Submitted:

28 December 2024

Posted:

09 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Results

Study Characteristics

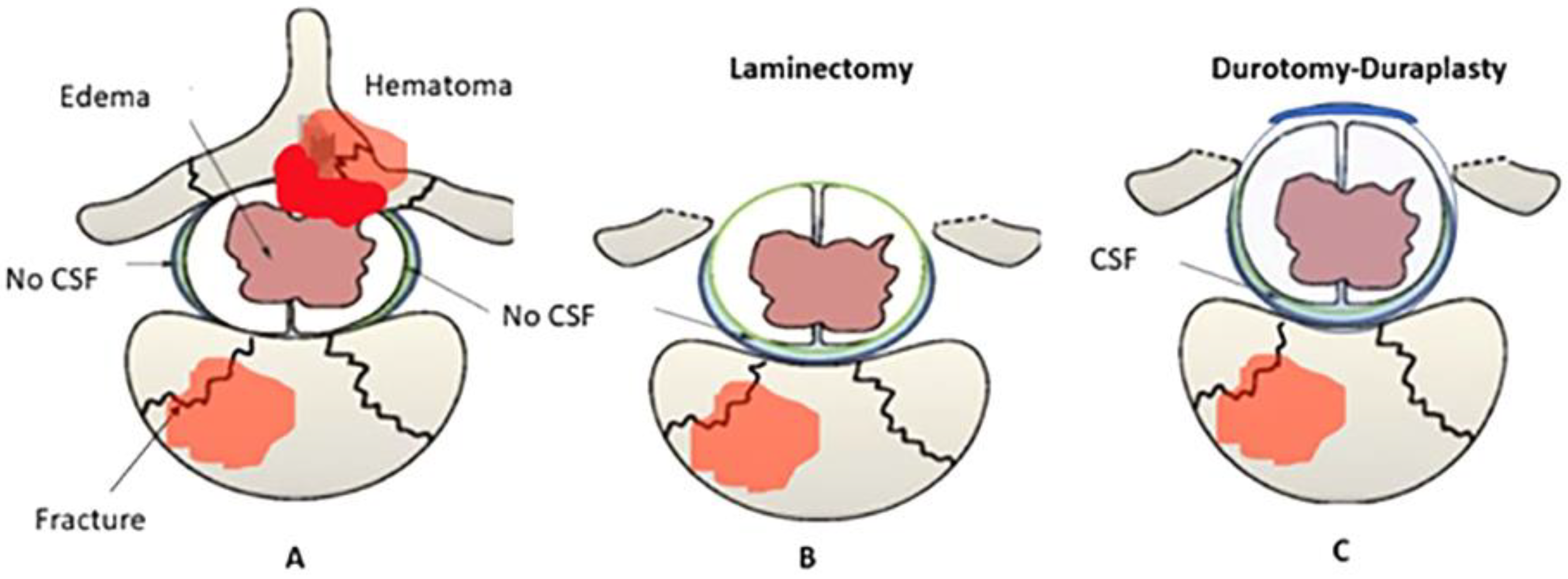

Pathophysiology of SCI

Discussion

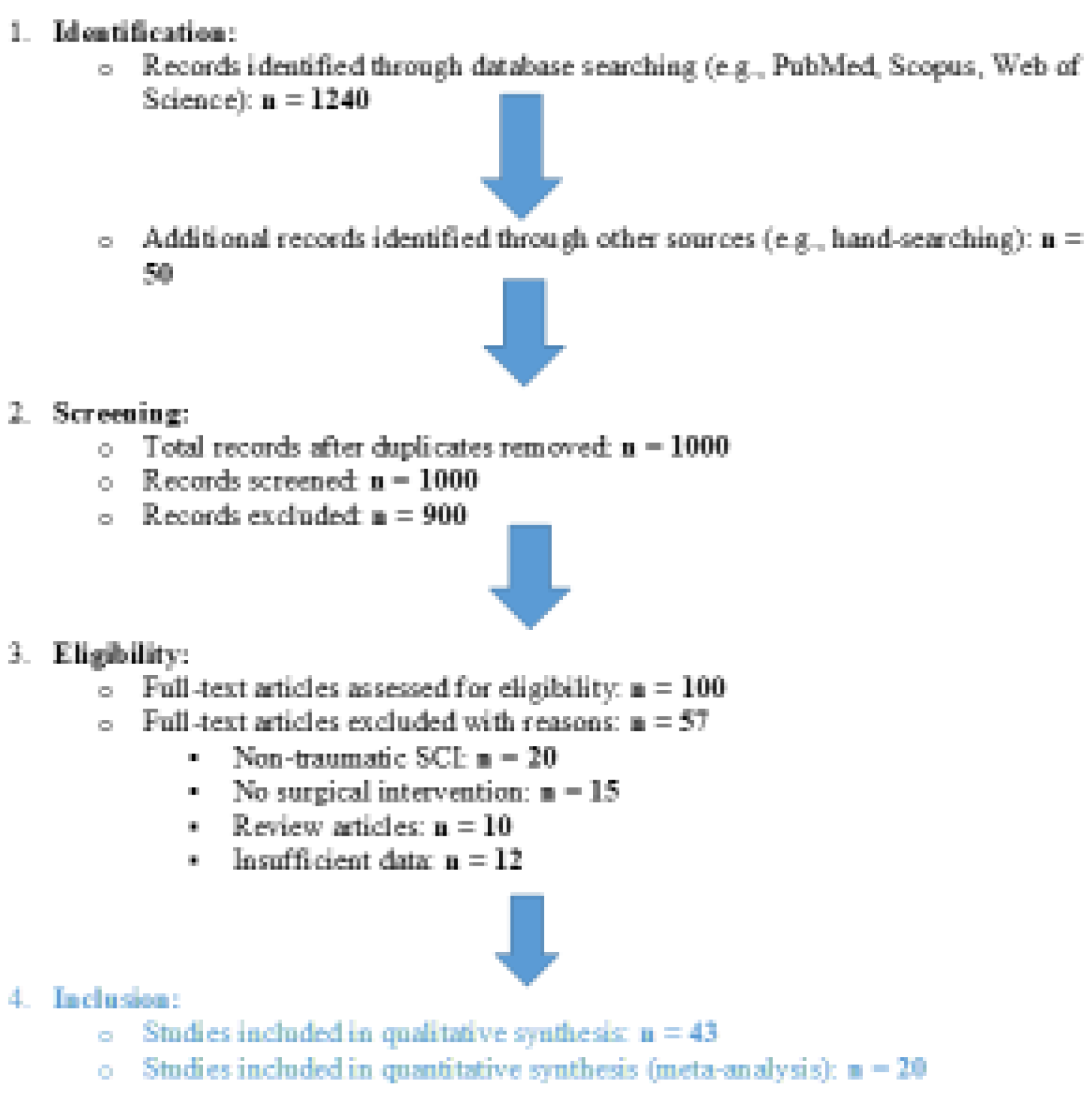

Methods

Search Strategy

Data Extraction

Quality Assessment

References

- Curt A, Van Hedel HJ, Klaus D, Dietz V: Recovery from a spinal cord injury: significance of compensation, neural plasticity, and repair. Journal of Neurotrauma 2008, 25:677-85. [CrossRef]

- Kornblith LZ, Kutcher ME, Callcut RA, Redick BJ, Hu CK, Cogbill TH, et al.: Mechanical ventilation weaning and extubation after spinal cord injury: a Western Trauma Association multicenter study. The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 2013, 75:1060-9. [CrossRef]

- Lenehan B, Street J, Kwon BK, Noonan V, Zhang H, Fisher CG, Dvorak MF: The epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury in British Columbia, Canada. Spine 2012, 37:321-9. [CrossRef]

- Thietje R, Pouw MH, Schulz AP, Kienast B, Hirschfeld S: Mortality in patients with traumatic spinal cord injury: descriptive analysis of 62 deceased subjects. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine 2011, 34:482-7. [CrossRef]

