Submitted:

08 May 2025

Posted:

09 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Germination Parameters

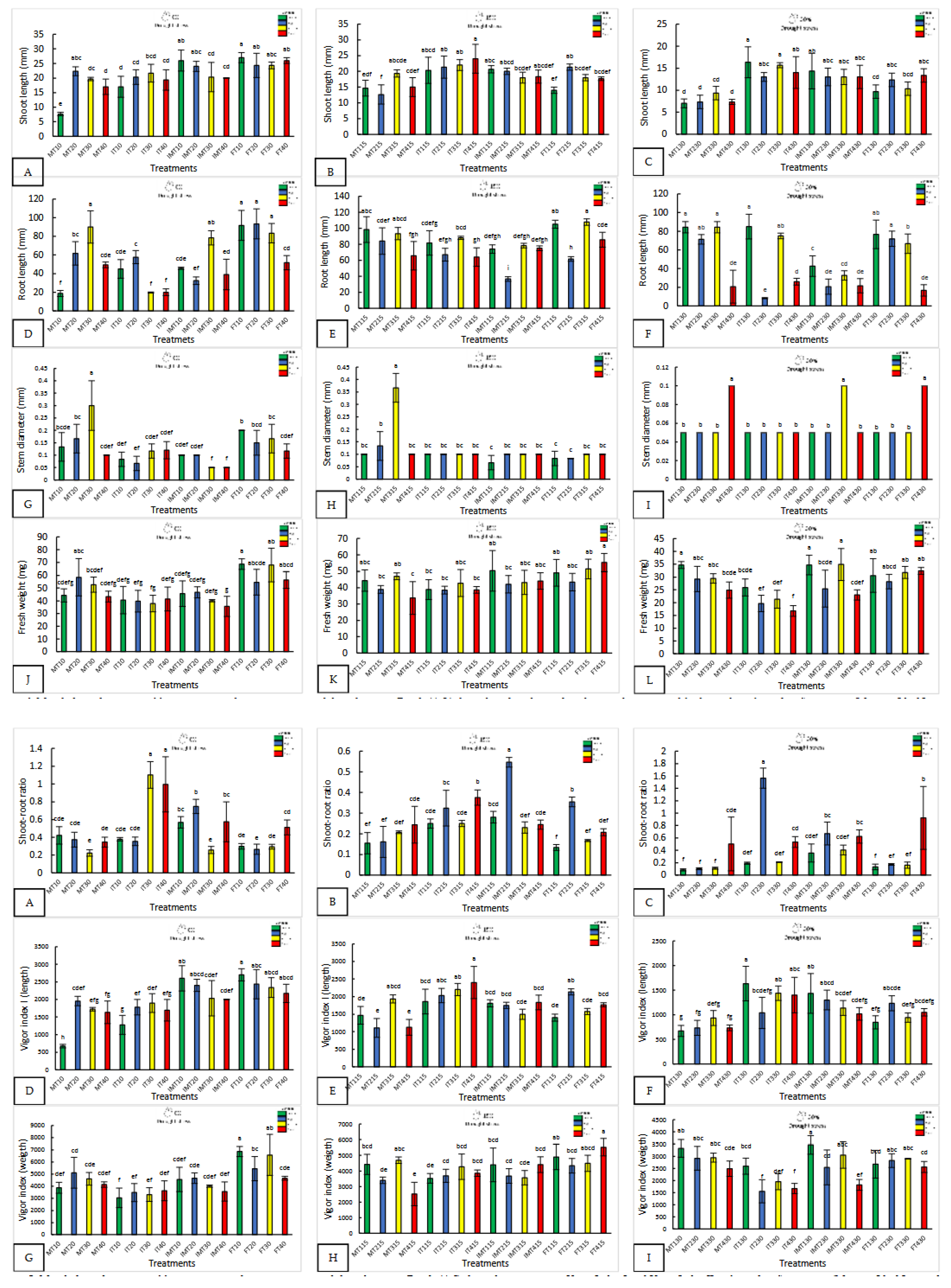

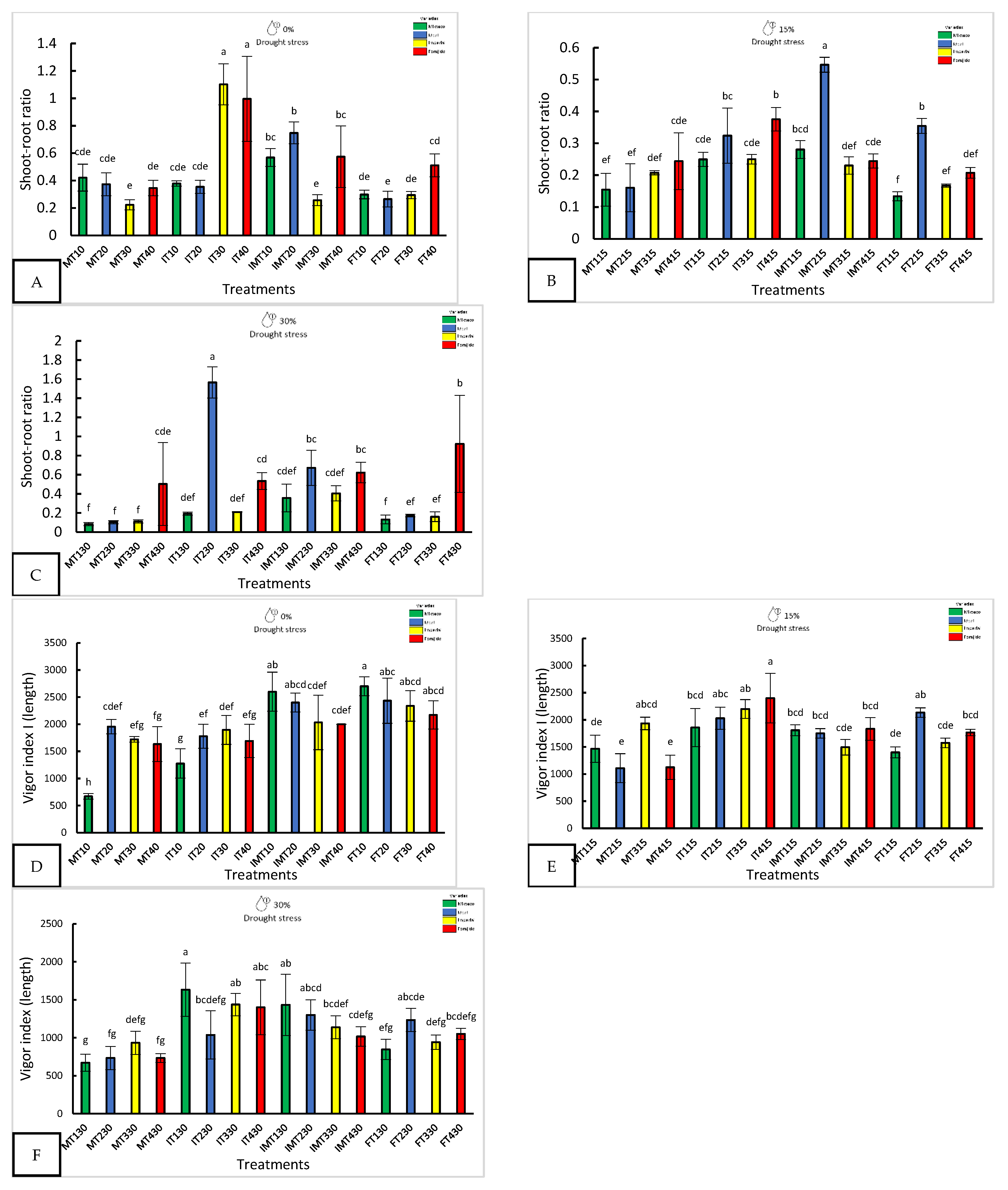

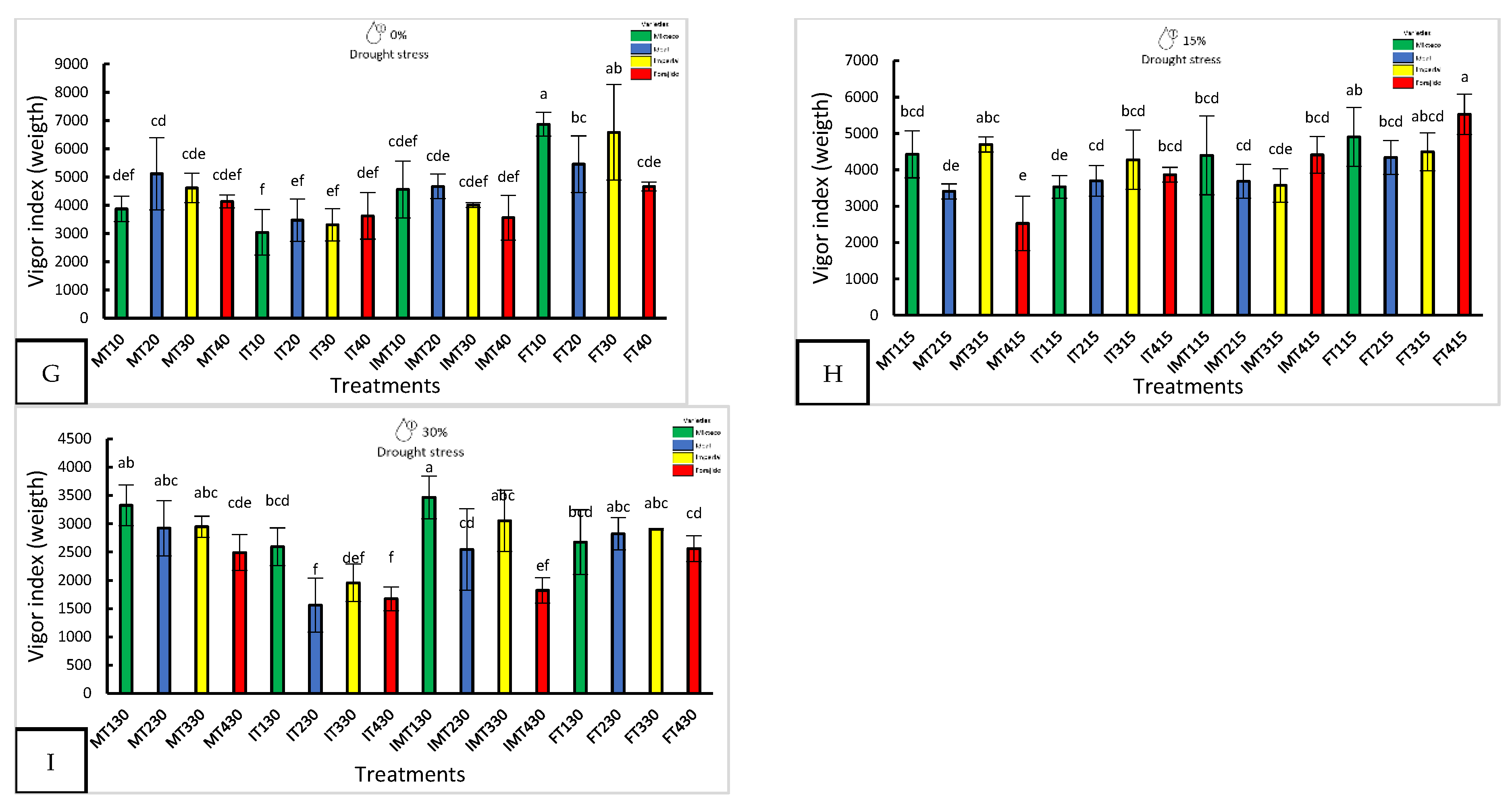

2.2. Morphological Parameters

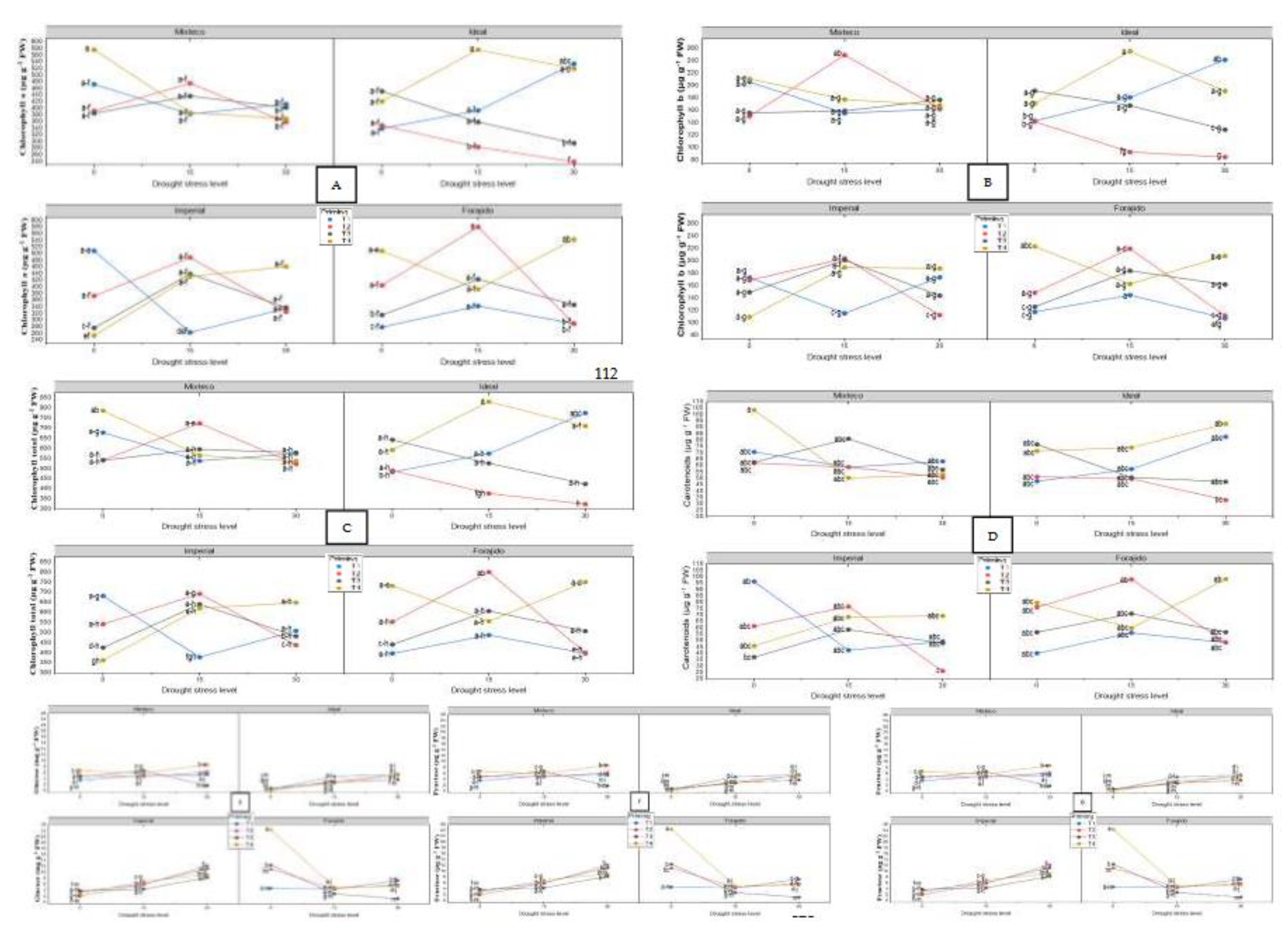

2.3. Biochemical Parameters

2.3.1. Photosynthetic Pigments

2.3.2. Soluble Sugars

2.3.3. Free Proline

2.3.4. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

2.3.5. Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

2.3.6. DPPH Antioxidant Activity

2.4. PCA and Heat Map Analyses

2.4.1. PCA and Heatmap Under 0% Stress

2.4.2. PCA and Heatmap under 15% Stress

2.4.3. PCA and Heatmap under 30% Stress

2.5. Radar Chart: Multivariate Comparison by Drought Level

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

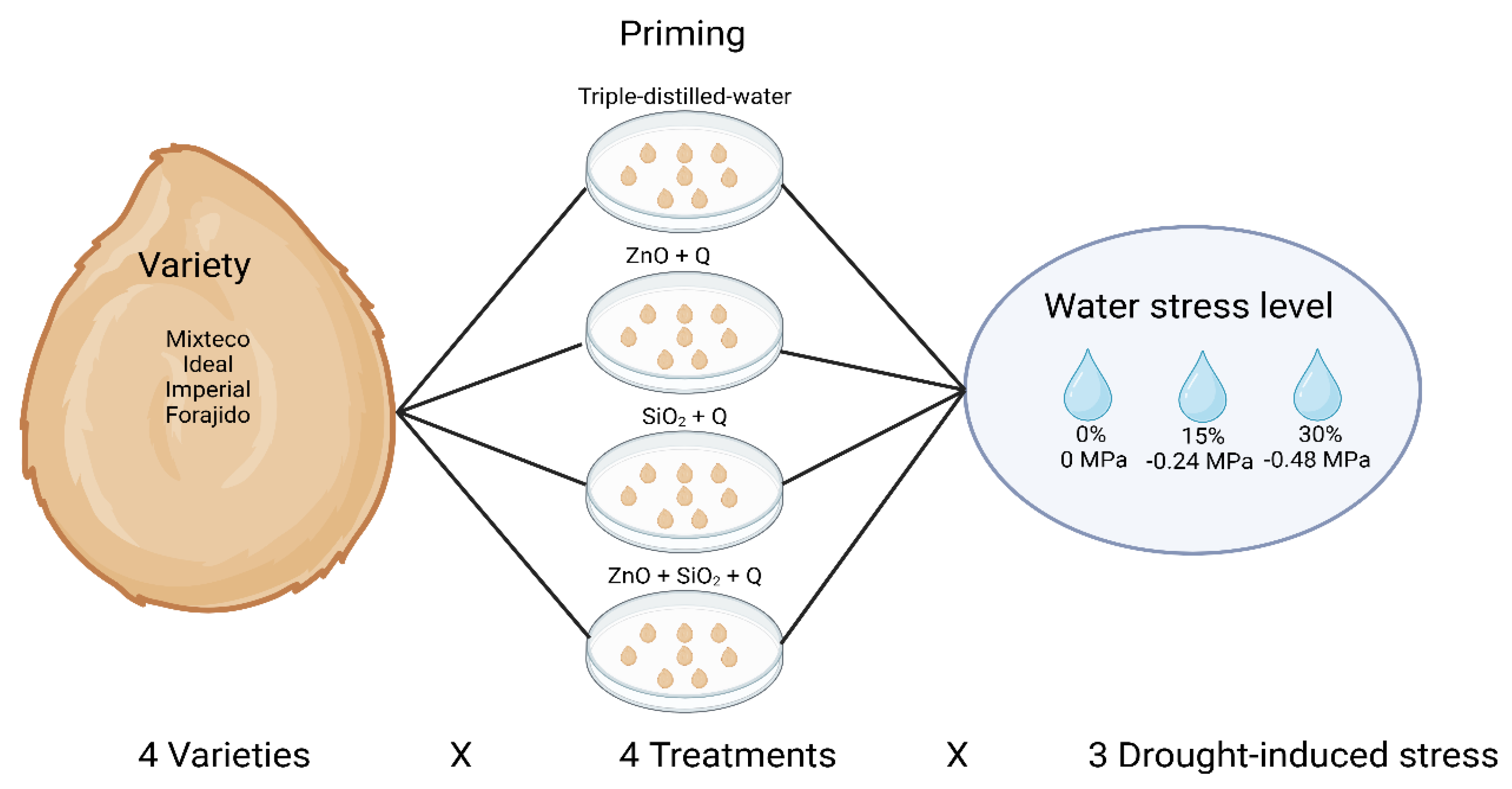

4.1. Experimental Conditions and Plant Material

4.2. Nanoparticle Preparation and Priming Treatments

4.3. Experimental Design

4.4. Drought-Induced Stress

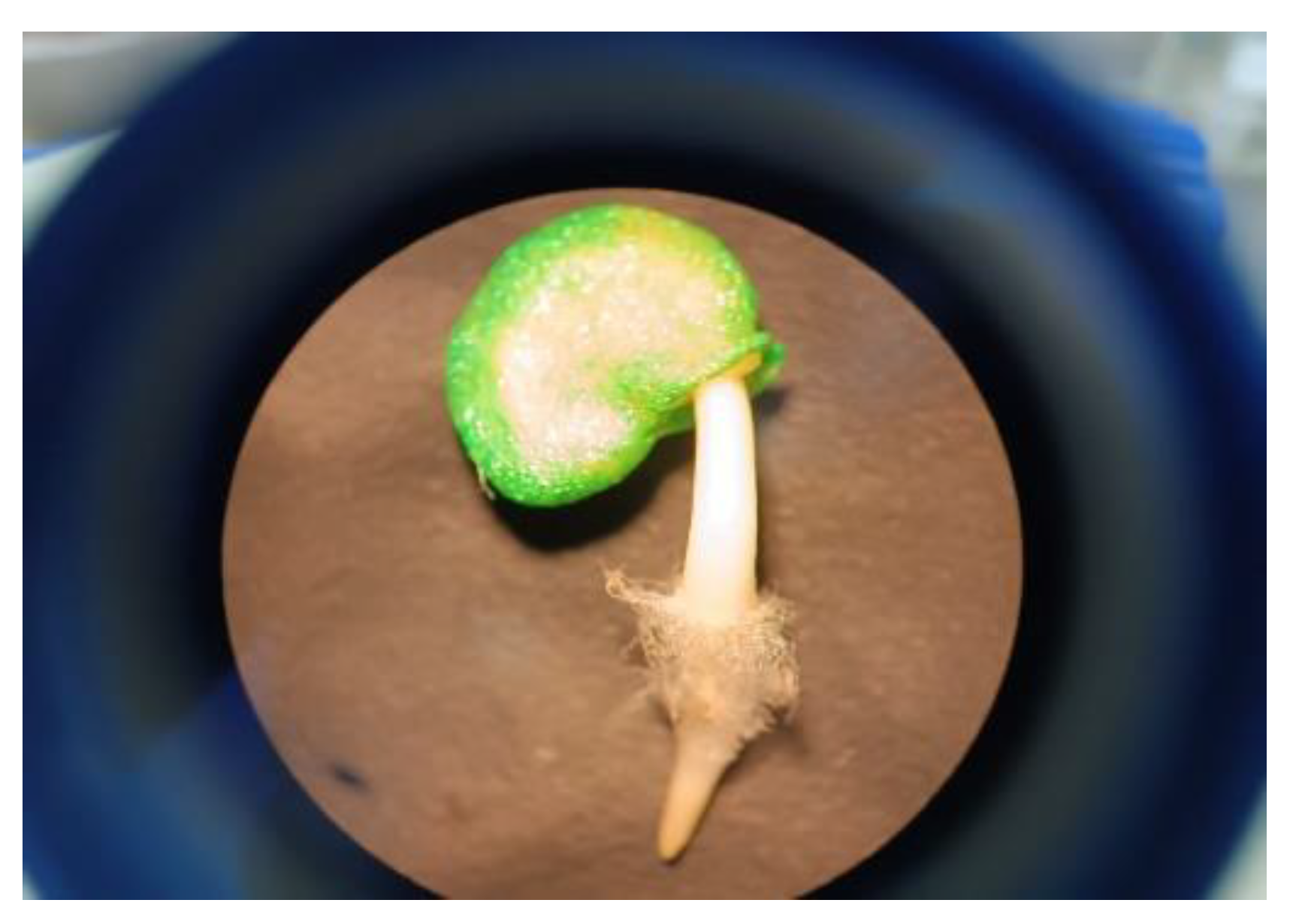

4.5. Germination Assay

4.6. Morphological Measurements

4.7. Biochemical Analyses

4.8. Multivariate and Correlation Analysis

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dietz, K.J.; Zörb, C.; Geilfus, C.M. Drought and crop yield. Plant Biol. 2021, 23, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai-Kalal, P.; Tomar, R.S.; Jajoo, A. Seed nanopriming by silicon oxide improves drought stress alleviation