1. Introduction

Vegetable oil crops are second only to cereals in their importance for human nutrition and wellbeing. Oil-rich seeds and fruits were collected by human hunter-gatherers as foods and for other purposes for over 100,000 years (Marquer et al, 2022). Oil-rich plants were also some of the earliest crops selected for domestication by the first farmers. Examples include sesame and olive, which were widely cultivated and traded across the Levant over 6,000 years ago, and oil palm, which was grown in West Africa over 5,000 years ago and from where some of the oil was transported 3,000 km for use in ancient Egypt (Murphy, 2008). Liquid oils (mainly from plants) and solid fats (mainly from animals) typically make up 25-35% of adult daily energy needs. They also supply key nutrients, such as essential fatty acids, the lipidic vitamins A, D and E, as well as important flavour compounds that enhance the taste, odour and digestibility of many foods. In addition to their vital roles in human and livestock nutrition, about a quarter of global vegetable oil output is used for a wide range of industrial purposes.

Historically, many human diets were deficient in fats and, despite their increasing availability, even today about 800 million people (10% of the global population) have suboptimal intakes of fat for their daily needs. One remarkable aspect of oil crop production is its dramatic 900% increase from 26 Mt to 238 Mt in the 60 years between 1961 and 2021, during a period when cereal crops only increased by 10% and the human population only increased by 270% (FAOSTAT, 2025; Meijaard et al, 2024). In contrast, over the same period, per capita consumption of animal fats has remained constant, although there are indications that it is now decreasing in some richer countries (Micha et al, 2014). The increase in vegetable oil production, particularly palm oil, has helped reduce undernutrition in lower-income countries in Asia (FAO, 2021; Sanders, 2024). While 72% of global vegetable oil production is used for human consumption, these versatile crops also supply a wide range of renewable biofuels, as well as animal feed and oleochemicals (IUCN, 2024).

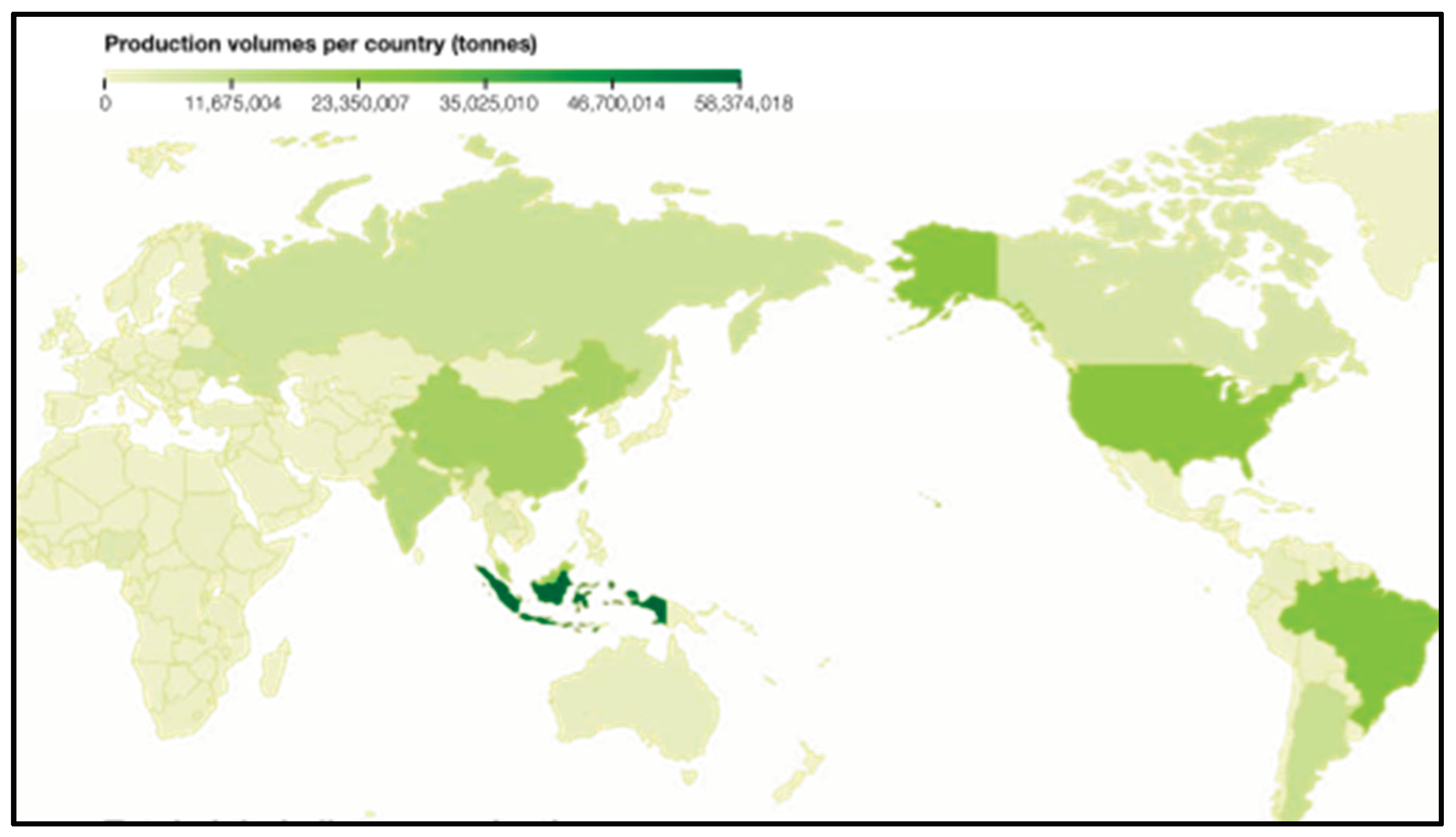

Today, vegetable oil crops and their derivatives are among the most traded agricultural commodities, with 56% of the oils entering international supply chains, many of which span several continents (Poore & Nemecek, 2018). As shown in

Figure 1, these crops are grown worldwide and currently occupy 540 Mha, which is

~37% of all agricultural land with an annual production value of >$265 billion. Due to factors such as population increase, improved economic conditions, and demand for biofuels, there is continued upward pressure on land use for oil crops, with estimates of a further 14% production increase required by 2050 (IUCN, 2024). Such an increase would require an additional 35 Mt oil and the conversion of an extra 10-40 Mha of already-scarce cropland. A significant confounding factor that is becoming increasingly evident is that a combination of climate-related events (including pest/disease outbreaks), sustainability concerns, and geopolitical uncertainties are already threating existing vegetable oil

supply chains, even without considering the likely additional production required over the coming decades (Ritchie, 2024; FAOSTAT, 2025; Syahid et al, 2025

).

The global vegetable oil crop sector contributes to most of the 14 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in particular zero-hunger, good-health & well-being, and responsible consumption & production (UN, 2022; Murphy, 2024a). While it is clear that vegetable oil crops continue to be essential for food and non-food uses and that significant increases in their global production will be required, there is also a growing realisation that this could come at a considerable cost in terms of land use and optimal sustainability strategies. Similar concerns have been levelled at other aspects of crop production and especially at the economic and environmental efficiency of different types of cropping regimes. For example there is a growing realisation that new policies are required to utilise the largely untapped potential of many perennial woody crops in addressing sustainable development in many parts of the world (Martinez-Nuñez et al, 2024).

Currently, annual crops make up about 75% of global cropland and edible calorie production (Lobell, 2011), but their usefulness is limited by relatively low rates of carbon sequestration compared to perennial crops, especially in the tropics (Murphy, 2025). For example, agricultural soils in Europe are estimated to sequester an annual <16–19 Mt C, which is less than one fifth of the theoretical potential and equivalent to only 2% of European anthropogenic emissions (Freibauer et al, 2004). Among the ameliorative measures proposed in the study were the introduction of perennial crops, zero tillage, organic inputs, and raising the water table in arable peatland. However, the vast majority of the three major annual vegetable oil crops are grown in highly mechanised but relatively low-yielding industrial monoculture systems with high input requirements that include fertilisers, biocides, and fossil-derived diesel fuel, all of which carry considerable amounts of embedded GHG emissions.

In contrast, while perennial crops are less commonly cultivated than annual crops, they have much greater potential in terms of future food

security and environmental sustainability (Cox et al, 2006; Dawson, 2022). Perennial crops include many tree species that provide effective and diverse wildlife habitats, extensive rhizosphere-friendly rooting systems that are not disrupted by annual replanting, and greatly improved rates of carbon sequestration and storage (

Kantar et al, 2016; Kreitzman et al, 2020; Sprunger et al, 2020; Chapman, 2022; Meijaard et al, 2024). Perennial oil crops in particular also lend themselves to cultivation via agroforestry, either using shade trees during the first few years of growth or in mixed stands throughout their productive lives. Examples that have been recently reviewed include oil palm, olive, cocoa, and coconut (Murphy, 2025; Rahmani et al, 2012; Rival et al, 2025). It was also reported that

the growing areas of soybean, rapeseed, sunflower are associated with the globally most threatened terrestrial ecosystems while coconut and oil palm are grown in areas that are less critically threatened, (Meijaard et al, 2021; 2024

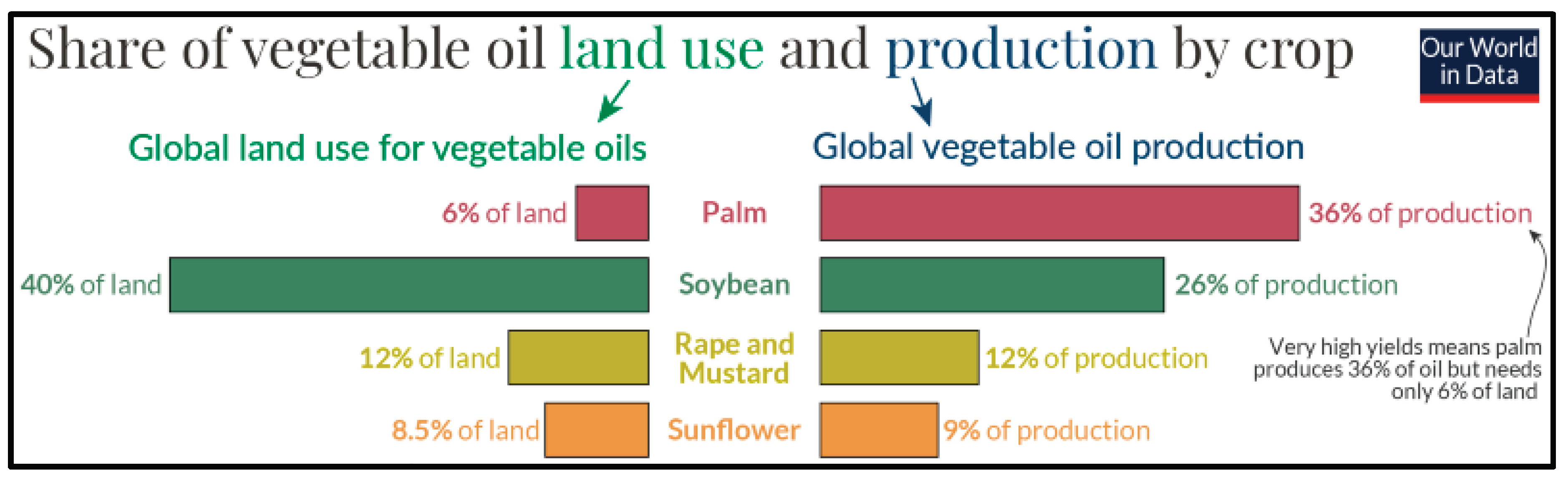

). The dichotomy between land-sparing perennial oil palm and the three land-hungry annual oilseed crops is shown in

Figure 2.

