Background

With the emergence of immune-evasive variants of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2), such as Delta and Omicron, the assessment of vaccine-induced humoral immunity has become increasingly complex. In addition, due to multiple previous infections with earlier variants and the sequential application of mono- and bivalent vaccines, the neutralizing activity of serum antibodies against those variants may vary considerably among individuals [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Consequently, the profiles of variant-specific antibodies cannot be adequately assessed by commercial assays that only measure antibody binding to the wild-type (WT) spike protein [

5].

Live virus neutralization tests (NTs) are considered the gold standard for analyzing neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) against multiple variants, including the Omicron subvariants (e.g., BA.1, BA.2, BA.5) [

1,

2,

6,

7]. However, these tests are work-intensive, slow, and require laboratories with high biosafety levels. Therefore, we and others evaluated variant-adapted surrogate virus neutralization tests (sVNTs) that quantify the antibody-mediated binding inhibition of the viral receptor-binding-domain (RBD) to its cellular receptor [angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)] [

8,

9,

10].

In that regard, microarrays are particularly suitable as sVNT, because the combination of multiple RBD proteins of different SARS-CoV-2 variants can be plotted as the target antigens into a single well, providing simultaneous measurement of antibody-mediated inhibition of ACE2 binding to the RBDs, which substitutes for multiple variant-specific virus neutralization assays [

8,

9,

10].

However, nAb titers against different SARS-CoV-2 variants span a wide concentration range, which are assessed by using dilution series of the serum samples in live-virus NTs. In contrast, in sVNTs, only a single dilution of the sample is used to measure inhibition. The concentration of antibodies against the RBD of one specific variant in one sample may already reach saturation and cause complete inhibition of RBD-ACE2 binding, whereas antibodies against the RBD of another variant may still be in an optimal quantification range.

Thus, multivariant sVNTs require thorough evaluation with multiple serial serum dilutions and correlation between the variant-specific measurements with the respective titers of live-virus NTs in order to identify correct cut-off concentrations within the sVNT´s linear test range [

11].

To this end, we first evaluated a novel multivariant sVNT microarray using multiple variant-specific live virus NTs as reference. Then, we analyzed whether the increase in the breadth of variant-specific nAbs following Omicron-adapted vs monovalent wild-type booster was similarly quantifiable by the sVNT as compared with live-virus NTs. [

7,

12,

13]

Material and Methods

Sample Cohort

The study included 65 serum samples from our serum biobank of both SARS-CoV-2 vaccinated and infected individuals, and 30 additional pre-pandemic control samples from healthy individuals. Samples were drawn 15-40 days after the last vaccination or infection.

The first cohort included samples from individuals hospitalized for a SARS-CoV-2 wild-type infection in the early pandemic before vaccines were available (n = 18, median age: 48 years (y), range: 22-77 y). The second and third cohorts included sera drawn approximately one month after the individuals’ respective second (n = 11, median age: 40 y, range 20-81) or third (n = 14, median age: 46 y, range: 27 – 64 y) mRNA monovalent wild-type vaccination. The fourth and fifth cohorts included individuals who received three monovalent wild-type vaccinations plus one bivalent Omicron-adapted BA.1/WT booster vaccination (n = 9, median age: 52 years, range: 38-62 y) or BA.5/WT (n = 13, median age: 50 y, range: 32-57 y). Only one sample was included from each individual. Detailed cohort characteristics are provided in

Tables S1-2.

All vaccinated individuals reported that they had not been infected with SARS-CoV-2, and anti-nucleocapsid-antibodies were not detected in those cohorts (Anti-NC-IgG-ELISA, Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany). None of the individuals reported any immunosuppressive therapy or condition. Data from the live-virus NTs were previously reported and were included only as reference for the sVNT evaluated in this study [

2,

7].

Live virus NTs

As previously described, each serum was tested for nAbs against the WT (with the D614G mutation), Delta and Omicron BA.1, BA.2, and BA.5 SARS-CoV-2 subvariants [

2,

7,

14,

15].

