Submitted:

13 May 2025

Posted:

14 May 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

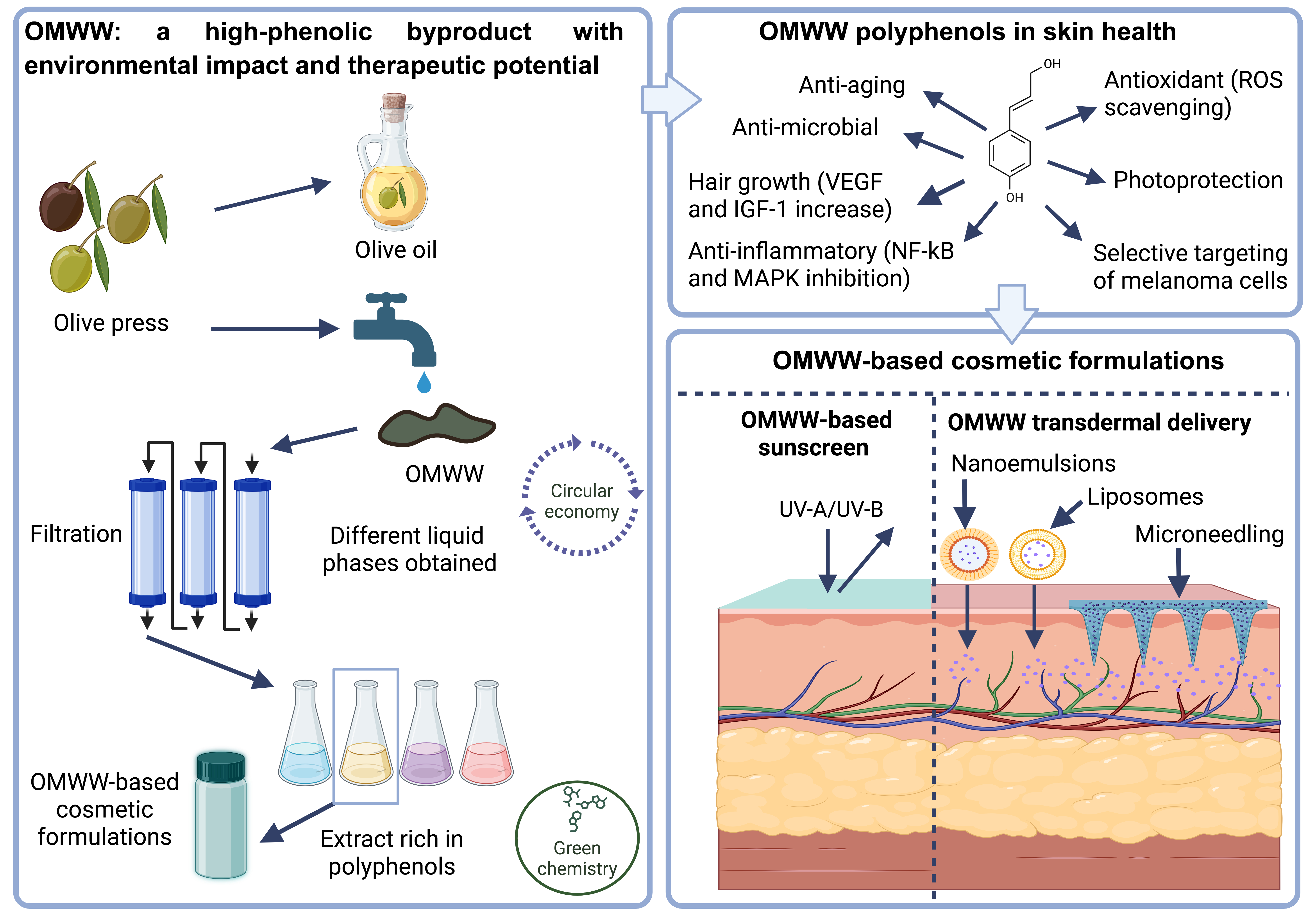

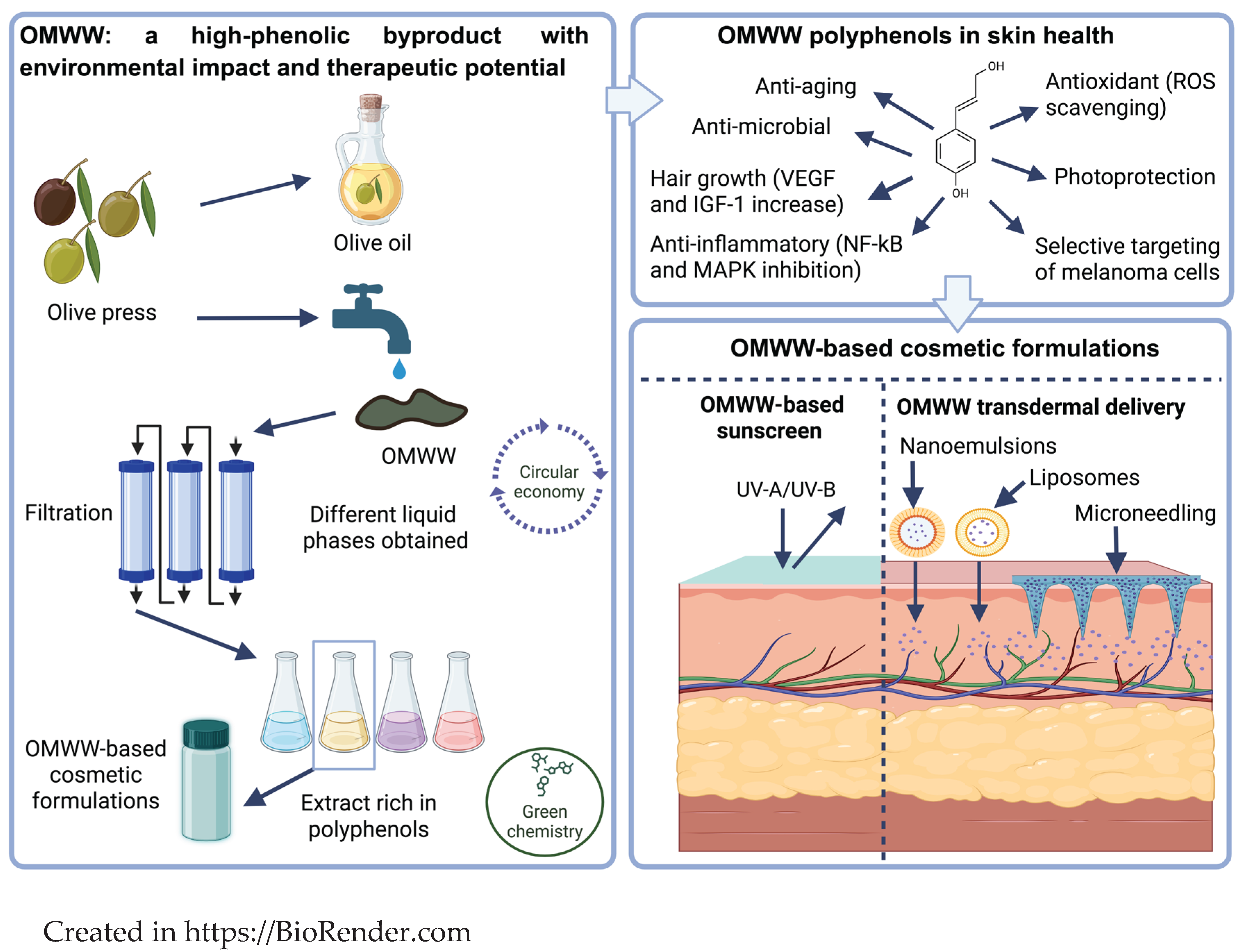

Skin health plays a vital role beyond aesthetics, contributing to essential physiological functions such as infection prevention (Kennedy et al., 2018), thermoregulation, water loss hindrance and ultraviolet (UV) radiation exposure protection (Ibrahim et al., 2021; Biniek et al., 2012). Structurally, the skin is composed of three main layers, epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue, each with distinct but complementary roles in maintaining homeostasis (Wickett et al., 2006; Yousef et al., 2025; Wong et al., 2016; Hirao, 2017). The outermost layer, the epidermis, is composed of keratinocytes, corneocytes, and melanocytes, which are responsible for retaining moisture, preventing pathogen entry, and shielding deeper layers from harmful environmental agents, UV light and burns. Beneath this lies the dermis, a layer enriched with blood vessels, nerves, sweat glands, and sebaceous glands that contribute to skin elasticity, hydration, and sensory reception. The deepest layer, the subcutaneous tissue, is composed of fat and connective tissue, providing insulation, energy storage, and mechanical cushioning (López-Ojeda et al., 2019). Within the epidermis, the stratum corneum serves as the skin’s primary barrier against external agents. It consists of interlocked corneocytes embedded in lipid bilayers, creating a robust defence against the penetration of harmful molecules (Hwa et al., 2011). The skin functions as a metabolic defence barrier that helps block UV radiation from reaching deeper tissues (Verma et al., 2024). However, prolonged exposure to solar UV radiation, particularly UV-A and UV-B, can lead to oxidative stress and skin damage. Notably, UV-B radiation is capable of penetrating the full thickness of the epidermis and reaching the dermis layer of human skin (Addas et al., 2021). Skin cancer, including melanoma and more common non-melanoma types such as basal and squamous cell carcinomas, represents a significant and growing public health burden, largely