Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

09 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akins, C.W.; Miller, D.C.; Turina, M.I.; Kouchoukos, N.T.; Blackstone, E.H.; Grunkemeier, G.L.; Takkenberg, J.J.; David, T.E.; Butchart, E.G.; Adams, D.H.; et al. Councils of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery; Society of Thoracic Surgeons; European Assoication for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery; Ad Hoc Liaison Committee for Standardizing Definitions of Prosthetic Heart Valve Morbidity. Guidelines for reporting mortality and morbidity after cardiac valve interventions. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008, 135, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Billiar, K.L.; Sacks, M.S. Biaxial mechanical properties of the natural and glutaraldehyde treated aortic valve cusp--Part I: Experimental results. J Biomech Eng. 2000, 122, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortolotti, U.; Milano, A.; Guerra, F.; Mazzucco, A.; Mossuto, E.; Thiene, G.; Gallucci, V. Failure of Hancock pericardial xenografts: is prophylactic bioprosthetic replacement justified? Ann Thorac Surg. 1991, 5, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotti, U.; Milano, A.; Thiene, G.; Guerra, F.; Mazzucco, A.; Valente, M.; Talenti, E.; Gallucci, V. Early mechanical failures of the Hancock pericardial xenograft. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1987, 94, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, R.J.; Deck, J.D.; Capati, B.; Nolan, S.P. The dynamic aortic root. Its role in aortic valve function. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1976, 72, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabiri, Y.; Paulson, K.; Tyberg, J.; Ronsky, J.; Ali, I.; E. Di Martino, Narine, K. Design of Bioprosthetic Aortic Valves using biaxial test data. Proceedings of IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2015, 2015, 3319–3322.

- Dabiri, Y.; Ronsky, J.; Ali, I.; Basha, A.; Bhanji, A.; Narine, K. Effects of Leaflet Design on Transvalvular Gradients of Bioprosthetic Heart Valves, Cardiovasc Eng Technol. 2016, In Press. [CrossRef]

- Dasi, L.P.; Simon, H.A.; Sucosky, P.; Yoganathan, A.P. Fluid mechanics of artificial heart valves. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2009, 36, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraiswamy, N.; Weaver, J.D.; Ekrami, Y.; Retta, S.M.; Wu, C. A Parametric Computational Study of the Impact of Non-circular Configurations on Bioprosthetic Heart Valve Leaflet Deformations and Stresses: Possible Implications for Transcatheter Heart Valves. Cardiovasc Eng Technol. 2016, 7, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Bayoumi, A.S.; Chen, P.; Hobson, C.M.; Wagner, W.R.; J.E. Mayer Jr., Sacks, M.S. Optimal elastomeric scaffold leaflet shape for pulmonary heart valve leaflet replacement. J Biomech. 2013, 46, 662–669. [CrossRef]

- Fleisher, A.G.; Lafaro, R.J.; Moggio, R.A. Immediate structural valve deterioration of 27-mm Carpentier-Edwards aortic pericardial bioprosthesis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004, 77, 1443–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, Y.C. Biomechanics: Mechanical Properties of Living Tissues. NewYork: Springer Verlag, 1993.

- Gabbay, S.; Bortolotti, U.; Wasserman, F.; Tindel, N.; Factor, S.M.; Frater, R.W. Long-term follow-up of the Ionescu-Shiley mitral pericardial xenograft. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1984, 88, 758–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamid, M.S.; Sabbah, H.N.; Stein, P.D. Influence of stent height upon stresses on the cusps of closed bioprosthetic valves. J Biomech. 1986, 19, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey, J.D.; Strumpf, R.K.; Yin, F.C. A constitutive theory for biomembranes: application to epicardial mechanics. J Biomech Eng. 1992, 114, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishihara, T.; Ferrans, V.J.; Boyce, S.W.; Jones, M.; Roberts, W.C. Structure and classification of cuspal tears and perforations in porcine bioprosthetic cardiac valves implanted in patients. Am J Cardiol. 1981, 48, 665–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ius, P.; Thiene, G.; Minarini, M.; Valente, M.; Bortolotti, U.; Talenti, E.; Casarotto, D. Low-profile porcine bioprosthesis (Liotta): pathologic findings and mode of failure in the long-term. J Heart Valve Dis. 1996, 5, 323–327. [Google Scholar]

- Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC); European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), Vahanian, A.; Alfieri, O.; Andreotti, F.; Antunes, M.J.; G. Barón-Esquivias, Baumgartner, H.; Borger, M.A.; Carrel, T.P.; M. De Bonis, Evangelista, A.; Falk, V.; Iung, B.; Lancellotti, P.; Pierard, L.; Price, S.; Schäfers, H.J.; Schuler, G.; Stepinska, J.; Swedberg, K.; Takkenberg, J.; U.O. Von Oppell, Windecker, S.; Zamorano, J.L.; Zembala, M. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012). 2012, 33, 2451–2496.

