0. How to Use This Template

The template details the sections that can be used in a manuscript. Note that each section has a corresponding style, which can be found in the “Styles” menu of Word. Sections that are not mandatory are listed as such. The section titles given are for articles. Review papers and other article types have a more flexible structure.

Remove this paragraph and start section numbering with 1. For any questions, please contact the editorial office of the journal or support@mdpi.com.

1. Introduction

Young human resources are a valuable asset for any society. Therefore, efforts to ensure mental health to develop an efficient workforce are among the primary topics of public health (Khezayi et al., 2023). One of the multiple factors threatening the mental health of youth and adolescents is aggression. In literary culture, aggression is defined as behavior aimed at harming others (Kilgore et al., 2021). This behavior is among the most common and costly behaviors (Krizan & Herlache, 2016). Aggression is recognized as one of the most prevalent behavioral problems during adolescence (Chen et al., 2020). According to a UNESCO survey, 32% of students experience physical violence (a type of aggression) annually, and this rate is increasing every year (Li et al., 2023). Aggressive behavior not only significantly spreads among peers (Rutger et al., 2021) but is also transmitted from one generation to the next (Oei et al., 2023), causing damage to various aspects of individuals’ lives, including career advancement (Moon et al., 2019; López & Extremera, 2021) and physical and mental health (Aguero, 2021). If individuals fail to manage this destructive characteristic, it can become the most expensive issue in mental health, burdening society through consequences such as delinquency and property damage (Young et al., 2019). Researchers have emphasized the importance of controlling and reducing aggression rates. To explore the various causes of aggression and methods for its control, scholars have studied different developmental stages and found that adolescence is a period marked by significant transformations in various areas. During this phase, individuals develop temperamental differences, such as reactions to the environment and the ability to control these responses (Kostarica, 2019). These characteristics predict a significant portion of an individual’s psychological adjustment (or maladjustment) and related vulnerabilities (Motahharnejad et al., 2021). These temperamental traits can either increase vulnerability to or protect against psychopathology (Nelson et al., 2019).

Neurobiological studies define alexithymia as the inability to differentiate between personal emotions and bodily sensations, a term first introduced by Sifneos (1973) (Falahatgar et al., 2023). Alexithymia is a multifaceted construct that is not considered a disorder but rather a personality trait. It manifests as difficulties in identifying and differentiating emotions from bodily sensations, describing emotions, a lack of imaginative and emotional inner life, outward-focused thinking, and avoidance of addressing serious conflicts (Çalah & Ayçe, 2017). In essence, alexithymia includes difficulties in recognizing emotions, expressing and describing emotions, and an external focus of thought. These traits reflect deficiencies in emotional regulation and cognitive processing (Davoodi-Boroujerd et al., 2023). Individuals with alexithymia often exhibit external behaviors, such as anger, violence, or other physical reactions, instead of employing internal mechanisms for emotional management (Hemel et al., 2024). Among children and adolescents, alexithymia is associated with externalizing behavioral problems (Manarini et al., 2016; Karukivi et al., 2010). Taylor et al. (1991) hypothesized that individuals with alexithymia might have a limited capacity for cognitively processing their emotions, leading to emotional suppression. Low emotional awareness (a component of alexithymia) is linked to the relationship between exposure to violence and psychological pathology (e.g., internalizing and externalizing problems) during adolescence (Weissman et al., 2020). In adulthood, alexithymia mediates relationships involving maltreatment, risky sexual behaviors (Hahn et al., 2015), impulsivity (Gaher et al., 2013), self-injurious behaviors (Paivio & McCulloch, 2004), and suicidal behaviors (Chen et al., 2020). The inability to comprehend and express emotions leads individuals to manifest negative feelings through negative social behaviors. In other words, the inability to regulate or express emotions can result in antisocial and aggressive behaviors (Hemel et al., 2024).

Research has also shown that in addition to the impact of alexithymia on students’ tendency toward aggression, one effective way to reduce such behaviors is positive parenting. Positive parenting is an educational approach based on fostering a loving and empathetic relationship between parents and children. In other words, this method emphasizes encouraging positive behaviors, strengthening effective communication, and nurturing children’s social, emotional, and cognitive abilities (Neppl et al., 2020).

Some key principles of positive p emotional and psychological needs (Prime et al., 2023). For example, Rahman et al. (2023) demonstrated that affectionate and supportive parenting methods can play a significant role in reducing destructive behaviors, aggression, and more in children.

