOR (95% CI) |

p-value | AOR (95% CI) |

p-value | AOR (95% CI) |

p-value | AOR (95% CI) |

p-value | ||

| SNP | Reference nucleotide | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | |||||

| Polymorphic nucleotide | 4.86 (1.46–16.18) |

.010 | 4.37 (1.02–18.82) |

.048 | 5.38 (1.23–23.51) |

.025 | 7.82 (1.81–33.83) |

.006 | 8.05 (1.85 – 35.05) |

.005 | |

| Age (n) | < 50 | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | |||||

| ≥ 50 | 10.04 (5.16–19.55) |

< .000 | 10.08 (5.18–19.62) |

< .000 | 10.07 (5.17–19.60) |

< .000 | 10.10 (5.19–19.67) |

< .000 | 11.44 (4.22 – 31.01) |

< .000 | |

| Sex (n) | Female | 0.42 (0.34–0.52) |

< .000 | 0.41 (0.34–0.51) |

< .000 | 0.42 (0.34–0.51) |

< .000 | 0.41 (0.33–0.51) |

< .000 | 0.55 (0.40 – 0.74) |

< .000 |

| Male | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | ||||||

| Calcium (mg/dL) | < 8.5 | 0.56 (0.26–1.21) |

.014 | 0.64 (0.30–1.32) |

.227 | 0.64 (0.31–1.33) |

.227 | 0.64 (0.30–1.32) |

.226 | 0.66 (0.20 – 2.16) |

.489 |

| ≥ 8.5 & < 9.0 | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | ||||||

| ≥ 9.0 & < 9.5 | 0.61 (0.47–0.79) |

< .000 | 0.61 (0.47–0.79) |

< .000 | 0.61 (0.47–0.79) |

< .000 | 0.61 (0.47 – 0.79) |

< .000 | 0.68 (0.46 – 1.00) |

.050 | |

| ≥ 9.5 | 0.49 (0.37–0.67) |

< .000 | 0.50 (0.37–0.67) |

< .000 | 0.49 (0.37–0.67) |

< .000 | 0.49 (0.36–0.66) |

< .000 | 0.50 (0.32 – 0.78) |

.002 | |

| Vitamin D (ng/mL) | < 20 | 0.71 (0.46–1.09) |

.118 | 0.71 (0.46–1.09) |

.115 | 0.71 (0.46–1.09) |

.114 | 0.72 (0.46–1.10) |

.130 | 0.50 (0.24 – 1.03) |

.059 |

| ≥ 20 & < 30 | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | ||||||

| ≥ 30 & < 40 | 1.44 (1.10–1.90) |

.009 | 1.45 (1.11–1.91) |

.007 | 1.45 (1.11–1.91) |

.007 | 1.48 (1.13 – 1.95) |

.005 | 1.52 (1.02 – 2.26) |

.040 | |

| ≥ 40 | 1.55 (1.16–2.05) |

.003 | 1.55 (1.17–2.06) |

.002 | 1.56 (1.17–2.07) |

.002 | 1.59 (1.20 – 2.11) |

.001 | 1.76 (1.18 – 2.64) |

.006 | |

| Alcohol consumption (n) |

Never | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | |||||

| Monthly or less | 0.89 (0.68–1.17) |

.397 | 0.89 (0.67–1.16) |

.377 | 0.89 (0.68–1.17) |

.394 | 0.89 (0.68 – 1.16) |

.391 | 0.99 (0.67 – 1.46) |

.961 | |

| 2 to 4 per month | 0.59 (0.42–0.83) |

.002 | 0.59 (0.42–0.83) |

.002 | 0.59 (0.42–0.83) |

.002 | 0.58 (0.41 – 0.81) |

.002 | 0.66 (0.41 – 1.06) |

.085 | |

| 2 to 3 per week | 0.71 (0.50–1.01) |

.060 | 0.73 (0.52–1.04) |

.079 | 0.73 (0.51–1.03) |

.071 | 0.73 (0.51 – 1.03) |

.072 | 0.66 (0.39 – 1.13) |

.128 | |

| 4 or more per week | 0.65 (0.46–0.92) |

.015 | 0.66 (0.47–0.93) |

.016 | 0.66 (0.47–0.93) |

.016 | 0.66 (0.47 – 0.93) |

.017 | 0.70 (0.43 – 1.16) |

.165 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).