- Krucinski, S.; Vesely, I.; Dokainish, M.A.; Campbell, G. Numerical simulation of leaflet flexure in bioprosthetic valves mounted on rigid and expansile stents. J Biomech. 1993, 26, 929–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.H.; Candra, J.; Yeo, J.H.; Duran, C.M. Flat or curved pericardial aortic valve cusps: a finite element study. J Heart Valve Dis. 2004, 13, 792–797. [Google Scholar]

- Loerakker, S.; Argento, G.; Oomens, C.W.; Baaijens, F.P. Effects of valve geometry and tissue anisotropy on the radial stretch and coaptation area of tissue-engineered heart valves. J Biomech. 2013, 46, 1792–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, K.B.; Herbertson, L.H.; Fontaine, A.A.; Deutsch, S. A detailed fluid mechanics study of tilting disk mechanical heart valve closure and the implications to blood damage. J Biomech Eng. 2008, 130, 041001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Sun, W. Simulation of long-term fatigue damage in bioprosthetic heart valves: effects of leaflet and stent elastic properties. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2014, 13, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.; Sun, W. Biomechanical characterization of aortic valve tissue in humans and common animal models. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2012, 100, 1591–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercer, J.L.; Benedicty, M.; Bahnson, H.T. The geometry and construction of the aortic leaflet. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1973, 65, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, R.A.; Otto, C.M.; Bonow, R.O.; Carabello, B.A.; J.P. Erwin III, Guyton, R.A.; P.T. O’Gara, Ruiz, C.E.; Skubas, N.J.; Sorajja, P.; T.M. Sundt III, Thomas, J.D. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014, 63, e57–185. [CrossRef]

- Pibarot, P.; Dumesnil, J.G. Prosthetic heart valves: selection of the optimal prosthesis and long-term management. Circulation. 2009, 119, 1034–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reul , G.J., Jr.; Cooley, D.A.; Duncan, J.M.; Frazier, O.H.; Hallman, G.L.; Livesay, J.J.; Ott, D.A.; Walker, W.E. Valve failure with the Ionescu-Shiley bovine pericardial bioprosthesis: analysis of 2680 patients. J Vasc Surg. 1985, 2, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, M.S.; Chuong, C.J. Orthotropic mechanical properties of chemically treated bovine pericardium. Ann Biomed Eng. 1998, 26, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, M.S.; Schoen, F.J. Collagen fiber disruption occurs independent of calcification in clinically explanted bioprosthetic heart valves. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002, 62, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, M.S.; Smith, D.B.; Hiester, E.D. A small angle light scattering device for planar connective tissue microstructural analysis. Ann Biomed Eng. 1997, 25, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, M.S.; Yoganathan, A.P. Heart valve function: a biomechanical perspective. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2007, 362, 1369–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharfschwerdt, M.; R. Meyer-Saraei, Schmidtke, C.; Sievers, H.H. Hemodynamics of the Edwards Sapien XT transcatheter heart valve in noncircular aortic annuli. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014, 148, 126–132. [CrossRef]

