Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

09 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

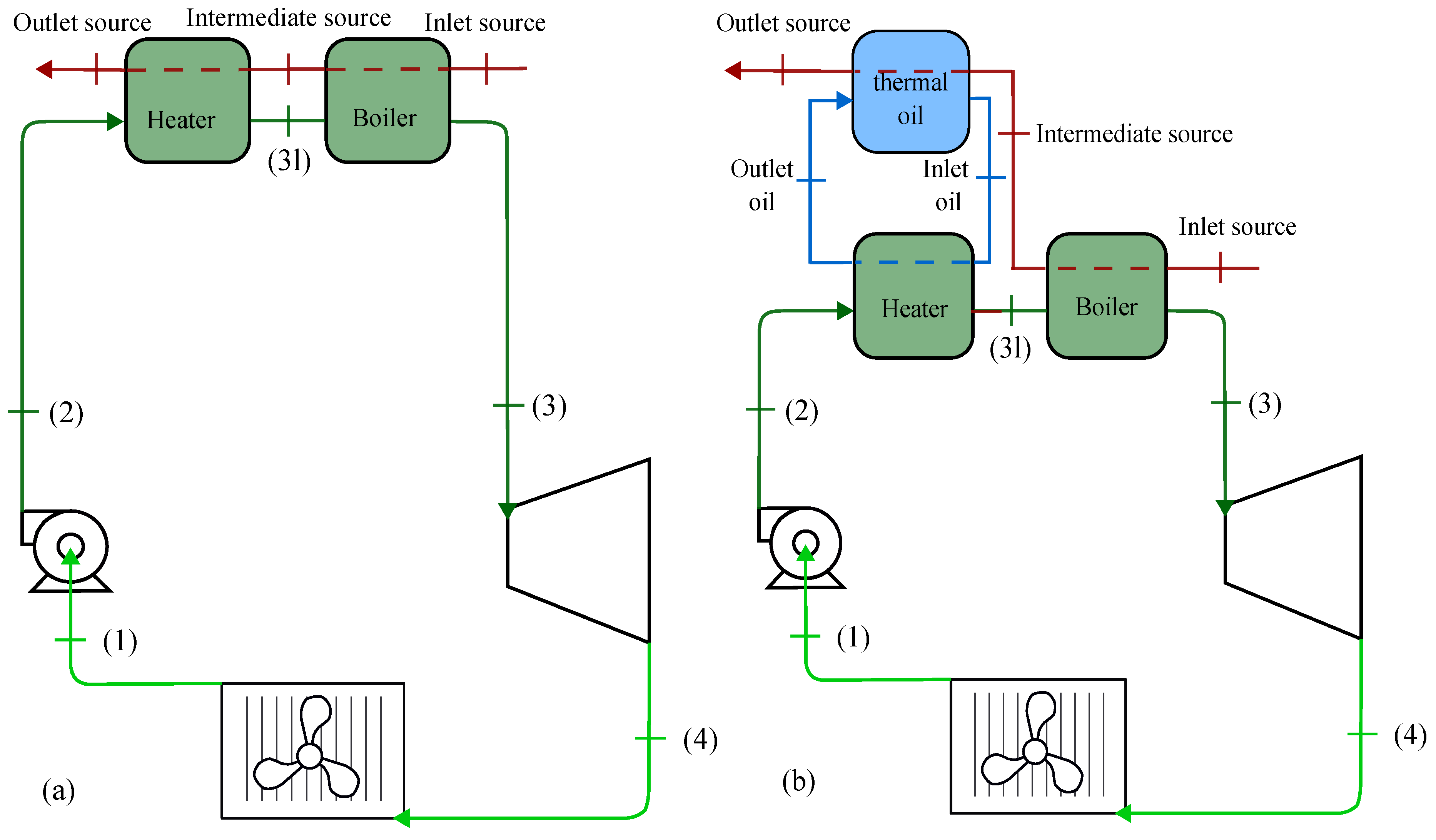

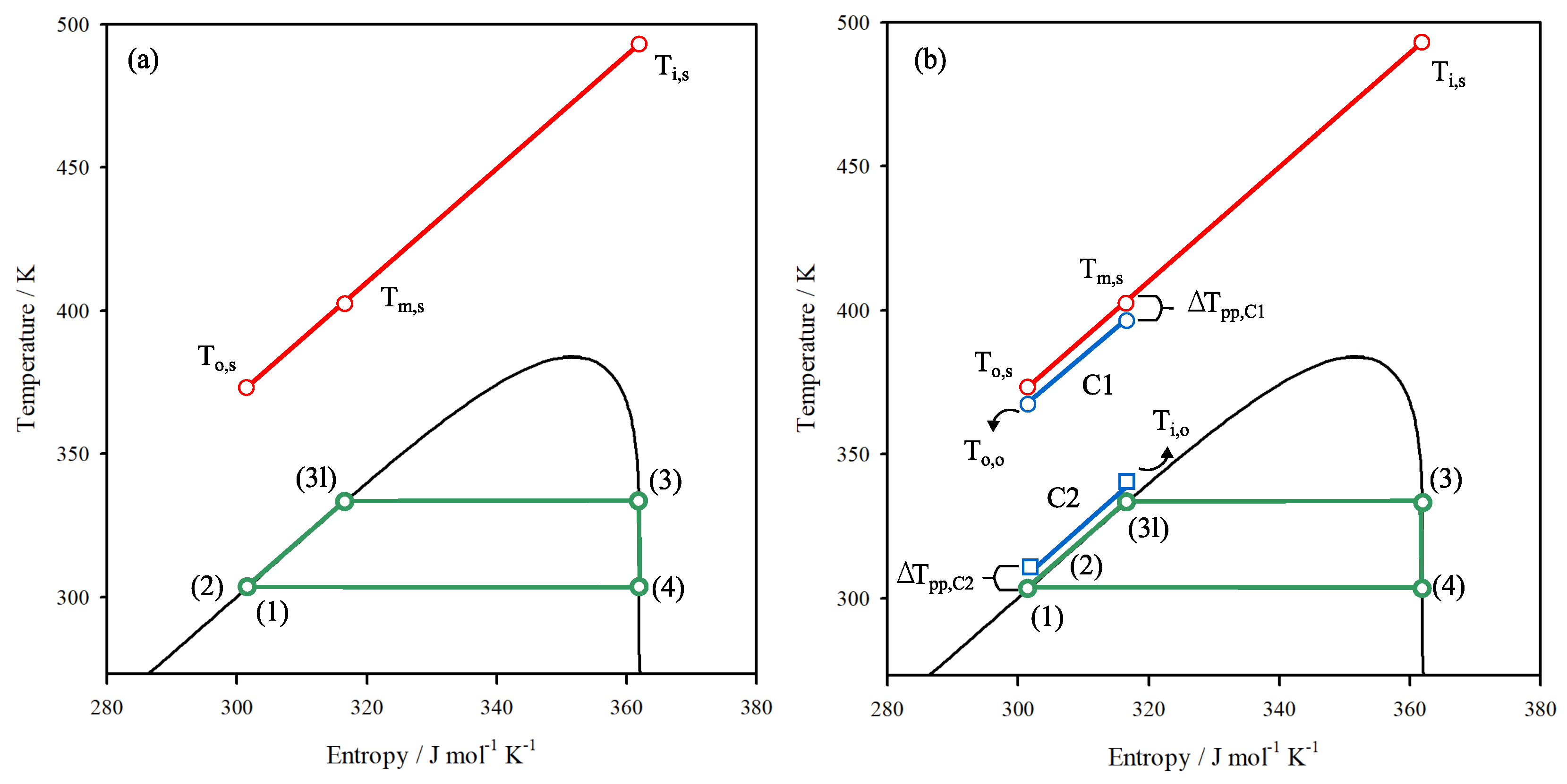

2. Thermodynamic Theory and Modelling

2.1. Thermodynamic Model

2.2. Heat Exchanger Sizing Model

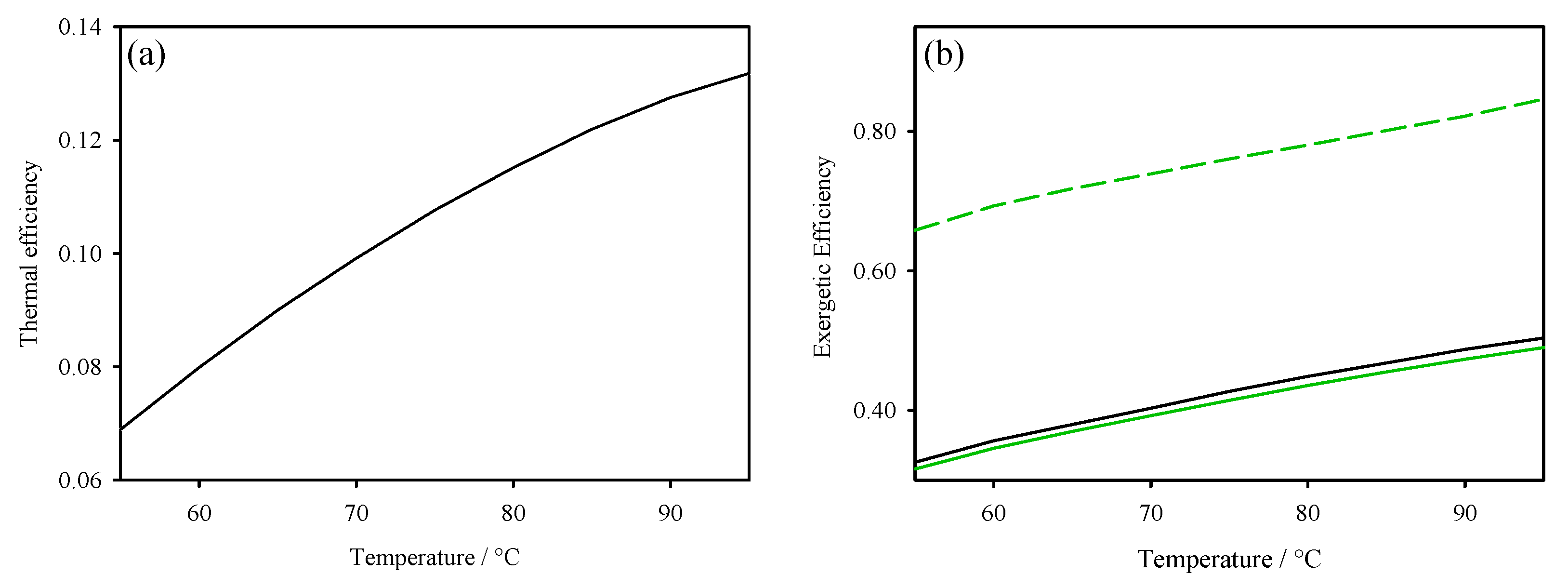

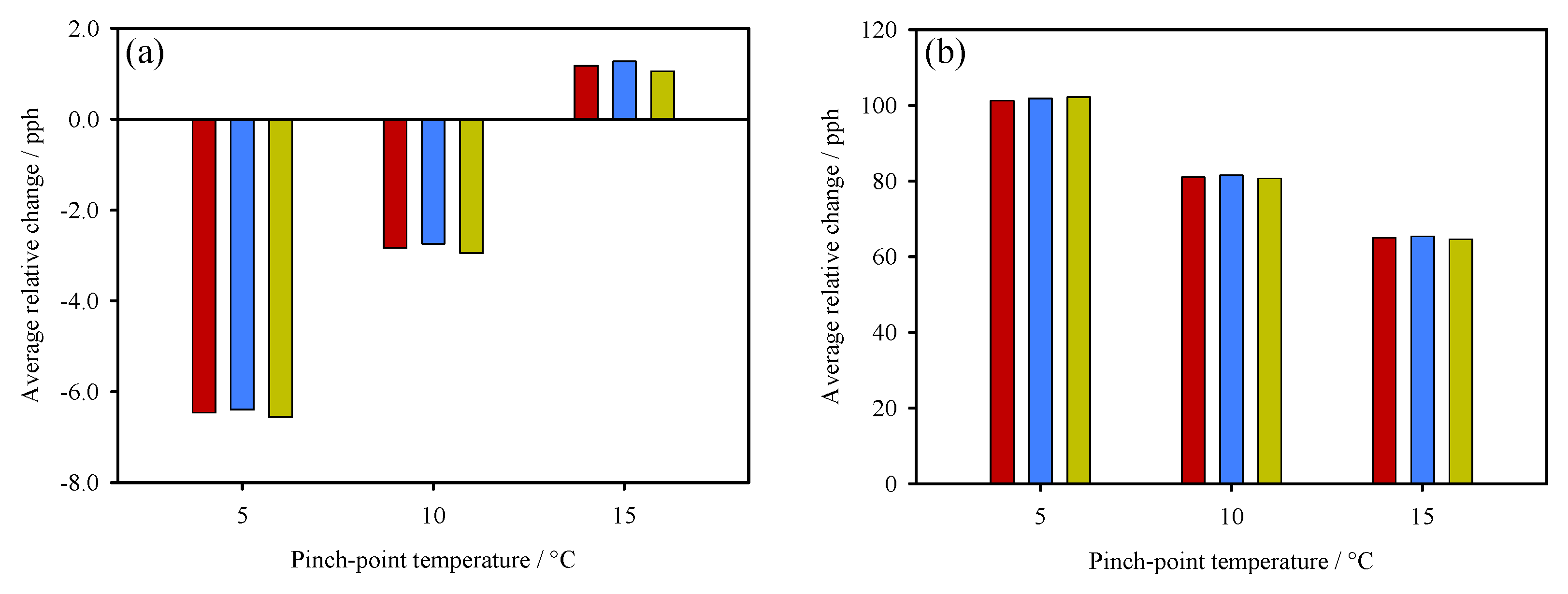

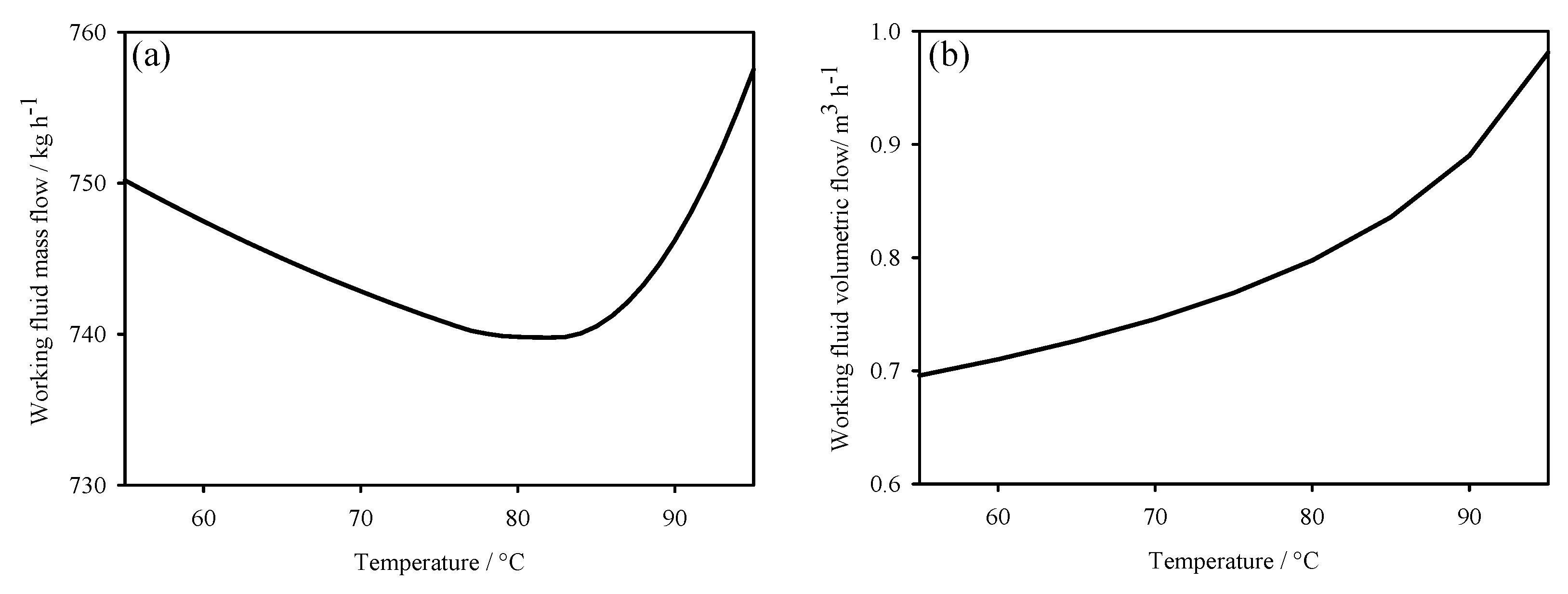

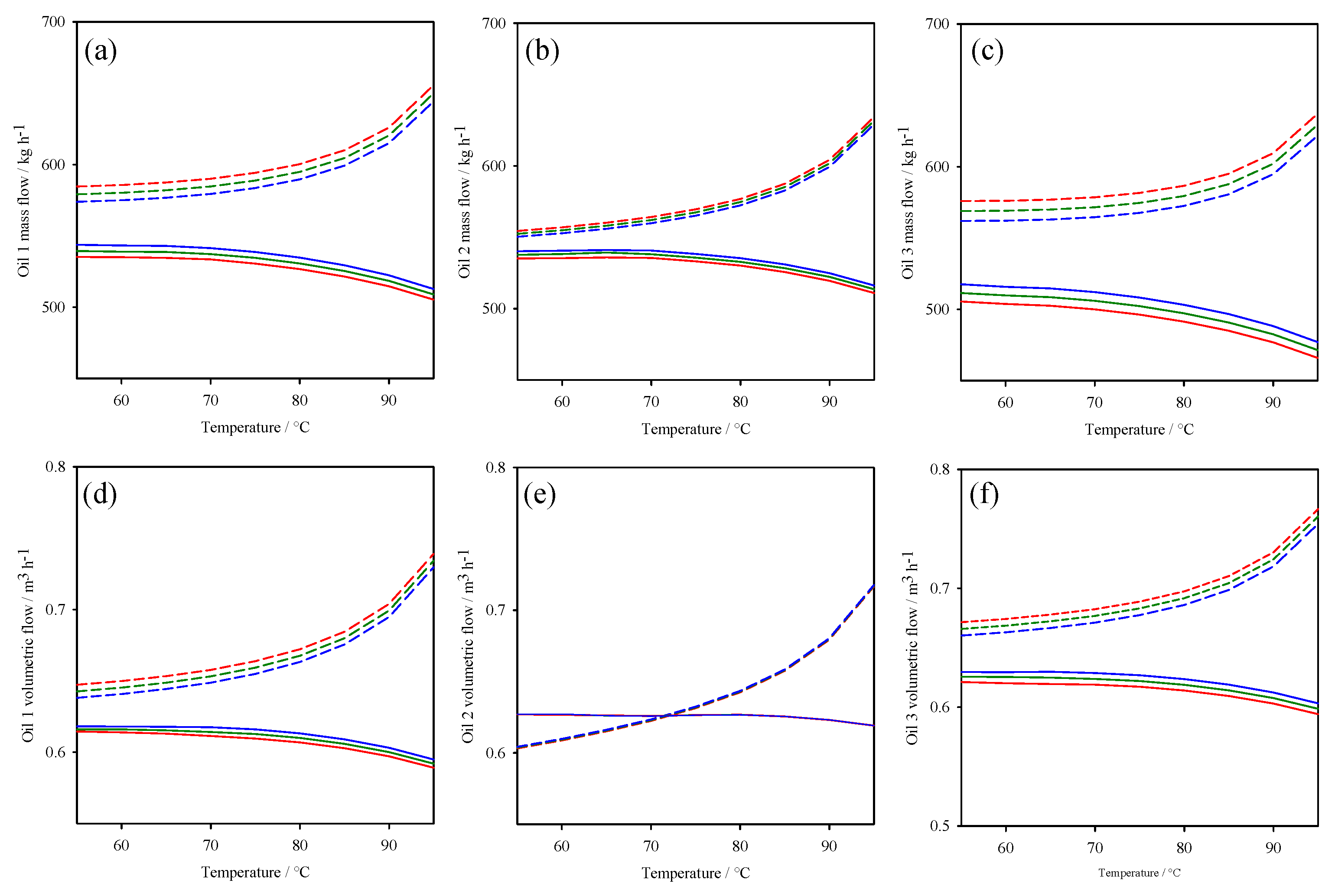

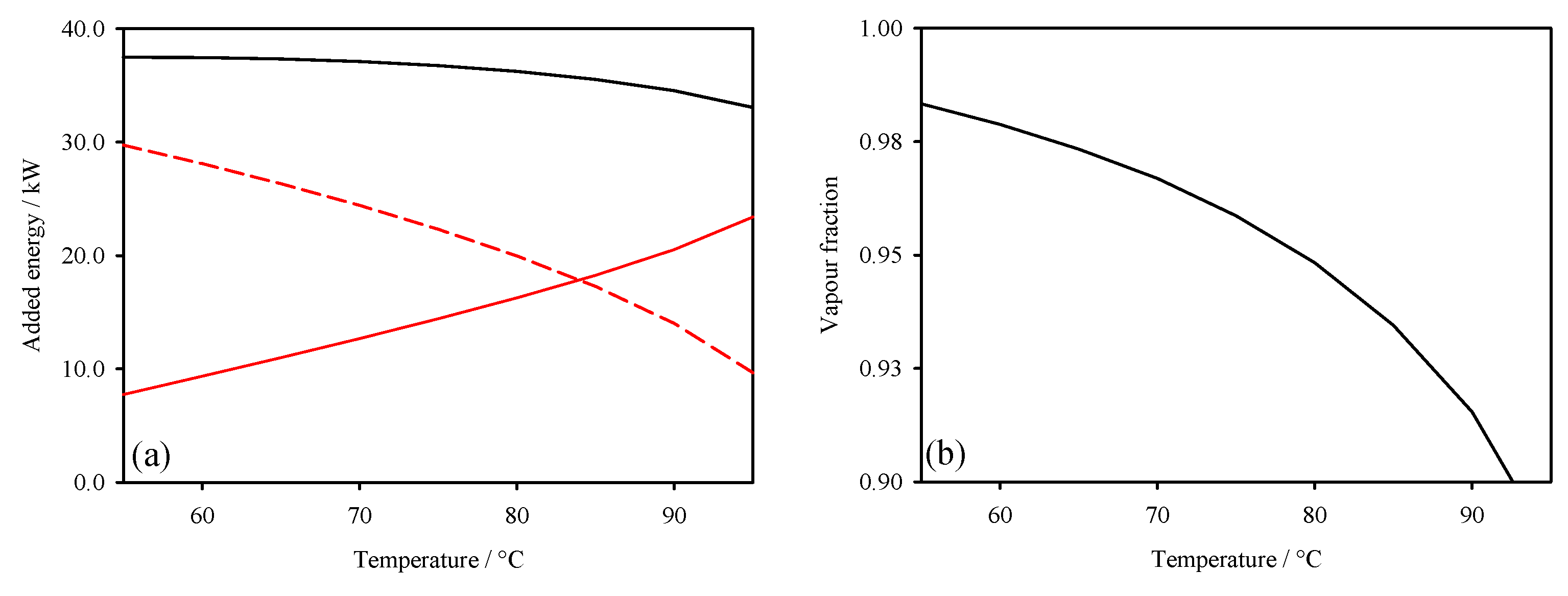

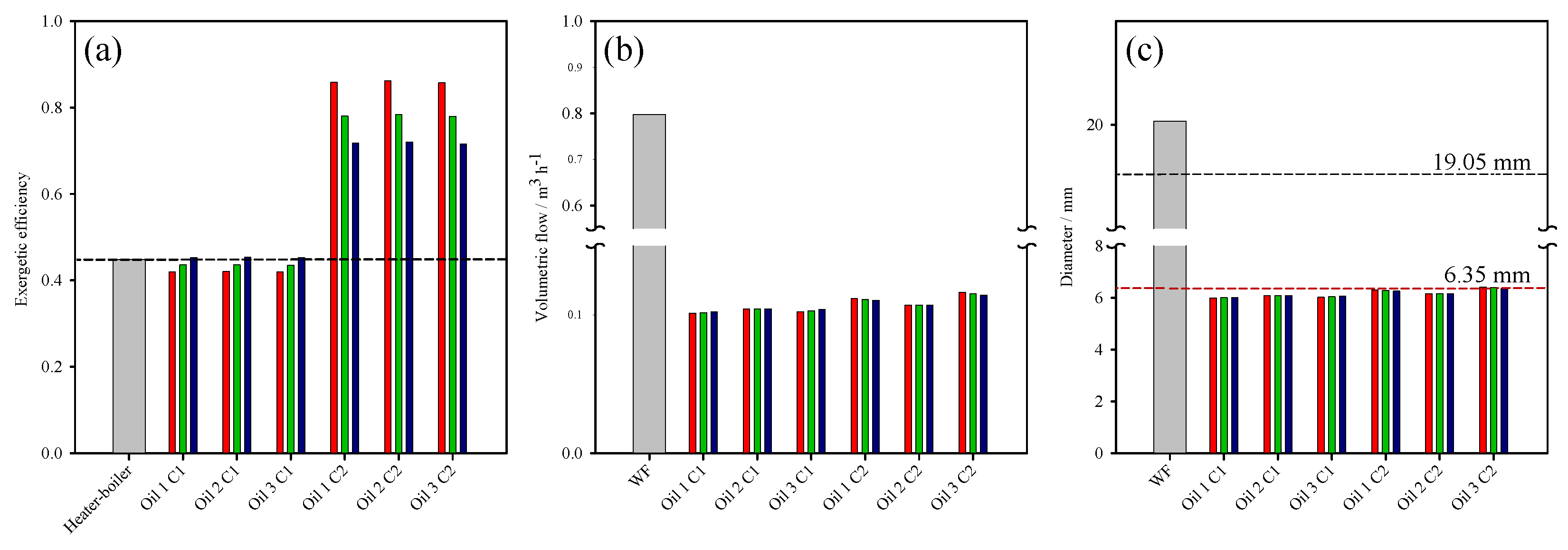

3. Thermodynamic Behaviour of ORC-TER System

4. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| C1 | Configuration 1 |

| C2 | Configuration 2 |

| GHG | Greenhouse gases |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| ORC | Organic Rankine cycle |

| TEA | Thermal Energy Accumulator |

| TER | Thermal Energy Receiver |

| WF | Working Fluid |

References

