Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Genetic Analysis

2.2.1. mtDNA Control Region and Nuclear LDH-C1

2.2.2. Genomic Analysis

3. Results

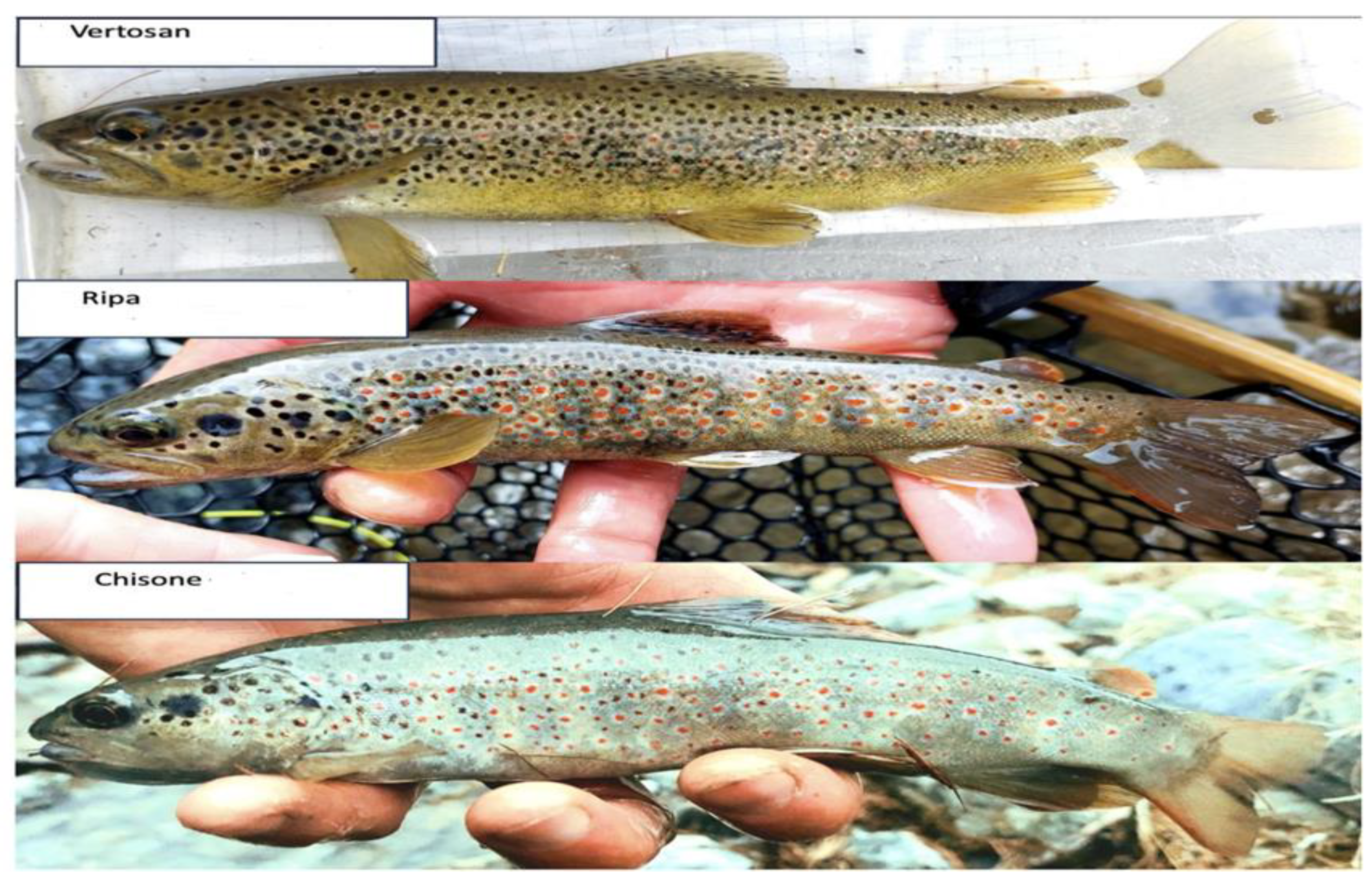

3.1. Animal Genotyping

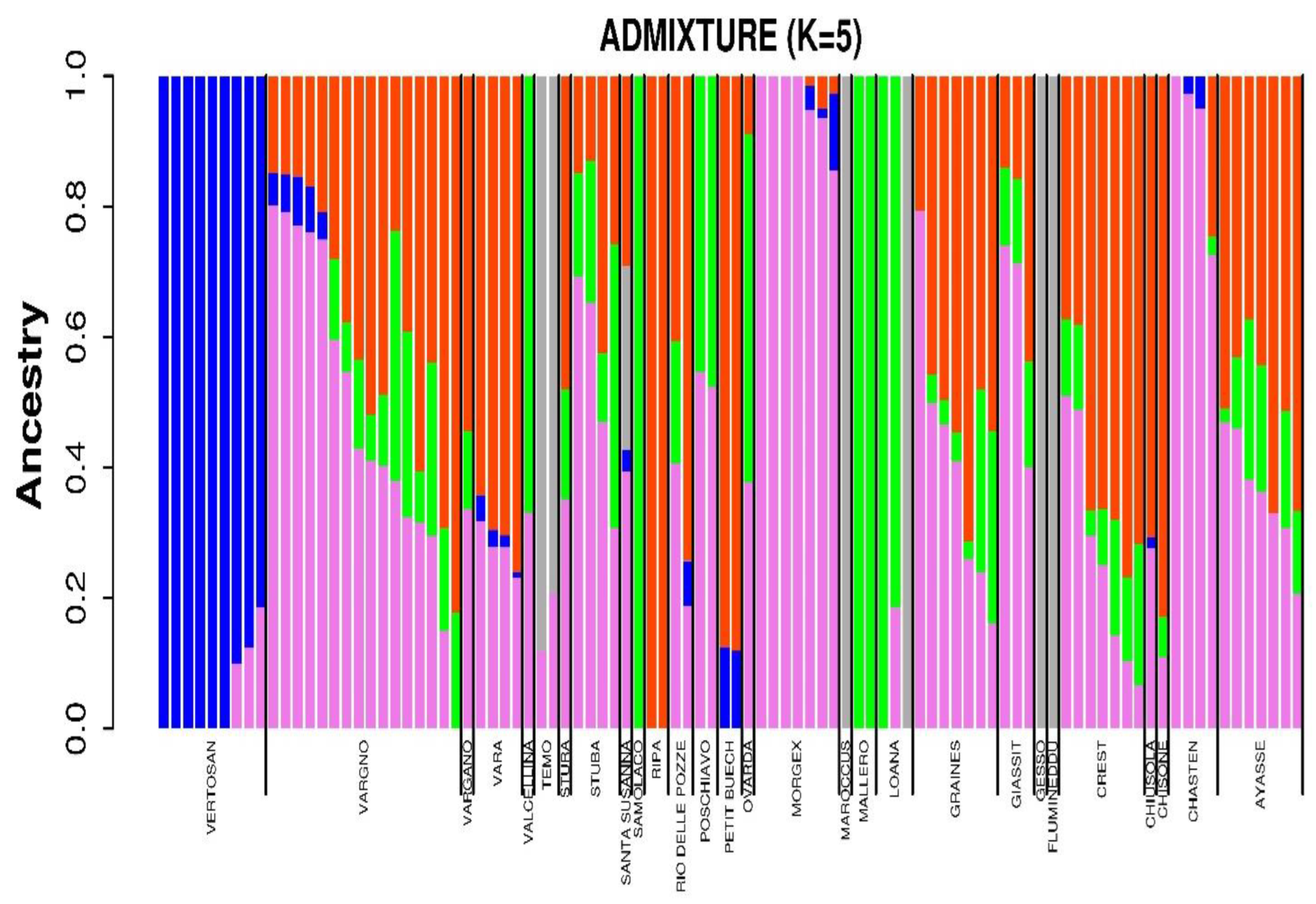

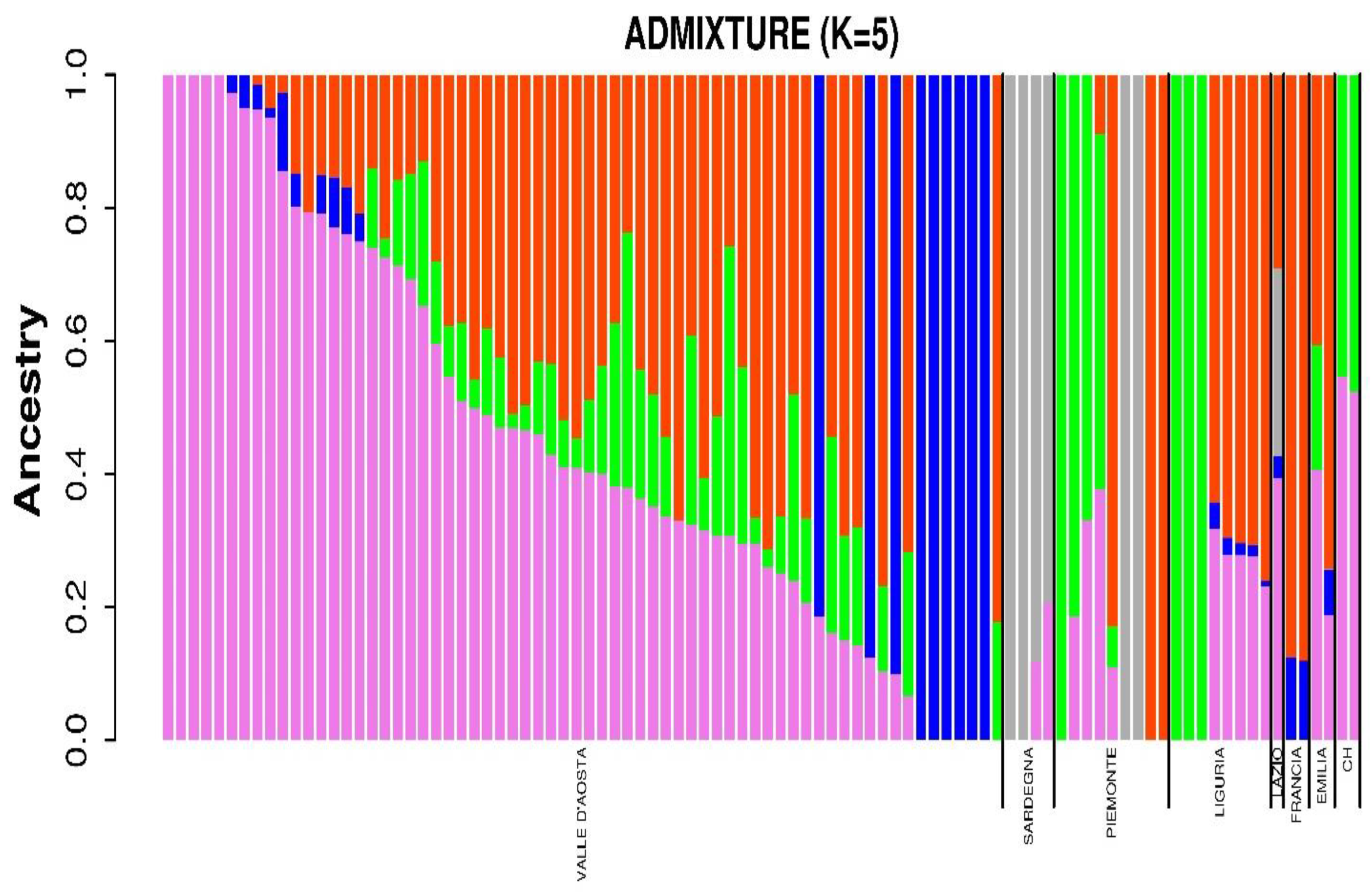

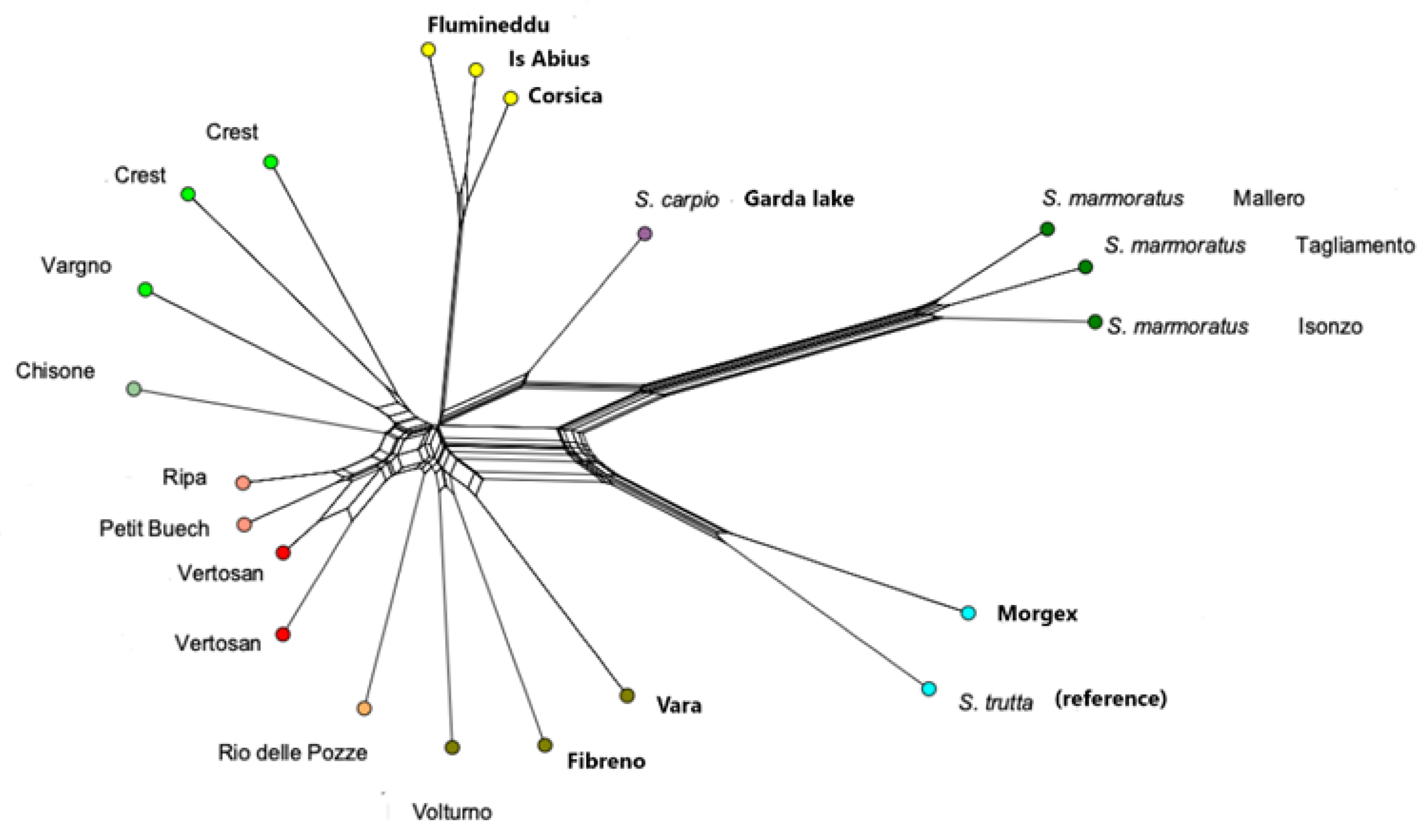

3.2. Population Structure

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Splendiani, A.; Fioravanti, T.; Giovannotti, M.; Olivieri, L.; Ruggeri, P.; Cerioni, P.N.; Vanni, S.; Enrichetti, F.; Barucchi, V.C. Museum samples could help to reconstruct the original distribution of Salmo trutta complex in Italy. J. Fish Biol. 2017, 90, 2443–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Splendiani, A.; Berrebi, P.; Tougard, C.; Righi, T.; Reynaud, N.; Fioravanti, T.; Lo Conte, P.; Delmastro, G.B.; Baltieri, M.; Ciuffardi, L.; et al. The role of the south-western Alps as a unidirectional corridor for Mediterranean brown trout (Salmo trutta complex) lineages. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2020, 131, 909–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antognazza, C. M.; Palandaćić, A.; Delmastro, G. B.; Crosa, G.; Zaccara, S. Current and Historical Genetic Variability of Native Brown Trout Populations in a Southern Alpine Ecosystem: Implications for Future Management. Fishes 2023, 8, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernatchez, L. The evolutionary history of brown trout (Salmo trutta L.) inferred from phylogeographic, nested clade, and mismatch analyses of mitochondrial DNA variation. Evolution 2001, 55, 351–379. [Google Scholar]

