1. Introduction

An emulsion is a system comprised of two immiscible phases and an interfacial stabilizer, called emulsifier or surfactant. Emulsions emerge during the production of hydrocarbons, by the combined action of natural surfactants present in the crude oil and energetic fluid agitation, induced by pumping or flow through porous media in the reservoir [

1,

2]. Traditionally, emulsions are considered undesirable because emulsified crude oil affects downstream operations such as multiphase flow separation and product quality [

3]. Moreover, water-in-oil (W/O) emulsion generation have been reported to hinder recovery as the dispersed water phase in oil, increases the continuous (oil) viscosity [

4]. However, in recent years, emulsion analysis has been linked to beneficial mechanisms in enhanced oil recovery processes because these dispersions can function as mobility control or conformance agents [

5,

6].

Some authors have focused on the relationship between demulsification kinetics and the stability of crude oil/brine interfaces [

7]. This idea addresses the strengthening of the fluid/fluid interactions that give rise to better connectivity of oil ganglia in porous media and therefore higher oil recovery. Macro-emulsions are thermodynamically unstable but can exhibit kinetic stability because of the competition of opposing forces acting over the dispersed phase. These forces can be attractive, like Van der Waals; or repulsive, like steric and electrostatic interactions [

8]. The most important Van der Waals attractions in emulsions are the London dispersion forces that arise from charge fluctuations. Then, in the absence of emulsifiers, flocculation and demulsification should occur spontaneously and rapidly. Since this does not happen, repulsive forces are evidently acting as well. When charged drops in an emulsion approach, their double layers overlap and repulsion occurs. The extension of the double layer depends on the electrolyte concentration and its valence, specifically, a decrease in concentration and a low valence will produce a more extended double layer and a higher repulsion. Finally, steric repulsion arises from the adsorption of nonionic surfactants and polymers at the interface of the liquids. The thickness of hydrophilic chains produces repulsion because of an unfavorable mixing of the chains [

9].

Emulsion breakdown involves three steps: sedimentation or creaming, flocculation, and coalescence, before separation takes place [

10]. Sedimentation occurs in W/O emulsions when water droplets settle down because their density is higher than that of the crude oil (provided API gravity is higher than 10, namely for heavy oil or less dense fluids). Gravitational sedimentation is approximately governed by Stokes’ law, which allows calculating the settling velocity for a solid sphere in a viscous fluid at a small Reynolds number [

11]. On the other hand, creaming is a process analogous to sedimentation that occurs in Oil-in-Water (O/W) emulsions when oil drops rise because of their lower density compared to that of the continuous aqueous phase. Flocculation or aggregation is often the first stage in emulsion breakage. During flocculation, dispersed phase drops tend to clump together forming aggregates. Drops, despite getting closer together, even creating junctures at some contact points, do not necessarily lose their identity [

12]. However, during coalescence, droplets of the dispersed phase exchange mass and release interfacial energy eventually forming larger drops. This process is irreversible, attaining a lower free-energy state and leading to a decrease in the number of droplets [

13].

Several factors influence emulsion stability, including phase density and viscosity, crude oil and brine composition, interface aging and consequently its mechanical properties, volume phase ratio, droplet size, and temperature, among others [

14].

Emulsion stability refers to the ability of emulsions to remain unchanged over time, in terms of drop size distribution. Stability is influenced by the constituents of the phases and the formation conditions. Some properties such as dispersed phase concentration and drop size, interface charge and rheology, among others, can be used to assess the stability of emulsions [

15].

Microscopy allows the assessment of the droplet-size distribution (DSD), as to ascertain relative emulsion stability by tracking DSD over time. Flocculation can be determined when droplets get closer to each other forming aggregates. While, on the other hand, a non-flocculated emulsion will show homogenously distributed droplets of small size [

16]. Even while microscopy is a simple, intuitive, fast, and inexpensive technique for analyzing the emulsions qualitatively; the reproducibility problems of the quantitative results make it necessary to use alternative techniques.

After the flocculation and coalescence steps, some methods rely on phase separation measurements. This generally consists of measuring the amount of resolved phase from emulsions, either naturally or by external forcing. According to this technique, the smaller the dispersed phase-resolved volume, the more stable the emulsion is [

17]. Even when this technique provides a simple strategy for figuring out emulsion stability, the demulsification process is studied as a whole, that is, it is not always possible to discriminate the occurrence of different demulsification steps. Also, this technique is not adequate for tight-stiff emulsions or emulsions with a not sharply defined interface [

18].

Despite extensive research on emulsion stability, only a few research works quantitatively describe how temperature and salinity affect demulsification kinetics. In addition, this type of study is one of the first to report for this variety of Amazonian crudes. Fluid/fluid interactions depend on both the characteristics of the brine and the crude oil. No such studies have been reported on Ecuadorian crude oil samples in the available literature. The objective of this work is to ascertain the influence of temperature, within a range possible under our experimental conditions, and low versus high salinity conditions on the relative stability of W/O macroemulsions formulated with an Ecuadorian crude oil. Since this type of Amazonian crude oils are often exposed to low-ionic strength water, we wanted to determine if this condition could increase emulsion stability as opposed to an ionic strength more similar to seawater. The intention, however, was not to conduct a salinity scan. Both DSD, via Time-Domain Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (TD-NMR); and phase separation, via bottle test, were conducted as proxies of two dominant stages that reflect emulsion stability. To understand interfacial mechanisms contributing to emulsion stability, interfacial tension and dilatational interfacial rheology were measured using a pendant-drop tensiometer with an oscillating drop generator (ODG).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Crude Oil

A representative sample of a medium crude oil taken from the Sacha Oilfield, in the Ecuadorian Amazon Basin, was used in all experiments. This sample was characterized by density, viscosity and percentage of asphaltenes measurements using the following equipment and conditions: a) density with an Anton Paar DMA 4500M Density meter at 25 °C; b) viscosity with an AR-G2 Magnetic Bearing Rheometer (TA Instruments), executing a frequency sweep from 0.05 to 500 Hz at 25 °C; c) the percentage of asphaltenes by using the ASTM D6560 standard, based on the insolubility of these molecules in heptane. Results of the crude oil characterization are summarized in

Table 1.

2.2. Aqueous Phase

Deionized water and a mixture of different analytical grade salts, namely

,

,

, and

, were used to prepare the aqueous phases. The proportions of the salts were selected to emulate the Sacha Oilfield formation water composition, as the mother solution, corresponding to what was labelled as 100% formation water (FW). A one-hundred-fold dilution of the mother solution with DI water was labelled as 1% FW. The density of the solutions was measured using an Anton Paar Density meter DMA 4500M at 25 ℃. The pH of the solutions was measured by using a VWR B10P (SympHony) pH meter. The results of aqueous phase characterization are summarized in

Table 2.

2.3. Emulsions Preparation

Emulsions were prepared by mixing 75 ml of crude oil with 25 ml of brine so that the volumetric ratio of phases is 3:1 in a homogenizer UltraTurrax T25 Basic (IKA). Mixing was conducted at an agitation speed of 8 000 rpm for 5 min. The volumetric fluid ratio was selected based on our extensive experience with other crude oils leading to W/O emulsions, The fluid shearting procedure was also based on previous experience in our laboratory. The stirring speed and time selected from experience were adequate to effectively produce a dispersion that would not break up to rapidly while also avoiding the generation of tight emulsions. No exogenous emulsifiers were used.

2.4. Bottle Tests Measurements

This technique focuses on the analysis of the phase separation step. The bottle tests were performed following the ASTM D1401-02 standard, corresponding to the water and oil separability test. A special separability apparatus was used, consisting of a thermal bath and a mixer. Once the emulsions were prepared and the temperature of interest was selected, the volume of resolved water (water volume at the bottom of the bottle) was recorded every 5 min for one hour, as specified by the norm. Both crude oil and brines were fresh for each measurement to avoid the effects of interfacial aging and crude oil oxidation on the results.