driven by UV radiation exposure, underscoring the critical importance of consistent and effective photoprotection (Raymond-Lezman et al., 2024; Rager et al., 2005; Ahmed et al., 2020). Besides skin cancer, several other skin and subcutaneous disorders, including acne, alopecia, bacterial and fungal infections, pressure ulcers, pruritus, psoriasis, scabies, urticaria, and viral skin conditions, contribute substantially to the global disease burden, affecting nearly one-third of the population and exerting both physical and psychological impacts (Urban et al., 2020; Flohr et al., 2021). The public health significance of skin conditions has been recognized globally. Most recently, the 77th World Health Assembly (May 29, 2024) emphasized the need to integrate dermatological care into universal health coverage systems due to the widespread and long-term consequences of untreated skin disorders. Environmental and lifestyle factors, including diet, hydration, sleep, and stress management, significantly influence skin health, emphasizing the need for a holistic approach (Saluja et al., 2017; Knaggs et al., 2023). Fundamental skincare practices, such as cleansing, moisturizing, and the daily use of sunscreen, are essential to preserve and improve skin functions (Lodén, 2012; Draelos, 2018). While the stratum corneum is essential for maintaining skin integrity, this protective mechanism presents a significant challenge for the delivery of active ingredients in skincare (López-Ojeda et al., 2019; Mărănducă et al., 2020). To address this, the cosmetic industry has developed innovative formulations and technologies, such as nanoemulsions, liposomes, and microneedling, which can selectively overcome the skin’s barrier function and enable the targeted delivery of active compounds to deeper skin layers (Pegoraro et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2020; Gorzelanny et al., 2020; Seah et al., 2018). Among these, oil-in-water (O/W) emulsions are particularly valued for their ability to solubilize and deliver natural compounds with antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activity that are otherwise poorly soluble (Ponphaiboon et al., 2024).