Parents who help their children recognize and manage their emotions equip them with skills to cope with stressful situations (van Capellan et al., 2023). Positive parenting also fosters social skills such as empathy and cooperation, which can serve as alternatives to aggressive behaviors (Rahayu & Nurhayati, 2023). In summary, positive parenting employs strategies like encouraging emotional expression (Yang et al., 2022), teaching problem-solving skills, and responding appropriately to aggressive behaviors, all of which are effective in reducing aggression (Radmacher et al., 2023).

Parenting styles can have a direct impact on children’s emotional development. Parents who adopt positive parenting styles create a secure and supportive environment, helping their children recognize and express their emotions (Barberis et al., 2022). Parents who listen to their children’s emotions and encourage them to express themselves can prevent alexithymia in their children (Küçükoglu, 2024). Similarly, parents who clearly express their own emotions and manage their feelings in various situations serve as positive role models for their children (Tark Ladani & Aghababaei, 2022). In contrast, strict, inattentive, or neglectful parenting styles may contribute to the development of alexithymia in children. These children may grow up in environments where their emotions are either dismissed or criticized, hindering their emotional growth (Jansen et al., 2021). Positive parenting directly impacts the reduction of children’s aggressive behaviors by focusing on creating a warm and supportive relationship with them, rather than resorting to punishment or coercion. It aims to enhance self-esteem, reduce behavioral problems, and develop social and emotional skills (Yang et al., 2022).

Therefore, it can be expected that individuals raised under positive parenting are less prone to alexithymia and aggression compared to those who lack such parenting. Ultimately, positive parenting may serve as a moderator in the relationship between alexithymia and the tendency toward aggression during this sensitive developmental period. Given the above considerations, the present study aims to investigate the moderating role of positive parenting in the relationship between alexithymia and the tendency toward aggression in students and adolescents.

2. Materials and Methods

1.1. Study Design and Participants

The present study employed a descriptive-correlational research design. The statistical population included middle school students (grades 7–9) in Khorramabad city during the 2023–2024 academic year. The sample size was determined using Cochran’s formula, and 151 students were selected through multistage cluster sampling. Specifically, one educational district was randomly chosen from two districts, five schools were randomly selected from the chosen district, and 10 classes were then randomly selected from these schools. From the students in the selected classes, participants meeting the inclusion criteria were chosen. The inclusion criteria included: an age range of 12 to 15 years, willingness to participate, and the absence of psychiatric disorders or medication use. The exclusion criteria included unwillingness to cooperate or incomplete questionnaire responses. Ethical principles were strictly adhered to in this study, including confidentiality and respect for participants’ privacy. The data were analyzed using moderated hierarchical regression in SPSS26.

1.1. Measures

Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20)

The Toronto Alexithymia Scale is a 20-item questionnaire with three subscales: difficulty identifying feelings, difficulty describing feelings, and externally oriented thinking. The questionnaire is scored using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Items 1, 3, 6, 7, 9, 13, and 14 assess difficulty identifying feelings; items 2, 4, 11, 12, and 17 assess difficulty describing feelings; and items 5, 8, 10, 15, 16, 18, 19, and 20 assess externally oriented thinking. Scoring follows the Likert method: a score of 1 is assigned to “strongly disagree,” and a score of 5 to “strongly agree.” Items 4, 5, 10, 18, and 19 are reverse-scored, where “strongly disagree” receives a score of 5, and “strongly agree” receives a score of 1. Higher scores on the subscales indicate greater difficulty in recognizing and expressing emotions. The psychometric properties of the TAS-20 have been validated in numerous studies. Basharat and Ganji (2012) calculated Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.85 for the total scale, 0.82 for difficulty identifying feelings, 0.75 for difficulty describing feelings, and 0.72 for externally oriented thinking, demonstrating good internal consistency.

1.1.1. Anger and Aggression Scale

The Anger and Aggression Scale, developed by Nelson et al. (2000), is a 13-item self-report instrument. It evaluates various situations that lead to anger, the intensity of anger, and social skills in children aged 6 to 16 years. This questionnaire consists of four subscales: frustration, physical aggression, peer relationships, and authority relationships. Scoring is based on a 3-point Likert scale: “I don’t care,” “It bothers me,” and “I get really upset and angry.” The minimum possible score is 13, and the maximum is 39. To assess the validity and reliability of this scale, it was administered to 1,604 students. Results indicated test-retest reliability coefficients ranging from 0.65 to 0.75, internal consistency ranging from 0.85 to 0.86, and construct validity of 0.93 for the four subscales (Zibaei et al., 2013).

