Submitted:

12 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

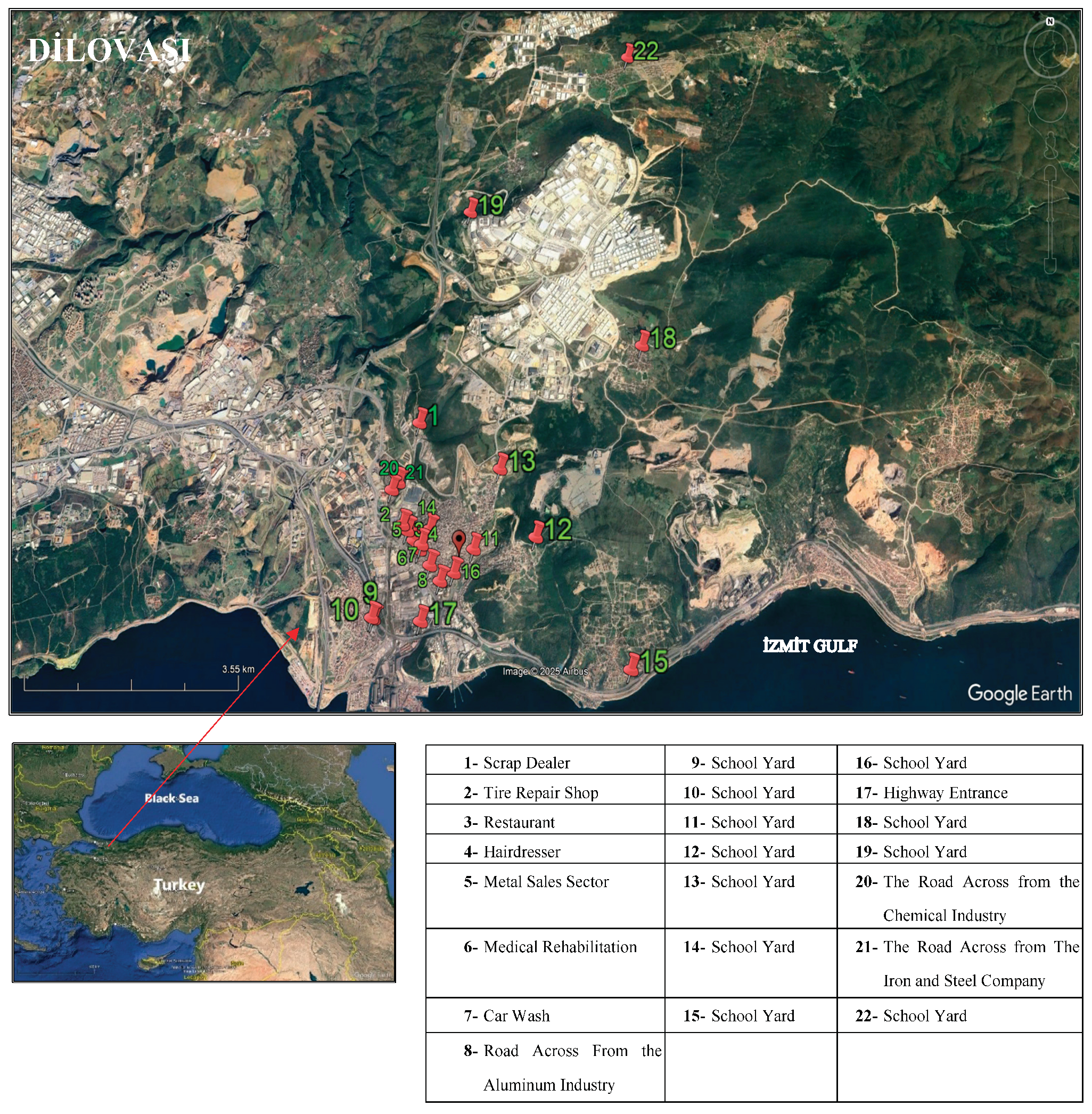

2.1. Sampling and Analysis

2.3. Distribution Maps

2.4. Health Risk Assessment

3. Results and Discussion