- Keefe KM, Sheikh IS, Smith GM: Targeting Neurotrophins to Specific Populations of Neurons: NGF, BDNF, and NT-3 and Their Relevance for Treatment of Spinal Cord Injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, 18. [CrossRef]

- Stoyanova I, Lutz D: Ghrelin-Mediated Regeneration and Plasticity After Nervous System Injury. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 9:595914. [CrossRef]

- Yue JK, Hemmerle DD, Winkler EA, Thomas LH, Fernandez XD, Kyritsis N, et al.: Clinical Implementation of Novel Spinal Cord Perfusion Pressure Protocol in Acute Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury at U.S. Level I Trauma Center: TRACK-SCI Study. World Neurosurgery 2020, 133:e391-e6. [CrossRef]

- Saadoun S, Papadopoulos MC: Targeted Perfusion Therapy in Spinal Cord Trauma. Neurotherapeutics 2020, 17:511-21. [CrossRef]

- Ahuja CS, Schroeder GD, Vaccaro AR, Fehlings MG: Spinal Cord Injury—What Are the Controversies? Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma 2017, 31 Suppl 4:S7-s13. [CrossRef]

- Anjum A, Yazid MD: Spinal Cord Injury: Pathophysiology, Multimolecular Interactions, and Recovery Mechanisms. Molecular Neurobiology 2020, 21:221-34. [CrossRef]

- Varsos GV, Werndle MC, Czosnyka ZH, Smielewski P, Kolias AG, Phang I, et al.: Intraspinal pressure and spinal cord perfusion pressure after spinal cord injury: an observational study. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine 2015, 23:763-71. [CrossRef]

- Kwon BK, Curt A, Belanger LM, et al.: Intrathecal pressure monitoring in acute spinal cord injury. Journal of Neurosurgery Spine 2009, 10:181-93.

- Phang I, Werndle MC, Saadoun S, Varsos G, Czosnyka M, Zoumprouli A, Papadopoulos MC: Expansion duroplasty improves intraspinal pressure, spinal cord perfusion pressure, and vascular pressure reactivity index in patients with traumatic spinal cord injury: injured spinal cord pressure evaluation study. Journal of Neurotrauma 2015, 32:865-74. [CrossRef]

- Werndle MC, Saadoun S, Phang I, Czosnyka M, Varsos GV, Czosnyka ZH, et al.: Monitoring of spinal cord perfusion pressure in acute spinal cord injury. Critical Care Medicine 2014, 42:646-55. [CrossRef]

- Punjani N, Deska-Gauthier D, Hachem LD, Abramian M, Fehlings MG: Neuroplasticity and regeneration after spinal cord injury. North American Spine Society Journal 2023, 15:100235. [CrossRef]

- Grassner L, Grillhösl A, Griessenauer CJ, Thomé C, Bühren V, Strowitzki M, Winkler PA: Spinal Meninges and Their Role in Spinal Cord Injury: A Neuroanatomical Review. Journal of Neurotrauma 2018, 35:403-10. [CrossRef]

- Zhu F, Yao S, Ren Z: Spinal cord expansion duroplasty and outcomes. Journal of Neurotrauma 2020, 35:235-40.

- Lau BY, Foldes AE, Alieva NO, Oliphint PA, Busch DJ, Morgan JR: Increased synapsin expression and neurite sprouting in lamprey brain after spinal cord injury. Experimental Neurology 2011, 228:283-93. [CrossRef]

- Ahuja CS, Nori S, Tetreault L, Wilson J, Kwon B, Harrop J, Choi D, Fehlings MG: Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury—Repair and Regeneration. Neurosurgery 2017, 80:S9-s22. [CrossRef]

- Sun X, Huang LY, Pan HX, et al.: Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and exercise restore motor function following spinal cord injury. Neural Regeneration Research 2023, 18:1067-75. [CrossRef]

- Zhong H, Xing C, Zhou M, Jia Z, Liu S: Alternating current stimulation promotes neurite elongation. Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica 2023, 55:1718-29. [CrossRef]