In brief, SARS-CoV-2 variants were isolated from respiratory swabs taken from infected individuals using VeroE6 or VeroE6 TMPRSS2 cells (kindly provided by Anna Ohradanova-Repic). Virus sequences were determined using next-generation sequencing (Illumina) and uploaded to the GISAID database (WT, B.1.1 with the D614G mutation EPI_ISL_438123; Delta, B.1.617.2-like, sub-lineage AY.122:EPI_ISL_4172121; Omicron, B.1.1.529+BA.*, sub-lineage BA.1.17:EPI_ISL_9110894; Omicron, B.1.1.529+BA.*, sublineage BA.2:EPI_ISL_11110193; Omicron, B.1.1.529+BA.*, sub-lineage BA.5.3:EPI_ISL_15982848). The lineages were determined using Pango 4.1.3, Pango-data v.1.17.

Serum samples were serially diluted (two-fold) and incubated with 50-100 TCID50 SARS-CoV-2 for one hour at 37°C. The dilution series ranged from 1:10 to 1:10,240. This mixture was then applied to VeroE6 cells and incubated for 3-5 days at 37°C. Then, the cytopathic effect (CPE) was microscopically assessed, and the final titers were calculated as the inverse of the last titration at which CPE was prevented by serum-neutralizing activity.

Multivariant surrogate virus neutralization test

The multivariant surrogate sVNT was performed using a similar protocol as in a previous study [

9]. In brief, the basic framework of this assay is a commercial SARS-CoV-2 VoC ViraChip

® IgG microarray developed by Viramed (Planegg, Germany). However, in contrast to the standard version of the commercial microarray, the manufacturer plotted the RBD proteins of the SARS-Cov-2 wild-type (WT), the Delta variant, and the Omicron subvariants BA.1, BA.2, and BA.5 in triplets as the target antigens on the solid phase of each well, spatially separated into microspots.

After incubation of the wells with the diluted serum samples, recombinant ACE2 bound to alkaline phosphatase (ACE2-AP; also obtained from Viramed) was added to each well, which could only bind to the RBD proteins in inverse correlation to the levels of neutralizing antibodies against the specific SARS-CoV-2 variants and Omicron subvariants present in the samples (until complete inhibition was achieved at the specific dilution).

Finally, after a washing step, the bound ACE2-AP (if present) was made visible by a colorimetric reaction of a chromogen substrate and assessed by the Viramed plate reader. For each dilution step performed with each sample, the variant-specific ACE2-RBD binding inhibition was calculated as a percentage of reduction of the inhibited color reaction relative to the maximum uninhibited color reaction obtained from a negative buffer control sample (incubation without serum but with ACE2-AP) after subtraction of the background (i.e., 100 % represents complete inhibition of the binding).

Since neutralizing antibody titers against multiple variants in different serum samples covered a wide range (1:10 up to 1:2,560), no single serum dilution was suitable to obtain valid ACE2-RBD inhibition values for all variants simultaneously. Therefore, each sample was tested in five serial two-fold dilutions, starting from 1:20 up to 1:320. In some instances, , additional dilutions were required (up to 1:2,560). Next, all values representing a total inhibition (= 100 %) were discarded. Additionally, all values below 20 % were discarded for all dilutions except for 1:20 since preliminary data showed that this was below the assay’s linear range (and the error would have been amplified due to the dilutions). Then, we accounted for the additional dilution steps in the quantification and multiplied the corresponding values with the dilution factor relative to the starting dilution of 1:20. Finally, the result was the median of all valid dilution-corrected inhibition values for each variant.

Supplemental Figure 1 provides a schematic overview of the described calculations.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed, and figures were created with R version 4.2.0. Correlations between NT titer and sVNT results for all tested virus variants were calculated and reported as Spearman’s r (WT, Delta, BA.1, BA.2, BA.5). Cross-neutralizing activity was assessed by calculating the ratio of the WT neutralizing activity (log2 of the NT titer or sVNT result) to the variant-specific (Delta, BA.1, BA.2, BA.5) NT titer or sVNT result (also log2 transformed) for each variant and each cohort. Therefore, NT-ratios or sVNT-ratios close to one represent strong cross-neutralization, whereas a value between zero and one represents the dominance of the WT activity over the variant-neutralizing activity. Finally, NT-ratios for each variant were compared between the cohorts using pairwise Wilcoxon ranked tests (multiplicity-adjusted for the cohorts using the Bonferroni-Holm method). Alpha was set to 0.05. Possible sVNT cut-off values that represent a positive NT titer (≥ 10) were calculated by ROC analysis and Youden’s index for each variant.

