1. Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) leads to postural and motor impairments that significantly affect quality of life. Lateral hemisection of the spinal cord (LHS) including Brown-Séquard Syndrome results in ipsilateral postural deficits and proprioceptive loss, along with contralateral deficits in pain and temperature sensation [

1,

2,

3,

4]. These impairments are caused by the disruption of descending motor pathways and may be exacerbated by neuroplasticity of spinal neurocircuits [

5,

6]. Local spinal networks and descending pathways are reorganized, proprioceptive afferents promote synaptic rewiring, while corticospinal and rubrospinal tracts form new connections to bypass injury sites [

7,

8]. Maladaptive plastic changes lead to hyperreflexia, spasticity, and spasms [

5,

6].

The endogenous opioid system in the spinal cord is involved in regulation of sensory and motor processes [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. In the dorsal horn, it gates pain signals, whereas in the ventral spinal cord, opioid receptor activity may regulate motor circuits. After SCI, morphine acting through µ-opioid receptors impairs motor recovery [

14,

15], whereas the dynorphin - -opioid receptor signaling regulates scar formation [

16]. Block of opioid receptors can counteract changes in posture induced by unilateral traumatic brain injury. For example, naloxone, a general opioid antagonist, abolished hindlimb postural asymmetry (HL-PA) induced by brain injury [

17,

18,

19,

20].

Injury to one side of the brain often leads to motor and postural abnormalities on the opposite side of the body. These contralateral effects have long been attributed to the decussation of descending motor pathways, a cornerstone of neurological doctrine. However, growing evidence suggests that endocrine signaling may also contribute to such lateralized outcomes [

17,

19,

20,

21]. In rats with complete cervical or thoracic spinal cord transection—where descending neural input is eliminated—unilateral cortical injury induces HL-PA, typically manifesting as contralateral hindlimb flexion. This binary motor response is accompanied by lateralized changes in reflexes and gene expression in the lumbar spinal cord, implying involvement of humoral factors [

17,

20]. Supporting this notion, serum from brain-injured animals induces HL-PA in naïve recipients, while hypophysectomy abolishes the injury effect—implicating the hypothalamic–pituitary axis [

17].

Specific neurohormones have been linked to side-specific effects: β-endorphin and arginine vasopressin (AVP) are associated with right-side motor responses following left hemisphere injury, while dynorphin and Met-enkephalin mediate left-sided responses after right hemisphere lesions [

20]. These findings point to a lateralized neuroendocrine axis—termed the topographic neuroendocrine system—capable of encoding injury laterality and relaying signals via the circulation to peripheral effectors. The proposed topographic neuroendocrine system operates through a three-step process: (i) encoding of lateralized neural activity into neurohormonal signals by hypothalamic and pituitary structures; (ii) systemic dissemination through the bloodstream; and (iii) decoding into side-specific physiological effects at peripheral targets such as the spinal cord [

21].

Although previous work has focused on brain injury, we hypothesized that the LHS may similarly engage the topographic neuroendocrine system. Given its role as a neuroendocrine integrator, the hypothalamus could detect asymmetric spinal input—potentially ascending via neural pathways—and orchestrate the release of side-specific neurohormones. These hormones, once in circulation, may influence motor output via direct action or pituitary-mediated cascades.

In this study, we tested whether the postural consequences of LHS involve opioid mechanisms and whether humoral signaling contributes to HL-PA following right-sided SCI. Our results suggest that both the neural pathway, controlled by the opioid system, and the endocrine signaling are involved, while the topographic neuroendocrine system serves to translate lateralized spinal inputs into asymmetric hormonal signals that evoke motor responses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Male Wistar rats (Janvier Labs, France) weighing 150-200 g were used in the study. The animals received food and water ad libitum and were kept in a 12-h day-night cycle (light on from 10:00 p.m. to 10:00 a.m.) at a constant environmental temperature of 21°C (humidity: 65%) and randomly assigned to their respective experimental groups. Experiments were performed from 9:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. After the experiments were completed, the animals were given a lethal dose of pentobarbital or perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 4% paraformaldehyde.

Approval for animal experiments was obtained from the Malmö/Lund ethical committee on animal experiments (No.: M7-16).

Naloxone (5 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally.

2.2. Lateral Hemisection of the Spinal Cord

The rats were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane (Abbott, Norway) in a mixture with 65% nitrous oxide and 35% oxygen. Core temperature of the animals was controlled using a feedback-regulated heating system. Anaesthetized animals were mounted onto the stereotaxic frame and the skin of the back was incised along the midline at the level of the lower thoracic or cervical vertebrae. After the back muscles were retracted to the sides, a laminectomy was performed at the T8 and T9 vertebrae or the C6 and C7 vertebrae.

Under a surgical microscope, the spinal cord was hemisected on the right side using micro-scissors following local lidocaine application at the L1-L2 or C6-C7 levels [

22,

23]. To ensure precision, a 30-gauge needle was vertically inserted through the spinal cord midline with the beveled side oriented toward the right hemi-cord. The needle was advanced to penetrate the entire spinal cord and reach the ventral wall of the vertebral canal. One tip of the iridectomy/microsurgical scissors was inserted into the needle track at the midline, while the other tip was positioned along the lateral surface of the right hemi-cord. A complete hemisection of the right hemi-cord was then performed using the scissors. To confirm the completeness of the hemisection, the lateral edge of the needle was used as a knife to cut through the lesion gap. The procedure was further verified by visualizing the vertebral canal and ensuring a clear lesion gap under the surgical microscope. A piece of Spongostan (Medi-spon MDD) was placed between the rostral and caudal stumps of the spinal cord. The injury was verified during autopsy. After completion of all surgical procedures, the wounds were closed with 3-0 suture (AgnTho’s, Sweden) and the rat was kept under an infrared radiation lamp to maintain appropriate body temperature during monitoring of postural asymmetry.

2.3. Spinal Cord Transection

In the first set of experiments, 4 hours after the right hemisection at the L1-L2 level, a 3-4-mm spinal cord segment including the hemisection cut was dissected and removed [

17,

20]. In the second set of experiments, prior to the right side hemisection at the C6-C7 level (10 rats), a 3-4-mm spinal cord segment between the two vertebrae level was dissected at the L1-L2 and removed. The completeness of the transection was confirmed by (i) inspecting the cord during the operation to ensure that no spared fibers bridged the transection site and that the rostral and caudal stumps of the spinal cord were completely retracted; and (ii) examining the spinal cord in all animals after termination of the experiment.

2.4. Histological Analysis of SCI

To evaluate the extent of the hemisection, spinal cords from three rats with right lumbar LHS (the spinal cord was not completely transected) and three rats with right cervical LHS were processed and analyzed using Nissl staining. Three hours after lumbar LHS, HL-PA was measured and rats were transcardially perfused with 200 mL of saline, followed by 200 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4). Spinal cords were carefully extracted, post-fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, and then transferred to PBS containing 30% sucrose for cryoprotection. Samples were stored at 4°C for up to one week. A 10 mm segment of the spinal cord, including the hemisection site, was sectioned coronally into 20 μm slices.

Five sets of consecutive sections were collected, with sets 1, 3, and 5 stained using 1% toluidine blue (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. To determine the maximal lesion area, three adjacent sections corresponding to the submaximal lesion region were selected. The lesion areas were outlined on each section, and the total lesion area was calculated by stacking these outlines. The maximal lesion area was defined as the total area occupied by the lesion after stacking, expressed as a percentage of the total cross-sectional area.

2.5. Analysis of Hindlimb Postural Asymmetry (HL-PA)

The HL-PA value and the side of the flexed limb were assessed as described elsewhere [

17,

20]. Briefly, the measurements were performed under isoflurane anesthesia. The level of anesthesia was characterized by a barely perceptible corneal reflex and a lack of overall muscle tone. The anesthetized rat was placed in the prone position on the 1-mm grid paper. Silk threads were glued to the nails of the middle three toes of each hindlimb, and their other ends were tied to one of two hooks attached to the movable platform that was operated by a micromanipulator constructed in the laboratory [

17,

20,

24]. To reduce potential friction between the hindlimbs and the surface with changes in their position during stretching and after releasing them, the bench under the rat was covered with plastic sheet and the movable platform was raised up to form a 10° angle between the threads and the bench surface. The limbs were adjusted to lie symmetrically and stretching was performed over a distance of 1 cm at a rate of 2 cm/sec. The threads then were relaxed, the limbs were released and the resulting HL-PA was visually assessed or photographed. The procedure was repeated six times in succession, the postural asymmetry size was measured in millimeters as the length of the projection of the line connecting symmetric hindlimb distal points (digits 2-4) on the longitudinal axis of the rat, and the HL-PA values for a given rat were used in statistical analyses. The limb that projected over a shorter distance from the trunk was considered to be flexed. The HL-PA with negative and positive values were assigned as left and right hindlimb flexions, respectively.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by a statistician who was not involved in data acquisition to minimize bias. No intermediate assessment was performed to avoid any bias in data acquisition. The asymmetry data were obtained by unbiased hand-off method. Statistical analyses included repeated-measures ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc tests for multiple comparisons, two-tailed Student’s t-tests, and Fisher’s Exact two-tailed test. A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test confirmed that data did not significantly deviate from a normal distribution.

2.7. Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this work the author (G.B.) used ChatGPT4o in order to polish text. After using this service, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

3. Results

3.1. The Lumbar LHS-Induced HL-PA

HL-PA, a model for neurological deficits, provides a rapid, reliable measure of side-specific responses following unilateral neurotrauma [

17,

20,

21]. This binary model, producing either left or right-sided responses, replicates conditions such as hemiparesis and spastic dystonia secondary to traumatic brain injury and stroke. HL-PA was measured using a hands-off hindlimb stretching method, followed by visual or photographic documentation in anesthetized animals. Negative and positive values of HL-PA corresponded to left and right hindlimb flexion, respectively.