- Schoen, F.J. Heart valve tissue engineering: quo vadis? Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2011, 22, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, R.F.; Abraham, J.R.; Butany, J. Bioprosthetic heart valves: modes of failure. Histopathology. 2009, 55, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Sacks, M.S. Finite element implementation of a generalized Fung-elastic constitutive model for planar soft tissues. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2005, 4, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiene, G.; Bortolotti, U.; Valente, M.; Milano, A.; Calabrese, F.; Talenti, E.; Mazzucco, A.; Gallucci, V. Mode of failure of the Hancock pericardial valve xenograft. Am J Cardiol. 1989, 63, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thubrikar, M.J.; Deck, J.D.; Aouad, J.; Nolan, S.P. Role of mechanical stress in calcification of aortic bioprosthetic valves. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1983, 86, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thubrikar, M.; Harry, R.; Nolan, S.P. Normal aortic valve function in dogs. Am J Cardiol. 1977, 40, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowbridge, E.A.; Crofts, C.E. Pericardial heterograft valves: an assessment of leaflet stresses and their implications for heart valve design. J Biomed Eng. 1987, 9, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacoub, M.H.; Takkenberg, J.J. Will heart valve tissue engineering change the world? Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2005, 2, 60–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, E.; Chen, J.F.; Dong, O.; Gao, S.; Massiello, A.; Fukamachi, K. Transcatheter heart valve with variable geometric configuration: in vitro evaluation. Artif Organs. 2011, 35, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesely, I. Transcatheter valves: a brave New World. J Heart Valve Dis. 2010, 19, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vesely, I. The evolution of bioprosthetic heart valve design and its impact on durability. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2003, 12, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vesely, I.; Boughner, D.; Song, T. Tissue buckling as a mechanism of bioprosthetic valve failure. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988, 46, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vongpatanasin, W.; Hillis, L.D.; Lange, R.A. Prosthetic heart valves. N Engl J Med. 1996, 335, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walley, V.M.; Keon, W.J. Patterns of failure in Ionescu-Shiley bovine pericardial bioprosthetic valves. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1987, 93, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, F.L.; Goetz, W.A.; Chong, C.K.; Chua, Y.L.; Pfeifer, S.; Wintermantel, E.; Yeo, J.H. Finite element investigation of stentless pericardial aortic valves: relevance of leaflet geometry. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010, 38, 1908–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.F.; Seco, M.; Wu, J.J.; Edelman, J.B.; Wilson, M.K.; Vallely, M.P.; Byrom, M.J.; Bannon, P.G. Mechanical Versus Bioprosthetic Aortic Valve Replacement in Middle-Aged Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.2016, 102, 315–327. [CrossRef]

- Zioupos, P.; Barbenel, J.C.; Fisher, J. Anisotropic Elasticity and Strength of Glutaraldehyde Fixed Bovine Pericardium for Use in Pericardial Bioprosthetic Valves, J Biomed Mater Res. 1994, 28, 49–57. [CrossRef]

