Submitted:

10 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

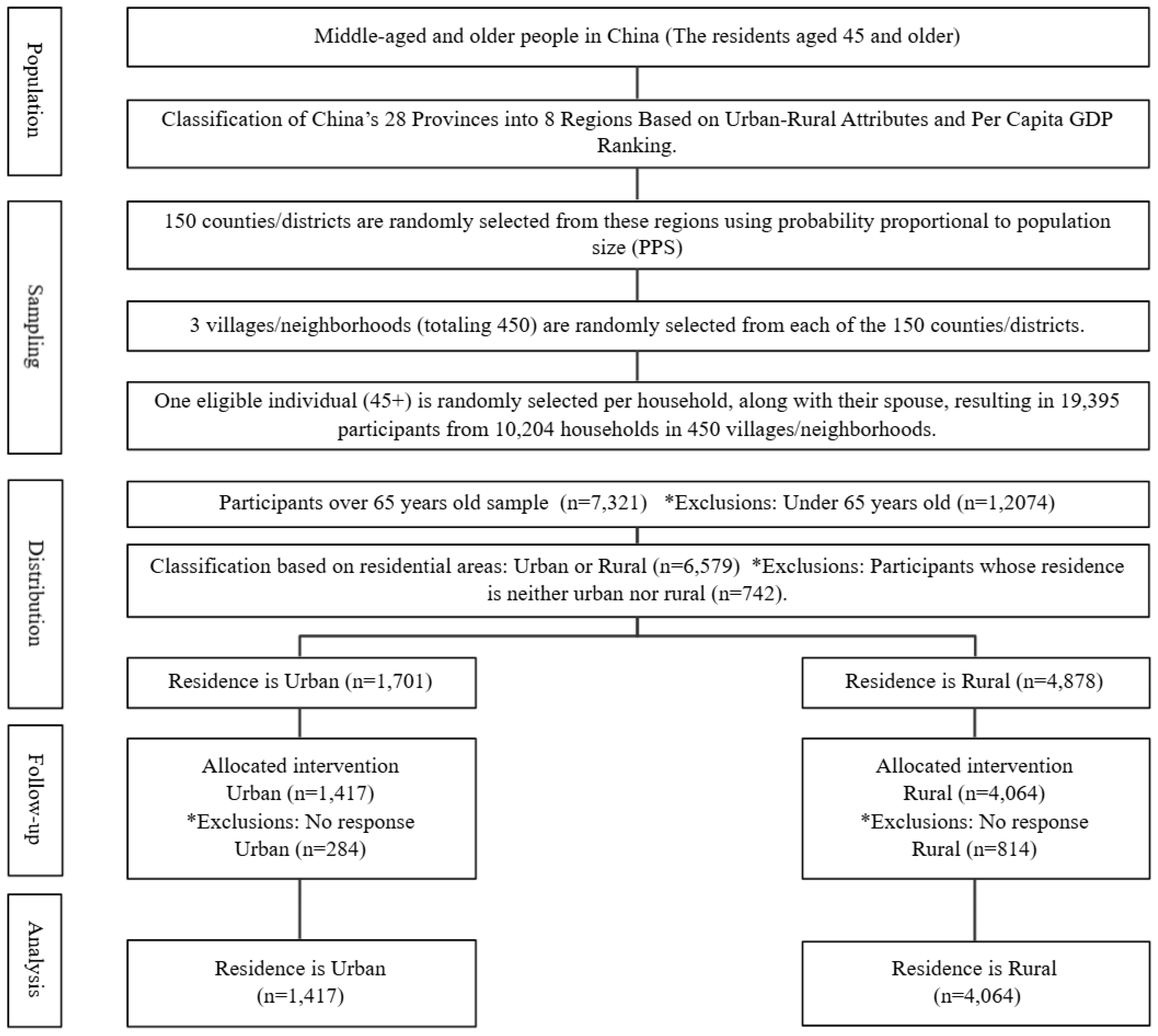

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Differences in Chronic Diseases by Residential Areas

3.1.1. Differences in Hypertension by Residential Areas

3.1.2. Differences in Diabetes by Residential Areas

3.1.3. Differences in Heart Disease by Residential Areas

3.1.4. Differences in Stroke by Residential Areas

3.2. Differences in Depression by Residential Areas

3.3. Correlation Between Urban Residence, PA, Chronic Diseases, and Depression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Implications

Declaration of Competing Interest

Data Availability

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. (2022, December 21). Notice on the issuance of the "Health China Action (2019-2030)" outline. State Council of the People's Republic of China. https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2022/content_5692863.htm.