Skin health plays a vital role beyond aesthetics, contributing to essential physiological functions such as infection prevention (Kennedy et al., 2018), thermoregulation, water loss hindrance and ultraviolet (UV) radiation exposure protection (Ibrahim et al., 2021; Biniek et al., 2012). Structurally, the skin is composed of three main layers, epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue, each with distinct but complementary roles in maintaining homeostasis (Wickett et al., 2006; Yousef et al., 2025; Wong et al., 2016; Hirao, 2017). The outermost layer, the epidermis, is composed of keratinocytes, corneocytes, and melanocytes, which are responsible for retaining moisture, preventing pathogen entry, and shielding deeper layers from harmful environmental agents, UV light and burns. Beneath this lies the dermis, a layer enriched with blood vessels, nerves, sweat glands, and sebaceous glands that contribute to skin elasticity, hydration, and sensory reception. The deepest layer, the subcutaneous tissue, is composed of fat and connective tissue, providing insulation, energy storage, and mechanical cushioning (López-Ojeda et al., 2019). Within the epidermis, the stratum corneum serves as the skin’s primary barrier against external agents. It consists of interlocked corneocytes embedded in lipid bilayers, creating a robust defence against the penetration of harmful molecules (Hwa et al., 2011). The skin functions as a metabolic defence barrier that helps block UV radiation from reaching deeper tissues (Verma et al., 2024). However, prolonged exposure to solar UV radiation, particularly UV-A and UV-B, can lead to oxidative stress and skin damage. Notably, UV-B radiation is capable of penetrating the full thickness of the epidermis and reaching the dermis layer of human skin (Addas et al., 2021). Skin cancer, including melanoma and more common non-melanoma types such as basal and squamous cell carcinomas, represents a significant and growing public health burden, largely driven by UV radiation exposure, underscoring the critical importance of consistent and effective photoprotection (Raymond-Lezman et al., 2024; Rager et al., 2005; Ahmed et al., 2020). Besides skin cancer, several other skin and subcutaneous disorders, including acne, alopecia, bacterial and fungal infections, pressure ulcers, pruritus, psoriasis, scabies, urticaria, and viral skin conditions, contribute substantially to the global disease burden, affecting nearly one-third of the population and exerting both physical and psychological impacts (Urban et al., 2020; Flohr et al., 2021). The public health significance of skin conditions has been recognized globally. Most recently, the 77th World Health Assembly (May 29, 2024) emphasized the need to integrate dermatological care into universal health coverage systems due to the widespread and long-term consequences of untreated skin disorders. Environmental and lifestyle factors, including diet, hydration, sleep, and stress management, significantly influence skin health, emphasizing the need for a holistic approach (Saluja et al., 2017; Knaggs et al., 2023). Fundamental skincare practices, such as cleansing, moisturizing, and the daily use of sunscreen, are essential to preserve and improve skin functions (Lodén, 2012; Draelos, 2018). While the stratum corneum is essential for maintaining skin integrity, this protective mechanism presents a significant challenge for the delivery of active ingredients in skincare (López-Ojeda et al., 2019; Mărănducă et al., 2020). To address this, the cosmetic industry has developed innovative formulations and technologies, such as nanoemulsions, liposomes, and microneedling, which can selectively overcome the skin’s barrier function and enable the targeted delivery of active compounds to deeper skin layers (Pegoraro et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2020; Gorzelanny et al., 2020; Seah et al., 2018). Among these, oil-in-water (O/W) emulsions are particularly valued for their ability to solubilize and deliver natural compounds with antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activity that are otherwise poorly soluble (Ponphaiboon et al., 2024).2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Leveraging Phytocompounds in Cosmeceutical Formulations: Market Trends and Delivery Advances

- Penetration of Active Ingredients: The active compound must penetrate the stratum corneum in sufficient concentration to reach its target site within the skin.

- Known Mechanism of Action: The compound must have a clearly understood mechanism by which it achieves its effect, such as promoting collagen synthesis, inhibiting pigmentation, or reducing inflammation.

- Clinical efficacy: The product must demonstrate measurable results consistent with its claims through well-designed clinical trials.