One way in which tropical oil crops can address the current environmental crisis is by more effectively sequestering CO2 from the atmosphere which, as we will see below, is something that is not possible with annual oil crops. This is an urgent priority because the global carbon cycle has become dangerously unbalanced over the past 70 years due to the rapid and uncontrolled release of CO2 from the use of fossil fuels (Murphy, 2020b; 2024c). This is shown quantitatively by data from the Salk Institute, USA that reveal a global annual sequestration via photosynthesis of 677 Gt CO2 (Salk Institute, 2025). Of this total, about 660 Gt CO2 is re-released to the atmosphere via respiration by plants and animals, meaning that in a fully balanced cycle there would be a modest net annual CO2 sequestration of 17 Gt. Unfortunately, however, anthropogenic CO2 release, mainly from fossil fuels, emits a further 34 Gt into the atmosphere, meaning that instead of a modest annual CO2 sequestration there is an ever-increasing net CO2 emission rate of 16.3 Gt/yr. This net release of CO2 into the atmosphere has driven its inexorable rise over recent decades from 300 ppm in 1950 to 429 ppm by 2025, and is regarded as a major contributor to global climate change (Murphy, 2024c; 2025).

Recent research has highlighted the carbon sequestration potential of terrestrial vegetation as a way of restoring the global carbon cycle alongside the ongoing efforts to reduce anthropogenic emissions (Lal et al, 2018; Mo et al, 2023; Murphy, 2025). This concept has been termed ‘recarbonization of the terrestrial biosphere’ and croplands with high carbon sequestration potential are important components of the strategy. Such measures have an estimated capacity of 367 Gt C capture by the end of the 21st century, which could reduce atmospheric CO2 levels by 156 ppm (Lal et al, 2018). To put this into context, atmospheric CO2 levels remained below 300 ppm throughout human history until the anthropogenic releases after the mid-20th century resulted in an unprecedented rise to 429 ppm in 2025 (Murphy, 2025). A global audit of natural forests concluded that there is a huge untapped potential to increase carbon sequestration via improved forest management that could capture as much as 139 Gt C (Mo et al, 2023). Similarly, the optimisation of land management, including cropland, could enable the sequestration of an additional 13.7 Gt C/yr (Sha et al, 2022). Finally, the extension of tree planting in non-forest landscapes has been shown to contribute to human wellbeing (Choksi et al, 2025).

In this study, the four principal global vegetable oil crops, oil palm, soybean, rapeseed and sunflower, were compared with respect to their contrasting cultivation methods/locations, economic yields, carbon emission/uptake dynamics and related sustainability criteria. It is concluded that, while all four crops provide useful production systems for vegetable oils, there are clear benefits from focusing more on perennial oil palm as a uniquely high-yielding, land-sparing crop where ongoing environmental and yield improvements make it an ideal choice as the premier food and non-food producer as the world faces an increasingly uncertain future.

2. Oil Palm

The African oil palm,

Elaeis guineensis, is quantitatively the most important vegetable oil crop; its 90 Mt/yr oil production comprises 40% of the global market and is worth an annual

$77 billion. Two oils are produced, mesocarp oil comprising 90% and kernel oil, comprising 10% of total. The crop is grown between latitudes 10

o N to 10

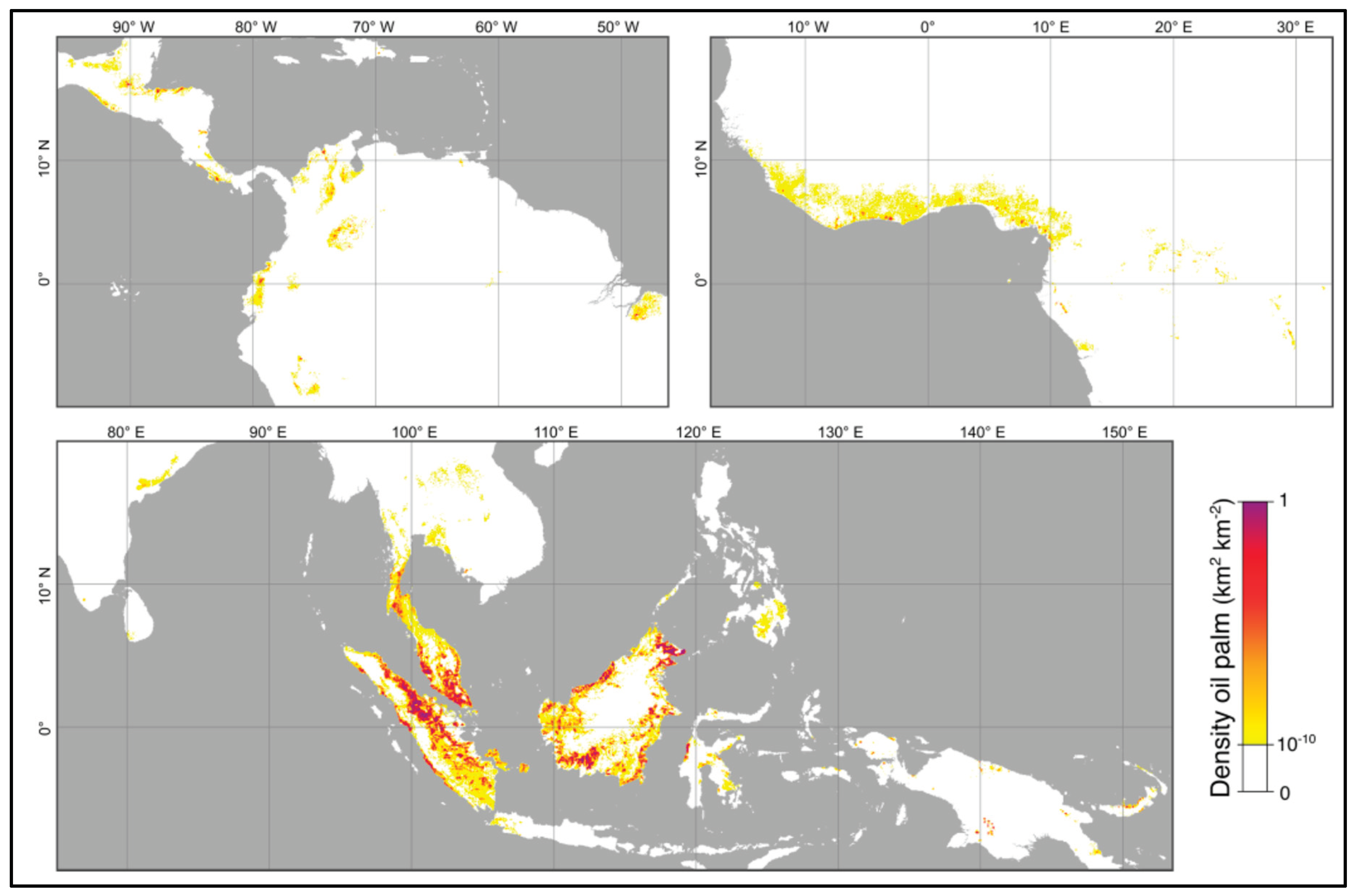

o S across the humid tropics of Asia, Africa and Central/South America (Feintrenie et al, 2025). However, 85% of global production is concentrated in just two countries, namely Indonesia and Malaysia, as shown in

Figure 3.

Unlike soybean plants, which typically reach a height of only ~60 cm, commercial oil palms grow as tall perennial trees that can reach over 10 metres in height and are able to store an annual 2.5 t/ha carbon during their productive lifetime of about 20 to 25 years. This primary productivity is comparable to and can even sometimes exceed that of some tropical forests (Henson, 1999a; 1999b; 2017; Lamade & Bouillet, 2005; Sheil et al, 2009; Henson et al, 2012a; 2012b; Pulhin et al, 2014; Cheah et al, 2015; Daud et al, 2019; Uning et al, 2020; PAPSI-Monitor, 2021; Alcock et al, 2022; Murphy, 2004b; Murphy et al, 2005).

The carbon sequestration capacity of oil palm crops to produce vegetable oil is at least five-times more efficient in terms of land use than that of the three major annual oil crops (Corley & Tinker, 2015; Sibhatu, 2023; Murphy, 2024b). The impressive photosynthetic capacity of oil palm is readily apparent from simply looking at a plantation with its luxuriant foliage and plentiful woody biomass that grows year-round for 25-30 years yielding an annual 3-4 t/ha oil. In contrast, the annual oil crops consist of tenfold shorter leafy, non-woody plants that only grow for about four months/yr, and require replanting ever year, while only yielding about 0.4-1.5 t/ha oil. Several studies have reported oil palm net CO2 assimilation rates that can be comparable to some tropical forests (Henson, 1999a; 1999b; 2017; Lamade & Bouillet, 2005; Sheil et al, 2009; Henson et al, 2012a; 2012b; Pulhin et al, 2014; Cheah et al, 2015; Daud et al, 2019; Uning et al, 2020; PAPSI-Monitor, 2021; Alcock et al, 2022).