2.5. Interfacial Tension (IFT) Measurements

A pendant drop tensiometer (OCA 15, Future Digital Scientific Corporation), set up with a high-speed camera, was used to measure IFT. The solution of interest was placed in a quartz cuvette after being filtered with a 0.2 mm SFCA filter. Then, a drop of crude oil was formed using a top to bottom geometry (J-shaped needle 18, ID: 1.27 mm). The IFT was measured every hour immediately after drop formation. To avoid the effects of evaporation on the brine concentration, the cuvette was sealed with mineral oil. The Worthington number (Wo) was used as a validation criterion for the measurements in this technique, being Wo=1 the ideal case:

where ∆ρ is the density difference, g is the gravitational acceleration constant,

Vd is the drop volume, γ is the equilibrium IFT, and

Dn is the internal diameter of the syringe.

The oil droplets volume was 35 μL for all measurements, with which the Worthington numbers ranged between 0.5 and 0.6, values that provided repeatable measurements

2.6. Interfacial Dilatational Rheology Measurements

The same tensiometer setup used for IFT measurements, was configured with an oscillating drop generator (ODG, Future Digital Scientific Corporation). For oscillatory measurements, ten cycles were recorded at a capture rate of ten frames per second. The interfacial viscoelasticity (IFVE) measurements were extracted from the analysis of the Fourier transforms of the drop area and the IFT harmonics. The relaxation of the oil droplet, induced by the decrease in its capillary pressure, had an impact on the quality of the oscillations. To reduce the effects of the IFT decay on the harmonics baseline, short periods (10 s) and suitable deformation amplitudes were selected. To define the linear viscoelastic region, the elastic and viscous modulus of the crude oil/diluted formation brine system were measured after 1h of aging at a frequency of 0.1 Hz. The experiment was repeated with different drops, changing only the amplitude of the deformations (strain), between 2 and 6% of the original area of the drop. After defining the frequency and amplitude of the deformation, the viscoelasticity of the system was reported every hour during an interval of eight hours, at temperatures of 25, 40, and 54 °C. Although the mineral oil seal successfully controlled the evaporation of the brines, when temperatures higher than those reported were attempted, the excessive thermal agitation of the system, due to the proximity of the boiling point of water, considerably deteriorated the droplet profile and prevented further measurements.

2.7. Shear Rheology Measurements

An ARG2 Magnetic Bearing Rheometer from TA Instruments was used to measure the crude oil shear viscosity as a function of temperature. A cone-and-plate fixture, 40-mm diameter and 2° cone, was used. For each measurement, 1 ml of crude oil was placed on the plate forming a 400 μm thickness film. Frequency sweeps ranged from 0.05 to 500 Hz. Temperature ranged from 25 to 65 °C in 10 °C increments.

2.8. Pulsed Field Gradient Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (PFG-NMR) Measurements

This technique can be used to determine drop size in a non-invasively fashion because it does not require pressing the sample between layers, like in microscopy, or diluting the crude oil required for light scattering techniques. The instrument used was a Bruker minispec mq-20 TD-NMR Spectrometer. The processing software assumes that the droplets distribution of W/O emulsions is log-normal. Experimental data showed that this mathematical function is the most suitable to describe the particle size distribution of these systems. Samples tubes were always filled up to 1 cm before any measurement. A calibration was performed with doped water samples (0.5% m/m CuSO4.5H2O). Measurements were made at 25 °C with field gradients of 2 T/m and δ values of 0.3 ms.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Salinity Effect

3.1.1. Emulsions Generation

Emulsions generated by mixing crude oil and the selected brines were effectively created without the addition of external emulsifiers. Polar organic substances, namely asphaltenes, resins, and organics acids in a crude oil, are known to exhibit amphiphilic properties and therefore act as surfactants [

19]. The type of emulsion generated depends on the nature of the surfactants, the volumetric phase ratio, and other thermodynamic properties [

20].

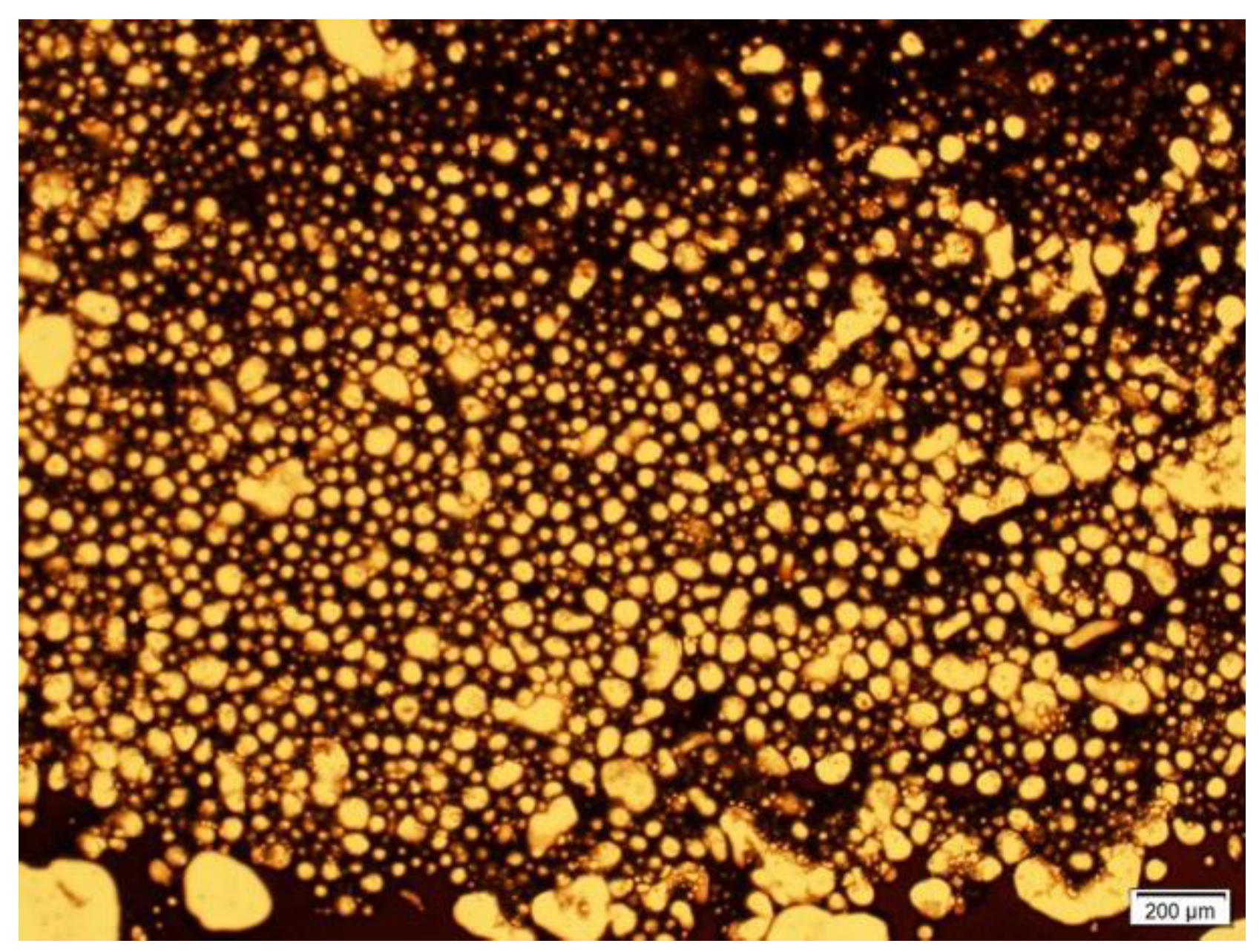

Figure 1 shows that emulsions generated corresponded to W/O microemulsions with no significant presence of double emulsions.