- Leonard AV, Thornton E, Vink R: The relative contribution of edema and hemorrhage to raised intrathecal pressure after traumatic spinal cord injury. Journal of Neurotrauma 2015, 32:397-402. [CrossRef]

- Leonard AV, Vink R: Reducing intrathecal pressure after traumatic spinal cord injury: a potential clinical target to promote tissue survival. Neural Regeneration Research 2015, 10:380-2. [CrossRef]

- Zhu F, Yao S, Ren Z, Telemacque D, Qu Y, Chen K, et al.: Early durotomy with duroplasty for severe adult spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality: a novel concept and method of surgical decompression. Spinal Cord 2019, 28:2275-82. [CrossRef]

- Chen T, Wu Y, Wang Y: Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Neural Stem Cells. Neurochemical Research 2017, 42:3073-83.

- Miao L, Qing SW, Tao L: Rehabilitation and MAPK/TrKA pathways. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 2023.

- Fehlings MG, Perrin RG: The timing of surgical intervention in the treatment of spinal cord injury: a systematic review of recent clinical evidence. Spine 2006, 31:S28-35. [CrossRef]

- Leonard AV, Thornton E, Vink R: Substance P as a mediator of neurogenic inflammation after spinal cord injury. Journal of Neurotrauma 2013, 30:1812-23. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Q, Zhu C, Li X, Shi Y, Zhang Z: CCR2 downregulation attenuates spinal cord injury by suppressing inflammatory monocytes. Molecular Therapy 2021, 75:e22191.

- Bobinger T, Burkardt P, Manaenko A: Programmed Cell Death after Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Current Neuropharmacology 2018, 16:1267-81. [CrossRef]

- Dimou L, Gallo V: NG2-glia and their functions in the central nervous system. Glia 2015, 63:1429-51.

- Kirdajova D, Valihrach L, Valny M: Transient astrocyte-like NG2 glia subpopulation emerges solely following permanent brain ischemia. Glia 2021, 69:2658-81. [CrossRef]

- Kirdajova D, Anderova M: NG2 cells and their neurogenic potential. Current Opinion in Pharmacology 2020, 50:53-60. [CrossRef]

- Singh PL, Agarwal N, Barrese JC, Heary RF: Current therapeutic strategies for inflammation following traumatic spinal cord injury. Neural Regeneration Research 2012, 7:1812-21. [CrossRef]

- Cozzens JW, Prall JA, Holly L: The 2012 Guidelines for the Management of Acute Cervical Spine and Spinal Cord Injury. Neurosurgery 2013, 72 Suppl 2:2-3. [CrossRef]

- Stoyanova II, Klymenko A, Willms J, et al.: Ghrelin Regulates Expression of Pax6 in Hypoxic Brain Progenitor Cells. Cells 2022, 11:24.

- Gotz M, Sirko S, Beckers J, Irmler M: Reactive astrocytes as neural stem or progenitor cells: in vivo lineage, in vitro potential, and genome-wide expression analysis. Glia 2015, 63:1452-68. [CrossRef]

- Hu J, Jin LQ, Selzer ME: Inhibition of central axon regeneration: perspective from chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans. Neural Regeneration Research 2022, 17:1955-6. [CrossRef]

- Galtrey CM, Fawcett JW: The role of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans in regeneration and plasticity in the central nervous system. Brain Research Reviews 2007, 54:1-18. [CrossRef]

- Leonard AV, Vink R: Reducing edema after traumatic spinal cord injury. Neuropharmacology 2016, 11:380-90.

- Saadoun S, Papadopoulos MC: Targeting spinal edema after injury. Neurotherapeutics 2019, 18:122-30.