In addition to carbon stored in the trees themselves, oil palm plantations are highly efficient at storing sequestered organic carbon in the soil, where a Mexican study found most accumulation under frond areas and the wider palm circle (Brindis-Santos et al, 2021). In the soil, the estimated carbon storage was 87 t C /ha and 67 t C /ha at depths of 20 and 60 cm, respectively. Regarding land-use comparison, results indicate a small increase in carbon storage to 27% at 20 cm depth and 18% at 60 cm when comparing pastureland with oil palm plantations. However, secondary-growth forest had a higher carbon storage compared to both other land uses (Borchard et al, 2019). Soil organic carbon (SOC) was also higher by 16–27% in oil palm plantations than in pastureland, which was similar to data from grassland to oil palm in 6-, 9-, 12- and 25-year old plantations in Indonesia (Goodrick et al, 2015). The incorporation of fallen biomass from oil palm plants therefore acts as an organic input providing favourable conditions for soil health, which was evidenced by the increased amount of SOC in the management areas receiving the largest quantities of organic residues under plants. As noted by Trenberth & Smith (2005), the stock of SOC in the terrestrial biosphere is linked with overall atmospheric CO2 concentrations. Subsoil layers at >30 cm depth are an important reservoir of long-term sequestered carbon that can be thousands of years old (Button et al, 2022). The composition and age of subsoils in oil palm plantations has been little studied and could represent a hitherto unrecognised element in their capacity to store carbon.

Similarly to soybean, the impact of historical oil palm expansion on carbon emissions has received considerable attention, although there has been a tendency in some quarters to ignore or downplay more recent positive developments. A particularly contentious issue had been the use of tropical peatland, especially deep-peat soils, for conversion to oil palm plantations. The clearance of forests and drainage of peatlands for oil palm emits substantial carbon dioxide (Wijedasa et al, 2016), and generates local climate change (McAlpine et al, 2018). However, considerable progress has been made in addressing the peat issue in recent years. For example, by rewetting drained peatlands on oil palm plantations in West Kalimantan, Borneo where it has been claimed that this could reduce CO2 emissions by as much as 3.9 Mt/yr (Parish, 2023; Novita et al, 2024). Recent mapping data also show that across all regions of Indonesia oil palm planting peaked from 2009-2012 and has subsequently declined 8-fold, while the proportion of peatland was never more than 21% of the converted crop area and is now reduced to 7% (Nusantara Atlas (2025). This underscores the need to contextualise the peat issue as being historically constrained and not applying to oil palm cultivation as a whole.

Oil palms can maintain high rates of carbon uptake and their oil can be converted to biodiesel and used to substitute for fossil fuels (Quezada et al, 2019). However, in terms of carbon balance, oil palm biodiesel cannot offset the carbon released in the case of forests peatlands drained over short or medium timescales (Searchinger et al, 2018). Moreover, the carbon opportunity cost of oil palm, which reflects the ability of the land to store carbon if it is not used for agriculture, does not differ significantly from annual vegetable oil crops (Searchinger et al, 2018). Clearly oil palm production systems are much more complex than those of the annual oil crops, but there are many field studies up to plantation level that investigate strategies for biodiversity enhancement, including linking cropping areas with natural forests via corridors for both plants and animals (Woodham et al, 2019; Luke et al, 2020). Even within large commercial plantations, which can extend over many hundreds of hectares, floral islands consisting of natural vegetation can be created (Masure et al, 2023; Zemp et al, 2023).

There are many ways in which both the existing yield performance and environmental impacts of oil palm cultivation can be considerably improved so that this already immensely productive crop can be made an even more effective way of addressing future needs for renewable oil supplies. For example, further cropland expansion can be minimised by increasing the already high oil yield by replanting with existing superior genotypes, avoiding all use of peatland and other sensitive natural biomes, by improving the management of existing plantations, and by modernising the operation of mills and refineries to include the capture of waste methane and its use for power generation (Murphy et al, 2021, Murphy, 2024b; Shehu, 2025). Among all the major oil crops, oil palm requires the least amount of fertiliser to produce a tonne of oil while the fertiliser efficiency for other oil crops varies according to specific crop requirements and agronomic practices (Viglione, 2022).

As noted below in more detail, annual crops such as rapeseed and sunflower are already experiencing adverse effects of climate change (Chain Action Research, 2018; World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), 2023; Qian et al, 2018; Pullens et al, 2019; Debaeke et al, 2017; Murphy, 2024a). In the case of oil palm the situation is less clear, although long-term scenarios based on initial modelling approaches are pessimistic (Paterson, 2020; 2021). More recently, the use of remote sensing has enabled a more precise evaluation of the spatiotemporal variation of oil palm yields in Indonesia and Malaysia (Syahid et al, 2025). Data from the past two decades indicate that by far the greatest drivers of yield variation are climatic factors, with other drivers including management practices, climatic conditions, plant age, and the use of peatland (Syahid et al, 2025).

There are likely to be pressures to expand oil palm cultivation in the future and, while this is possible, it is important that it is not self-defeating in terms of replacing tropical forests that are already highly efficient carbon sequestration systems. One of the ‘new frontiers’ of oil palm cultivation is in South America where much of the expansion has been smallholder-driven conversion of non-forest land. Unfortunately some industrial-scale monocultures have also been planted on forest land (Masure et al, 2023) although this often carries a commensurate penalty in terms of lower rates of lower carbon sequestration (Hergoualc’h et al, 2025). The use of optical and radar imagery analysed with 95% accuracy by the Random Forest algorithm is now enabling a greater transparency in the use of remote sensing to determine the real extent of crop expansion, including oil palm, in the tropics. For example, between 2014 and 2020 the oil palm area in eastern Amazonia expanded by >72% to 0.18 Mha, although on the plus side, only 20% of this expansion was at the expense of natural vegetation (De Barros et al, 2025). Another interesting use of remote sensing has shown that there are extensive areas of hitherto unreported oil palm cultivation in Africa where as much as 6-7 Mha of this cryptic cropland is present adjacent to village smallholdings (Descals et al, 2025).

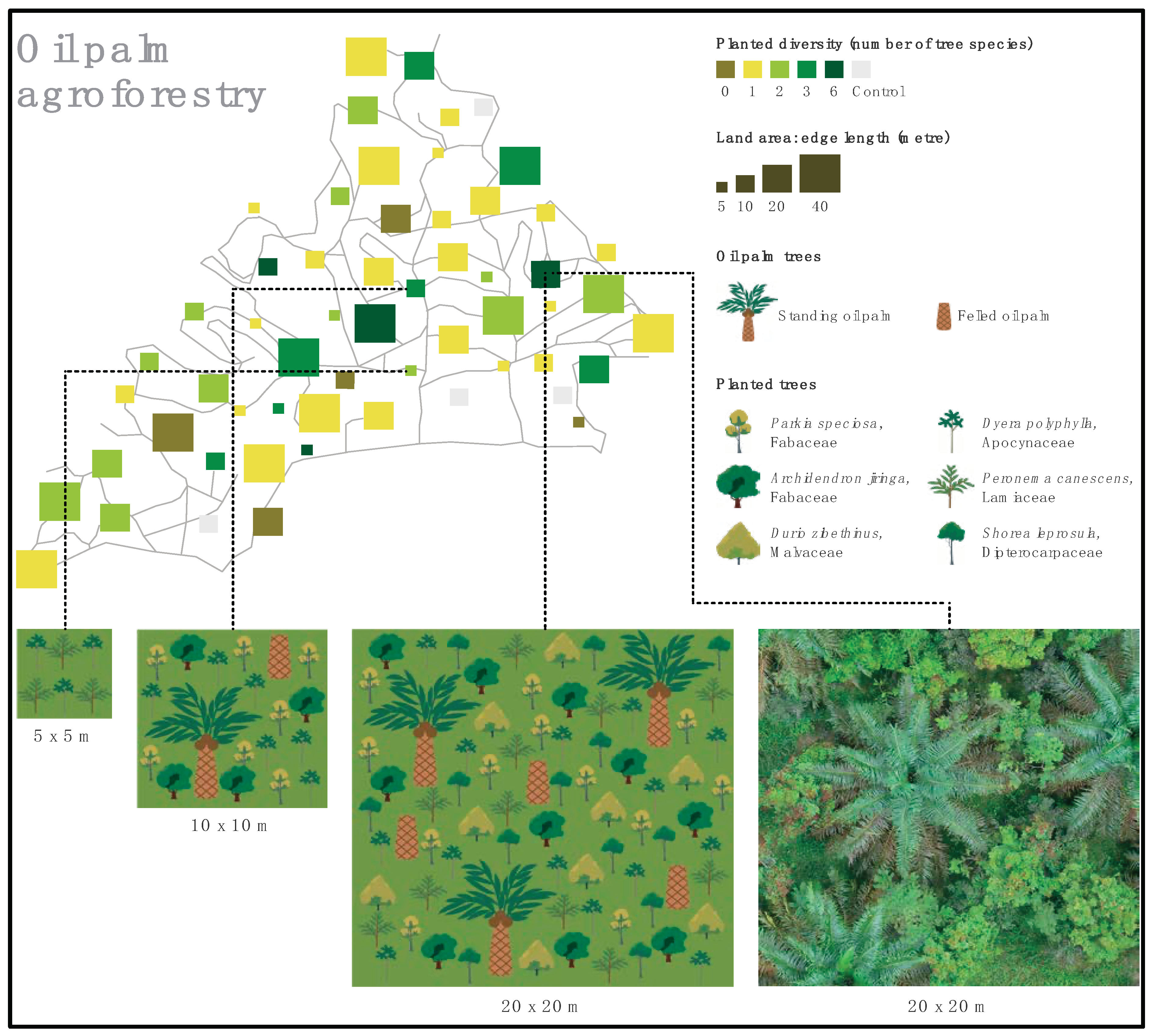

Another strategy to promote more effective carbon sequestration is to grow perennial tropical crops as part of agroforestry systems (Albrecht & Kandji, 2003; Kumar & Nair, 2011; Dhyani et al, 2020; Ghale et al, 2022; Messier et al, 2022). It was estimated that such agroforestry systems could sequester up to 0.23 Mt C/yr (Albrecht & Kandji, 2003). However, efforts to quantify the sequestration potential of agroforestry systems are notoriously difficult to achieve and some quoted values should be treated with caution (Kumar & Nair, 2011; Ghale et al, 2022). The two major cultivation techniques for oil palm crops, namely large-scale commercial plantations covering thousands of hectares versus family-run smallholder plots of a few hectares, are quite different in their suitability for agroforestry. In general smallholder plots are often already cultivated as part of a mixed-use system that can include other ground-cover and cash crops. One of the drawbacks for smallholders is that, despite their environmental advantages, agroforestry systems can be more difficult and risky to manage. Nevertheless, numerous recent studies have highlighted the benefits of agroforestry for oil palm smallholders across the world (Rahmani et al, 2021; Masure et al, 2023; Braga et al, 2024; Hendrawan & Musshoff, 2024).