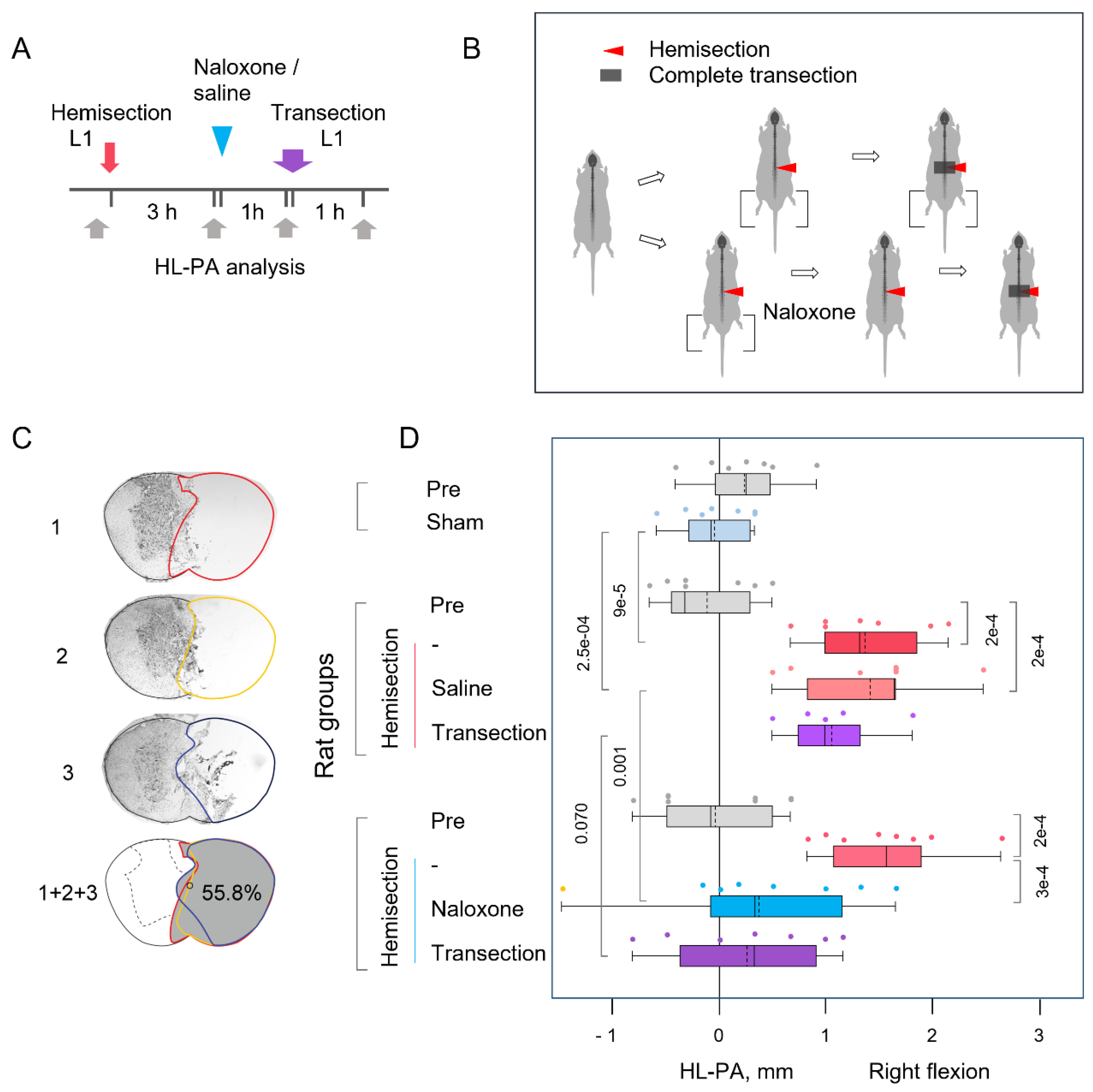

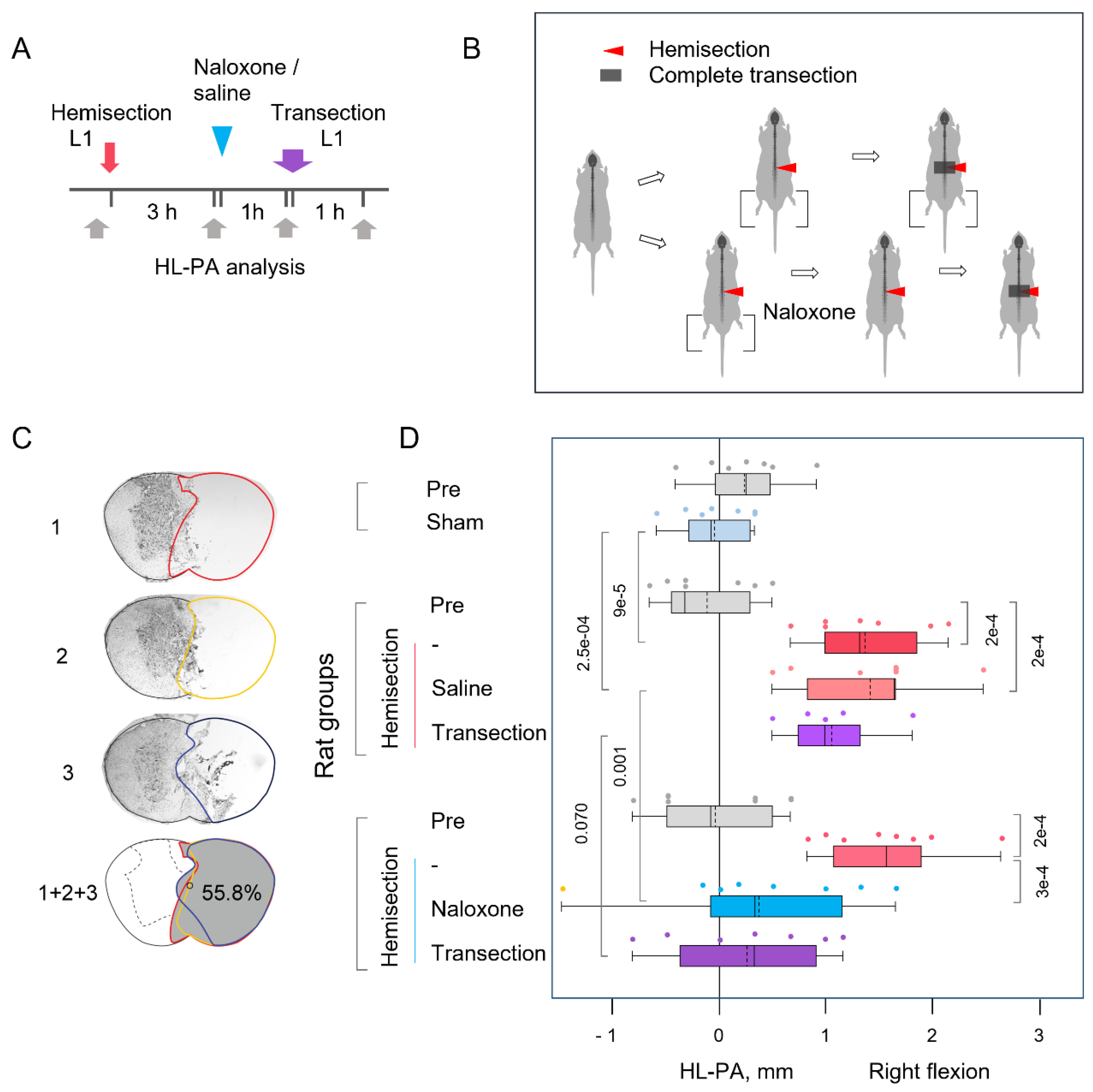

In the first set of experiments, a right-sided LHS was performed at the L1-L2 level (

Figure 1A,B). Four hours post-hemisection, the spinal cord was completely transected by removing a 3-4 mm segment at the hemisection level. HL-PA measurements were taken at baseline, three hours post-hemisection, one-hour post-naloxone or saline administration, and one hour after complete transection. Analysis of the lesion site in three rats showed that the right side of the spinal cord was nearly completely severed, with minor involvement of the left side (

Figure 1C). The maximal lesion areas measured 48.4%, 51.8%, and 55.8% of the total cross-sectional area, respectively.

Three hours after LHS, rats showed robust HL-PA, which was absent in sham-operated controls (

Figure 1D). Hindlimb was flexed on the ipsilesional side. Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed no significant main effect of treatment with naloxone (F(1,10)=1.71; P < 0.22), but it showed a significant main effect of time/repeated measures (F(3,30)=34.85, P < 1e-5) and a significant treatment time interaction (F(3,30)=6.87, P < 0.001), suggesting time-dependent differences in treatment response. Tukey's HSD pos thoc tests for this interaction showed significant differences between HL-PA values measured 3 hours post-hemisection and the baseline values (p<0.001 for both the “saline” and “naloxone” groups). Furthermore, the HL-PA values in rats with hemisected spinal cords were significantly higher than in sham-operated rats (Student’s t-test; P < 9e-5).

Following naloxone administration, HL-PA was significantly reduced by approximately 75% relative to pre-injection levels and the saline-treated group (Tukey’s post hoc test; P < 0.001), suggesting that LHS effects are mediated by opioid receptor activation. No significant changes in HL-PA were observed after complete spinal cord transection, suggesting that HL-PA may persist due to lumbar spinal cord plasticity induced by LHS. The proportion of rats with right-sided flexion after right-sided hemisection (15 with right flexion and none with left flexion) differed significantly from a random 50% left / 50% right distribution (Fisher’s Exact Test, two-tailed: P = 0.002).