To account for different sensitivities of the variant-specific RBDs contained in the assay, we additionally calculated linear regressions of the log2-transformed sVNT and NT results for each variant, thereby obtaining five linear models representing the relation between the two assays (log2(NT) = β * log2(sVNT) + intercept). The regression coefficients (β and intercept) were recorded for all variants, and the sVNT values were transformed by inserting them into the respective formulas. This process aimed to account for variant-specific differences in sensitivity in the sVNT by providing adjustment factors for future studies. Adjusted data was only included in the supplementary material.

Results

Correlation of the multivariant sVNT with variant-specific live-virus NTs

In this study, we analyzed whether differences in the variant-specific neutralizing activity of antibodies induced by different vaccination regimes (mono- and bivalent SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccinations) could be assessed with a dilution-corrected multivariant sVNT similar to live-virus NTs.

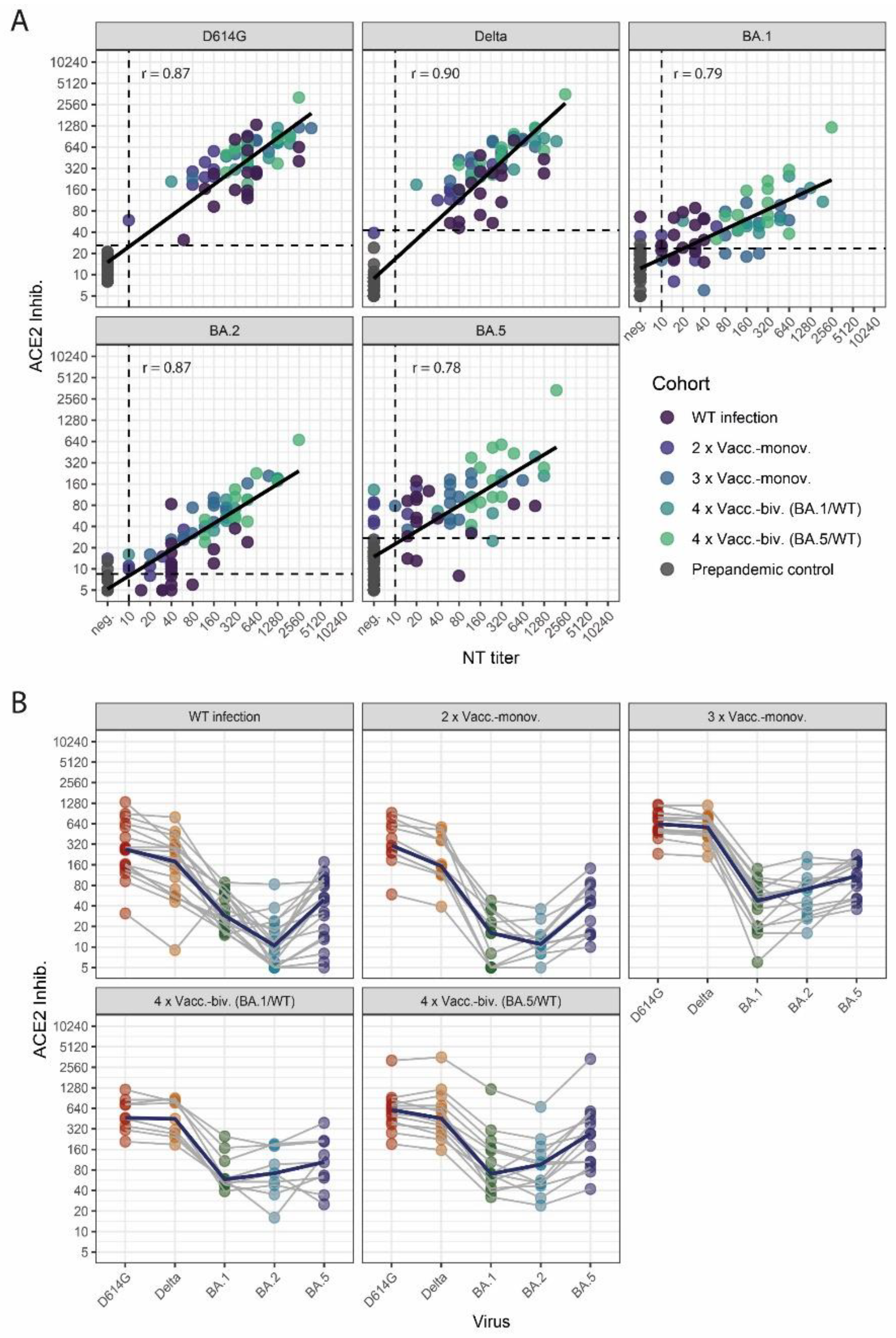

Therefore, we first analyzed the correlation of variant-specific sVNT values to the respective NT titers assessed by live-virus NTs (

Figure 1A). We observed a robust correlation for all SARS-CoV-2 variants, with a higher correlation for WT-, Delta-, and BA.2-specific neutralization than for Omicron BA.1 and BA.5 (Spearman: WT r = 0.87, Delta r = 0.90, BA.1 r = 0.79, BA.2 r = 0.87 and BA.5 r = 0.78). Then, we calculated cut-off values for the sVNT that correspond to positive NT titers (≥ 10) against the respective variants (

Figure 1A,

Supplementary Table S1).

Profiles of neutralizing activity after SARS-CoV-2 wild-type infection and vaccinations

Next, we analyzed neutralization profiles for the cohorts of WT-infected and vaccinated individuals (

Figure 1B). The cohorts of WT-infected individuals and two-times vaccinated subjects showed moderate WT- and Delta-specific and weak Omicron-specific neutralizing activity. In contrast, higher levels of nAbs and a less pronounced difference between WT- and Omicron-specific neutralizing activities were observed for three-times vaccinated individuals and individuals who received a bivalent (WT/BA.1 or WT/BA.5) booster (fourth dose) vaccination.

Notably, BA.5-specific RBD-ACE2-binding inhibition, as assessed by the sVNT, was higher in all cohorts than for BA.2 and BA.1. Since this over-representation of BA.5-specific neutralization was probably test-inherent, we calculated linear regressions between the NT titer and sVNT results to provide adjustment factors to correct for these sensitivity differences among the Omicron subvariants (

Supplementary Table S3),

Supplementary Figure S2 shows the neutralization profiles after adjustments).