In contrast, the vast majority of large-scale commercial plantations are currently run as monocultures, albeit with additional volunteer vegetation such as shade-tolerant species and the temporary use of leguminous ground cover during the first few years after planting. However, introduction of long-cycle food crops into newly established monocrop palm plantation has been associated with delayed production and a decrease in palm yields over the longer term (Rafflegeau et al, 2010; Koussihouèdé et al, 2020; Masure et al, 2023). Despite this, there is an increasing body of research into the potential of commercial oil palm cultivation to embrace agroforestry in some circumstances as part of a wider effort to increase the environmental credentials of the crop (Khasanah

et al. 2020; Ahirwal et al 2022; Deines, 2024). A recently reported option is to establish agroforestry schemes with species such as

Coffea liberica and

Shorea balangeran in threatened peatland ecosystems as a way of enhancing the carbon footprint and economic value while also limiting forest conversion (Frianto

et al, 2024). Another recent initiative is the TRAILS multidisciplinary approach involving mixed tree plantations, interplanted rows, and forest islands (Rival et al, 2025). The forest or tree island concept is shown schematically in

Figure 4.

As noted repeatedly in this report and elsewhere, one of the outstanding characteristics of oil palm crops is their high yield of oil per hectare, which greatly outstrips the yields of all other oil crops. However, there is a long-standing conundrum in the oil palm sector, namely the failure of oil yields to increase over time, despite advances in breeding and agronomy. Indeed, the stagnation in oil yields has more recently turned into a significant decline – a phenomenon that has been discussed by the author and other experts for over several decades (Henson, 2002; Murphy, 2009; 2014; USDA, 2012). This situation is in stark contrast with the annual oil crops, all of which have seen a doubling or even trebling of average oil yields over the past few decades (Chandran, 2019; Pilorgé et al, 2020; Our World in Data, 2025). As early as 2000-2002, the stagnation in oil yields in Malaysia was the subject of concern by several authors (Tinker, 2000; Pushparajah, 2001; Henson, 2002; Jalani et al, 2002). In 2002 it was concluded that Malaysian oil palm yields had been static since 1976, with an average of 3.63 t/ha (Henson, 2002). USDA data then showed a transient yield increase in the early 2000s but this was followed by a decline in the early 2010s (USDA, 2012). As recently as 2025, the ongoing yield decline was labelled as one of the ‘inconvenient truths’ (alongside lack of replanting, Ganoderma spread, labour issues, and mechanisation) that bedevil the industry (Lee, 2025).

Although oil yields vary considerably according to factors such as plantation age and efficiency of agronomic and management practices (Woittiez et al, 2017; Monzon et al, 2023), it is still surprising that the latest data from Statista shows a global average yield of only 3.3 t/ha, which is less that the average Malaysian yield of 3.63 t/ha from almost half a century ago. Even more puzzling is that, at the same time, some plantations report yields in the region of 6.3 t/ha in Malaysia and 5.4 t/ha in Indonesia (Salim, 2024). Also, Sime Darby (now called SD Guthrie) in 2020 announced new high-yield GenomeSelectTM breeding lines, with a claimed 9.9 t/ha average yield over 5 years in field trials under optimum conditions, that are scheduled for large-scale production in 2025 (Shankar, 2021; SD Guthrie, 2023). Estimates of the maximum yield potential in the literature vary significantly from 12 t/ha, as already achieved on a small scale, to 18.7 t/ha in simulation models (Woittiez et al, 2017). Further yield improvements could come from redesign of the crop architecture similarly to the breeding of semi-dwarf cereal crops that underpinned the ‘Green Revolution’ of the 1960s and 1970s (Murphy, 2008; Zubaidah & Said, 2022). Other examples of strategies for yield improvements by both smallholders and commercial growers include reducing the harvest cycle length from 19.6 to 8.3 days (Escallón-Barrios et al. 2020) and measures such as more effective weed management, pruning, nutrient application and using appropriate harvesting criteria such as the amount of loose fruits instead of bunch colour (Lee et al, 2014; Mohanaraj & Donough, 2016; Monzon et al, 2023) Innovative new ideas for ‘smart’ oil palm mills have also been advanced (Isaac, 2019) as well as the use of digital technologies, such as blockchain, to enhance the performance and transparency of supply chains (Keong, 2019).

Therefore there is a great deal of unrealised potential for significant increases in oil yields with a doubling to 6-7 t/ha already feasible simply by management improvements, and a possible trebling to 10 t/ha possible in the medium term using a combination of best practices and superior breeding lines. To summarise, oil palm crops produce an impressive 90 Mt/yr oil on a relatively low land area of 29 Mha. As a perennial tree species with a 25-30 yr growing cycle, it has a very high capacity to sequester atmospheric CO2 and, in addition to its oil-rich fruits, it produces large quantities of useful lignified biomass. A further benefit is that the crop is mostly rainfed and has relatively low fertiliser requirements.

3. Soybean

Soybean,

Glycine max, is the second most productive vegetable oil crop after oil palm. Its annual 68 Mt/yr oil yield on a land footprint of 130 Mha comprises 27.8% of the global oil market and is worth an annual

$78 billion. This annual crop is mainly grown in warm climates between latitudes 30

o N to 45

o S with three countries, Brazil, USA and Argentina, accounting for 80% of global production (see

Figure 5). The crop has a brief growing season of 120 days and reaches a mature height of only 0.6-1.0m. Although the oil is important, it only makes up 20% of seed weight and the main economic products of the annual 422 Mt of soybean production are the intact grain and the protein-rich meal, meaning that 80% of the crop is fed to livestock, especially beef and dairy cattle and poultry for meat, milk and egg production, plus a smaller amount used for foods such as tofu and soy milk (UFOP, 2021). The major centres of soybean oil consumption are China, USA and India where it is primarily used for human consumption with smaller amounts used for industrial purposes such as biodiesel and oleochemicals.

Its fatty acid composition is similar to the two other major annual oils, rapeseed and sunflower, albeit with high-oleic varieties increasingly being grown due to their superior nutritional and technical performances. For example, high-monounsaturate oils are widely marketed for healthy diets, in order to avoid trans-fats generated by hydrogenation, for increased stability for both domestic and commercial frying, and for their benefits when used in livestock feed (Baer et al, 2021; Hanno et al, 2024; Oviedo-Rondon, 2024). In recent years, high polyunsaturated oils, including most commodity varieties of soybean and sunflower, have lost an annual market share (totalling 4 Mt for soybean oil) in many edible sectors due to mandatory trans-fat labelling and avoidance of ω-6 linoleic acid (United Soybean Board, 2024). In some cases, such as solid fats, palm oils (olein and stearin fractions) have benefited as substitutes for soybean oil, but the rollout of high-oleic soybean varieties is now underway, although it is proceeding at a puzzlingly slow pace in the USA (United Soybean Board, 2024).

In recent years, soybean cultivation has come under increasing scrutiny due to its high land use and carbon footprints that have followed a tenfold production increase between 1961 and 2021, much of which was in Brazil (Ritchie, 2021). The role of this additional soybean cultivation in deforestation is much debated, but it is clearly a contributing factor, in tandem with land clearances for cattle pasture and small-scale farming, that contributes to increased forest loss in Brazil (Rudorff et al, 2011; Tyukavina et al, 2017; Soterroni et al, 2019; Kuschnig et al, 2021; Ritchie, 2021). On the plus side, regarding carbon sequestration by soybean crops, a recent study in part of Mato Grosso State in Brazil reported that rates of assimilation were higher than CO2 emissions caused by some of the anthropogenic activities during cultivation, albeit in the context of remediation measures such as rotations with cereals and no-till in order to retain soil carbon (Agomoh et al, 2021; De Lima et al, 2022; Toloi et al, 2024). In a direct comparison between soybean and oil palm the LUC cost for transitions from natural vegetation to cropland on mineral soils over a 20-year period ranged from −4.5 to 29.4 t CO2-eq/ha/yr for oil palm, whereas soybeans had a much higher range from +1.2 to 47.5 t CO2-eq/ha/yr (Flynn & Canals, 2012).

In a recent review, the issue of deforestation caused by the rapid expansion of soybean cultivation was addressed (Murphy, 2024b). In the short to medium term, such deforestation is principally caused by economic factors. Hence, forest clearance for pasture or soybean cultivation in Brazil is often motivated by prospects of increased future demand for meat or grain products. Another factor is that, after a few years, forest land cleared for soybean production often becomes less productive as nutrients are depleted or the soil structure is otherwise unsuitable, which can lead to yet more rounds of self-destructive land clearance (Critchley & Bruijnzeel, 1999; Odhiambo, 2022; Pendrill et al, 2022a). There are some parallels here with the responses to previous expansion in oil palm cultivation (Bausano et al. 2023; WTO, 2024) although, as noted above, this has been greatly reduced since the 2010s (Murphy, 2024b). In the case of soybean, there has been some pressure for downstream users and/or governments to impose moratoriums and/or voluntary restrictions on soybean products including those derived from its oil (Leijten et al, 2023).

A major drawback of such measures is a danger that the restricted crop is simply grown elsewhere, a phenomenon known as ‘leakage’ (Villoria et al, 2022). As noted by Murphy (2024b), the EU is a major proponent of moratoriums related to deforestation, but in late 2024 it was obliged to postpone the implementation of its controversial scheme known as European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) (Hasan et al, 2025; World Economic Forum, 2025). One of the issues regarding soybeans is that the EU is a major importer and hence complicit in their embedded or embodied tropical deforestation. In recent years the EU was obliged to recognise that its soybean imports are in effect outsourcing the environmental impact of its own food consumption and hence shifting it to growing countries, mostly in the tropics. By this logic, it was estimated that such outsourced tropical deforestation makes up one sixth of the carbon footprint of a European citizen’s diet, although this figure is often allocated instead as a carbon debit for the producing countries (Bausano et al, 2023; Joint Research Centre, 2024). As applied to the consumption of imported oil palm products, it is estimated that a typical European citizen has been responsible for the historical deforestation of 40 to 80 m2 of tropical forest (Bausano et al, 2023). One caveat here is that there have been allegations that parties on all sides sometimes use moratoriums based on such data to restrict certain crop imports to protect local markets rather than for environmental reasons (WTO, 2024).