3.2. Overview of Skin Care Products Delivery Technologies

3.3. Characterization of Olive Oil and Olive Oil Preparation Byproducts Composition: Applications in Dermatology

3.4. Anti-Aging, Photoprotective and Anti-Microbial Potential in Skin Applications

3.5. Anti-Inflammatory Effects and Pathway Modulation

3.6. Skin Cancer Prevention and Selective Antiproliferative Effects

3.7. Hair Health and Follicular Stimulation by OMWW

4. Conclusions

5. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data availability statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Abu-Lafi, S. Al-Natsheh, M.S., Yaghmoor, R. & Al-Rimawi, F. (2017) ’Enrichment of Phenolic Compounds from Olive Mill Wastewater and In Vitro Evaluation of Their Antimicrobial Activities’. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2017, 3706915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addas, A. Ragab, M., Maghrabi, A., Abo-Dahab, S.M. & El-Nobi, E.F. (2021) ’UV Index for Public Health Awareness Based on OMI/NASA Satellite Data at King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia’. Advances in Mathematical Physics 2021, 2835393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggoun, M. , Arhab, R., Cornu, A., Portelli, J. & Barkat, M. (2016) ’Olive mill wastewater: Phenolic composition and antioxidant activity’, Journal of Environmental Management, 170(1), pp. 1–9.

- Agramunt, J. , Parke, B., Mena, S., Ubels, V., Jimenez, F., Williams, G., Rhodes, A.D., Limbu, S., Hexter, M., Knight, L., Hashemi, P., Kozlov, A.S. & Higgins, C.A. (2023) ’Mechanical stimulation of human hair follicle outer root sheath cultures activates adjacent sensory neurons’, Science Advances, 9(43), eadh3273. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, B. , Qadir, M.I. & Ghafoor, S. (2020) ’Malignant Melanoma: Skin Cancer-Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment’, Critical Reviews in Eukaryotic Gene Expression, 30(4), pp. 291–297. [CrossRef]

- Aiello, A. , et al. (2024) ’Effect of a Phytochemical-Rich Olive-Derived Extract on Anthropometric, Hematological, and Metabolic Parameters’, Nutrients, 16(18), p. 3068. [CrossRef]

- Albanesi, C. , De Pità, O. & Girolomoni, G. (2005) ’Resident skin cells in psoriasis: a special look at the pathogenetic functions of keratinocytes’, Clinics in Dermatology, 25(6), pp. 581–588.

- Albini, A. , Albini, F., Corradino, P., Dugo, L., Calabrone, L. & Noonan, D.M. (2023) ’From antiquity to contemporary times: how olive oil by-products and wastewater can contribute to health’, Frontiers in Nutrition, 10. [CrossRef]

- Albini, A. et al. A Polyphenol-Rich Extract of Olive Mill Wastewater Enhances Cancer Chemotherapy Effects, While Mitigating Cardiac Toxicity. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12, 694762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albini, A. , et al. (2019) ’Nutraceuticals and ‘Repurposed’ Drugs of Phytochemical Origin in Prevention and Interception of Chronic Degenerative Diseases and Cancer’, Current Medicinal Chemistry, 26(6), pp. 973–987. [CrossRef]

- Alkhalidi, H. , Sciubba, F. & Gallo, G. (2023) ’Olive mill wastewater: From by-product to smart antioxidant material’, Sustainability, 15(5), p. 1234.

- Almohanna, H.M. , Ahmed, A.A., Tsatalis, J.P. & Tosti, A. (2019) ’The Role of Vitamins and Minerals in Hair Loss: A Review’, Dermatology and Therapy (Heidelberg), 9(1), pp. 51–70. [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-Soto, M. , Sánchez-Hidalgo, M., Rosillo, M.Á., Castejón, M.L. & Alarcón-de-la-Lastra, C. (2019) ’Extra virgin olive oil: a key functional food for prevention of immune-inflammatory diseases’, Food & Function, 10(7), pp. 3805–3824.

- Avola, R. , Graziano, A.C.E., Pannuzzo, G., Bonina, F. & Cardile, V. (2019) ’Hydroxytyrosol from olive fruits prevents blue-light-induced damage in human keratinocytes and fibroblasts’, Journal of Cellular Physiology, 234(6), pp. 9065–9076. [CrossRef]

- Baci, D. , et al. (2019) ’Downregulation of Pro-Inflammatory and Pro-Angiogenic Pathways in Prostate Cancer Cells by a Polyphenol-Rich Extract from Olive Mill Wastewater’, International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(2), p. 307. [CrossRef]

- Barone, M. , De Bernardis, R. & Persichetti, P. (2024) ’Aesthetic Medicine Across Generations: Evolving Trends and Influences’, Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. [CrossRef]

- Bassani, B. , et al. (2016) ’Potential Chemopreventive Activities of a Polyphenol Rich Purified Extract from Olive Mill Wastewater on Colon Cancer Cells’, Journal of Functional Foods, 27, pp. 236–248. [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, N. et al. (2022) ’An Olive Oil Mill Wastewater Extract Improves Chemotherapeutic Activity Against Breast Cancer Cells While Protecting From Cardiotoxicity. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2022, 9, 867867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benincasa, C. , Santoro, I., Nardi, M., Cassano, A. & Sindona, G. (2019) ’Eco-Friendly Extraction and Characterisation of Nutraceuticals from Olive Leaves’, Molecules, 24(19), p. 3481. [CrossRef]

- Biniek, K. , Levi, K. & Dauskardt, R.H. (2012) ’Solar UV radiation reduces the barrier function of human skin’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(42), pp. 17111–17116. [CrossRef]

- Bressel, M. , Kauffmann, J. & Schmitt, S. (2024) ’Critical Review of Techniques for Food Emulsion Characterization: Rheological Analysis of Emulsions and Their Implications for Formulation Stability’, Food Hydrocolloids, 102(3), pp. 1069–1085. [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, N. , Formisano, D. & Genovese, A. (2023) ’Valorization of lyophilized olive mill wastewater: Chemical and biological properties for functional applications’, Sustainability, 15(4), p. 3360.