- Berrebi, P. Three brown trout Salmo trutta lineages in Corsica described through allozyme variation. J. Fish Biol. 2015, 86, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrebi, P.; Barucchi, V.C.; Splendiani, A.; Muracciole, S.; Sabatini, A.; Palmas, F.; Tougard, C.; Arculeo, M.; Maric, S. Brown trout (Salmo trutta L.) high genetic diversity around the Tyrrhenian Sea as revealed by nuclear and mitochondrial markers. Hydrobiologia 2019, 826, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrebi, P.; Horvath, Á.; Splendiani, A.; Palm, S.; Berna’s, R. Genetic diversity of domestic brown trout stocks in Europe. Aquaculture 2021, 544, 737043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffra, E.; Bernatchez, L.; Guyomard, R. Mitochondrial control region and protein coding genes sequence variation among phenotypic forms of brown trout Salmo trutta from northern Italy. Mol. Ecol. 1994, 3, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratton, P.; Allegrucci, G.; Sbordoni, V.; Gandolfi, A. The evolutionary jigsaw puzzle of the surviving trout (Salmo trutta L. complex) diversity in the Italian region. A multilocus Bayesian approach. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2014, 79, 292–304.

- Snoj, A.; Mari’c, S.; Bajec, S.S.; Berrebi, P.; Janjani, S.; Schöffmann, J. Phylogeographic structure and demographic patterns of brown trout in North-West Africa. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2011, 61, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffra, E.; Bernatchez, L.; Guyomard, R. Mitochondrial control region and protein coding genes sequence variation among phenotypic forms of brown trout Salmo trutta from northern Italy. Mol. Ecol. 1994, 3, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meraner, A.; Gandolfi, A. Genetics of the genus Salmo in Italy: Evolutionary history, population structure, molecular ecology and conservation. Brown trout: Biol. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 65–102. [Google Scholar]

- Polgar, G.; Iaia, M.; Righi, T.; Volta, P. The Italian Alpine and Subalpine trouts: taxonomy, evolution, and conservation. Biology 2022, 11, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Agaro, E.; Gibertoni, P.; Marroni, F.; Messina, M.; Tibaldi, E.; Esposito, S. Genetic and phenotypic characteristics of the Salmo trutta complex in Italy. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecaudey, L.A.; Schliewen, U.K.; Osinov, A.G.; Taylor, E.B.; Bernatchez, L.; Weiss, S.J. Inferring phylogenetic structure, hybridization and divergence times within Salmoninae (Teleostei: Salmonidae) using RAD-sequencing. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2018, 124, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemopoulos, A.; Prokkola, J.M.; Uusi-Heikkilä, S.; Vasemägi, A.; Huusko, A.; Hyvärinen, P.; Koljonen, M.; Koskiniemi, J.; Vainikka, A. Comparing RADseq and microsatellites for estimating genetic diversity and relatedness—Implications for brown trout conservation. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 2106–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magris, G.; Marroni, F.; D’Agaro, E.; Vischi, M.; Chiabà, C.; Scaglione, D.; Kijas, J.; Messina, M.; Tibaldi, E.; Morgante, M. ddRAD-seq reveals the genetic structure and detects signals of selection in Italian brown trout. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2022, 54, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA Sequence Polymorphism Analysis of Large Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMeel, O.M.; Hoey, E.M.; Ferguson, A. Partial nucleotide sequences, and routine typing by polymerase chain reactionrestriction fragment length polymorphism, of the brown trout (Salmo trutta) lactate dehydrogenase, LDH-C1*90 and *100 alleles. Mol. Ecol. 2001, 10, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochette, N. C.; Rivera-Colon, A.G.; Catchen, J.M. Stacks 2: Analytical methods for paired-end sequencing improve RADseq-based population genomics. Mol. Ecol. 2019, 28, 4737–4754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv, 2013; arXiv:arXiv:1303.3997v2. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, D.H.; Novembre, J.; Lange, K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 1655–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segherloo, I.H.; Freyhof, J.; Berrebi, P.; Ferchaud, A.L.; Geiger, M.; Laroche, J.; Levin, B.A.; Normandeau, E.; Bernatchez, L. A genomic perspective on an old question: Salmo trouts or Salmo trutta (Teleostei: Salmonidae)? Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2021, 162, 107204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, I.; Schuler, J.; Bezault, E.; Seehausen, O. Parallel divergent adaptation along replicated altitudinal gradients in Alpine trout. BMC Evol. Biol. 2012, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segherloo, I.H. , Freyhof, J.; Berrebi, P.; Ferchaud, A.L.; Geiger, M.; Laroche, J.; Bernatchez, L. A genomic perspective on an old question: Salmo trouts or Salmo trutta (Teleostei: Salmonidae)? Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2021, 162, 107204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| River catchment | Number of samples | Lon °(N) | Lat °(E) |

