Submitted:

19 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Main Text

Methods

1. Simple Random Sampling for Country-Wide Estimation of Oil Palm Area

1.1. Delimitation of the Sampling Area

1.2. Definition of oil Palm Types

- 1)

- Plantation oil palm: Structured monoculture plantations with homogeneous oil palm age. The plantation has a regular planting pattern and optimal spacing to maximize productivity. These plantations can be corporate-managed (industrial plantations) or owned by small businesses, families or local communities (smallholder plantations). Plantation oil palm can be identified in sub-meter satellite images because of the high planting density and a linear arrangement of palms (Supplementary Figure S2). While industrial plantations show similar characteristics such as large coverage, long linear well-defined boundaries, and dense and equidistant trails placed for optimal harvesting, smallholders are a heterogeneous group with different planting settings. Here, in this category, we include any smallholder contexts with a systematic layout, planting rows, and standardized spacing.

- 2)

- Non-plantation oil palm: oil palm that grows dispersed or disorganized in clusters, with irregular arrangement and lack of strict planting patterns (Supplementary Figure S2). This includes: a) wild oil palm, which grows in naturalized settings coexisting with native vegetation or other plant species, creating a mixed structure that resembles a natural vegetation type rather than a cultivated plantation. This includes truly wild oil palm which was mapped elsewhere [14]; b) smallholder or community-based oil palms that grow close together but lack systematic layout, planting rows, or standardized spacing. In these groves, oil palms grow in irregular patterns due to spontaneous seedling emergence or informal planting methods without planned organization; c) Dispersed oil palms in anthropogenic landscapes: individual or scattered oil palm growing within human-modified environments, such as agricultural fields, villages, roadsides, or mixed-use lands. Our definition of non-plantation oil palm does not distinguish between land owned and managed by smallholders and land where oil palm grows entirely wild, as this information cannot be directly determined from satellite data.