1.1.1. Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ)

The Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ) was developed by Frick in 1991. This questionnaire includes 42 items across five subscales and uses a 5-point Likert scale for scoring. Responses range from “never” (scored as 1) to “always” (scored as 5). To calculate the score for each subscale, the total score for its items is divided by the number of items to derive an average score. The five domains assessed by the APQ include: Parental Involvement: Items 1, 4, 7, 9, 11, 14, 15, 20, 23, and 26 Positive Parenting: Items 2, 5, 13, 16, 18, and 27 Inconsistent Discipline: Items 3, 8, 12, 22, 25, and 31 Poor Monitoring/Supervision: Items 6, 10, 17, 19, 21, 24, 28, 29, 30, and 32 Corporal Punishment: Items 33, 35, and 39 Samani (2011) assessed the construct validity of the APQ through factor analysis, which indicated suitable construct validity. The average correlation coefficients among the factors were 0.71, and the average correlation between the factors and the total APQ score was 0.55. Samani also reported Cronbach’s alpha reliability and test-retest reliability as 0.86, demonstrating strong psychometric properties for the scale in Iran.

1.1. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using the modified hierarchical regression method in SPSS26 software.

3. Results

Descriptive statistics of the studied variables are presented in

Table 1.

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was employed to assess the normality of the data distribution. Since the Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistic yielded a value greater than 0.05, the test results indicated a lack of significance, confirming the normality of the data distribution. Based on the research hypotheses, Pearson’s correlation coefficient test was used to examine the relationships between alexithymia, positive parenting, and aggression. The results of the analysis are presented in

Table 2.

The results in

Table 2 indicate that there is a significant correlation among all research variables. Additionally, to examine the moderating role of the variable positive parenting in the relationship between alexithymia and aggression, hierarchical regression analysis was employed. The results of this analysis are presented in

Table 3.