potential in wheat plants. Funct. Plant Biol. 2021, 48, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Figueroa, K.I.; Sánchez, E.; Ramírez-Estrada, C.A.; Anchondo-Páez, J.C.; Ojeda-Barrios, D.L.; Pérez-Álvarez, S. Efficacy and Differential Physiological–Biochemical Response of Biostimulants in Green Beans Subjected to Moderate and Severe Water Stress. Crops 2024, 4, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Li, J.; Wang, C.; Monshi, F.I.; Tabassum, R.; Islam, M.A.; Faruquee, M.; Muktadir, M.A.; Mia, M.S.; Islam, A.K.M.M.; Hasan, A.K.; Sikdar, A.; Feng, B. Enhanced antioxidant activity and secondary metabolite production in tartary buckwheat under polyethylene glycol (PEG)-induced drought stress during germination. Agronomy 2024, 14, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, F.; Kuromori, T.; Urano, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. Drought stress responses and resistance in plants: From cellular responses to long-distance intercellular communication. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 556972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, S.; Ansari, S.A.; Ansari, M.I.; Fujita, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Abiotic stress and reactive oxygen species: Generation, signaling, and defense mechanisms. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadaoui, W.; Tarchoun, N.; Msetra, I.; Pavli, O.; Falleh, H.; Ayed, C.; Amami, R.; Ksouri, R.; Petropoulos, S.A. Effects of drought stress induced by D-mannitol on the germination and early seedling growth traits, physiological parameters and phytochemicals content of Tunisian squash (Cucurbita maxima Duch.) landraces. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1215394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, M.; Hong, C.; Jiao, Y.; Hou, S.; Gao, H. Impacts of drought on photosynthesis in major food crops and the related mechanisms of plant responses to drought. Plants 2024, 13, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ievinsh, G. Water content of plant tissues: So simple that almost forgotten? Plants 2023, 12, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertuş, M.M.; Yazıcılar, B. CaO nanoparticle enhances the seedling growth of Onobrychis viciifolia under drought stress via mannitol use. Biologia 2023, 78, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaf, M.A.; Hao, Y.; He, C.; Mumtaz, M.A.; Shu, H.; Fu, H.; Wang, Z. Physiological and biochemical responses of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) seedlings to nickel toxicity. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 950392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Vásquez, R.; Vera-Guzmán, A.M.; Carrillo-Rodríguez, J.C.; Pérez-Ochoa, M.L.; Aquino-Bolaños, E.N.; Alba-Jiménez, J.E.; Chávez-Servia, J.L. Bioactive and nutritional compounds in fruits of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) landraces conserved among indigenous communities from Mexico. AIMS Agric. Food 2023, 8, 832–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozada, D.N.; Pulicherla, S.R.; Holguin, F.O. Widely targeted metabolomics reveals metabolite diversity in jalapeño and serrano chile peppers (Capsicum annuum L.). Metabolites 2023, 13, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaña, V.; Herrera, E.; Ábrego-Góngora, C.J.; Ávalos, J.A. Socioeconomic drought in a Mexican semi-arid city: Monterrey Metropolitan Area, a case study. Front. Water 2021, 3, 579564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Treviño, S.; Manzano-Camarillo, M.G. The socioeconomic dimensions of water scarcity in urban and rural Mexico: A comprehensive assessment of sustainable development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Sengar, R.S.; Sharma, R.; Rajput, P.; Singh, A.K. Nano-priming technology for sustainable agriculture. Biogeosyst. Tech. 2021, 8, 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Tamindžić, G.; Azizbekian, S.; Miljaković, D.; Ignjatov, M.; Nikolić, Z.; Budakov, D.; Vasiljević, S.; Grahovac, M. Assessment of various nanoprimings for boosting pea germination and early growth in both optimal and drought-stressed environments. Plants 2024, 13, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.F.; Bukhari, M.A.; Raza, M.A.S.; Abbasi, G.H.; Ahmad, Z.; Alqahtani, M.D.; Almutairi, K.F.; Abd_Allah, E.F.; Iqbal, M.A. Enhancing drought tolerance in wheat cultivars through nano-ZnO priming by improving leaf pigments and antioxidant activity. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharf-Eldin, A.A.; Alwutayd, K.M.; El-Yazied, A.A.; El-Beltagi, H.S.; Alharbi, B.M.; Eisa, M.A.M.; Alqurashi, M.; Sharaf, M.; Harbi, N.A.; Al-Qahtani, S.M.; Ibrahim, M.F.M. Response of maize seedlings to silicon dioxide nanoparticles (SiO₂NPs) under drought stress. Plants 2023, 12, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Hayat, Q.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Wani, A.S.; Pichtel, J.; Ahmad, A. Role of proline under changing environments: A review. Plant Signal. Behav. 2012, 7, 1456–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratyusha, S. Phenolic compounds in the plant development and defense. In Plant Stress Physiology: Perspectives in Agriculture; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022; p. 125. [Google Scholar]

- Waqas Mazhar, M.; Ishtiaq, M.; Hussain, I.; Parveen, A.; Hayat Bhatti, K.; Azeem, M.; Thind, S.; Ajaib, M.; Maqbool, M.; Sardar, T. Seed nano-priming with zinc oxide nanoparticles in rice mitigates drought and enhances agronomic profile. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez Suárez, L.; Álvarez Fonseca, A.; Ramírez Fernández, R. Aspectos de interés sobre las acuaporinas en las plantas. Cultiv. Trop. 2014, 35, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkavand, P.; Tabari, M.; Zarafshar, M.; Tomášková, I.; Struve, D. Effect of SiO₂ nanoparticles on drought resistance in hawthorn seedlings. Leśne Pr. Badawcze 2015, 76, 350–359. [Google Scholar]