1.3. Visual Interpretation of Satellite Data

1.4. Estimation of Oil Palm Canopy Area

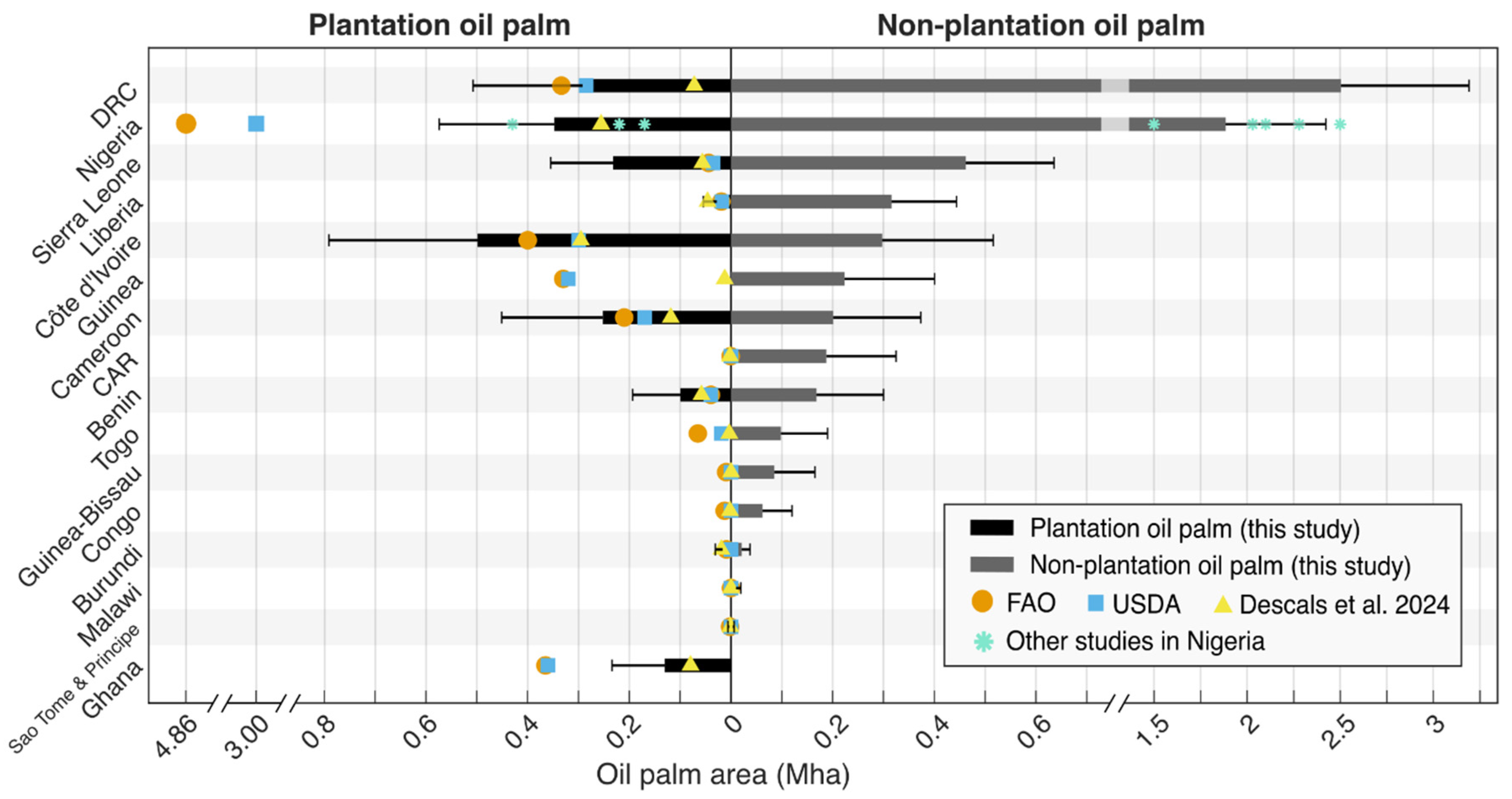

1.5. Comparison with Official and Satellite-Derived Statistics

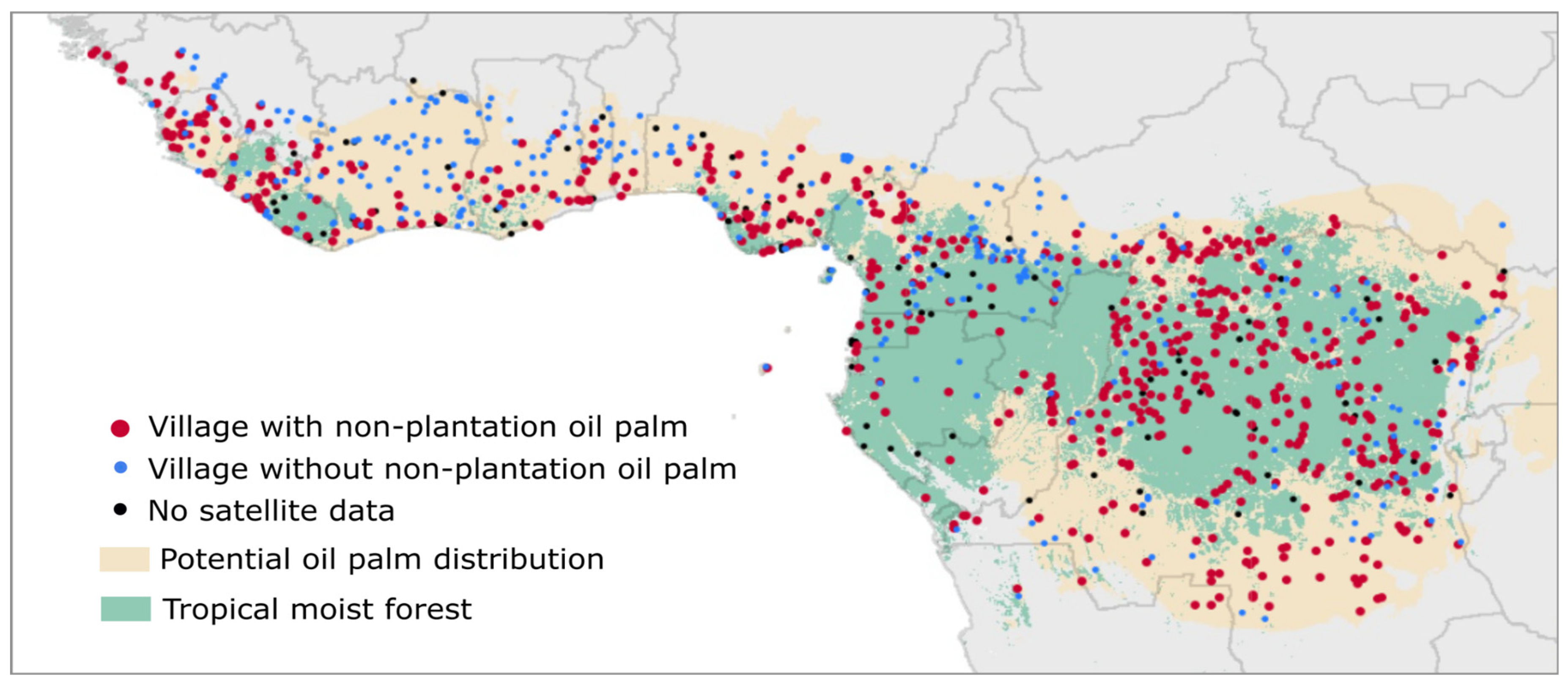

2. Determining the Occurrence of Non-Plantation Oil Palm Within the Proximities of Villages

Data Availability

Competing Interests

Acknowledgment

References

- Corley, R. H. V. & Tinker, P. B. The Oil Palm. (John Wiley & Sons, 2008).

- Sowunmi, M.A. The significance of the oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) in the late Holocene environments of west and west central Africa: A further consideration. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 1999, 8, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAO: FAOSTAT statistical database. (2022).

- Poku, K. Small-Scale Palm Oil Processing in Africa. (Food & Agriculture Org., 2002).

- Carrere, R. Oil palm in Africa: Past, present and future scenarios. WRM series on tree plantations 15, 1–78 (2010).

- Pashkevich, M.D.; Marshall, C.A.; Freeman, B.; Reiss-Woolever, V.J.; Caliman, J.-P.; Drewer, J.; Heath, B.; Hendren, M.T.; Saputra, A.; Stone, J.; et al. The socioecological benefits and consequences of oil palm cultivation in its native range: The Sustainable Oil Palm in West Africa (SOPWA) Project. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 926, 171850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirad, U.S.d.P.; Rafflegeau, S.; Nanda, D.; I, C.U.d.Y.; Genot, C.; Bia, F.I.-U. Artisanal mills and local production of palm oil by smallholders. Achieving sustainable cultivation of oil palm Volume 2: Diseases, pests, quality and sustainability (2018).

- Hyman, E.L. An economic analysis of small-scale technologies for palm oil extraction in Central and West Africa. World Dev. 1990, 18, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borelli, T.; Hunter, D.; Powell, B.; Ulian, T.; Mattana, E.; Termote, C.; Pawera, L.; Beltrame, D.; Penafiel, D.; Tan, A.; et al. Born to Eat Wild: An Integrated Conservation Approach to Secure Wild Food Plants for Food Security and Nutrition. Plants 2020, 9, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Descals, A.; Gaveau, D.L.A.; Wich, S.; Szantoi, Z.; Meijaard, E. Global mapping of oil palm planting year from 1990 to 2021. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 5111–5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint, F. & others. Fats and fatty acids in human nutrition. Report of an expert consultation, 10-14 November 2008, Geneva. (2010).

- Bajželj, B.; Laguzzi, F.; Röös, E. The role of fats in the transition to sustainable diets. Lancet Planet. Heal. 2021, 5, e644–e653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virah-Sawmy, M.; Newing, H.; Ingram, V.; Holle, M.; Pasmans, T.; Omar, S.; Hombergh, H.v.D.; Unus, N.; Fosch, A.; de Arruda, H.F.; et al. Exploring the future of vegetable oils : oil crop implications : fats, forests, forecasts, and futures; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cosiaux, A. , Gardiner, L. & Couvreur, T. Elaeis guineensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e. T13416970A13416973. (2016).

- Ordway, E.M.; Naylor, R.L.; Nkongho, R.N.; Lambin, E.F. Oil palm expansion in Cameroon: Insights into sustainability opportunities and challenges in Africa. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 47, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.J.; Goggin, K.; Paterson, R.R.M. Oil palm in the 2020s and beyond: challenges and solutions. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2021, 2, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijaard, E.; et al. Apes and agriculture. Frontiers in Conservation Science 4, 1225911 (2023).

- Descals, A.; Wich, S.; Meijaard, E.; Gaveau, D.L.A.; Peedell, S.; Szantoi, Z. High-resolution global map of smallholder and industrial closed-canopy oil palm plantations. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 1211–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancutsem, C.; et al. Long-term monitoring of tropical moist forest extent (from 1990 to 2019). 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E. B. Probable inference, the law of succession, and statistical inference. Journal of the American Statistical Association 22, 209–212 (1927).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).