3.1.2. Bottle Tests

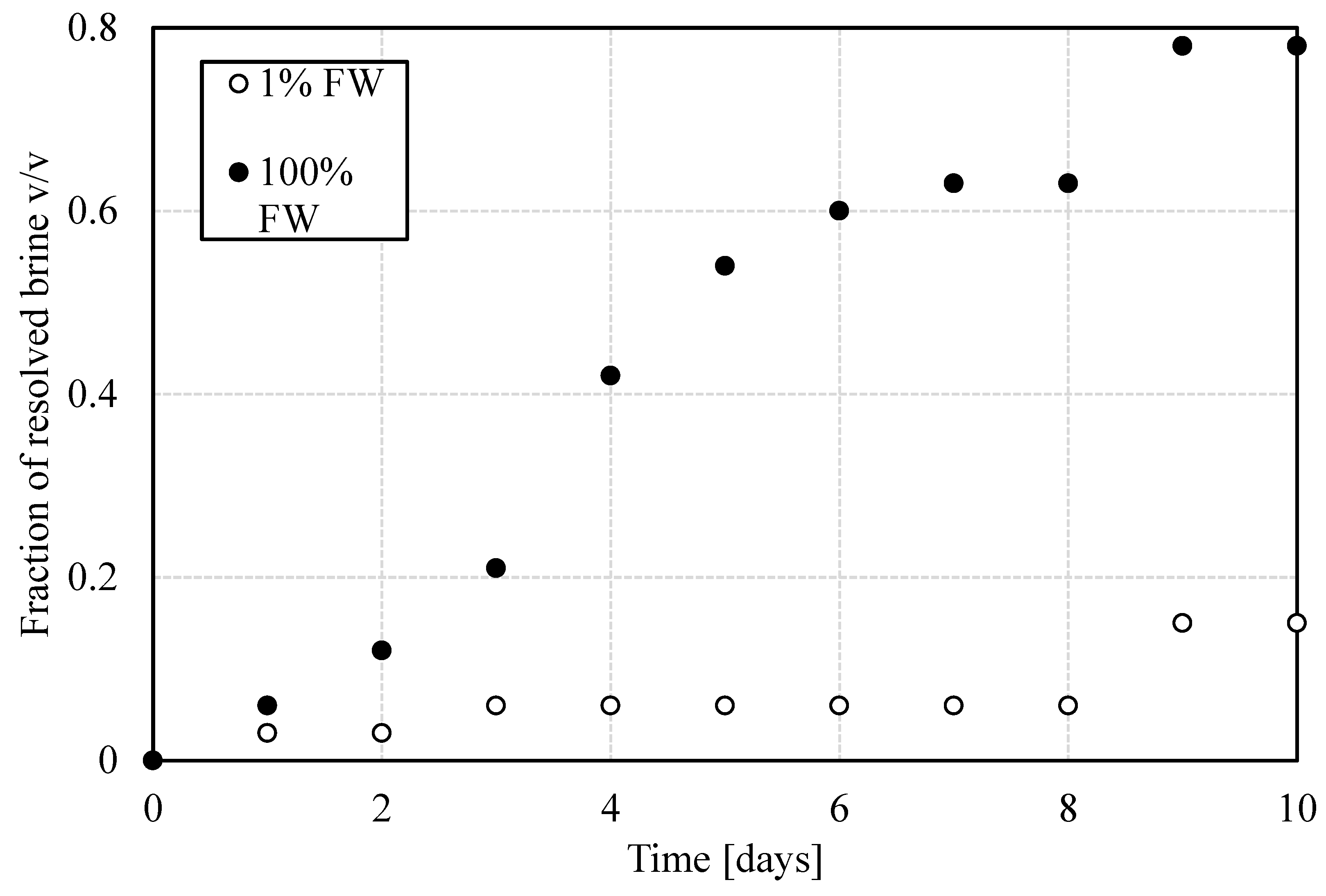

The bottle tests provide a first estimate of the stability of the emulsions. According to this test, the more stable an emulsion is, the fewer phases will be resolved over time. In the context of emulsions, resolving a phase implies its phase separation from the dispersion. As can be seen in

Figure 2, reducing the salinity of the formation water one hundred-fold led to more stable emulsions. Also form

Figure 2, it is evidenced that the phase-separation process initiates during the first day after preparing the emulsions. However, while water resolution can be detected after one day, the total for the high-salinity aqueous phase approaches 80% v/v, in contrast to less than 20% v/v for the 1% salinity aqueous phase. This relative stability difference is significant enough to infer that mechanisms such as coalescence might be hindered by W/O interfacial strengthening. Bottle tests are practical and ideal for speedy analysis, but their simplicity limits the unveiling of processes leading to the emulsion’s breakdown. For this reason, these measurements were complemented with an analysis of droplet-size distribution and interfacial properties to quantify the influence of salinity differences in the different demulsification steps.

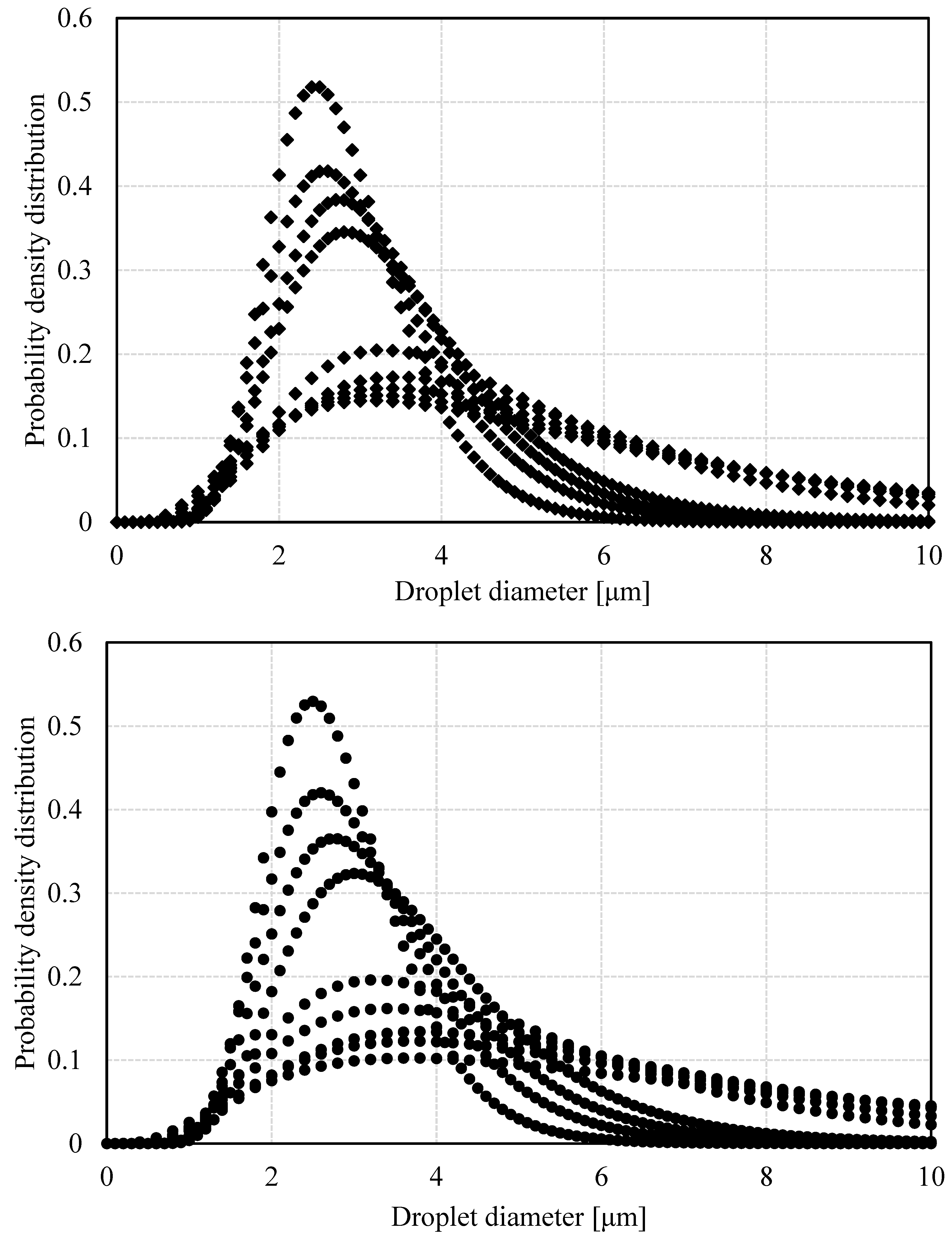

3.1.3. DSD by PFG-NMR

When using PFG-NMR to estimate DSD through restrictive diffusion, the analysis software assumes that the distribution is Gaussian, which has been reported to be an ideal model for describing experimental observations [

21]. For the respective analysis, the volumetric average radius and its respective standard deviation have been recorded as estimators of the size of the drops and their degree of size dispersion. At the time of emulsions formation, there is a narrow distribution of water droplets whose average radius is roughly 3 µm. During the first hour, there is a decrease in the average droplet radius, possibly due to the rapid initial settling of large droplets, which contribute considerably to the average radius. After this initial sedimentation, a tendency towards an increase in droplet size takes place (

Figure 3), which could be attributed to the simultaneous occurrence of flocculation and coalescence. Regardless of salinity, both the average droplet radius and the width of the distribution grow continuously. Notwithstanding, it can be observed that these growth rates are not constant since their values are higher in the first hours of demulsification. Additionally, the drops are slightly smaller when the emulsions were formed with low salinity brine, which is associated with greater emulsion stability.

