1. Introduction

The aortic heart valve is a complex structure located in a challenging dynamic anatomical and mechanical environment. The blood flow exerts diverse stresses on the valve tissue during each cardiac cycle, which can trigger biological responses such as gene expression, protein activation, and changes to cell phenotype. This plethora of forces may also impact valve remodeling or pathological changes. Understanding the complex mechanobiology of the aortic valve involving stress–strain distribution within the leaflet thickness, remodeling cascades during the cardiac cycle, and complex biomechanical pathways of stimulus transmission from the organ to the cellular microcosm remains a challenging endeavor [

1,

2]. Understanding the geometric and biomechanical adaptation of different bioprostheses after implantation is of great clinical interest and needs to be addressed. Severe aortic valve stenosis is still the most common heart valve disease in the world [

3]. For decades,

conventional surgical AVR has been the gold standard of surgical strategy [

4,

5,

6]. Conventional AVR in patients without serious comorbidities is widely considered to be a safe procedure with a low risk of mortality [

7,

8]. However, as patients’ age and comorbidities continue to increase, conventional AVR procedures become increasingly associated with complications, particularly when combined with other procedures such as CABG [

9,

10,

11,

12]. The correlation between prolonged aortic cross-clamp and CPB times and increased mortality has been shown [

13,

14]. Consequently, rapid deployment (RDAVR) is becoming more popular due to its simplified implantation technique, proven safety, and reduced bypass and cross-clamp time [

15]. Compared to conventional valves, the Intuity aortic bioprosthesis delivers equal initial clinical outcomes, with additional hemodynamic and clinical advantages on long-term results [

16,

17]. Due to the irregular shape of the human annulus, rapid and suturless prostheses must shape it into a circle in order to achieve the best hemodynamic results and avoid early deterioration of the prosthetic leaflet [

18,

19]. All commercially available aortic heart valve devices are initially designed to be circular and perform their best when in a perfectly circular shape. However, the tissue environment exerts different external forces on the prosthesis in situ, which, in combination with other factors, such as its structural integrity, force the prosthesis into a mechanical and geometrical adaptation so that it adapts and reforms into a different shape. We therefore evaluated the Intuity aortic bioprosthesis and investigated its radial forces in vitro, and used computed tomography to describe its stent shape after implantation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

Retrospective patient data comprising clinical information prior, during, and after surgery were gathered and examined through our institution’s database. Our research was granted approval by the local ethics committee (Ethics Commission RWTH Aachen) with an Institutional Review Board (IRB) authorization: EK 151/09 version 1.2.3. As a result of the retrospective nature of the research, informed consent was not required. Patient data included medical history, postoperative echocardiographic examinations, cardiac CT scans, intraoperative data, and 30-day postoperative outcomes.

2.2. Study Cohort

This is a single-center, retrospective observational study. Data of patients who received a rapid-deployment aortic valve replacement (RDAVR) with the Intuity bioprosthesis at our Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery at RWTH Aachen University Hospital between January 2018 and December 2020 were retrieved from the institutional database and then screened. Additionally, the CT scans of these patients were analyzed, along with clinical, operative, echocardiographic, and radiographic data. All cases of RDAVR with the Intuity bioprosthesis during the above time period were included. Exclusion criteria were the presence of a bicuspid aortic valve, anatomical contraindications to RDAVR such as a dilated aortic root, endocarditis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with LV outflow tract obstruction, poor quality of the outflow tract, or incomplete data. All patients received a standardized evaluation and management, before, during, and after surgery by the same team of highly experienced experts.

2.3. Operative Technique

All patients underwent a standardized surgical procedure performed by the consistent team of cardiac surgeons. CPB was established by central aorto-caval cannulation. The best site for cross-clamp and aortotomy for the given surgical access was chosen based on the anatomy and the pathological changes of the ventriculoarterial junction, aortic root, and ascending aorta. Antegrade cardioplegia Bretschneider was administered. The aortotomy was carefully performed to ensure precise placement of the Intuity valve directly above the aortic annulus. These included variations such as a lazy-S, lazy-U, hockey-stick, strict longitudinal, and transverse types of aortotomy. In this cohort, no cases appeared with the diameter of the sinotubular junction (STJ) smaller or equal to the aortic annulus, so no opening of the aortic root was required for implantation. No high transverse incisions were required. Focal exophytic calcifications projecting into the lumen of the aortic root were delicately excised, and any damage to the aortic wall was meticulously repaired with sutures, resulting in a seamless aortic wall surface. This ensured the smooth insertion of the prosthesis into the ideal position without dislodging any remaining calcific particles.

2.4. The Intuity Edwards bioprosthesis

The Intuity RD aortic valve (Edwards Lifesciences Inc., Irvine, CA, USA) is one of the two commercially available and most frequently used RDS bioprostheses. It is implanted using the Edwards Intuity rapid-deployment application system. It is built on Perimount valve technology, with the addition of a stainless steel frame at the inflow section that is covered by a textured sealing cloth. The leaflets consist of bovine pericardium.

RDAVR with the Intuity valve is similar to conventional surgical AVR, which requires open-heart surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass to remove the calcified valve and decalcify the annulus. Unlike conventional AVR, the anchoring of the implanted Intuity valve in the annulus is not dependent on circumferential annular sutures. The Intuity design is based on the Magna Ease valve (Edwards Lifesciences), but with the addition of a balloon-expandable stainless steel stent frame covered by a polyester fabric that is attached to the inflow. Balloon inflation causes the stent frame to expand and seal against the adjacent subvalvular left ventricular outflow tract and ventriculoarterial junction [

20,

21]. The prosthesis is carefully guided into the correct position, after which the metal skirt is dilated in the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) [

22,

23,

24]. RDAVR is an attractive alternative in combined procedures and with fragile aortas, especially in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities. Multiple studies have validated and confirmed the safety and hemodynamic efficacy of the Intuity valve [

25]. After positioning the prosthesis in the correct position, the stent is expanded with a balloon in the LVOT, which helps to seal the prosthesis and secures it in the correct position. The prosthesis is available in 19, 21, 23, 25 and 27 mm [

23,

24].

