1. Introduction

Digital business simulations are increasingly used in higher education as a bridge between theoretical knowledge and practical skill development. Traditional classroom settings often focus on lectures and exams that emphasize conceptual understanding; however, students frequently struggle to apply these concepts in real-world environments. To address this gap, many institutions have introduced digital simulation-based exercises that immerse learners in complex, risk-free scenarios requiring them to collaborate, make strategic decisions, and adapt to changing conditions.

This experiential learning approach is particularly relevant in business programs, as it mirrors the challenges students will encounter in the workplace. By managing a virtual company, for example, students can practice analyzing financial reports, coordinating team efforts, and exercising leadership under time pressure, all of which build competencies prized by future employers. Previous studies highlight that simulations can positively influence work-integrated learning, foster accountability, and bolster students’ confidence in their decision-making abilities [

1,

2,

3]. Such evidence underpins the increasing adoption of business simulations across higher education curricula worldwide.

Despite the noted benefits of simulation-based learning, questions remain about how effectively these simulations develop specific soft skills, such as decision-making, teamwork, and leadership, and whether these skills translate into overall job market preparedness. Many higher education institutions invest considerable resources in digital simulations without a clear understanding of their measurable impact on employability. Additionally, while students may report anecdotally that these simulations are “helpful,” rigorous evidence of improved career readiness is often lacking or not clearly tied to the development of distinct competencies. This study addresses these gaps by systematically examining whether (and how) a semester-long business simulation enhances key professional skills relevant to students’ future careers.

In an increasingly competitive job market, graduates are expected to demonstrate strong collaborative and leadership capabilities alongside analytical and decision-making proficiency. Surveys of employers consistently report that over 80% prioritize teamwork and leadership potential when hiring entry-level candidates [

4,

5]. If business simulations can significantly improve these competencies, then institutions have a powerful digital and pedagogical tool at their disposal. The present research is therefore significant not only for educators seeking evidence-based teaching strategies but also for students whose employability may hinge on attaining skills that simulations can cultivate. By providing empirical insights into the effectiveness of a specific digital simulation exercise, this study can inform curriculum design, resource allocation, and best practices in experiential learning through digital simulation platforms.

The present study evaluates the effectiveness of a digital business simulation in developing students’ decision-making skills, teamwork skills, leadership skills, and overall job market preparedness. After completing the simulation, students responded to surveys measuring their perceived skill development in these areas. We tested the following hypotheses (H1–H5):

H1 (Decision-Making Improvement): Mean decision-making skill development scores will be significantly higher than the neutral midpoint (3 on a 1–5 Likert scale), indicating perceived improvement.

H2 (Teamwork Improvement): Mean teamwork skill development scores will be significantly higher than the neutral midpoint.

H3 (Leadership Improvement): Mean leadership skill development scores will be significantly higher than the neutral midpoint.

H4 (Career Preparedness): Mean job market preparedness scores will be significantly higher than the neutral midpoint.

H5 (Predictive Model): Improvements in decision-making, teamwork, and leadership skills will positively predict students’ job market preparedness.

By examining these hypotheses, we aim to understand not only if the simulation was effective in each area, but also how these skill domains interrelate and contribute to overall career readiness. We used Marketplace Simulations in a Higher Education Institution in Lisbon (Lisbon Accounting and Business School, Polytechnic University of Lisbon – ISCAL). These digital simulations are a powerful yet entertaining way to learn how to compete in a fast-paced market where customers are demanding and the competition is working hard to take away the business [

6,

7]. It is not only a motivational learning experience but also a transformational one. Working in teams, a group of students build an entrepreneurial firm, experiment with strategies, compete with other participants in a virtual business world filled with tactical detail, and struggle with business fundamentals and the interplay among marketing, manufacturing, logistics, human resources, finance, accounting, and team management. Students take control of an enterprise and manage its operations through several decision cycles. Repeatedly, they must analyze a situation, plan a strategy to improve it, and then execute that strategy out into the future. The group faces great uncertainty both from the outside environment and from their own decisions. Incrementally, students learn to skillfully adjust their strategy as they discover the nature of real-life decisions, conflicts, trade-offs, and potential outcomes.

While digital simulations are increasingly adopted in education, few studies examine how their technical design (e.g., iterative feedback loops, virtual team dynamics) directly influences skill acquisition. This study addresses that gap by analyzing a Marketplace Simulation platform, a digital tool replicating real-world business environments, to assess its efficacy in fostering career-ready competencies.

2. Theoretical Framework

Business simulations draw heavily on experiential learning theory and constructivist principles as a foundation for their effectiveness in education. Experiential learning theory, as articulated by Kolb, posits that learning is a cyclical process involving concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation [

8,

9]. In a simulation, students engage in a “concrete experience” by managing realistic business scenarios, then reflect on outcomes, derive conceptual insights, and apply those insights in subsequent rounds of decision-making. This cycle mirrors Kolb’s model and explains why simulations are powerful learning tools; students learn by doing, feeling the consequences of their decisions and adjusting their strategies accordingly. Prior research characterizes business simulation games (BSGs) as “experiential learning tools” that let students run a virtual company in a risk-free environment, make strategic choices, experience the results, and grow from their failures [

10]. This hands-on process aligns with Kolb’s view that active experience and reflection deepen learning, making simulations a natural fit for business education courses that aim to bridge theory and practice [

9].

Constructivist learning theory further justifies the use of digital simulations in business education. Constructivism holds that learners actively construct knowledge by integrating new experiences with their existing knowledge base [

11]. Rather than passively receiving information, students in a simulation must interpret events, solve problems, and adapt their understanding through continuous feedback. Learning is highly context-driven in this view: knowledge is best acquired in realistic, relevant settings where learners can apply concepts [

12,

13]. Business simulations provide exactly this kind of context, situating students in lifelike business environments that demand decision-making, teamwork, and problem-solving. In constructivist terms, the simulation’s authenticity allows learners to build new knowledge upon the foundation of previous learning. They test hypotheses (business strategies), see the outcomes, and restructure their understanding of business concepts through experience. The social aspect of constructivism is also at play; many simulations involve team-based play, echoing Vygotskian ideas that social interaction and collaboration are crucial to learning [

14].

As students negotiate decisions and roles within a team, they are collaboratively constructing knowledge. Both experiential learning theory and constructivism suggest that an active, learner-centered pedagogy like a digital simulation is pedagogically sound: it engages students in authentic experiences, encourages reflection and conceptualization, and enables learners to take ownership of their learning process. These theories provide a strong theoretical framework explaining why simulations can effectively develop skills in business education [

15].

A growing body of empirical research indicates that business simulations can significantly enhance students’ soft skills and preparedness for the workplace. A recent systematic review of 57 studies (2015–2022) concluded that business simulations tend to improve a range of learning outcomes, including knowledge acquisition, cognitive skills, and interactive skills [

16]. In particular, simulations have been found to strengthen students’ decision-making capabilities. For example, a systematic review focusing on decision-making reported that the majority of simulation-based learning experiences led to improved decision-making outcomes for students [

10]. Through repeated cycles of analysis and choice in a game environment, students practice making business decisions under pressure, which can enhance their analytical thinking and judgment. Studies also link simulations to higher-order cognitive benefits; participating in complex business games appears to foster strategic thinking and problem-solving skills.