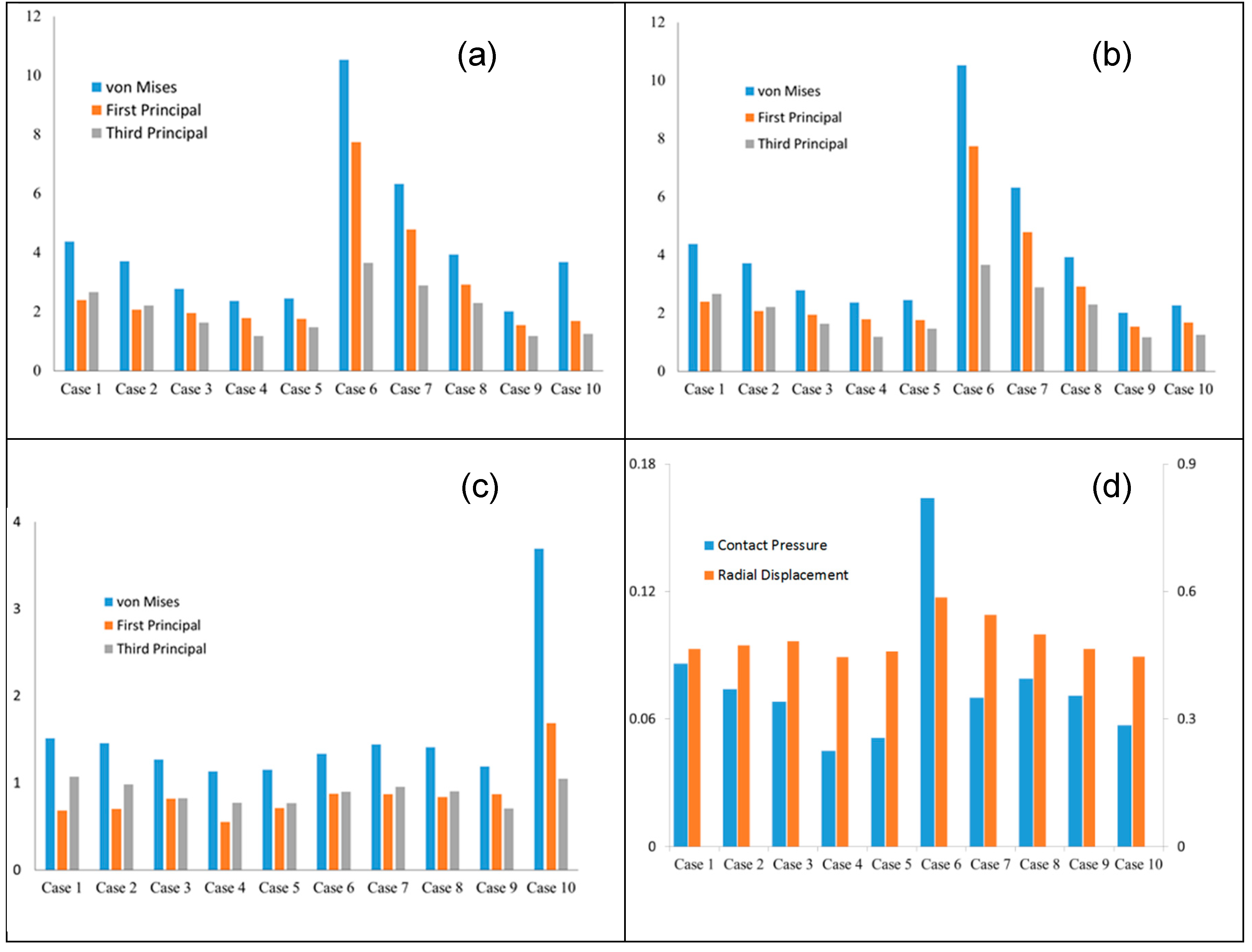

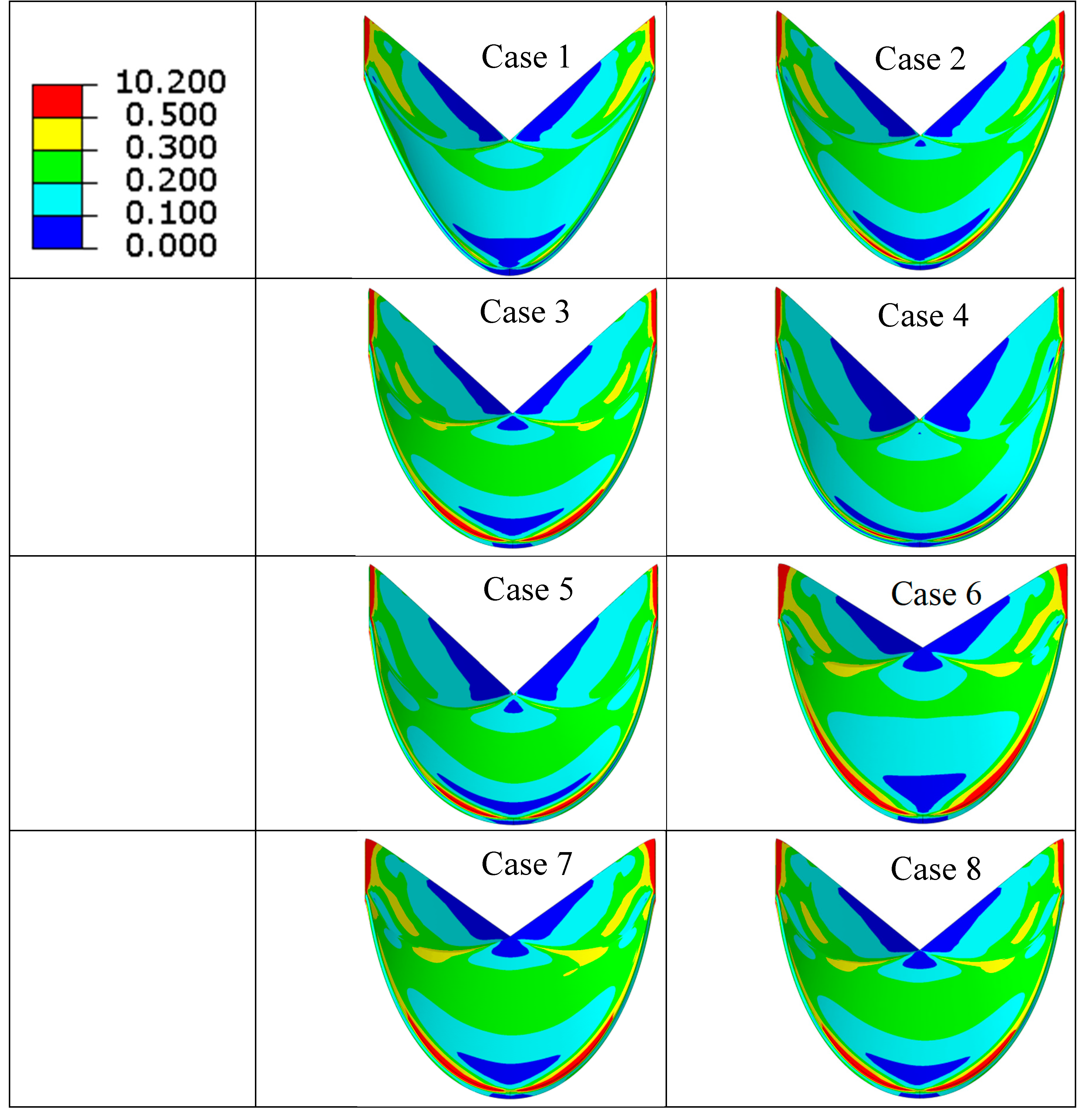

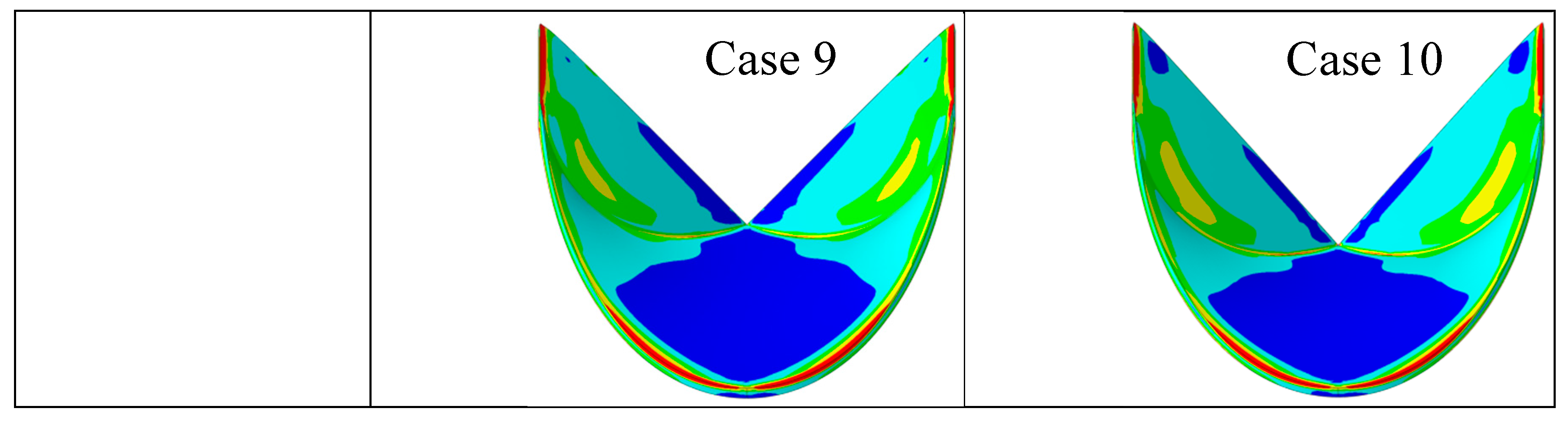

| Case number | Leaflet angle (degree) | Radial Curvature | Circumferential Curvature |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 54.4 | linear | Parabola |

| 2 | 54.4 | Linear | Spline |

| 3 | 54.4 | Linear | Circular |

| 4 | - | Parabola | Circular |

| 5 | - | Circular | Circular |

| 6 | 45.0 | Linear | Circular |

| 7 | 47.85 | Linear | Circular |

| 8 | 50.97 | Linear | Circular |

| 9 | 58.14 | Linear | Circular |

| 10 | 62.22 | Linear | Circular |

| (kPa) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8.297 | 151.375 | 0 | 56.994 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 200 | 60 | 60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).