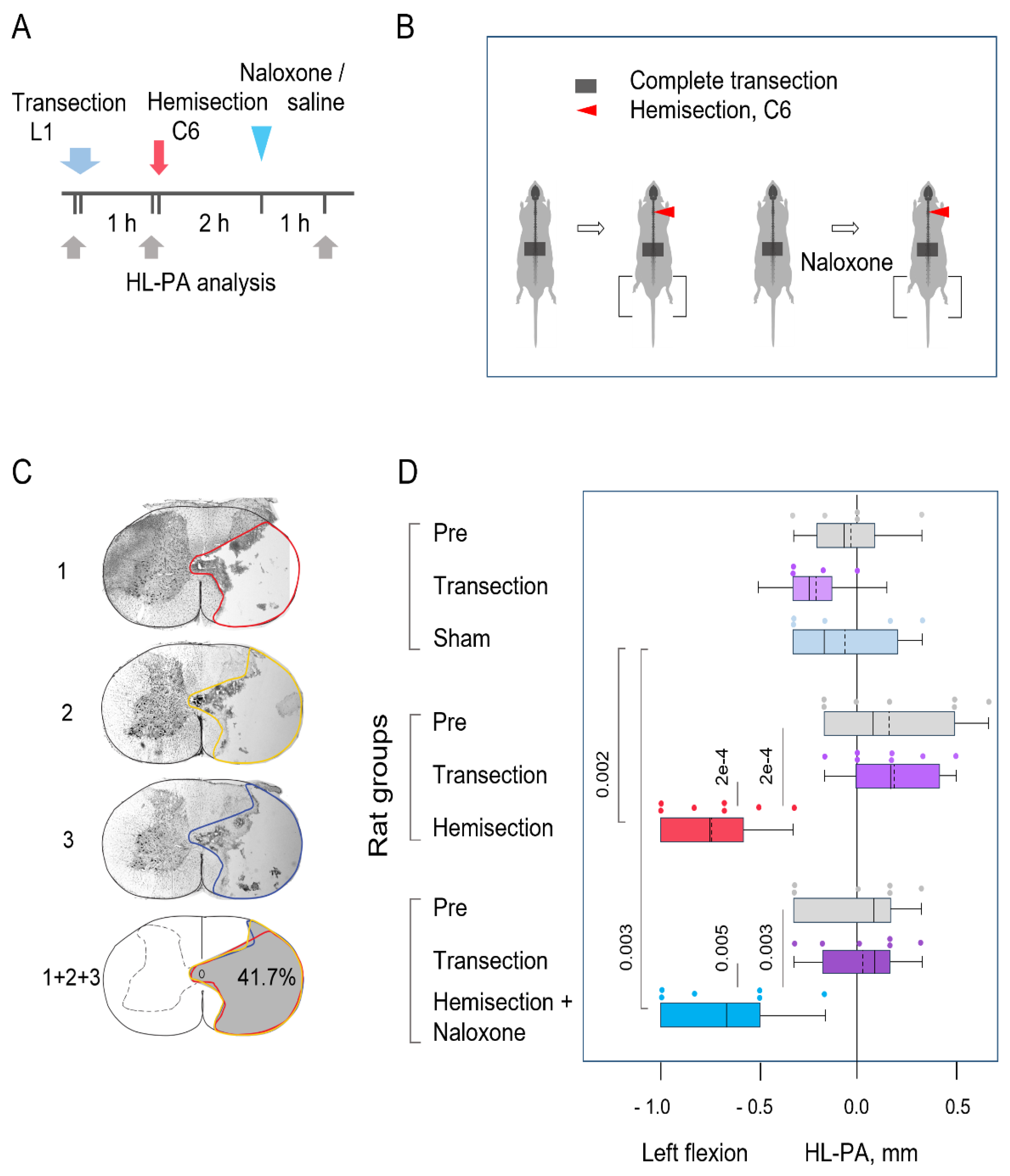

3.2. The Cervical LHS-Induced HL-PA in Rats with Complete Transection of Lumbar Spinal Cords

Unilateral brain injury can induce HL-PA through humoral pathway in animals with transected spinal cords [

17,

20,

21]. To test the involvement of a neuroendocrine mechanism in LHS effects, HL-PA was assessed in rats with right-sided cervical hemisection at C6-C7, performed 1 hour after a complete transection of the spinal cord at L1-L2 (

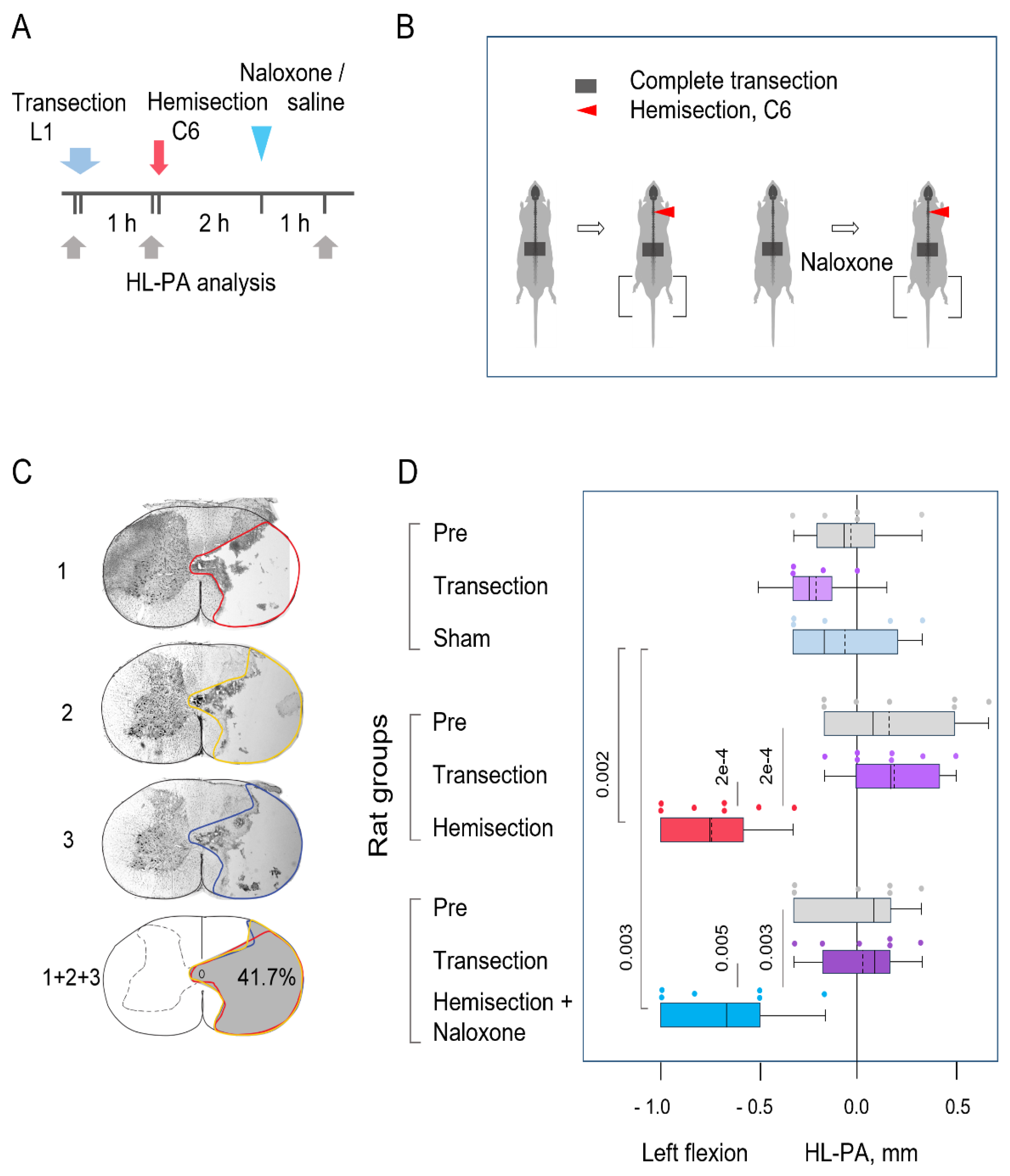

Figure 2). HL-PA was measured before and 3 hours after hemisection. Naloxone was administered 2 hours post-hemisection. The right side of the spinal cord was almost entirely severed, with minimal involvement of the left side (

Figure 2C). The maximal lesion areas for the three rats were 41.7%, 45.7%, and 52.3% of the total cross-sectional area, respectively.

The HL-PA size was higher in rats with right-sided cervical LHS than in i) the same rats 1 h after complete spinal transection and ii) rats with transected spinal cords after sham LHS (

Figure 2D). Cervical hemisection induced flexion of the left hindlimb. Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of hemisection (F(2,32)=21.79, P < 1e-5) and a significant interaction effect (F(4,32)=7.28, P < 3e-4), indicating differential responses over time among treatment groups. However, the main group effect was not significant (F(2,16)=0.64, P < 0.54). With respect to the “saline” and “naloxone” groups, post hoc tests identified significant HL-PA differences between the post-LHS time point and both the pre-hemisection and post-transection time points (see

Figure 2 for P values). In addition, post hoc comparisons confirmed a significant difference between the LHS groups and sham surgery group. No significant differences were observed between the “naloxone” and “saline” groups at any time point.

The proportion of rats with left-sided flexion after right cervical LHS (13 with left flexion and none with right flexion) differed significantly from both i) rats assessed one-hour post-transection (combined hemisection and sham surgery groups: 10 with left flexion vs. 7 with right flexion) and ii) a random 50% left / 50% right flexion distribution (Fisher’s Exact Test, two-tailed: P = 0.01 and P = 0.001, respectively). The difference in the proportions of left and right flexions between the lumbar and cervical LHS groups was highly significant (Fisher’s Exact Test, two-tailed: P = 3e-8).

4. Discussion

4.1. LHS-Induced HL-PA

The first finding of this study is that right-sided LHS induces HL-PA characterized by ipsilateral hindlimb flexion. This effect persisted after complete spinal transection caudal to, or at the level of, the hemisection—suggesting that the asymmetry arises from neuroplastic changes established in the lumbar spinal circuits prior to spinalization.