- Sorrell, S. Reducing energy demand: A review of issues, challenges and approaches. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 47, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-García, J.C.; Ruiz, A.; Pacheco-Reyes, A.; Rivera, W. A comprehensive review of organic rankine cycles. Processes 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, C.; Muritala, I.K.; Pardemann, R.; Meyer, B. Estimating the global waste heat potential. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report; IPCC, 2007.

- Goyal, A.; Sherwani, A.F.; Tiwari, D. Optimization of cyclic parameters for ORC system using response surface methodology (RSM). Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects 2021, 43, 993–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.; Garrido, J.M.; Quinteros-Lama, H. Analysis of the Maximum Efficiency and the Maximum Net Power as Objective Functions for Organic Rankine Cycles Optimization. Entropy 2023, 25, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. New classification of dry and isentropic working fluids and a method used to determine their optimal or worst condensation temperature used in Organic Rankine Cycle. Energy 2020, 201, 117722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, K.; Sircar, A. Selection of working fluid for low enthalpy heat source Organic Rankine Cycle in Dholera, Gujarat, India. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering 2019, 16, 100553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.; Llovell, F.; Garrido, J.M.; Quinteros-Lama, H. Selection of a suitable working fluid for a combined organic Rankine cycle coupled with compression refrigeration using molecular approaches. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2023, 572, 113847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronicki, L.Y. Technologies and Applications. In Organic Rankine Cycle Power Systems; Elsevier, 2017; pp. 25–66. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.T.; Chien, K.H.; Wang, C.C. Effect of working fluids on organic Rankine cycle for waste heat recovery. Energy 2004, 29, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council. Amendment to the Montreal protocol on substances that deplete the ozone layer, 2016.

- Loni, R.; et al. Waste heat recovery with ORCs: Challenges and future outlook. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.; Llovell, F.; Garrido, J.M.; Quinteros-Lama, H. A rigorous approach for characterising the limiting optimal efficiency of working fluids in organic Rankine cycles. Energy 2022, 124191, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir-Stanciu, D.; Luca, C. Solar power generation system with low temperature heat storage. Procedia Technology 2016, 22, 848–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezgi, C.; Kepekci, H. Thermodynamic Analysis of Marine Diesel Engine Exhaust Heat-Driven Organic and Inorganic Rankine Cycle Onboard Ships. Applied Sciences 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerron, G.; Nicolalde, J.F.; Martínez-Gómez, J.; Dávila, P.; Velásquez, C. Experimental analysis of a pilot plant in Organic Rankine Cycle configuration with regenerator and thermal energy storage (TES-RORC). Energy 2024, 308, 132964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniarta, S.; Nemś, M.; Kolasiński, P.; Pomorski, M. Sizing the Thermal Energy Storage Device Utilizing Phase Change Material (PCM) for Low-Temperature Organic Rankine Cycle Systems Employing Selected Hydrocarbons. Energies 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramita, P.D.P.; Daniarta, S.; Imre, A.R.; Kolasiński, P. Techno-Economic Analysis of Waste Heat Recovery in Automotive Manufacturing Plants. Applied Sciences 