- Hill, N. L. , Bhargava, S., Brown, M. J., Kim, H., Bhang, I., Mullin, K.,... & Mogle, J. Cognitive complaints in age-related chronic conditions: A systematic review. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0253795. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, Z., Zhang, Z., Ren, Y., Wang, Y., Fang, J., Yue, H., ... & Guan, F. (2021). Aging and age-related diseases: from mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Biogerontology, 22(2), 165-187.

- Sharma, P., Maurya, P., & Muhammad, T. (2021). Number of chronic conditions and associated functional limitations among older adults: cross-sectional findings from the longitudinal aging study in India. BMC Geriatrics, 21, 1-12.

- Abdoli, N., Salari, N., Darvishi, N., Jafarpour, S., Solaymani, M., Mohammadi, M., & Shohaimi, S. (2022). The global prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD) among the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 132, 1067-1073.

- Zhang, P., Wang, L., Zhou, Q., Dong, X., Guo, Y., Wang, P., ... & Sun, C. (2023). A network analysis of anxiety and depression symptoms in Chinese disabled elderly. Journal of Affective Disorders, 333, 535-542.

- Hu, D., Yan, W., Zhu, J., Zhu, Y., & Chen, J. (2021). Age-related disease burden in China, 1997-2017: findings from the global burden of disease study. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 638704.

- Lobanov-Rostovsky, S., He, Q., Chen, Y., Liu, Y., Wu, Y., Liu, Y., ... & Brunner, E. J. (2023). Growing old in China in socioeconomic and epidemiological context: systematic review of social care policy for older people. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 1272.

- Keramat, S. A., Alam, K., Rana, R. H., Chowdhury, R., Farjana, F., Hashmi, R., ... & Biddle, S. J. (2021). Obesity and the risk of developing chronic diseases in middle-aged and older adults: Findings from an Australian longitudinal population survey, 2009–2017. PLoS One, 16(11), e0260158.

- Delpino, F. M., de Lima, A. P. M., da Silva, B. G. C., Nunes, B. P., Caputo, E. L., & Bielemann, R. M. (2022). Physical activity and multimorbidity among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review with meta-analysis. American Journal of Health Promotion, 36(8), 1371-1385.

- Wong, M. Y. C., Ou, K. L., Chung, P. K., Chui, K. Y. K., & Zhang, C. Q. (2023). The relationship between physical activity, physical health, and mental health among older Chinese adults: A scoping review. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 914548.

- De Sousa, R. A. L., Rocha-Dias, I., de Oliveira, L. R. S., Improta-Caria, A. C., Monteiro-Junior, R. S., & Cassilhas, R. C. (2021). Molecular mechanisms of physical exercise on depression in the elderly: a systematic review. Molecular Biology Reports, 48, 3853-3862.

- Sardeli, A. V., Griffth, G. J., Dos Santos, M. V. M. A., Ito, M. S. R., & Chacon-Mikahil, M. P. T. (2021). The effects of exercise training on hypertensive older adults: an umbrella meta-analysis. Hypertension Research, 44(11), 1434-1443.

- Van Milligen, B. A., Lamers, F., de Hoop, G. T., Smit, J. H., & Penninx, B. W. (2011). Objective physical functioning in patients with depressive and/or anxiety disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 131(1-3), 193-199.

- Sosa, A. L., Miranda, B., & Acosta, I. (2021). Links between mental health and physical health, their impact on the quality of life of the elderly, and challenges for public health. In Understanding the Context of Cognitive Aging: Mexico and the United States pp. 63-87). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., & Glaser, R. (2002). Depression and immune function: central pathways to morbidity and mortality. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53(4), 873-876.

