1. Introduction

The emergence of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) necessitated the rapid development and deployment of vaccines and therapeutic agents. A critical component in evaluating the effectiveness of these interventions is the use of neutralization assays, which measure the ability of antibodies to inhibit virus infection. By measuring the neutralizing activity, researchers can determine the potency and duration of immune responses elicited by the vaccine candidates, guiding modifications and improvements in their formulation[

1,

2]. Additionally, understanding variations in neutralization efficacy against emerging variants of the virus is vital for ensuring long-term protection and effectiveness of the developed vaccines and therapeutics[

3,

4,

5,

6].

Traditional neutralization assays with live viruses directly measure antibody effectiveness against actual pathogens and are considered the gold standard for evaluating neutralizing antibodies[

7,

8]. However, live virus neutralization assays (LVNAs) pose several challenges, such as biosafety issues and the need for high-level containment. To overcome these limitations, pseudotyped virus neutralization assays (PVNAs) use non-pathogenic viruses that express the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, allowing for a safe simulation of viral entry. Core viruses like vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) and lentiviruses (e.g., HIV-1) are commonly used, making PVNAs suitable for biosafety level-2 (BSL-2) laboratories, unlike live virus assays that require BSL-3[

9,

10]. PVNAs enable high-throughput screening and adaptability for various strains, which is important for rapidly evolving pathogens.

It is essential to recognize that discrepancies may exist between PVNAs and LVNAs. These differences can stem from variations in the viral life cycle, entry efficiency, and cellular tropism. While PVNAs are useful for initial screening and mechanistic studies, they should be validated with LVNAs to ensure relevance to natural infections. Understanding the correlation between the two is crucial for validating PVNAs as a reliable proxy for LVNAs in vaccine and therapeutic development. Previous studies have shown varying degrees of concordance[

8,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Most of these studies analyzed the correlation based on small sample sizes, and used serum samples from COVID-19 convalescents instead of vaccinated individuals. Additionally, only several of them evaluated the correlation across different variants[

8,

15,

16].

This post-hoc analysis aimed to evaluate the correlation between a PVNA and an LVNA in a phase I/II clinical trial that evaluated a bivalent protein-based COVID-19 vaccine, providing insights into their relative performance and reliability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This comprehensive post-hoc analysis examined data from a Phase I/II clinical trial of vaccine interventions. Phase I assessed the safety of different dose levels of a vaccine in healthy volunteers, while Phase II evaluated its effectiveness in a larger, diverse population, monitoring safety. Participants who had neither been infected with SARS-CoV-2 nor received any SARS-CoV-2 vaccines were included. They all received two doses of SCTV01C as part of their primary series vaccination. SCTV01C is a recombinant bivalent vaccine comprised of the trimeric spike extracellular domain (S-ECD) of SARS-CoV-2 variants Alpha and Beta, and adjuvanted with SCT-VA02B, a squalene-based oil-in-water emulsion. Immunogenicity was evaluated pre-and post-vaccination by detecting the titers of neutralizing antibodies. The primary results of this clinical trial have been published[

17,

18]. This analysis aimed to uncover correlations between neutralizing antibody results from LVNA and PVNA across different SARS-CoV-2 variants.

2.2. Neutralization Assays

Neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 Alpha, Beta, and Delta variants were measured using LVNA and PVNA.

SARS-CoV-2 Microneutralization Assay

The live virus neutralizing antibodies were measured using a microneutralization assay (MNA) and have been described previously[

17]. Sera were diluted serially in duplicate, starting at 1:8, and then mixed with live virus for incubation. This mixture was then tested on susceptible cell cultures for signs of viral infection. The neutralization titers were defined as the reciprocal of the highest dilution that protected 50% of wells (MN50) and were calculated using the Reed-Muench equation.