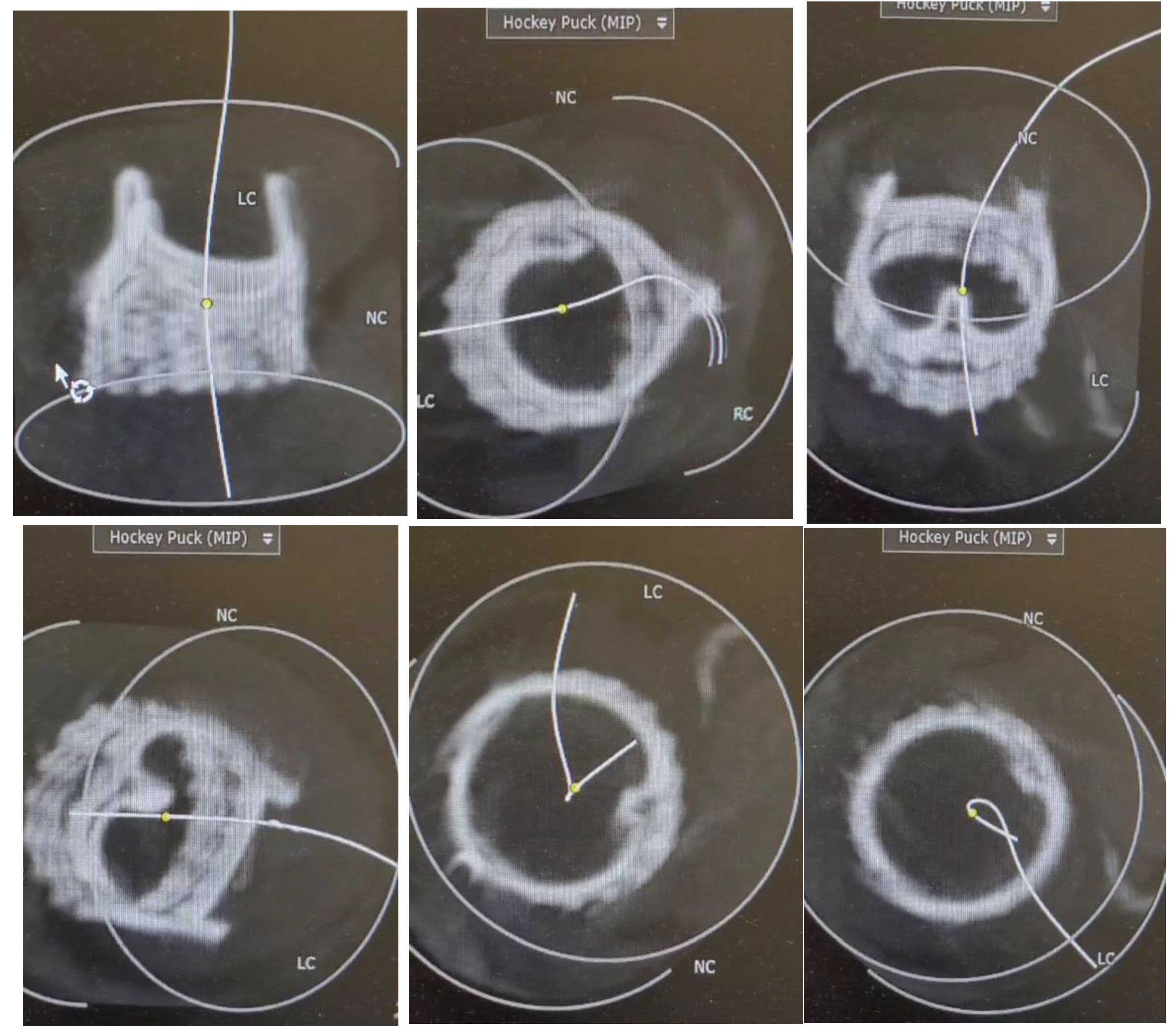

2.5. Computed Tomography Analysis

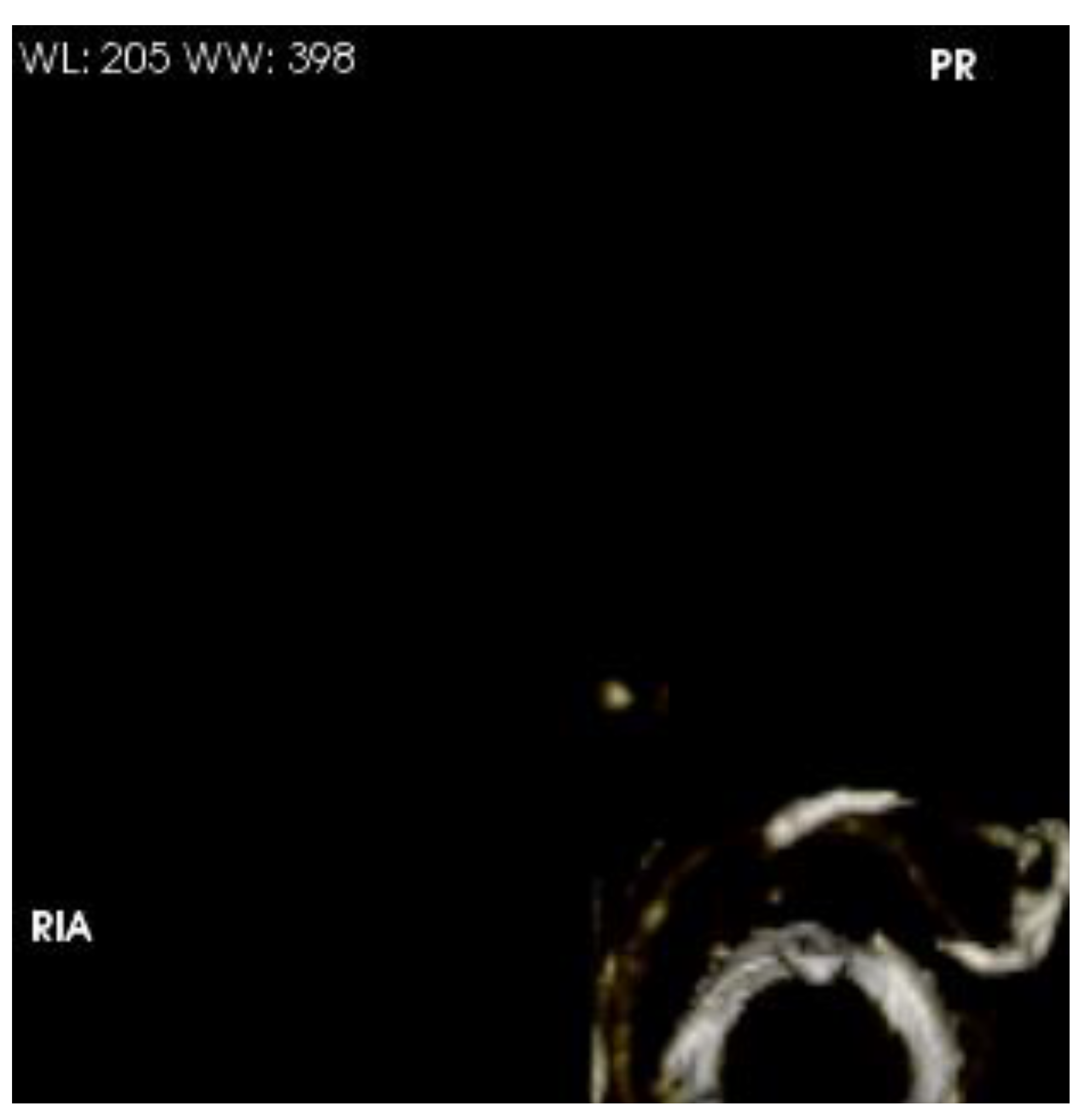

A meticulous technical assessment was conducted for each instance to evaluate the positioning, orientation, and integration of the valve with the adjacent anatomy by utilizing advanced cardiovascular 3D reconstruction software (OSIRIX DICOM Viewer © 2024 (Pixmeo SARL, Switzerland)). Two postoperative computed tomography scans were utilized for visualization and analysis. This evaluation was conducted to assess whether the Intuity valve is prone to deformation in its natural placement.

Three-dimensional analysis of the CT images after Intuity implantation was conducted using the software OSIRIX DICOM Viewer © 2024 (Pixmeo SARL, Switzerland). (

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 and Videos 1–3).