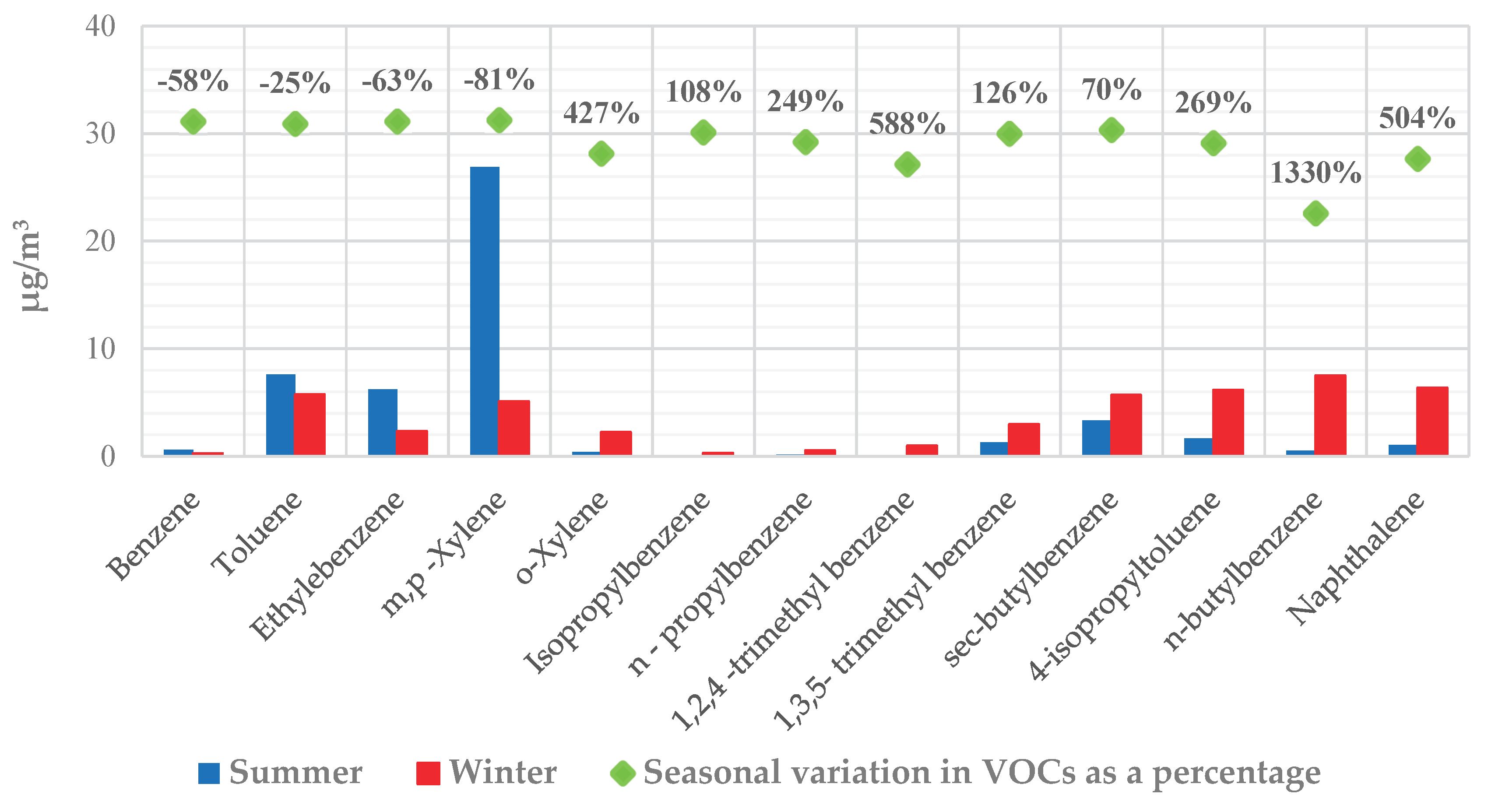

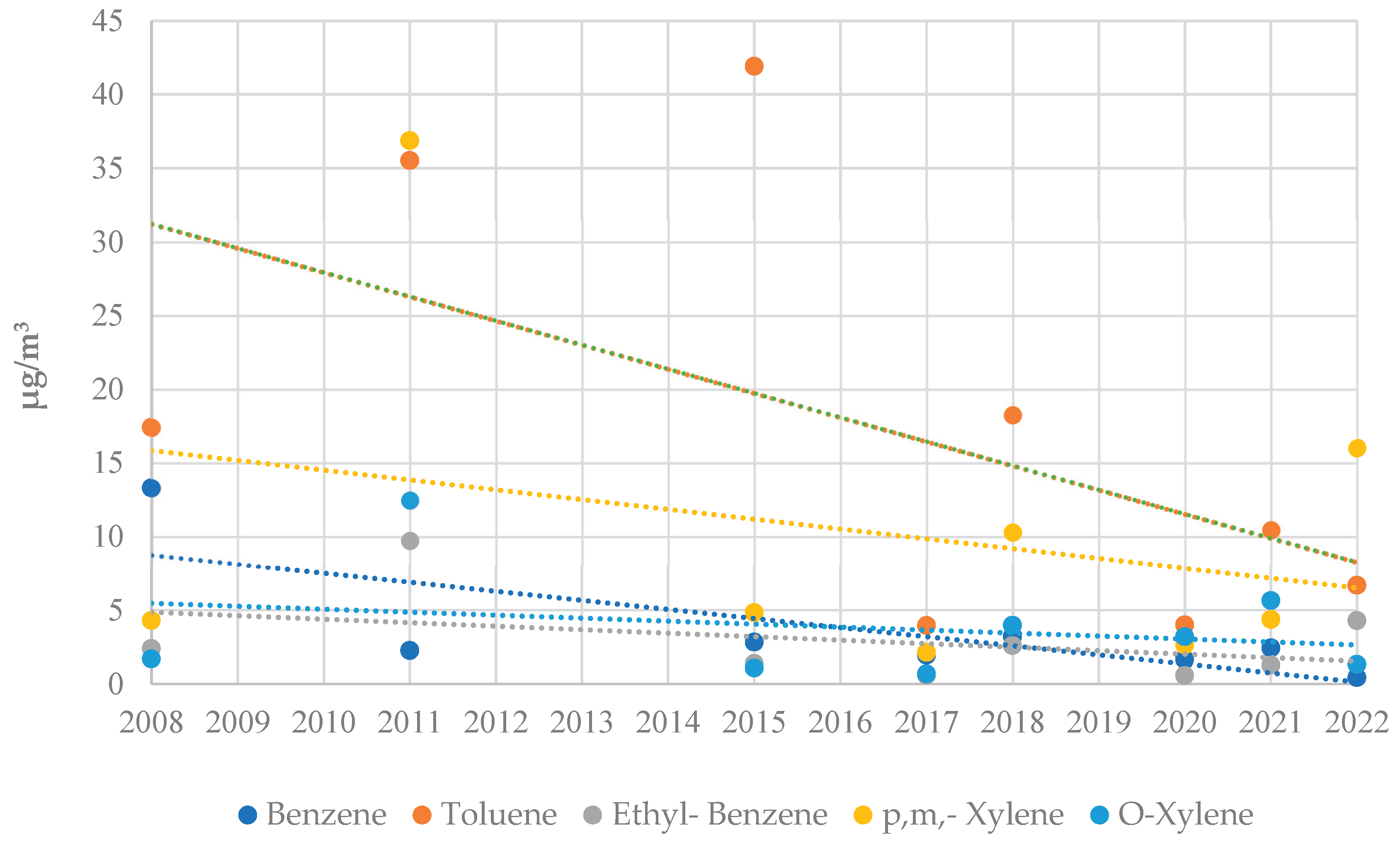

3.1. Concentration of VOC in the Ambient Air

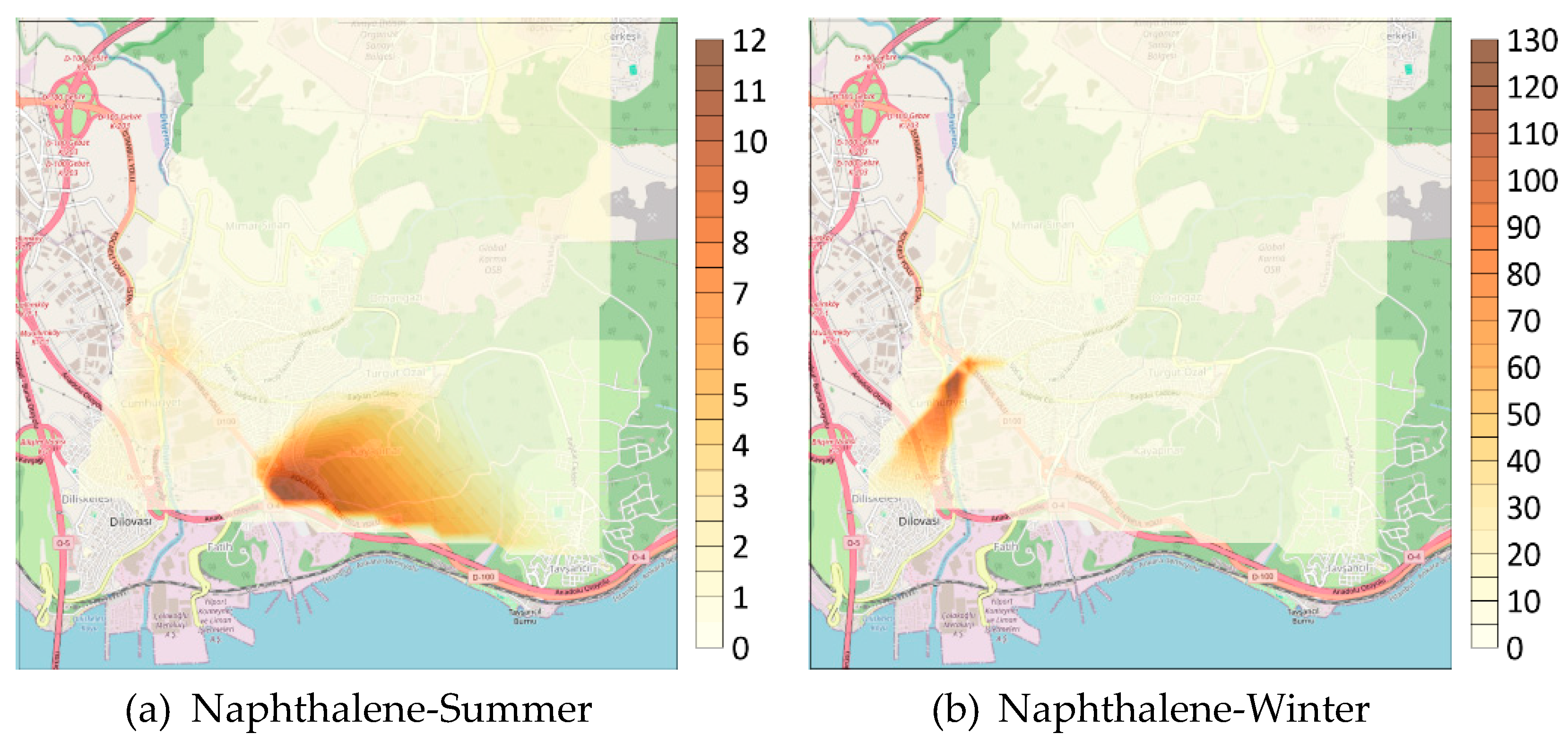

3.2. Spatial Analysis of BTEX and Naphthalene

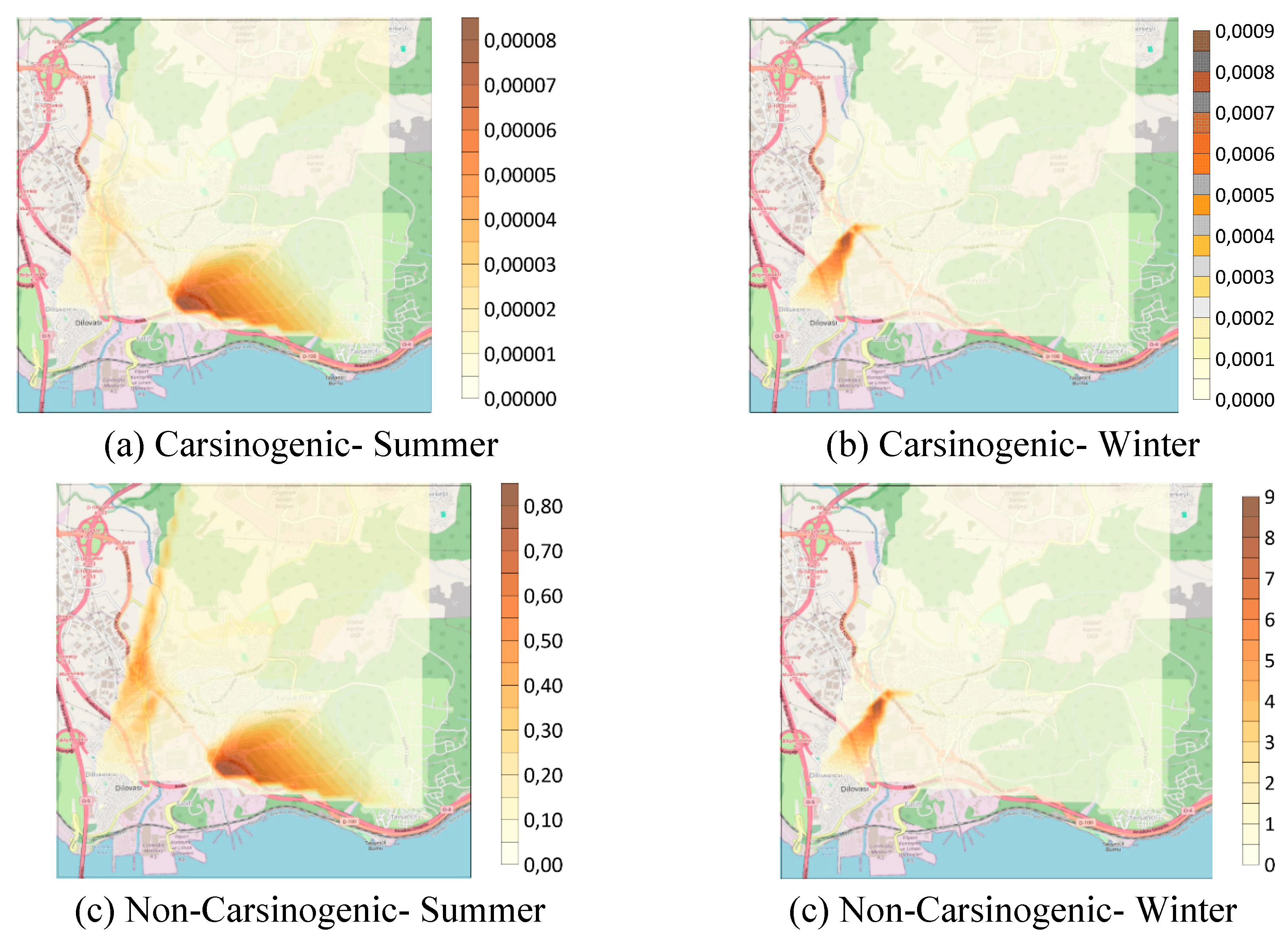

3.3. Health Risk Assessment of VOCs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BTEX | Benzene, Toluene, Ethyl Benzene, And Xylene; |

| CPF | The Carcinogenic Potency Factor Or Cancer Slope Factor; |

| HAPs | Hazardous Air Pollutants; |

| HI | Hazard Index; |

| HQ | Hazard Quotient; |

| IARC | the International Agency for Research on Cancer; |

| ILTCR | Integrated Life Time Cancer Risk; |

| LNG | Liquefied Natural Gas; |

| NIST | The National Institute of Standards and Technology; |

| RAIS | Risk Assessment Information System; |

| RfC | Reference Concentration; |

| SITARC | Scientific Industrial and Technological Applications and Research Center; |