As shown in

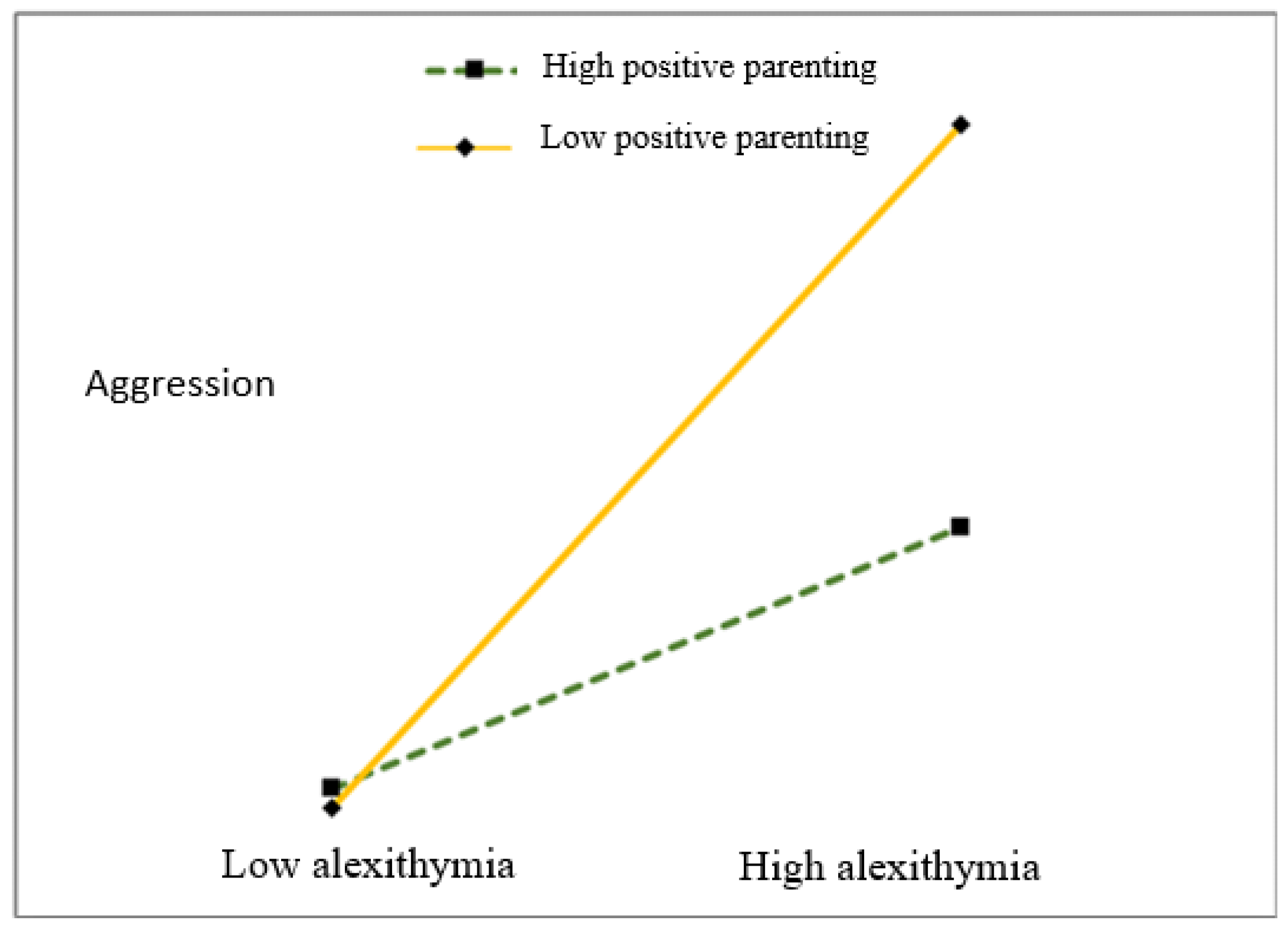

Table 3, the R² change test is significant. The values for emotional Alexithymia and positive parenting are 0.364 and 0.384, respectively. In the next step, with the inclusion of the interaction between the two variables, this value increases to 0.423, which is still significant. Therefore, positive parenting plays a moderating role in the relationship between emotional dysregulation and aggression tendencies. Based on the increase in the explained variance of aggression tendencies due to the inclusion of the interaction variable between emotional dysregulation and positive parenting, it can be concluded that positive parenting is capable of moderating the relationship between these two variables. In other words, emotional dysregulation and aggression tendencies differ at high and low levels of positive parenting. To clarify the nature of the moderating effect, the interaction plot was drawn using standardized regression coefficients, and the regression lines for high and low levels of positive parenting were plotted.

Figure 1 illustrates the interaction between emotional dysregulation and positive parenting in relation to aggression tendencies.

As shown in

Figure 1, aggression tendencies are at their highest for individuals with high emotional dysregulation and low positive parenting, and at their lowest for individuals with low emotional dysregulation and high positive parenting. Additionally, it is noticeable that high emotional dysregulation, when paired with low positive parenting, is associated with higher aggression tendencies compared to when it is paired with high positive parenting. Similarly, low emotional dysregulation, when combined with high positive parenting, is associated with lower aggression tendencies compared to when it is paired with low-positive parenting. Therefore, positive parenting plays a moderating role in the relationship between emotional dysregulation and aggression tendencies.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to examine the moderating role of positive parenting in the relationship between emotional dysregulation and aggression tendencies in adolescents. The results of the study revealed a significant positive relationship between emotional dysregulation and aggression tendencies, meaning that the higher the level of emotional dysregulation, the greater the tendency for aggression in adolescents.

These results are consistent with the findings of Hamel et al. (2024), Falahatgar et al. (2022), and Wiseman et al. (2020). In explaining these results, it should be noted that emotional dysregulation and aggression are significantly correlated, and this relationship is strengthened through mechanisms such as the inability to regulate emotions, decreased empathy, and chronic stress (Ahmadi Malayeri et al., 2022). However, with appropriate interventions, this vicious cycle can be broken, which could help improve social relationships and reduce aggressive behaviors (Chen et al., 2020). In summary, it has been stated that, among children and adolescents, emotional dysregulation is indeed associated with behavioral problems such as aggression (Mannarini et al., 2016; Karukivi et al., 2010).