SARS-CoV-2 Pseudotyped Virus Neutralization Assay

The establishment and validation of the SARS-CoV-2 pseudotyped virus neutralization assay have been reported[

9,

19]. A pseudovirus was produced using a VSV pseudovirus production system. Sera were diluted serially, starting at 1:30, and then mixed with pseudotyped virus, followed by incubation. The mixture was then incubated with target cells, and the virus infecting the target cells was measured by detecting the expression of luciferase. The half maximal effective concentration (EC50) titers were calculated based on uninfected cells as 100% neutralization. Reciprocal EC50 geometric mean titers (GMT) were also determined.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Among all the serum samples (before or after baseline) from the analysis population, those with both LVNA and PVNA test results under the same SARS-CoV-2 variant (Alpha, Beta, or Delta) were selected for analysis. Moreover, the results of the three SARS-CoV-2 variants were analyzed separately. The statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software (version 9.4). In calculating specificity, sensitivity, and accuracy, antibody titers against SARS-CoV-2 equal or greater than the lower limit of quantitation were labeled as “Positive,” while those below were labeled as “Negative.” The antibody titers of LVNA were taken as the reference (“true”) results, and the misclassifications were counted and displayed in an error matrix table. The Pearson correlation coefficient and a linear regression model were used to measure the strength of the relationship between PVNA and LVNA. All antibody titers were log-transformed to the base 10 before calculation.

To evaluate the agreement between PVNA and LVNA, a Bland–Altman plot[

20] and a Kernel density plot were plotted. The Bland–Altman plot is a scatter plot of the mean PVNA and LVNA at each measurement point, along with their differences. The PVNA and LVNA were log-transformed to the base 10 before calculating the mean and difference. The 95% limits of agreement (LOAs) and the maximum acceptable difference (MAD) were calculated. The LOAs were constructed as a V-shaped limit[

21], and the MAD was set to 0.5 times the LVNT. If the observed PVNA-LVNA difference is below the MAD value, it is considered that the difference has no significant biological effect. The Gaussian kernel is chosen to plot the kernel density plot, which describes the probability distribution of the fold increase relative to the baseline of antibody titers after baseline. The fold increase was log-transformed to base 10 when plotted.

3. Results

3.1. The Neutralizing Antibody Titers

Descriptive analysis was performed on all the serum samples, categorized by the sampling visit times, assay methods, and corresponding variants. The GMT and its 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each category, and the results are listed in

Table 1. It can be seen that at baseline, almost all the antibody titers were below the lower limit of quantitation. At the first sampling visit after the second vaccination, the antibody titer levels showed a significant increase compared to baseline, followed by a gradual decrease over time. However, the neutralizing antibodies increased significantly 365 days after vaccination. The possible reasons might include known or unknown SARS-CoV-2 infection and close contact with COVID-19 individuals during the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic due to the decline of neutralizing antibodies and the emergence of new variants.

3.2. The Error Matrix

The number of serum samples tested for the Alpha, Beta, and Delta variants was 324, 324, and 505, respectively, with the results shown in

Table 2. It can be seen that the PVNA has a very high sensitivity for LVNA. In detecting all three variants, only one LVNA-positive sample was negative in the PVNA test. The specificity of PVNA for LVNA was also good, with a specificity greater than 90% for all three variants. The accuracy of PVNA for LVNA was 98.8%, 99.1%, and 94.3% for the Alpha, Beta, and Delta variants, respectively, reflecting the high consistency in the test results.