| US EPA | U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; |

| VOCs | Volatile Organic Compounds; |

References

- Moolla, R.; Curtis, C. J.; Knight, J. Assessment of occupational exposure to BTEX compounds at a bus diesel-refueling bay: A case study in Johannesburg, South Africa. Science of the Total Environment. 2015, 537, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S. J.; Lee, S. J.; Hong, Y.; Choi, S. D. Investigation of priority anthropogenic VOCs in the large industrial city of Ulsan, South Korea, focusing on their levels, risks, and secondary formation potential. Atmospheric Environment. 2025, 343, 120982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, R.; Li, M.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Xue, L.; Hou, K. Pollution investigation of wintertime VOCs in the coastal atmosphere of the Yellow Sea: Insights from on-line photoionization-induced CI-TOFMS. Science of the Total Environment. 2024, 957, 177568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, S.; Yoon, S.; Erickson, M. H.; Guo, F.; Mehra, M.; Bui, A. A. T.; Schulze, B. C.; Kotsakis, A.; Daube, C.; Herndon, S. C.; Yacovitch, T. I.; Alvarez, S.; Flynn, J. H.; Griffin, R. J.; Cobb, G. P.; Usenko, S.; Sheesley, R. J. Traffic, transport, and vegetation drive VOC concentrations in a major urban area in Texas. Science of the Total Environment. 2022, 838, 155861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Baghel, N.; Lakhani, A.; Kumari, K. M. BTEX and formaldehyde levels at a suburban site of Agra: Temporal variation, ozone formation potential and health risk assessment. Urban Climate. 2021, 40, 100997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masih, A.; Lall, A. S.; Taneja, A.; Singhvi, R. Inhalation exposure and related health risks of BTEX in ambient air at different microenvironments of a terai zone in north India. Atmospheric Environment. 2016, 147, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazrati, S.; Rostami, R.; Farjaminezhad, M.; Fazlzadeh, M. Preliminary assessment of BTEX concentrations in indoor air of residential buildings and atmospheric ambient air in Ardabil, Iran. Atmospheric Environment. 2016, 132, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beba, H.; Öztürk, Z. Investigation of models predicting NOx level in the sample region and the use of intelligent transportation system. Environmental Challenges. 2024, 16, 100990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurdakul, S.; Çelik, I.; Çelen, M.; Öztürk, F.; Cetin, B. Levels, temporal/spatial variations and sources of PAHs and PCBs in soil of a highly industrialized area. Atmospheric Pollution Research. 2019, 10(4), 1227–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, B.; Yurdakul, S.; Odabasi, M. Spatio-temporal variations of atmospheric and soil polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in highly industrialized region of Dilovasi. Science of the Total Environment. 2019, 646, 1164–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, B.; Yurdakul, S.; Gungormus, E.; Ozturk, F.; Sofuoglu, S. C. Source apportionment and carcinogenic risk assessment of passive air sampler-derived PAHs and PCBs in a heavily industrialized region. Science of the Total Environment. 2018, 633, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yolcubal, I.; Gündüz, Ö. C.; Sönmez, F. Assessment of impact of environmental pollution on groundwater and surface water qualities in a heavily industrialized district of Kocaeli (Dilovası), Turkey. Environmental Earth Sciences. 2016, 75(2), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, N.; Ergenekon, P.; Seçkin, G. Ö.; Bayir, S. Spatial distribution and temporal trends of VOCs in a highly industrialized town in Turkey. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 2015, 94(5), 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingöl, D.; Ay, Ü.; Karayünlü Bozbaş, S.; Uzgören, N. Chemometric evaluation of the heavy metals distribution in waters from the Dilovasi region in Kocaeli, Turkey. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2013, 68, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekey, B.; Yilmaz, H. The use of passive sampling to monitor spatial trends of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) at an industrial city of Turkey. Microchemical Journal. 2011, 97(2), 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbay, B.; Keskin, G. A.; Doǧruparmak, Ş. Ç.; Ayberk, S. Multivariate methods for ground-level ozone modeling. Atmospheric Research 2011, 102, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaylali-Abanuz, G. Heavy metal contamination of surface soil around Gebze industrial area, Turkey. Microchemical Journal. 2011, 99(1), 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergenekon, P.; Öztürk, N. K.; Tavşan, S. Environmental air levels of volatile organic compounds by thermal desorption-gas chromatography in an industrial region envıronmental aır levels of volatıle organıc compounds by thermal desorp-tıon-gas chromatography ın an ındustrıal regıon. Fresenius Environmental Bulletin. 2009, 18, 1999–2003. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289221960.

- Population, Dilovası Population, Retrieved March 31, 2025. https://www.nufusu.com/ilce/dilovasi_kocaeli-nufusu.

