1. Introduction

In 2010, the United Nations recognized access to safe drinking water and sanitation as an essential human right for well-being and health, guaranteeing contaminant-free water for personal and domestic use. In Mexico, this right was included in the fourth article of the Constitution in 2012, establishing that everyone has access to sufficient, safe, and affordable water for personal and domestic consumption. Water (H

2O) is an essential substance for life, as well as for industrial processes and the production of goods [

1]. However, millions of cubic meters of inadequately treated wastewater are discharged each year, causing pollution, serious health problems, and ecological damage due to harmful substances such as microorganisms and chemical compounds in the water [

2]. In the last decade, environmental remediation has emerged as a national and international priority due to contamination from improper disposal of toxic wastes in lagoons, subway storage tanks, and landfills. These practices have resulted in the infiltration of persistent contaminants into soils and groundwater aquifers, including heavy metals and industrial organic compounds, such as pesticides and coatings. Thus, many efforts have been made in the search for materials and devices to help remediate contaminated water. For example, various polymer-based membranes have been developed [

3,

4], yielding satisfactory results in water decontamination. Other developments have focused on fabricating nanostructured titanium oxide through different production methodologies [

5,

6] to employ this material in water decontamination due to its good optical and electrical properties. On the other hand, a wide range of metal ions such as iron [

7], nickel [

8], cobalt [

9], and manganese [

10] have been used as acceptor dopants into TiO

2; in this way, the TiO

2 photocatalytic activity was enhanced to varying extents. Likewise, metallic titanium doped with chemical elements of group 13 of the periodic table (B, Al, Ga, In and Tl – [

11,

12] has also been employed, equally with satisfactory results in water cleaning. The problem with most of these proposed developments is that the production methods for the purifying materials are complex to execute, due to the facilities required to manufacture the materials and the cost of the raw materials required to do so.

Photocatalysis is a natural phenomenon in which a substance uses the energy of natural light to remove pollutants. In the presence of air and light, the oxidation process is activated, decomposing the polluting organic substances that come into contact with the photocatalytic surface. Thus, TiO

2 has been widely recognized for its excellent photocatalytic properties [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. However, due to the large bandgap of TiO

2 of the order of 3.2 eV, the formation rate of reaction products per incident photon is very low. This feature severely limits TiO

2 applications since the UV percentage comprises only 5-8% of the solar energy. Several authors have reported that the addition of copper particles in TiO

2 can increase by several orders of magnitude and extend the absorption from the high energy range, the UV spectrum, into the visible, where the sun has its maximum energy output [

18,

19,

20,

21].