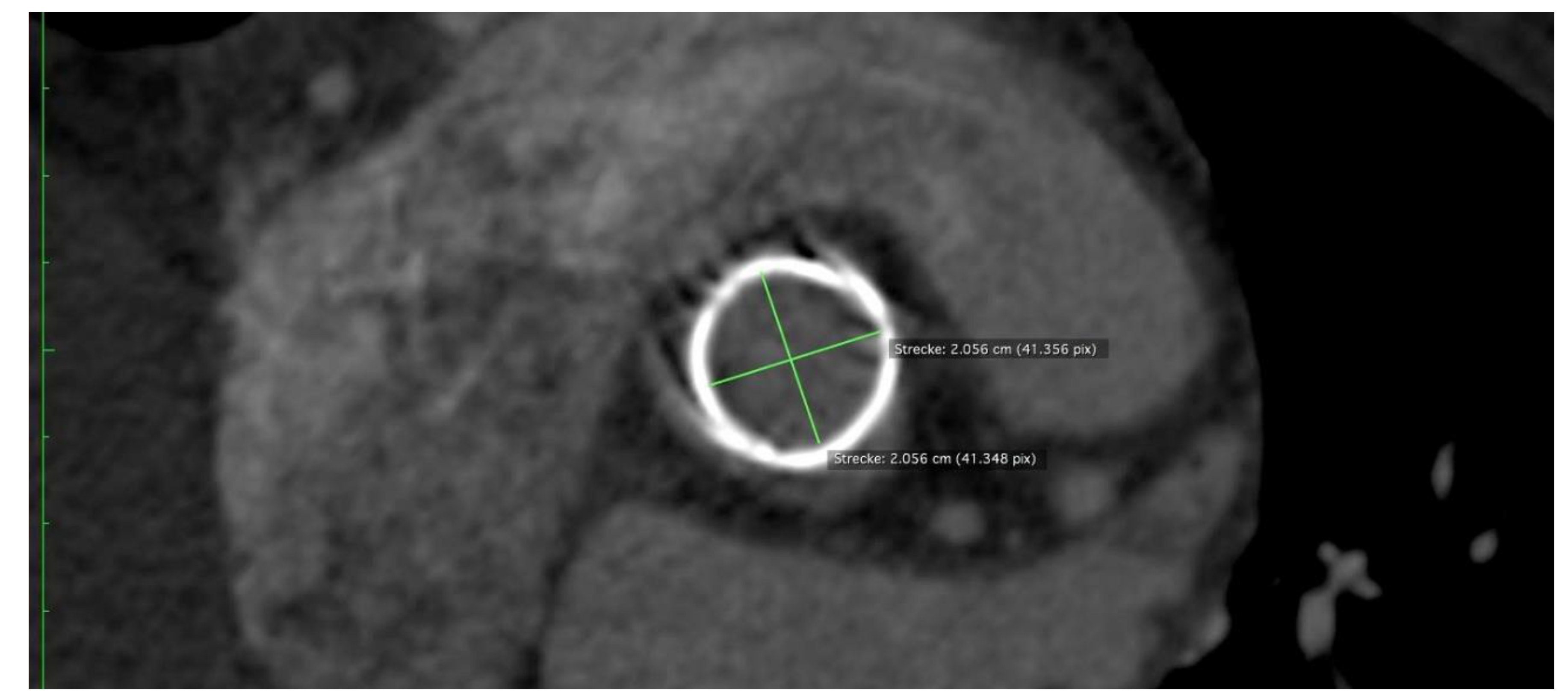

One measure to quantify the deformation of a bioprosthesis is ovality. The higher the percentage of ovality, the more oval and less circular the stent. The ovality of a circle is 0. Ovality measurements were performed at the annulus level and at the distal end of the skirt. Stent ovality

O was used as a metric for stent deformation. The percentage ovality

O can be calculated mathematically using the length of the major axis

and the length of the orthogonal minor axis

of an ellipse according to the following formula:

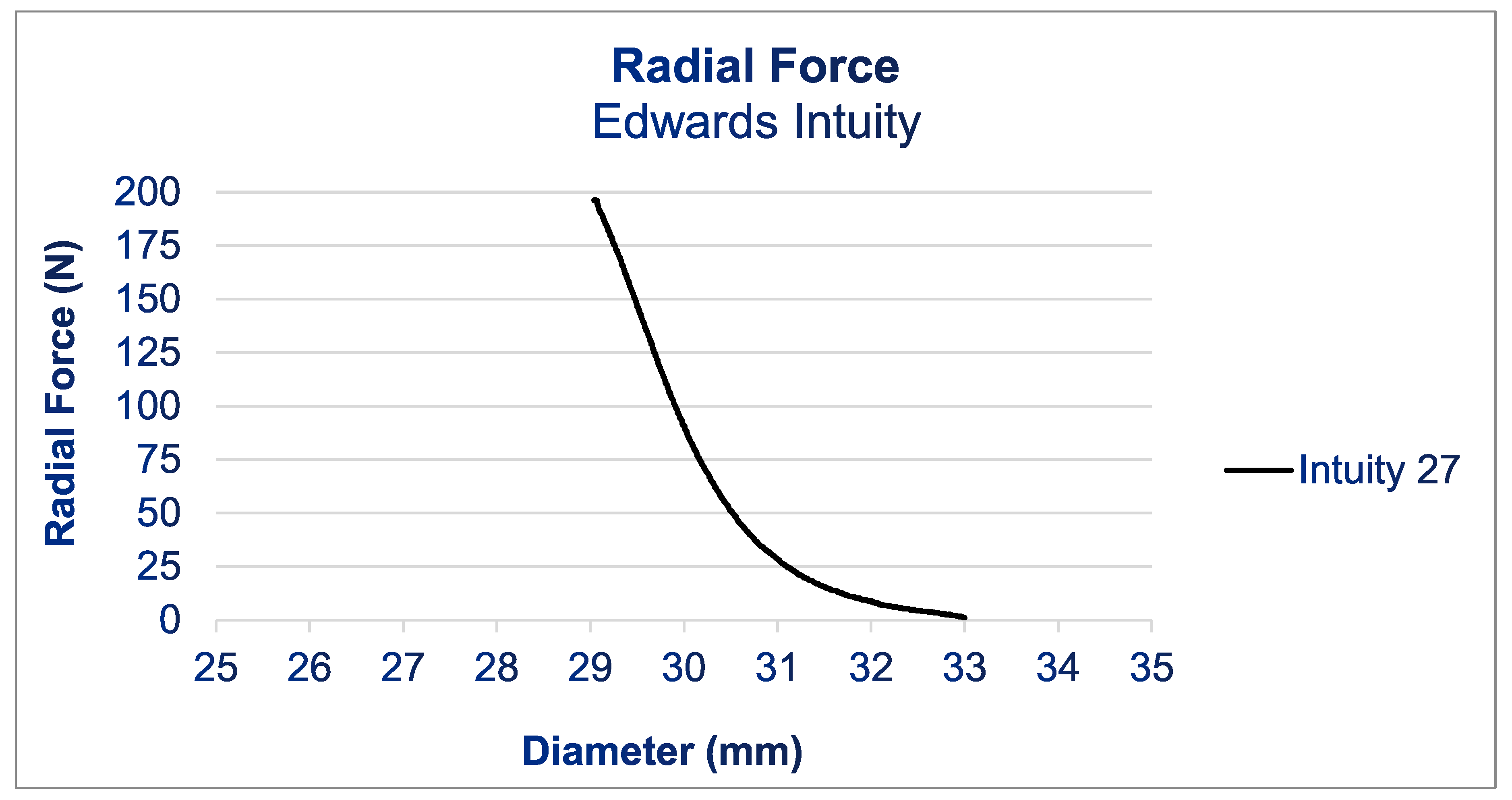

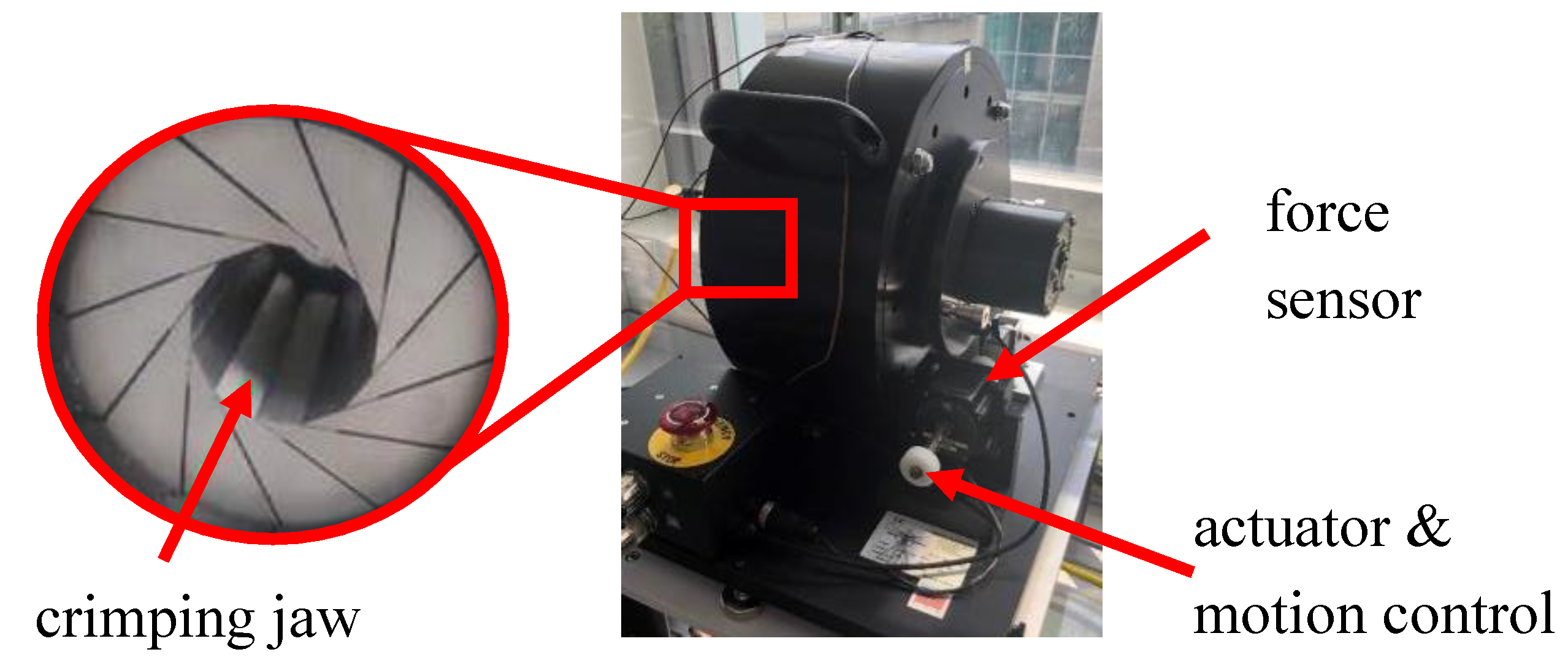

2.6. In Vitro Radial Force Assessment

Radial force (RF) is a parameter used to gauge the resistance of a stent structure to external radial deformation, as this most accurately replicates the in situ conditions (18). Measuring the RF is a common practice in the design of heart valves, and analyzing these data can provide valuable insights into the performance and behavior of a valve prosthesis in vivo [

26]. RF measurements were conducted using the commercial RF tester RX650 from Machine Solutions in Flagstaff, Arizona, USA, which is also utilized in regulatory assessments in accordance with ISO 5840-3 (see

Figure 1). A crimping mechanism consisting of 12 triangular crimping jaws opens and closes around the stent to crimp it down and let it expand, respectively. Intuity prostheses with a 27mm diameter were introduced into the tester. The tester was programmed to crimp down and compress gradually from 35 mm to 25 mm while consistently measuring the exerted RF. The manufacturer has specified the measurement accuracy of the tester as 0.06%.

2.7. Transthoracic and Transesophageal Echocardiography Assessments

Echocardiographic assessment included at least one preoperative TTE the day before surgery, an intraoperative TEE prior to CPB establishment and after CPB weaning, and a postoperative TTE control during the early postoperative period and the day of discharge. All TTE evaluations were conducted in adherence with the guidelines set forth by both the European Society of Cardiovascular Imaging and the American Society of Echocardiography [

27,

28,

29]. Echocardiographic assessments were conducted with the aid of the Vivid E9 device (GE Vingmed Ultrasound AS, Horten, Norway).