- Hossain, M. N., Lee, J., Choi, H., Kwak, Y. S., & Kim, J. (2024). The impact of exercise on depression: how moving makes your brain and body feel better. Physical Activity and Nutrition, 28(2), 43-51. https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2022/content_5692863.htm.

- Son, J. S., Nimrod, G., West, S. T., Janke, M. C., Liechty, T., & Naar, J. J. (2021). Promoting older adults’ physical activity and social well-being during COVID-19. Leisure Sciences, 43(1-2), 287-294.

- Xu, J., & Ma, J. (2024). Urban-Rural Disparity in the Relationship Between Geographic Environment and the Health of the Elderly. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy, 17(3), 1335-1357.

- Kappus, R. M. (2024). Addressing Physical Inactivity in Aging, Rural Communities. Journal of Clinical Exercise Physiology, 13(1), 18-21.

- Lin, S. F., Chu, C. H., Chou, W. T., Hsieh, T. C., & Kuo, Y. L. (2024). Different impacts of physical activity on health in urban and rural older adults. Public Health Nursing, 41(6), 1514-1525.

- Zhang, L., Sun, F., Li, Y., Tang, Z., & Ma, L. (2021). Multimorbidity in community-dwelling older adults in Beijing: prevalence and trends, 2004–2017. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 25, 116-119.

- Zhang, J., Xiao, S., Shi, L., Xue, Y., Zheng, X., Dong, F., ... & Zhang, C. (2022). Differences in health-related quality of life and its associated factors among older adults in urban and rural areas. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 15, 1447-1457.

- Fan, Z. Y., Yang, Y., Zhang, C. H., Yin, R. Y., Tang, L., & Zhang, F. (2021). Prevalence and patterns of comorbidity among middle-aged and elderly people in China: a cross-sectional study based on CHARLS data. International Journal of General Medicine, 1449-1455.

- Roomaney, R. A., van Wyk, B., Turawa, E. B., & Pillay-van Wyk, V. (2021). Multimorbidity in South Africa: a systematic review of prevalence studies. BMJ Open, 11(10), e048676.

- Zhou, X., & Zhang, D. (2021). Multimorbidity in the elderly: a systematic bibliometric analysis of research output. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 353.

- Chen, Y., Shi, L., Zheng, X., Yang, J., Xue, Y., Xiao, S., ... & Zhang, C. (2022). Patterns and determinants of multimorbidity in older adults: study in health-ecological perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16756.

- Lo, Y. P., Chiang, S. L., Lin, C. H., Liu, H. C., & Chiang, L. C. (2021). Effects of individualized aerobic exercise training on physical activity and health-related physical fitness among middle-aged and older adults with multimorbidity: a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), 101.

- Jørgensen, L. B., Bricca, A., Bernhardt, A., Juhl, C. B., Tang, L. H., Mortensen, S. R., ... & Skou, S. T. (2022). Objectively measured physical activity levels and adherence to physical activity guidelines in people with multimorbidity—A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 17(10), e0274846.

- Lee, J., Kim, J., Chow, A., & Piatt, J. A. (2021). Different levels of physical activity, physical health, happiness, and depression among older adults with diabetes. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 7, 2333721421995623.

- Lee, J. M., & Ryan, E. J. (2022). The relationship between the frequency and duration of physical activity and depression in older adults with multiple chronic diseases. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(21), 6355.

- Deng, Y., & Paul, D. R. (2018). The relationships between depressive symptoms, functional health status, physical activity, and the availability of recreational facilities: a rural-urban comparison in middle-aged and older Chinese adults. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 25, 322-330.

- Wang, Y., Li, Z., & Fu, C. (2021). Urban-rural differences in the association between social activities and depressive symptoms among older adults in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics, 21, 569.

- Li, Y., Cui, M., Pang, Y., Zhan, B., Li, X., Wang, Q., ... & Yang, Q. (2024). Association of physical activity with socio-economic status and chronic disease in older adults in China: cross-sectional findings from the survey of CLASS 2020 after the outbreak of COVID-19. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 37.