- Google Earth, Retrieved January 15, 2024. https://earth.google.com/.

- Lakestani, S. Volatile organic compounds and cancer risk assessment in an intensive care unit. International Journal of Biometeorology. 2024, 68, 1731–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compendium Method TO-17, Determination of Volatile Organic Compounds in Ambient Air Using Active Sampling Onto Sorbent Tubes, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, EPA. Retrieved February 20, 2025. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2019-11/documents/to-17r.pdf.

- Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS), IRIS Agenda, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, EPA. Washington, DC. Retrieved February 20, 2025. https://www.epa.gov/iris/iris-agenda.

- Risk Assessment Information System [RAIS], Toxicity Profile, 2010. Retrieved February 20. https://rais.ornl.gov/tools/tox_profiles.html.

- Tunsaringkarn, T.; Siriwong, W.; Rungsiyothin, A.; Nopparatbundit, S. Occupational exposure of gasoline station workers to BTEX compounds in Bangkok, Thailand. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine The College of Public Health Sciences, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand. tkalayan@chula.ac.th. 2012, 3, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, T. K.; Yadav, P.; Kumar, M.; Lal, S.; Soni, K.; Yadav, L.; Saharan, U. S.; Sharma, S. K. Characteristics of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) at an urban site of Delhi, India: Diurnal and seasonal variation, sources apportionment. Urban Climate. 2023, 49, 101545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S. A.; Abtahi, M.; Dobaradaran, S.; Hassankhani, H.; Koolivand, A.; Saeedi, R. Assessment of health risk and burden of disease induced by exposure to benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene in the outdoor air in Tehran, Iran. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2023, 30(30), 75989–76001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshakhlagh, A.S.; Yazdanirad, S.; Mousavi, M.; Gruszecka-Kosowska, A.; Shahriyari, M.; Rajabi-Vardanjani, H. Summer and winter variations of BTEX concentrations in an oil refinery complex and health risk assessment based on Monte-Carlo simulations. Scientific Reports 2023, 12, 10670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raysoni, A. U.; Pinakana, S. D.; Luna, A.; Mendez, E.; Ibarra-Mejia, G. Characterization of BTEX species at Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) Continuous Ambient Monitoring Station (CAMS) sites in Houston, Texas, USA during 2018. Sustainable Chemistry for the Environment. 2025, 9, 100227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauri, N.; Bauri, P.; Kumar, K.; Jain, V.K. Evaluation of seasonal variations in abundance of BTXE hydrocarbons and their ozone forming potential in ambient urban atmosphere of Dehradun (India). Air Quality, Atmosphere and Health 2016, 9, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distribution of Registered Cars According to Fuel Type, Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved February 20, 2025. https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Motorlu-Kara-Tasitlari-Nisan-2024-53456#:~:text=Nisan%20ay%C4%B1%20sonu%20itibar%C4%B1yla%20trafi%C4%9Fe%20kay%C4%B1tl%C4%B1%2015%20milyon%20562%20bin,%250%2C2.

- Singh, R.; Gaur, M.; Shukla, A. Seasonal and Spatial Variation of BTEX in Ambient Air of Delhi. Journal of Environmental Protection. 2016, 7, 670–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastavaa, A.; Josepha, A.E.; Devottab, S. Volatile organic compounds in ambient air of Mumbai—India. Atmospheric Environment 2006, 40, 892–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traffic Flow Characteristics and Traffic Parameters of State Roads, Ministry of Transport, General Directorate of Highways, 2009. Retrieved March 10, 2025 https://www.kgm.gov.tr/SiteCollectionDocuments/KGMdocuments/Yayinlar/YayinPdf/Devlet%20Yollar%C4%B1%20Trafik%20Ak%C4%B1m%C4%B1%20%C3%96zellikleri%20ve%20Trafik%20Parametreleri.pdf.