3.1.4. Interfacial Properties

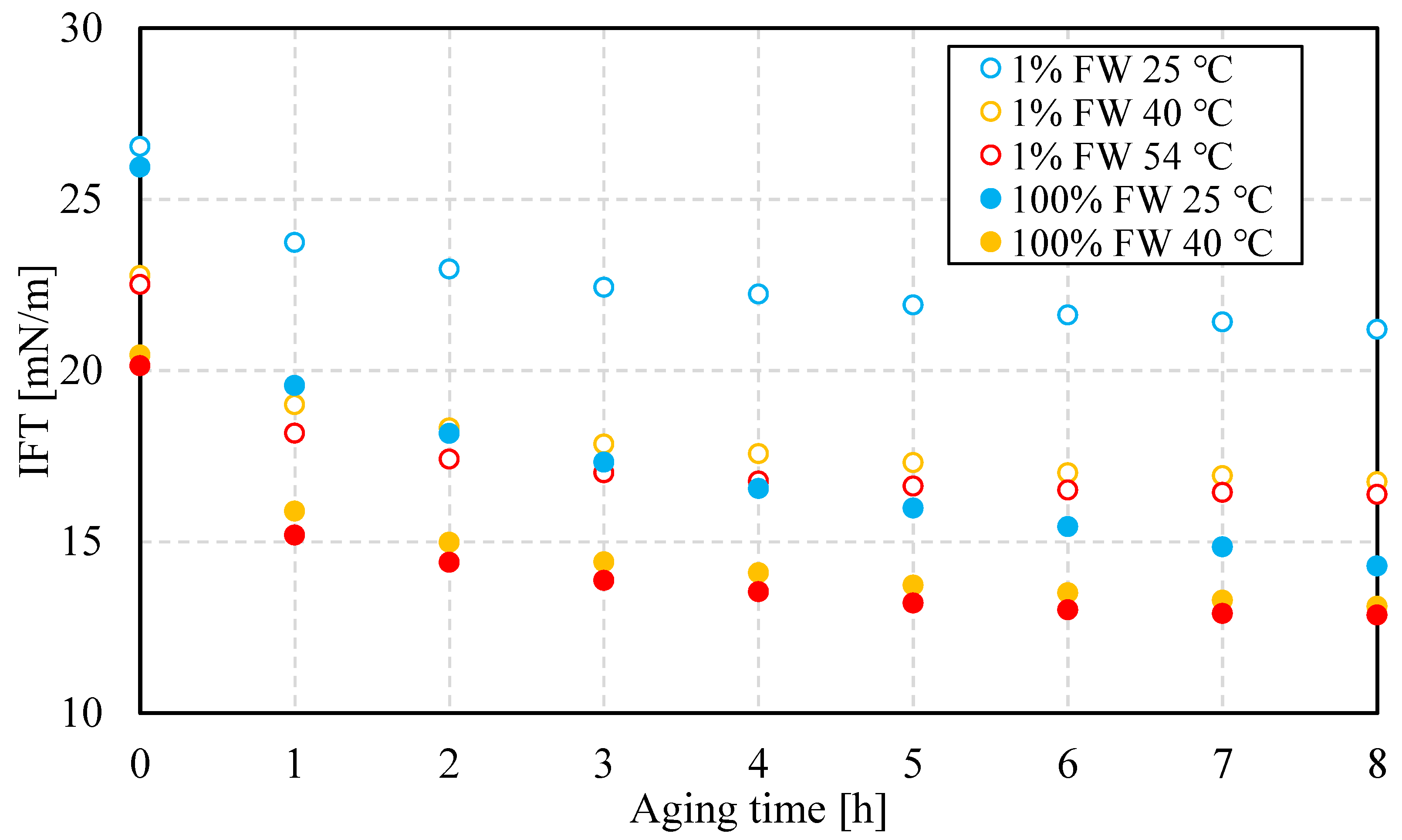

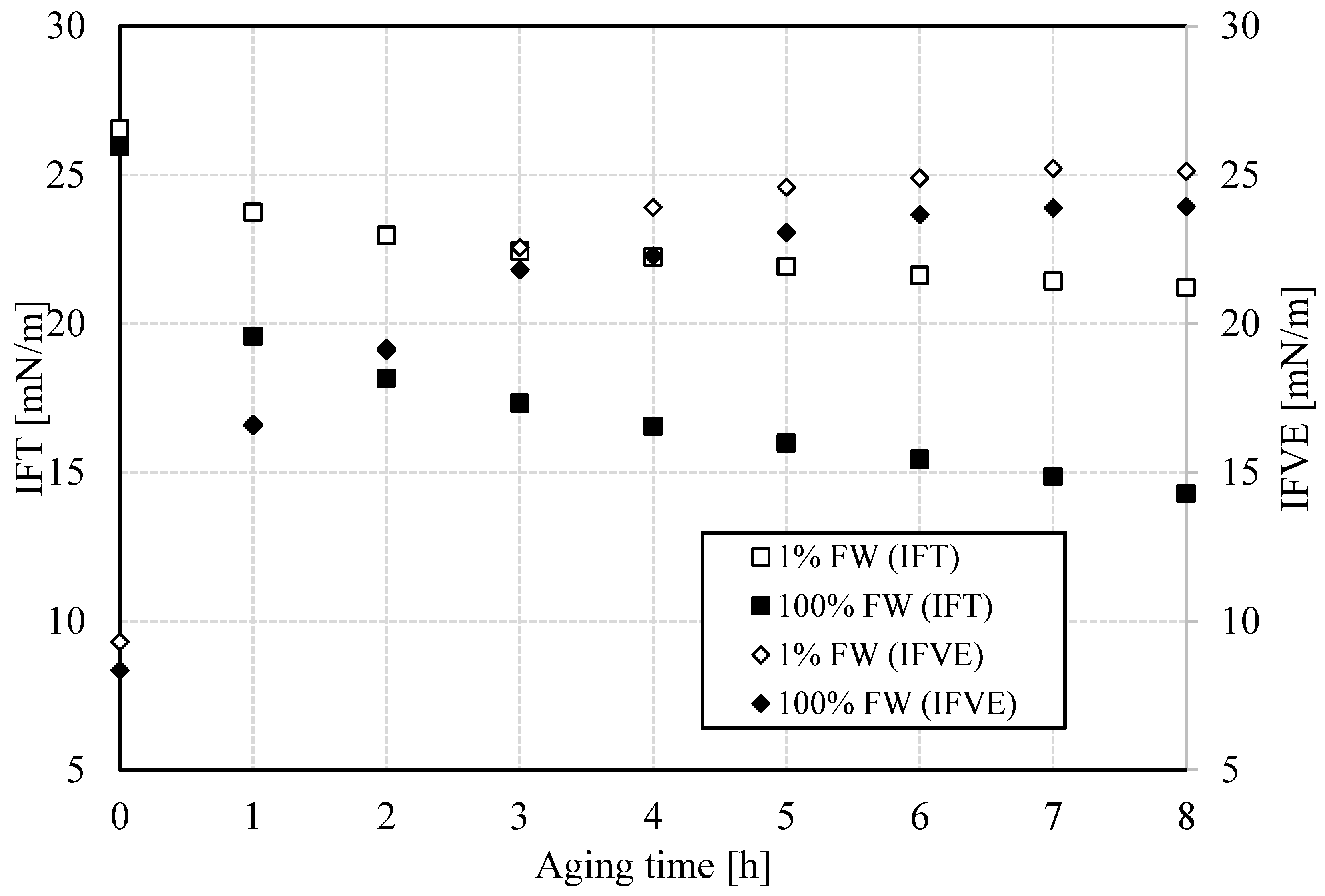

The coalescence of two drops involves the rupture of the water-oil interfacial film that mediates between them, and therefore, the study of the interfacial properties of the film is important to explain what happens in this stage of emulsion destabilization. The IFT experiences an exponential decay regardless of the brine used (