These cognitive gains are noteworthy because they correlate with workplace success; the ability to analyze situations and make sound decisions is a trait valued by employers. Business simulations have similarly been shown to cultivate teamwork and leadership skills among students. Many simulation exercises are team-based, requiring participants to collaborate on running a virtual company or project. Research findings indicate that such experiences promote effective teamwork behaviors. In fact, simulations have been demonstrated to successfully improve team dynamics, collaboration, and even social-emotional skills in educational settings [

17]. For instance, working through a simulation scenario pushes students to communicate, resolve conflicts, and coordinate responsibilities within their team, mirroring real-world team projects. Siewiorek et al. [

18] observed that a management simulation game allowed different leadership styles to emerge among business students and provided a safe space to practice leadership roles and receive feedback. Overall, multiple studies echo that immersive simulations build interpersonal skills [

6,

16,

19,

20,

21]. These findings are significant given that employers highly prioritize such soft skills. Surveys by the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE) show that over 80% of employers seek candidates with strong teamwork abilities, and a large majority value leadership and problem-solving skills as well [

22]. By providing structured opportunities to practice teamwork and leadership, simulations help students develop the very competencies that the job market demands.

Beyond decision-making and teamwork, digital simulations can boost students’ confidence and readiness for real business challenges, thereby enhancing their job market preparedness. Several studies have linked simulation participation to greater self-efficacy in business tasks and a perception of improved employability. For example, Lim et al. [

23] found that students who engaged in a stock trading simulation felt it was effective in fostering their personal development, future readiness, and self-directed learning, all of which contributed to higher employability skills. In their study, the simulation experience significantly improved learners’ self-reported preparedness for the workforce, confirming that “educational simulations are effective tools for developing soft skills and 21st-century competencies” needed in a modern workplace.

Similarly, Hernandez-Lara et al. [

24] observed that business games can increase students’ awareness of real-world business dynamics and enhance skills like opportunity recognition and adaptability (qualities that improve career readiness).

Students often report that after a simulation-based course, they feel more confident in handling job-related problems and working in team settings, indicating a higher state of career preparedness. From an academic performance standpoint, simulations have also been associated with better integration of knowledge and skills. Chulkov and Wang [

17] noted that a finance simulation led to higher exam scores on applied topics and improved students’ professional skill development and course satisfaction.

The literature to date paints an encouraging picture: business simulations enhance soft skills (decision-making, teamwork, leadership) and provide experiential learning that translates into greater employability. By bridging classroom theory with practical application, digital simulations not only impart business acumen but also help students cultivate the personal and interpersonal skills required to transition successfully into the job market.

In practical terms, a student who is “job-market prepared” should be able to present themselves well to employers (e.g. via resumes and interviews), and once hired, perform effectively and continue learning on the job. In the context of simulation-based learning, job market preparedness is an ultimate goal; simulations are used as a pedagogical method to increase students’ readiness for real-world employment. By engaging in realistic business simulations, students can make connections between academic theory and practical application, thereby improving their work-readiness. For instance, managing a simulated company’s finances may deepen a student’s understanding of financial concepts and simultaneously improve their confidence to handle similar tasks in an actual job.

Likewise, the soft skills developed (decision-making, teamwork, leadership, problem-solving, communication) all contribute to a student’s employability. Many educators incorporate business simulations with the explicit aim of producing graduates who can “hit the ground running” in their careers, that is, graduates who have practiced tackling business problems, working in teams, and making decisions in an environment that mimics real job conditions. Job market preparedness is often assessed through outcomes like student self-perception of readiness, feedback from internship supervisors, or job placement rates. While business simulations are not a panacea, they are viewed as a high-impact practice that can significantly enhance these indicators of career readiness [

23].

By providing experiential learning that ties together decision skills, teamwork, and leadership in a practical context, simulations help students build a portfolio of competencies that make them more “employable” in the eyes of recruiters. This concept underscores the ultimate rationale for using business simulations: beyond academic learning, they aim to produce graduates who are well-equipped for the demands of the modern business workplace.

3. Methods

The study cohort comprised forty-two undergraduate business students (N = 42) enrolled in a capstone course (International Business Management), all of whom participated in a semester-long business simulation as a mandatory curricular component. Participants were predominantly final-year students preparing for workforce entry; however, demographic details were not collected as part of the survey protocol.

The virtual simulation required students to collaborate in teams tasked with managing a virtual company, wherein they iteratively formulated and executed strategic decisions across functional domains, including marketing, finance, and operations, over multiple rounds. Upon simulation completion, participants were invited to complete four self-administered questionnaires designed to assess perceived skill development in discrete learning constructs: decision-making, teamwork, leadership, and job market preparedness. Survey participation was voluntary, and responses were anonymized using unique student identification codes to ensure confidentiality.

Each survey instrument consisted of 16 Likert-scale items (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree) accompanied by an open-ended qualitative prompt. The Likert items were framed as positively worded assertions regarding skill enhancement attributable to the simulation. For decision-making skills, participants rated statements such as, “Participating in the business simulation improved my ability to analyze complex business problems effectively,” with items probing analytical thinking, data-driven decision-making, risk assessment, and adaptive decision strategies. The teamwork skills survey included items like, “The simulation helped me understand the importance of actively listening to others’ perspectives in a team setting,” addressing communication efficacy, collaborative goal attainment, conflict resolution, role flexibility, and collective accountability. Leadership skills were evaluated through statements such as, “The business simulation improved my ability to take initiative in leadership roles,” encompassing dimensions such as strategic visioning, team motivation, feedback delivery, delegation, ethical judgment, and stress management. Finally, the job market preparedness scale featured items like, “After completing the business simulation, I feel more prepared to handle real-world job challenges and responsibilities,” targeting career readiness facets such as applied business knowledge, decision-making confidence, cross-functional teamwork, problem-solving agility, and leadership self-efficacy in professional contexts.

This methodological design ensured a structured, multi-dimensional assessment of skill development outcomes aligned with experiential learning objectives and employer competency frameworks.

For each construct, a composite score was calculated by averaging the 16 item ratings, providing an overall score for that skill domain for each student. A higher score indicates a greater self-reported skill development or preparedness due to the simulation. The internal consistency (reliability) of each set of 16 items was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha (α). We considered α ≥ .70 as acceptable reliability for research purposes.

Using SPSS v.28, we conducted descriptive statistics for all Likert items, including mean, median, standard deviation (SD), and response distribution (percentage of respondents selecting each scale point). To test H1–H4, one-sample t-tests (two-tailed) compared the mean composite score of each construct against the neutral midpoint value of 3. For H5, we performed Pearson correlation analyses among the four composite variables (Decision-Making, Teamwork, Leadership, and Job Preparedness) and a multiple linear regression with Job Preparedness as the dependent variable and the other three composites as independent predictors. All statistical tests used a significance level of α = .05 (with p < .05 considered significant).

4. Results

All Likert scale items showed mean scores above the midpoint of 3, indicating generally positive perceptions of skill improvement.