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted with the software Minitab (version 19). The assessment involved utilizing both Graphical Summary and Individual Variable table tools. The Graphical Summary tool was utilized to provide a summary of numerical data, incorporating various statistics such as sample size, mean, standard deviation, confidence interval, and minimum and maximum values. The Individual Variable Table tool was employed to summarize categorical data with counts and percentages. It is important to note that certain variables contained missing values (N*) due to missing information within the dataset; these missing values were not included in Minitab during statistical calculation processes.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Findings

Between March 2018 and June 2020, a total of 19 patients (58% female) with a mean age of 76.2 years received an AVR using the Intuity bioprosthesis. Of these, N= 17/19 cases were elective cases combined with CABG, and N=2/19 cases were emergency salvage procedures due to complicated prior TAVI surgery. The postoperative rate of permanent pacemaker implantation was 5.5%. ICU stay was 8.75 ± 9.0 days, while total hospital stay was 13.9 ± 9.6 days. Detailed preoperative, operative, and postoperative findings are described in

Table 1. No severe paravalvular leakage was noted. The 30-day all-cause mortality rate of all elective RDAVR cases was 0%. In total, 2 of the 19 emergency cases in this cohort died in the ICU due to multiorgan failure and sepsis, and thus, the 30-day total mortality of this cohort was 2/19(10.5 %).

3.2. Computed Tomography Analysis

Stent ovality at the annulus level was almost 0%. Stent ovality at the distal edge of the skirt was less than 10%.

Figure 7 shows an Intuity case with an ovality of almost 0%.

3.3. Radial Force RF Measurements

Figure 1 shows the results of the RF measurements. For the Intuity prosthesis, the radial force increased gradually starting at a diameter of 33 mm during compression. Below a diameter of 31 mm, the RF increased quickly until it reached 200 N at 29 mm. The test had to be halted upon reaching 200 N, as this exceeded the load cell’s maximum capacity in the radial force tester and risked damaging the equipment.