- Cardinali, A. , De Marco, E. & De Santis, G. (2010) ’Phenolic compounds in olive mill wastewater: Analysis and characterization’, Food Chemistry, 120(3), pp. 690–695.

- Carrara, M. , Kelly, M.T., Roso, F., Larroque, M. & Margout, D. (2021) ’Potential of Olive Oil Mill Wastewater as a Source of Polyphenols for the Treatment of Skin Disorders: A Review’, Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 69(26), pp. 7268–7284. [CrossRef]

- Carrara, M. Beccali, M., Cellura, M. & Pipitone, F. (2021) ’Olive mill wastewater: A source of biologically active compounds. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 279, 123841. [Google Scholar]

- Chinembiri, T.N. , du Plessis, L.H., Gerber, M., Hamman, J.H. & du Plessis, J. (2014) ’Review of natural compounds for potential skin cancer treatment’, Molecules, 19(8), pp. 11679–11721.

- Cuffaro, D. , Vassallo, A. & La Carrubba, V. (2023) ’Valorization of olive mill wastewater: Recovery of bioactive compounds for food applications’, Sustainability, 15(1), p. 1234.

- Dauber, C. , Parente, E., Zucca, M.P., Gámbaro, A. & Vieitez, I. (2023) ’Olea europea and By-Products: Extraction Methods and Cosmetic Applications’, Cosmetics, 10(4), p. 112. [CrossRef]

- De Cicco, P. , Catani, M.V., Gasperi, V., Sibilano, M., Quaglietta, M. & Savini, I. (2022) ’Olive Leaf Extract Inhibits Proliferation, Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Metastatic Potential of Human Melanoma Cells’, Antioxidants, 11(2), p. 263.

- Di Mauro, M.D. , Tomasello, B., Giardina, R.C., Dattilo, S., Mazzei, V., Sinatra, F., Caruso, M., D’Antona, N. & Renis, M. (2017) ’Sugar and mineral enriched fraction from olive mill wastewater for promising cosmeceutical application: Characterization, in vitro and in vivo studies’, Food & Function, 8(12), pp. 4713–4722.

- Draelos, Z.D. (2018) ’The science behind skin care: Cleansers’, Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, 17(1), pp. 8–14. [CrossRef]

- El-Abbassi, A. , Fadhl, B.M. & Khaireddine, A. (2012) ’Olive mill wastewater: A review on its composition and treatment methods’, Journal of Environmental Management, 95(Suppl), pp. S1–S15.

- Flohr, C. & Hay, R. (2021) ’Putting the burden of skin diseases on the global map’, British Journal of Dermatology, 184(2), pp. 189–190. [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C. , Bonafè, M., Valensin, S., Olivieri, F., De Luca, M., Ottaviani, E. & De Benedictis, G. (2000) ’Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence’, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 908, pp. 244–254. [CrossRef]

- Fulop, T. , Larbi, A., Pawelec, G., Khalil, A., Cohen, A.A., Hirokawa, K., Witkowski, J.M. & Franceschi, C. (2023) ’Immunology of Aging: the Birth of Inflammaging’, Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology, 64(2), pp. 109–122. [CrossRef]

- Gallazzi, M. , et al. (2020) ’An Extract of Olive Mill Wastewater Downregulates Growth, Adhesion and Invasion Pathways in Lung Cancer Cells: Involvement of CXCR4′, Nutrients, 12(4), p. 903. [CrossRef]

- Galletti, F. , Peluso, G., Bifulco, M. & Russo, G.L. (2022) ’Biological effects of the olive tree and its derivatives on the skin’, Food & Function, 13(11), pp. 5952–5970.

- Ganesan, P. & Choi, D.K. (2016) ’Current application of phytocompound-based nanocosmeceuticals for beauty and skin therapy’, International Journal of Nanomedicine, 11, pp. 1987–2007. [CrossRef]

- Goldminz, A.M. , Au, S.C., Kim, N., Gottlieb, A.B. & Lizzul, P.F. (2013) ’NF-κB: An essential transcription factor in psoriasis’, Journal of Dermatological Science, 69(2), pp. 89–94.