Effect of mono- and bivalent booster vaccinations on the neutralizing activity

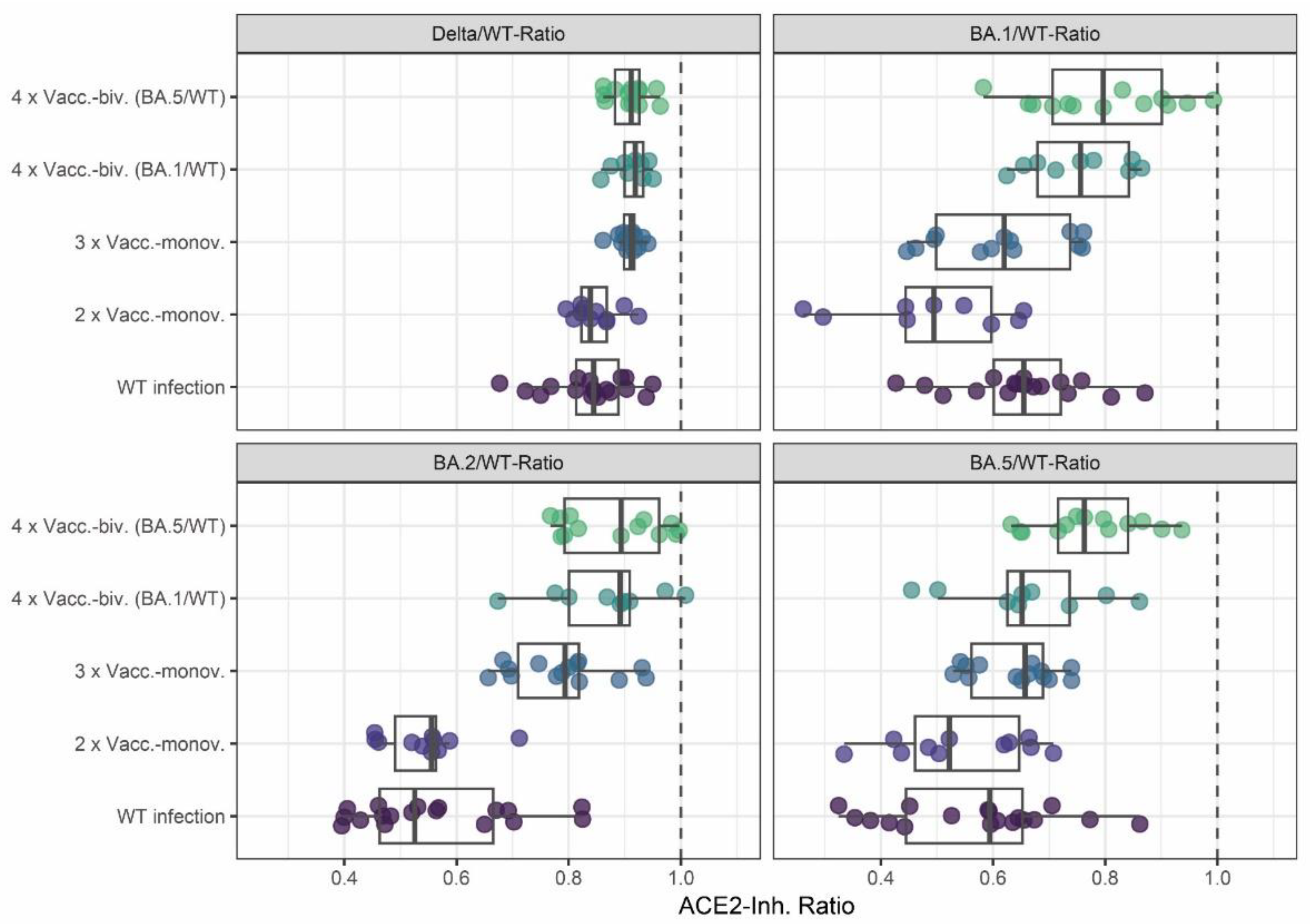

Finally, we analyzed the effect of monovalent versus bivalent booster vaccinations on the breadth of the neutralizing activity. To this end, we calculated the ratios of Delta, BA.1, BA.2, and BA.5 to WT surrogate neutralization results respectively. As shown in

Figure 2, variant cross-neutralization (as expressed by ratios closer to one) was increased after the third monovalent vaccination compared to only two-times vaccinated or WT-infected individuals. Indeed, the three-times vaccinated individuals had significantly higher Omicron BA.2 and BA.5 neutralizing activities than those after two vaccinations, with median ratios closer to one (for p-values, see

Supplementary Table S5).

A further increase in neutralization breadth was observed in individuals with a bivalent vaccination compared to those with monovalent vaccinations (

Figure 2). Notably, the bivalent BA.5/WT-vaccinated individuals had significantly higher Omicron BA.1 and BA.5 cross-neutralizing activity than all other cohorts except the bivalent WT/BA.1-vaccinated individuals who exhibited higher Delta and BA.2 cross-neutralization than the two-times vaccinated and wild-type infected cohorts. Similarly, the BA.1/WT bivalent vaccinated cohort displayed more Delta and BA.2 cross-neutralization than the WT infected and two-times vaccinated individuals, as well as more BA.1 cross-neutralization than the two- or three-times monovalent vaccinated cohorts.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated whether a novel multivariant sVNT that is based on a commercial microarray and quantifies the antibody-mediated inhibition of binding between ACE2 and variant-specific RBD proteins can identify differences in the cross-neutralization after monovalent versus bivalent booster vaccinations similarly to variant-specific live-virus NTs.