Figure 1.

Radial force profile of an Edwards Intuity bioprosthesis case (size 27). RF tester RX650 from Machine Solutions in Flagstaff, Arizona, USA.

Figure 1.

Radial force profile of an Edwards Intuity bioprosthesis case (size 27). RF tester RX650 from Machine Solutions in Flagstaff, Arizona, USA.

Figure 2.

CT Imaging of the Intuity Elite Bioprosthesis in situ.

Figure 2.

CT Imaging of the Intuity Elite Bioprosthesis in situ.

Figure 3.

CT Imaging of the Intuity Elite Bioprosthesis in situ.

Figure 3.

CT Imaging of the Intuity Elite Bioprosthesis in situ.

Figure 4.

3D analysis shown in different ankles of the implanted Intuity Elite bioprosthesis using the 3D CT images were conducted using the software OSIRIX DICOM Viewer © 2024 (Pixmeo SARL, Switzerland).

Figure 4.

3D analysis shown in different ankles of the implanted Intuity Elite bioprosthesis using the 3D CT images were conducted using the software OSIRIX DICOM Viewer © 2024 (Pixmeo SARL, Switzerland).

Figure 5.

3D analysis shown in different ankles of the implanted Intuity Elite bioprosthesis using the 3D CT images were conducted using the software OSIRIX DICOM Viewer © 2024 (Pixmeo SARL, Switzerland).

Figure 5.

3D analysis shown in different ankles of the implanted Intuity Elite bioprosthesis using the 3D CT images were conducted using the software OSIRIX DICOM Viewer © 2024 (Pixmeo SARL, Switzerland).

Figure 6.

3D analysis shown in different ankles of the implanted Intuity Elite bioprosthesis using the 3D CT images were conducted using the software OSIRIX DICOM Viewer © 2024 (Pixmeo SARL, Switzerland).

Figure 6.

3D analysis shown in different ankles of the implanted Intuity Elite bioprosthesis using the 3D CT images were conducted using the software OSIRIX DICOM Viewer © 2024 (Pixmeo SARL, Switzerland).

Figure 7.

CT Image generated with OSIRIX showing an implanted Intuity Bioprosthesis with an ovality of almost 0%, approximating a perfect circle.

Figure 7.

CT Image generated with OSIRIX showing an implanted Intuity Bioprosthesis with an ovality of almost 0%, approximating a perfect circle.

4. Discussion

The objectives of this single-center study were to provide insights into the clinical outcome and the technical attributes of the widely used Intuity prosthesis. We found that the Intuity RD prosthesis is a proven safe alternative to traditional aortic valve replacement, with the main noticeable benefit of shorter bypass and aortic clamp times in the majority of cases, albeit at a considerably higher cost compared to the standard option, and a greater risk of new conductive system abnormalities [

25]. Several publications have compared and reported the clinical outcome of the Intuity vs. the conventional aortic valve prostheses [

17,

30]. Moreover, many reports have analyzed the hemodynamic characteristics of the RDAVR and demonstrated lower pressure gradients compared to traditional AVR in individuals receiving prosthetic valves of equivalent dimensions [

31].

In a report on 12,000 patients comparing the Intuity RDAVR to TAVR procedures, or conventional AVR with other bioprostheses, it was found that the Intuity RDAVR exhibited a 30-day mortality of only 3.8%, with no reported incidence of paravalvular leak or myocardial infarction, while an Intuity-related PPM rate of 11.11 % and a stroke frequency of 2.2% were reported [

32]. In other studies, the mortality rate with the Intuity valve has been reported to range from 0% to 3.9%. The long-term cardiovascular mortality rate for the Intuity valve is reported to vary from 0.9% to 1.55%. These clinical reports are in agreement with our clinical findings.

However, there are no studies available analyzing the biomechanical adaptation, prosthesis-annular plane adaptation, and mechanical characteristics of the Intuity bioprosthesis. The human aortic annulus is not perfectly circular [

19], and its geometry and ellipticity can influence the results of some prosthesis implantations while not affecting other alternatives [

33]. Different kinds of valve bioprosthesis interact with the surrounding tissues and in situ conditions differently based on their adaptation profiles. For example, the sutured, stented valves enforce the human annular plane into its desired circular shape, providing proper long-term performance of the cusps. In our previous study, we analyzed the biomechanics of the Perceval prosthesis [

34,

35]. In this study, our objective was to conduct a thorough analysis of not only the clinical outcomes but also the underlying morphological and functional adaptation of the Intuity Prosthesis through a comprehensive evaluation that included in vitro RF testing and in vivo 3D analysis of the maintained ovality following RDAVR. The RF results obtained from our in vitro testing indicate that the Intuity valve exhibits a high degree of rigidity, suggesting a reduced susceptibility to deformation. This is also confirmed by the low degrees of ovality found at the annulus level in the analyzed CT images. The RF of the Intuity valve at 29 mm, which is 2 mm above the upper end of its intended implantation range (200 N). Within its implantation range, the Intuity valve is potentially even more rigid, but the RF tester maxed out at 200 N and did not allow for additional measurements. However, 200 N of radial force corresponds to putting a load of 20 kg on the stent frame, which should be sufficient for its intended purpose. The Intuity bioprosthesis seems sufficiently rigid to sustain a round contour in vivo. This could explain the satisfying results, good hemodynamic performance, and low rate of patient–prosthesis mismatch even in patients with a small aortic root [

36]. The high RFs of the Intuity bioprosthesis may explain the resistance to deformation, ensuring harmonious, natural-like cusp mobility. This may reduce the risk of turbulence-induced fibrosis and increased transvalvular pressure gradients, and may clinically translate into less hemolysis. However, these generated radial forces could at the same time relate to a higher rate of postoperative conduction system disorders.