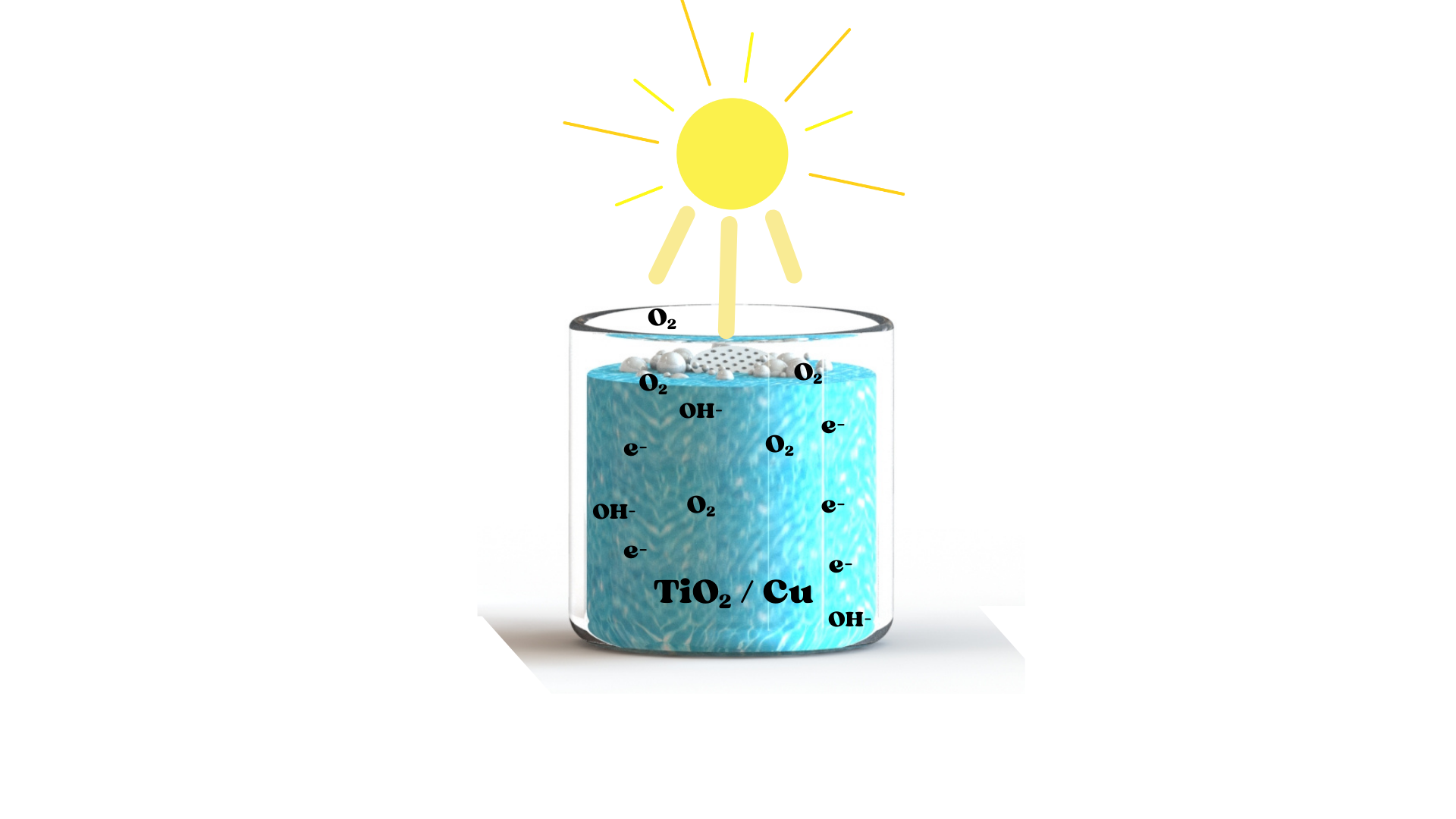

In the TiO

2/Cu mixture, copper acts as an electron scavenger, preventing the rapid recombination of electron-hole pairs and increasing the efficiency of the photocatalytic process. According to recent studies, adding 1% copper to TiO

2 has been shown to significantly improve its ability to break down organic compounds and remove heavy metals from wastewater. In addition, copper doping facilitates the production of reactive oxygen species, which are responsible for the oxidation of pollutants. Research on TiO₂/Cu composites has shown that copper incorporation extends semiconductor absorption into the visible spectrum and enhances photocatalytic efficiency by reducing electron-hole pair recombination [

22]. Also, a relevant study highlights the applications of TiO₂/Cu material in the removal of emerging pollutants and heavy metals, with a focus on efficiency and sustainability [

23]. With the resulting TiO

2/Cu material it is possible to direct this energy towards the triggering of chemical reactions of interest, such as reducing the presence of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi and others, in water. In this work, TiO

2/Cu materials were synthesized by employing powder techniques. Their impact on improving visible light absorption and pollutant decomposition efficiency was evaluated, highlighting their potential for sustainable wastewater treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

The powders used to prepare the photocatalytic material were TiO

2 (5 μm, 99.9%, Sigma-Aldrich) and copper nanoparticles (<100nm, 99.9%, SkySpring Nanomaterials, Inc.). Copper was added in amounts of 0 wt.% and 1wt.%. The TiO

2 + copper powders were ground in dry and mixed using a high-energy planetary ball mill (Retsch, PM 100, Germany). The grinding parameters used in the mixture were as follows: dry grinding for 6 hours at 300 rpm, using isopropyl alcohol as a control agent, and maintaining a ball weight to powder weight ratio of 10:1. Next, the grinding stage, the particle size distribution was determined using a Mastersizer 2000 equipment. The morphologic characteristics of the powders were analyzed by SEM (Jeol 6300, Japan). Structure crystalline was determined by XRD with a Bruker [Billerica, MA, USA] D8 ADVANCE diffractometer, scanning from 20 to 80° with a step size of 0.016° and a 10 s exposure time. The XRD patterns of the alloys were analyzed using X’Pert HighScore Plus (v2.2b) software. In order to measure the absorbance, a deuterium lamp with UV-Vis emission was used as light source. All the optical measurements were carried out with a compact CCD spectrometer (Thorlabs, CCS200, New Jersey) with a wavelength operational range from 200 to 1000 nm. Optical absorbance was measured as follows: firstly, the transmission spectrum from distilled water in a standard quartz cuvette (path length = 10mm) was measured and recorded as the reference; secondly, the transmission spectrum from a suspension of TiO

2 and TiO

2/Cu in distilled water in a quartz cuvette was measured and recorded; finally, based on the two previous measurements, optical absorbance was determined using the spectrometer software. The photocatalytic activity of pure and copper-doped TiO

2 nanopowders was studied by testing photocatalytic degradation of pond water contaminants under solar light for 150 min. A water sample was taken at each 30-minute time interval to determine the rate of decontamination of the water. Finally, microbiological analyses following Mexican standards [

24] were performed at 0 and 150 min to determine the effect of the photocatalytic material on water decontamination. The amount of powder added to the water was 0.1 wt. %.