- González-Acedo, A. , Ramos-Torrecillas, J., Illescas-Montes, R., Costela-Ruiz, V.J., Ruiz, C., Melguizo-Rodríguez, L. & García-Martínez, O. (2023) ’The Benefits of Olive Oil for Skin Health: Study on the Effect of Hydroxytyrosol, Tyrosol, and Oleocanthal on Human Fibroblasts’, Nutrients, 15(9), p. 2077. [CrossRef]

- Gorini, I. , Iorio, S., Ciliberti, R., Licata, M. & Armocida, G. (2019) ’Olive oil in pharmacological and cosmetic traditions’, Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, 18, pp. 1575–1579. [CrossRef]

- Gorzelanny, C. , Meß, C., Schneider, S.W., Huck, V. & Brandner, J.M. (2020) ’Skin Barriers in Dermal Drug Delivery: Which Barriers Have to Be Overcome and How Can We Measure Them?’, Pharmaceutics, 12(7), p. 684. [CrossRef]

- Halloy, J. , Bernard, B.A., Loussouarn, G., Goldbeter, A. (2002) ’The follicular automaton model: Effect of stochasticity and of synchronization of hair cycles’, Journal of Theoretical Biology, 214(3), pp. 469–479. [CrossRef]

- Hirao, T. (2017) ’Structure and Function of Skin From a Cosmetic Aspect’, in Elsevier eBooks (p. 673). Elsevier BV. [CrossRef]

- Hua, S. (2015) ’Lipid-based nano-delivery systems for skin delivery of drugs and bioactives’, Frontiers in Pharmacology, 6, pp. 1–15.

- Hwa, C. , Bauer, E.A. & Cohen, D.E. (2011) ’Skin biology’, Dermatologic Therapy, 24, pp. 464–470. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, K.J. , Price, K., Rando, T.L., Boylan, J. & Dyer, A.R. (2018) ’Ensuring healthy skin as part of wound prevention: An integrative review of health professionals’ actions’, Journal of Wound Care, 27(11), pp. 707–715. [CrossRef]

- Kilic, A. , Masur, C., Reich, H., Knie, U., Dähnhardt, D., Dähnhardt-Pfeiffer, S. & Abels, C. (2019) ’Skin acidification with a water-in-oil emulsion (pH 4) restores disrupted epidermal barrier and improves structure of lipid lamellae in the elderly’, Journal of Dermatology, 46(6), pp. 457–465. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B. , Cho, H.-E., Moon, S.H., Ahn, H., Bae, S., Cho, H.-D. & An, S. (2020) ’Transdermal delivery systems in cosmetics’, in Biomedical Dermatology (Vol. 4, Issue 1). BioMed Central. [CrossRef]

- Kische, H. , Arnold, A., Gross, S., Wallaschofski, H., Völzke, H., Nauck, M. & Haring, R. (2017) ’Sex Hormones and Hair Loss in Men From the General Population of Northeastern Germany’, JAMA Dermatology, 153(9), pp. 935–937. [CrossRef]

- Kligman, D. (2000) ’Cosmeceuticals’, Dermatologic Clinics, 18(4), pp. 609–615. [CrossRef]

- Knaggs, H. & Lephart, E.D. (2023) ’Enhancing Skin Anti-Aging through Healthy Lifestyle Factors’, Cosmetics, 10(5), p. 142. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.A.E. , Bagherani, N., Smoller, B.R., Reyes-Baron, C. & Bagherani, N. (2021) ’Functions of the Skin’, in Atlas of Dermatology, Dermatopathology and Venereology. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Janakat, S. , Al-Nabulsi, A., Allehdan, S., Olaimat, A. & Holley, R. (2015) ’Antimicrobial activity of amurca (olive oil lees) extract against selected foodborne pathogens’, Food Science and Technology, 35, pp. 259–265. [CrossRef]

- Lasisi, T. , Smallcombe, J.W., Kenney, W.L., Shriver, M.D., Zydney, B., Jablonski, N.G. & Havenith, G. (2023) ’Human scalp hair as a thermoregulatory adaptation’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 120(24), e2301760120. [CrossRef]

- Lecci, R. , Romani, A., Ieri, F., Mulinacci, N., Pinelli, P., Bernini, R. & Caporali, A. (2021) ’Antioxidant and Pro-Oxidant Capacities as Mechanisms of Photoprotection of Olive Polyphenols on UVA-Damaged Human Keratinocytes’, Antioxidants, 10(4), p. 600.

- Li, H. , He, H., Liu, C., Akanji, T., Gutkowski, J., Li, R., Ma, H., Wan, Y., Wu, P., Li, D., Seeram, N.P. & Ma, H. (2022) ’Dietary polyphenol oleuropein and its metabolite hydroxytyrosol are moderate skin permeable elastase and collagenase inhibitors with synergistic cellular antioxidant effects in human skin fibroblasts’, International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 73(4), pp. 460–470. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X. Zhu, L. & He, J. (2022) ’Morphogenesis, Growth Cycle and Molecular Regulation of Hair Follicles. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2022, 10, 899095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litchman, G. , Nair, P.A., Badri, T. & Kelly, S.E. (2022) ’Microneedling’, in StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470464/.

- Lodén, M. (2012) ’Effect of moisturizers on epidermal barrier function’, Clinical Dermatology, 30(3), pp. 286–296. [CrossRef]

- López-Ojeda, W. , Pandey, A., Alhajj, M. & Oakley, A. (2019) ’Anatomy, Skin (Integument)’, in StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28723009.

- Mărănducă, A. , Mărănducă, L. & Simionescu, R. (2020) ’The structure and function of the skin’, Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology, 61(1), pp. 7–14.

- Masaki, H. (2010) ’Role of antioxidants in the skin: Anti-aging effects’, Journal of Dermatological Science, 58(2), pp. 85–90. [CrossRef]

- Mijatović, S. , Timotijević, G., Miljković, Đ., Radović, J., Maksimović-Ivanić, D., Dekanski, D. & Stošić-Grujičić, S. (2011) ’Multiple antimelanoma potential of dry olive leaf extract’, International Journal of Cancer, 128(8), pp. 1955–1965.