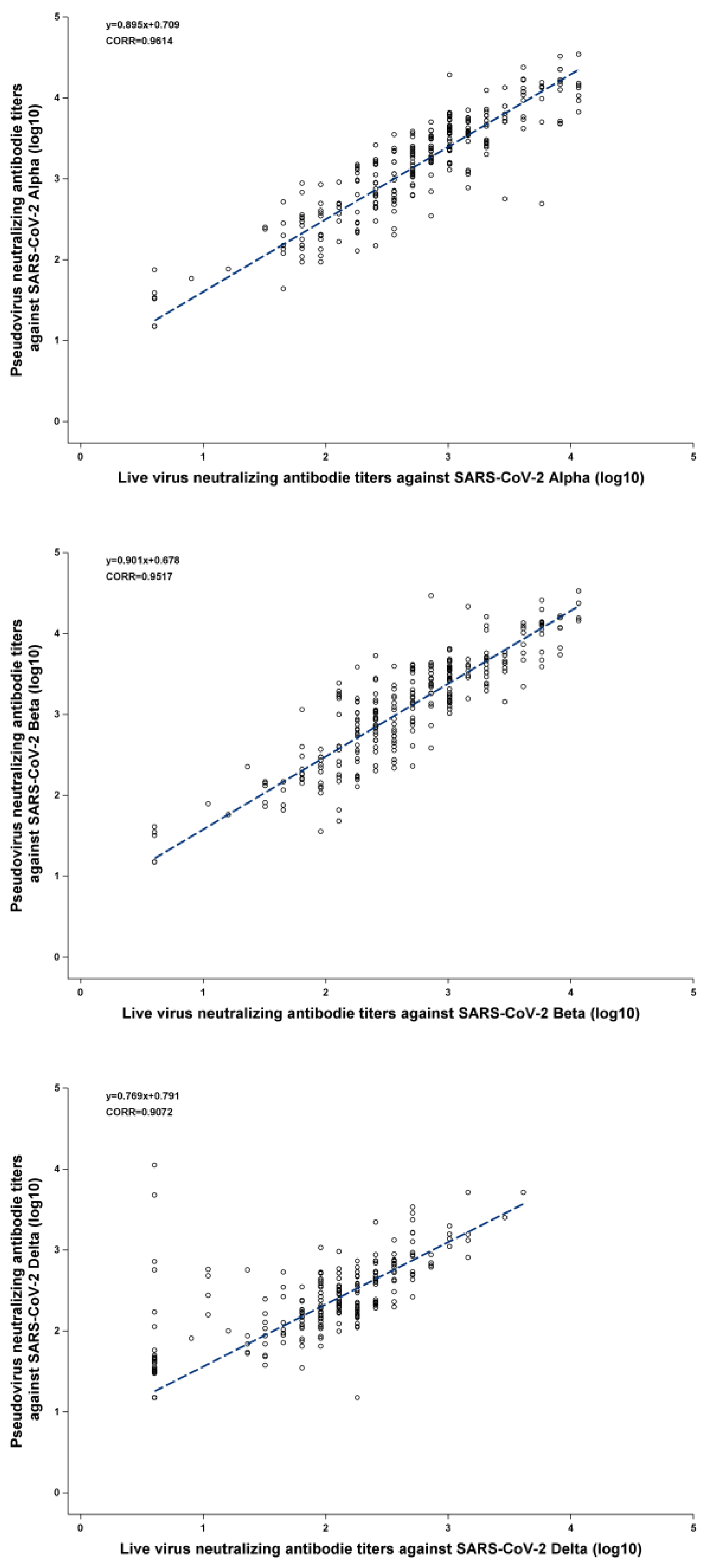

3.3. The Correlation between PVNA and LVNA

The Pearson correlation coefficients between PVNA and LVNA were 0.9614, 0.9517, and 0.9072 for the Alpha, Beta, and Delta variants, respectively, indicating that PVNA and LVNA have a strong positive correlation.

Figure 1(A) and

Figure 1(B) show that almost all the points are distributed near the regression line, indicating a strong linear relationship between PVNA and LVNA after log transformation. As shown in

Figure 1(C), although most points were distributed near the regression line, there were some points where the titers of LVNA were below the lower limit of quantitation, while those of PVNA remained high. This resulted in a weaker correlation between LVNA and PVNA in the Delta variant compared to the Alpha and Beta variants.