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4 present the descriptive statistics for each survey item by construct. Students tended to agree that the simulation enhanced their skills, with most item means in the range of M = 3.5–4.5 out of 5.

Medians were typically 4 (“Agree”) for most items, reflecting a central tendency toward agreement. The distributions of responses further illustrate this trend. For example, 78.6% of students agreed or strongly agreed that the simulation improved their ability to analyze complex business problems, while only 7.1% disagreed (and 14.3% were neutral). Even on items with relatively lower ratings, a majority of students still reported positive outcomes. One such item was “The simulation helped me balance short-term gains with long-term business sustainability when making decisions.” On this question, 69% agreed/strongly agreed, 9.5% were neutral, and about 21% disagreed. This item had one of the lowest means in the decision-making survey (M = 3.69, SD = 1.24), suggesting that balancing short-term vs. long-term decisions was a bit more challenging or yielded mixed perceptions.

In contrast, other decision-making items had higher endorsement (e.g., “Considering multiple alternative solutions before making a final decision” had M = 4.12, SD = 0.96, with 81% agreement), indicating strong perceived improvement in analytical deliberation.

Note: (a) “Disagree” includes responses 1 and 2 on the Likert scale (Strongly Disagree or Disagree). (b) “Agree” includes responses 4 and 5 (Agree or Strongly Agree). Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Table 1.

Decision-Making Skill Development (Likert-scale 1=Strongly Disagree to 5=Strongly Agree, N = 42 per item).

Table 1.

Decision-Making Skill Development (Likert-scale 1=Strongly Disagree to 5=Strongly Agree, N = 42 per item).

| Construct & Item (Abbreviated) |

Mean |

Median |

SD |

% Disagree(a) |

% Neutral |

% Agree(b) |

| Decision-Making Skill Development |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Analyze complex business problems effectively |

3.88 |

4 |

1.02 |

7.1% |

14.3% |

78.6% |

| Break down business challenge into components |

3.90 |

4 |

1.19 |

19.0% |

9.5% |

71.4% |

| Confident assessing options before decision |

3.90 |

4 |

0.93 |

4.8% |

7.1% |

88.1% |

| Enhanced critical thinking with data |

3.69 |

4 |

1.24 |

23.8% |

14.3% |

61.9% |

| Data-driven vs intuition in decisions |

4.05 |

4 |

0.94 |

4.8% |

9.5% |

85.7% |

| Interpret financial reports for strategy |

4.26 |

4 |

0.87 |

2.4% |

4.8% |

92.9% |

| Consider multiple alternatives before final decision |

4.12 |

4 |

0.96 |

2.4% |

11.9% |

85.7% |

| Balance short-term vs long-term decisions |

3.69 |

4 |

1.35 |

21.4% |

9.5% |

69.0% |

| Aware of risks and consequences of decisions |

4.05 |

4 |

0.90 |

4.8% |

7.1% |

88.1% |

| Decisions under uncertainty (incomplete info) |

4.07 |

4 |

0.89 |

2.4% |

9.5% |

88.1% |

| Confident in high-pressure decision scenarios |

3.55 |

3 |

0.96 |

11.9% |

35.7% |

52.4% |

| Anticipate trade-offs before key decisions |

4.40 |

5 |

0.79 |

2.4% |

4.8% |

92.9% |

| Adapt decisions to changing market conditions |

4.17 |

5 |

1.20 |

14.3% |

2.4% |

83.3% |

| Adjust strategies based on feedback/outcomes |

4.31 |

5 |

0.91 |

7.1% |

0% |

92.9% |

| Re-evaluate decisions if new information |

4.57 |

5 |

0.66 |

0% |

4.8% |

95.2% |

| Continuous learning & iteration in decision-making |

4.46 |

5 |

0.70 |

0% |

2.4% |

97.6% |

Students reported broadly positive perceptions regarding the impact of the simulation on their decision-making abilities (

Table 1). The composite mean score for this construct was M = 3.90 (SD = 0.27), and the item-level analysis offers further nuance. Students expressed high agreement that the simulation enhanced their ability to consider multiple alternatives (M = 4.12), anticipate trade-offs (M = 4.40), and re-evaluate decisions when new information emerged (M = 4.57). These results suggest that students developed strong analytical flexibility and iterative thinking, key competencies in managerial decision-making.

Other items demonstrated slightly lower but still favorable scores. For instance, balancing short- and long-term goals (M = 3.69) and maintaining confidence in high-pressure decision contexts (M = 3.55) were areas of comparatively modest self-reported improvement. These findings indicate that while the simulation promoted cognitive and strategic aspects of decision-making, affective components like confidence and ambiguity tolerance may require further scaffolding in future iterations. Still, the overall results suggest that simulations offer a robust platform for students to practice and refine complex business judgments.

Table 2.

Teamwork Skill Development (Likert-scale 1=Strongly Disagree to 5=Strongly Agree, N = 42 per item).

Table 2.

Teamwork Skill Development (Likert-scale 1=Strongly Disagree to 5=Strongly Agree, N = 42 per item).

| Construct & Item (Abbreviated) |

Mean |

Median |

SD |

% Disagree(a) |

% Neutral |

% Agree(b) |

| Teamwork Skill Development |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Communicate effectively with team members |

4.33 |

4 |

0.75 |

2.4% |

4.8% |

92.9% |

| Confident expressing ideas in team discussions |

4.29 |

4 |

0.75 |

2.4% |

4.8% |

92.9% |

| Importance of actively listening to others |

4.36 |

5 |

0.73 |

2.4% |

2.4% |

95.2% |

| Collaborate effectively to achieve common goals |

4.31 |

4 |

0.71 |

0% |

7.1% |

92.9% |

| Coordinate tasks efficiently within a team |

4.52 |

5 |

0.55 |

0% |

0% |

100% |

| Adapt to different team roles as needed |

4.21 |

4 |

0.80 |

2.4% |

7.1% |

90.5% |

| Work with team members of diverse skills/backgrounds |

4.19 |

4 |

0.75 |

0% |

9.5% |

90.5% |

| Balance individual contributions with team goals |

4.26 |

4 |

0.76 |

0% |

9.5% |

90.5% |

| Resolve conflicts and disagreements in team |

4.33 |

4 |

0.70 |

0% |

4.8% |

95.2% |

| Negotiate and compromise in team work |

4.24 |

4 |

0.72 |

0% |

7.1% |

92.9% |

| Confident handling teamwork-related challenges |

4.36 |

4 |

0.73 |

0% |

4.8% |

95.2% |

| Address miscommunication in team environment |

4.14 |

4 |

0.82 |

2.4% |

7.1% |

90.5% |

| Comfortable taking initiative in team setting |

4.43 |

5 |

0.67 |

0% |

2.4% |

97.6% |

| Support and motivate team members |

4.31 |

4 |

0.75 |

0% |

7.1% |

92.9% |

| Accountable for contributions and decisions in team |

4.17 |

4 |

0.82 |

2.4% |

7.1% |

90.5% |

| Importance of trust and dependability in teamwork |

4.48 |

5 |

0.64 |

0% |

2.4% |

97.6% |

Students reported particularly high gains in teamwork competencies (

Table 2). Most teamwork items had mean ratings well above 4.0. For instance,

“The simulation improved my ability to communicate effectively with team members” had a mean of 4.33 (SD = 0.75), and

“I learned how to collaborate effectively with peers to achieve common goals” averaged 4.31 (SD = 0.71). The lowest-rated teamwork item,

“Being accountable for my contributions in a team,” still had M = 4.17 (SD = 0.82), indicating solid agreement.