- Garg K, Agrawal D, Hurlbert RJ: Expansive Duraplasty - Simple Technique with Promising Results in Complete Cervical Spinal Cord Injury: A Preliminary Study. Neurology India 2022, 70:319-24. [CrossRef]

- Lee JY, Chung H, Yoo YS: Inhibition of apoptotic cell death by ghrelin improves recovery after spinal cord injury. Endocrinology 2010, 151:3815-26. [CrossRef]

- le Feber J, Tzafi Pavlidou S, Erkamp N, et al.: Progression of Neuronal Damage in an In Vitro Model of Ischemia. PLOS One 2016, 11:e0147231. [CrossRef]

- Guo L, Lv J, Huang YF, et al.: Differentially expressed genes associated with spinal cord injury. Neural Regeneration Research 2019, 14:1262-70.

| Timeline | SCI Injury mechanism | Neuroplasticity |

| Acute (<48 hours)[1,2,3,5,10,15] |

Primary Injury: Direct trauma leads to hemorrhage, axonal shearing, and cellular necrosis. Demyelination and Necrosis: Demyelination and neuronal cell death rapidly follow mechanical damage. Blood-Spinal Cord Barrier Disruption (BSCB): A breach in the BSCB leads to increased permeability, allowing immune cell infiltration, especially neutrophils, which release metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), worsening tissue breakdown. Inflammation: Early immune response with neutrophil and macrophage infiltration. Pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) are upregulated, activating M1 microglia, releasing cytotoxic glutamate and nitric oxide, increasing cell death. |

Limited Neuroplasticity: Immediately following injury, neuroplasticity is significantly impaired due to the release of cytotoxic substances like glutamate. Synaptic circuits are abruptly disrupted, causing widespread loss of function. - Glutamate Toxicity: Excessive glutamate release causes excitotoxic damage, inhibiting early neural regeneration. - Neurotrophic Response: Limited neuroprotective responses, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) upregulation, are present but insufficient to counteract acute damage. - Axonal Injury: Axons near the injury site degenerate, reducing the potential for early plastic changes. |

| Subacute (2-14 days)[3,15,16,18,34,37,38] |

Continued Inflammation: The immune response escalates, with macrophages, T cells, and lymphocytes infiltrating the injury site. The presence of pro-inflammatory cytokines continues, prolonging tissue damage and cell death. Astrocytic and Glial Activation: Astrocytes proliferate and become reactive, losing aquaporin-4 (AQP4) activity. This worsens BSCB permeability and disrupts glutamate reuptake, contributing to neurotoxicity. Formation of CSPGs: Reactive astrocytes secrete chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs), inhibiting axonal regrowth. Ependymal Cell Activation: Self-renewing ependymal cells migrate to the injury site, forming astrocytes and contributing to scar formation. Glial Scar Formation Begins: Scar tissue, formed by activated astrocytes and fibrotic tissue, acts as a physical and chemical barrier to axonal regeneration. |

Early Plasticity : Some axonal sprouting occurs near the injury site, but neuroplasticity is primarily inhibited by CSPGs and the glial scar formation. -Ependymal Cell Contribution: Ependymal cells activate and proliferate, but their differentiation is mostly glial-biased (towards astrocytes), which limits their ability to support neuronal regeneration. -Axonal Sprouting and Circuit Reorganization: Axons near the lesion site begin sprouting, though inhibitory molecules like CSPGs largely block the growth. Maladaptive Changes: Initial signs of maladaptive neuroplasticity, such as aberrant sprouting or hyperexcitability, may appear, contributing to dysfunctional sensory and motor circuits. |

| Intermediate & Chronic Phase (>14 days/6 months)[3,10,15,16,19,20,25,34] |

Consolidation of Glial Scar: The glial scar, consisting of reactive astrocytes, macrophages, and CSPGs, fully develops, surrounding the fibrotic core formed by type A pericytes. This scar severely limits any potential for axonal regrowth. Chronic Inflammation: Microglia and macrophages continue to release pro-inflammatory cytokines, perpetuating neuroinflammation and preventing tissue repair. Wallerian Degeneration: Axonal degeneration (Wallerian degeneration) occurs distal to the injury, contributing to the ongoing loss of neural tissue. Demyelination: Ongoing demyelination of surviving neurons results in further functional loss, and oligodendrocyte apoptosis impairs remyelination efforts. Neuroimmune Modulation: Some immune cells (e.g., CD4+ T lymphocytes) may help shift the immune environment towards a more neuroprotective state, promoting limited repair mechanisms. |