Figure 4). With the system containing formation water, there is a more pronounced decrease in IFT that led to a considerably lower IFT. This difference is due to the more significant migration of natural surfactants towards the interface. As proposed previously, a higher ionic strength in the brine could imply a shorter Debye length and a higher electrostatic gradient and therefore, a greater capacity to induce the migration of polar components of crude oil [

22]. However, in the same research, it was implied that compression of the double layer at higher salinity can diminish the attraction of polar molecules to the interface. As certain surface-active substances migrate from the bulk to the interface, not only a decrease in interfacial tensions is seen, but also an increase in interfacial viscoelasticity. After the initial diffusion of the surfactants, a reorganization and cross-linking stage occurs at the interface, which generates an interfacial film whose rigidity increases over time [

23]. Its conformation depends on the salinity as well. Specifically, at low salinity, the interfacial film becomes slightly stiffer.

3.1.5. Estimation of Sedimentation, Flocculation and Coalescence Rates

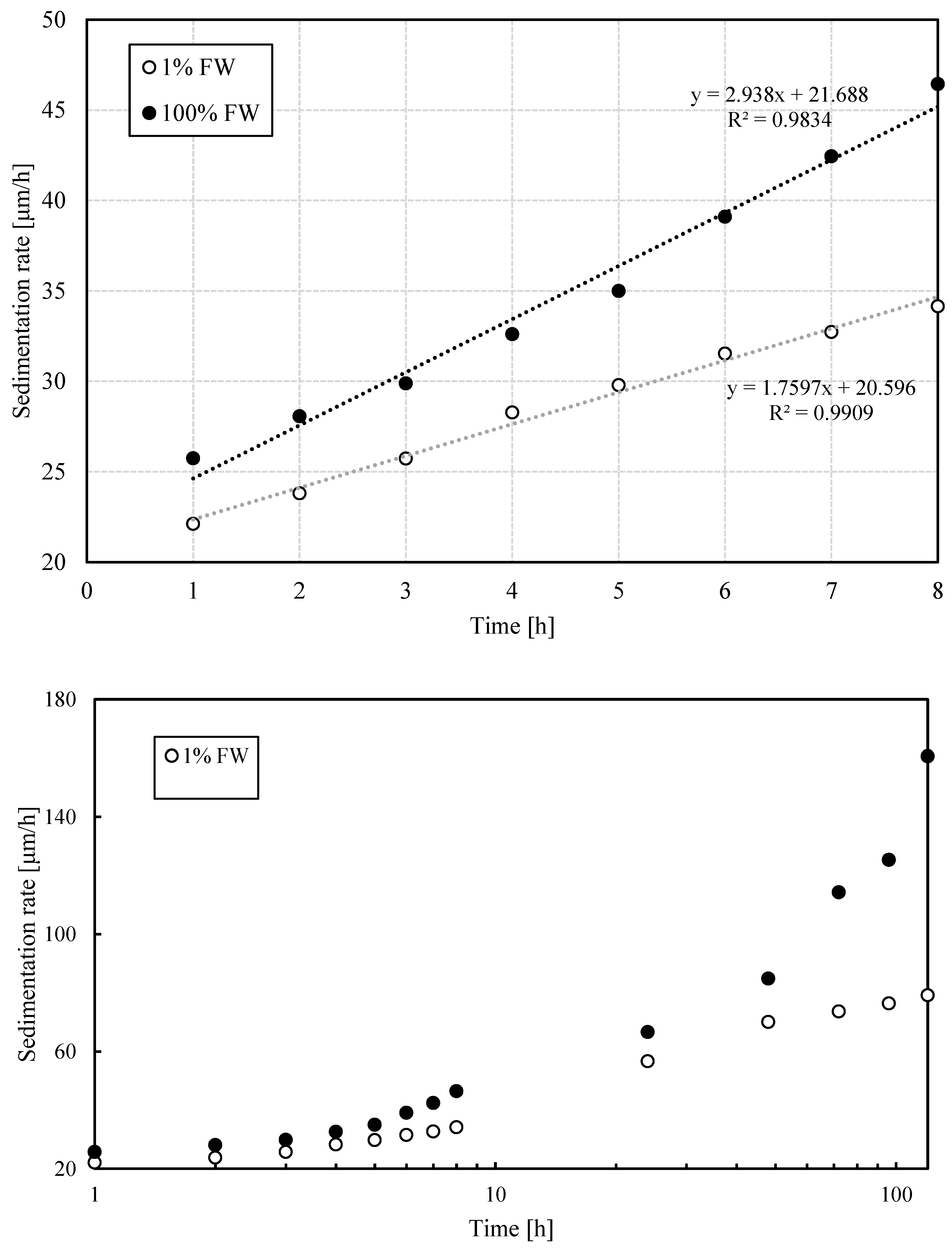

To quantify the rate of coalescence and flocculation, the growth rate of drop size and dispersion were analyzed. As shown in

Figure 5, aggregation is delayed in emulsions containing a low-salinity brine relative to their high-salinity counterpart. While the differences for both: the average (volumetric) and the standard deviation of the drop size are not as noticeable during the first 10 hours (top portion of

Figure 5), they are quite significant after 100 hours (bottom plot in

Figure 5). This observation provides strong evidence of differences in relative stability between emulsions formulated at the two different salinities in this work. This becomes clearer when the bottle test results are examined considering the DSD results.

The rate of dispersed phase sedimentation was estimated by means of Stokes' law. Sacha is a medium crude oil, so the water droplets were denser and consequently moved down to the bottom of the bottle. The initial size of the drops depends, among other parameters, on the agitation intensity. At 6 500 rpm, the initial average diameter of the drops was around 2.6 µm, which implied an initial sedimentation rate of 21 µm/h, independently of the salinity of the brine

. As time progressed, the simultaneous occurrence of flocculation and coalescence impacted the DSD, which in turn resulted in a progressive increase of sedimentation rates that now exhibited a salinity dependency. Specifically, emulsions prepared with diluted formation water exhibited considerably lower sedimentation rate changes, 1.8 µm/h

2, than emulsions prepared with formation water, 2.9 µm/h

2.

Figure 6 summarizes the calculation of sedimentation rates at the two aqueous phase salinity values. Notice the acceleration of the sedimentation rate as the emulsions estimated drop size increases. These results connect water resolution at both salinities with the inferred coalescence process derived from drop-size distribution measurements. The larger size droplets will more rapidly descend to the bottom of the bottles, where the pool of water will favor phase separation, given the more expedited coalescence between pooled water and droplets at the bottom of the bottle. One aspect of these processes that requires additional data is whether interfacial-film strengthening continues to build up over time. Given that after an extended period, phase separation seems to slow down for emulsions prepared with lower-salinity aqueous phase, this seems to be the case.

Regarding the repulsion forces between dispersed phase droplets, which contribute to the stability of the emulsions, the electrostatic and steric forces are remarkable. When crude oil and brine come into contact, ions from the brine migrate to the interface and contribute to the formation of an electrical double layer (EDL). The thickness of this layer depends on the ionic strength and the characteristics of the ions. In a low-salinity regime, a thick EDL, but with a weaker electrostatic gradient, is expected. This would lead to lower repulsions, and therefore lower stability in this type of emulsions. The experimental results show the opposite, which could reflect a greater relevance of the steric forces on this phenomenon, at least during the time scales investigated. On the other hand, significant compression of the EDL at high salinity likely weakens the net electric potential more significantly than low-salinity conditions, leading to a weaker attraction of polar molecules, such as asphaltenes, towards the interfaces. These arguments can, in a speculative fashion, indicate that buildup of the interface might be favored by conditions leading to dielectrophoretic attraction of polar molecules such as asphaltenes and resins. In practice, more than one mechanism might act on the interface as to explain the observations in this research. The following section will analyze the effect of temperature on the steric component of emulsion stabilization addressed by the study of the interfacial film formed between crude oil and brine.

