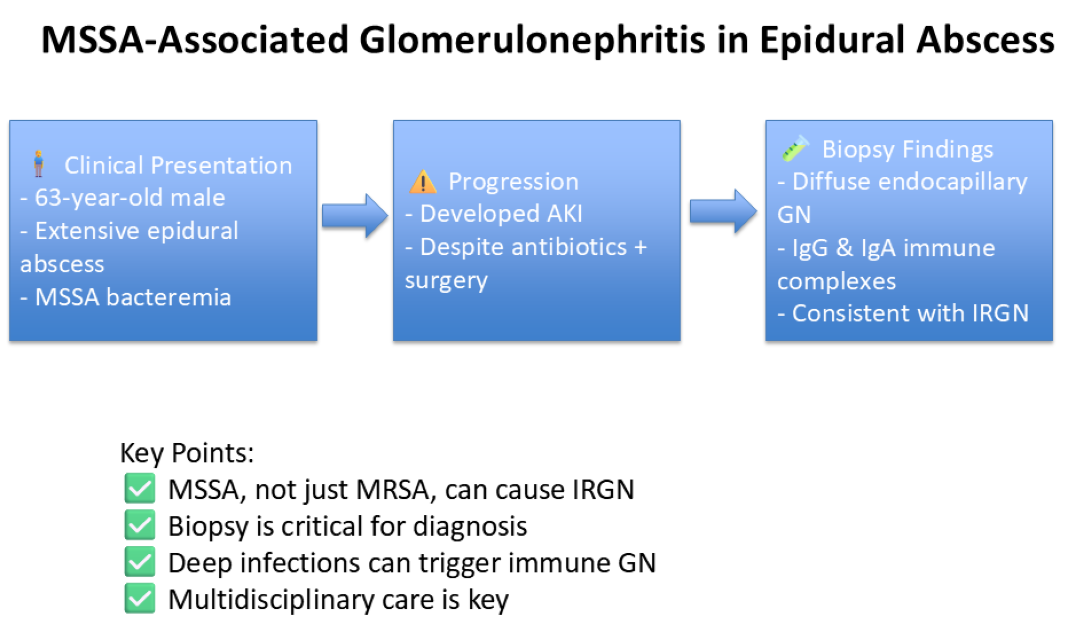

Introduction

Infection-related glomerulonephritis (IRGN) is an immune-mediated condition affecting the kidneys, triggered by nonrenal bacterial infections [

1]. It has various types, including post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN), IgA-dominant (Staphylococcus-associated) infection-related GN, endocarditis-associated GN, and shunt nephritis [

2]. PSGN had historically been the most common IRGN; however, in the last 2 decades, there has been a shift regarding the underlying cause, with pathogens shifting to staphylococcal infections, as well as some viruses associated with IRGN [

2,

3]. The types of pathogens and infection sites have also changed, with staphylococcal infections as prevalent as streptococcal ones in adults, and three times more common in the elderly [

2].

Staphylococcus infection-associated glomerulonephritis (SAGN), although initially only reported with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), with increasing incidence in recent years, is also reported in methicillin-sensitive strains [

4].

Pathogenesis results from immune complex deposition in the glomeruli, where these complexes are usually formed by immunoglobulin (Ig)G antibodies and bacterial antigens. The glomerular damage often shows mild-to-moderate IgA and strong complement factor 3 (C3) staining. However, IgA is not always the predominant feature, indicating variability in the immunological response [

5].

In this paper, we report the presentation of a 63-year-old male patient with acute kidney injury (AKI) in the setting of IGRN secondary to MSSA bacteremia.

Case Discussion

A 63-year-old male with a medical history of umbilical hernia, occipital headache, gout, hyperlipidemia, marijuana use, and potential alcohol abuse presented to the emergency department complaining of low back pain. The evaluation revealed a large ventral epidural abscess extending from C2 to L4, necessitating admission to the surgical service for laminectomy and drainage. Initial antibiotic therapy with Vancomycin was initiated, later adjusted to target methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) initially with cefalexin, then switched to nafcillin.