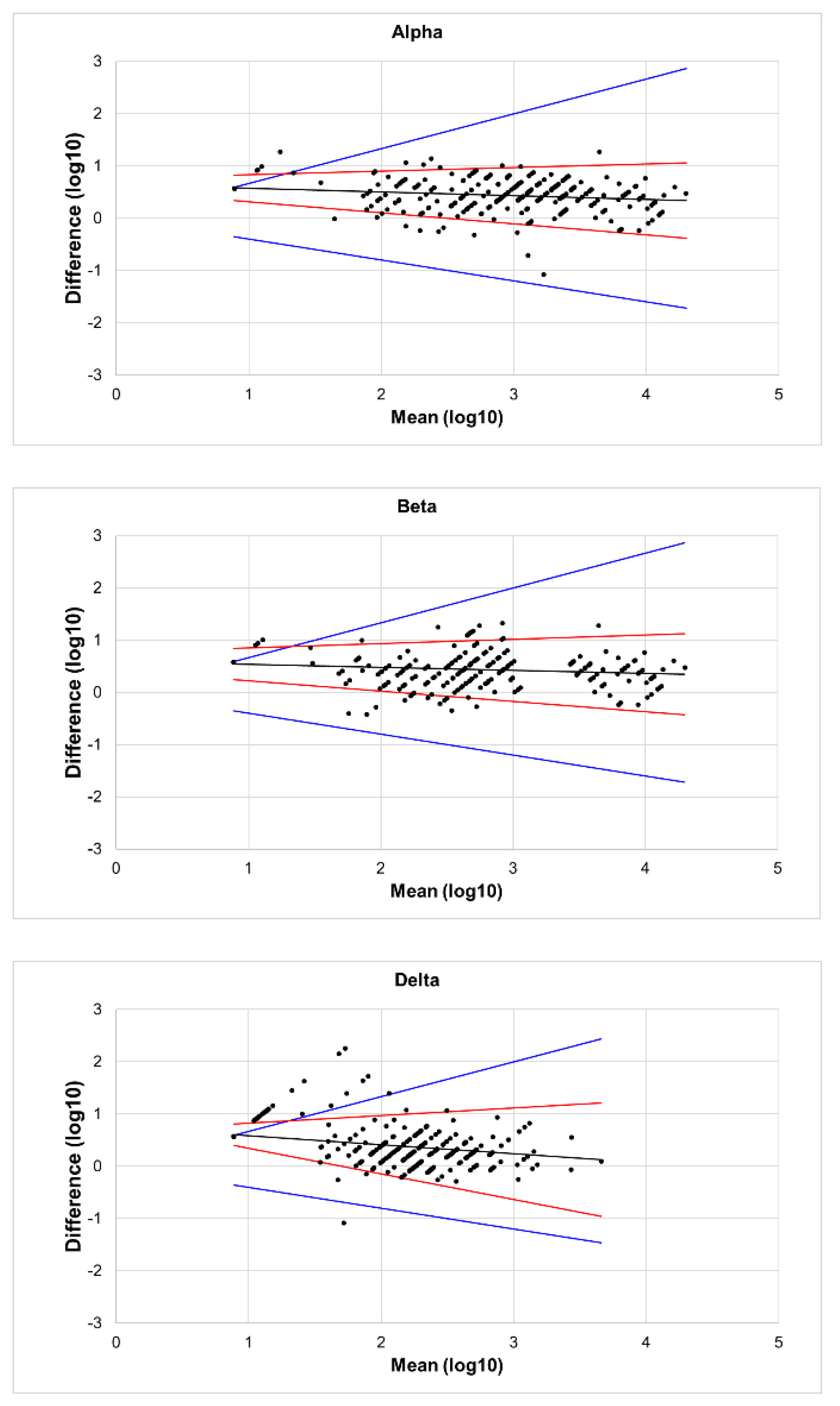

3.4. Bland-Altman Analysis

The results of the Bland–Altman analysis are shown in

Figure 2. Almost all the points in the figures were distributed close to the regression line, and the difference did not increase as the mean increased. Additionally, the angle between the two LOA lines was very small, indicating good agreement between PVNT and LVNT. In

Figure 2(A) and

Figure 2(B), only a few points lay outside the range of the MAD, with very few outliers. However, in

Figure 2(C), several points appeared above the MAD. Compared to

Figure 1, it can be seen that these points correspond to the serum samples where titers of LVNA were below the lower limit of quantitation, but those of PVNA still had a detectable value. Aside from these points, the rest showed high agreement between PVNA and LVNA.