The response distribution for teamwork items showed very few ratings below 3; nearly all students agreed or strongly agreed that the simulation enhanced their teamwork. This suggests the simulation was highly effective in imparting teamwork skills, consistent with literature that highlights collaboration as a key outcome of experiential learning.

Table 3.

Leadership Skill Development (Likert-scale 1=Strongly Disagree to 5=Strongly Agree, N = 42 per item).

Table 3.

Leadership Skill Development (Likert-scale 1=Strongly Disagree to 5=Strongly Agree, N = 42 per item).

| Construct & Item (Abbreviated) |

Mean |

Median |

SD |

% Disagree(a) |

% Neutral |

% Agree(b) |

| Leadership Skill Development |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Take initiative in leadership roles |

3.98 |

4 |

0.88 |

2.4% |

21.4% |

76.2% |

| Confident guiding team’s strategy & decisions |

4.00 |

4 |

0.87 |

2.4% |

16.7% |

81.0% |

| Proactive in identifying and solving problems |

3.69 |

4 |

0.92 |

7.1% |

42.9% |

50.0% |

| Timely, well-informed decisions in leadership role |

3.79 |

4 |

0.97 |

7.1% |

28.6% |

64.3% |

| Motivate and inspire team members |

3.74 |

4 |

1.03 |

11.9% |

28.6% |

59.5% |

| Provide constructive feedback to improve performance |

3.81 |

4 |

0.97 |

4.8% |

33.3% |

61.9% |

| Delegate tasks effectively (balanced workload) |

3.67 |

4 |

0.99 |

9.5% |

40.5% |

50.0% |

| Resolve conflicts & foster positive team environment |

3.86 |

4 |

1.03 |

14.3% |

21.4% |

64.3% |

| Develop and communicate a clear vision for team |

3.69 |

4 |

0.96 |

7.1% |

42.9% |

50.0% |

| Analyze complex situations & make strategic decisions |

3.93 |

4 |

0.92 |

2.4% |

26.2% |

71.4% |

| Adapt leadership strategies to new challenges |

3.79 |

4 |

0.96 |

4.8% |

35.7% |

59.5% |

| Importance of long-term thinking in leadership |

3.86 |

4 |

0.89 |

2.4% |

33.3% |

64.3% |

| Aware of responsibilities & ethics of being a leader |

3.98 |

4 |

0.85 |

0% |

26.2% |

73.8% |

| Accountability for my decisions/actions as leader |

3.83 |

4 |

0.88 |

2.4% |

31.0% |

66.7% |

| Balance assertiveness with empathy in leadership |

3.43 |

3 |

1.04 |

21.4% |

33.3% |

45.2% |

| Maintain composure & confidence under high-pressure as leader |

3.86 |

4 |

0.85 |

0% |

33.3% |

66.7% |

Leadership development items showed more variability (

Table 3). While students generally agreed that their leadership skills improved, the means ranged from about 3.4 to 4.0. For example, students felt more confident guiding team strategy (M = 4.00, SD = 0.87) and taking initiative in leadership roles (M = 3.98, SD = 0.88). However, aspects like balancing assertiveness with empathy were rated slightly lower (M = 3.43, SD = 1.04), with a notable minority of students responding neutrally or even disagreeing that they improved in this area.

This spread suggests that certain nuanced leadership skills (like emotional balance in leadership) may require more time or targeted intervention to develop. Nonetheless, most leadership items had medians of 4, and a majority indicated improvement across all leadership dimensions. Students recognized gains in skills such as providing constructive feedback (M = 3.81, SD = 0.97) and adapting leadership strategies to new challenges (M = 3.79, SD = 0.96).

Table 4.

Job Market Preparedness (Likert-scale 1=Strongly Disagree to 5=Strongly Agree, N = 42 per item).

Table 4.

Job Market Preparedness (Likert-scale 1=Strongly Disagree to 5=Strongly Agree, N = 42 per item).

| Construct & Item (Abbreviated) |

Mean |

Median |

SD |

% Disagree(a) |

% Neutral |

% Agree(b) |

| Job Market Preparedness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Prepared to handle real-world job challenges / responsibilities |

4.12 |

4 |

0.74 |

0% |

16.7% |

83.3% |

| Understand practical applications of business concepts at work |

4.19 |

4 |

0.68 |

0% |

9.5% |

90.5% |

| Confident analyzing business situations & making decisions in a job role |

4.02 |

4 |

0.72 |

0% |

16.7% |

83.3% |

| Develop ability to prioritize tasks & manage workload in business environment |

4.07 |

4 |

0.72 |

0% |

16.7% |

83.3% |

| Prepared to collaborate and communicate with colleagues professionally |

4.31 |

4 |

0.58 |

0% |

4.8% |

95.2% |

| Developed negotiation and professional discussion skills for workplace |

4.07 |

4 |

0.72 |

0% |

14.3% |

85.7% |

| Improved ability to work in diverse teams (different perspectives/backgrounds) |

4.29 |

4 |

0.67 |

0% |

7.1% |

92.9% |

| Reinforced understanding of importance of networking/relationship-building |

4.00 |

4 |

0.79 |

0% |

21.4% |

78.6% |

| Confident transitioning from academic to professional world |

4.21 |

4 |

0.70 |

0% |

9.5% |

90.5% |

| Enhanced problem-solving skills, making me more employable |

4.24 |

4 |

0.66 |

0% |

7.1% |

92.9% |

| Better understanding of what employers expect from graduates |

4.33 |

4 |

0.65 |

0% |

7.1% |

92.9% |

| Gained hands-on experiences to discuss in job interviews |

3.79 |

4 |

0.85 |

2.4% |

26.2% |

71.4% |

| Learned to adapt quickly to new challenges in fast-changing work environment |

4.02 |

4 |

0.75 |

0% |

16.7% |

83.3% |

| More comfortable learning from mistakes & adjusting approach in professional context |

4.14 |

4 |

0.66 |

0% |

9.5% |

90.5% |

| Developed mindset of continuous learning & self-improvement for career growth |

4.31 |

4 |

0.66 |

0% |

7.1% |

92.9% |

| Greater confidence to take on leadership/decision-making roles in future career |

4.19 |

4 |

0.72 |

0% |

11.9% |

88.1% |

Perceptions of career readiness were quite positive (

Table 4). Students agreed that the simulation prepared them for real-world job challenges (M = 4.12, SD = 0.74) and helped them understand practical applications of business concepts (M = 4.19, SD = 0.68). The highest-rated item was

“I now have a better understanding of what employers expect from graduates in a business-related role,” with M = 4.33 (SD = 0.65), suggesting the simulation provided clarity on employer expectations. Even the relatively lower items, like

“The simulation has given me examples of hands-on experience I can discuss in job interviews,” had a mean of 3.79 (SD = 0.85), indicating slight to moderate agreement. Response distributions showed that for most job preparedness items, over 80% of respondents selected 4 (“Agree”) or 5 (“Strongly Agree”). This aligns with the idea that experiential learning can boost students’ confidence in their employability.