Indeed, in earlier studies that used live-virus NTs, individuals vaccinated three times with monovalent mRNA WT vaccines showed a significantly broader neutralizing activity than WT-infected or twice-vaccinated subjects [

16,

17]. However, a further improvement in cross-neutralizing activity was not found after a fourth monovalent wild-type vaccine dose [

18]. Hence, bivalent vaccines containing mRNA encoding both the SARS-CoV-2 WT, and Omicron BA.1 or BA.5, have been developed to increase the (cross)-neutralizing antibody activity against circulating and possibly future variants [

19].

Thus, measuring cross-neutralizing antibody profiles after bivalent booster vaccinations may be essential, e.g., for vaccine efficacy studies and routine diagnostics. However, this is limited by the laborious setup of performing multiple different variant-specific live-virus NTs with the same samples (e.g. [

7,

12,

13]). Using this labor-intensive approach, our group previously reported that bivalent vaccination moderately increased neutralizing activity against the respective Omicron variant applied with the vaccine [

7].

In the present study, we used the multivariant sVNT and similarly demonstrated that the bivalent BA.1/WT boosted cohort displayed increased cross-neutralization of BA.1 compared to the individuals three times vaccinated with monovalent vaccines. Also, similar to the live-virus NTs, individuals vaccinated with BA.5/WT adapted vaccines showed an increased cross-neutralization of both BA.1 and BA.5. Yet, in both bivalent vaccinated cohorts, wild-type titers were generally higher than Omicron titers, which has been attributed to immune imprinting to WT [

20].

Wild-type infected and twice vaccinated individuals, showed similar cross-neutralization (Fig. 2, refs?). Unexpectedly, the sVNT detected stronger cross-neutralization against BA.1 in the WT-infected cohort than in individuals vaccinated twice, but this may be related to the large number of individuals with low nAb levels against BA.1 in the latter cohort. Test-inherent differences in the sensitivity of detecting nABs against different Omicron subvariants by the sVNT might also contribute to this difference we observed.

If antibody neutralization against different Omicron subvariants is not assessed with a similar sensitivity by the sVNT microarray (e.g., due to differences in the concentration or conformation of the RBDs), this might pose a limitation, complicating a comparison of quantitive test results by the sVNT with respective NT titers. Therefore, we calculated linear regression models to compensate for test-inherent sensitivities and to improve the relationship between the live-virus NT titers and the quantitive results by the sVNT. The identified regression coefficients were used as adjustment factors by inserting the sVNT results in the regression models. As expected, the adjusted neutralization profiles more closely resembled the live-virus neutralization profiles reported in previous studies [

7,

12,

13].

Overall, the sVNTs gave very similar results to the live-virus NTs, which enables an analysis of cross-neutralizing antibodies against different SARS-Cov-2 variants in seroprevalence studies involving large parts of the population. Indeed, due to individual vaccination and infection histories, the profiles of nAbs against different variants and Omicron subvariants in the population will be highly heterogeneous, as has been demonstrated by Zaballa and colleagues [

8].

For this reason, future studies investigating the benefits of adapting COVID-19 vaccines to newly circulating strains (such as XBB) might measure antibody profiles in large study cohorts using sVNTs that allow a higher and faster turnover than live-virus NTs.