As expected for such a short, non-woody crop that actively photosynthesises for a only few months each year, soybeans do not contribute greatly to carbon sequestration and are far less effective than tropical tree crops in terms of balancing the global carbon cycle (Murphy, 2024b; 2024c). Indeed, the crop has a strongly negative net carbon balance. The 160% expansion in Brazilian soybean cultivation since 2000 has mainly taken place in high biodiversity value biomes, such as tropical forests and cerrado (Delzeit et al, 2017); Meijaard et al, 2024). It was recently estimated that soybean production in the Brazilian cerrado, where much of the crop is grown, resulted in net CO2 emissions of ~52 Mt/yr, primarily due to LUC (42%) and road transportation (26%) (Meijaard et al, 2024). Soybean production in cerrado biomes accounted for the entire emission footprint of the crop. Deforestation-induced microclimate changes were also noted, with local temperatures rising by <3.5oC following forest clearance and a 44% reduction in evapotranspiration in converted areas (Chain Action Research, 2018; World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), 2023). These shifts could generate a 12% decrease in soy yield, resulting in an annual income loss for growers of $100/ha. Unfortunately, such losses could increase pressures for yet more land clearance and/or further unsustainable intensification practices in order to recoup the lost investments and profits.

In summary, soybean produces a substantial 68 Mt/yr oil yield, but requires a very large land area of 130 Mha. During its relatively short annual growing season it has a low capacity to sequester atmospheric CO2 and apart from its seed, it produces very little useful biomass. The crop also requires high mineral fertiliser inputs for commercial yields and can have high LUC, and hence GHG emission, costs unless alternative cultivation measures such as no-till are used to retain soil carbon. Similarly to oil palm, but more recently, soybean cultivation has come under increasing scrutiny due to its expansion into high-biodiversity tropical regions, such as Amazonia and the cerrado in Brazil. Unlike oil palm, however, much of the newly converted soybean cropland is used to supply the animal feed industry either locally or via export, especially to China.

4. Rapeseed/Canola

Rapeseed (canola),

Brassica napus, is the third most important vegetable oil crop and its 27 Mt/yr oil production comprises 13.4% of the global market, worth an annual

$32 billion. This annual crop is grown over 37 Mha, mainly across the temperate latitudes of 20

o to 55

o N and 20

o to 40

o S (see

Figure 6). The major rapeseed exporter is Canada while other centres of production such as Europe, China and India, largely supply local markets (Rapool, 2024; USDA, 2025). Over recent years the rapeseed market has been in a state of flux, especially in Europe where large quantities of the oil were diverted away from edible consumption and instead used for the manufacture of biodiesel fuel. Climatic factors have also affected both Canadian and European rapeseed production with some of the shortfall being supplied by imports from Australia and from a surprisingly resilient Ukraine (Farmonaut, 2025).

In milder climates rapeseed is sown in early autumn and overwinters as a small ground-hugging rosette that has a brief growing season of ~90 days, while in cooler climates, such as Canada and Scandinavia, the crop is sown in spring and has a longer ~180 day growing season. In both cases the mature crop is 1.0 – 1.7m in height. Rapeseed oil originally mainly contained the C22 monounsaturate, erucic acid, but in the 1960s new varieties enriched in oleic acid were developed and these now make up >99% of global crop production. Meanwhile the early reports on the putative toxicity of erucic acid to humans have been challenged and high-erucic oils are still commonly consumed in Asia (Galanty et al, 2023; Mohanty et al, 2025). Commodity rapeseed oil is now categorised as a high-oleic product with 70-80% levels of this monounsaturate that are comparable to other annual crops, such as soybean and sunflower, and the perennial-crop-derived olive oil (Raatz et al, 2018; Pilorgé, 2020; Murphy, 2024a).

Rapeseed is a similar crop to sunflower in which the major economic product is an oil that makes up about 45-50% seed weight, plus a much smaller meal fraction used as a byproduct for animal feed. Annual production of rapeseed meal is only 39 Mt whereas that of soybean meal is 252 Mt. Both rapeseed and sunflower crops have high chemical input requirements although rainfed rapeseed varieties, some of which are moderately drought tolerant, can be grown in climates as diverse as Finland in Northern Scandinavia to the more arid regions of Rajasthan in India (Kaur & Singh, 2023). In terms of future climate impacts, modelling data show that both rapeseed and sunflower crops face considerable challenges. For example, rapeseed yields might decline between 25–42% by 2070 in Canada (Qian et al, 2018), with similar predicted decreases in Europe, particularly in southern regions (Pullens et al, 2019).

In a recent study, the use of different cropping systems was analysed in potentially susceptible regions in eastern Canada (Ma et al, 2023). The authors identified that cool season rapeseed production is threatened by increasing heat and drought stresses with a need to develop new agronomic solutions, such as eco-friendly fertilisers, stress-resistant varieties, use of plant growth-promoting bacteria and beneficial micronutrients to mitigate abiotic stresses. They reported that crop rotations significantly improved yield while lowering the overall C footprint. For example, compared to continuous monocultures of rapeseed, maize or wheat, diversified cropping systems increased crop yields by an average of 32% and reduced the C footprint of all rotations by 33%, except under severe heat and drought conditions (Ma et al, 2023).

In one of the few direct comparisons of the carbon footprints of rapeseed and oil palm using an LCA SIMAPRO approach, the carbon footprints of field growth and oil processing stages were 1.05 and 0.88 t CO2-eq/t oil respectively, showing a favourable footprint for oil palm versus rapeseed (Tarigan et al, 2025). Interestingly, the combined LUC field growth and processing footprints were also favourable for oil palm grown on mineral soils, which had a lower score of 2.37 t CO2-eq/t oil than rapeseed at 3.14 t CO2-eq/t oil. The two main factors for lower overall LCA scores for rapeseed crops were their comparatively low yields and higher fertiliser requirements. As discussed above, however, when a similar analysis was performed using data from oil palm grown on peatland, the LCA score was highly unfavourable compared to rapeseed (Tarigan et al, 2025).

There are significant concerns about limitations in many of the approaches to LCA taken in studies over the past few decades, and especially their reliability in providing robust data for addressing important policy issues, e.g. regarding agriculture and climate change. For example, individual lobby groups including industry concerns and NGOs sometimes provide misleading data that is then incorporated into the official policies of governments and supranational groups such as the EU. Hence in a study by scientists from Jena, Germany, serious deficiencies were uncovered in baseline data used in the EU Renewable Energy Directive (RED) that related to the supposed ability of rapeseed biodiesel to save GHG emissions (Pehnelt & Vietze, 2012). In the words of the authors “… we are not able to reproduce the GHG emissions saving values published in the annex of RED. Therefore, the GHG emissions saving values of rapeseed biodiesel stated by the EU are more than questionable. Given these striking differences as well as the lack of transparency in the EU’s calculations, we assume that the EU seems to prefer ‘politically’ achieved typical and default values regarding rapeseed biodiesel over scientifically proven ones” (author stress).

One criticism of classical LCA studies is their poor spatial and temporal resolution (Reap et al., 2008). This can be addressed by improving the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of LCA by integrating geographic information systems (GISs) (Gasol et al, 2011; O'Keeffe et al., 2016b; Escobar et al, 2020; Yang et al, 2022). As part of this approach, remote sensing technology has recently been used for an improving rapeseed carbon footprint evaluation in the Chengdu rapeseed producing area of China (Yang et al, 2024). These more detailed data reinforce other studies from Latvia (Fridrihsone et al, 2020) concerning the role of inorganic fertiliser as a major component of both upstream and downstream GHG emissions during rapeseed cultivation. The latter LCA studies also show that autumn-sown rapeseed crops result in much lower GHG emissions compared to spring-sown varieties as well as higher oil yields in the former case.

A frequently overlooked aspect of both rapeseed and soybean cultivation is their negative LUC impact on biodiversity and carbon sequestration compared to the original vegetation in temperate regions such as Canada. For example, 49 Mha of forest loss occurred in Canada due to new rapeseed and soybean planting between 2001 and 2022 (Meijaard et al, 2024). Similarly, the replacement of temperate prairie/steppe native grassland with rapeseed, as has been the case in much of North America, can result in reduced net rates of carbon sequestration. The only example of a positive LUC outcome was the use of no-till, manure-enhanced rapeseed in which case where the crop stored 11.75 t carbon/ha more than the native vegetation (Alcock et al, 2022). In summary, rapeseed produces a modest 27 Mt/yr oil on a relatively large land area of 37 Mha. During its relatively short annual growing season it has a low capacity to sequester atmospheric CO2 and, apart from its seed, it produces very little useful biomass. The crop also requires high mineral fertiliser inputs for commercial yields and can have high LUC, and hence GHG emission, costs unless rotation systems are used for cultivation.

5. Sunflower

Sunflower,

Helianthus annuus, is the fourth most important vegetable oil crop which has experienced a five-fold production increase between 1975 and 2018 (Vear et al, 2003; Pilorgé, 2020). Currently, its 21 Mt/yr oil production make up 13.4% of the global vegetable oil market and is worth an annual

$21 billion. It is grown in many temperate climates as a short-season annual crop across latitudes from 50

o N to 45

o S. As shown in

Figure 7, about two thirds of global sunflower cultivation takes place in the southern part of Europe, from Iberia to the Urals. Russia and Ukraine alone account for almost half of global production, although this has decreased since the 2023 Russian invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent disruption of supply chains of both grain and refined oil. Other smaller centres of production are found in Argentina and the prairies of North America. Global production of sunflower oil uses a crop area of 26 Mha with a current value in the range of

$20-25 billion.

Mature sunflower plants typically reach 1-2m in height by the end of their ~120 day growing season. The crop yields 0.9–1.2 t oil/ha, which is comparable to rapeseed and higher than soybean, but far less that oil palm. There are three major types of sunflower crop, namely the main commodity varieties with a market share of >90% that contain 70% linoleic acid in their oil, plus several newer varieties with a market share of ~10% contain either mid-oleic (65%) or high oleic (<85%) seed oils (Cognitive Market Research, 2025). The mid- and high-oleic sunflower varieties have favourable nutritional properties and command a price premium as they compete with other high-oleic vegetable crop varieties, including soybean (73%) and rapeseed (75%) (Raatz et al, 2018; Pilorgé, 2020; Business Research Insights, 2025).

Although sunflowers are relatively tolerant to low soil moisture, irrigation is still required for optimal yields where it can provide a productivity benefit of 3.5-fold compared to rainfed crops (Figueiredo el al, 2017). In major production areas such as Ukraine sunflower crops have a high environmental water stress index responsible for 70% of the blue water footprint of the oil (Jefferies et al, 2012). Sunflower production often occurs under semi-arid conditions that are associated with low potential for carbon sequestration (Figueiredo el al, 2017; Debaeke & Izquierdo, 2021; Pacci & Dengiz, 2023). These factors render sunflower cultivation susceptible to most climate-change scenarios, especially in Europe where any improvement in northern latitudes, such as Germany, would be greatly offset by declines in southern and eastern regions, particularly in Mediterranean biomes where a 2oC temperature rise could reduce yields by 5-20% by 2030 (Debaeke et al, 2017; Murphy, 2024a).