Table 4 details these results, showing a consistent trend of agreement across the board.

As seen in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4, the majority of responses fall in the “Agree” range for most items. Only a few items (particularly in the Leadership domain) have a substantial proportion of neutral or disagree responses. These descriptive findings suggest that students felt the simulation provided broad benefits, especially in teamwork and practical preparedness. Leadership skill development showed slightly more mixed feedback, indicating room for improvement in that area of the simulation.

Despite the generally high means, the internal consistency of the item sets for each construct was lower than expected. Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficients for the 16-item scales were as follows: Decision-Making α = –.05, Teamwork α = –.02, Leadership α = .06, and Job Preparedness α = –.17. These values are far below the conventional acceptable threshold of 0.70, indicating poor reliability for all four scales. In fact, several alphas were negative, which can occur when there is minimal or no true consistency among items (or if different items capture very disparate aspects of a concept). Practically, this means that the items within each supposed construct did not correlate well with each other. Given the low reliability, the composite scores should be interpreted with caution. This issue is revisited in the Discussion section as it may have implications for how we interpret the subsequent hypothesis tests (e.g., unreliable scales can attenuate correlations among constructs).

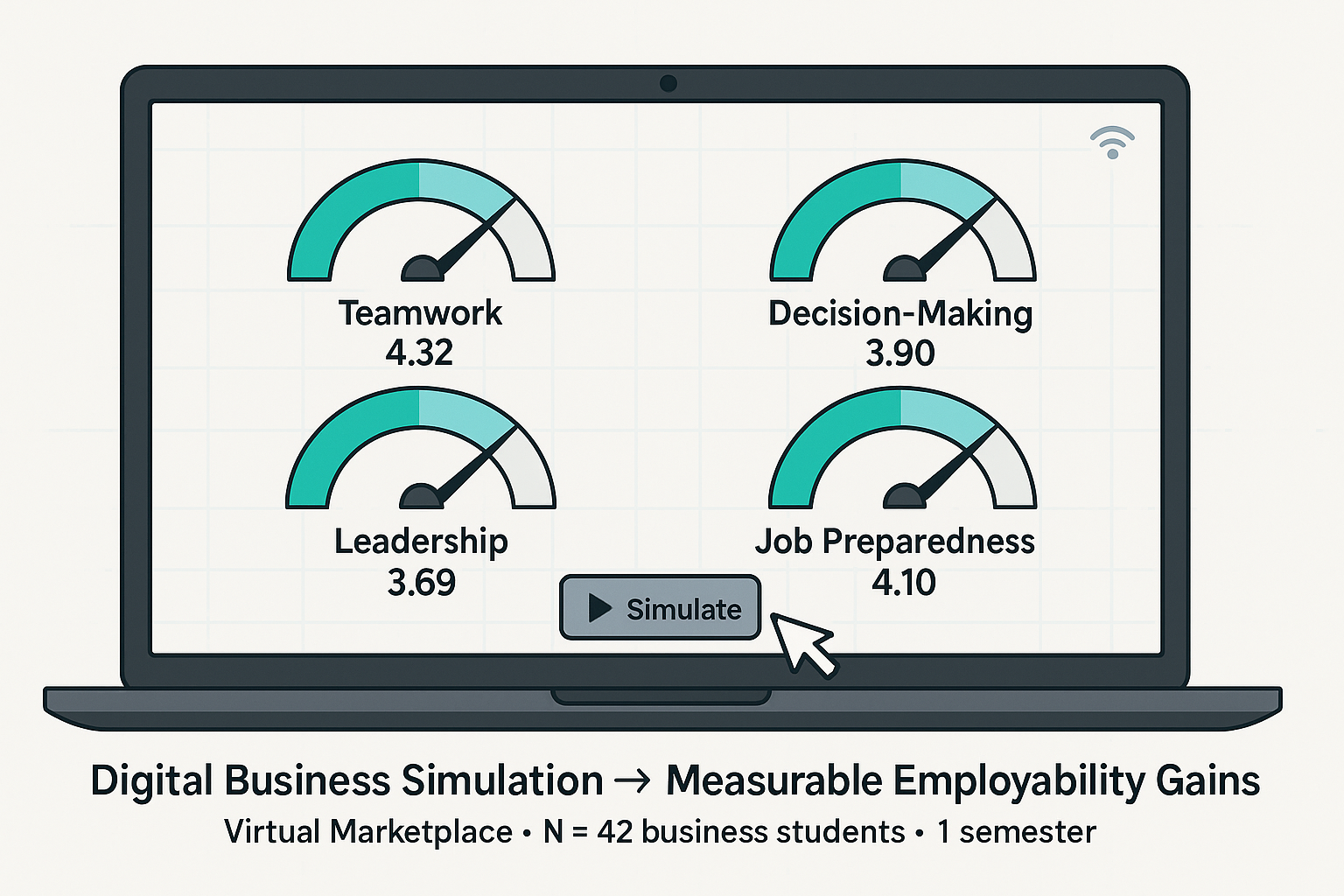

To evaluate hypotheses H1–H4, one-sample

t-tests were conducted to determine whether the mean composite scores for each construct (decision-making, teamwork, leadership, and job market preparedness) significantly exceeded the neutral midpoint of 3.0 (“neither agree nor disagree”) on the 1–5 Likert scale. As summarized in

Table 5, all four constructs demonstrated statistically significant mean scores above the neutral threshold (

p < .001 for all tests), thereby supporting H1 through H4.

Table 5.

One-Sample t-test Results for Composite Scores (H1–H4).

Table 5.

One-Sample t-test Results for Composite Scores (H1–H4).

| Construct |

Mean (SD) |

Test vs. 3 |

t(41) |

p-value |

| Decision-Making Skills |

3.90 (0.27) |

> 3 (Neutral) |

21.36 |

< .001*** |

| Teamwork Skills |

4.32 (0.18) |

> 3 (Neutral) |

47.37 |

< .001*** |

| Leadership Skills |

3.69 (0.28) |

> 3 (Neutral) |

16.17 |

< .001*** |

| Job Market Preparedness |

4.10 (0.20) |

> 3 (Neutral) |

35.65 |

< .001*** |

For decision-making skills, the composite mean (M = 3.90, SD = 0.27) was substantially higher than the midpoint, t(41) = 21.36, p < .001, indicating that students perceived marked improvements in their ability to analyze complex problems and make strategic business decisions post-simulation. Similarly, teamwork skills yielded the highest mean score (M = 4.32, SD = 0.18), with a robust statistical difference from the neutral value, t(41) = 47.37, p < .001, reflecting strong consensus on enhanced collaborative competencies. In contrast, leadership skills exhibited a comparatively modest yet still significant mean increase (M = 3.69, SD = 0.28), t(41) = 16.17, p < .001, suggesting that while students acknowledged growth in leadership capabilities, their self-assessed gains were less pronounced relative to other domains. Finally, job market preparedness scores (M = 4.10, SD = 0.20) were significantly elevated above the midpoint, t(41) = 35.65, p < .001, underscoring participants’ confidence in their readiness to navigate workplace challenges and transition effectively into professional roles following the simulation.