3. Results

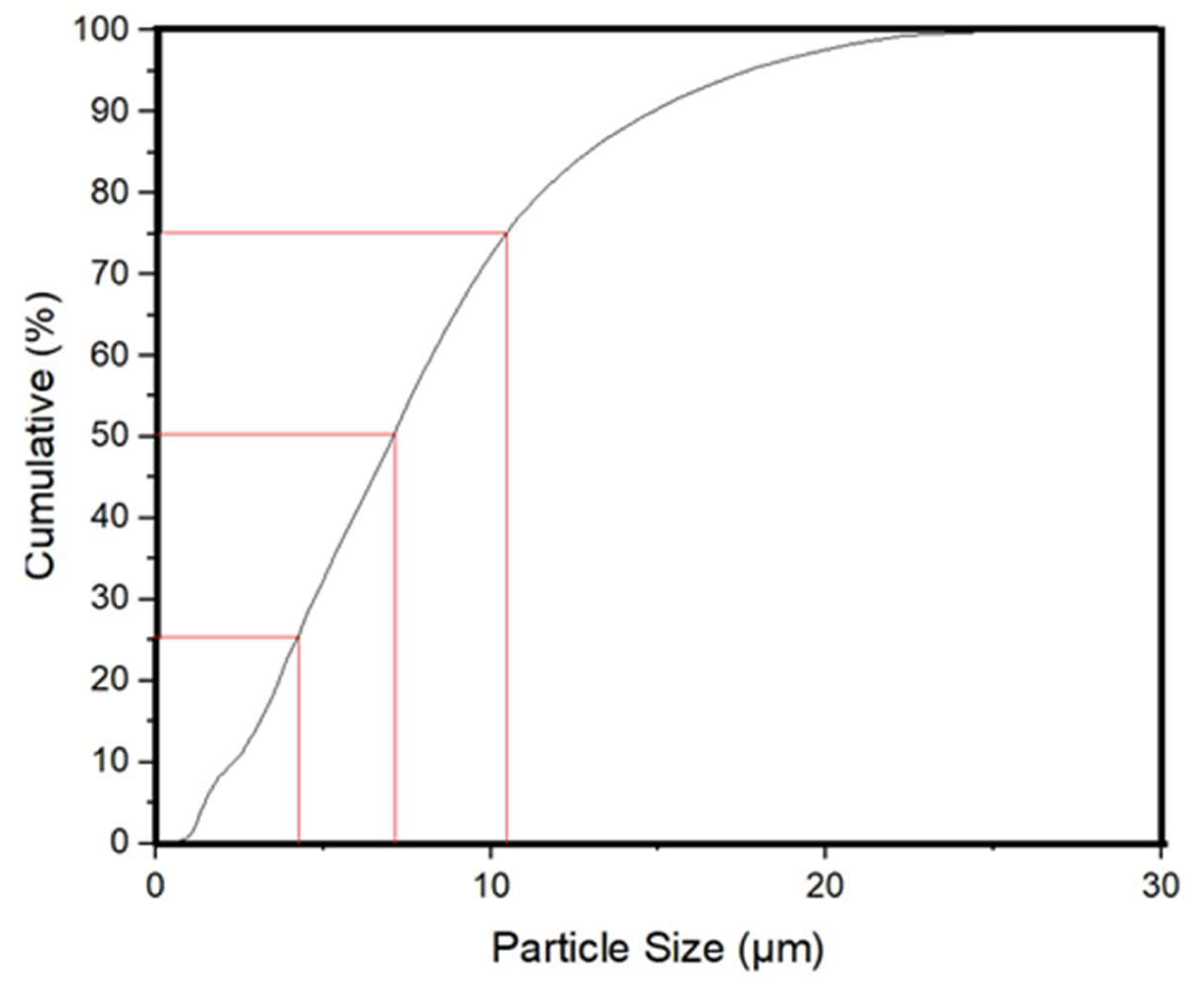

3.1. Powder Size

Figure 1 shows particle size distribution. This figure shows that the particle size in the powder ranges from 1 micron to approximately 11 microns. The curve shows that approximately 50 percent of the particles have sizes ranging from 1 to 7 microns. Meanwhile, the other 50 percent of the particles have sizes from 7 to 11 microns. The modal value is about 7 microns. Likewise, 25 percent of the particles are smaller than 4 microns, while another 25 percent exceed 10 microns. This distribution provides a favorable range of particle sizes, which enhances photocatalytic activity under sunlight due to the increased surface associated with size variation.