Adaptive and Maladaptive Plasticity: Significant neuroplastic changes occur, with both beneficial (adaptive) and harmful (maladaptive) consequences. - Adaptive Plasticity: Propriospinal neurons, which span different spinal cord segments, sprout and form new synaptic connections to bridge the injury site. These new circuits can support partial recovery of motor functions. -Maladaptive Plasticity: Abnormal reorganization of spinal circuits may lead to spasticity, hyperreflexia, and sensory-evoked spasms, which worsen quality of life. Propriospinal Circuit Reorganization: Propriospinal neurons play a key role in forming compensatory circuits, enabling some recovery of locomotion, especially with rehabilitation interventions. Potential for Neurogenesis: Though limited, some endogenous neural stem/progenitor cells may contribute to neurogenesis, especially in the presence of factors like IL-4, which promote axonal growth and neurotrophic support. |

| Study | Study Design | Population | Intervention | Outcomes | |

| 1 | Garg et al., 2022 | Clinical - Retrospective | 18 patients (SCI) | Decompressive laminectomy + duraplasty | Improved ITP, SCPP, neuroplasticity markers |

| 2 | Phang et al., 2015 | Clinical - Observational | 25 patients (SCI) | Perfusion monitoring | Improved SCPP and pressure reactivity |

| 3 | Curt et al., 2008 | Clinical - Review | Variable (SCI) | NA | Neuroplasticity mechanisms |

| 4 | Kornblith et al., 2013 | Clinical - Multicenter | 150 patients (SCI) | Mechanical ventilation strategies | Improved extubation rates |

| 5 | Lenehan et al., 2012 | Clinical - Epidemiological | Population-based | NA | Epidemiological insights |

| 6 | Thietje et al., 2011 | Clinical - Retrospective | 62 patients (Deceased SCI) | Mortality analysis | Mortality and cause insights |

| 7 | Keefe et al., 2017 | Preclinical - Animal | Rodent models | Neurotrophic factor modulation | Increased BDNF, NGF levels |

| 8 | Stoyanova et al., 2021 | Preclinical - Animal | Rodent models | Ghrelin-mediated plasticity | Enhanced regeneration |

| 9 | Yue et al., 2020 | Clinical - Prospective | 35 patients (SCI) | Perfusion protocols | Enhanced functional recovery |

| 10 | Saadoun et al., 2020 | Clinical - Observational | 20 patients (SCI) | Targeted perfusion therapy | Reduced edema, improved outcomes |

| 11 | Leonard et al., 2015 | Preclinical - Animal | Rodent models | Substance P modulation | Reduced inflammation and edema |

| 12 | Punjani et al., 2023 | Preclinical - Review | Mixed human/animal data | Plasticity pathways | Highlighted neuroplasticity mechanisms |