These results collectively affirm the digital simulation’s efficacy in fostering self-perceived skill development across all targeted areas, with particularly strong effects observed for teamwork and career readiness outcomes.

As shown in

Table 5, the t-tests confirm that in all areas students’ self-assessments were significantly above “neither agree nor disagree.” In practical terms, participants on average agreed that the simulation had improved their decision-making, teamwork, leadership, and their readiness for the job market. These findings align with prior research suggesting that simulation-based learning can bolster confidence and competence in key employability skills.

To examine H5, we first looked at bivariate Pearson correlations among the four composite variables (

Table 6). We expected that improvements in decision-making, teamwork, and leadership might be positively interrelated and also correlate with perceived job preparedness. Surprisingly, the correlation analysis did not reveal any significant positive relationships. In fact, all pairwise correlations were very close to zero and none reached statistical significance (p > .40 in all cases).

Table 6.

Pearson Correlations Among Composite Scores (N = 42).

Table 6.

Pearson Correlations Among Composite Scores (N = 42).

| Composite Variable |

Decision-Making |

Teamwork |

Leadership |

Job Preparedness |

| Decision-Making Skills |

— |

|

|

|

| Teamwork Skills |

–.13 |

— |

|

|

| Leadership Skills |

–.12 |

–.03 |

— |

|

| Job Market Preparedness |

.08 |

.06 |

.01 |

— |

Table 6 presents the correlation matrix. Notably, the correlation between each skill-development construct and job preparedness was weak:

r = .08 for Decision-Making–Job Prep,

r = .06 for Teamwork–Job Prep, and

r = .01 for Leadership–Job Prep, all

ns (not significant). The inter-correlations among the three skill constructs themselves were also near zero (Decision-Making vs Teamwork

r = –.13, Decision vs Leadership

r = –.12, Teamwork vs Leadership

r = –.03, all

ns). These near-zero correlations indicate that students’ ratings of improvement in one area had little to no linear relationship with their ratings in another area. In other words, a student who reported a high gain in teamwork skills was not necessarily the same student who reported a high gain in decision-making or leadership, and vice versa.

Given the lack of significant correlations, we proceeded to the multiple linear regression (H5) with some expectation that the combined predictors might not explain much variance in job preparedness. The regression model used Job Market Preparedness as the dependent variable and Decision-Making, Teamwork, and Leadership composite scores as simultaneous independent variables. The overall regression was not significant,

F(3, 38) = 0.15,

p = .928, with an R² of .012 (i.e., only about 1.2% of the variance in job readiness was explained by the three predictors).

Table 7 summarizes the regression coefficients. Consistent with the correlation results, none of the three skill development constructs had a significant unique effect on job preparedness in the presence of the others. Decision-Making (β = 0.07,

p = .57), Teamwork (β = 0.08,

p = .67), and Leadership (β = 0.01,

p = .91) all had very small, nonsignificant standardized coefficients. The unstandardized coefficients were likewise close to zero (B = 0.07 for Decision, 0.08 for Teamwork, 0.01 for Leadership).

Table 7.

Multiple Linear Regression Predicting Job Market Preparedness (H5).

Table 7.

Multiple Linear Regression Predicting Job Market Preparedness (H5).

| Predictor |

B |

SE(B) |

β (Standardized) |

t(38) |

p-value |

| (Constant) |

3.446 |

1.093 |

— |

3.153 |

.003** |

| Decision-Making Skills |

0.069 |

0.121 |

0.07 |

0.573 |

.570 |

| Teamwork Skills |

0.078 |

0.181 |

0.08 |

0.428 |

.671 |

| Leadership Skills |

0.014 |

0.117 |

0.01 |

0.121 |

.905 |

As shown in

Table 7, none of the independent variables in the regression significantly predicted the dependent variable of job preparedness. H5 was not supported; the data did not show that gains in decision-making, teamwork, or leadership skills translated into higher self-rated career readiness (at least not in a linear additive way captured by this model). This result was unexpected, given that one might assume improvements in those skill areas would contribute to feeling more prepared for the job market. We explore possible reasons for this finding in the Discussion.

5. Discussion

This study examined the impact of a digital business simulation on students’ development of decision-making, teamwork, and leadership skills, as well as their overall preparedness for the job market. The descriptive results indicate that students perceived substantial benefits from the simulation across all targeted areas. On average, participants agreed that the experience improved their ability to analyze complex problems, work effectively in teams, lead others, and transition to real-world business environments.

Hypotheses H1–H4 were supported, as all mean scores were significantly above the neutral midpoint, confirming that the simulation was associated with positive self-reported learning outcomes in each domain. This is consistent with prior literature suggesting that simulations can cultivate critical thinking, collaboration, and confidence in applying business knowledge. For instance, Iipinge et al. [

25] found that students in a business simulation developed a range of work-integrated learning skills including teamwork, leadership, analytical thinking, and accountability, which aligns closely with our findings of perceived improvements in those areas. Similarly, experiential learning researchers have noted that engaging in realistic scenarios allows students to practice decision-making and problem-solving in a way that boosts their confidence for actual job tasks [

15,

26,

27]. Our results reinforce these points: students felt more confident in handling business decisions and working with others after the simulation, presumably because they had “hands-on” practice bridging theory and practice.

However, the results for H5 (the relationships among these gains) were not as straightforward. We did not find evidence that improvements in decision-making, teamwork, and leadership were correlated with each other, nor that they predicted improvements in job market preparedness. In other words, a student’s rating of their own skill growth in one area did not reliably coincide with their rating in another area. This lack of correlation is intriguing, as one might expect that a generally effective simulation would elevate all skills together for a given student. There are several possible interpretations for this outcome.

It’s possible that students engaged with the simulation in varying ways, leading them to develop certain skills more than others. For example, some students may have taken on a leadership role within their team, thereby experiencing a greater boost in leadership skills but perhaps not as much in other areas. Others might have focused on analytical tasks (improving decision-making) or on group coordination (improving teamwork). As a result, individual learning profiles could differ, yielding low inter-correlations across participants. The open-ended responses support this idea qualitatively: one student mentioned refining their analytical approach to decision-making, while another emphasized becoming more confident in team settings. These divergent takeaways suggest the simulation allowed students to personalize their learning focus.

The very low Cronbach’s alpha values indicate that the items within each scale were not highly consistent. Poor reliability attenuates observed correlations; essentially, a lot of measurement “noise” can mask the true relationship between constructs. It may be that there is an underlying positive relationship among these skill gains, but our measurement instruments were not precise enough to detect it. For example, if the teamwork scale included various subskills (communication, conflict resolution, accountability, etc.) that did not move in unison for every student, the aggregate score becomes a noisy indicator. Future studies should consider refining the survey instruments, perhaps by focusing on more homogeneous subsets of items or by increasing the number of respondents to get more stable estimates. It is also possible some items needed reverse-coding or belonged to sub-dimensions that were not accounted for, which could depress alpha if not handled correctly.