The emergence of ipsilateral flexion implies that asymmetric descending activity from the injury site induces plastic rearrangements in motor circuitry below the lesion. These findings align with earlier reports showing enhanced monosynaptic and polysynaptic reflex activity on the ipsilateral side following LHS, even after complete transection performed caudally [

25,

26].

As in previous HL-PA studies [

17,

18,

19,

20,

24], no nociceptive stimuli were applied, and tactile input was minimal upon the asymmetry analysis. Stretching of the hindlimbs was performed using thread attached to the toenails. Prior work showed that local anesthesia (lidocaine) applied to the toes did not influence HL-PA formation, excluding cutaneous nociceptive input as a contributing factor [

17,

24]. Furthermore, it has been well established that stretch and postural reflexes are abolished for days following complete spinal cord transection [

27,

28,

29], and are significantly suppressed under anesthesia [

30,

31]. These findings indicate that neither stretch reflexes nor nociceptive withdrawal responses are likely to contribute to HL-PA formation or maintenance in spinalized, anesthetized LHS rats. However, some proprioceptive circuits, particularly those involving group II muscle afferents, may remain active after acute spinalization and contribute to tone regulation [

32,

33,

34]. Taken together, the data support the idea that HL-PA is a multifactorial phenomenon, potentially arising from: i) persistent asymmetric activity of lumbar motoneurons independent of afferent drive, and/or ii) tonic activation of proprioceptive neurons—perhaps via group II afferents—that maintain baseline muscle tone.

Clinical observations show that many individuals with stroke or cerebral palsy exhibit persistent muscle activation in the absence of voluntary effort—termed spastic dystonia, defined as “stretch- and effort-unrelated sustained involuntary muscle activity following central motor lesions” [

35,

36]. This condition alters resting posture and contributes to hemiplegia [

37]. Spastic dystonia is considered a form of efferent motor hyperactivity and differs mechanistically from spasticity, which arises from enhanced reflex excitability [

38,

39]. Its pathogenesis may involve central, reflex-independent mechanisms. This hypothesis is supported by early work from Derek Denny-Brown, who demonstrated that lesions of the motor cortex in monkeys lead to persistent involuntary muscle activity, which was unaffected by elimination of afferent sensory input to the spinal cord [

40,

41]. These findings highlight the need for preclinical models to study spastic dystonia mechanisms [

35,

36,

37,

39,

42]. In this context, HL-PA induced by LHS in rats may serve as a model for studying this centrally driven, asymmetric motor phenomenon.

4.2. The Opioid HL-PA Mechanism

The neurotransmitter mechanisms of spinal neuroplasticity following unilateral neurotrauma remain unidentified, with the exception of a role of the opioid system [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Search for neurotransmitters mediating HL-PA formation demonstrated that opioid peptides and synthetic opioids [

43,

44,

45] along with Arg-vasopressin [

17] may be involved – they induce HL-PA in spinalized animals. These responses were side-specific: κ-opioid agonists such as dynorphin and bremazocine induced left hindlimb flexion, whereas δ-opioid agonist Leu-enkephalin and AVP elicited right hindlimb flexion. The fact that HL-PA can be elicited by intrathecal administration of opioid agonists in spinalized animals demonstrates that these effects are mediated though spinal circuits.

Pharmacological studies with opioid antagonists have shown that the opioid system is essential for HL-PA induced by unilateral brain injury, including ablation and controlled cortical impact of the sensorimotor cortex [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Consistent with these reports, our current findings suggest that opioid signaling contributes to HL-PA following the lumbar LHS. The non-selective opioid antagonist naloxone abolished postural asymmetry both before and after complete spinal transection, indicating that opioid mechanisms at the spinal level encode the LHS-induced response. We propose that the balance between mirror-symmetric spinal circuits regulating left and right hindlimb musculature is maintained by endogenous opioid tone. After LHS, this equilibrium may become disrupted by a side-specific activation of spinal opioid receptors, leading to asymmetric motor output.

The side-specific effects of opioids suggest that opioid receptors are lateralized within the spinal cord, and that these asymmetrically distributed receptors may differentially regulate the mirror-symmetric spinal circuits controlling left and right hindlimb muscles. Previous work identified asymmetric expression of opioid receptor genes in the cervical spinal cord [

19,

46], with all three receptor types (μ, δ, and κ) showing left-side dominance. Notably, the relative proportions of these receptors differed between the left and right spinal halves, and expression patterns were coordinated between dorsal and ventral regions, though differently on each side. These findings were then extended to the lumbar spinal cord, where similar lateralization patterns were observed. δ-Opioid receptor (Oprd1) expression was enriched on the left side, whereas the κ/δ receptor ratio (Oprk1/Oprd1) was higher on the right. Opioid peptides were also lateralized: Leu-enkephalin-Arg (a prodynorphin-derived marker) and the Leu-enkephalin-Arg to Met-enkephalin-Arg-Phe ratio were greater on the left, consistent with elevated prodynorphin-to-proenkephalin mRNA ratios in this region. In contrast, Met-enkephalin-Arg-Phe (a proenkephalin-derived marker) was enriched on the right side. These findings indicate that the lateralized organization of the spinal opioid system may provide a molecular substrate for side-specific modulation of neural activity in response to unilateral brain or spinal cord injury. Notably, Arg-vasopressin may act through activation of its V1B receptor in the pituitary gland that controls the release of opioid peptides into the bloodstream [

17].

Opioid peptides and receptors are expressed in interneurons in the dorsal and ventral spinal cord, where they regulate processing of sensory information, reflexes, and motor functions [

9,

48]. Opioid receptors are expressed by V1 inhibitory interneurons, which include premotor Ia interneurons mediating inhibition of antagonist muscles, and Renshaw cells mediating motor neuron recurrent inhibition but not motoneurons [

9]. Dynorphins are key components of a spinal inhibitory circuit and expressed by distinct subpopulations of inhibitory and excitatory neurons [

47]. Opioids modify ventral root reflexes by presynaptic inhibition of afferent signaling, postsynaptic repression of interneurons in the dorsal horn, and acting on interneurons regulating the activity of motoneurons in the ventral horn afferents [

11]. Spinal motor actions of opioids and opioid peptides are selectively directed onto pathways from flexor reflex afferents. Targeting opioid receptors in neurons that surround the central canal may inhibit the spinal commissural pathways and contralateral reflexes [

10,

13]. Spinal motor systems receive a convergent input from different supraspinal centers and different peripheral afferents projecting onto heterogeneous population of interneurons which many produce opioid peptides or are regulated through opioid receptors [

48,

49]. Thus, descending GABAergic neurons may inhibit dorsal horn enkephalinergic/GABAergic interneurons.