- Moreno-Llamas, A., García-Mayor, J., & De la Cruz-Sánchez, E. (2023). Urban–rural differences in perceived environmental opportunities for physical activity: a 2002–2017 time-trend analysis in Europe. Health Promotion International, 38(4), daad087.

- Muhammad, T., Srivastava, S., Hossain, B., Paul, R., & Sekher, T. V. (2022). Decomposing rural–urban differences in successful aging among older Indian adults. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 6430.

- Zhao, Y., Strauss, J., Chen, X., Wang, Y., Gong, J., Meng, Q., Wang, G., & Wang, H. (2020). China health and retirement longitudinal study wave 4 user’s guide. National School of Development, Peking University, pp. 5-6.

- Zhao, Y., Hu, Y., Smith, J. P., Strauss, J., & Yang, G. (2014). Cohort profile: the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(1), 61-68.

- Forde, C. (2018). Scoring the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). University of Dublin, p. 3.

- Boey, K. W. (1999). Cross-validation of a short form of the CES-D in Chinese elderly. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14(8), 608-617.

- Chen, H., & Mui, A. C. (2014). Factorial validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale short form in older population in China. International Psychogeriatrics, 26(1), 49-57.

- Fu, H., Si, L., & Guo, R. (2022). What is the optimal cut-off point of the 10-item center for epidemiologic Studies depression scale for screening depression among Chinese individuals aged 45 and over? An exploration using latent profile analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 820777.

- Guo, J., Guan, L., Fang, L., Liu, C., Fu, M., He, H., & Wang, X. (2017). Depression among Chinese older adults: A perspective from Hukou and health inequities. Journal of Affective Disorders, 223, 115-120.

- Tan, K. H. L. , & Siah, C. J. R. Effects of low-to-moderate physical activities on older adults with chronic diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2022, 31, 2072–2086. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Franklin, B. A., Eijsvogels, T. M., Pandey, A., Quindry, J., & Toth, P. P. (2022). Physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and cardiovascular health: A clinical practice statement of the ASPC Part I: Bioenergetics, contemporary physical activity recommendations, benefits, risks, extreme exercise regimens, potential maladaptations. American Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 12, 100424.

- You, Y., Teng, W., Wang, J., Ma, G., Ma, A., Wang, J., & Liu, P. (2018). Hypertension and physical activity in middle-aged and older adults in China. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 16098.

- Huang, Y., & Lu, Z. (2024). A cross-sectional study of physical activity and chronic diseases among middle-aged and elderly in China. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 30701.

- Lee, C. D., Folsom, A. R., & Blair, S. N. (2003). Physical activity and stroke risk: a meta-analysis. Stroke, 34(10), 2475-2481.

- Sanders, L. M. J., Hortobágyi, T., Karssemeijer, E. G. A., Van der Zee, E. A., Scherder, E. J. A., & Van Heuvelen, M. J. G. (2020). Effects of low-and high-intensity physical exercise on physical and cognitive function in older persons with dementia: a randomized controlled trial. Alzheimer's Research & Therapy, 12, 28.

- Li, M. A. (2018). Effect of physical activity on the metabolic diseases among elderly people in urban China-Based on the PASE of epidemiology. Journal of Shanghai University of Sport, 42(4), 100-104.

- Kanaley, J. A., Colberg, S. R., Corcoran, M. H., Malin, S. K., Rodriguez, N. R., Crespo, C. J., ... & Zierath, J. R. (2022). Exercise/physical activity in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a consensus statement from the American College of Sports Medicine. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 54(2), 353.

- Booth, F. W., Roberts, C. K., Thyfault, J. P., Ruegsegger, G. N., & Toedebusch, R. G. (2017). Role of inactivity in chronic diseases: evolutionary insight and pathophysiological mechanisms. Physiological Reviews.

- Kramer, A. (2020). An overview of the beneficial effects of exercise on health and performance. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 1228, 3-22.

- Goins, R. T., Williams, K. A., Carter, M. W., Spencer, S. M., & Solovieva, T. (2005). Perceived barriers to health care access among rural older adults: a qualitative study. The Journal of Rural Health, 21(3), 206-213.