An explanation of our findings may be attributed to the expandable stainless-steel double-crimped frame cloth-covered skirt’s role in facilitating a larger orifice area for the prosthesis, which is flexible enough to be implanted and favors gentle surgical approaches. The degrees of ovality seen at the annulus level of the Intuity valve are very low because of its rigid stent frame. The skirt section shows higher degrees of ovality and less circularity than the stent section housing the valve. At the distant edge of the skirt, ovality plays a different role. The skirt is supposed to adapt to the shape of the LVOT to prevent paravalvular leakage. An irregular shape of the skirt is not problematic because it does not affect the function of the valve since the leaflets are downstream at the annulus level. This allows the skirt to adapt well to the native anatomy, decreasing the risk of paravalvular leakage. At the same time, the skirt is rigid enough to maintain its structure and provide a good hemodynamic response to the remodeling of the left ventricular outflow tract due to the infra-annular frame and freedom from Teflon-supported sutures, thus reducing turbulent flows in the left ventricular outflow tract. The manufacturer deliberately designed the skirt in such a way that it can adapt to the surrounding anatomy rather than staying perfectly round.

It should be noted that a plethora of individual characteristics and parameters, such as aortic root distensibility and aortic root stiffness, may impact the effective orifice area (EOA) and aortic valve kinematics, thereby affecting the mechanical load on the aortic valve cusps. However, the radial force profile of the different prostheses seems to have a crucial role in its clinical performance; the higher the radial force, the better the prosthesis can withstand external deformation. Deformation of the part of the prosthesis that houses the leaflets (usually at the annulus level) usually results in performance issues. In the short term, this results in incorrect opening or closing of the valve resulting in high pressures and/or regurgitation. In the medium to long term, the abnormal mechanical stress due to deformation may be seen as ovality changes in CT and lead to structural leaflet deterioration and progress from early subclinical to clinical failure of the prosthesis. For clinical practice, it might be helpful to know which prostheses are more prone to deformation and then refraining from using these prostheses in patients whose aortic root is already rather oval, e.g., on a CT scan preoperative.

Limitations of the Study

To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the few studies investigating the biomechanical adaptation of the Intuity valve. One potential limitation of our study is the small cohort size. Additionally, the data focuses on short-term measures, gathered mainly directly and up to 30 days after surgery, and does not include long-term follow-up to assess patient outcomes and valve-related data such as structural valve deterioration. Further investigation is required to determine whether these alterations have a significant impact on the onset of structural valve deterioration and the valve’s longevity [

1,

37].

5. Conclusion

The Intuity bioprosthesis demonstrates remarkable structural rigidity and, thus, the potential capacity to dynamically adjust to the hemodynamic patterns in the aortic root. The Intuity bioprosthesis demonstrates remarkably high RFs and approaches perfect circularity even in situ in the oval human annulus, which leads to satisfactory hemodynamic patterns in the aortic root postoperatively. Its high RFs at the annulus may explain the resistance to deformation, ensuring harmonious, natural-like cusp mobility. This may reduce the risk of turbulence-induced fibrosis and increased transvalvular pressure gradients, and may clinically translate into less hemolysis. To validate the clinical impact of our findings, additional research with larger samples and extended follow-up is essential.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Abbreviations

| AF |

atrial fibrillation |

| AV |

atrioventricular |

| AVR |

aortic valve replacement |

| CKD |

chronic kidney disease |

| COPD |

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| CPB |

cardiopulmonary bypass |

| EOA |

effective orifice area |

| GOA |

geometrical orifice area |

| HVD |

heart valve disease |

| HLP |

hyperlipoproteinaemia |

| IDDM |

insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus |

| ICU |

intensive care unit |

| KD |

kidney disease |

| LBBB |

left bundle branch block |

| MPG |

mean pressure gradient |

| PAD |

peripheral artery disease |

| PM |

Pacemaker |

| PVL |

paravalvular leak |

| RBBB |

right bundle branch block |

| RD |

rapid deployment |

| RDAVR |

rapid-deployment aortic valve replacement |

| RF |

radial force |

| SD |

standard deviation |

| TAVI |

transcatheter aortic valve implantation |

| TEE |

transesophageal echocardiography |

| TTE |

transthoracic echocardiography |

| PPG |

peak pressure gradient |

| PVL |

paravalvular leakage |

| TEE |

transesophageal echocardiography |

| 3D |

three-dimensional |

References

- Butcher, J.T.; A Simmons, C.; Warnock, J.N. Mechanobiology of the aortic heart valve. J Heart Valve Dis. 2008, 17, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rossini, G.; Caimi, A.; Redaelli, A.; Votta, E. Subject-specific multiscale modeling of aortic valve biomechanics. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2021, 20, 1031–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(10):e146-e603.

- Schwarz, F.; Baumann, P.; Manthey, J.; Hoffmann, M.; Schuler, G.; Mehmel, H.C.; Schmitz, W.; Kübler, W. The effect of aortic valve replacement on survival. Circulation 1982, 66, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, E.S.; Lawson, R.M.; Starr, A.; Rahimtoola, S.H. Severe aortic stenosis in patients 60 years of age or older: left ventricular function and 10-year survival after valve replacement. Circulation. 1981, 64, II184–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, O. Preoperative risk evaluation and stratification of long-term survival after valve replacement for aortic stenosis. Reasons for earlier operative intervention. Circulation 1990, 82, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahian, D.M.; O'Brien, S.M.; Filardo, G.; Ferraris, V.A.; Haan, C.K.; Rich, J.B.; Normand, S.-L.T.; DeLong, E.R.; Shewan, C.M.; Dokholyan, R.S.; et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 Cardiac Surgery Risk Models: Part 3—Valve Plus Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2009, 88, S43–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, S.M.; Shahian, D.M.; Filardo, G.; Ferraris, V.A.; Haan, C.K.; Rich, J.B.; Normand, S.-L.T.; DeLong, E.R.; Shewan, C.M.; Dokholyan, R.S.; et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 Cardiac Surgery Risk Models: Part 2—Isolated Valve Surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2009, 88, S23–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouma, B.; van der Meulen, J.; Brink, R.v.D.; Smidts, A.; Cheriex, E.; Hamer, H.; Arnold, A.; Zwinderman, A.; Lie, K.; Tijssen, J. Validity of conjoint analysis to study clinical decision making in elderly patients with aortic stenosis. J. Clin. Epidemiology 2004, 57, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iung B, Cachier A, Baron G, Messika-Zeitoun D, Delahaye F, Tornos P, et al. Decision-making in elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis: why are so many denied surgery? Eur Heart J. 2005;26(24):2714-20.