Thus, our data evaluating an sVNT microarray, including multiple dilution steps to identify optimal cut-offs with variant-specific live-virus NTs as the reference, may be relevant for applying such immunoassays in vaccine efficacy studies. Indeed, we demonstrate a proof-of-principle that not only variant-specific live-virus NTs but also multivariant sVNTs can identify the beneficial effect of Omicron-adapted vaccines on the breadth of neutralizing antibodies against different SARS-CoV-2 variants in the future.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to the study, have approved the submitted version of the manuscript, and agree to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and for ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work. Conceptualization, DNS, LW; Methodology, DNS, KP, KS; Software, DNS; Validation, DNS, KP, KS; Formal Analysis, DNS, LW; Investigation, DNS, EH, KP, KS, LW; Resources, EH, EP; Data Curation, DNS, KP; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, DNS, LW; Writing – Review & Editing, DNS, JHA, KS, LW; Visualization, DNS; Supervision, LW; Project Administration, LW; Funding Acquisition: LW.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and following national legislation and institutional requirements. The study was approved by the local ethics committee of the Medical University of Vienna, Austria (EK 1035/2016, EK 1513/2016, EK 1926/2020, EK 1291/2021). All samples were stored in the biobank according to established protocols approved by the local ethics committee.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants consented to antibody testing at the Center for Virology. As the study used only anonymized residual material from routine diagnostics, the ethics committee waived the necessity for written consent.

Data Availability Statement

Data from this study has not been publicly archived.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jutta Hutecek, Christina Tratberger, and Elke Peil for their excellent technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

ACE2: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor, ACE2-Inhib.: ACE2-RBD inhibition, AP: alkaline phosphatase, Biv.: bivalent, CPE: cytopathic effect, ECACC: European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures, mono: monovalent, NT: Neutralization test, PCR: polymerase chain reaction, SARS-CoV-2: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, sVNT: surrogate virus neutralization test, TCID50: tissue culture infection dose 50, RBD: receptor-binding domain, Vacc.: Vaccinated, WT: wild-type, y: year.