- Morávková, T. Stern, P. (2011) ’Rheological and Textural Properties of Cosmetic Emulsions. Applied Rheology 2011, 21, 35200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarelli, N. , Gahoonia, N. & Sivamani, R.K. (2023) ’Integrative and Mechanistic Approach to the Hair Growth Cycle and Hair Loss’, Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(3), p. 893. [CrossRef]

- Nomikos, N.N. , Nomikos, G.N. & Kores, D.S. (2010) ’The use of deep friction massage with olive oil as a means of prevention and treatment of sports injuries in ancient times’, Archives of Medical Science, 6(5), pp. 642–645. [CrossRef]

- Osmond, G.W. , Augustine, C.K., Zipfel, P.A., Padussis, J. & Tyler, D.S. (2012) ’Enhancing melanoma treatment with resveratrol’, Journal of Surgical Research, 172(1), pp. 109–115.

- Otto, A. , Du Plessis, J. & Wiechers, J.W. (2009) ’Formulation effects of topical emulsions on transdermal and dermal delivery’, International Journal of Cosmetic Science, 31(1), pp. 1–19.

- Pandey, A. , Jatana, G.K. & Sonthalia, S. (2023) ’Cosmeceuticals’, in StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan.

- Papadopoulou, A. , Petrotos, K., Stagos, D., Gerasopoulos, K., Maimaris, A., Makris, H., Kafantaris, I., Makri, S., Kerasioti, E., Halabalaki, M., Brieudes, V., Ntasi, G., Kokkas, S., Tzimas, P., Goulas, P., Zakharenko, A.M., Golokhvast, K.S., Tsatsakis, A. & Kouretas, D. (2017) ’Enhancement of Antioxidant Mechanisms and Reduction of Oxidative Stress in Chickens after the Administration of Drinking Water Enriched with Polyphenolic Powder from Olive Mill Waste Waters’, Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2017, p. 8273160. [CrossRef]

- Patel, M. & Joshi, A. (2012) ’Nanoemulsions for cosmeceutical applications: Advantages and formulation considerations’, Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 64(6), pp. 670–685.

- Pegoraro, C. , MacNeil, S. & Battaglia, G. (2012) ’Transdermal drug delivery: from micro to nano’, Nanoscale, 4(6), p. 1881. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pérez, V. , Jiménez-Martínez, C., González-Escobar, J.L. & Corzo-Ríos, L.J. (2024) ’Exploring the impact of encapsulation on the stability and bioactivity of peptides extracted from botanical sources: trends and opportunities’, Frontiers in Chemistry, 12, p. 1423500. [CrossRef]

- Perugini, P. , Vettor, M., Rona, C., Troisi, L., Villanova, L., Genta, I., Conti, B. & Pavanetto, F. (2008) ’Efficacy of oleuropein against UVB irradiation: preliminary evaluation’, International Journal of Cosmetic Science, 30(2), pp. 113–120. [CrossRef]

- Phelps, A.H. Jr. (1967) ’Air pollution aspects of soap and detergent manufacture’, Journal of the Air Pollution Control Association, 17(8), pp. 505–507. [CrossRef]

- Pojero, F. , Poma, P., Spanò, V., Montalbano, A., Barraja, P. & Notarbartolo, M. (2022) ’Targeting senescence with olive oil polyphenols as a novel therapeutic strategy for chronic diseases’, European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 227, p. 113910.

- Ponphaiboon, J. , Limmatvapirat, S. & Limmatvapirat, C. (2024) ’Development and Evaluation of a Stable Oil-in-Water Emulsion with High Ostrich Oil Concentration for Skincare Applications’, Molecules, 29(5), p. 982. [CrossRef]

- Rager, E.L. , Bridgeford, E.P. & Ollila, D.W. (2005) ’Cutaneous melanoma: update on prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment’, American Family Physician, 72(2), pp. 269–276.

- Raymond-Lezman, J.R. Riskin, S.I. (2024) ’Sunscreen Safety and Efficacy for the Prevention of Cutaneous Neoplasm. Cureus 2024, 16, e56369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivers, J.K. (2008) ’The role of cosmeceuticals in antiaging therapy’, Skin Therapy Letter, 13(8), pp. 5–9.

- Ruzzolini, J. , Peppicelli, S., Andreucci, E., Bianchini, F., Scardigli, A., Romani, A., la Marca, G., Nediani, C. & Calorini, L. (2018) ’Oleuropein, the Main Polyphenol of Olea europaea Leaf Extract, Has an Anti-Cancer Effect on Human BRAF Melanoma Cells and Potentiates the Cytotoxicity of Current Chemotherapies’, Nutrients, 10(12), p. 1950. [CrossRef]

- Saluja, S.S. & Fabi, S.G. (2017) ’A Holistic Approach to Antiaging as an Adjunct to Antiaging Procedures: A Review of the Literature’, Dermatologic Surgery, 43(4), pp. 475–484. [CrossRef]