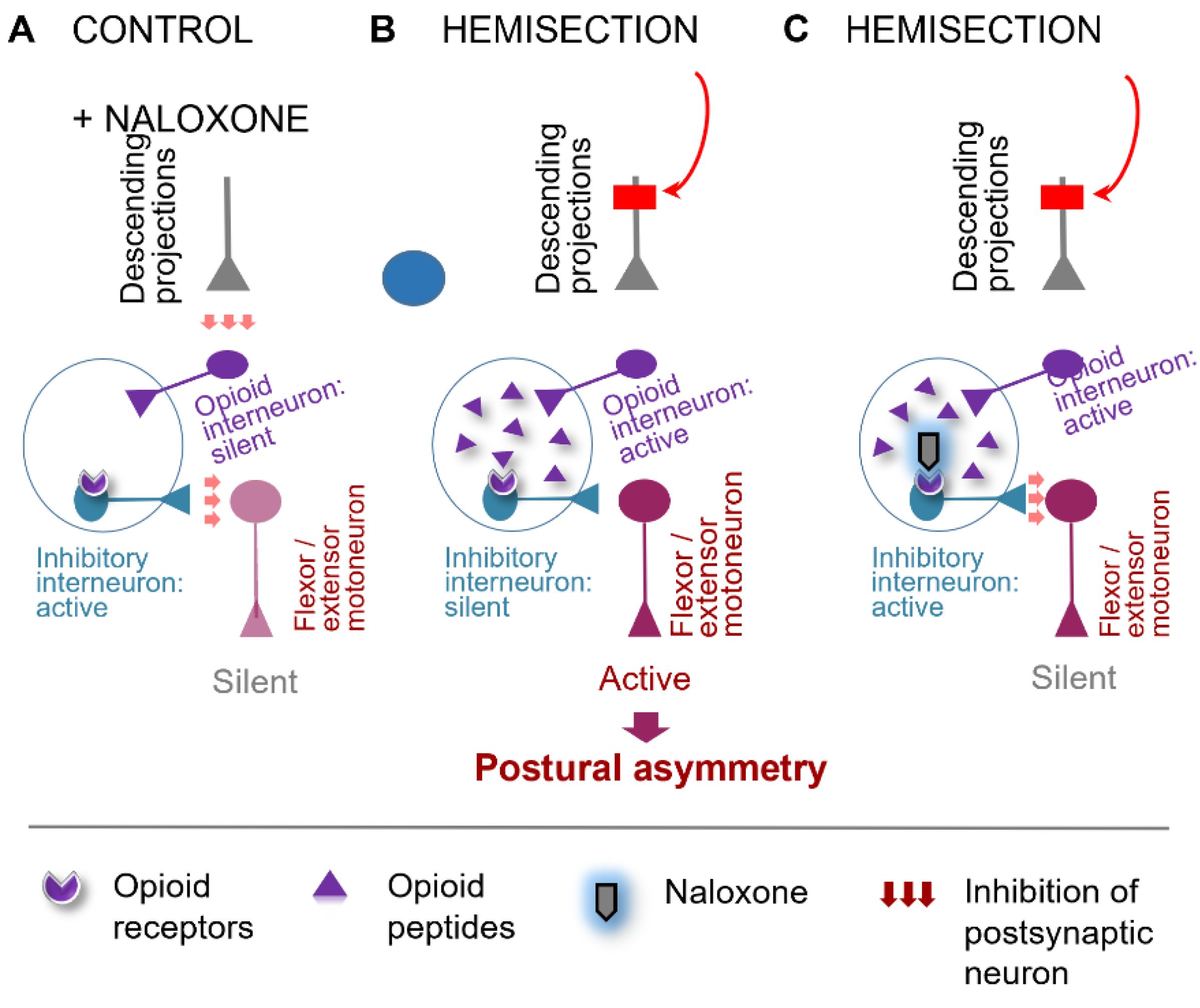

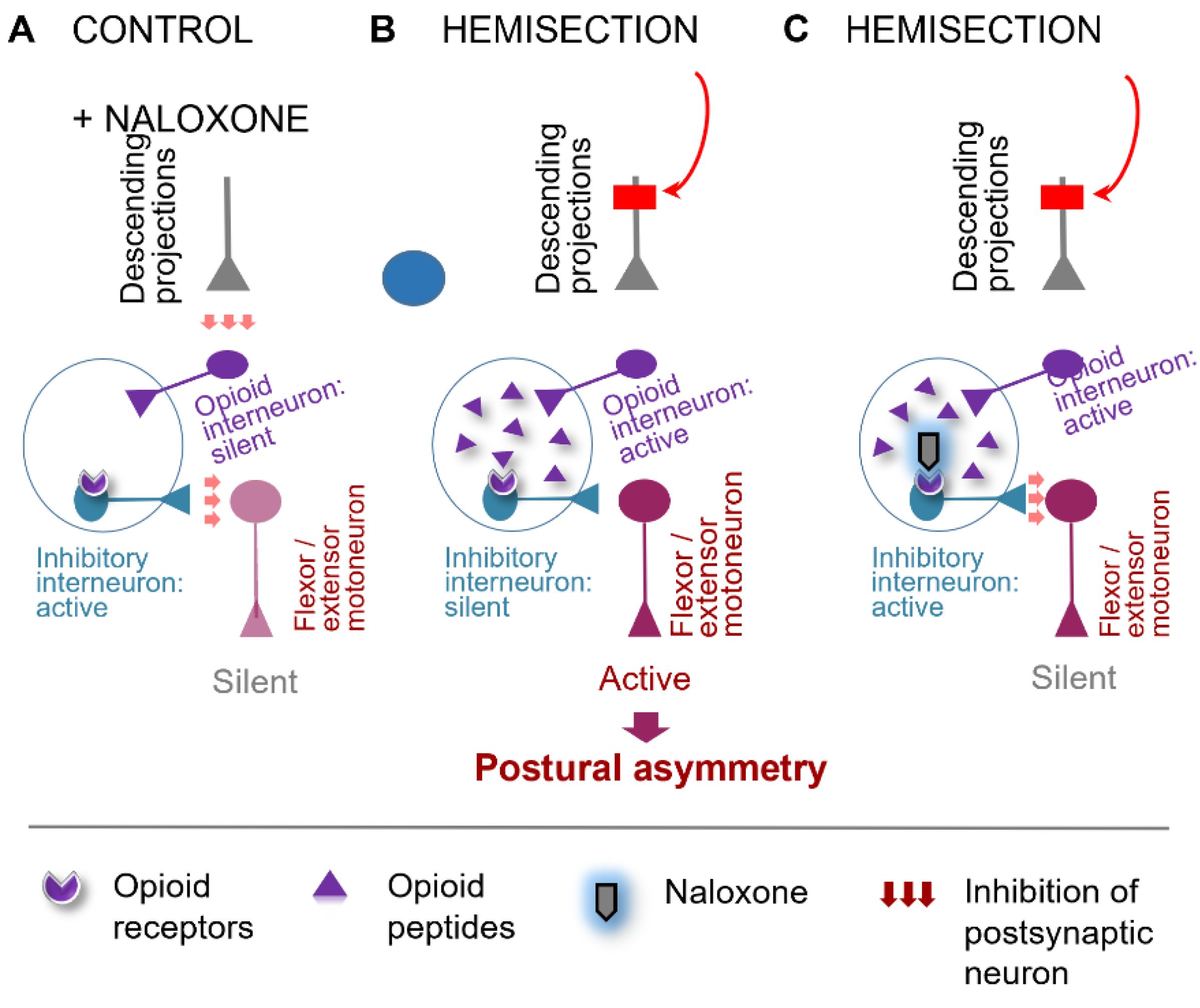

The model depicted in

Figure 3 illustrates the proposed mechanism by which the opioid system mediates the LHS-induced ipsilateral response. Under normal conditions, descending neural projections tonically inhibit opioid peptide-producing interneurons in the spinal cord. Following LHS, the loss of the descending control leads to the release of enkephalins or dynorphins on the injured side. Opioid peptides act on a neuronal subpopulation, which negatively regulates hindlimb motoneurons (

Figure 3B). Activation of opioid receptors on these interneurons suppresses their inhibitory activity, resulting in disinhibition of motoneurons. This causes pathological hindlimb responses, such as persistent muscle contraction (

Figure 3B). The administration of naloxone reverses these effects by restoring the activity of the opioid-sensitive interneurons. Consequently, motoneuron firing is suppressed, pathological responses on the ipsilesional side are reduced, and symmetry in posture and reflexes is restored (

Figure 3C). Plasticity of the opioid system may contribute to the maintenance of the pathological state after complete disconnection between the injury site and the lumbar spinal cord. This model and could be extended to other conditions where opioid mechanisms are involved.

Our opioid-related findings are consistent with clinical studies reporting that general opioid antagonists may reverse asymmetric neurological deficits following unilateral cerebral ischemia [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58]. In addition, opioid blockade has been shown to reduce spasticity in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis [

59].

These clinical observations, together with our experimental data, underscore the importance of identifying pathophysiological and molecular signatures of asymmetric motor deficits—such as hemiparesis and hemiplegia—that may be selectively mediated by different opioid receptor subtypes. Determining whether targeting these receptor-defined signatures with subtype-selective antagonists can promote functional recovery or compensation of postural deficits could have translational value for conditions such as spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, and stroke.

4.3. Humoral Signaling in HL-PA Formation

An intriguing finding was that cervical LHS, performed after complete lumbar spinal transection, produced HL-PA with flexion of the contralesional hindlimb. In spinalized animals, signals from the hemisection site to hindlimb motoneurons may be transmitted through a humoral pathway (

Figure 4). Specifically, the LHS-induced unilateral disruption of ascending sensory and proprioceptive signaling from spinal segments could provoke asymmetric responses in supraspinal structures including the hypothalamic-pituitary system. This may trigger the release of signaling molecules into the bloodstream, which then reach lumbar neurons or their projections onto hindlimb muscles, inducing postural asymmetry.

Previous studies unveiled the topographic neuroendocrine system, that mediates the contralateral effects of unilateral brain lesions on the lumbar spinal cords in rats with completely transected thoracis or cervical spinal cords [

17,

20,

21]. The humoral factors mediating the effects of left-sided injuries were identified as β-endorphin and Arg-vasopressin. In rats with intact brains, these peptides caused right hindlimb flexion. In contrast, dynorphin and Met-enkephalin may transmit the effects of right-sided brain injuries, and consistently cause left hindlimb flexion when injected intrathecally into the caudal part of the transected spinal cord of rats with intact brain [

18,

19,

20,

21].

Relevant to this study is that Met-enkephalin also induced HL-PA when it was administered intrathecally above the level of spinal cord transection. However, the hindlimb was flexed on right side [

60]. Notably, the side of the response was reversed when the effects of Met-enkephalin and LHS were transmitted through humoral pathways, compared to when they directly affected neurons in the lumbar spinal cord. In terms of its function, the reversal can counteract ipsilateral changes in reflexes and posture caused by hemisection-induced denervation of lumbar circuits. Naloxone reduced HL-PA only in the lumbar hemisection model and showed no significant effect after the cervical hemisection. Thus, the humoral transmission is not likely mediated by the opioid neurohormones.

One limitation of these findings is that they were obtained from anesthetized animals. Although the sympathetic system was ruled out as a signaling pathway from the injured brain to the lumbar spinal cord [

20], its potential involvement in the effects of LHS on HL-PA remains to be elucidated.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that spinal opioid receptor–mediated pathways, along with non-opioid humoral signaling, both contribute to asymmetric postural deficits following spinal cord hemisection. The extent to which these neural and neuroendocrine side-specific mechanisms interact or compensate for each other—and how they regulate lateralized processes across distributed CNS regions—remains an open question.

From a clinical standpoint, these findings highlight the potential of opioid receptor antagonists as therapeutic agents for alleviating side-specific neurological impairments after lateralized spinal injury. Moreover, identifying blood-borne factors that modulate or oppose side-specific opioid effects may inform novel strategies for restoring left–right motor balance in injury and disease.

Author Contributions

Hiroyuki Watanabe: investigation, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft. Igor Lavrov: formal analysis, data curation, conceptualization, visualization, validation. Mathias Hallberg: resources, methodology, writing – review & editing. Jens Schouenborg: resources, methodology, project administration. Mengliang Zhang: resources, funding acquisition; writing – original draft, writing – review & editing. Georgy Bakalkin: conceptualization, funding acquisition; supervision, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing.

Funding

Please add: The study was supported by the Swedish Research Council (Grants 2022-01182) and Uppsala University to G.B.; and by Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF20OC0065099) to M.Z..

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approval for animal experiments was obtained from the Malmö/Lund ethical committee on animal experiments (No.: M7-16).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Professor Nikolai V. Lukoyanov for statistical analysis and Dr. Karen Rich for histological processing of the spinal cord samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HL-PA |

Hindlimb postural asymmetry |

| LHS |

Lateral hemisection of the spinal cord |

| SCI |

Spinal cord injury () |

References

- Wirz M, Zörner B, Rupp R, Dietz V. Outcome after incomplete spinal cord injury: central cord versus Brown-Sequard syndrome. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:407-414. [CrossRef]

- Takeoka A, Arber S. Functional Local Proprioceptive Feedback Circuits Initiate and Maintain Locomotor Recovery after Spinal Cord Injury. Cell Rep. 2019;27(1):71-85.e3. [CrossRef]

- Zorner B, Bachmann LC, Filli L, at al. Chasing central nervous system plasticity: the brainstem’s contribution to locomotor recovery in rats with spinal cord injury. Brain. 2014;137:1716–1732.