- Islam, F. M. A., Islam, M. A., Hosen, M. A., Lambert, E. A., Maddison, R., Lambert, G. W., & Thompson, B. R. (2023). Associations of physical activity levels, and attitudes towards physical activity with blood pressure among adults with high blood pressure in Bangladesh. PloS One, 18(2), e0280879.

- Mattson, J. (2011). Transportation, distance, and health care utilization for older adults in rural and small urban areas. Transportation Research Record, 2265(1), 192-199.

- Zhang, X., Dupre, M. E., Qiu, L., Zhou, W., Zhao, Y., & Gu, D. (2017). Urban-rural differences in the association between access to healthcare and health outcomes among older adults in China. BMC Geriatrics, 17, 151.

- Hu, H., Cao, Q., Shi, Z., Lin, W., Jiang, H., & Hou, Y. (2018). Social support and depressive symptom disparity between urban and rural older adults in China. Journal of Affective Disorders, 237, 104-111.

- Jin, X., Liu, H., & Niyomsilp, E. (2023). The impact of physical activity on depressive symptoms among urban and rural older adults: empirical study based on the 2018 CHARLS database. Behavioral Sciences, 13(10), 864.

- Hidalgo, J. L. T., & Sotos, J. R. (2021). Effectiveness of physical exercise in older adults with mild to moderate depression. Annals of Family Medicine, 19(4), 302-309. 4).

- Yu, D. J., Yu, A. P., Leung, C. K., Chin, E. C., Fong, D. Y., Cheng, C. P., ... & Siu, P. M. (2023). Comparison of moderate and vigorous walking exercise on reducing depression in middle-aged and older adults: A pilot randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Sport Science, 23(6), 1018-1027.

- Song, D., & Doris, S. F. (2019). Effects of a moderate-intensity aerobic exercise programme on the cognitive function and quality of life of community-dwelling elderly people with mild cognitive impairment: a randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 93, 97-105.

- Cremers, G., Taylor, E., Hodge, L., & Quigley, A. (2022). Effectiveness and acceptability of low-intensity psychological interventions on the well-being of older adults: a systematic review. Clinical Gerontologist, 45(2), 214-234.

- Jia, X., Yu, Y., Xia, W., Masri, S., Sami, M., Hu, Z., ... & Wu, J. (2018). Cardiovascular diseases in middle aged and older adults in China: the joint effects and mediation of different types of physical exercise and neighborhood greenness and walkability. Environmental Research, 167, 175-183.

- Liu, L. J., & Guo, Q. (2007). Loneliness and health-related quality of life for the empty nest elderly in the rural area of a mountainous county in China. Quality of Life Research, 16, 1275-1280.

- Yue, L., Lin, H., Qin, L., Gui-Zhen, Q., Huan, Z., & Shan, Z. (2021). Moderating effect of psychological resilience on the perceived social support and loneliness in the left-behind elderly in rural areas. Front Nurs, 8, 357-63.

- Shvedko, A., Whittaker, A. C., Thompson, J. L., & Greig, C. A. (2018). Physical activity interventions for treatment of social isolation, loneliness or low social support in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 34, 128-137.

- Han, T., Han, M., Moreira, P., Song, H., Li, P., & Zhang, Z. (2023). Association between specific social activities and depressive symptoms among older adults: A study of urban-rural differences in China. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1099260.

- Carpes, L., Costa, R., Schaarschmidt, B., Reichert, T., & Ferrari, R. (2022). High-intensity interval training reduces blood pressure in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Experimental Gerontology, 158, 111657.

- Sobngwi, E., Mbanya, J. C., Unwin, N. C., Kengne, A. P., Fezeu, L., Minkoulou, E. M., ... & Alberti, K. G. M. M. (2002). Physical activity and its relationship with obesity, hypertension and diabetes in urban and rural Cameroon. International Journal of Obesity, 26(7), 1009-1016.

- Zhu, W., Chi, A., & Sun, Y. (2016). Physical activity among older Chinese adults living in urban and rural areas: a review. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 5(3), 281-286.

- Xiang, L., Yang, J., Yamada, M., Shi, Y., & Nie, H. (2025). Association between chronic diseases and depressive inclinations among rural middle-aged and older adults. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 7784.