Many of the item means were quite high (often above 4 on a 5-point scale), which suggests a potential ceiling effect. If most students already rate themselves near the top for certain skills, there might be limited variance to correlate with other constructs. In our sample, teamwork in particular was almost unanimously high for everyone (with several items where 100% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed they improved). With such low variability, even if teamwork was genuinely linked to job preparedness, the correlation coefficient would be small. In short, when everyone has similarly high scores, it’s hard to see a statistical relationship. This could imply that the simulation was broadly effective for all, leaving little differentiation among students; a positive outcome educationally, though one that complicates correlational analysis.

Another interpretation for the non-significant prediction of job preparedness is that students might not immediately connect their gains in specific skills to their overall career readiness. It may require additional reflection or instruction to help students see, for example, how improved decision-making or leadership in a classroom simulation translates to being better prepared for a job. If students compartmentalized these as separate insights, they might rate each skill highly but not integrate them into a holistic sense of career confidence. Educators could address this by debriefing simulations in a way that explicitly ties skill development to employability (e.g., discussing how simulation experiences can be articulated in job interviews or applied in future workplace scenarios). This kind of guided reflection could strengthen the link between skill gains and career readiness perceptions.

In light of these points, H5 was not supported by our data. The initial expectation (that decision-making, teamwork, and leadership improvements would positively correlate with each other and collectively enhance job readiness) did not materialize. Interestingly, this diverges from some prior expectations in the literature. For instance, competency frameworks for career readiness often assume that leadership and teamwork go hand-in-hand as complementary skills that together improve employability. Our findings suggest the relationship may be more complex or may require certain conditions to emerge (such as effective integration of learning or high fidelity measures). It’s worth noting that while our participants all went through the same simulation, their personal experiences of it were not uniform in focus, which might explain why gains did not cluster neatly.

Despite the unexpected lack of correlation among skill domains, the overall positive outcomes in each area have practical significance. The high mean scores for skill improvements indicate that business simulations can be a valuable tool in higher education for building soft skills relevant to the workplace. Students felt more capable of critical thinking, collaboration, and leadership after the exercise; all qualities that employers highly value in new graduates. From an instructional design perspective, our results support the inclusion of simulation-based learning in business curricula to enhance career readiness. The simulation provided students with concrete experiences they can draw upon in future job settings, echoing the sentiment that such experiences give students a “leading edge in job interviews and in the workplace”. In practice, universities might use these findings to justify investment in simulation software or to partner with organizations to create realistic experiential learning opportunities.

However, to maximize the benefits, educators should safeguard that these digital simulations are structured and debriefed in ways that produce coherent learning across different skill sets. The low internal consistency of the survey responses suggests that students might benefit from more integrated or guided learning objectives. In the future, facilitators could, for example, include specific reflection sessions where students discuss how their decision-making process affected team outcomes, or how taking leadership roles influenced their overall success in the simulation. By making these connections explicit, students may develop a more unified improvement across competencies. Additionally, if the goal is to improve “career readiness” as a distinct outcome, instructors might incorporate discussions on how each skill area (decision-making, teamwork, leadership) directly relates to workplace effectiveness; helping students form a mental model of these skills as part of an integrated career toolkit rather than siloed abilities.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the sample size (42 students from one program) limits the generalizability of the findings. The results may not extend to other contexts (e.g., different universities, younger students, or simulations in other disciplines). Second, all data were self-reported immediately after the simulation. Thus, responses could be subject to positivity bias (students might feel compelled to report improvement) or might reflect short-term impressions rather than long-term skill acquisition. Future research could include pre- and post-test comparisons or objective performance metrics to supplement self-assessments. Third, as discussed, the measurement scales we used were not validated and showed poor internal consistency. This raises concerns about the precision of the conclusions, especially regarding the relationships among constructs. Developing or using validated scales for assessing skill gains (perhaps fewer items with clearer focus, or separating sub-constructs) would improve future studies. Finally, the cross-sectional design (measuring everything at one time point) means we cannot conclusively infer the degree to which the simulation caused the reported improvements; although it was part of the course design, there’s always a possibility that other factors (like concurrent coursework or team dynamics) influenced students’ self-evaluations.

Building on this study, future research could explore ways to strengthen and verify the link between simulation experiences and career readiness. For example, a longitudinal study could track students into internships or first jobs to see if those who went through simulations perform or adapt better in early career tasks. It would also be valuable to experiment with simulation designs to target leadership development more effectively, as our participants showed comparatively lower gains there. Incorporating mentorship or feedback from industry professionals into the simulation might enhance the leadership learning aspect and make it more consistent. Additionally, research could investigate if certain individual differences (personality, prior experience, etc.) cause some students to benefit more in one area versus another during simulations. Understanding these patterns could help educators tailor the experience or provide supplemental support to ensure balanced development.

6. Conclusion

This study explored the efficacy of digital business simulations in higher education, focusing on their impact on students' decision-making, teamwork, leadership skills, and overall job market preparedness. The findings demonstrate that such simulations are a powerful tool for bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical skill development, aligning with the growing emphasis on digital education technologies. Students reported significant improvements across all targeted skill domains, with particularly strong gains in teamwork and job preparedness. However, the study also revealed a critical insight: while skill development was evident, no correlations were found between these domains, nor did they collectively predict job preparedness. This suggests that learning outcomes are differentiated rather than integrated, highlighting a disconnect between skill gains and holistic career readiness.

The analysis revealed that students perceived substantial benefits from participating in the business simulation. Decision-making skills showed marked improvement, with students gaining confidence in analyzing complex problems and making strategic choices. Teamwork skills emerged as the area of greatest growth, reflecting the collaborative nature of the simulation. Leadership skills, while still showing positive development, exhibited more variability, suggesting that certain nuanced aspects of leadership may require additional scaffolding. Notably, students felt significantly more prepared for the job market, yet improvements in individual skills did not correlate with one another or directly contribute to overall career readiness. This finding underscores the need for structured debriefing and reflection to help students synthesize their learning into a cohesive professional identity.

The study highlights the transformative potential of digital business simulations in higher education while also revealing an important limitation: skill development occurs in isolated domains rather than as an interconnected competency framework. This has significant implications for curriculum design, suggesting that simulations alone may not be sufficient to ensure holistic career readiness. Educators must integrate structured debriefing sessions that explicitly connect skill gains to workplace applicability, helping students recognize how decision-making, teamwork, and leadership function synergistically in professional settings.

The results suggest several practical applications for digital business simulations. Universities and business schools can incorporate these tools into their curricula but should complement them with guided reflection exercises to maximize integration. For example, post-simulation discussions could focus on how leadership decisions influenced team dynamics or how analytical skills contributed to strategic outcomes. Additionally, simulations could be enhanced with real-world case studies or employer feedback to reinforce the connection between classroom learning and job expectations. Policymakers and industry partners should support these efforts by funding interdisciplinary projects that align simulation design with labor market demands.