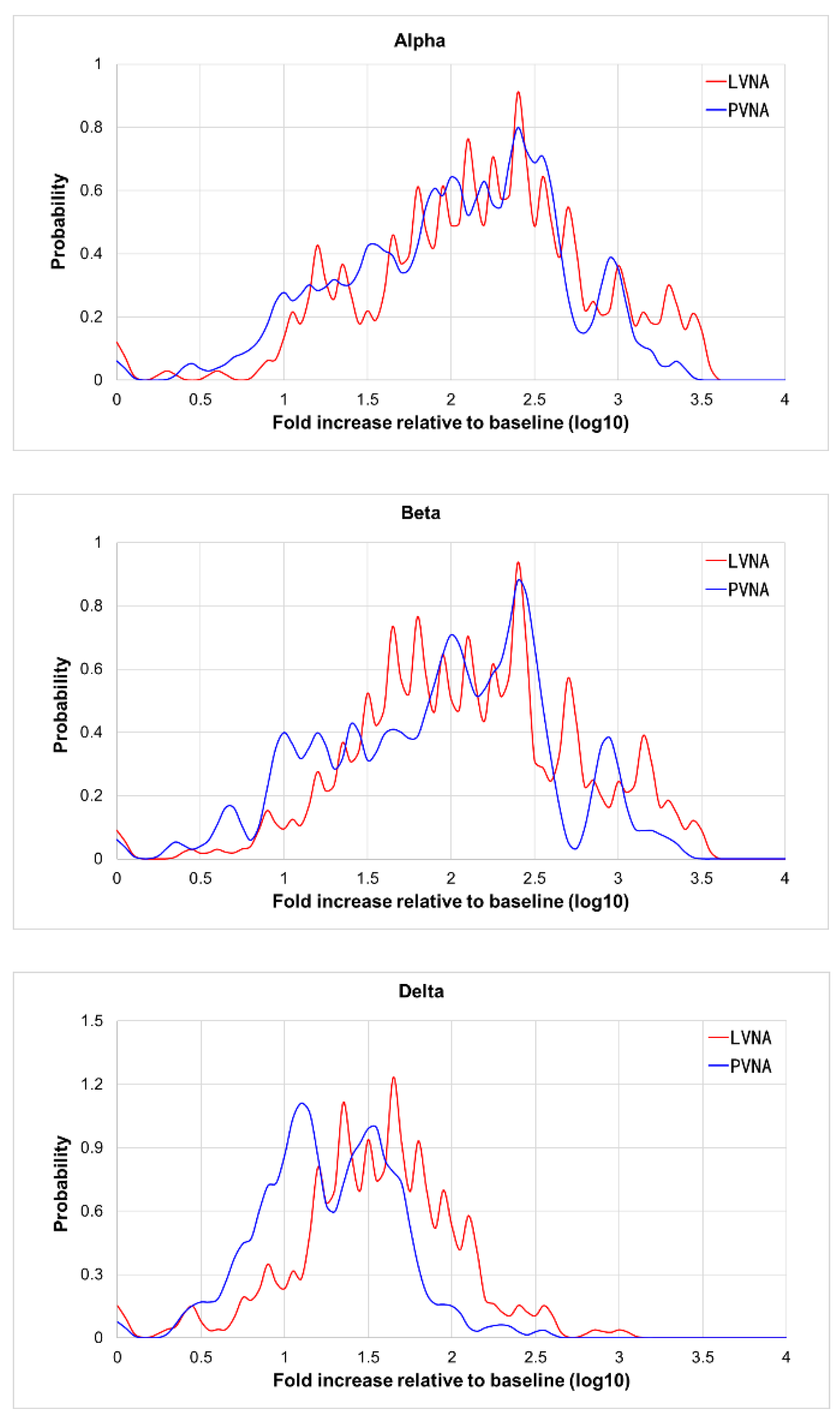

3.5. The Probability Distribution of the Fold Increase Relative to the Baseline of PVNA and LVNA

As shown in

Table 1, the GMT of PVNA was higher than that of LVNA. Considering the differences in assay methods, the fold increase relative to baseline was used to analyze the agreement between PVNA and LVNA.