- Kim, S., Lee, E. J., & Kim, H. O. (2021). Effects of a physical exercise program on physiological, psychological, and physical function of older adults in rural areas. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8487.

- Liu, Y., Huang, L., Liu, Q., Qian, G.Z., Zou, H. & Zhang, S (2021). Moderating effect of psychological resilience on the perceived social support and loneliness in the left-behind elderly in rural areas. Frontiers of Nursing, 8(4), 357-363.

- Halepoto, D. M., Elamin, N. E., Alhowikan, A. M., Halepota, A. T., & AL-Ayadhi, L. Y. (2024). Impact of physical exercise on behavioral and social features in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Pedagogy of Physical Culture and Sports, 28(3), 239-248.

- Rueggeberg, R., Wrosch, C., & Miller, G. E. (2012). The different roles of perceived stress in the association between older adults' physical activity and physical health. Health Psychology, 31(2), 164-171.

- Figueira, H. A., Figueira, O. A., Figueira, A. A., Figueira, J. A., Polo-Ledesma, R. E., Lyra da Silva, C. R., & Dantas, E. H. M. (2023). Impact of physical activity on anxiety, depression, stress and quality of life of the older people in Brazil. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1127.

- Firth, J., Rosenbaum, S., Stubbs, B., Gorczynski, P., Yung, A. R., & Vancampfort, D. (2016). Motivating factors and barriers towards exercise in severe mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 46(14), 2869-2881.

- Delle Fave, A., Bassi, M., Boccaletti, E. S., Roncaglione, C., Bernardelli, G., & Mari, D. (2018). Promoting well-being in old age: The psychological benefits of two training programs of adapted physical activity. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 828.

- Schmidt, L. L., Johnson, S., Genoe, M. R., Jeffery, B., & Crawford, J. (2021). Social interaction and physical activity among rural older adults: a scoping review. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 30(3), 495-509.

| Variables | Urban | Rural | P-value | |||

| Hypertention experience rate | Hypertention inexperience rate | Hypertention experience rate | Hypertention inexperience rate | |||

| Vigorous PA | Participant | 64(4.5%) | 73(5.2%) | 610(15.0%) | 743(18.3%) | 3.422(0.064) |

| Non-participant | 704(49.7%) | 576(40.6%) | 1,496(36.8%) | 1,215(29.9%) | 36.859(0.000) | |

| Moderate PA | Participant | 339(23.9%) | 315(22.2%) | 867(21.3%) | 942(23.2%) | 2.735(0.098) |

| Non-participant | 429(30.3%) | 334(23.6%) | 1,239(30.5%) | 1,016(25.0%) | 19.799(0.000) | |

| Low PA | Participant | 640(45.2%) | 561(39.6%) | 1,502(37.0%) | 1,405(34.6%) | 2.629(0.105) |

| Non-participant | 128(9.0%) | 88(6.2%) | 604(14.9%) | 553(13.6%) | 0.095(0.758) | |

| Total | 768(54.2%) | 649(45.8%) | 2,106(51.8%) | 1,958(48.2%) | ||

| Variables | Urban | Rural | P-value | |||

| Diabetes experience rate | Diabetes inexperience rate | Diabetes experience rate | Diabetes inexperience rate | |||

| Vigorous PA | Participant | 28(2.0%) | 109(7.7%) | 189(4.7%) | 1,164(28.6%) | 2.081(0.149) |

| Non-participant | 334(23.6%) | 946(66.8%) | 476(11.7%) | 2,235(55.0%) | 8.495(0.004) | |

| Moderate PA | Participant | 158(1.2%) | 496(35.0%) | 281(6.9%) | 1,528(37.6%) | 1.230(0.267) |

| Non-participant | 204(14.4%) | 559(39.4%) | 384(9.4%) | 1,871(46.0%) | 1.640(0.200) | |

| Low PA | Participant | 310(21.9%) | 891(62.9%) | 484(11.9%) | 2,423(59.6%) | 0.291(0.590) |

| Non-participant | 52(3.7%) | 164(11.6%) | 181(4.5%) | 976(24.0%) | 0.611(0.434) | |