- Haghighi, M.; Da Silva, J.T.; Mozafarian, M.; Afifipour, Z. Can Si and nano-Si alleviate the effect of drought stress induced by PEG in seed germination and seedling growth of tomato. Minerva Biotecnol. 2013, 25, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, T.M.; Imran, M.; Atta, B.M.; Ashraf, M.Y.; Hameed, A.; Waqar, I.; Shafiq, M.; Hussain, K.; Naveed, M.; Aslam, M.; Maqbool, M.A. Selection and screening of drought tolerant high yielding chickpea genotypes based on physio-biochemical indices and multi-environmental yield trials. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Yang, M.; Miao, M. Influence of SiO₂, Al₂O₃ and TiO₂ nanoparticles on okra seed germination under PEG-6000 simulated water deficit stress. J. Seed Sci. 2023, 45, e202345029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, S.; Farooq, S.; Kiani, M.Z.; Zia, M. Surface modified ZnO NPs by betaine and proline build up tomato plants against drought stress and increase fruit nutritional quality. Chemosphere 2024, 362, 142671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, N.; Ilyas, N.; Mashwani, Z.-u.-R.; Hayat, R.; Yasmin, H.; Nouredeen, A.; Ahmad, P. Synergistic effects of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria and silicon dioxide nanoparticles for amelioration of drought stress in wheat. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 166, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behboudi, F.; Tahmasebi Sarvestani, Z.; Kassaee, M.Z.; Modares Sanavi, S.A.M.; Sorooshzadeh, A. Improving growth and yield of wheat under drought stress via application of SiO₂ nanoparticles. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2018, 20, 1479–1492. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Webster, S.; He, S.Y. Growth–defense trade-offs in plants. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, R634–R639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Naggar, H.M.; Osman, A.R. Enhancing growth and bioactive metabolites characteristics in Mentha pulegium L. via silicon nanoparticles during in vitro drought stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Song, F.; Guo, J.; Zhu, X.; Liu, S.; Liu, F.; Li, X. Nano-ZnO-induced drought tolerance is associated with melatonin synthesis and metabolism in maize. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Elzaher, M.A.; El-Desoky, M.A.; Khalil, F.A.; Eissa, M.A.; Amin, A.E.-E.A. Exogenously applied proline with silicon and zinc nanoparticles to mitigate salt stress in wheat plants grown on saline soil. J. Plant Nutr. 2025, 48, 1559–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, A.A.C.; de Souza, A.L.G.; Souza, D.S.; Batista, R.A.; Xavier, A.C.R.; Pagani, G.D. Quantification of bioactive compounds of pink pepper (Schinus terebinthifolius, Raddi). Int. J. Eng. Innov. Technol. 2014, 4, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Selwey, W.A.; Alsadon, A.A.; Alenazi, M.M.; Tarroum, M.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Ahmad, A.; Osman, M.; Seleiman, M.F. Morphological and biochemical response of potatoes to exogenous application of ZnO and SiO₂ nanoparticles in a water deficit environment. Horticulturae 9, 883. [CrossRef]

- Rakhman, S.A.; Utaipan, T.; Pakhathirathien, C.; Khummueng, W. Metal and metal oxide nanoparticles from Mimusops elengi Linn. extract: Green synthesis, antioxidant activity, and cytotoxicity. Sains Malays. 2022, 51, 2857–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, K.; Ghasemi, Y.; Ebrahimzadeh, M.A. Antioxidant activity, phenol and flavonoid contents of 13 citrus species peels and tissues. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 22, 277–281. [Google Scholar]

- Basavaraj, P.S.; Rane, J.; Jangid, K.K.; Babar, R.; Kumar, M.; Gangurde, A.; Shinde, S.; Boraiah, K.M.; Harisha, C.B.; Halli, H.M.; Reddy, K.S.; Prabhakar, M. Index-based selection of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) genotypes for enhanced drought tolerance. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjan, A.; Sinha, R.; Singla-Pareek, S.L.; Pareek, A.; Singh, A.K. Shaping the root system architecture in plants for adaptation to drought stress. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Chaparro, E.H.; Ramírez-Estrada, C.A.; Anchondo-Páez, J.C.; Sánchez, E.; Pérez-Álvarez, S.; Castruita-Esparza, L.U.; Muñoz-Márquez, E.; Chávez-Mendoza, C.; Patiño-Cruz, J.J.; Franco-Lagos, C.L. Nanopriming with zinc–molybdenum in jalapeño pepper on imbibition, germination, and early growth. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, P.; Kumar, S.; Sakure, A.A.; Rafaliya, R.; Patil, G.B. Zinc oxide nanopriming elevates wheat drought tolerance by inducing stress-responsive genes and physio-biochemical changes. Curr. Plant Biol. 2023, 35, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Isla, F.; Benites-Alfaro, O.E.; Pompelli, M.F. GerminaR: An R package for germination analysis with the interactive web application “GerminaQuant for R”. Ecol. Res. 2019, 34, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Seed Testing Association (ISTA). International Rules for Seed Testing 2020; ISTA: Bassersdorf, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul-Baki, A.A.; Anderson, J.D. Vigor determination in soybean seed by multiple criteria. Crop Sci. 1973, 13, 630–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizondo-Cabalceta, E.; Monge-Pérez, J.E. Caracterización morfológica de 15 genotipos de pimiento (Capsicum annuum L.) cultivados bajo invernadero en Costa Rica. InterSedes 2017, 18, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellburn, A.R. The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. J. Plant Physiol. 1994, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irigoyen, J.J.; Einerich, D.W.; Sánchez-Díaz, M. Water stress induced changes in concentrations of proline and total soluble sugars in nodulated alfalfa (Medicago sativa) plants. Physiol. Plant. 1992, 84, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornelas-Paz, J.; Martínez-Burrola, J.M.; Ruiz-Cruz, S.; Santana-Rodríguez, V.; Ibarra-Junquera, V.; Olivas, G.I.; Pérez-Martínez, J.D. Effect of cooking on the capsaicinoids and phenolics contents of Mexican peppers. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 1619–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT® 15.2 User’s Guide; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Under 15% water stress, MT215 (Mixteco + ZnO) improved germination dynamics by reducing the average germination time by 26% and increasing the germination rate by 34% compared to IMT115. Several treatments, such as MT115, IT315, and IT415, maintained 100% germination even under water stress. Drought Stress | Treatment | Variety | Code | Germinated seeds (n) | Germinability (%) | Mean germinationtime (days) | Mean germination rate (days-1) | Germination speed (%) | Uncertainty Index (bit) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% |