Figure 3(A) and

3(B) showed that the distribution curves of PVNA results overlap almost entirely with those of LVNA, indicating good agreement between PVNA and LVNA for Alpha and Beta variants. In

Figure 3C, the curves of PVNA and LVNA were similar in shape but do not overlap, with the relative baseline fold increase of PVNA being slightly lower than that of LVNA. The agreement of fold increase relative to baseline between PVNA and LVNA for the Delta variant was slightly lower than that for the Alpha and Beta variants.

4. Discussion

Antibody detection and quantification methods are crucial for assessing immune response post-infection or vaccination. While LVNA directly evaluates neutralizing capability in an infectious context, its application faces several challenges, such as stringent safety protocols, regulatory constraints, and variability in viral strain availability[

22]. These limitations hinder the scope and frequency of experimental studies, ultimately affecting the efficiency of vaccine and therapeutic development efforts[

23]. In contrast, PVNA demonstrates notable advantages, including increased safety, accessibility, and versatility in testing for various viral threats, such as SARS-CoV-2[

24], HIV[

25], HPV[

26], Influenza[

27], and others. These characteristics illustrate the growing preference for PVNA in virology, providing a vital tool for advancing our understanding of viral infections and immune responses[

28,

29]. This has been accepted as an assay for the assessment of immunogenicity endpoints in the FDA guidance for vaccines to prevent COVID-19[

30]. Understanding the correlation between LVNA and PVNA is important for evaluating whether pseudotyped assays can effectively replace live virus assays in viral testing. This knowledge ensures both the practicality of testing methods and the safety involved, as working with live viruses carries significant risks. Our findings indicate a significant alignment between these methods, while also highlighting essential nuances for researchers in vaccine development and therapeutic evaluations.

We employed various statistical methods to analyze the correlation between LVNA and PVNA. The consistency observed across these different approaches provides a robust foundation for understanding the relationship between the two methodologies. As shown in

Table 2, the analysis of PVNA versus LVNA for SARS-CoV-2 variants, Alpha, Beta, and Delta, demonstrated that the sensitivity and specificity of PVNA exceeded 90% for all variants, indicating its potential as a robust and reliable tool for assessing neutralizing antibody responses in populations exposed to SARS-CoV-2. Furthermore, the accuracy rates recorded were 98.8% for Alpha, 99.1% for Beta, and 94.3% for Delta. These results underscored the effectiveness of PVNA in distinguishing neutralization capabilities against these variants. The Pearson correlation coefficients of 0.9614 for Alpha and 0.9517 for Beta demonstrated that PVNA could effectively replicate the neutralization dynamics of live viruses in controlled settings. Conversely, the correlation for Delta (0.9072) was a little weaker, suggesting potential variability in neutralization capabilities, which warrants further investigation into the impact of specific mutations in this variant. Bland-Altman analysis further supports the reliability of PVNA, showing good agreement with LVNA results. We visualized any systematic bias and identified outliers by plotting the difference between LVNA and PVNA results against their average. Our analysis revealed minimal bias and narrow limits of agreement, indicating that the discrepancies between the two methods are generally small and random. Notably, while the geometric mean titer (GMT) of PVNA was higher than that of LVNA for the Delta variant, the slightly lower fold increase in titers of PVNA may indicate that certain mutations in the spike protein of Delta could reduce the efficacy of neutralization. Future research should continue to refine these methodologies to enhance their predictive accuracy and broaden their applicability in vaccine development and evaluation.