- Sambhakar, P. , Malik, S., Bhatia, R., Al Harrasi, S., Rani, A., Saharan, R.C., Kumar, R., Suresh, G. & Sehrawat, R. (2023) ’Nanoemulsion: An Emerging Novel Technology for Improving the Bioavailability of Drugs’, Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 112(1), pp. 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Samra, T. , Lin, R.R. & Maderal, A.D. (2024) ’The Effects of Environmental Pollutants and Exposures on Hair Follicle Pathophysiology’, Skin Appendage Disorders, 10(4), pp. 262–272. [CrossRef]

- Schlupp, P. , Schmidts, T.M., Pössl, A., Wildenhain, S., Lo Franco, G., Lo Franco, A. & Lo Franco, B. (2019) ’Effects of a Phenol-Enriched Purified Extract from Olive Mill Wastewater on Skin Cells’, Cosmetics, 6(2), p. 30. [CrossRef]

- Sciubba, F. , Chronopoulou, L., Pizzichini, D., Lionetti, V., Fontana, C., Aromolo, R., Socciarelli, S., Gambelli, L., Bartolacci, B., Finotti, E., Benedetti, A., Miccheli, A., Neri, U., Palocci, C. & Bellincampi, D. (2020) ’Olive Mill Wastes: A Source of Bioactive Molecules for Plant Growth and Protection against Pathogens’, Biology (Basel), 9(12), p. 450. [CrossRef]

- Seah, B.C.-Q. & Teo, B.M. (2018) ’Recent advances in ultrasound-based transdermal drug delivery’, International Journal of Nanomedicine, 7749. Dove Medical Press. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N. & Sarangdevot, K. (2012) ’Nanoemulsions: A new topical drug delivery system for the treatment of acne’, Journal of Research in Pharmacy, 27(1), pp. 1–11.

- Sittek, L.-M. , Schmidts, T.M. & Schlupp, P. (2021) ’Polyphenol-Rich Olive Mill Wastewater Extract and Its Potential Use in Hair Care Products’, Journal of Cosmetics, Dermatological Sciences and Applications, 11, pp. 356–370.

- Smeriglio, A. , Denaro, M., Mastracci, L., Grillo, F., Cornara, L., Shirooie, S., Nabavi, S.M. & Trombetta, D. (2019) ’Safety and efficacy of hydroxytyrosol-based formulation on skin inflammation: in vitro evaluation on reconstructed human epidermis model’, DARU Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 27, pp. 283–293.

- Sofi, F. Cesari, F., Abbate, R., Gensini, G.F. & Casini, A. (2008) ’Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: meta-analysis. BMJ 2008, 337, a1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svobodová, A. , Psotová, J. & Walterová, D. (2003) ’Natural phenolics in the prevention of UV-induced skin damage: A review’, Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 147(2), pp. 137–145.

- Urban, K. , Chu, S., Giesey, R.L., Mehrmal, S., Uppal, P., Delost, M.E. & Delost, G.R. (2020) ’Burden of skin disease and associated socioeconomic status in Asia: A cross-sectional analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2017′, JAAD International, 2, pp. 40–50. [CrossRef]

- Urysiak-Czubatka, I. , Kmieć, M.L. & Broniarczyk-Dyła, G. (2014) ’Assessment of the usefulness of dihydrotestosterone in the diagnostics of patients with androgenetic alopecia’, Postępy Dermatologii i Alergologii, 31(4), pp. 207–215. [CrossRef]

- Verma, A. , Zanoletti, A., Kareem, K.Y. et al. (2024) ’Skin protection from solar ultraviolet radiation using natural compounds: a review’, Environmental Chemistry Letters, 22, pp. 273–295. [CrossRef]

- Visioli, F. , Galli, C. & Caruso, D. (1999) ’Antioxidant properties of olive oil phenols’, Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 10(5), pp. 305–310.

- Wang, H. , Syrovets, T., Kess, D., Büchele, B., Hainzl, H., Lunov, O. & Simmet, T. (2009) ’Targeting NF-κB with a natural triterpenoid alleviates skin inflammation in a mouse model of psoriasis’, Journal of Immunology, 183(7), pp. 4755–4763.

- Wickett, R.R. & Visscher, M.O. (2006) ’Structure and function of the epidermal barrier’, American Journal of Infection Control, 34(10). [CrossRef]

- Wong, R. , Geyer, S., Weninger, W., Guimberteau, J.-C. & Wong, J.K. (2016) ’The dynamic anatomy and patterning of skin’, Experimental Dermatology, 25, pp. 92–98. [CrossRef]

- World Health Assembly (WHA) (n.d.) ’Resolution on Skin Diseases’. Available at: https://globalskin.org/component/content/article/101-advocacy/641-wha-resolution-on-skin-diseases?Itemid=1710 (Accessed: [Insert Access Date]).

- Yousef, H. , Alhajj, M., Fakoya, A.O., et al. (2024) ’Anatomy, Skin (Integument), Epidermis’, in StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470464/.

- Zhang, H.L. , Qiu, X.X. & Liao, X.H. (2024) ’Dermal Papilla Cells: From Basic Research to Translational Applications’, Biology (Basel), 13(10), p. 842. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. , Harada, N. & Okajima, K. (2011) ’Dihydrotestosterone inhibits hair growth in mice by inhibiting insulin-like growth factor-I production in dermal papillae’, Growth Hormone & IGF Research, 21(5), pp. 260–267. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q. , Mrowietz, U. & Rostami-Yazdi, M. (2009) ’Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of psoriasis’, Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 47(7), pp. 891–905.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).