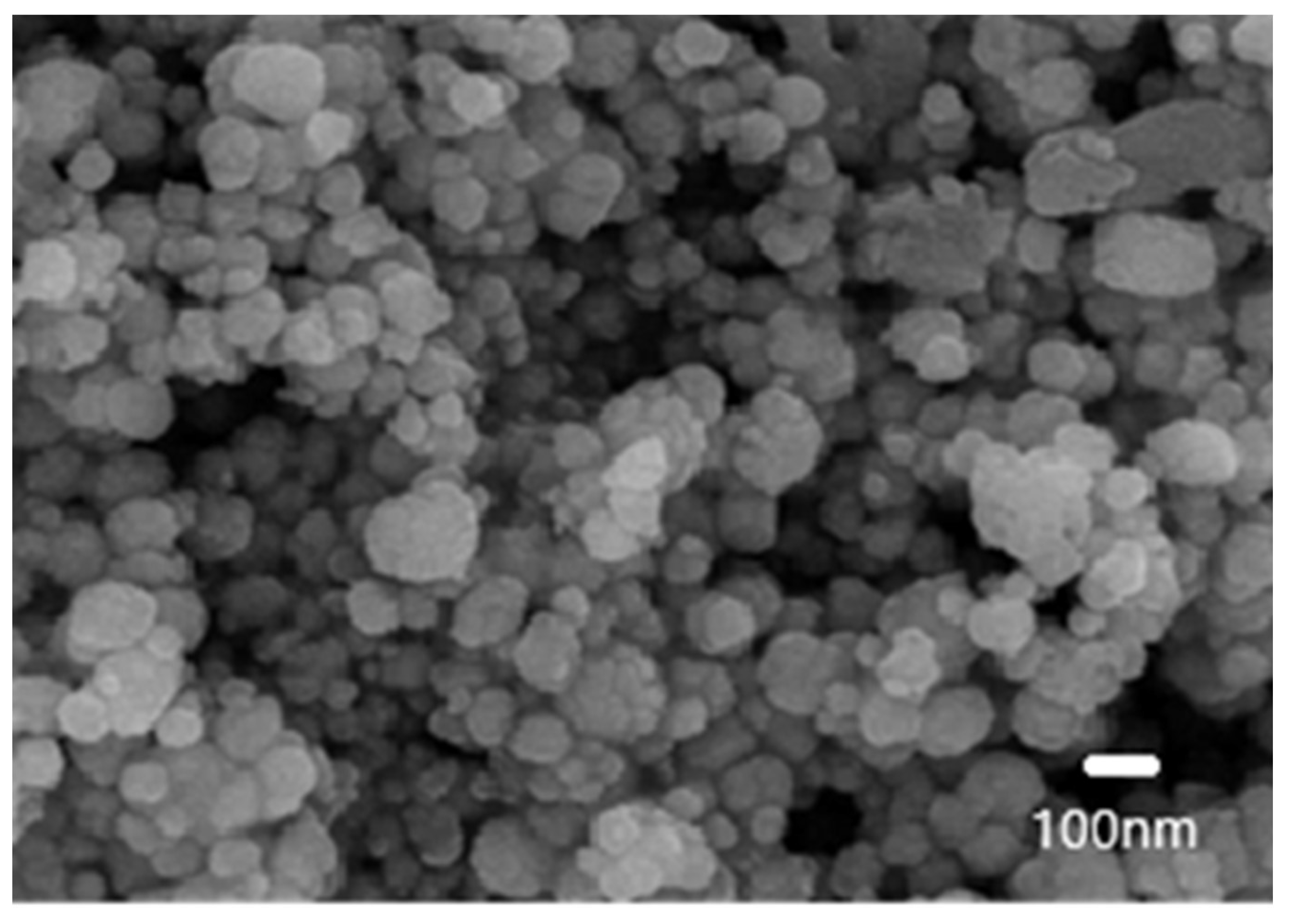

3.2. Powder Morphology

Figure 2 shows a SEM image of the milled powders, revealing that the particles exhibit a spherical-like structure with individual sizes slightly above 100 nanometers. However, the particles exhibit strong agglomeration due to their small size, as indicated by the granulometric analysis, which report sizes between 1 and 11 microns. Despite this, the fine particle size is expected to further enhance photocatalytic activity by increasing the interaction between TiO

2/Cu semiconductor with the solar radiation.