In another part of the study, the results of hierarchical regression analysis showed that positive parenting plays a moderating role in the relationship between emotional dysregulation and aggression tendencies. In other words, the relationship between emotional dysregulation and aggression tendencies differs at high and low levels of positive parenting; specifically, a high level of positive parenting can reduce the relationship, while a low level of positive parenting can increase this relationship. The results of the present study are consistent with the findings of Yang et al. (2022), Rahman et al. (2023), Rahayu and Nourhiati (2023), and Kucukoglu (2024). In explaining the results of the studies, it has been briefly stated that positive parenting can be related to reduced aggression in children, in such a way that positive parenting, by helping children learn emotion regulation skills, allows them to use more peaceful methods instead of aggressive reactions in stressful or anger-inducing situations (Jansen et al., 2021). Furthermore, positive parenting, by modeling non-aggressive behaviors and strengthening emotional connections, helps children adopt healthier behavioral patterns. Ultimately, the presence of supportive and responsive parents increases the child’s sense of psychological security and reduces the likelihood of aggressive behaviors (Tark Ladani and Aqababai, 2022). As a result, positive parenting has a significant impact on reducing aggressive behaviors. Additionally, as mentioned, parenting styles play a significant role in the emotional development of children. According to the findings of Barberis et al. (2022), parents using positive parenting methods help their children identify and express their emotions by creating a safe and supportive environment. Similarly, Kucukoglu’s (2024) research shows that parents who attend to their children’s emotions and encourage them to express their feelings can prevent the development of emotional dysregulation in children. Every study has limitations, and the present study is no exception. Some of the limitations of this study include individual differences among participants, such as their level of motivation and interest in the subject, which may have influenced the results. Moreover, the self-report instruments used in this study have limitations, such as social desirability bias, which may have impacted the accuracy of the collected data.

5. Conclusions

Furthermore, this study was conducted with students from the city of Khorramabad, so generalizing the results to other populations should be done with caution. Despite these limitations, the findings of the study showed that positive parenting plays a key role in reducing adolescents’ tendencies toward aggression. Therefore, teaching skills related to positive parenting can help adolescents improve their relationships with parents and manage their behavioral self-regulation during adolescence, thereby reducing the likelihood of aggressive behaviors. These findings may have practical applications for child, adolescent, and family counselors and psychologists.

Author Contributions

MA: concept, design, definition of intellectual content, manuscript editing, and manuscript review. MA: literature search, data acquisition, data analysis, manuscript preparation, manuscript editing, and manuscript review. MA: data analysis, statistical analysis, manuscript preparation, manuscript editing, and manuscript review. MHN and MA: manuscript editing and manuscript review.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study adhered to ethical research principles. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, ensuring voluntary participation, confidentiality, and the right to withdraw at any time. While formal ethics approval from an institutional review board was not required for this research, all procedures followed ethical guidelines for studies involving human participants.

Informed Consent Statement

We affirm that this work is original and has not been published elsewhere, except as noted in the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the students and schools that participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

References

- Aguero, J. M. (2021). COVID-19 and the rise of intimate partner violence. World Development, 137, 105217. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi-Molaeri, G. , Rahmani, M. A., & Pour-Asghar, M. (2022). The effectiveness of compassion-focused therapy on alexithymia and aggression in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Islamic Lifestyle Centered on Health, 6(4), 88–98. Retrieved from https://sid.ir/paper/1117086/fa.

- Barberis, N. , Cannavò, M., Cuzzocrea, F., & Verrastro, V. (2022). Alexithymia in a Self Determination Theory Framework: The interplay of Psychological Basic Needs, Parental Autonomy Support and Psychological Control. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 32(9), 2652–2664. [CrossRef]

- Besharat, M. , & Ganji, P. (2012). The moderating role of attachment styles in the relationship between emotional alexithymia and marital satisfaction. Journal of Principles of Mental Health, 14(56), 35 324. [CrossRef]

- Buades-Rotger, M. , Göttlich, M., Weiblen, R., Petereit, P., Scheidt, T., Keevil, B. G., & Krämer, U. M. (2021). Low competitive status elicits aggression in healthy young men: behavioural and neural evidence. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 16(11), 1123–1137. [CrossRef]

- Chalah, M. A. , & Ayache, S. S. (2017). Alexithymia in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review of literature. Neuropsychologia, 104, 31–47. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. , Zhang, C., Wang, Y., & Xu, W. (2020). A longitudinal study of inferiority impacting on aggression among college students: The mediation role of cognitive reappraisal and expression suppression. Personality and Individual Differences, 157, 109839. [CrossRef]

- Davoodi-Boroujerd, G. , Abbasi, E., Masjedi-Arani, A., & Asalzaker, M. (2022). The relationship between maternal personality and internalizing/externalizing behaviors: The mediating role of children’s alexithymia and emotion regulation. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, 17(1), 61–71. Retrieved from https://sid.ir/paper/976125/fa.