There are relatively few published studies of sunflower crops regarding their carbon sequestration credentials, GHG emissions or LCA costs. However, in general sunflowers tend to be similar in most aspects to other annual oil crops in terms of comparatively low oil yields and high input requirements (Suardi et al, 2024). In terms of its wider environmental performance, the energy demand of sunflower, as estimated in Chile, was 6.4 GJ/t seed, with mineral fertilisers responsible for the highest environmental impact (Iriarte et al, 2010). It was recommended that the use of degraded grassland for future could considerably reduce the LUC cost and hence reduce net GHG emissions. In a comparative study of soybean and sunflower production systems in the Brazilian cerrado biome, both oil crops had higher climate impacts, measured as net CO2-eq, when grown as continuous monocultures in comparison to within crop rotations (Matsuura et al, 2017). Interestingly, one possibility is to alternate soybean and sunflower crops in a legume/non-legume rotation system in which both partners are vegetable oil producers.

In a comparison of the environmental impacts of major vegetable oil crops, the estimated GHG emissions of both sunflower and rapeseed oils were ~3kg CO2-eq while the land use requirement of sunflower was higher at 18 m2/yr to produce 1kg oil with rapeseed requiring 10 m2/yr in comparison to the extremely low footprint of oil palm at a mere 2.4 m2/yr (Poore & Nemecek, 2018; Meijaard et al, 2024). However, caution is necessary for extrapolating from localised studies of crops (such as sunflower) in one region to crops in other disparate regions of the world where agronomic practices may be quite variable. In one example, an LCA study of sunflower oil for biofuel use in Italy revealed very large variations in the calculation of the CO2 equivalent emissions even within this well-defined and limited LCA value chain (Chiaramonte & Recchia, 2010).

In summary, sunflower produces a modest 21 Mt/yr oil on a relatively large land area of 26 Mha. During its relatively short annual growing season it has a low capacity to sequester atmospheric CO2 and, apart from its seed it produces very little useful biomass. The crop also requires irrigation and high mineral fertiliser inputs for commercial yields and can have high LUC, and hence GHG emission, costs unless degraded grassland is used for cultivation. Finally, future oil yields of sunflowers are probably more susceptible to predicted climatic shifts that entail more erratic rainfall patterns.

6. Environmental Comparisons Between the Major Vegetable Oil Crops

Over recent years several empirical studies and analytical reviews have focused on more in-depth and realistic assessments of the environmental costs of the major vegetable oil crops and their respective capacities for carbon sequestration (Muñoz & Dalgaard, 2014; Schmidt, 2015; Alcock et al, 2022; Murphy, 2024b; Safitri et al, 2024; Murphy et al, 2025; Murphy et al, 2005). One of the most contentious issues is the LUC costs of oil crop cultivation although, as discussed above in section 2, caution should be applied when using either LUC or LCA data unless their reliability, scope and provenance are fully investigated. Regarding oil crop LUC data, the received wisdom in many quarters has long been that oil palm fares far worse than annual crops, despite its lower land footprint and higher oil yields. However, when the emissions for transitions from natural vegetation to cropland on mineral soils in 20 oilseed producing countries were assessed over a 20-year period, the oil palm values ranged from −4.5 to 29.4 t CO2-eq/ha/yr whereas soybeans ranged from +1.2 to 47.5 t CO2-eq/ha/yr (Flynn & Canals, 2012).

A comparison of the four major vegetable oil crops also concluded that optimal results in terms of carbon storage potential were associated with high-yielding crops or, less frequently, by growing moderate-productivity crops on land that was previously of low native productivity (Alcock et al, 2022). In another study, the water footprints of various oil crops and their water requirements for producing a tonne of oil varied considerably with the highest water footprint found in sunflower at 6,800 m3 while soybean, rapeseed, and palm oil required 4,200 to 5,000 m3 (Mekonnen & Hoekstra, 2010).

LCA data can be equally complex and problematic in terms of their interpretation, particularly when new evidence is found that contradicts some of the previous assumptions, some of which have become enshrined in current policies by governments or trading bodies. Hence, there are concerns that energy requirements for oilseed crop cultivation, most of which comes from fossil fuels, have been underestimated. For example, recent meta-analysis data suggest that the energy consumption of open-field agriculture in the EU, most of which comes from non-renewable sources, has been greatly underreported (Paris, 2022). In particular, significant energy inputs such as mineral fertiliser and pesticide production are not necessarily assigned to the agriculture category and might not even appear on an LCA crop audit. The authors conclude that: “there is need for the development and application of detailed and standardized methodologies for energy use analysis of agricultural systems” (Paris, 2022). It appears that the scope and methodologies used in many LCA studies tend to lack consistency, even within a single region such as Europe (Paris, 2022). This makes it difficult to use LCA data to compare different cropping systems worldwide and to draw reliable conclusions about their respective merits and demerits.

As noted previously, most LCA studies have inherent limitations but their data can still be useful, providing these limitations are recognised. For example, the LCA performance of oil palm was found to be comparable to, and sometimes superior to, temperate oil crops (Schmidt, 2015). Other examples include studies of water-use efficiencies, which showed that palm oil had considerably higher efficiencies than other crop oils and was even more effective compared to animal-based fats (Sadras (2008; Mekonnen et al, 2010; Safitri et al, 2024; Boev, 2024; Muñoz & Dalgaard, 2014). In another study, the environmental performances of five major vegetable oil crops were also compared (Muñoz & Dalgaard, 2014). For GHG emissions (including potentially misleading LUC data), the three major temperate oilseed crops had lower levels than oil palm, whereas for land use efficiency, the situation was reversed, with the oilseed crops performing significantly worse. In contrast, sunflower and rapeseed scored better in this study than oil palm and soybean in terms of water use efficiency, although this was contradicted by the studies of Mekonnen & Hoekstra (2010) and Jefferies et al (2012).

In another study, oil palm performed better for GHG emissions provided that methane capture at mills was employed (Efeca, 2022). On the negative side, when LUC was incorporated into the LCA calculations, GHG emissions from oil palm crops were always substantially increased, an effect that was (unsurprisingly) most marked when considering crops grown on peat-rich soil. Unfortunately the complexity of peat soil composition means that carbon flux data can vary considerably between regions, and even within a single large plantation where several types of peat may be present. It also means that the auditing of carbon flux on former peatland can be imprecise and this is reflected by the wide variations in published data as recently reviewed by (Murphy, 2024b). More recent analyses have given some cause for qualified optimism regarding the reversal of some of the initial LUC damage in the case of peatland conversion to oil palm. Hence, the rewetting of drained peatlands on oil palm plantations in West Kalimantan, Borneo that have become degraded has been claimed to reduce CO2 emissions by as much as 3.9 Mt/yr (Parish, 2023; Novita et al, 2024). This is particularly interesting in view of the growing calls for the withdrawal of peatlands from oil palm cultivation (Afriyanti et al, 2019). Other efforts are underway to restore or otherwise ameliorate the damage done to tropical peatlands, for example by minimising drainage (Daud et al, 2019; Scholz et al, 2023; Yunus, 2024). Meanwhile recent evidence shows that peatland has declined from 21% to a mere 7% of oil palm land conversion (Nusantara Atlas (2025).

Other measures for reducing land use requirements, and hence decreasing LUC values, include breeding for increased oil yields, more widespread replanting of superior genotypes, reducing inputs that have high carbon footprints (such as fertilisers), eliminating carbon-emitting deforestation and the use of sensitive peatland habitats, and the more widespread adoption of methane-capture technologies in processing mills as reviewed recently (Murphy, 2024b). Relevant studies include Patthanaissaranukool & Polprasert, 2011; Global Methane Initiative, 2015; Leijten et al, 2013; Loh et al, 2017; 2019; Schmidt & De Rosa, 2020; Alcock et al, 2022; Xin et al, 2022; Ariesca et al, 2023; Frianto et al, 2024; and Tan et al, 2024. In addition to the impact of emissions on LUC, it is also important to include metrics that capture biodiversity impacts of different land uses. For example, losses in species richness are significantly lower when oil palm replaces rubber plantations or logged-over forest as opposed to pristine forest, meaning that in the two former cases biodiversity had already been impoverished and therefore the change to oil palm was much less acute (Koh & Wilcove, 2008).

As noted above in section 3 in the case of oil palm, there is considerable scope for substantial yield increases due to factors such as germplasm improvement followed by vigorous replanting programmes that could generate two- to three-fold more oil yield per hectare. This could be supplemented through improved management practices as seen by the existing two-fold yield gap between some of the best plantations yielding 6.3 t/ha compared to the global average yield of 3.3 t/ha. This phenomenon, termed the ‘yield gap’ applies across the board to crop yields in general and improved crop management has also been identified as a key factor in addressing it in all of the sectors studied (Lobell et al, 2009; Mueller et al, 2012). By closing such yield gaps, it would also possible to minimise LUC costs and reduce the environmental footprint of the crop in question (Van Ittersum et al 2013; Clay, 2011; Tilman et al, 2011; Phalan et al, 2014; 2016; Suh et al, 2020; Beyer & Rademacher, 2021).

These considerations apply to all crops as there are clearly considerable discrepancies across regions and countries that are largely the result of differences in crop management (Beyer & Rademacher, 2021). Such yield gaps are particularly apparent when comparing cereal staples such as maize where yields in the USA are as much as three-fold higher than in sub-Saharan Africa (Aramburu-Merlos et al, 2024; Global Crop Yield Atlas, 2024). However, they are also seen in other crop systems where the kind of stagnation already described above for oil palm has been observed recently (Gerber, et al, 2024). It would be useful, therefore, for the oil palm sector to address its own considerable yield gaps in the light of the considerable amount of new research that is emerging in this area. The rewards of reducing such yield gaps are self evident, not only in the increases in industry-wide profitability, especially for smallholders, but also in avoiding the need for excessive land expansion in the future and the commensurate environmental benefits that would accrue to all stakeholders throughout the supply chains.