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolahi, M.; Yari, M.; Mahmoudi, S.M.; Mohammadkhani, F. Thermodynamic and economic performance improvement of ORCs through using zeotropic mixtures: Case of waste heat recovery in an offshore platform. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering 2016, 8, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.U.; Owes, A.; Al-Amri, F.G.; Saeed, F. Recent developments in the search for alternative low-global-warming-potential refrigerants: A review. International Journal of Air-Conditioning and Refrigeration 2020, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, S.V.; Babu, T.P. Theoretical Performance Investigation of Vapour Compression Refrigeration System Using HFC and HC Refrigerant Mixtures as Alternatives to Replace R22. Energy Procedia 2017, 109, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillner Roth, R.; Baehr, H.D. An International Standard Formulation for the Thermodynamic Properties of 1,1,1,2-Tetrafluoroethane (HFC-134a) for Temperatures from 170 K to 455 K and Pressures up to 70 MPa. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data 1994, 23, 657–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yekoladio, P.J.; Bello-Ochende, T.; Meyer, J.P. Thermodynamic analysis and performance optimization of organic rankine cycles for the conversion of low-to-moderate grade geothermal heat. International Journal of Energy Research 2015, 39, 1256–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrovedin, H.; Haghbakhsh, R.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Shariati, A. Deep eutectic solvents as phase change materials in solar thermal power plants: Energy and exergy analyses. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therminol, E. Therminol LT. https://www.therminol.com/sites/therminol/files/documents/TF-8726_Therminol_LT.pdf, 2024. Accessed: 01-07-2024.