The patient had a complicated hospital course resulting in admission to a higher level for sepsis and underwent surgery, hemilaminectomy at C2 and laminectomies at C3, L3-L5 with abscess evacuation.

Despite surgical drainage, the patient continued to spike fevers. Transthoracic echocardiography identified mobile 7mm vegetations on the noncoronary cusps of the aortic valve, with subsequent negative findings on transesophageal ultrasound. Prolonged antibiotic therapy was initiated for at least 6 weeks.

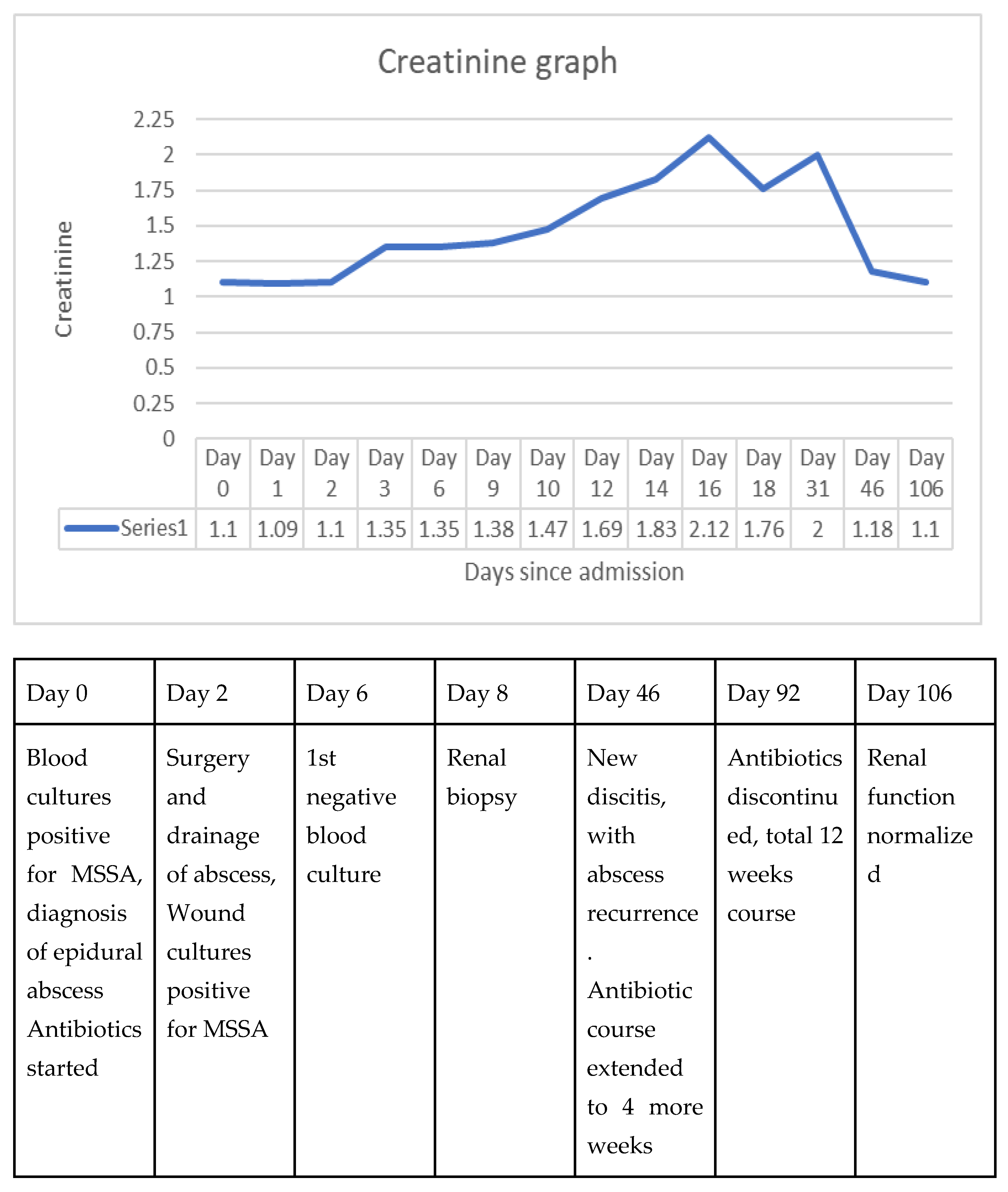

The hospital course was further complicated by a skin rash attributed to nafcillin, prompting a switch to cefalexin. Additional complications included shortness of breath with lung infiltrates in the right lower lung field, treated as pneumonia with levofloxacin. Worsening lower extremity edema, hypertension, and rising creatinine levels prompted a nephrology consultation for an acute kidney injury (AKI) workup. Urinalysis revealed hematuria, proteinuria, and an elevated protein-creatinine ratio, with negative results on hepatitis and immunological workup, as seen in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

Blood work and urine analysis:

Acute Kidney Injury Workup:

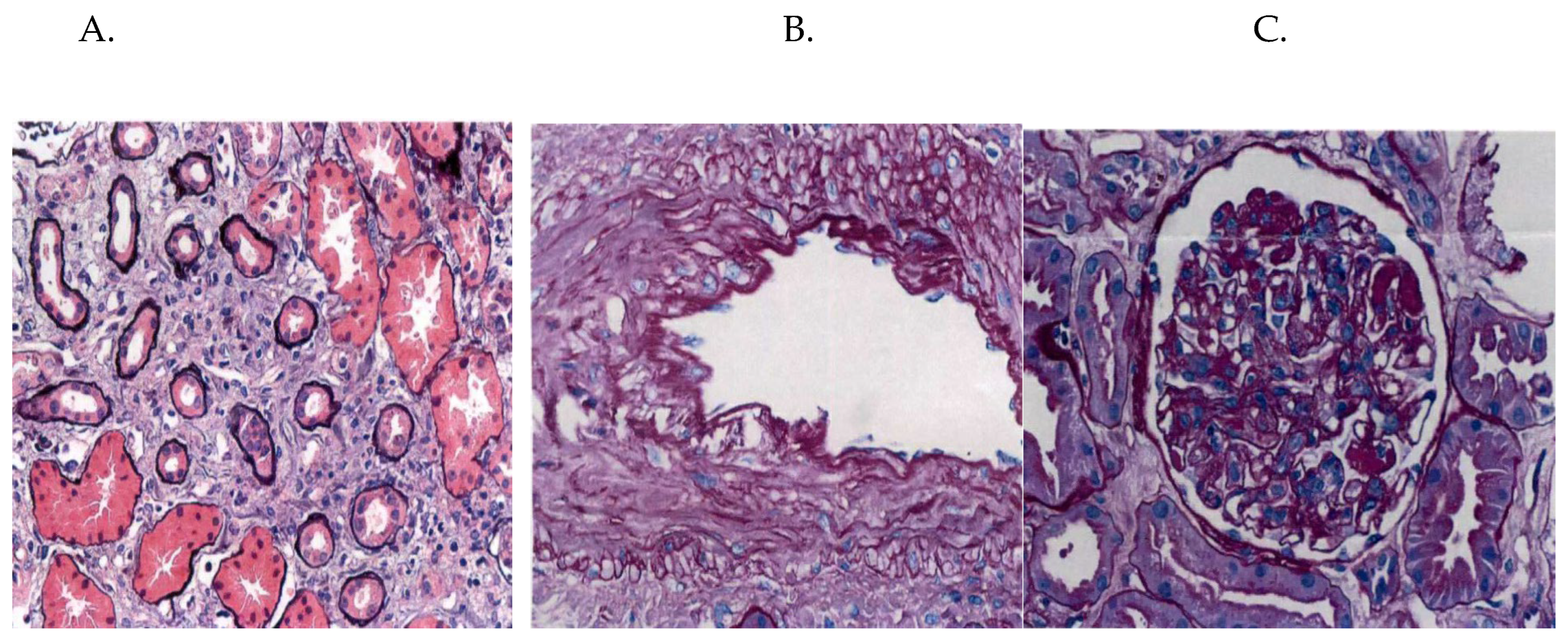

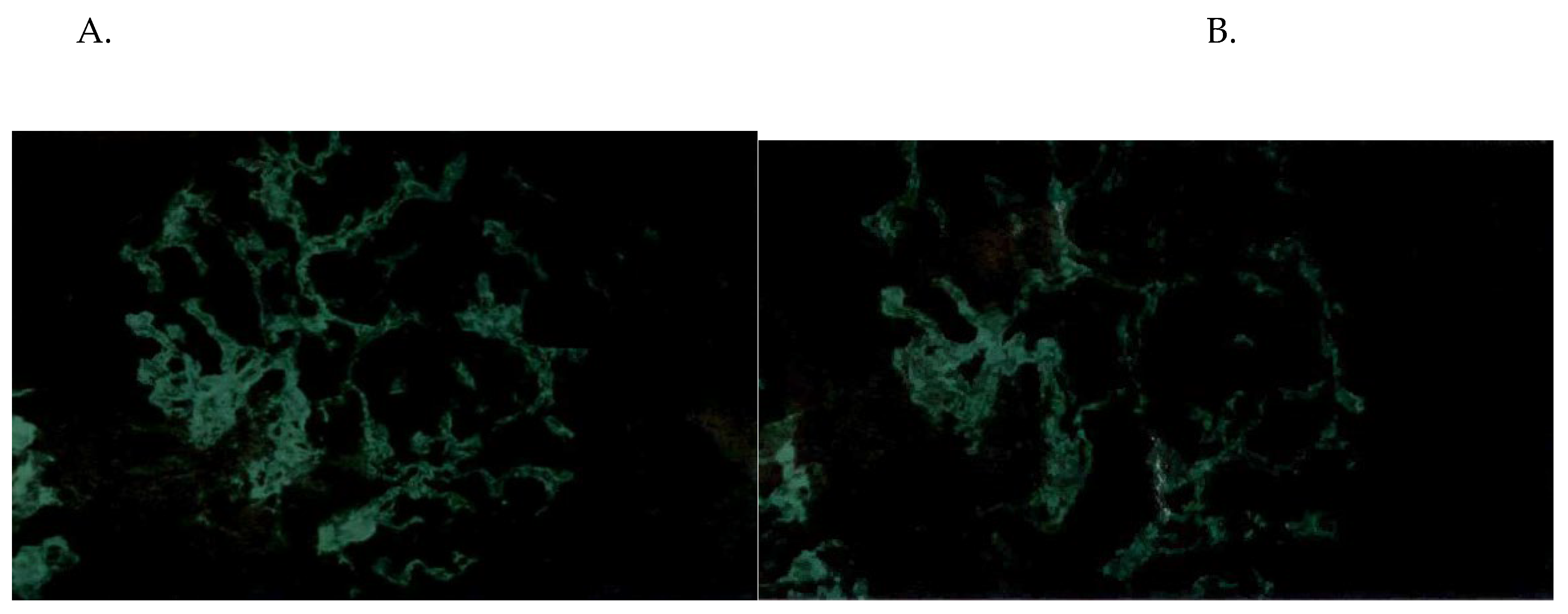

Due to persistent skin rash and worsening renal function, concerns for acute interstitial nephritis or infection-related glomerulonephritis arose, leading to a kidney biopsy. Biopsy findings indicated diffuse endocapillary proliferative glomerulonephritis with immune thrombi and polytypic IgG and IgA-dominant deposits, alongside mild acute tubular injury, moderate arteriosclerosis, and mild arteriolosclerosis. Cryoglobulin levels were negative. Immunosuppressive therapy was deferred due to the absence of crescentic disease and ongoing infection risk.

Figure 1.

A. Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy, B. Intimal Fibrosis, C. Hypercellular glomeruli with immune thrombi.

Figure 1.

A. Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy, B. Intimal Fibrosis, C. Hypercellular glomeruli with immune thrombi.

Figure 2.

A. IgG deposits, B. IgA deposits.

Figure 2.

A. IgG deposits, B. IgA deposits.

Creatinine graph

Figure 3.

Creatinine course, with a timeline of important clinical courses.

Figure 3.

Creatinine course, with a timeline of important clinical courses.

Following stabilization of renal function, the patient was discharged and has since been followed up by nephrology and infectious disease outpatient clinics. He completed a 12-week course of cefalexin, with weekly chemistries showing improving creatinine levels, and normal kidney function in 3 months.

POST DISCHARGE BLOODWORK.

Discussion

Over the last 2 decades, with the decline in PSGN, there has been a surge in SAGN associated with an increase in Staphylococcus aureus infection with resistant strains including MRSA. SAGN, although uncommon, has had an increased incidence, more so in middle-aged or older adults [

2,

3,

4].

The pathogenesis of SAGN, similar to PSGN, results from immune complex deposition in the glomeruli. Immune complexes formed from immunoglobulin (Ig)G antibodies and bacterial antigens are deposited in the glomerulus, causing complement activation and further activation of immune cells, resulting in glomerular damage [

5,

6,

7].

However, a fundamental difference in the pathogenesis remains the timing of the development of GN. PSGN classically occurs 2-3 weeks after infection resolution, while SAGN has been predominantly found to occur with ongoing infections. It is common with endocarditis but is also seen in skin abscesses, osteomyelitis, and indwelling shunts. In this case report, the patient also developed SAGN with AKI while being treated for the infection, although with a prolonged course of antibiotics due to the extensive nature of the infection [

8,

9].

SAGN results from immune complex deposition in the glomeruli, with complexes containing IgG antibodies, but instances of IgA deposition have also been seen. In cases linked to MRSA, MSSA, or even Staphylococcus epidermidis, the glomerular damage often shows mild-to-moderate IgA and strong complement factor 3 (C3) staining. However, IgA is not always the predominant feature, indicating variability in the immunological response [

5,

10] [

4]. Further, SAGN has been more frequently associated with endocarditis or indwelling shunts, with considerations of more immune mechanisms that could be contributing further to the SAGN [

8,

9]. This index case similarly presents with biopsy-proven IgG and IgA deposition in the glomerulus, causing SAGN, occurring with less reported MSSA infection, even more so in the absence of endocarditis.

Although the host genetic factors contributing to SAGN are not yet fully understood, the IgA-dominant form of post-infectious glomerulonephritis seen in SAGN suggests that individuals with a predisposition toward IgA nephropathy may be more susceptible. This could involve polymorphisms in genes regulating IgA production and deposition, such as the MUC1 gene, which has been implicated in other forms of IgA nephropathy [

11]. Host genetic variants in cytokine production (such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10), T-cell receptor signaling, and complement system regulation might modulate the immune response to

S. aureus, influencing the severity and likelihood of GN. Variations in genes like CFH (complement factor H) may also be involved in differential susceptibility to SAGN [

5].

Similar to the index case, with the complicated nature of the presentation of these infections with either endocarditis or large abscesses which could be complicated by bacteremia, sepsis, or shock, there can be other explanations for the AKI, including acute tubular necrosis (ATN) and hypotension or microthrombi causing acute interstitial nephritis (ATN) which can make a diagnosis tricky. Kidney biopsy as such becomes fundamental for the diagnosis of the cause as well as understanding of the immunological aspect of the disease.

Similarly in this case, as revealed by the biopsy findings of tubulointerstitial inflammation and tubular atrophy alongside glomerular involvement, AKI could be multifactorial with both IGRN and AIN resulting in his presentation. Though AIN is usually drug-induced, it can also be triggered by infections. The positive staining for nephritis-associated plasmin receptor (NAPlr) in the tubulointerstitial infiltrates supports the diagnosis of infection-related AIN, a rare but recognized complication of bacterial infections. This is consistent with previous reports showing that NAPlr is a useful marker for distinguishing SAGN from other forms of glomerulonephritis, particularly in the presence of AIN [

12]. Several case reports have documented instances of NAPlr with IRAIN (infection-related acute interstitial nephritis), which were further complicated by infection-related glomerulonephritis (IRGN). In these cases, atypical findings such as blood eosinophilia and renal tubulointerstitial eosinophil infiltration were noted—features that are not commonly observed in typical cases of IRGN [

13,

14].