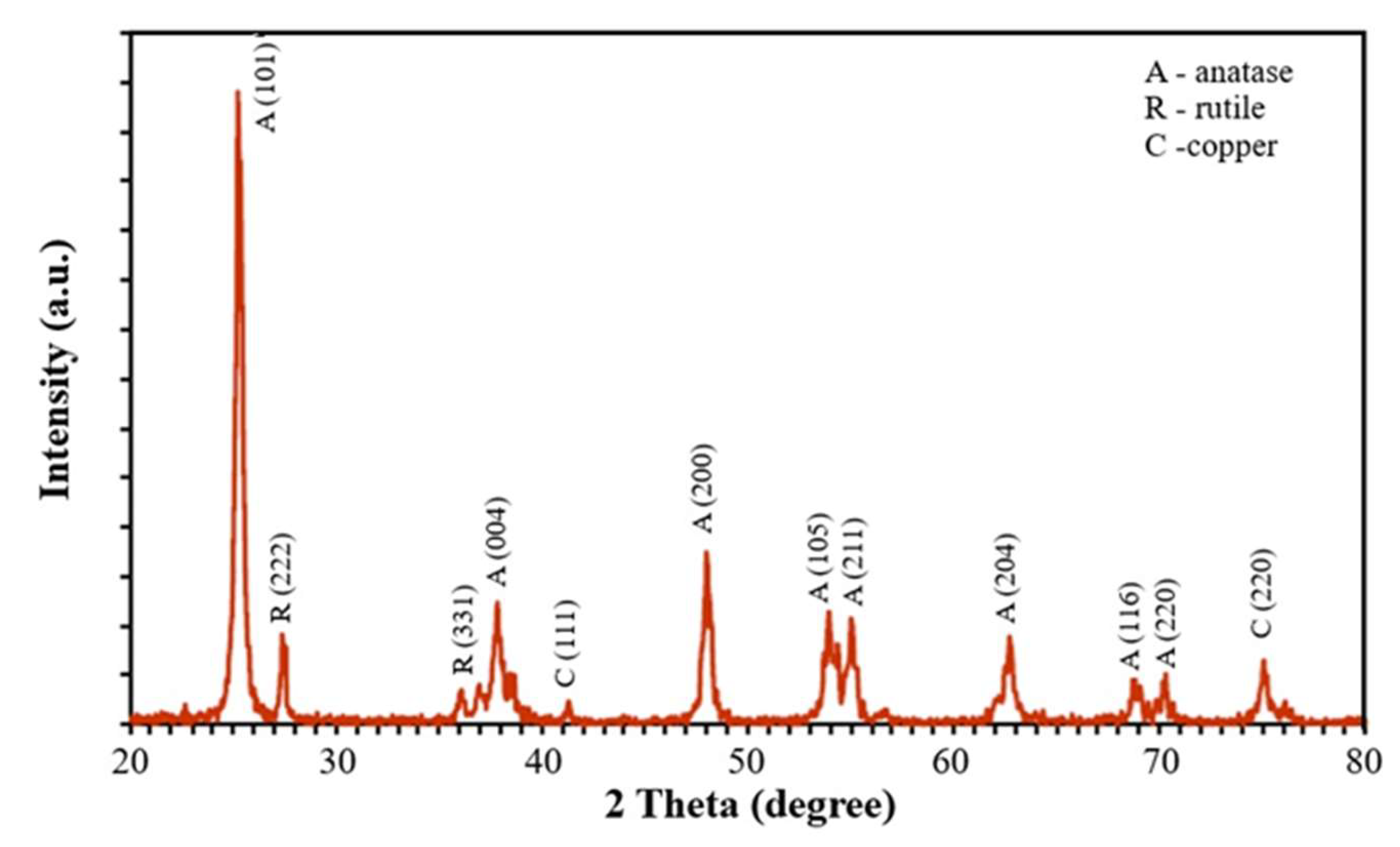

3.3. Structure

Figure 3 shows the X-ray diffraction pattern of the powder sample. The diffraction peaks correspond to the tetragonal crystalline structure of the anatase phase of TiO

2, which is the main component of the sample. The two peaks located at angles of 25.5° and 48.5° correspond to the most intense peaks of the aforementioned crystalline phase. Using the (101) plane peak of anatase and the Scherrer formula, the crystallite size was estimated to be 5.62 nm. The lattice parameters of the anatase were calculated as a = b = 0.377nm and c = 0.950nm. Some authors have documented that the photocatalytic activity of titanium oxide is better when it is in its anatase phase [

25]. On the other hand, in the diffraction pattern, two small peaks are observed at angles 2θ = 27.3 and 35.5, corresponding to the rutile phase of TiO

2. Peaks at 43° and 74° are attributed to the (111) and (220) planes of copper, indicating the presence of its cubic structure.

3.4. Photocatalytic Activity

To evaluate the photocatalytic activity of copper-doped TiO

2, a degradation experiment using methylene blue (MB) was conducted under sunlight irradiation. Aliquots of the treated solution were taken every 30 minutes throughout the reaction, up to 150 minutes;

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show how the absorbance intensity decreases with reaction time. It is important to mention that the photoluminescent signal is directly related to the speed of recombination of the photogenerated charges, the electron-hole pairs; consequently, a lower photocatalytic response is expected from the pure TiO

2 sample and a higher response for the copper-doped TiO

2 sample. Thus,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the photocatalytic activity of as-prepared pure and copper-doped TiO

2 samples toward the MB solution at various time intervals for sun irradiation, respectively. The absorption intensity decreases gradually with the increase in time, indicating that the MB suffered degradation during the photocatalytic reaction under sunlight irradiation. From the absorbance results in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, it is observed that pure TiO

2 nanoparticles show a low decomposition rate when compared to the decomposition rate with copper-doped TiO

2 nanoparticles. Cu-ions play a significant role in the catalytic process. The photocatalytic activity of copper-doped TiO

2 has been enhanced due to the improvement in the formation of oxygen vacancies. These oxygen vacancies are directly involved in the photocatalysis processes. Sun irradiations provide enough energy to excite the electrons of copper-doped TiO

2 nanoparticles and generates more electron–hole pairs, which improve photocatalytic activity. It can capture the photo-generated holes (h+) and transform them into OH radicals, the main reactive species for the decomposition of organic molecules. Therefore, the enhanced property of copper-doped TiO

2 nanoparticles to generate OH radicals leads to improved photocatalytic degradation performance. Hence, the copper-doped TiO

2 nanoparticles show increased photocatalytic activity under sun irradiation. The increased photocatalytic activity of copper-doped TiO

2 nanoparticles may be attributed to their larger crystalline size and more ordered crystalline phase.

To better illustrate the effect of Cu on TiO

2 to clean water,

Figure 6 is constructed. This figure shows optical absorbance from water samples with TiO

2 and TiO

2/Cu to study their photodegradation performance at different times. As can be seen, at 0 minutes, the samples exhibited an absorption peak at 655 nm. Notably, the sample with TiO

2/Cu showed higher optical absorbance, which enhances photocatalytic activity. A blue shift was observed in both samples, attributed to the reduction in particle sizes at the nanoscale [

26] and linked to pollutant decomposition. Here, upon being doped with Cu, the band edge of this adsorption shifts toward long wavelength, which indicates the band gap is narrowed by doping with Cu. The presence of the dopant brought about a shift of the absorption edge to the visible light region, and intense absorption was observed. This intense absorption of visible light can be attributed to the following aspects: (a) the Cu doping introduced impurity states below the conduction band minimum, leading to the band gap reduction, and (b) the excitations between O 2p states and Ti 3d states through Cu 3d states. Additionally, charge transfer bands can provide insight into the environment and nature of Cu

2+ ions. Thus, according to the literature [

27,

28,

29,

30], bands describing the Cu

2+ species can be located in several regions. The absorption bands at 600 nm are attributed to the

2Eg→

2T2g transition of Cu

2+ located in the distorted or perfect octahedral symmetry.