3.2. Temperature Effect

Some authors have stated that the rate-limiting steps of the demulsification kinetics are flocculation and coalescence, and the consequent drainage of the droplets [

24]. For this reason, the analysis of this section mainly focuses on the interfacial film that hinders phase separation. It is important to keep in mind that all the mechanisms leading to an emulsion breakdown act on different time scales, which are influenced by temperature in different ways.

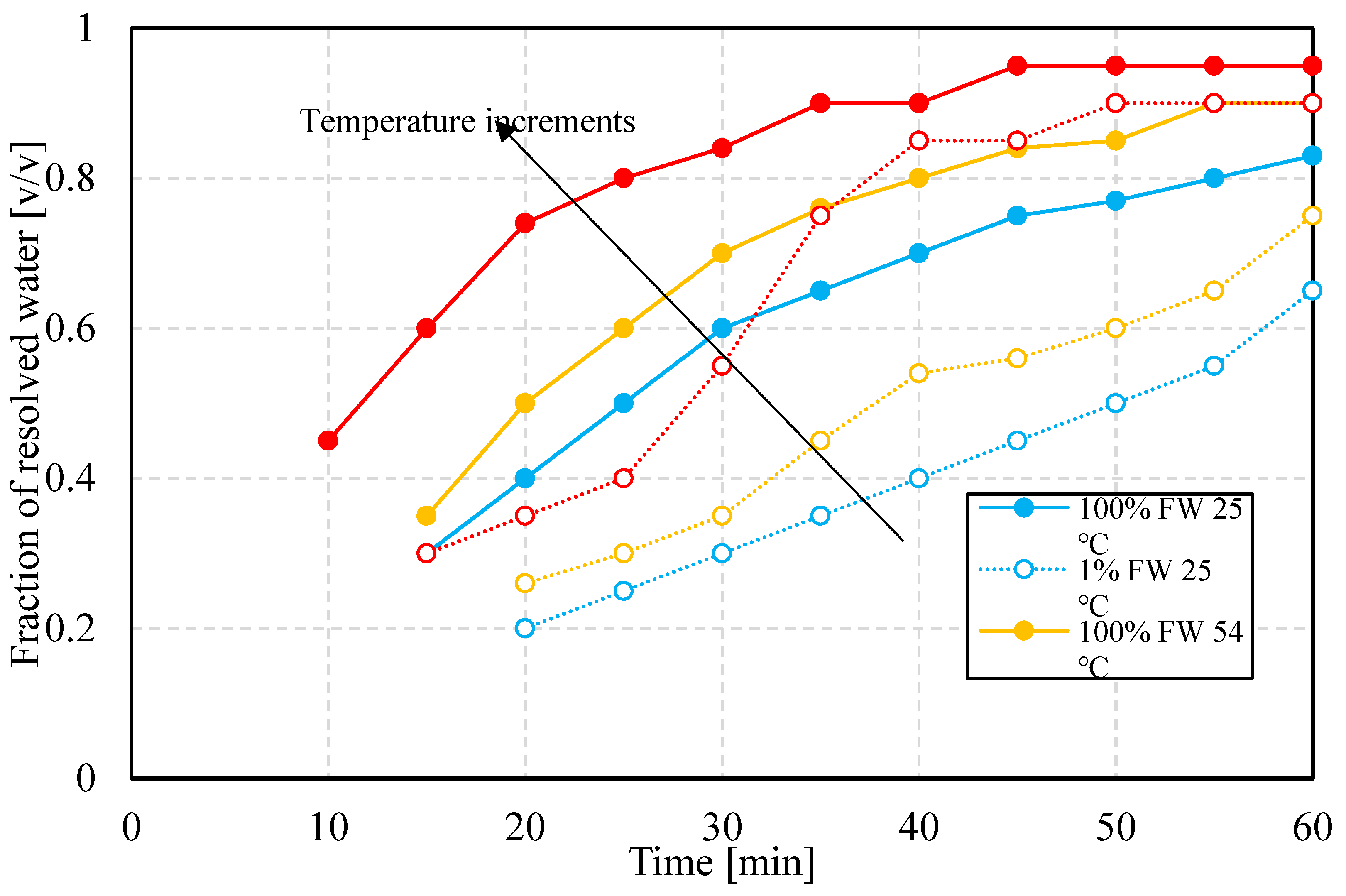

3.2.1. Bottle Tests

Figure 7 shows that fraction of resolved water as a function of time during the first 60 min. The first self-evident observation is that for both values of salinity, the resolved water fraction is higher, the higher the temperature. This part of the trend could be related to sedimentation rates, which is favored by the dependence of oil viscosity on temperature, i.e. lower viscosity as temperature is increased. Moreover, the faster sedimentation rate can trigger accelerated water resolution, before the interface stiffens as to hinder coalescence. Second, the final water volume fraction resolved depends on temperature rather than converging to the same value at the end of the observation time. This might have occurred because of the limited observation time. However, the volumetric fraction of resolved water is always lower at lower temperatures. The third observation is that emulsions prepared at the lower aqueous phase salinity are always more stable, in relative terms, than their counterparts at high salinity. This indicates that regardless of what the stabilization mechanism is, it seems to always favor lower-salinity conditions, regardless of temperature. It goes without saying that the differences between lower and higher salinity cases are smaller at higher temperatures. The last observation points to mechanisms beyond viscosity reduction as a function of increasing temperature. This hints that temperature-dependent interfacial mechanisms are at play. The rates of buildup might be discerned from trends of properties as functions of time.