Management of IGRN included treatment of the underlying infection as well as addressing the glomerular inflammation. Treatment of infection with source control with as-needed drainage, surgery, and management with a prolonged course of appropriate antibiotics. For MRSA infections, treatment typically involves polypeptide antibiotics (such as vancomycin and teicoplanin) and aminoglycosides (like arbekacin), with dosages adjusted according to renal function and drug levels to avoid side effects. In cases of deep infections, a prolonged course of up to six weeks and surgical intervention to remove infected tissue may be necessary [

5]. In our patient, despite aggressive antibiotic therapy and surgical drainage of the abscess, kidney function continued to decline, raising concern for ongoing renal injury due to immune-mediated mechanisms. As such, additional management with corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressants was deemed necessary.

Although the patient was initially started on oral steroids, immunosuppressive therapy was ultimately deferred due to the absence of crescentic glomerulonephritis and the heightened risk of worsening the underlying infection. The patient had rapid improvement in kidney function with normalization of creatinine within 3 months with antibiotics, with the resolution of AKI.

However, in published studies, there have been conflicting reports of worsening infection as well as increasing mortality associated with steroids or immunosuppressant use [

5]. In a cohort of elderly patients treated with corticosteroids, renal lesions improved in only 14%, while 18% of the patients died from worsening infection [

15]. Another study in patients with endocarditis showed that those treated with corticosteroids had a higher mortality rate (23.5%) compared to those treated with antibiotics alone (10%) [

5,

16] .

Furthermore, a review by Takayasu et al. evaluated 62 published case reports and found that among 34 patients treated with corticosteroids for IgA-dominant infection-related glomerulonephritis (IgA-IRGN) or Staphylococcus-associated glomerulonephritis (SAGN), 12% died, 29% developed end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), and 41% achieved remission. In contrast, in 32 patients not treated with corticosteroids, 6% died, 13% developed ESKD, and 44% achieved remission [

5].

Alternative treatments, including plasma exchange to remove immune complexes and endotoxin adsorption with polymyxin-immobilized fibers, are also used infrequently and have limited published data [

17,

18].

In conclusion, this case emphasizes the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges associated with Staphylococcus-associated glomerulonephritis and infection-related AIN. Kidney biopsy remains crucial in distinguishing between various etiologies of AKI in the setting of infection. While immunosuppressive therapy may be beneficial in select cases, the management of infection-related glomerulonephritis should prioritize infection control and supportive care. The role of NAPlr staining in diagnosing AIN in such settings deserves further exploration, as it may provide a valuable tool for guiding therapeutic decisions.

Author Contributions

Sadikshya Bhandari, Case review, Literature review, Manuscript writing and editing, Tenzin Tamdin, Case review, Literature review, Manuscript writing and editing, Dinmukhammed Osser, Manuscript writing and editing, Christopher Morgan, Manuscript editing and supervision, Panupong Lisawat, Manuscript editing and supervision

Funding

No funding sources.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal consent for publication, identifiable patient information not present in the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Website. Available: DEFINE_ME. [cited 12 Sep 2024]. Available: https://www.kidney-international.org/article/S0085-2538(15)55815-8/fulltext.

- Khalighi MA, Chang A. Infection-Related Glomerulonephritis. Glomerular Diseases. 2021;1: 82.

- DEFINE_ME. [cited 12 Sep 2024]. Available: https://www.kidney-international.org/article/S0085-2538(15)55815-8/fulltext.