3.5. Reaction Rate

The reaction of photocatalytic degradation of dye with respect to reaction time follows first-order rate kinetics, which was confirmed by the linear transforms of Eq. (1):

where A

0 is the absorbance value of MB at t = 0 and A

t is the absorbance of MB at different irradiation times.

Figure 7 shows the plot of the decomposition rate of MB using copper-doped TiO

2 nanoparticles as a function of irradiation time. The absorbance equation is a fundamental formula used to quantify the amount of light absorbed by a sample, i.e., it is the measure of a substance’s ability to absorb light at a specific wavelength. Thus, the decrease in the optical absorbance shown in

Figure 7 demonstrates the efficiency of the degradation process.

Based on the data from the samples exposed to sunlight, an average absorption was calculated by comparing the initial measurement (0 minutes) with the fifth measurement (150 minutes). The results showed that the TiO2 tests absorbed 39.18% of impurities, while the TiO2/Cu tests reached 60.52%. This confirms the hypothesis that copper doping significantly improves water decontamination efficiency. Absorbance refers to the capacity of these materials to absorb light, especially in the wavelength range corresponding to ultraviolet (UV) or visible radiation.

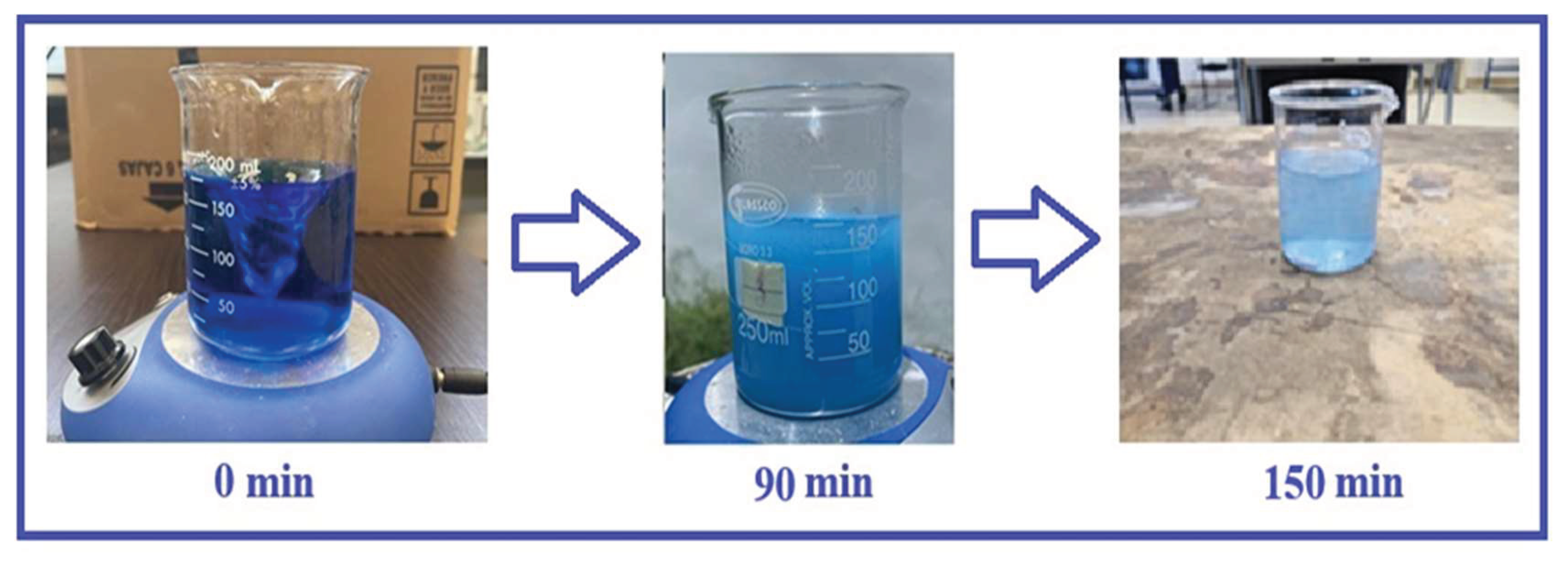

Figure 8 shows images taken at different treatment times of water exposed to sunlight in the presence of TiO

2/Cu powder. This figure shows that as exposure time increases, the blue color of the water tends to degrade, which is indicative of the purification of the water as observed in the absorbance results.

3.6. Photocatalytic Antibacterial Activity

Table 1 shows the results of microbiological analyses performed on contaminated water 150 minutes after exposure to solar radiation, with the addition of 1% TiO

2/Cu. The results show a high effectiveness of the treatment, reducing the amount of total coliforms by 87% and fecal coliforms by more than 93%. These data demonstrate the photocatalytic material’s high effectiveness in improving water quality.