T1 Hydropriming |

MT10 | 7.00 ± 0.00bc | 87.50 ± 0.00bc | 3.334 ± 0.08bcde | 0.300 ± 0.007cde | 30.0 ± 0.7cde | 1.43 ± 0.04a | MT10 |

| IT10 | 6.00 ± 0.00d | 75.00 ± 0.00d | 3.444 ± 0.10bcd | 0.291 ± 0.008de | 29.0 ± 0.8de | 0.97 ± 0.05ab | IT10 | ||

| IMT10 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 3.458 ± 0.07bcd | 0.289 ± 0.006de | 28.9 ± 0.6de | 0.98 ± 0.03ab | IMT10 | ||

| FT10 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 3.458 ± 0.07bcd | 0.289 ± 0.006de | 28.9 ± 0.6de | 0.98 ± 0.03ab | FT10 | ||

| T2 ZnO + Q |

MT20 | 7.00 ± 0.00bc | 87.50 ± 0.00bc | 3.191 ± 0.08cde | 0.313 ± 0.008bcd | 31.4 ± 0.8bc | 1.40 ± 0.04a | MT20 | |

| IT20 | 7.00 ± 0.00bc | 87.50 ± 0.00bc | 3.334 ± 0.08bcde | 0.300 ± 0.007cde | 30.0 ± 0.7bde | 0.90 ± 0.07ab | IT20 | ||

| IMT20 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 3.583 ± 0.26bc | 0.280 ± 0.020def | 28.0 ± 2.0def | 1.12 ± 0.25ab | IMT20 | ||

| FT20 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 3.458 ± 0.26bcd | 0.290 ± 0.021de | 29.0 ± 2.1de | 0.86 ± 0.08b | FT20 | ||

| T3 SiO2 + Q |

MT30 | 7.00 ± 0.00bc | 87.50 ± 0.00bc | 2.905 ± 0.08e | 0.344 ± 0.010b | 34.4 ± 1.0b | 0.78 ± 0.32b | MT30 | |

| IT30 | 7.00 ± 0.00bc | 87.50 ± 0.00bc | 2.334 ± 0.08f | 0.429 ± 0.015a | 42.9 ± 1.5a | 0.90 ± 0.07ab | IT30 | ||

| IMT30 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 3.292 ± 0.07bcde | 0.304 ± 0.007cde | 30.4 ± 0.7cde | 0.86 ± 0.08b | IMT30 | ||

| FT30 | 7.66 ± 0.57ab | 95.83 ± 7.21ab | 4.137 ± 0.14a | 0.242 ± 0.009g | 24.2 ± 0.8f | 1.42 ± 0.10a | FT30 | ||

| T4 ZnO + SiO2 + Q |

MT40 | 7.66 ± 0.57ab | 95.83 ± 7.21ab | 3.000 ± 0.13de | 0.334 ± 0.014bc | 33.4 ± 1.4bc | 1.00 ± 0.40ab | MT40 | |

| IT40 | 7.00 ± 0.00bc | 87.50 ± 0.00bc | 3.334 ± 0.08bcde | 0.300 ± 0.007cde | 30.0 ± 0.7cde | 0.90 ± 0.07ab | IT40 | ||

| IMT40 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 3.708 ± 0.26ab | 0.271 ± 0.019efg | 27.1 ± 1.8ef | 1.27 ± 0.23ab | IMT40 | ||

| FT40 | 6.33 ± 0.57cd | 83.33 ± 7.21cd | 4.095 ± 0.17a | 0.244 ± 0.010fg | 24.4 ± 1.0f | 1.42 ± 0.15a | FT40 | ||

| 15% | T1 Hydropriming |

MT115 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 2.917 ± 0.07fg | 0.343 ± 0.009a | 34.3 ± 0.8a | 0.72 ± 0.30ab | MT115 |

| IT115 | 7.33 ± 0.57abc | 91.66 ± 7.21abc | 3.696 ± 0.28abc | 0.271 ± 0.021de | 27.2 ± 2.1de | 1.20 ± 0.16ab | IT115 | ||

| IMT115 | 7.00 ± 0.00bc | 87.50 ± 0.00bc | 3.952 ± 0.41a | 0.255 ± 0.025e | 25.5 ± 2.5e | 1.25 ± 0.34ab | IMT115 | ||

| FT115 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 3.375 ± 0.13 bcdefg | 0.297 ± 0.011bcd | 29.7 ± 1.1bcd | 1.02 ± 0.25ab | FT115 | ||

| T2 ZnO + Q |

MT215 | 7.00 ± 0.00bc | 87.50 ± 0.00bc | 2.905 ± 0.08g | 0.344 ± 0.010a | 34.4 ± 1.0a | 0.78 ± 0.32ab | MT215 | |

| IT215 | 7.66 ± 0.57ab | 95.83 ± 7.21ab | 3.476 ± 0.04abcde | 0.288 ± 0.003cde | 28.8 ± 0.3cde | 1.09 ± 0.18ab | IT215 | ||

| IMT215 | 7.00 ± 0.00bc | 87.50 ± 0.00bc | 3.334 ± 0.08 bcdefg | 0.300 ± 0.007bcd | 30.0 ± 0.7bcd | 0.90 ± 0.07ab | IMT215 | ||

| FT215 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 3.375 ± 0.08 bcdefg | 0.297 ± 0.007bcd | 29.7 ± 0.7bcd | 0.92 ± 0.07ab | FT215 | ||

| T3 SiO2 + Q |

MT315 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 3.042 ± 0.07 efg | 0.329 ± 0.008ab | 32.9 ± 0.8ab | 0.54 ± 0.53ab | MT315 | |

| IT315 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 3.208 ± 0.07cdefg | 0.312 ± 0.007abc | 31.2 ± 0.7abc | 0.72 ± 0.15b | IT315 | ||

| IMT315 | 6.66 ± 0.57cd | 83.33 ± 7.21cd | 3.595 ± 0.11abcd | 0.278 ± 0.009cde | 27.8 ± 0.8cde | 1.36 ± 0.10a | IMT315 | ||

| FT315 | 7.00 ± 0.00bc | 87.50 ± 0.00bc | 3.429 ± 0.14 bcdef | 0.292 ± 0.012bcde | 29.2 ± 1.2bcde | 0.94 ± 0.07ab | FT315 | ||

| T4 ZnO + SiO2 + Q |

MT415 | 6.00 ± 0.00d | 75.00 ± 0.00d | 3.167 ± 0.17defg | 0.316 ± 0.017abc | 31.6 ± 1.7abc | 0.52 ± 0.47fb | MT415 | |

| IT415 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 3.417 ± 0.07 bcdefg | 0.293 ± 0.006bcde | 29.3 ± 0.6bcde | 0.97 ± 0.03ab | IT415 | ||