References

- Hachmann, N.P.; Miller, J.; Collier, A.Y.; Ventura, J.D.; Yu, J.; Rowe, M.; Bondzie, E.A.; Powers, O.; Surve, N.; Hall, K.; et al. Neutralization Escape by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4, and BA.5. The New England journal of medicine 2022, 387, 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medits, I.; Springer, D.N.; Graninger, M.; Camp, J.V.; Höltl, E.; Aberle, S.W.; Traugott, M.T.; Hoepler, W.; Deutsch, J.; Lammel, O.; et al. Different Neutralization Profiles After Primary SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 Infections. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 946318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rössler, A.; Netzl, A.; Knabl, L.; Schäfer, H.; Wilks, S.H.; Bante, D.; Falkensammer, B.; Borena, W.; von Laer, D.; Smith, D.J.; et al. BA.2 and BA.5 omicron differ immunologically from both BA.1 omicron and pre-omicron variants. Nature communications 2022, 13, 7701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dejnirattisai, W.; Huo, J.; Zhou, D.; Zahradník, J.; Supasa, P.; Liu, C.; Duyvesteyn, H.M.E.; Ginn, H.M.; Mentzer, A.J.; Tuekprakhon, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron-B.1.1.529 leads to widespread escape from neutralizing antibody responses. Cell 2022, 185, 467–484.e415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springer, D.N.; Perkmann, T.; Jani, C.M.; Mucher, P.; Prüger, K.; Marculescu, R.; Reuberger, E.; Camp, J.V.; Graninger, M.; Borsodi, C.; et al. Reduced Sensitivity of Commercial Spike-Specific Antibody Assays after Primary Infection with the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant. Microbiology spectrum 2022, e0212922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Yisimayi, A.; Jian, F.; Song, W.; Xiao, T.; Wang, L.; Du, S.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Chen, X.; et al. BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5 escape antibodies elicited by Omicron infection. Nature 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springer, D.N.; Bauer, M.; Medits, I.; Camp, J.V.; Aberle, S.W.; Burtscher, C.; Höltl, E.; Weseslindtner, L.; Stiasny, K.; Aberle, J.H. Bivalent COVID-19 mRNA booster vaccination (BA.1 or BA.4/BA.5) increases neutralization of matched Omicron variants. NPJ Vaccines 2023, 8, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaballa, M.E.; Perez-Saez, J.; de Mestral, C.; Pullen, N.; Lamour, J.; Turelli, P.; Raclot, C.; Baysson, H.; Pennacchio, F.; Villers, J.; et al. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and cross-variant neutralization capacity after the Omicron BA.2 wave in Geneva, Switzerland: a population-based study. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2023, 24, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springer, D.N.; Traugott, M.; Reuberger, E.; Kothbauer, K.B.; Borsodi, C.; Nägeli, M.; Oelschlägel, T.; Kelani, H.; Lammel, O.; Deutsch, J.; et al. A Multivariant Surrogate Neutralization Assay Identifies Variant-Specific Neutralizing Antibody Profiles in Primary SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Infection. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos da Silva, E.; Servais, J.Y.; Kohnen, M.; Arendt, V.; Staub, T.; The Con-Vince, C.; The CoVaLux, C.; Krüger, R.; Fagherazzi, G.; Wilmes, P.; et al. Validation of a SARS-CoV-2 Surrogate Neutralization Test Detecting Neutralizing Antibodies against the Major Variants of Concern. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graninger, M.; Jani, C.M.; Reuberger, E.; Prüger, K.; Gaspar, P.; Springer, D.N.; Borsodi, C.; Weidner, L.; Rabady, S.; Puchhammer-Stöckl, E.; et al. Comprehensive Comparison of Seven SARS-CoV-2-Specific Surrogate Virus Neutralization and Anti-Spike IgG Antibody Assays Using a Live-Virus Neutralization Assay as a Reference. Microbiology spectrum 2023, e0231422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, A.Y.; Miller, J.; Hachmann, N.P.; McMahan, K.; Liu, J.; Bondzie, E.A.; Gallup, L.; Rowe, M.; Schonberg, E.; Thai, S.; et al. Immunogenicity of BA.5 Bivalent mRNA Vaccine Boosters. The New England journal of medicine 2023, 388, 565–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalkias, S.; Harper, C.; Vrbicky, K.; Walsh, S.R.; Essink, B.; Brosz, A.; McGhee, N.; Tomassini, J.E.; Chen, X.; Chang, Y.; et al. A Bivalent Omicron-Containing Booster Vaccine against Covid-19. The New England journal of medicine 2022, 387, 1279–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koblischke, M.; Traugott, M.T.; Medits, I.; Spitzer, F.S.; Zoufaly, A.; Weseslindtner, L.; Simonitsch, C.; Seitz, T.; Hoepler, W.; Puchhammer-Stöckl, E.; et al. Dynamics of CD4 T Cell and Antibody Responses in COVID-19 Patients With Different Disease Severity. Frontiers in medicine 2020, 7, 592629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graninger, M.; Camp, J.V.; Aberle, S.W.; Traugott, M.T.; Hoepler, W.; Puchhammer-Stöckl, E.; Weseslindtner, L.; Zoufaly, A.; Aberle, J.H.; Stiasny, K. Heterogeneous SARS-CoV-2-Neutralizing Activities After Infection and Vaccination. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 888794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruell, H.; Vanshylla, K.; Tober-Lau, P.; Hillus, D.; Schommers, P.; Lehmann, C.; Kurth, F.; Sander, L.E.; Klein, F. mRNA booster immunization elicits potent neutralizing serum activity against the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Nat Med 2022, 28, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandt, J.; Muik, A.; Salisch, N.; Lui, B.G.; Lutz, S.; Krüger, K.; Wallisch, A.K.; Adams-Quack, P.; Bacher, M.; Finlayson, A.; et al. Omicron BA.1 breakthrough infection drives cross-variant neutralization and memory B cell formation against conserved epitopes. Sci Immunol 2022, 7, eabq2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Zou, J.; Kurhade, C.; Liu, M.; Ren, P.; Pei-Yong, S. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sublineages by 4 doses of the original mRNA vaccine. Cell Rep 2022, 41, 111729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krammer, F.; Ellebedy, A.H. Variant-adapted COVID-19 booster vaccines. Science 2023, 382, 157–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreño, J.M.; Singh, G.; Simon, V.; Krammer, F. Bivalent COVID-19 booster vaccines and the absence of BA.5-specific antibodies. The Lancet. Microbe 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).