The oil palm sector also needs to embrace recent advances in areas such as acquiring increasingly granular datasets, for example using high-resolution AI/imaging technologies that can operate in real time. These would allow the generation of more reliable and up-to-date metrics such as LUC and LCA. As we have seen, one of the difficulties in producing realistic LUC figures is the immense variability in the baseline data from different locations. For example, in the case of tropical forests it has long been known that even in a single location the N2O emissions can vary by a factor of 6-7-fold from one year to the next (Kiese & Butterbach-Bahl, 2003; Schmidt, 2007). Such variations may be due to differences in soil types, precipitation, and measurement/modelling methods. Taken together, many of the above findings, especially the more recent ones that are typically not included in LUC analyses, suggest that a systematic recalibration of LUC data is required in order to provide more accurate baseline ranges for use by stakeholders across the oil palm sector. These new analytical tools have the potential to provide credible and transparent datasets that allow the commercial and environmental performance of all vegetable oil crops to be compared on a rigorous and systematic basis.

7. Conclusions

The three major annual crops, soybean, rapeseed and sunflower, produce compositionally similar vegetable oils dominated by C16 and C18 fatty acids and together supply about 52% of the world’s supply of vegetable oil on an extensive land footprint totalling 203 Mha.

In contrast, the perennial oil palm crop supplies 40% of the world’s supply of vegetable oil on a more modest land footprint of a mere 23 Mha, making it almost ninefold more efficient in terms of oil production per land unit.

As a perennial crop, oil palm has many environmental advantages over annual crops including its already high, but greatly improvable, oil yields, its capacity for carbon sequestration comparable with some forests, its lower vulnerability to currently predicted climate effects, and its future capacity for considerably increased sustainable production without expansion into sensitive natural habitats.

Global requirements for vegetable oils will continue to grow over the coming decades, although supplies might become increasingly constrained due to factors such as climate change and poor land use.

This might require a re-examination of the current focus on comparatively low-yielding, climate-sensitive annual oil crops alongside a more effective and imaginative use of improved and updated versions of high-yielding, land-sparing oil palm cropping systems.

Abbreviations and Units

| C |

carbon |

| EU |

European Union |

| EUDR |

European Union Deforestation Regulation |

| GHG |

greenhouse gas |

| Gt |

giga (billion) tonnes |

| Ha |

hectare |

| m |

metres |

| LCA |

life cycle analysis |

| LUC |

Land Use Conversion |

| Mha |

million hectares |

| Mt |

million tonnes |

| $ |

USD in 2024 prices |

| RED |

Renewable Energy Directive |

| SDGs |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| t |

tonnes |

| yr |

year |

References

- Afriyanti, D; et al. Scenarios for withdrawal of oil palm plantations from peatlands in Jambi Province, Sumatra, Indonesia. Reg Environ Change 2019, 19, 1201–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agomoh IV et al Crop rotation enhances soybean yields and soil health indicators. Soil Sci. Soc. America J. 2021, 85, 1185–1195. [CrossRef]

- Ahirwal J et al Oil Palm Agroforestry Enhances Crop Yield And Ecosystem Carbon Stock In Northeast India: Implications For UN Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainable Production Consumption 2022, 30, 478–487. [CrossRef]

- Albrecht A, Kandji ST Carbon sequestration in tropical agroforestry systems. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 2003, 99, 15–27. [CrossRef]

- Alcock TD et al More sustainable vegetable oil: Balancing productivity with carbon storage opportunities, Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 829, 154539. [CrossRef]

- Business Insider (2025) https://markets.businessinsider.

- Aramburu-Merlos F et al Adopting yield-improving practices to meet maize demand in Sub-Saharan Africa without cropland expansion. Nature Commun 2024, 15, 4492. [CrossRef]

- Ariesca R et al Land Swap Option for Sustainable Production of Oil Palm Plantations in Kalimantan, Indonesia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2394. [CrossRef]

- Baer DJ et al Consumption of High-Oleic Soybean Oil Improves Lipid and Lipoprotein Profile in Humans Compared to a Palm Oil Blend: A Randomized Controlled Trial, Lipids 2021, 56, 313-325. 56. [CrossRef]

- Bausano, G; et al. Food, biofuels or cosmetics? Land-use, deforestation and CO2 emissions embodied in the palm oil consumption of four European countries: a biophysical accounting approach. Agric Econ 2023, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer R, Rademacher T Species Richness and Carbon Footprints of Vegetable Oils: Can High Yields Outweigh Palm Oil’s Environmental Impact? Sustainability 2021, 13, 1813. [CrossRef]

- Boev P et al (2024) The Environmental Impact of Food, on Climate, Forests, Land, Water, and Air, Profundo. Amsterdam, The Netherlands. https://wwfeu.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/240429_report-profundo-wwf_final.

- Borchard N et al Deep soil carbon storage in tree- dominated land use systems in tropical lowlands of Kalimantan. Geoderma 2019, 354, 113864. https://www.cifor–icraforg/knowledge/publication/7354/. [CrossRef]

- Brindis-Santos AI et al Impacts of oil palm cultivation on soil organic carbon stocks in Mexico: evidence from plantations in Tabasco State. Cahiers Agricultures 2021, 30, 47. [CrossRef]

- Business Research Insights (2025) Sunflower Oil Market Size, Share, Growth, and Industry Analysis, By Type (Linoleic Oil, Mid-Oleic Oil, High-Oleic Oil), And By Application (Food, Biofuels, Cosmetics, Other), and Regional Forecast to 2033. https://www.businessresearchinsights. 1187.

- Button ES et al Deep-C storage: Biological, chemical and physical strategies to enhance carbon stocks in agricultural subsoils, Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 170, 108697. [CrossRef]

- Chain Action Research (2018) Cerrado Deforestation Disrupts Water Systems, Poses Business Risks for Soy Producers. https://chainreactionresearch.

- Chandran MR Future viability and sustainability of plantation crops. Malay Oil Sci Technol. 2019, 28, 56–60.

- Chapman EA Perennials as Future Grain Crops: Opportunities and Challenges. Frontiers Plant Sci 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Cheah LW et al Potential carbon stock and management of carbon in oil palm plantations on mineral soils. AAR Newsletter Oct 2015, 2015, 4–7.

- Chiaramonte D & Recchia L Is life cycle assessment (LCA) a suitable method for quantitative CO2 saving estimations? the impact of field input on the LCA results for a pure vegetable oil chain, Biomass Bioenergy 2010, 34, 787–797. [CrossRef]

- Choksi P et al How do trees outside forests contribute to human wellbeing? A systematic review from South Asia, Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 034040. [CrossRef]

- Clay J Freeze the footprint of food, Nature 2011, 475, 287–289. 475. [CrossRef]

- Cognitive Market Research Sunflower Seed Oil Market Report 2025, 2025. 2025.

- https://www.cognitivemarketresearch.com/sunflower-seed-oil-market-report?

- Corley RHV, Tinker PB (2015) The oil palm. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

- Cox TS et al Prospects for Developing Perennial Grain Crops. BioScience, 2006, 56, 649–659. [CrossRef]

- Critchley WR, Bruijnzeel LA (1999) Environmental impacts of converting moist tropical forest to agriculture and plantations. IHP humid tropics programme series. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco. 4822.

- Daud NN et al (2019) Carbon Sequestration in Malaysian Oil Palm Plantations – An Overview: Towards a Sustainable Geoenvironment, Proc 8th Int Congress on Environmental Geotechnics 3, 49-56. [CrossRef]

- Dawson D (2022) How Intensive Agriculture and Olive Cultivation Impact Soil Health. Olive Oil Times. 1134.

- Debaeke P et al Sunflower crop and climate change: vulnerability, adaptation, and mitigation potential from case studies in Europe. OCL 2017, 24, D102. [CrossRef]

- Debaeke P, Izquierdo NG Sunflower, in: Crop Physiology Case Histories for Major Crops, Ch 2021, 16, pp 482-517, Eds: Sadras VO, Calderini DF, Academic Press, ISBN 9780128191941. [CrossRef]

- De Barros PHB et al Mapping oil palm expansion in the Eastern Amazon using optical and radar imagery, Remote Sensing Applications: Society Environment 2025, 38, 101506. 38. [CrossRef]

- Deines C (2024) The Global Environmental Consequences of Palm Oil Production: The Role of Industrial Polyculture in Sustainable Solutions, Western Carolina University. https://affiliate.wcu.edu/rasc/wp-content/uploads/sites/298/2025/03/Deines.

- De Lima CZ et al (2022) Greenhouse Gases Mitigation Potential of Soy Farming Decarbonization Actions to be Taken by 2030. Observatório de Conhecimento e Inovação em Bioeconomia, /: Brasil. https, 2023.

- Delzeit, R; et al. Addressing future trade-offs between biodiversity and cropland expansion to improve food security. Regional Environ. Change 2017, 17, 1429–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descals A et al (2025) Extensive Unreported Non-Plantation Oil Palm in Africa, preprint. https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202502. 1589.

- Dhyani SK et al (2020) Agroforestry for Carbon Sequestration in Tropical India. In: Ghosh P et al. (eds) Carbon Management in Tropical and Sub-Tropical Terrestrial Systems. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Efeca Carbon Emissions and Palm Oil Efeca Briefing Note 22, 2022. https://www.efeca.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Palm-Oil-and-Carbon-Emissions_final. 20 January.

- Escallón-Barrios M et al Improving harvesting operations in an oil palm plantation. Annals Operations Res. 2020, 314, 411–449. [CrossRef]

- Escobar N et al Spatially-explicit footprints of agricultural commodities: Mapping carbon emissions embodied in Brazil's soy exports, Global Environ Change 2020, 62, 102067. 62. [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT (2025) FAO Statistical Database. https://openknowledge.fao. 9272.

- Farmonaut (2025) EU Rapeseed Supply Crunch: Global Canola Market Trends and Trade Flow Dynamics for 2024-25.

- https://farmonaut. 2024.

- Feintrenie L et al Oil palm in Mexico and in the Americas. Cahiers Agricultures 2025, 34, 11. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo F el al Life-cycle assessment of irrigated and rainfed sunflower addressing uncertainty and land use change scenarios, J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 436–444. [CrossRef]

- Flynn HC, Canals LM (2012), Quantifying global greenhouse gas emissions from land-use change for crop production, Glob Change Biol 18:1622–1635. [CrossRef]

- Freibauer A et al Carbon sequestration in the agricultural soils of Europe, Geoderma 2004, 122, 1-23. 122. [CrossRef]

- Frianto, D; et al. Carbon stock dynamics of forest to oil palm plantation conversion for ecosystem rehabilitation planning. Global J. of Environ. Sci. Mgt. 2024, 10, 1593–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridrihsone et al Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Rapeseed and Rapeseed Oil Produced in Northern Europe: A Latvian Case Study, Sustainability 2020, 12, 5699. https://www.mdpi. 2071.