- Aminoff, MJ. The life and legacy of Brown-Séquard. Brain. 2017;140(5):1525-1532. [CrossRef]

- Han Q, Ordaz JD, Liu NK, et al. Descending motor circuitry required for NT-3 mediated locomotor recovery after spinal cord injury in mice. Nat Commun 2019;10:5815. [CrossRef]

- Hutson TH, Di Giovanni S. The translational landscape in spinal cord injury: focus on neuroplasticity and regeneration. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15:732–745. [CrossRef]

- Asboth L, Friedli L, Beauparlant J, et al., Cortico-reticulo-spinal circuit reorganization enables functional recovery after severe spinal cord contusion. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21(4):576-588. [CrossRef]

- Han Q, Xie Y, Ordaz JD, et al. Restoring Cellular Energetics Promotes Axonal Regeneration and Functional Recovery after Spinal Cord Injury. Cell Metab. 2020;31(3):623-641.e8. [CrossRef]

- Wang D, Tawfik VL, Corder G, Low SA, Francois A, Basbaum AI, Scherrer G. Functional Divergence of Delta and Mu Opioid Receptor Organization in CNS Pain Circuits. Neuron 2018;98:90-108. [CrossRef]

- Clarke RW, Galloway FJ, Harris J, Taylor JS, Ford TW. Opioidergic inhibition of flexor and extensor reflexes in the rabbit. The Journal of physiology 1992;449:493-501. [CrossRef]

- Steffens H, Schomburg ED. Spinal motor actions of the mu-opioid receptor agonist DAMGO in the cat. Neuroscience research. 2011;70:44-54. [CrossRef]

- Faber ES, Chambers JP, Brugger F, Evans RH. Depression of A and C fibre-evoked segmental reflexes by morphine and clonidine in the in vitro spinal cord of the neonatal rat. British journal of pharmacology. 1997;120:1390-1396.

- . [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, E. Schomburg ED. A leu-enkephalin depresses transmission from muscle and skin non-nociceptors to first-order feline spinal neurones. The Journal of physiology 1998;510:513-525. [CrossRef]

- Terminel, M.N. , Bassil, C., Rau, J. et al. Morphine-induced changes in the function of microglia and macrophages after acute spinal cord injury. BMC Neurosci. 2022;23(1):58. [CrossRef]

- Rau J, Hemphill A, Araguz K, et al. Adverse Effects of Repeated, Intravenous Morphine on Recovery after Spinal Cord Injury in Young, Male Rats Are Blocked by a Kappa Opioid Receptor Antagonist. J Neurotrauma. 2022;39(23-24):1741-1755. [CrossRef]

- Yue WWS, Touhara KK, Toma K, Duan X, Julius D. Endogenous opioid signalling regulates spinal ependymal cell proliferation. Nature. 2024;634(8033):407-414. [CrossRef]

- Lukoyanov N, Watanabe H, Carvalho LS, et al. Left-right side-specific endocrine signaling complements neural pathways to mediate acute asymmetric effects of brain injury. eLife. 2021;10:e65247. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe H, Nosova O, Sarkisyan D, et al. Ipsilesional versus contralesional postural deficits induced by unilateral brain trauma: a side reversal by opioid mechanism. Brain Commun. 2020;2, fcaa208. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe H, Nosova O, Sarkisyan D, et al. Left-right side-specific neuropeptide mechanism mediates contralateral responses to a unilateral brain injury. eNeuro. 2021.

- Watanabe H, Kobikov Y, Nosova O, et al. The Left-Right Side-Specific Neuroendocrine Signaling from Injured Brain: An Organizational Principle. Function (Oxf). 2024;5(4):zqae013.

- . [CrossRef]

- Bakalkin, G. The left-right side-specific endocrine signaling in the effects of brain lesions: questioning of the neurological dogma. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022;79(11):545. [CrossRef]

- Lin XJ, Wen S, Deng LX, et al. Spinal cord lateral hemisection and asymmetric behavioral assessments in adult rats. J Vis Exp. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Webb AA, Muir GD. Compensatory locomotor adjustments of rats with cervical or thoracic spinal cord hemisections. J Neurotrauma. 2002;19:239-56. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Watanabe H, Sarkisyan D, et al. Hindlimb motor responses to unilateral brain injury: spinal cord encoding and left-right asymmetry. Brain Commun. 2020;2(1):fcaa055. [CrossRef]

- Hultborn H, Malmsten J. Changes in segmental reflexes following chronic spinal cord hemisection in the cat. I. Increased monosynaptic and polysynaptic ventral root discharges. Acta Physiol Scand. 1983;119(4):405-422. [CrossRef]

- Gossard JP, Delivet-Mongrain H, Martinez M, Kundu A, Escalona M, Rossignol S. Plastic Changes in Lumbar Locomotor Networks after a Partial Spinal Cord Injury in Cats. J Neurosci. 2015;35(25):9446-55. [CrossRef]

- Miller JF, Paul KD, Lee RH, Rymer WZ, Heckman CJ. Restoration of extensor excitability in the acute spinal cat by the 5-HT2 agonist DOI. J Neurophysiol. 1996 Feb;75(2):620-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musienko PE, Zelenin PV, Orlovsky GN, Deliagina TG. Facilitation of postural limb reflexes with epidural stimulation in spinal rabbits. J Neurophysiol. 2010 Feb;103(2):1080-92. Epub 2009 Dec 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Frigon A, Johnson MD, Heckman CJ. Altered activation patterns by triceps surae stretch reflex pathways in acute and chronic spinal cord injury. J Neurophysiol. 2011 Oct;106(4):1669-78. Epub 2011 Jul 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhou HH, Jin TT, Qin B, Turndorf H. Suppression of spinal cord motoneuron excitability correlates with surgical immobility during isoflurane anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1998 Apr;88(4):955-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchigami T, Kakinohana O, Hefferan MP, Lukacova N, Marsala S, Platoshyn O, Sugahara K, Yaksh TL, Marsala M. Potent suppression of stretch reflex activity after systemic or spinal delivery of tizanidine in rats with spinal ischemia-induced chronic spastic paraplegia. Neuroscience. 2011 Oct 27;194:160-9.022. Epub 2011 Aug 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jankowska, E. Interneuronal relay in spinal pathways from proprioceptors. Prog Neurobiol. 1992;38(4):335-78. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valero-Cabré A, Forés J, Navarro X. Reorganization of reflex responses mediated by different afferent sensory fibers after spinal cord transection. J Neurophysiol. 2004 Jun;91(6):2838-48. Epub 2004 Feb 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavrov I, Gerasimenko Y, Burdick J, Zhong H, Roy RR, Edgerton VR. Integrating multiple sensory systems to modulate neural networks controlling posture. J Neurophysiol. 2015 Dec;114(6):3306-14. Epub 2015 Oct 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gracies, JM. Pathophysiology of spastic paresis. I: Paresis and soft tissue changes. Muscle Nerve. 2005 May;31(5):535-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorentzen J, Pradines M, Gracies JM, Bo Nielsen J. On Denny-Brown's 'spastic dystonia' - What is it and what causes it? Clin Neurophysiol. 2018 Jan;129(1):89-94. Epub 2017 Nov 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinelli L, Currà A, Trompetto C, Capello E, Serrati C, Fattapposta F, Pelosin E, Phadke C, Aymard C, Puce L, Molteni F, Abbruzzese G, Bandini F. Spasticity and spastic dystonia: the two faces of velocity-dependent hypertonia. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2017 Dec;37:84-89. Epub 2017 Sep 27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheean G, McGuire JR. Spastic hypertonia and movement disorders: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and quantification. PM R. 2009 Sep;1(9):827-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baude M, Nielsen JB, Gracies JM. The neurophysiology of deforming spastic paresis: A revised taxonomy. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2019 Nov;62(6):426-430. Epub 2018 Nov 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denny-Brown, D. The cerebral control of movement. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press; 1966. p. 210-7.

- Denny-Brown, D. Preface: historical aspects of the relation of spasticity to movement. In: Feldman RG, Young RR, Koella WP, editors. Spasticity: disordered motor control. Chicago: Yearbook Medical 1980. p. 1-16.