It is important to interpret the correlation between PVNA and LVNA carefully. While our findings support PVNA's reliability, differences in methodology - such as the use of engineered particles versus live viruses - can affect neutralization effectiveness. These variations may be due to differing biological testing contexts and immune responses. PVNA utilizes recombinant, replication-deficient viruses engineered to express SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins on their surface. The ability of antibodies to neutralize viruses may not fully translate from pseudotyped to live viruses due to the complex interactions present in live viral infections[

8,

14,

31].

There are some limitations in our study. Firstly, neutralizing antibodies against Omicron were not evaluated, and the impact of new mutations on the correlation between these methods remains to be investigated. Secondly, the LVNA and PVNA were not performed by the same experimenter, which may introduce additional errors due to the differences in procedure and data reading.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, while LVNA provides a precise measure of vaccine-induced immunity, PVNA offers benefits in safety, cost, and scalability. It is important to understand the strengths and limitations of both methods for effective vaccine evaluation, especially with new SARS-CoV-2 variants. Future research should aim to enhance PVNA techniques to better represent natural infections and improve accuracy for various viral strains. By combining efforts, both approaches can accelerate the development of effective vaccines against evolving pathogens.

Author Contributions

Cuige Gao contributed to the formulated the research questions and methodological framework. Jiang Yi contributed to the statistical analysis. Adam Abdul Hakeem Baidoo contributed to manuscript drafting. Dongfang Liu, Jian Li, Qiang Zhou and Liangzhi Xie revised the manuscript.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Sinocelltech Ltd., and funded by National Key Research and Development Program of China [2023YFC2307801], National Key Research and Development Program of China [2022YFC0870600], and Beijing Science and Technology Planning Project [Z221100007922012].

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the main manuscript or the supplementary material. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to L.X. (lx@sinocelltech.com).

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SARS-CoV-2 |

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| LVNA |

Live virus neutralization assays |

| PVNA |

Pseudotyped virus neutralization assays |

| VSV |

Vesicular stomatitis virus |

| BSL-2 |

Biosafety level-2 |

| S-ECD |

Spike extracellular domain |

| MNA |

Microneutralization assay |

| GMT |

Geometric mean titers |

| LOA |

Limits of agreement |

| MAD |

Maximum acceptable difference |

References

- Liu KT, Han YJ, Wu GH, Huang KA, Huang PN. Overview of Neutralization Assays and International Standard for Detecting SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibody. Viruses 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Gattinger P, Ohradanova-Repic A, Valenta R. Importance, Applications and Features of Assays Measuring SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibodies. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Núñez JJ, Muñoz-Valle JF, Torres-Hernández PC, Hernández-Bello J. Overview of Neutralizing Antibodies and Their Potential in COVID-19. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9 (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Huang W, Xiang H, Nie J. SARS-CoV-2 Neutralization Assays Used in Clinical Trials: A Narrative Review. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Tegally H, Wilkinson E, Giovanetti M, et al. Detection of a SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern in South Africa. Nature 2021, 592, 438–443. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang P, Nair MS, Liu L, et al. Antibody resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.351 and B.1.1.7. Nature 2021, 593, 130–135. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantoni D, Mayora-Neto M, Temperton N. The role of pseudotype neutralization assays in understanding SARS CoV-2. Oxf Open Immunol (In eng). 2021, 2, iqab005. [CrossRef]

- D'Apice L, Trovato M, Gramigna G, et al. Comparative analysis of the neutralizing activity against SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan-Hu-1 strain and variants of concern: Performance evaluation of a pseudovirus-based neutralization assay. Front Immunol (In eng). 2022, 13, 981693. [CrossRef]

- Nie J, Li Q, Wu J, et al. Establishment and validation of a pseudovirus neutralization assay for SARS-CoV-2. Emerg Microbes Infect (In eng). 2020, 9, 680–686. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Huang W, Xiang H, Nie J. SARS-CoV-2 Neutralization Assays Used in Clinical Trials: A Narrative Review. Vaccines 2024, 12, 554. Available online: (https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/12/5/554). [CrossRef]