- Falahatgar-Ooshibi, P. , Hami, M., & Shojaei, V. (2022). The moderating role of electronic sports on the effect of alexithymia and aggression in high school students. Organizational Behavior Management in Sport Studies, 9(3), 11–27. [CrossRef]

- Frick, P. J. (1991). Alabama Parenting questionnaire [Dataset]. In PsycTESTS Dataset. [CrossRef]

- Gaher, R. M. Gaher, R. M., Arens, A. M., & Shishido, H. (2013). Alexithymia as a mediator between childhood maltreatment and impulsivity. Stress and Health, 31(4), 274–280. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, A. M. , Simons, R. M., & Simons, J. S. (2015). Childhood Maltreatment and Sexual risk taking: The Mediating role of Alexithymia. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(1), 53–62. [CrossRef]

- Hamel, C. , Rodrigue, C., Clermont, C., Hébert, M., Paquette, L., & Dion, J. (2024). Alexithymia as a mediator of the associations between child maltreatment and internalizing and externalizing behaviors in adolescence. Scientific Reports, 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Jansen, E. , Thapaliya, G., Aghababian, A., Sadler, J., Smith, K., & Carnell, S. (2021). Parental stress, food parenting practices and child snack intake during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appetite, 161, 105119. [CrossRef]

- Karukivi, M. , Hautala, L., Kaleva, O., Haapasalo-Pesu, K., Liuksila, P., Joukamaa, M., & Saarijärvi, S. (2010). Alexithymia is associated with anxiety among adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 125(1–3), 383–387. [CrossRef]

- Khazaee, H. , Hamzeh, B., Najafi, F., Chehri, A., Rahimi-Moghadam, A., Amin-Esmaeili, M., Moradi-Nazar, M., Zakiyee, A., & Pasdar, Y. (2023). Co-occurrence of aggression and suicide attempts among youth and associated factors: Findings from the Iranian Youth Cohort Study in Ravansar. Archives of Iranian Medicine, 26(6), 322–329. [CrossRef]

- Killgore, W. D. , Cloonan, S. A., Taylor, E. C., Anlap, I., & Dailey, N. S. (2021). Increasing aggression during the COVID-19 lockdowns. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 5, 100163. [CrossRef]

- Kostyrka-Allchorne, K. , Wass, S. V., & Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S. (2019). Research Review: Do parent ratings of infant negative emotionality and self-regulation predict psychopathology in childhood and adolescence? A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective longitudinal studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 61(4), 401–416. [CrossRef]

- Krizan, Z. , & Herlache, A. D. (2016). Sleep disruption and aggression: Implications for violence and its prevention. Psychology of Violence, 6(4), 542–552. [CrossRef]

- Küçükoğlu, S. (2024). The impact of parental attitudes on alexithymia in children with chronic diseases. Journal of Psychiatric Nursing, 305–315. [CrossRef]

- Li, S. , Wu, Z., Zhang, Y., Xu, M., Wang, X., & Ma, X. (2023). Internet gaming disorder and aggression: A meta-analysis of teenagers and young adults. Frontiers in Public Health, 11. [CrossRef]

- Mannarini, S., Balottin, L., Toldo, I., & Gatta, M. (2016). Alexithymia and psychosocial problems among Italian preadolescents. A latent class analysis approach. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 57(5), 473–481. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, S. , Dobson, R., & Maddison, R. (2020). The relationship between household chaos and child, parent, and family outcomes: a systematic scoping review. BMC Public Health, 20(1). [CrossRef]

- Mérida-López, S. , & Extremera, N. (2021). Student aggression against teachers, stress, and emotional intelligence as predictors of withdrawal intentions among secondary school teachers. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping/Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 35(3), 365–378. [CrossRef]

- Moon, B. , McCluskey, J., & Morash, M. (2019).Aggression against middle and high school teachers: Duration of victimization and its negative impacts. Aggressive Behavior, 45(5), 517–526. [CrossRef]

- Motahhar-Nejad, E. , Kadivar, P., Karamati, H., & Arabzadeh, M. (2021). Factor structure, validity, and reliability of the Effortful Control Scale (ECS) among Iranian adolescents. Retrieved from http://noo.rs/wXZbp.