- Wang S-Y, Bu R, Zhang Q, Liang S, Wu J, Liu X-GZS-W, et al. Clinical, Pathological, and Prognostic Characteristics of Glomerulonephritis Related to Staphylococcal Infection. Medicine . 2016;95: e3386. [CrossRef]

- Takayasu M, Hirayama K, Shimohata H, Kobayashi M, Koyama A. Staphylococcus aureus Infection-Related Glomerulonephritis with Dominant IgA Deposition. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23. [CrossRef]

- Website. Available: https://www.kidney-international.org/action/showCitFormats?doi=10.1038%2Fki.2012.407&pii=S0085-2538%2815%2955815-8.

- Yousif Y, Okada K, Batsford S, Vogt A. Induction of glomerulonephritis in rats with staphylococcal phosphatase: new aspects in post-infectious ICGN. Kidney Int. 1996;50: 290–297. [CrossRef]

- Nadasdy T, Hebert LA. Infection-related glomerulonephritis: understanding mechanisms. Semin Nephrol. 2011;31: 369–375. [CrossRef]

- Glassock RJ, Alvarado A, Prosek J, Hebert C, Parikh S, Satoskar A, et al. Staphylococcus-related glomerulonephritis and poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis: why defining “post” is important in understanding and treating infection-related glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65: 826–832. [CrossRef]

- Satoskar AA, Nadasdy T. Bacterial Infections and the Kidney. Springer; 2017.

- Website. Available: (https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00467-012-2229-2).

- Okunaga I, Makino S-I, Honda D, Tatsumoto N, Aizawa M, Oda T, et al. IgA-dominant infection-related glomerulonephritis with NAPlr-positive tubulointerstitial nephritis. CEN Case Rep. 2023;12: 402–407. [CrossRef]

- Okabe M, Takamura T, Tajiri A, Tsuboi N, Ishikawa M, Ogura M, et al. A case of infection-related glomerulonephritis with massive eosinophilic infiltration. Clin Nephrol. 2018;90: 142–147. [CrossRef]

- Kanazawa N, Iyoda M, Hayashi J, Honda K, Oda T, Honda H. A case of acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis complicated by interstitial nephritis related to streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin B. Pathol Int. 2022;72: 200–206. [CrossRef]

- Nasr SH, Fidler ME, Valeri AM, Cornell LD, Sethi S, Zoller A, et al. Postinfectious glomerulonephritis in the elderly. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22: 187–195. [CrossRef]

- Boils CL, Nasr SH, Walker PD, Couser WG, Larsen CP. Update on endocarditis-associated glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 2015;87: 1241–1249. [CrossRef]

- Yamashita Y, Tanase T, Terada Y, Tamura H, Akiba T, Inoue H, et al. Glomerulonephritis after methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection resulting in end-stage renal failure. Intern Med. 2001;40: 424–427. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura T, Ushiyama C, Suzuki Y, Osada S, Inoue T, Shoji H, et al. Hemoperfusion with polymyxin B-immobilized fiber in septic patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-associated glomerulonephritis. Nephron Clin Pract. 2003;94: c33–9. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Blood work and urine analysis on the day of admission (Day 0).

Table 1.

Blood work and urine analysis on the day of admission (Day 0).