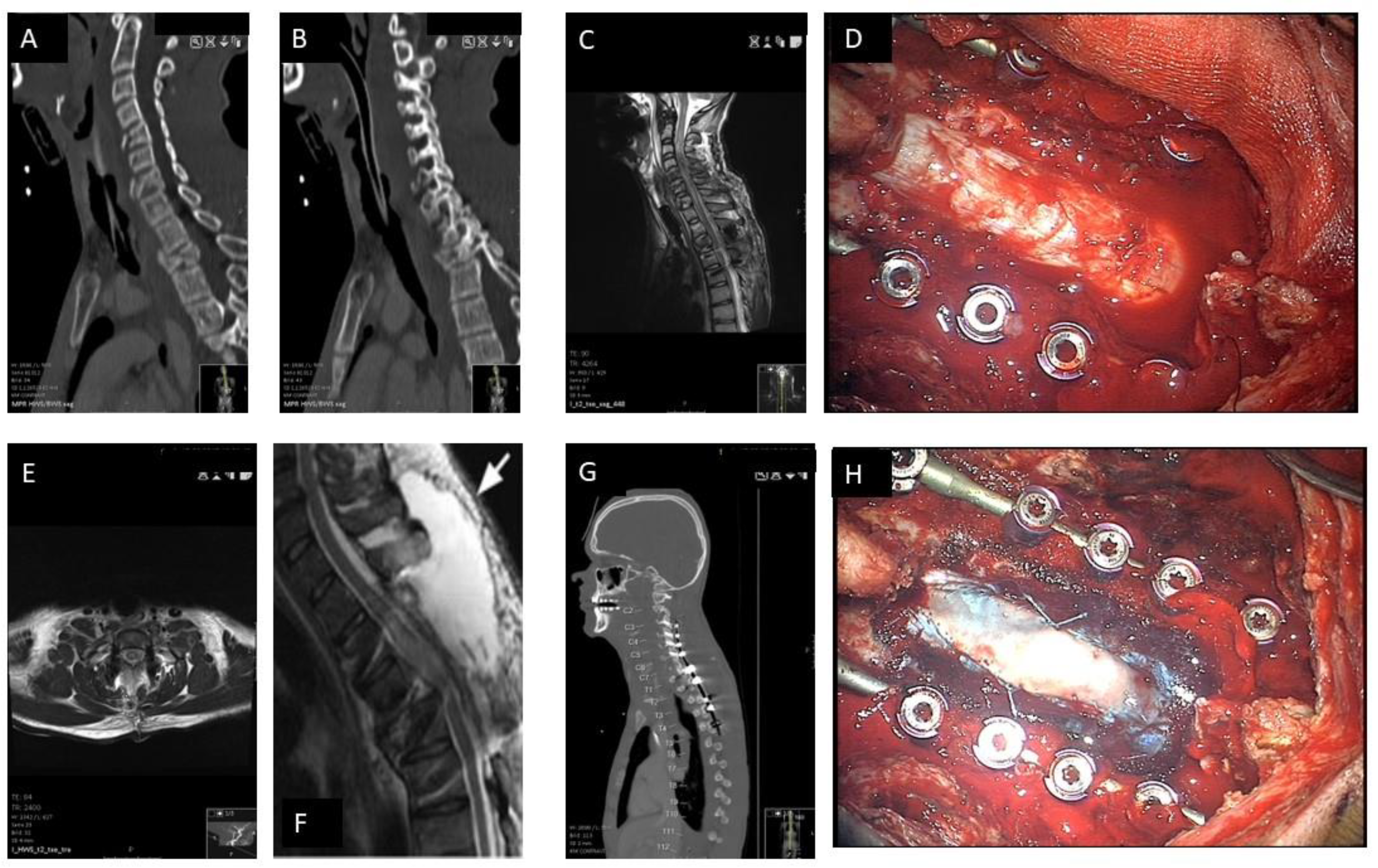

| 13 | Zhu et al., 2019 | Clinical - Retrospective | 30 patients (SCI) | Durotomy with duroplasty | Improved motor function and reduced intrathecal pressure |

| 14 | Ahuja et al., 2017 | Clinical - Systematic Review | Variable population (SCI) | Repair and regeneration strategies | Insights on neuroplasticity and axonal repair |

| 15 | Leonard et al., 2013 | Preclinical - Animal | Rodent models | Substance P modulation | Reduced inflammation and improved functional outcomes |

| 16 | Gotz et al., 2015 | Preclinical - Animal | Rodent models | Astrocytic plasticity interventions | Enhanced synaptic remodeling and axonal regeneration |

| 17 | Lau et al., 2011 | Preclinical - Animal | Lamprey brain models | Neurite sprouting post-SCI | Increased synapsin expression and sprouting |

| 18 | Anjum et al., 2020 | Clinical - Observational | 50 patients (SCI) | Inflammation-targeted therapies | Reduced secondary damage and improved recovery |