- Pingel J, Bartels EM, Nielsen JB. New perspectives on the development of muscle contractures following central motor lesions. J Physiol. 2017 Feb 15;595(4):1027-1038. Epub 2016 Dec 7. PMCID: PMC5309377. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakalkin GIa, Iarygin KN, Trushina ED, Titov MI, Smirnov VN. Predpochtitel'noe razvitie fleksii levoĭ ili pravoĭ zadneĭ konechnosti pod deĭstviem sootvetstvenno metionin-énkefalina i leĭtsin-énkefalina [Preferential development of flexion of the left or right hindlimb as a result of treatment with methionine-enkephalin or leucine-enkephalin, respectively]. Dokl Akad Nauk SSSR. 1980;252(3):762-5. Russian. [PubMed]

- Chazov EI, Bakalkin GYa, Yarigin KN, Trushina ED, Titov MI, Smirnov VN. Enkephalins induce asymmetrical effects on posture in the rat. Experientia. 1981;37(8):887-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakalkin GYa, Kobylyansky AG. Opioids induce postural asymmetry in spinal rat: the side of the flexed limb depends upon the type of opioid agonist. Brain Res. 1989 Feb 20;480(1-2):277-89. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kononenko O, Galatenko V, Andersson M, Bazov I, Watanabe H, Zhou XW, Iatsyshyna A, Mityakina I, Yakovleva T, Sarkisyan D, Ponomarev I, Krishtal O, Marklund N, Tonevitsky A, Adkins DL, Bakalkin G. Intra- and interregional coregulation of opioid genes: broken symmetry in spinal circuits. FASEB J. 2017 May;31(5):1953-1963. Epub 2017 Jan 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Serafin EK, Paranjpe A, Brewer CL, Baccei ML. Single-nucleus characterization of adult mouse spinal dynorphin-lineage cells and identification of persistent transcriptional effects of neonatal hindpaw incision. Pain. 2021;162(1):203-218. [CrossRef]

- Schomburg ED. Spinal sensorimotor systems and their supraspinal control. Neurosci Res. 1990;7(4):265-340. [CrossRef]

- François A, Low SA, Sypek EI, et al. A Brainstem-Spinal Cord Inhibitory Circuit for Mechanical Pain Modulation by GABA and Enkephalins. Neuron. 2017;93(4):822-839.e6. [CrossRef]

- Baskin DS, Hosobuchi Y. Naloxone reversal of ischaemic neurological deficits in man. Lancet. 1981 Aug 8;2(8241):272-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosobuchi Y, Baskin DS, Woo SK. Reversal of induced ischemic neurologic deficit in gerbils by the opiate antagonist naloxone. Science. 1982 Jan 1;215(4528):69-71. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baskin DS, Kieck CF, Hosobuchi Y. Naloxone reversal and morphine exacerbation of neurologic deficits secondary to focal cerebral ischemia in baboons. Brain Res. 1984 Jan 9;290(2):289-96. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabaily J, Davis JN. Naloxone administration to patients with acute stroke. Stroke. 1984 Jan-Feb;15(1):36-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namba S, Nishigaki S, Fujiwara N, Wani T, Namba Y, Masaoka T. Opiate-antagonist reversal of neurological deficits--experimental and clinical studies. Jpn J Psychiatry Neurol. 1986 Mar;40(1):61-79. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skarphedinsson JO, Delle M, Hoffman P, Thorén P. The effects of naloxone on cerebral blood flow and cerebral function during relative cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1989 Aug;9(4):515-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hans P, Brichant JF, Longerstay E, Damas F, Remacle JM. Reversal of neurological deficit with naloxone: an additional report. Intensive Care Med. 1992;18(6):362-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baskin DS, Widmayer MA, Browning JL, Heizer ML, Schmidt WK. Evaluation of delayed treatment of focal cerebral ischemia with three selective kappa-opioid agonists in cats. Stroke. 1994 Oct;25(10):2047-53; discussion 2054. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Sun ZJ, Wu JL, Quan WQ, Xiao WD, Chew H, Jiang CM, Li D. Naloxone attenuates ischemic brain injury in rats through suppressing the NIK/IKKα/NF-κB and neuronal apoptotic pathways. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2019 Feb;40(2):170-179. Epub 2018 Jun 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gironi M, Martinelli-Boneschi F, Sacerdote P, Solaro C, Zaffaroni M, Cavarretta R, Moiola L, Bucello S, Radaelli M, Pilato V, Rodegher M, Cursi M, Franchi S, Martinelli V, Nemni R, Comi G, Martino G. A pilot trial of low-dose naltrexone in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2008 Sep;14(8):1076-83. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakalkin GYa, Kobylyansky AG, Nagornaya LV, Yarygin KN, Titov MI. Met-enkephalin-induced release into the blood of a factor causing postural asymmetry. Peptides. 1986;7(4):551-556. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Hindlimb postural asymmetry (HL-PA) induced by right-side hemisection of the lumbar spinal cord and the effects of naloxone. (A, B) Experimental Design: Hemisection was performed at the L1-L2 level, followed by administration of either saline (n=7) or naloxone (n=8) three hours later. One hour after injection, a complete spinal cord transection was performed by excising a 3 mm segment at the same level. Sham surgery was conducted as a control for hemisection in 7 rats. HL-PA was measured at four time points: before (Pre), three hours post-hemisection or sham surgery, one hour post-naloxone or saline administration, and one hour post-complete transection. (C) Representative images of the lesion site from a rat with a hemisection at the L1-L2 level. Images 1, 2, and 3 depict three adjacent sections representing the submaximal lesion area. The combined image (1+2+3) illustrates the maximal lesion area (shaded in gray) calculated by stacking the outlined regions from the three sections. In this rat, the lesion encompassed 55.8% of the spinal cord's cross-sectional area, which included the right half and small part of the left half of the spinal cord. (D) HL-PA size in millimeters with negative and positive values indicating flexion on the left and right sides, respectively. Boxplots show the distribution (minimum, first quartile, median, mean, third quartile, and maximum) with medians and means indicated by solid and dashed lines, respectively. Individual rat HL-PA values are shown by circles. Statistical Analysis: Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a main effect of repeated measurements (F(3,30)=34.85, P < 1e-5) and a significant interaction effect (F(3,30)=6.87, P < 0.001) but no significant group effect (naloxone) (F(1,10)=1.71, P < 0.22). Tukey’s HSD post hoc P-values are indicated on the plots. Two-tailed Student’s t-test compared hemisection and sham groups at the three-hour time point.

Figure 1.

Hindlimb postural asymmetry (HL-PA) induced by right-side hemisection of the lumbar spinal cord and the effects of naloxone. (A, B) Experimental Design: Hemisection was performed at the L1-L2 level, followed by administration of either saline (n=7) or naloxone (n=8) three hours later. One hour after injection, a complete spinal cord transection was performed by excising a 3 mm segment at the same level. Sham surgery was conducted as a control for hemisection in 7 rats. HL-PA was measured at four time points: before (Pre), three hours post-hemisection or sham surgery, one hour post-naloxone or saline administration, and one hour post-complete transection. (C) Representative images of the lesion site from a rat with a hemisection at the L1-L2 level. Images 1, 2, and 3 depict three adjacent sections representing the submaximal lesion area. The combined image (1+2+3) illustrates the maximal lesion area (shaded in gray) calculated by stacking the outlined regions from the three sections. In this rat, the lesion encompassed 55.8% of the spinal cord's cross-sectional area, which included the right half and small part of the left half of the spinal cord. (D) HL-PA size in millimeters with negative and positive values indicating flexion on the left and right sides, respectively. Boxplots show the distribution (minimum, first quartile, median, mean, third quartile, and maximum) with medians and means indicated by solid and dashed lines, respectively. Individual rat HL-PA values are shown by circles. Statistical Analysis: Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a main effect of repeated measurements (F(3,30)=34.85, P < 1e-5) and a significant interaction effect (F(3,30)=6.87, P < 0.001) but no significant group effect (naloxone) (F(1,10)=1.71, P < 0.22). Tukey’s HSD post hoc P-values are indicated on the plots. Two-tailed Student’s t-test compared hemisection and sham groups at the three-hour time point.

Figure 2.

Hindlimb postural asymmetry (HL-PA) induced by right-side hemisection of the cervical spinal cord in rats with prior lumbar spinal transection and the effects of naloxone. (A, B) Experimental Design: The lumbar spinal cord was transected completely at the L1-L2 level, followed by right-side hemisection at the C6-C7 level. Saline (n=7) or naloxone (n=6) was administered two hours post-hemisection. Five rats with transected spinal cords served as sham-operated controls. HL-PA was measured at multiple time points: before (Pre), one hour after complete transection, three hours post-hemisection or sham surgery, and one-hour post-naloxone or saline injection. (C) Representative images of the lesion site from a rat with a hemisection at the C6/7 level. Images 1, 2, and 3 depict three adjacent sections representing the submaximal lesion area. The combined image (1+2+3) illustrates the maximal lesion area (shaded in gray) calculated by stacking the outlined regions from the three sections. In this rat, the lesion encompassed 41.7% of the spinal cord's cross-sectional area, predominantly affecting the right half. (D) HL-PA size in millimeters with negative and positive values indicating flexion on the left and right sides, respectively. Boxplots show the distribution (minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, and maximum) with medians and means indicated by solid and dashed lines, respectively. Individual rat HL-PA values are shown by circles. Statistical Analysis: Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed significant effects of hemisection (F(2,32)=21.79, P < 1e-5) and interaction (F(4,32)=7.28, P < 3e-4), but no significant group effect (F(2,16)=0.64, P < 0.54). Tukey’s HSD post hoc P-values are shown. Boxplots display the minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, and maximum. Means are superimposed upon boxplots as dashed line (The dashed line shows the mean). The HL-PA values for individual rats are indicated by circles.

Figure 2.

Hindlimb postural asymmetry (HL-PA) induced by right-side hemisection of the cervical spinal cord in rats with prior lumbar spinal transection and the effects of naloxone. (A, B) Experimental Design: The lumbar spinal cord was transected completely at the L1-L2 level, followed by right-side hemisection at the C6-C7 level. Saline (n=7) or naloxone (n=6) was administered two hours post-hemisection. Five rats with transected spinal cords served as sham-operated controls. HL-PA was measured at multiple time points: before (Pre), one hour after complete transection, three hours post-hemisection or sham surgery, and one-hour post-naloxone or saline injection. (C) Representative images of the lesion site from a rat with a hemisection at the C6/7 level. Images 1, 2, and 3 depict three adjacent sections representing the submaximal lesion area. The combined image (1+2+3) illustrates the maximal lesion area (shaded in gray) calculated by stacking the outlined regions from the three sections. In this rat, the lesion encompassed 41.7% of the spinal cord's cross-sectional area, predominantly affecting the right half. (D) HL-PA size in millimeters with negative and positive values indicating flexion on the left and right sides, respectively. Boxplots show the distribution (minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, and maximum) with medians and means indicated by solid and dashed lines, respectively. Individual rat HL-PA values are shown by circles. Statistical Analysis: Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed significant effects of hemisection (F(2,32)=21.79, P < 1e-5) and interaction (F(4,32)=7.28, P < 3e-4), but no significant group effect (F(2,16)=0.64, P < 0.54). Tukey’s HSD post hoc P-values are shown. Boxplots display the minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, and maximum. Means are superimposed upon boxplots as dashed line (The dashed line shows the mean). The HL-PA values for individual rats are indicated by circles.