Future research should investigate why skill gains remain compartmentalized rather than interconnected. Longitudinal studies could assess whether structured debriefing or mentorship interventions improve the integration of skills into career readiness. Comparative analyses of different simulation designs, such as those incorporating real-time employer feedback versus purely academic models, could identify best practices for fostering holistic competency development. Additionally, exploring the role of metacognition in simulation-based learning may help students better internalize and apply their skills in professional contexts.

This study has several limitations, including its small sample size, reliance on self-reported data, and cross-sectional design. The lack of correlation among skill domains may also stem from measurement limitations, as the survey scales exhibited low internal consistency. Future research should employ validated instruments and mixed-method approaches (e.g., combining surveys with behavioral assessments) to capture skill integration more accurately. Despite these constraints, the study provides valuable insights into both the strengths and gaps of simulation-based learning.

In conclusion, this research affirms the value of digital business simulations as a high-impact pedagogical tool while also revealing a critical gap: skill development does not automatically translate into integrated career readiness. To maximize their effectiveness, simulations must be paired with structured reflection and real-world contextualization. By refining digital simulation design and embedding deliberate debriefing practices, educators can ensure that students not only acquire individual skills but also learn to apply them cohesively in professional settings. As digital education evolves, this study underscores the need for a more strategic approach to experiential learning, one that bridges the divide between skill acquisition and employability. Future efforts should prioritize interventions that foster synthesis, ensuring that graduates enter the workforce not just with competencies, but with the ability to wield them synergistically.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.F.M. and J.S.; methodology, H.F.M.; validation, H.F.M. and J.S.; formal analysis, H.F.M. and J.S.; investigation, H.F.M. and J.S.; data curation, H.F.M. and J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.F.M. and J.S.; writing—review and editing, H.F.M. and J.S.; funding acquisition, H.F.M. and J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and the APC was funded by the Lisbon Accounting and Business School (ISCAL), Polytechnic University of Lisbon / Instituto Superior de Contabilidade e Administração de Lisboa, Instituto Politécnico de Lisboa.

Informed Consent Statement

Participants in this study provided verbal informed consent prior to participating in the surveys. They were informed about the purpose of the research, the voluntary nature of their participation, and the anonymity of their responses. Since the surveys were conducted anonymously, no personally identifiable information was collected, and participants were assured that their responses would be used solely for research purposes. Consent included permission to analyze and publish the anonymized data. No photos, images, or other identifying materials were collected as part of this study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We thank the students from the Lisbon Accounting and Business School (ISCAL) who generously volunteered their time and insights to participate in this study. Their engagement and feedback were invaluable in shaping the findings of this research. We also sincerely thank the Languages Department of ISCAL for their meticulous language editing and proofreading support, which greatly enhanced the clarity and quality of this article. Their expertise and attention to detail were instrumental in refining the manuscript. Finally, we appreciate the encouragement and constructive feedback from our colleagues, whose insights strengthened this work. This research would not have been possible without the collective support of all those involved.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BSGs |

Business Simulation Games |

| ISCAL |

Lisbon Accounting and Business School, Polytechnic University of Lisbon |

| NACE |

National Association of Colleges and Employers |

| N |

Sample Size (Number of participants) |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| α |

Cronbach’s alpha (a measure of internal consistency/reliability) |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- Judd, B.; Brentnall, J.; Phillips, A.; Aley, M. The practice of simulations as work-integrated learning. In The Routledge International Handbook of Work-integrated Learning; Billett, S., Harteis, C., Gruber, H., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2023; pp. 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Shan, H.; Meek, S. Enhancing graduates’ enterprise capabilities through work-integrated learning in co-working spaces. High. Educ. 2022, 84, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chad, P. Equitable work-integrated-learning: Using practical simulations in university marketing subjects. Australas. Mark. J. 2020, 28, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, T.; Stoica, M. Employer’s perception of new hires: What determines their overall satisfaction with recent graduates? J. Res. Bus. Educ. 2023, 63, 6–23. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, A.M.; Parayitam, S. Employers’ ratings of importance of skills and competencies college graduates need to get hired: Evidence from the New England region of USA. Educ. Train. 2019, 61, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, H.F. Mastering the Game: A Reference Handbook on Business Simulations; LABS - Information and Communication Sciences: Lisbon, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, H.F. The use of a business simulation game in a management course. In Handbook of Research on Serious Games as Educational, Business and Research Tools; Cruz-Cunha, M., Ed.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.K. Innovative experiential learning experience: Pedagogical adopting Kolb’s learning cycle at higher education in Hong Kong. Cogent Educ. 2019, 6, 1644720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development, 2nd ed.; FT Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Velez, A.; Alonso, R.K. Business simulation games for the development of decision making: A systematic review. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.; Bell, H. Applying educational theory to develop a framework to support the delivery of experiential entrepreneurship education. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2020, 27, 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maftuh, M.S.J. Understanding learning strategies: A comparison between contextual learning and problem-based learning. Educazione 2023, 1, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverie, D.A.; Hass, A.; Mitchell, C. Experiential learning: A study of simulations as a pedagogical tool. Mark. Educ. Rev. 2022, 32, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja, V. Simulations in business education: Unlocking experiential learning. In Practices and Implementation of Gamification in Higher Education; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, N.; Chadhar, M.; Goriss-Hunter, A.; Stranieri, A. Business simulation games in higher education: A systematic review of empirical research. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 2022, 1578791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chulkov, D.; Wang, X. The educational value of simulation as a teaching strategy in a finance course. e-J. Bus. Educ. Scholarsh. Teach. 2020, 14, 40–56. [Google Scholar]

- Siewiorek, A.; Saarinen, E.; Lainema, T.; Lehtinen, E. Learning leadership skills in a simulated business environment. Comput. Educ. 2012, 58, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, S.; Costa Oliveira, H.; Barros, T.; de Sá, M. Soft Skills Developed in Business Simulation Models for Accounting - Students’ Perception. INTED2024 Proc. 2024, 2095–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterková, J.; Repaská, Z.; Prachařová, L. Best practice of using digital business simulation games in business education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmuck, R. Education and training of manufacturing and supply chain processes using business simulation games. Procedia Manuf. 2021, 55, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE). The attributes employers look for on new grad résumés and how to showcase them. NACE Press 2025. Available online: https://www.naceweb.org (accessed on day month year).

- Lim, Y.P.; Loh, K.H.; Chiew, T.G.E.; Teh, E.Y.; Yap, J.H. Investigating the effectiveness of business simulation to inculcate lifelong learning amongst learners. Tuijin Jishu/J. Propuls. Technol. 2024, 45, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Lara, A.B.; Serradell-López, E.; Fitó-Bertran, À. Students’ perception of the impact of competences on learning: An analysis with business simulations. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 101, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iipinge, S.E.; Batholmeus, P.N.; Pop, C. Using simulations to improve skills needed for work-integrated learning before and during COVID-19 in Namibia. Int. J. Work-Integr. Learn. 2020, 21, 531–543. [Google Scholar]

- Adib, H. Experiential learning in higher education: Assessing the role of business simulations in shaping student attitudes towards sustainability. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2024, 22, 100968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerridge, C. Experiential learning: Use of business simulations. In Learning and Teaching in Higher Education; Lea, M., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).