- James J, Rhodes S, Ross CS, et al. Comparison of Serological Assays for the Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies. Viruses (In eng). 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- ewley KR, Coombes NS, Gagnon L, et al. Quantification of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody by wild-type plaque reduction neutralization, microneutralization and pseudotyped virus neutralization assays. Nat Protoc (In eng). 2021, 16, 3114–3140. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyseni I, Molesti E, Benincasa L, et al. Characterisation of SARS-CoV-2 Lentiviral Pseudotypes and Correlation between Pseudotype-Based Neutralisation Assays and Live Virus-Based Micro Neutralisation Assays. Viruses (In eng). 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Cantoni D, Wilkie C, Bentley EM, et al. Correlation between pseudotyped virus and authentic virus neutralisation assays, a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Frontiers in Immunology (Systematic Review) (In English). 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen D, Xiao J, Simmonds P, et al. Effects of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Strain Variation on Virus Neutralization Titers: Therapeutic Use of Convalescent Plasma. J Infect Dis (In eng). 2022, 225, 971–976. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Zhang L, Fu W, et al. Optimization and validation of a virus-like particle pseudotyped virus neutralization assay for SARS-CoV-2. MedComm (2020) (In eng). 2024, 5, e615. [CrossRef]

- Wang G, Zhao K, Han J, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a bivalent SARS-CoV-2 recombinant protein vaccine, SCTV01C in unvaccinated adults: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase I clinical trial. J Infect 2023, 86, 154–225. [CrossRef]

- Wang G, Zhao K, Zhao X, et al. Sustained immunogenicity of bivalent protein COVID-19 vaccine SCTV01C against antigen matched and mismatched variants. Expert Rev Vaccines 2025, 24, 128–137. [CrossRef]

- Nie J, Li Q, Wu J, et al. Quantification of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody by a pseudotyped virus-based assay. Nat Protoc 2020, 15, 3699–3715. [CrossRef]

- Bland JM, Altman DG. Measuring agreement in method comparison studies. Stat Methods Med Res 1999, 8, 135–60. [CrossRef]

- Ludbrook, J. Confidence in Altman-Bland plots: a critical review of the method of differences. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2010, 37, 143–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention NIoH. Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories. 2020.

- Organization WH. Laboratory biosafety guidance related to SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): Interim guidance, 11 March 2024. 2024. 11 March.

- Yang R, Huang B, A R, et al. Development and effectiveness of pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 system as determined by neutralizing efficiency and entry inhibition test in vitro. Biosafety and Health 2020, 2, 226–231. [CrossRef]

- Sarzotti-Kelsoe M, Bailer RT, Turk E, et al. Optimization and validation of the TZM-bl assay for standardized assessments of neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1. J Immunol Methods 2014, 409, 131–46 (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Krajden M, Cook D, Yu A, et al. Assessment of HPV 16 and HPV 18 antibody responses by pseudovirus neutralization, Merck cLIA and Merck total IgG LIA immunoassays in a reduced dosage quadrivalent HPV vaccine trial. Vaccine 2014, 32, 624–30 (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Carnell GW, Ferrara F, Grehan K, Thompson CP, Temperton NJ. Pseudotype-based neutralization assays for influenza: a systematic analysis. Front Immunol 2015, 6, 161 (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Xiang Q, Li L, Wu J, Tian M, Fu Y. Application of pseudovirus system in the development of vaccine, antiviral-drugs, and neutralizing antibodies. Microbiol Res 2022, 258, 126993 (In eng). [CrossRef]

- Tolah AMK, Sohrab SS, Tolah KMK, Hassan AM, El-Kafrawy SA, Azhar EI. Evaluation of a Pseudovirus Neutralization Assay for SARS-CoV-2 and Correlation with Live Virus-Based Micro Neutralization Assay. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Administration USFaD. Emergency Use Authorization for Vaccines to Prevent COVID-19: Guidance for Industry. 2022.

- Frische A, Brooks PT, Gybel-Brask M, et al. Optimization and evaluation of a live virus SARS-CoV-2 neutralization assay. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0272298. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).