| 19 | Dimou and Gallo, 2015 | Preclinical - Review | Various animal models | NG2-glia functions | Insights into glial plasticity and neurogenesis |

| 20 | Guo et al., 2019 | Preclinical - Animal | Mouse models | Gene expression modulation | Identification of genes promoting regeneration |

| 21 | Bulsara et al., 2002 | Preclinical - Animal | Rodent models | Growth-associated genes | Enhanced axonal sprouting and plasticity |

| 22 | Cozzens et al., 2013 | Clinical - Systematic Review | Variable population (SCI) | Cervical spine and spinal cord injury management | Guidelines for early intervention |

| 23 | Zhong et al., 2023 | Preclinical - Animal | Rat models | PI3K/AKT signaling pathways | Improved axonal growth and synaptogenesis |

| 24 | Bobinger et al., 2018 | Preclinical - Review | Mixed models | Apoptotic pathways in neural injury | Insights on reducing cell death post-injury |

| 25 | Lee et al., 2010 | Preclinical - Animal | Rodent models | Ghrelin for apoptosis inhibition | Improved functional recovery |

| 26 | Le Feber et al., 2016 | Preclinical - In vitro | Neural cultures | Neuronal damage progression in ischemia | Modeling SCI-like ischemic conditions |

| 27 | Stoyanova et al., 2022 | Preclinical - Animal | Rodent models | Hypoxia-induced Pax6 modulation | Enhanced neuronal survival and regeneration |

| 28 | Galtrey and Fawcett, 2007 | Preclinical - Review | Mixed models | Role of CSPGs in regeneration | Reduction of inhibitory signaling |

| 29 | Saadoun et al., 2020 | Clinical - Observational | 25 patients (SCI) | Perfusion-targeted therapies | Reduced edema and improved SCPP |

| 30 | Sun et al., 2023 | Preclinical - Animal | Mouse models | Stem cells and exercise | Enhanced recovery via PI3K/AKT pathways |

| 31 | Grassner et al., 2018 | Clinical - Review | Variable population | Spinal meninges in SCI | Neuroanatomical insights into recovery |

| 32 | Phang et al., 2016 | Clinical - Retrospective | 20 patients (SCI) | Magnetic resonance imaging in perfusion monitoring | Improved spinal cord perfusion visualization |

| 33 | Miao et al., 2023 | Preclinical - Animal | Rodent models | Neuroplasticity via TrKA pathways | Enhanced neurite elongation and recovery |

| 34 | Werndle et al., 2014 | Clinical - Observational | 30 patients (SCI) | Perfusion pressure monitoring | Reduced secondary injury through SCPP improvements |

| 35 | Kwon et al., 2009 | Clinical - Randomized | 40 patients (SCI) | Intrathecal pressure monitoring | Improved outcomes via drainage protocols |

| 36 | Chen et al., 2017 | Preclinical - Animal | Rat models | BDNF signaling in synaptogenesis | Enhanced recovery of motor function |

| 37 | Varsos et al., 2015 | Clinical - Observational | 30 patients (SCI) | Spinal perfusion pressure dynamics | Reduced pressure-related damage |

| 38 | Leonard et al., 2015 | Preclinical - Animal | Rodent models | Edema and hemorrhage contributions | Reduction of post-injury complications |

| 39 | Fehlings et al., 2006 | Clinical - Systematic Review | Variable population (SCI) | Timing of intervention | Guidelines for early surgical decompression |

| 40 | Anjum et al., 2020 | Preclinical - Animal | Rodent models | Multi-molecular interactions post-SCI | Insights on recovery mechanisms |

| 41 | Gotz et al., 2015 | Preclinical - Animal | Rodent models | Reactive astrocyte modulation | Improved synaptic plasticity |

| 42 | Ahuja et al., 2017 | Clinical - Retrospective | 50 patients (SCI) | Surgical repair strategies | Improved outcomes via axonal repair |

| 43 | Saadoun et al., 2020 | Clinical - Observational | 20 patients (SCI) | Perfusion-targeted interventions | Improved SCPP and reduced edema |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).