While the addition of copper reduces the overall band gap, the resulting trap sites may also acts as recombination centers. Copper cations are the key species responsible for altering the sample’s optical properties, as evidenced by absorption spectrum shown in

Figure 6. It is suggested that the existence of Cu improves photocatalytic efficiency. The copper cation acts as a trapping sink for the excited electrons. Thus, on visible light irradiation, the electron-hole pair generated on the TiO

2 surface reacts with the oxygen and water adsorbed on the catalyst surface to produce superoxide radicals and holes, respectively. These reactive oxygen species interact with the bacterial cell wall, resulting in membrane disruption and outflow of intracellular materials, resulting in cell lysis (

Table 1). In addition to this, the reactive oxygen species produced can interact with the sugar phosphate groups present in the DNA of the bacteria to cause gene alteration. Further altering the protein expression responsible for cellular functioning leads to cell damage [

31,

32].

4. Conclusions

In the present work, a visible-light-active semiconductor material, i.e., TiO2 doped with 1wt.% Cu, was successfully synthesized using the powder method. The introduction of a small percentage of Cu inside the TiO2 lattice has led to an improved cationic doped TiO2 sample. XRD result confirmed that the TiO2 is mainly present in its anatase crystalline structure. The presence of copper contributed to the enhanced stability of the anatase phase and also exhibited improved visible light antimicrobial efficiency. The size and morphological characteristics of the processed powders indicate that the powder is agglomerated due to its very small size and present round shapes. The photocatalytic activity values clearly indicate that Surface Cu2+ may act as the photoactive species, leading to improved photoactivity with respect to undoped TiO2 samples. The enhanced photocatalytic degradation performance for Cu-doped TiO2 can be attributed to the crystallinity and low recombination rate of photogenerated electron-hole pairs. Copper-doped TiO2 nanoparticles were effective in the decomposition of pollutants in wastewater. So, through this research, it was established that modifying TiO₂ with Cu is a promising strategy for industrial water treatment, providing an innovative and economical solution in the field of water decontamination.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, DRP-H, DYR-S and ER-R; methodology, DRP-H, DYR-S, MTM-S and JAC-R; software, MTM-S and JAR-G; validation, MTM-S, CAC-A and ER-R; formal analysis, DRP-H, DYR-S, MTM-S and JAC-R; investigation, DRP-H, DYR-S, MTM-S and JAC-R; re-sources, CAC-A and ER-R; data curation, DRP-H, DYR-S, MTM-S and JAC-R; writing—original draft preparation, DRP-H, DYR-S, MTM-S; writing—review and editing, DRP-H, DYR-S, CAC-A and ER-R; visualization, MTM-S, CAC-A and ER-R; supervision, MTM-S and CAC-A; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no interests or personal relationships that could influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Cu |

Copper |

| TiO2

|

Titanium |

| XRD |

X-ray diffraction |

| SEM |

Scanning electron microscopy |

| nm |

nanometeres |

| UV |

Ultraviolet |

| MB |

Methyl bleu |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic acid |

References

- A. Maceira, ¿Qué es el agua? (What is water), 2020. https://www.iagua.es/respuestas/que-es-agua (last accessed April 29, 2025).

- C. Nunez, La contaminación del agua constituye una crisis mundial creciente. Esto es lo que hay que saber (Water pollution is a growing global crisis. Here’s what you need to know), National Geographic, 2024. https://www.nationalgeographic.es/medio-ambiente/contaminacion-del-agua (last accessed April 29, 2025).

- U.S. Provisional Patent Application No. 62/866,459 filed June 25, 2019.

- Gloria Sandoval Flores, Mexican Patent No. 418558, 18 Dec 2019.

- Salvador Castillo Cervantes, Mexican Patent No. 349068, June 28, 2017.

- César Cutberto Leyva Porras, Mexican Patent No. 370470, November 12, 2019.

- R. Su, R. Bechstein, J. Kibsgaard, R.T. Vang, F. Besenbacher, High-quality Fe-doped TiO2 films with superior visible-light performance, J. Mater. Chem., 2012, 22, 23755–23758. [CrossRef]

- D.H. Kim, K.S. Lee, Y.S. Kim, Y.C. Chung, S. J. Kim, Photocatalytic Activity of Ni 8 wt%-Doped TiO2 Photocatalyst Synthesized by Mechanical Alloying Under Visible Light, J. Am. Ceram. Soc., 2006, 89, 515–518. [CrossRef]

- Z.H. Yuan, J.H. Jia, L. Zhang, Enhanced Visible Light Photocatalytic Activity of Ag and Zn Doped and Codoped TiO2 Nanoparticles, Mater. Chem. Phys, 2002, 73, 323–326. [CrossRef]

- G.R. Deng, X.H. Xia, M.L. Guo, Y. Gao, G. Shao, Mn-doped TiO2 nanopowders with remarkable visible light photocatalytic activity, Mater. Lett., 2011, 65, 2051–2054. [CrossRef]

- Diego Venegas Yazigi, Chilean Patent No. 201702281, September 8, 2017.