| Total | 362(25.5%) | 1,055(74.5%) | 665(16.4%) | 3,399(83.6%) | ||

| Variables | Urban | Rural | P-value | |||

| Heart disease experience rate | Heart disease inexperience rate | Heart disease experience rate | Heart disease inexperience rate | |||

| Vigorous PA | Participant | 35(2.5%) | 102(7.2%) | 296(7.3%) | 1,057(26.0%) | 10.577(0.001) |

| Non-participant | 509(35.9%) | 771(54.4%) | 823(20.3%) | 1,888(46.5%) | 32.532(0.000) | |

| Moderate PA | Participant | 226(15.9%) | 428(30.2%) | 477(11.7%) | 1,332(32.8%) | 7.550(0.006) |

| Non-participant | 318(22.4%) | 445(31.4%) | 642(15.8%) | 1,613(39.7%) | 2.223(0.136) | |

| Low PA | Participant | 453(32.0%) | 748(52.8%) | 790(19.4%) | 2,117(52.1%) | 1.506(0.220) |

| Non-participant | 91(6.4%) | 125(8.8%) | 329(8.1%) | 828(20.4%) | 0.658(0.417) | |

| Total | 544(38.4%) | 873(61.6%) | 1,119(27.5%) | 2,945(72.5%) | ||

| Variables | Urban | Rural | P-value | |||

| Stroke experience rate | Stroke inexperience rate | Stroke experience rate | Stroke inexperience rate | |||

| Vigorous PA | Participant | 14(1.0%) | 123(8.7%) | 120(3.0%) | 1,233(30.3%) | 0.888(0.346) |

| Non-participant | 167(11.8%) | 1,113(78.5%) | 354(8.7%) | 2,357(58.0%) | 15.370(0.000) | |

| Moderate PA | Participant | 65(4.6%) | 589(41.6%) | 175(4.3%) | 1,634(40.2%) | 8.759(0.003) |

| Non-participant | 116(8.2%) | 647(45.7%) | 299(7.4%) | 1,956(48.1%) | 12.525(0.000) | |

| Low PA | Participant | 152(10.7%) | 1,049(74.0%) | 329(8.1%) | 2,578(63.4%) | 0.097(0.755) |

| Non-participant | 29(2.0%) | 187(13.2%) | 145(3.6%) | 1,012(24.9%) | 1.186(0.276) | |

| Total | 181(12.8%) | 1,236(87.2%) | 474(11.7%) | 3,590(88.3%) | ||

| Variables | N | Urban | Rural | F value | |

| Vigorous PA | Participant | 1,490 | 7.270±6.056 | 10.370±6.505 | 0.543(0.596)74.183(0.074)1.074(0.300) |

| Non-participant | 3,991 | 7.830±6.080 | 10.280±6.683 | ||

| Moderate PA | Participant | 2,463 | 7.170±5.755 | 10.370±6.718 | 0.698(0.557)17.944(0.148)9.232(0.002) |

| Non-participant | 3,018 | 8.290±6.300 | 10.270±6.548 | ||

| Low PA | Participant | 4,108 | 7.410±5.911 | 10.140±6.586 | 2.738(0.346)4.192(0.289)11.503(0.001) |

| Non-participant | 1,373 | 9.790±6.596 | 10.730±6.701 | ||

| Variables | Urban | Vigorous PA | Moderate PA | Low PA | Hypertension | Diabetes | Heart Disease | Stroke | Depression |

| Urban | 1 | ||||||||

| Vigorous PA | -.207** | 1 | |||||||

| Moderate PA | .037** | .208** | 1 | ||||||

| Low PA | .156** | 0.025 | .175** | 1 | |||||

| Hypertension | 0.021 | -.095** | -.069** | -0.011 | 1 | ||||

| Diabetes | .103** | -.071** | -0.025 | 0.024 | .205** | 1 | |||

| Heart Disease | .103** | -.112** | -.033* | -0.005 | .207** | .170** | 1 | ||

| Stroke | 0.015 | -.059** | -.062** | -0.011 | .164** | .094** | .131** | 1 | |

| Depression | -.169** | .030* | -.027* | -.089** | .097** | .076** | .147** | .107** | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).