| Ayasse | 20 | 39°93′05.25” | 74°11′1.94 |

| Chasten | “ | 40°23′28.53” | 74°73′3.40 |

| Chisone | “ | 44°49′13.2” | 72°45′1.76 |

| Chiusola | “ | 44°17′37.44” | 94°03′1.54 |

| Crest | “ | 39°72′07.72” | 75°43′5.79 |

| Flumineddu | “ | 39°32′43.39” | 92°25′3.04 |

| Gesso | “ | 44°24′26.78” | 73°32′1.66 |

| Giassit | “ | 41°16′92.99” | 74°72′7.17 |

| Isonzo | “ | 46°24′42.56” | 134°32′6.79 |

| Loana | “ | |44°07′44.41” | 81°53′5.36 |

| Mallero | “ | 46°20′29.85” | 94°35′4.69 |

| Maroccu | “ | 39°13′04.65” | 84°91′5.45 |

| Morgex | “ | 34°85′80.76” | 70°24′5.45 |

| Ovarda | “ | 44°52′19.39” | 83°06′5.68 |

| Petit Buëch | “ | 44°11′51.28” | 55°63′5.16 |

| Poschiano | “ | 46°25′00.79” | 100°30′8.95 |

| Rio delle pozze | “ | 46°16′35.06” | 113°65′5.50 |

| Ripa | “ | 44°57′20.05” | 64°73′2.53 |

| Samolacco | “ | 46°16′46.16” | 92°34′6.23 |

| Santa susanna | “ | 42°30′09.82” | 125°19′6.56 |

| Stuba | “ | 40°47′70.10” | 77°34′3.39 |

| Stura | “ | 45°08′55.26” | 82°05′2.47 |

| Temo | “ | 40°17′26.57” | 82°83′3.47 |

| Toce | “ | 45°56′08.07” | 82°93′0.04 |

| Valcellina | “ | 46°10′00.30” | 124°00′0.21 |

| Vara | “ | 44°09′09.30” | 95°31′4.97 |

| Vargno 1 | “ | 41°08′94.27” | 75°44′0.97 |

| Vargno 2 | “ | 41°23′91.34” | 75°23′0.21 |

| Vertosan | “ | 35°42′22.44” | 71°54′0.29 |

| Volturno | “ | 41°38′14.60” | 140°41′6.81 |

| River catchment | Mt DNA-CRaplotypes | LDH-C1*alleles | ddRAD-seq Q (Ancestry to AT) |

| Morgex | AT | 90/90 | 0.96 |

| Ayasse | AD AT MA | 90/100 | 0.36 |

| Chasten | AT | 90/90 | 0.91 |

| Crest | AD AT MA | 90/100 | 0.25 |

| Giassit | AT AD | 90/100 | 0.61 |

| Graines | ME AT MA | 90/100 | 0.40 |

| Stuba | AT AD MA | 90/100 | 0.53 |

| Vargno | ME AT MA | 90/100 | 0.46 |

| Vertosan | ME | 100/100 | 0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).