| IMT415 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 3.792 ± 0.14ab | 0.264 ± 0.010de | 26.4 ± 1.0de | 1.46 ± 0.09a | IMT415 | ||

| FT415 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 3.458 ± 0.14 abcde | 0.289 ± 0.012efg | 28.9 ± 1.2bcde | 1.14 ± 0.24abcde | FT415 | ||

| 30% | T1 Hydropriming |

MT130 | 7.66 ± 0.57ab | 95.83 ± 7.21ab | 3.268 ± 0.15d | 0.307 ± 0.014a | 30.6 ± 1.4a | 1.03 ± 0.25bcd | MT130 |

| IT130 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 3.375 ± 0.13 cd | 0.297 ± 0.011abc | 29.7 ± 1.1abc | 0.92 ± 0.10d | IT130 | ||

| IMT130 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 4.292 ± 0.19ab | 0.233 ± 0.010e | 23.3 ± 1.0e | 1.82 ± 0.23a | IMT130 | ||

| FT130 | 7.00 ± 0.00ab | 87.50 ± 0.00ab | 4.095 ± 0.08abc | 0.244 ± 0.005de | 24.4 ± 0.5de | 1.36 ± 0.20abcd | FT130 | ||

| T2 ZnO + Q |

MT230 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 3.708 ± 0.07 abcd | 0.270 ± 0.005abcde | 27.0 ± 0.5abcde | 1.44 ± 0.05abcd | MT230 | |

| IT230 | 6.33 ± 1.52b | 79.16 ± 19.04b | 3.992 ± 0.46 abcd | 0.253 ± 0.028cde | 25.3 ± 2.8cde | 1.17 ± 0.18bcd | IT230 | ||

| IMT230 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 4.000 ± 0.33abcd | 0.251 ± 0.020cde | 25.1 ± 2.0cde | 1.45 ± 0.14abc | IMT230 | ||

| FT230 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 3.292 ± 0.07d | 0.304 ± 0.007ab | 30.4 ± 0.7ab | 0.86 ± 0.08d | FT230 | ||

| T3 SiO2 + Q |

MT330 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 3.625 ± 0.13 bcd | 0.276 ± 0.010abcde | 27.6 ± 1.0abcde | 1.12 ± 0.25bcd | MT330 | |

| IT330 | 7.33 ± 0.57ab | 91.66 ± 7.21ab | 3.690 ± 0.27 abcd | 0.272 ± 0.019abcde | 27.2 ± 1.9abcde | 1.22 ± 0.21bcd | IT330 | ||

| IMT330 | 7.00 ± 0.00ab | 87.50 ± 0.00ab | 3.857 ± 0.38 abcd | 0.261 ± 0.025abcde | 26.1 ± 2.4abcde | 1.56 ± 0.25abc | IMT330 | ||

| FT330 | 7.33 ± 0.57ab | 91.66 ± 7.21ab | 3.958 ± 0.29 abcd | 0.253 ± 0.018bcde | 25.4 ± 1.8bcde | 1.62 ± 0.20ab | FT330 | ||

| T4 ZnO + SiO2 + Q |

MT430 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 3.417 ± 0.07 cd | 0.293 ± 0.006abcd | 29.3 ± 0.6abcd | 0.97 ± 0.03cd | MT430 | |

| IT430 | 8.00 ± 0.00a | 100.00 ± 0.00a | 3.500 ± 0.25 cd | 0.287 ± 0.021abcd | 28.7 ± 2.1abcd | 1.27 ± 0.23abcd | IT430 | ||

| IMT430 | 6.33 ± 0.57b | 79.16 ± 7.21b | 4.436 ± 0.36a | 0.226 ± 0.017e | 22.6 ± 1.8e | 1.18 ± 0.24bcd | IMT430 | ||

| FT430 | 6.33 ± 0.57b | 79.16 ± 7.21b | 3.690 ± 0.13 abcd | 0.271 ± 0.010abcde | 27.1 ± 1.0abcde | 1.43 ± 0.05abcd | FT430 |

| Jalapeño pepper varieties |

Treatment NPs + Chitosan |

Code |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of osmotic stress | ||||

| 0% | 15% | 30% | ||

|

Mixteco (M) |

(T1) Triple-distilled water Control | MT10 | MT115 | MT130 |

| (T2) ZnO 100 mgL-1 + Q 100 mgL-1 | MT20 | MT215 | MT230 | |

| (T3) SiO2 10 mgL-1 + Q 100 mgL-1 | MT30 | MT315 | MT330 | |

| (T4) ZnO 100 mgL-1 + SiO2 10 mgL-1 + Q 100 mgL-1 | MT40 | MT415 | MT430 | |

|

Ideal (I) |

(T1) Triple-distilled water Control | IT10 | IT115 | IT130 |

| (T2) ZnO 100 mgL-1 + Q 100 mgL-1 | IT20 | IT215 | IT230 | |

| (T3) SiO2 10 mgL-1 + Q 100 mgL-1 | IT30 | IT315 | IT330 | |

| (T4) ZnO 100 mgL-1 + SiO2 10 mgL-1 + Q 100 mgL-1 | IT40 | IT415 | IT430 | |

|

Imperial (IM) |

(T1) Triple-distilled water Control | IMT10 | IMT115 | IMT130 |

| (T2) ZnO 100 mgL-1 + Q 100 mgL-1 | IMT20 | IMT215 | IMT230 | |

| (T3) SiO2 10 mgL-1 + Q 100 mgL-1 | IMT30 | IMT315 | IMT330 | |

| (T4) ZnO 100 mgL-1 + SiO2 10 mgL-1 + Q 100 mgL-1 | IMT40 | IMT415 | IMT430 | |

|

Forajido (F) |

(T1) Triple-distilled water Control | FT10 | FT115 | FT130 |

| (T2) ZnO 100 mgL-1 + Q 100 mgL-1 | FT20 | FT215 | FT230 | |

| (T3) SiO2 10 mgL-1 + Q 100 mgL-1 | FT30 | FT315 | FT330 | |

| (T4) ZnO 100 mgL-1 + SiO2 10 mgL-1 + Q 100 mgL-1 | FT40 | FT415 | FT430 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).