- Gema Luna Sanguino, Spanish Patent No. 2 922 424, February 10, 2023.

- S. Reda, M. Khairy, M. Mousa, Photocatalytic activity of nitrogen and copper doped TiO2 nanoparticles prepared by microwaveassisted sol-gel process, Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 86–95. [CrossRef]

- C. Thambiliyagodage, S. Mirihana, Photocatalytic activity of Fe and Cu co-doped TiO2 nanoparticles under visible light, J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2021, 99, 109–121. [CrossRef]

- C. Thambiliyagodage, L. Usgodaarachchi, Photocatalytic activity of N, Fe and Cu co-doped TiO2 nanoparticles under sunlight. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 4, 100186. [CrossRef]

- C. Cheng, W.H. Fang, R. Long, O.V. Prezhdo, Water splitting with a single-atom Cu/TiO2 photocatalyst: Atomistic origin of high efficiency and proposed enhancement by spin selection. J. Am. Chem. Sos. 2021, 1, 550–559. [CrossRef]

- T. Cˇižmar, I. Panžic’, I. Capan, A. Gajovic’, Nanostructured TiO2 photocatalyst modified with Cu for improved imidacloprid degradation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 569, 151026. [CrossRef]

- M.M. Abbas, M. Rasheed, Solid State Reaction Synthesis and Characterization of Cu doped TiO2 Nanomaterials, J. Phys. Conf. Ser., 2021, 1795, 012059-012068. [CrossRef]

- R. Ahmadias, G. Moussavi, S. Shekoohiyan, F. Razavian, Synthesis of Cu-Doped TiO2 Nanocatalyst for the Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation and Mineralization of Gabapentin under UVA/LED Irradiation: Characterization and Photocatalytic Activity, Catal, 2022, 12, 1310-1327. [CrossRef]

- M.A. Behnajady, H. Taba, N. Modirshahla, M. Shokri, Photocatalytic activity of Cu doped TiO2 nanoparticles and comparison of two main doping procedures, Nanomicro Lett., 2013, 8, 345–348. [CrossRef]

- Y. Mingmongkol, D.T.T. Trinh, P. Phuinthiang, D. Channei, K. Ratananikom, A. Nakaruk, W. Khanitchaidecha, Enhanced Photocatalytic and Photokilling Activities of Cu-Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles, Nano, 2022, 12, 1198-1209. [CrossRef]

- X. Li, D. Zhang, S. Chen, H. Zhang, Z. Sun, S. Huang, X. Yin, Dye-sensitized Solar Cells with Higher J sc by Using Polyvinylidene Fluoride Membrane Counter Electrodes, Nano Micro. Lett., 2011, 3, 195–199.

- A. Di Paola, M. Bellardita, L. Palmisano, Brookite, the least known TiO2 photocatalyst. Cat., 2013, 3, 36-73. [CrossRef]

- Microbiological test methods, NOM-210-SSA1, 2014.

- A.S. Teddy, T. Iryna, I. Monica, E. Cristian, R. Daniela, C. Culita, A. Mihai, R. Aurelian, C. Galca, TiO2 Phase Ratio’s Contribution to the Photocatalytic Activity, ACS Omega, 2023, 8, 41664−41673. [CrossRef]

- L.V. Trandafilović, D.J. Jovanović, X. Zhang, S. Ptasińska, and M.D. Dramićanin, Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue and methyl orange by ZnO:Eu nanoparticles, Appl. Catal. B Environ., 2017, 203, 740–752. [CrossRef]

- G. Jeon, J. Chaung, Preparationand characterization of silica-supported cop-per catalysts for the dehydrogenation of cyclo-hexanol to cyclohexanone, Appl. Catal., 1994, 115, 29-44. [CrossRef]

- H. Praliaud, S. Mikhailenko, Z. Chajar, M. Primet, Surface and bulk properties of Cu–ZSM-5 and Cu/Al2O3 solids during redox treatments. Correlation with the selective reduction of nitric oxide by hydrocarbons, Appl. Catal. B: Environ., 1998, 6, 359-374. [CrossRef]

- L. Chen, T. Horiuchi, T. Osaki, T. Mori, Catalytic selective reduction of NO with propylene over Cu-Al2O3 catalysts: influence of catalyst preparation method, Appl. Catal. B: Environ., 1999, 23, 259-269. [CrossRef]

- S. Velu, K. Suzuki, M. Okazaki, M.P. Kapoor, T. Osaki, F.J. Ohashi, Oxidative Steam Reforming of Methanol over CuZnAl(Zr)-Oxide Catalysts for the Selective Production of Hydrogen for Fuel Cells: Catalyst Characterization and Performance Evaluation, J. Catal., 2000, 194, 373384. [CrossRef]

- T. Verdier, M. Coutand, A. Bertron, C. Roques, Antibacterial activity of TiO2 photocatalyst alone or in coatings on E. coli: the influence of methodological aspects, Coatings 2014, 4, 670-686. [CrossRef]

- P. Ganguly, C. Byrne, A. Breen, S.C. Pillai, Antimicrobial activity of photocatalysts: fundamentals, mechanisms, kinetics and recent advances. Applied Catalysis B: Environ., 2018, 225, 51-75. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).