Figure 3.

A model for the opioid receptors mediated ipsilateral effects of the LHS on hindlimb posture. (A) Descending projections provide tonic inhibition to opioid neurons in the spinal cord that regulate the activity of inhibitory interneurons projecting onto motoneurons. As a result, motoneurons, which innervate hindlimb extensors and/or flexors, remain inactive. (B) LHS abolishes tonic inhibition of spinal opioid neurons on the injury side, leading to: i) activation and release of opioid peptides by opioid interneurons; ii) reduced activity of inhibitory interneurons projecting onto motoneurons; iii) activation of motoneurons; and iv) a resulting pathological response. (C) Naloxone blocks opioid receptors on the inhibitory interneurons, which then become active again and inhibit the motoneurons. This diminishes the pathological response on the ipsilesional side, reestablishing symmetry in posture and reflexes. The LHS-induced changes in opioid interneurons may account for the injury effects that persist even after complete spinal cord transection.

Figure 3.

A model for the opioid receptors mediated ipsilateral effects of the LHS on hindlimb posture. (A) Descending projections provide tonic inhibition to opioid neurons in the spinal cord that regulate the activity of inhibitory interneurons projecting onto motoneurons. As a result, motoneurons, which innervate hindlimb extensors and/or flexors, remain inactive. (B) LHS abolishes tonic inhibition of spinal opioid neurons on the injury side, leading to: i) activation and release of opioid peptides by opioid interneurons; ii) reduced activity of inhibitory interneurons projecting onto motoneurons; iii) activation of motoneurons; and iv) a resulting pathological response. (C) Naloxone blocks opioid receptors on the inhibitory interneurons, which then become active again and inhibit the motoneurons. This diminishes the pathological response on the ipsilesional side, reestablishing symmetry in posture and reflexes. The LHS-induced changes in opioid interneurons may account for the injury effects that persist even after complete spinal cord transection.

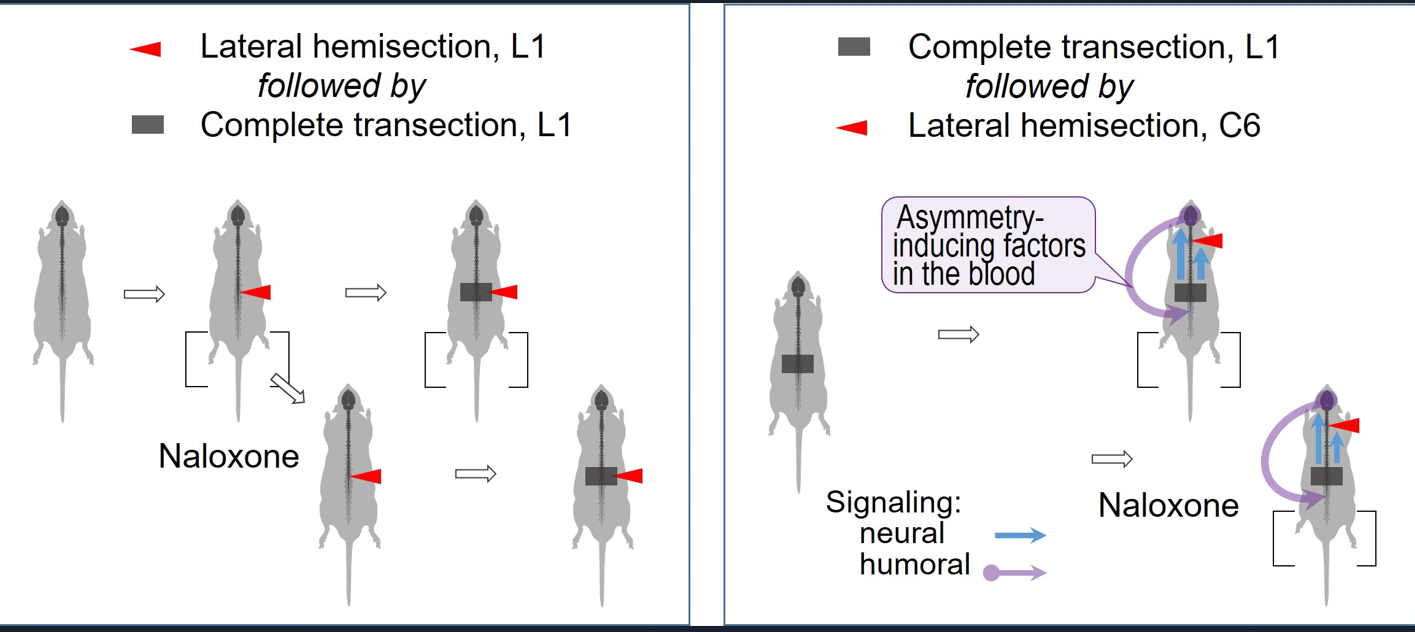

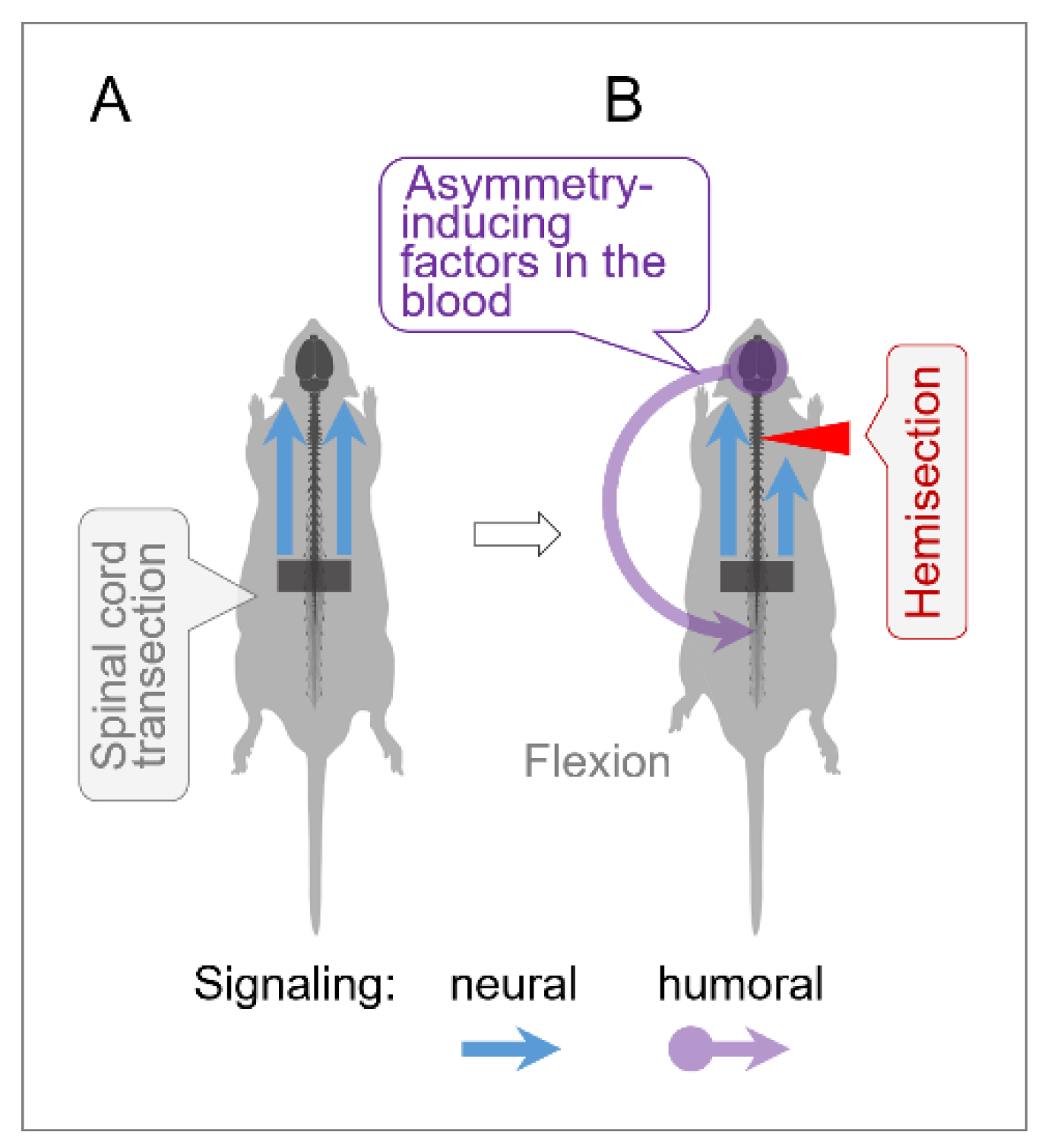

Figure 4.

Humoral side-specific signaling from the LHS site to the lumbar spinal cord. In rats with transected lumbar spinal cords, LHS unilaterally disrupts ascending sensory and proprioceptive signals from spinal segments rostral to the lumbar transection, triggering asymmetric responses in supraspinal structures. This may lead to the release of asymmetry-inducing molecules, likely from the hypothalamic-pituitary system [

17,

20,

21]. These molecules travel via the bloodstream to lumbar neurons or their projections onto hindlimb muscles, inducing contralesional hindlimb flexion.

Figure 4.

Humoral side-specific signaling from the LHS site to the lumbar spinal cord. In rats with transected lumbar spinal cords, LHS unilaterally disrupts ascending sensory and proprioceptive signals from spinal segments rostral to the lumbar transection, triggering asymmetric responses in supraspinal structures. This may lead to the release of asymmetry-inducing molecules, likely from the hypothalamic-pituitary system [

17,

20,

21]. These molecules travel via the bloodstream to lumbar neurons or their projections onto hindlimb muscles, inducing contralesional hindlimb flexion.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).