3.2.2. Interfacial Properties

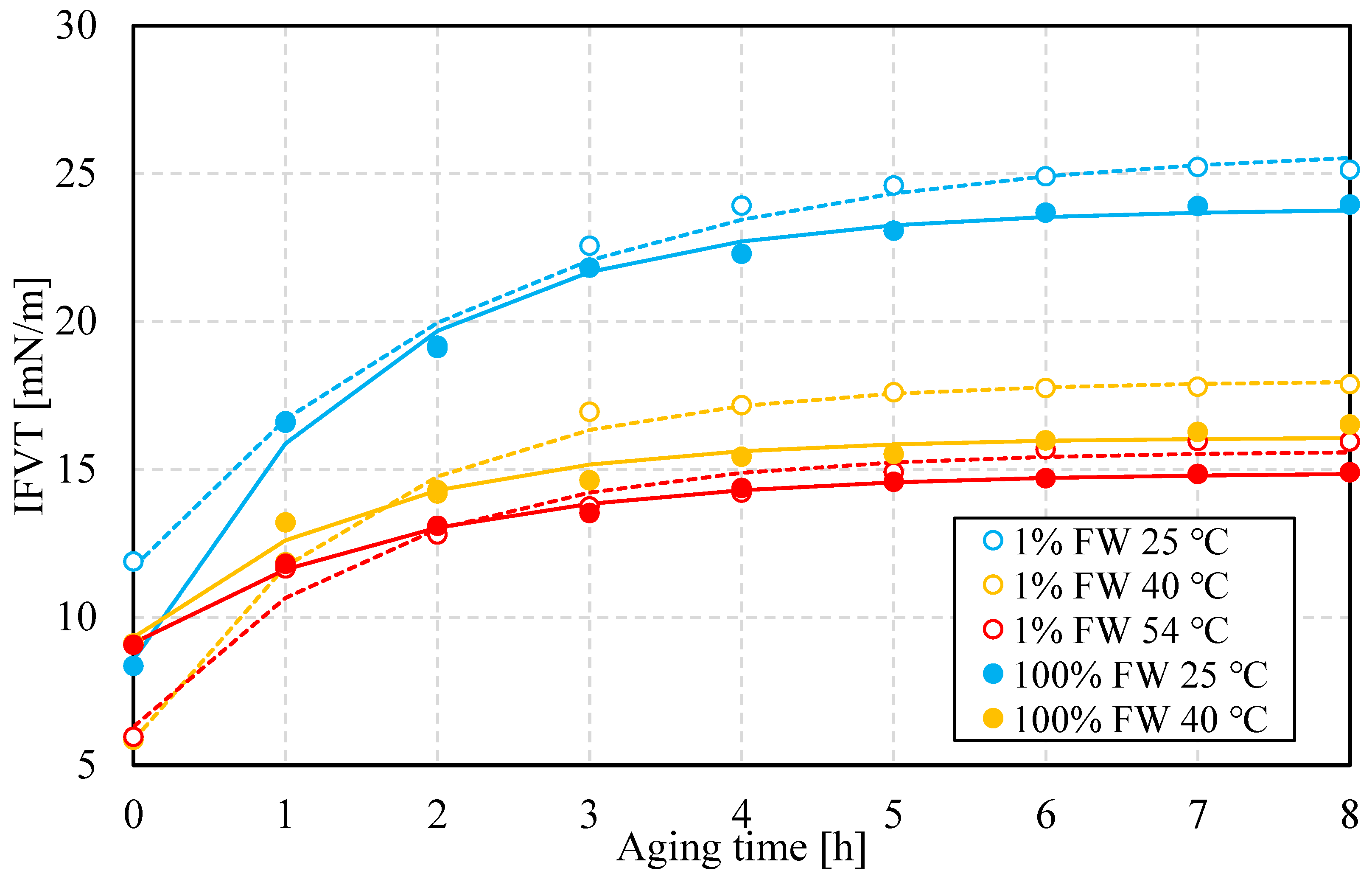

Bottle-test results herein indicate that temperature-dependent interfacial properties likely play a role in the relative stability of the specific macroemulsions in this work. The two main properties studied here are the IFT and IFVE modulus. The former, measured via the pendant-drop technique, impacts chemical potential gradient, a measure of the driving force for coalescence, between drops or a drop in contact with the bottom water reservoir in bottle tests. In isolation, the higher the chemical potential gradient, the easier coalescence occurs. For two drops of different radii, in the absence of kinetic barriers, the smaller drop releases de excess pressure to equilibrate it with the larger drop, i.e. until the interfacial research a new equilibrium situation.

Figure 8 (top) shows results of the IFT at three values of temperature for both aqueous-phase salinities. The first observation is that the IFT, regardless of temperature and salinity, decreases and approaches a plateau value that depends on the specific conditions of the experiments. This is a well-known trend that reflects interfacial buildup and conformation [

25]. This implies a kinetic process of interface formation, which likely includes multicomponent molecular moieties.

The bottom portion of

Figure 8 shows the IFVE modulus, measured at 0.1 Hz using dilatational rheology on the same pendant-drop system used for the IFT measurements, as a function of time. As the figure shows, the IFVE modulus decreases with increasing temperature. Its value is slightly larger at low salinity compared to its high-salinity counterpart. This contrast could contribute to differences in relative stability at the same temperature, but this must also consider the value of IFT. Previous work on interfacial failure in the presence of an elastic interface shows that the ratio of elastic modulus to IFT serves as a kinetic barrier to snap-off [

26,

27]. A similar mechanism might act during the coalescence process, though the failure mechanism is different, likely through failure of interfacial dimples, rather than snap-off or pinch off.

An exponential saturation fitting procedure was followed to estimate the rate or kinetics of interfacial film formation, essentially assuming a first-order kinetic process overall:

where

is the viscoelastic modulus,

is the initial viscoelastic modulus,

is the incremental value,

is the buildup time, and

is the aging time. Moradi and Alvarado [

25] followed a similar approach to estimate the kinetics of interface buildup but wrote the equation somewhat differently.

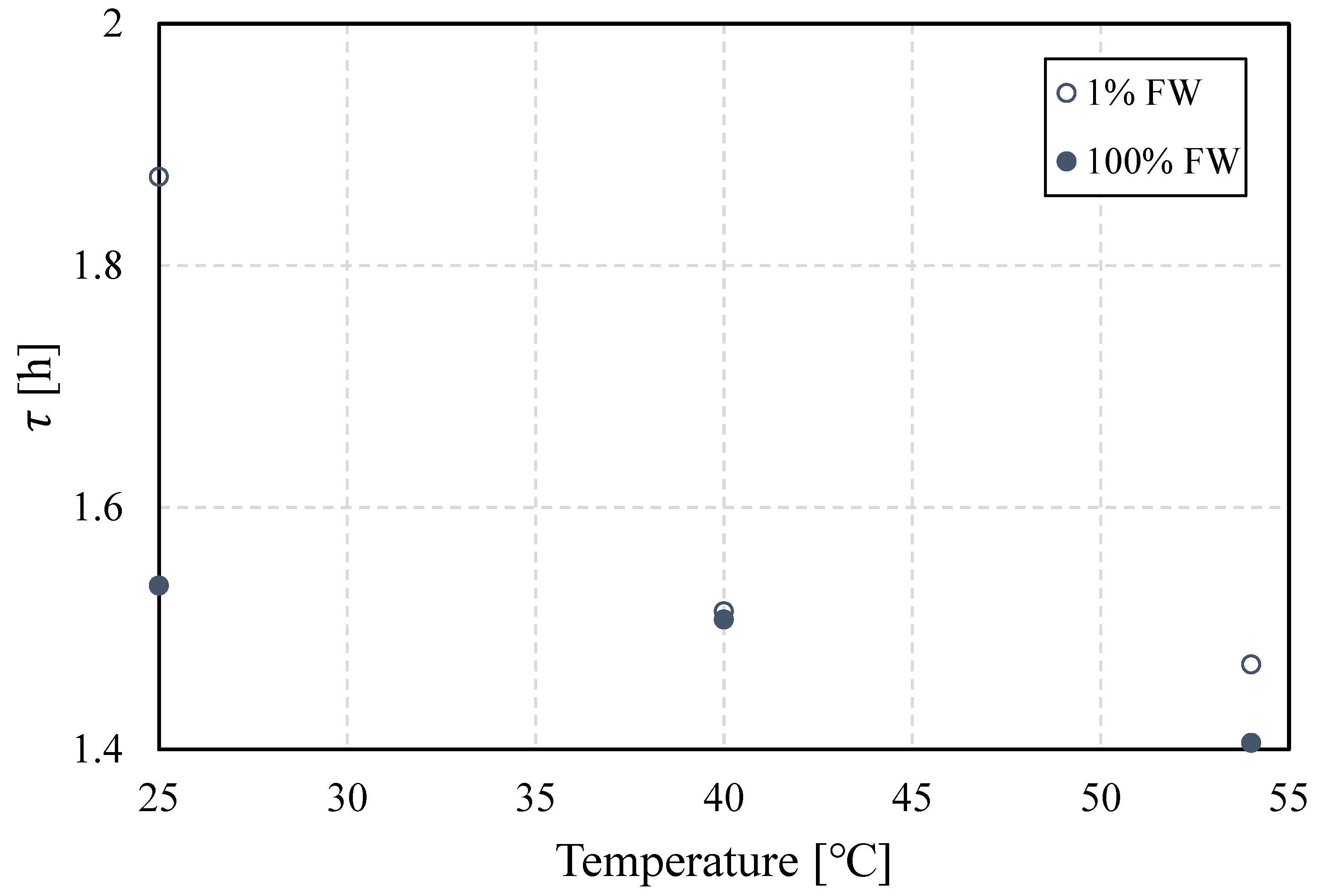

Figure 9 depicts the buildup or relaxation rate time as a function of temperature for both values of salinity. At the three temperatures set for these measurements, the value of this time scale is higher at low salinity, except at 40

oC, which indicates a greater buildup rate. It is important to highlight that as described in previous work (and references therein) [

25], the buildup of the interface likely follows an initial step dominated by molecular diffusion towards the interface, and then a second one controlled by local structuring or organization of the interface, e.g. stacking or linkage. Relaxation time lumps both mechanisms, regardless of which one dominates. The driving force that attracts polar material towards the water-oil interface might control the thickening of said interface, but structuring might be in part responsible for its stiffening.