| Laboratory values |

Normal levels, unit |

Patient’s levels |

| |

Day 0 of Admission |

Day 12 of Admission |

| Blood chemistries |

|

|

| Creatinine |

0.6-1.23 mg/dl |

1.10 |

1.63 |

| BUN (blood urea nitrogen) |

6-23 mg/dl |

22 |

10 |

| Sodium |

135-145, mmol/L |

130 |

137 |

| Potassium |

3.5-5.3, mmol/L |

4.1 |

3.5 |

| Chloride |

97-107 mmol/L |

89 |

99 |

| Bicarbonate |

22-29 mmol/L |

24 |

26 |

| Anion Gap |

10-19 mmol/L |

17 |

12 |

| Uric acid |

3.7-8 mg/dl |

7.3 |

|

| Albumin |

3.7-5.1 g/dl |

3.5 |

|

| HbA1c |

4- 5.6 % |

5.9 |

|

| Complete blood counts |

|

|

| White blood count |

3.5-10 x10(9)/L |

26.9, neutrophilic |

11.4, neutrophilic |

| Hemoglobin |

13.5-17 g/dl |

12.5 |

7.4 |

| Platelets |

150-400 x10(9)/L |

346 |

568 |

| Urine analysis |

|

|

| pH |

4.8-8 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

| Specific gravity |

1.001-1.035 |

1.042 |

1.014 |

| Glucose |

Negative |

Negative |

Negative |

| Blood |

Negative |

Trace |

2+ |

| Protein |

Negative |

1+ |

Trace |

| Bilirubin |

Negative |

Negative |

Negative |

| Nitrites |

Negative |

Negative |

Negative |

| Leukocyte esterase |

Negative |

Negative |

Negative |

| WBC |

<5/HPF |

0-2 |

0-2 |

| RBC |

<5/HPF |

0-2 |

21-50 |

| Bacteria |

0-940/HPF |

22 |

54 |

| Casts |

|

11-20 |

3-5 |

| Protein/creatinine ratio |

<=0.11 mg/mg Cr |

|

0.32 |

| Protein, quantitative |

mg/dl |

|

40 |

| Creatinine |

mg/dl |

64 |

126 |

| Osmolality |

50-1200 mOsm/kg H2O |

370 |

|

| Sodium |

mmol/L |

<20 |

|

| Potassium |

mmol/L |

16.5 |

|

Table 2.

Workup for acute kidney injury, hepatitis, syphilis, and immunological workup.

Table 2.

Workup for acute kidney injury, hepatitis, syphilis, and immunological workup.

| Hepatitis Panel |

| Hepatitis A total Antibody (Ab) |

Non-reactive (NR) |

| Hepatitis B surface Ab |

<3.5 |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen |

NR |

| Hepatitis C Ab |

NR |

| Immunology |

| ANA Titer |

1:180, homogenous pattern |

| Centromere Ab |

<0.2, Negative |

| Chromatin Ab |

<0.2, Negative |

| Double-stranded Deoxyribonucleoside Ab |

2, Negative |

| JO-1 Ab |

<0.2, Negative |

| Ribosomal P Ab |

<0.2, Negative |

| Ribonucleoprotein |

<0.2, Negative |

| Anti-topoisomerase I (Scl-70) Ab |

<0.2, Negative |

| Smith Ab |

<0.2, Negative |

| Anti Ro (SSA) Ab |

<0.2, Negative |

| Anti La (SSB) Ab |

<0.2, Negative |

| Myeloperoxidase Ab |

<0.2, Negative |

| Proteinase 3 Ab |

<0.2, Negative |

| Immunoglobulin (Ig), Normal values in brackets |

| IgA |

783 (70-400) |

| IgG |

723 (700-1600) |

| IgM |

78 (40-230) |

| Complements, Normal values in brackets |

| C3 |

88 (75-180) |

| C4 |

21 (10-40) |

| Syphilis Ab |

NR |

| Cryoglobulin |

Negative |

Table 3.

Post-discharge, most recent bloodwork available, 6 months post-discharge.

Table 3.

Post-discharge, most recent bloodwork available, 6 months post-discharge.

| Laboratory values |

Normal levels, unit |

Patient’s levels (Most Recent) |

| Blood chemistries |

|

| Creatinine |

0.6-1.23 mg/dl |

1.07 |

| BUN (blood urea nitrogen) |

6-23 mg/dl |

20 |

| EGFR |

>=60 |

78 |

| Sodium |

135-145, mmol/L |

140 |

| Potassium |

3.5-5.3, mmol/L |

4.6 |

| Chloride |

97-107 mmol/L |

102 |

| Bicarbonate |

22-29 mmol/L |

30 |

| Complete blood counts |

|

| White blood count |

3.5-10 x10(9)/L |

10.5 |

| Hemoglobin |

13.5-17 g/dl |

7.3 |

| Platelets |

150-400 x10(9)/L |

375 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).