- Nelson W, Finch A. Children inventory for angry: Manual. LosAngeles, CA: Western Psychological Service. 2000.1-5 https://search.worldcat.org/title/Children’s-inventory-of-anger-:-ChIA-manual/oclc/48262546.

- Neppl, T. K., Jeon, S., Diggs, O., & Donnellan, M. B. (2020). Positive parenting, effortful control, and developmental outcomes across early childhood. Developmental Psychology, 56(3), 444–457. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J. D. , Olino, T. M., Dyson, M. W., & Klein, D. N. (2019). Reactive and Regulatory Temperament: Longitudinal Associations with Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms through Childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(11), 1771–1784. [CrossRef]

- Oei, A. , Li, D., Chu, C. M., Ng, I., Hoo, E., & Ruby, K. (2023). Disruptive behaviors, antisocial attitudes, and aggression in young offenders: Comparison of Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) typologies. Child Abuse & Neglect, 141, 106191. [CrossRef]

- Paivio, S. C. , & McCulloch, C. R. (2004). Alexithymia as a mediator between childhood trauma and self-injurious behaviors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(3), 339–354. [CrossRef]

- Prime, H. , Andrews, K., Markwell, A., Gonzalez, A., Janus, M., Tricco, A. C., Bennett, T., & Atkinson, L. (2023). Positive Parenting and Early Childhood Cognition: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 26(2), 362–400. [CrossRef]

- Rademacher, A. , Zumbach, J., & Koglin, U. (2023). Parenting Style and Child Aggressive Behavior from Preschool to Elementary School: The Mediating Effect of Emotion Dysregulation. Early Childhood Education Journal. [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, S. , & Nurhayati, S. (2023). Implementation of positive parenting in early childhoods’ families during the Learning From Home program. Jurnal Simki Pedagogia, 6(2), 512–519. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, F., Maqbool, S., Ali, A., Mahmud, T., Azhar, H., & Farid, A. (2023). Parenting practices and aggression in childhood behaviour disorders. Pakistan Armed Forces Medical Journal, 73(1), 74–78. [CrossRef]

- Samani, S. , Kheir, M., & Sedaghat, Z. (2011). Parenting styles in various family types in the family process and content model. Family Research Quarterly, 6(22), 162–165, Retrieved from https://www.sid.ir/paper/122585/fa.

- Tark-Ladani, S. , & Aghababaei, S. (2022). The effectiveness of positive parenting training on parent-child interaction and behavioral problems of children with externalizing problems. Exceptional Children (Research on Exceptional Children), 22(3), 123–134, Retrieved from https://sid.ir/paper/1060590/fa.

- Taylor, G. J. , Bagby, R. M., & Parker, J. D. (1991). The Alexithymia Construct: A Potential Paradigm for Psychosomatic Medicine. Psychosomatics, 32(2), 153–164. [CrossRef]

- Van Cappellen, S. M. , Kühl, E., Schuiringa, H. D., Matthys, W., & Van Nieuwenhuijzen, M. (2023). Social information processing, normative beliefs about aggression and parenting in children with mild intellectual disabilities and aggressive behavior. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 136, 104468. [CrossRef]

- Weissman, D. G. , Nook, E. C., Dews, A. A., Miller, A. B., Lambert, H. K., Sasse, S. F., Somerville, L. H., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2020). Low emotional awareness as a transdiagnostic mechanism underlying psychopathology in adolescence. Clinical Psychological Science, 8(6), 971–988. [CrossRef]

- Yang, P. , Schlomer, G. L., & Lippold, M. A. (2022). Mothering versus fathering? Positive parenting versus negative parenting? Their relative importance in predicting adolescent aggressive behavior: A longitudinal comparison. Developmental Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Young, A. S. , Youngstrom, E. A., Findling, R. L., Van Eck, K., Kaplin, D., Youngstrom, J. K., Calabrese, J., Stepanova, E., & Consortium, N. L. (2019). Developing and validating a definition of Impulsive/Reactive Aggression in Youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 49(6), 787–803. [CrossRef]

- Zibaei, E. , Gholami, H., Zare, M., Mahdian, H., Yavari, M., & Harathabadi, M. (2013). The effect of offline training on anger management in teenage girls in Mashhad middle schools. Journal of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, 5(2), 375–385, Retrieved from http://journal.nkums.ac.ir/article-1-75-fa.html.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).