- Paratherm, H.T.F. Paratherm HR. https://thermalprops.paratherm.com/HRFrange.asp, 2024. Accessed: 01-07-2024.

- Paratherm, H.T.F. Paratherm NF. https://www.paratherm.com/heat-transfer-fluids/paratherm-nf-htf/, 2024. Accessed: 01-07-2024.

- Bhatia, S. Advanced Renewable Energy Systems, (Part 1 and 2); Woodhead Publishing India in Energy, WPI India, 2014.

- Keenan, J.; Chao, J.; Kaye, J. Gas Tables: Thermodynamic Properties of Air Products of Combustion and Component Gases, Compressible Flow Functions; Wiley, 1980.

- González, L.; Romero, J.; Saavedra, N.; Garrido, J.M.; Quinteros-lama, H.; González, J. Heat pump performance mapping for the energy recovery from an industrial building. Processes 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshinsky, M. Chapter 5. In Manual de refrigeración; Reverté, 2012.

- Pasupuleti, R.K.; Bedhapudi, M.; Jonnala, S.R.; Kandimalla, A.R. Computational Analysis of Conventional and Helical Finned Shell and Tube Heat Exchanger Using ANSYS-CFD. International Journal of Heat and Technology 2021, 39, 1755–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Mihir M.. Shell & tube heat exchangers: Thermal design and optimization, 2023.

- Menon, E.S. Chapter 1. In Piping calculations manual; McGraw-Hill Calculations, 2005.

- González, J.; Llovell, F.; Garrido, J.M.; Quinteros-Lama, H. A study of the optimal conditions for organic Rankine cycles coupled with vapour compression refrigeration using a rigorous approach based on the Helmholtz energy function. Energy 2023, 285, 129554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Commercial name | ref | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil 1 | Therminol LT | 12.8067 | 5.5078 | 2.4950 | [26] |

| Oil 2 | Paratherm HR | 43.8256 | 2.8091 | 46.8136 | [27] |

| Oil 3 | Paratherm NF | 7.7397 | 23.0976 | –15.0726 | [28] |

| kg | kg | kg | |||

| Oil 1 | Therminol LT | 1027.42 | –0.3530 | –6.8775 | [26] |

| Oil 2 | Paratherm HR | 1188.77 | –0.7852 | 0.1843 | [27] |

| Oil 3 | Paratherm NF | 1081.53 | –0.6787 | 0.1990 | [28] |

| Value | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Organic Rankine cycle | ||

| Turbine displaced volume | – | |

| Turbine revolutions per minute | 2900.00 rpm | – |

| boiler saturation temperature | – | 330.15 to 368.15 K |

| Condenser temperature | 303.15 K | – |

| Expander isentropic efficiency | 1.0 | – |

| Pump isentropic efficiency | 1.0 | – |

| Energy source and TER | ||

| Exhaust gases temperature | – | 493.15 K to 373.15 K |

| Pinch point temperature | – | 5, 10, and 15 K |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).