As time elapses, flocculation, coalescence and sedimentation act simultaneously, but these mechanisms act on different time scales. High salinity implies higher density contrast between the oil and water phases, which benefits sedimentation. This, in turn, favors phase separation through water resolution at the bottom of the bottle. This effect is favored at higher temperatures, from a combination of changes in oil properties, perhaps more importantly due to oil-viscosity reduction. On the other hand, the rates of coalescence are higher at higher salinity, which indicates that lower salinity contributes to a more resilient interface. While IFT is higher at lower salinity, the dilatational interfacial modulus has a higher value. This is an indicator of a stiffer interface that likely suppresses coalescence.

4. Conclusions

Water-in-oil emulsion stability analysis and interfacial measurements in this work lead to the following conclusions:

A comprehensive stability analysis of W/O emulsions prepared with the Sacha crude oil was conducted to elucidate emulsion breakdown controls under conditions established in this research. The resulting emulsions are more resilient at lower salinity. This is the first time that emulsions with oil originated from this basin have been analyzed in this context in the open literature, to the best of our knowledge.

Emulsions, regardless of aqueous-phase salinity, are more stable at lower temperatures. This is explained by the formation of less viscoelastic water-oil interfaces, as viscoelastic modulus results show. This in turn indicates that lower salinity favors interfacial viscoelasticity.

The effectiveness of the phase-separation process at higher-salinity of the aqueous phase could be explained based on an increased density contrast between water and oil, which favors the sedimentation rate, accompanied by a relative increase in the coalescence rate, as results here showed.

Author Contributions

Jordy Sarmas-Farfan: Methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, visualization. Antonio Diaz-Barrios: Methodology, validation, investigation, writing—original draft preparation. Teresa E. Lehmann: resources, writing—review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition. Vladimir Alvarado: Conceptualization, Methodology, validation, resources, data curation, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported as part of the Center for Mechanistic Control of Unconventional Formations (CMC-UF), an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science under DOE(BES) Award DESC0019165.

Acknowledgments

To PETROAMAZONAS EP in the persons of Rommel Castillo (Manager of Sacha Oilfield), Dixon Taboada and Rodrigo Loyola (Superintendents of Sacha Oilfield), for allowing the collection of crude oil samples in the facilities of Sacha Oilfield. To Patricio Llerena (Technical Manager of Overtech) and Bryan Bravo (Operations Coordinator of Overtech), for sample preservation and transportation. To professors Luis Calle and José Condor (Universidad Central Ecuador), Francisco Quiroz and José Ivan Chango (CIAP at Escuela Politécnica Nacional, Ecuador) and Yachay Tech University, Ecuador for allowing the access and providing assistance in the laboratories.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| W/O |

water-in-oil (W/O) |

| O/W |

Oil-in-Water |

| DSD |

droplet-size distribution |

| TD-NMR |

Time-Domain Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| ODG |

Oscillating drop generator |

| FW |

Formation water |

| TDS |

Total Dissolved Solids |

| IFT |

Interfacial tension |

| IFVE |

interfacial viscoelasticity |

| PFG-NMR |

Pulsed Field Gradient Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| EDL |

Electrical double layer |

References

- Kim, Y.H.; Wasan, D.T.; Breen, P.J. A study of dynamic interfacial mechanisms for demulsification of water-in-oil emulsions. Colloids Surf. A 1995, 95, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, S.; He, Y.; Zhong, L.; Hao, T.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Gao, P.; Guo, Q. Experimental study of produced fluid emulsification during water/steam flooding for heavy oil recovery. ENERG FUEL 2022, 36, 14838–14851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaref, S.; Ayatollahi, S. The effect of brine salinity on water-in-oil emulsion stability through droplet size distribution analysis: A case study. J. Disper. Sci. Technol. 2018, 39, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhong, L.; Lyu, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S. W/O emulsions generated by heavy oil in porous medium and its effects in reemulsification. Fuel 2022, 310, 12344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, V.; Wang, X.; Moradi, M. Stability Proxies for water in oil emulsions.and implications in aqueous-based enhanced oil recovery. Energies 2011, 4, 1058–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, N.; Alzahid, Y.; AlSofi, A.; Ali, M.; Hoteit, H. Review on microemulsions for conformance improvement technology: fundamentals, design considerations and perspectives. ENERG FUEL 2023, 37, 858–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.; Baydak, E.; Yarranton, H.; Sztukowski, D.; Ali-Marcano, V.; Gong, L.; Shi, C.; Zeng, H. Role of aqueous phase chemistry, interfacial film properties, and surface coverage in stabilizing water-in-bitumen emulsions. ENERG FUEL 2016, 30, 5240–5252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, T.D.; Leal-Calderon, F.J. Forces between emulsion droplets stabilized with Tween 20 and proteins. Langmuir 1999, 15, 8813–8821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhou, J.; He, C.; He, L.; Li, X.; Sui, H. The formation, stabilization, and separation of oil-water emulsions: a review. Processes 2022, 10, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajun, Z.; Zhexi, T.; Zhongqi, Y.; Hongzhi, S.; Yanping, W.; Yufei, Z. Research status and analysis of stabilization mechanisms and demulsification methods of heavy oil emulsions. Energy Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 4158–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ting, Y.; Hu, J.; Hsieh, S. Techniques and methods to study functional characteristics of emulsions systems. JFDA 2017, 25, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, E. Strategies to control and inhibit the flocculation of protein-stabilized oil-in-water emulsions. FOOD HYDROCOLLOID. 2019, 96, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, H.; Carreras, E.; Schmitt, V.; Lequeux, F. Coalescence in concentrated emulsions: theoretical predictions and comparision with experimental bottle test behavior. Soft Matter, 2020, 16, 10301–10309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulredha, M.; Hussain, S.; Abdullah, L. Overview on petroleum emulsions, formation, influence and demulsification treatment techniques. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 3403–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russ, J.C. Image analysis of food microstructure. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004.

- Alade, O.; Mahmoud, M.; Al Shehri, D.; Sultan, A. Rapid determination of emulsion stability using turbidity measurement incorporating artificial neural network (ANN): experimental validation using video/optical microscopy and kinetic modeling. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 5910–5920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manickam, S.; Sivakumar, K.; Pang, C. Investigations on the generation of oil-in-water (O/W) nanoemulsions trough the combination of ultrasound and microchannel. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 69, 105258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, D.; White, R. The digitalization of bottle tests nuclear magnetic resonance evaluation of emulsion stability. J. Pet. Technol. 2020, 7, 40–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoori, G.; Vazquez, D.; Shariaty-Niassar, M. Polidispersity of heavy organics in crude oils and their role in oil well fouling. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2007, 58, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhou, J.; He, C.; He, L.; Li, X.; Sui, H. The formation, stabilization, and separation of oil-water emulsions: a review. Processes 2022, 10, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadem, B.; Parrott, A.; Nordon, A.; Sheibat-Othman, N. Low field high resolution PFG-NMR to predict the size distribution of inner droplets in double emulsions. Eur. J. Lipid. Sci. Technol 2021, 123, 2000193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, B.; Saraji, S. Transient interfacial rheology and polar component dynamics at oil-brine interfaces. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 624, 126773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmas-Farfan, J.; Medina-Rodriguez, B.; Alvarado, V. Dynamic stability of a crude oil/brine interface: effect of anion type. Fuel 2023, 335, 127002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Shi, P.; Duan, M.; Fang, S.; Ma, Y. Investigation of demulsification efficiency in water-in-crude oil emulsions using dissipative particle dynamics. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 62971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.; Alvarado, V. Influence of Aqueous-Phase Ionic Strength and Composition on the Dynamics of Water–Crude Oil Interfacial Film Formation. ENERG FUEL 2016, 30, 9170–9180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, P.; Carvalho, M.S. , Alvarado, V. Snap-off in Constricted Capillary with Elastic Interface. Phys. Fluids. 2016, 28, 012104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, P.; Alvarado, V. Stability of liquid bridge with elastic interface. RSC Adv 2017, 7, 49344–49352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).