- Galanty et al Erucic Acid—Both Sides of the Story: A Concise Review on Its Beneficial and Toxic Properties. Molecules 2023, 28, 1924. [CrossRef]

- Gasol CN et al Environmental assessment: (LCA) and spatial modelling (GIS) of energy crop implementation on local scale. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 2975–2985. [CrossRef]

- Gerber, JS; et al. Global spatially explicit yield gap time trends reveal regions at risk of future crop yield stagnation. Nature Food 2024, 5, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghale B et al Carbon Sequestration Potential of Agroforestry Systems and Its Potential in Climate Change Mitigation. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2022, 233, 228. [CrossRef]

- Global Methane Initiative (2015) Resource Assessment for Livestock and Agro-Industrial Wastes – Indonesia. https://www.globalmethane.org/documents/ag_indonesia_res_assessment.

- Global Crop Yield Atlas (2024) Maize production in nine Sub-Saharan African countries. https://www.yieldgap.

- Goodrick I et al Soil carbon balance following conversion of grassland to oil palm. GCB Bioenergy 2015, 7, 263–272. [CrossRef]

- Hanno SL et al High oleic soybean oil maintains milk fat and increases apparent total-tract fat digestibility and fat deposition in lactating dairy cows, J. Dairy Sci. Commun. 2024, 5, 287–292. [CrossRef]

- Hasan F et al The Economic Impact of European Union (EU) on Indonesian Palm Oil Smallholders: Quantitative Approach, Proc. Indo. Focus 2024, 2024, 1–5.

- Hendrawan D, Musshoff O Risky for the income, useful for the environment: Predicting farmers' intention to adopt oil palm agroforestry using an extended theory of planned behaviour, J Cleaner Prod. 2024, 475, 143692. 475. [CrossRef]

- Henson IE (1999a) Comparative Ecophysiology of Oil Palm and Tropical Rainforest. In: Singh et al Eds., Oil Palm and the Environment: A Malaysian Perspective, pp 9-39. Kuala Lumpur.

- Henson IE (1999b) Notes on oil palm productivity. IV. Carbon dioxide gradients and fluxes and evapotranspiration, above and below the canopy. J Oil Palm Res.

- Henson IE A review of models for assessing carbon stocks and carbon sequestration in oil palm plantations. J Oil Palm Research 2017, 29, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Henson, I; et al. The greenhouse gas balance of the oil palm industry in Colombia: a preliminary analysis. I. Carbon sequestration and carbon. Agronomía Colombiana 2012, 30, 359–369 http://wwwscieloorgco/scielophp. [Google Scholar]

- Henson, I; et al. The greenhouse gas balance of the oil palm industry in Colombia: a preliminary analysis. II. Greenhouse gas emissions and the carbon budget. Agronomía Colombiana 2012, 30, 370–378 http://wwwscieloorgco/scielophp. [Google Scholar]

- Hergoualc’h C et al Conversion of degraded forests to oil palm plantations in the Peruvian Amazonia: Shifts in soil and ecosystem-level greenhouse gas fluxes. Agric Ecosysyt. Environ. 2025, 386, 109603. [CrossRef]

- Iriarte A, Rieradevall J, Gabarrell X Life cycle assessment of sunflower and rapeseed as energy crops under Chilean conditions, J Cleaner Prod 2010, 18, 336-345. 18. [CrossRef]

- Isaac J (2019) Industrial revolution 4.0 for smart oil palm mills. Malaysian Oil Sci Technol.

- IUCN (2024) Vegetable oils and biodiversity. Issues Brief.

- https://iucn.

- Jalani BS et al (2002). Elevating the national oil palm productivity: general perspectives. Seminar on Elevating the National Oil Palm Productivity.

- Jefferies D et al Water Footprint and Life Cycle Assessment as approaches to assess potential impacts of products on water consumption. Key learning points from pilot studies on tea and margarine. J. Cleaner Prod 2012, 33, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Research Centre (2024) The Amazon region in 2022 and 2023: deforestation, forest degradation and the risk of growing soy production. EU Science Hub, 2022.

- Kantar MB et al Perennial Grain and Oilseed Crops. Ann Rev Plant Biol, 2016, 67, 703–729. [CrossRef]

- Kaur S, Singh J (2023) Changing cropping pattern of oilseed crops and its diversification: The case of Thar Desert, Rajasthan (1985–1986 to 2015–2016), OCL 30, 13. [CrossRef]

- Keong NW Modernising sales and widening markets. Malaysian Oil Sci Technol. 2019, 28, 32–6.

- Khasanah, N; et al. Oil Palm Agroforestry Can Achieve Economic and Environmental Gains as Indicated by Multifunctional Land Equivalent Ratios. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 3, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiese R, Butterbach-Bahl W N₂O and CO₂ emissions from three different tropical forest sites in the wet tropics of Queensland, Australia, Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 975–987. [CrossRef]

- Koh LP, Wilcove DS Is oil palm agriculture really destroying tropical biodiversity? Conserv. Lett. 2008, 1, 60–64. [CrossRef]

- Koussihouèdé H et al Comparative analysis of nutritional status and growth of immature oil palm in various intercropping systems in southern Benin. Exp. Agric. 2020, 56, 371–386. [CrossRef]

- Kreitzman M et al Perennial Staple Crops: Yields, Distribution, and Nutrition in the Global Food System. Frontiers Sustain Food Systems,. [CrossRef]

- Kumar BM, Nair PKR (2011) Carbon Sequestration Potential of Agroforestry Systems: Opportunities and Challenges. Advances in Agroforestry, /: Singapore. ISBN 978-94-007-3777-8. https, 3777.

- Kuschnig, N; et al. Spatial spillover effects from agriculture drive deforestation in Mato Grosso, Brazil. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 21804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lal R et al The carbon sequestration potential of terrestrial ecosystems. J Soil Water Conservation 2018, 73, 145A–152A https://wwwtandfonlinecom/doi/abs/102489/jswc736145A.

- Lamade E, Bouillet JP Carbon storage and global change: the role of oil palm. Oilseeds & Fats Crops and Lipids 2005, 12, 154–160.

- Lee J et al Oil palm smallholder yields and incomes constrained by harvesting practices and type of smallholder management in Indonesia. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 501–513. [CrossRef]

- Lee JTC (2025) Oil Palm : Inconvenient truth, brewing crises, Borneo Post 23 Feb 2025. https://www.theborneopost. 2025.

- Leijten F et al Projecting global oil palm expansion under zero-deforestation commitments: Direct and indirect land use change impacts. iScience 2023, 26, 106971. [CrossRef]

- Lobell DB et al Crop Yield Gaps: Their Importance, Magnitudes, and Causes. Ann. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2009, 34, 179–204. [CrossRef]

- Lobell, DB; et al. Climate Trends and Global Crop Production Since 1980. Science 2011, 333, 616–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, SK; et al. First Report on Malaysia's experiences and development in biogas capture and utilization from palm oil mill effluent under the Economic Transformation Programme. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2017, 74, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, SK; et al. (2019) Biogas Capturing Facilities in Palm Oil Mills: Current Status and Way Forward. Palm Oil Engineering Bulletin No.132, pp 13–17. http://poeb.mpob.gov.

- Luke SH et al Managing oil palm plantations more sustainably: large-scale experiments within the Biodiversity and Ecosystem Function in Tropical Agriculture (BEFTA) Programme. Front Forests Global Change 2020, 2, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Ma BL et al Canola productivity and carbon footprint under different cropping systems in eastern Canada, Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2023, 127, 191–207. [CrossRef]

- Marquer, L; et al. The first use of olives in Africa around 100,000 years ago. Nature Plants 2022, 8, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Nuñez C et al (2024) Tailored policies for perennial woody crops are crucial to advance sustainable development. Nature Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Masure A et al Promoting oil palm-based agroforestry systems: an asset for the sustainability of the sector, Cahiers Agric. 2023, 32, 16. 32. [CrossRef]

- Matsuura M et al Life Cycle Assessment of soybean-sunflower production system in the Brazilian Cerrado, Int J Life Cycle Assess 2017, 22, 492–501. 22. [CrossRef]

- McAlpine CA et al Forest loss and Borneo’s climate. Env. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 044009. [CrossRef]

- Meijaard E et al (2021) Oil Palm Plantations in the Context of Biodiversity Conservation. In Encyclopedia of Biodiversity 3rd edition, Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Meijaard E et al (2024) Exploring the future of vegetable oils. Oil crop implications – Fats, forests, forecasts, and futures. IUCN & SNSB, /: https, 5145.

- Mekonnen MM, Hoekstra AY The Green, Blue and Grey Water Footprint of Crops and Derived Crop Products. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2010, 15, 1577–1600.

- Messier C et al For the sake of resilience and multifunctionality, let’s diversify planted forests! Conservation Lett. 2022, 15, e12829. [CrossRef]

- Micha, R; et al. Global, regional, and national consumption levels of dietary fats and oils in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis including 266 country-specific nutrition surveys. BMJ 2014, 348, g2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo L et al Integrated global assessment of the natural forest carbon potential, Nature 2023, 624, 92-107. 624. [CrossRef]

- Mohanty S et al (2025) Paradoxical Effects of Erucic Acid-A Fatty Acid With Two-Faced Implications. Nutr Rev. /: https, 4020.

- Mohanaraj S, Donough CR Harvesting practices for maximum yield in oil palm: results from a re-assessment at IJM plantations. Sabah. Oil Palm Bull. 2016, 72, 32–37.

- Monzon JP et al Agronomy explains large yield gaps in smallholder oil palm fields, Agric Systems 2023, 210, 103689. 210. [CrossRef]

- Mueller ND et al Closing yield gaps through nutrient and water management. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 490, 254–257. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz I, Schmidt JH, Dalgaard R (2014) Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Five Different Vegetable Oils. In: 9th International Conference LCA of Food, San Francisco, USA. https://lca-net.com/files/Paper-no-165_Munoz_et_al.

- Murphy DJ (2008) People Plants and Genes, the story of crops and humanity, Oxford University Press. ISBN: 9780199207145. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/people-plants-and-genes-9780199207145?

- Murphy DJ Oil palm: future prospects for yield and quality improvements, Lipid Technol. 2009, 21, 257-260. 21. [CrossRef]

- Murphy DJ The future of oil palm as a major global crop: opportunities and challenges, J. Oil Palm Res., 2014, 26, 1–24.