- Mullaugh, K.M.; Hamilton, J.M.; Avery, G.B.; Felix, J.D.; Mead, R.N.; Willey, J.D.; Kieber, R.J. Temporal and spatial variability of trace volatile organic compounds in rainwater. Chemosphere. 2015, 134, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekey, H.; Pekey, B.; Arslanbas, D.; Bozkurt, Z.; Dogan, G.; Tuncel, G. Source identification of volatile organic compounds and particulate matters in an urban and industrial areas of Turkey. Ekoloji. 2015, 24(94), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, B.; De, M.; Rout, T. K.; Padhy, P. K. Study on spatiotemporal distribution and health risk assessment of BTEX in urban ambient air of Kolkata and Howrah, West Bengal, India: Evaluation of carcinogenic, non-carcinogenic and additional leukaemia cases. Atmospheric Pollution Research 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T. H.; Lin, C.; Nguyen, D. H.; Cheruiyot, N. K.; Yuan, C. S.; Hung, C. H. Volatile organic compounds in ambient air of a major Asian port: spatiotemporal variation and source apportionment. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2023, 30, 28718–28729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legislation information system of the Republic of Turkey, National Air Quality Assessment and Management Regulation, Date 09/09/13 and Number 31677. Retrieved April 20, 2025. https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?MevzuatNo=12188&MevzuatTur=7&MevzuatTertip=5.

- Buckpitt, A.; Kephalopoulos, S.; Koistinen, K.; Kotzias, D.; Morawska, L.; Sagunski, H. Naphthalene. In: WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: Selected Pollutants. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2010. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK138704/.

| Compound | CPF (1/(mg.kg.day)) | RfC (mg/m3) |

|---|---|---|

| Benzene | 2.73 x 10-2 | 0.03 |

| Toluen | NA | 5 |

| Etylbenzene | 3.85 x 10-3 | 1 |

| m,p-xylene | NA | 0.1 |

| o-xylene | NA | 0.1 |

| Isopropylbenzene | NA | 0.4 |

| n-propylbenzene | NA | NA |

| 1,2,4-trimetylbenzene | NA | 0.2 |

| 1,3,5-trimetylbenzene | NA | 0.2 |

| Sec-butylbenzene | NA | NA |

| 4-isopropyltoluen | NA | NA |

| n-butylbenzene | NA | NA |

| Napthalene | 1.19 x 10-1 | 0.003 |

| Exposure Parameters | ||

| IR (inhalation rate for adults) | 0.83 m3/h | |

| ED (exposure duration for adults) | 24 h/day | |

| BW (body weigh for adult) | 70 kg | |

| D (days per week exposure) | 7 days | |

| WK (weeks of exposure) | 52 weeks | |

| YE (years of exposure for adults) | 15 years | |

| YL (years in lifetime for adults) | 75 years | |

| Station Number | Average | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T/B | X/E | B/T | X/B | |

| 1 | 33,152 | 4,619 | 0,030 | 20,475 |

| 2 | 12,038 | 3,368 | 0,083 | 32,534 |

| 3 | 26,309 | 3,962 | 0,038 | 26,118 |

| 4 | 5,684 | 4,299 | 0,176 | 39,514 |

| 5 | 94,929 | 5,226 | 0,011 | 65,164 |

| 6 | 9,821 | 4,053 | 0,102 | 96,166 |

| 7 | 3,140 | 4,401 | 0,319 | 8,193 |

| 8 | 1,522 | 5,827 | 0,657 | 5,633 |

| 9 | 6,129 | 5,749 | 0,163 | 20,228 |

| 10 | 8,703 | 4,515 | 0,115 | 12,116 |

| 11 | 3,808 | 5,453 | 0,263 | 3,853 |

| 12 | 8,698 | 5,296 | 0,115 | 6,020 |

| 13 | 7,559 | 4,115 | 0,132 | 60,626 |

| 14 | 10,836 | 4,777 | 0,092 | 12,601 |

| 15 | 3,958 | 5,752 | 0,253 | 12,805 |

| 16 | 27,598 | 3,495 | 0,036 | 38,036 |

| 17 | 12,804 | 4,663 | 0,078 | 13,801 |

| 18 | 3,804 | 4,770 | 0,263 | 6,183 |

| 19 | 13,543 | 5,250 | 0,074 | 13,034 |

| 20 | 34,367 | 4,247 | 0,029 | 314,851 |

| 21 | 33,684 | 4,549 | 0,030 | 53,525 |

| 22 | 7,538 | 5,318 | 0,133 | 10,290 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).