- Dewey, T.M.; Brown, D.; Ryan, W.H.; Herbert, M.A.; Prince, S.L.; Mack, M.J. Reliability of risk algorithms in predicting early and late operative outcomes in high-risk patients undergoing aortic valve replacement. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2008, 135, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Eusanio, M.; Fortuna, D.; De Palma, R.; Dell'Amore, A.; Lamarra, M.; Contini, G.A.; Gherli, T.; Gabbieri, D.; Ghidoni, I.; Cristell, D.; et al. Aortic valve replacement: Results and predictors of mortality from a contemporary series of 2256 patients. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2011, 141, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doenst, T.; Borger, M.A.; Weisel, R.D.; Yau, T.M.; Maganti, M.; Rao, V. Relation between aortic cross-clamp time and mortality — not as straightforward as expected☆. Eur. J. Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2008, 33, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sarraf, N.; Thalib, L.; Hughes, A.; Houlihan, M.; Tolan, M.; Young, V.; McGovern, E. Cross-clamp time is an independent predictor of mortality and morbidity in low- and high-risk cardiac patients. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 9, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlömicher, M.; Haldenwang, P.L.; Moustafine, V.; Bechtel, M.; Strauch, J.T. Minimal access rapid deployment aortic valve replacement: Initial single-center experience and 12-month outcomes. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015, 149, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folliguet, T.A.; Laborde, F.; Zannis, K.; Ghorayeb, G.; Haverich, A.; Shrestha, M. Sutureless Perceval Aortic Valve Replacement: Results of Two European Centers. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2012, 93, 1483–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Onofrio, A.; Cibin, G.; Lorenzoni, G.; Tessari, C.; Bifulco, O.; Lombardi, V.; Bergonzoni, E.; Evangelista, G.; Pesce, R.; Taffarello, P.; et al. Propensity-Weighted Comparison of Conventional Stented and Rapid-Deployment Aortic Bioprostheses. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2022, 48, 101426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiocchi, M.; Forcina, M.; Morosetti, D.; Pugliese, L.; Cavallo, A.U.; Citraro, D.; De Stasio, V.; Presicce, M.; Floris, R.; Romeo, F. The role of computed tomography in the planning of transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a retrospective analysis in 200 procedures. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 19, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.C.; Delgado, V.; van der Kley, F.; Shanks, M.; van de Veire, N.R.; Bertini, M.; Nucifora, G.; van Bommel, R.J.; Tops, L.F.; de Weger, A.; et al. Comparison of Aortic Root Dimensions and Geometries Before and After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation by 2- and 3-Dimensional Transesophageal Echocardiography and Multislice Computed Tomography. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2010, 3, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.H.; Jang, M.-J.; Hwang, H.Y.; Kim, K.H. Rapid deployment or sutureless versus conventional bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement: A meta-analysis. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 155, 2402–2412.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, G. The 10 Commandments of Rapid Deployment Intuity Valve Implantation. Innov. Technol. Tech. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 18, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadri, V.; Bloodworth, C.H.; Madukauwa-David, I.D.; Midha, P.A.; Raghav, V.; Yoganathan, A.P. A mechanistic investigation of the EDWARDS INTUITY Elite valve’s hemodynamic performance. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2019, 68, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhart, G.R.; Accola, K.D.; Grossi, E.A.; Woo, Y.J.; Mumtaz, M.A.; Sabik, J.F.; Slachman, F.N.; Patel, H.J.; Borger, M.A.; Garrett, H.E.; et al. TRANSFORM (Multicenter Experience With Rapid Deployment Edwards INTUITY Valve System for Aortic Valve Replacement) US clinical trial: Performance of a rapid deployment aortic valve. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016, 153, 241–251.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accola, K.D.; Chitwood, W.R.; Mumtaz, M.A.; Barnhart, G.R. Step-by-Step Aortic Valve Replacement With a New Rapid Deployment Valve. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2018, 105, 966–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, C.; Laufer, G.; Kocher, A.; Solinas, M.; Alamanni, F.; Polvani, G.; Podesser, B.K.; Aramendi, J.I.; Arribas, J.; Bouchot, O.; et al. One-year outcomes after rapid-deployment aortic valve replacement. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 155, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egron, S.; Fujita, B.; Gullón, L.; Pott, D.; Schmitz-Rode, T.; Ensminger, S.; Steinseifer, U. Radial Force: An Underestimated Parameter in Oversizing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Prostheses: In Vitro Analysis with Five Commercialized Valves. Asaio J. 2018, 64, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgartner, H.; Hung, J.; Bermejo, J.; Chambers, J.B.; Edvardsen, T.; Goldstein, S.; Lancellotti, P.; LeFevre, M.; Miller, F.; Otto, C.M. Recommendations on the echocardiographic assessment of aortic valve stenosis: a focused update from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging and the American Society of Echocardiography. Eur. Hear. J. - Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 18, 254–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for Cardiac Chamber Quantification by Echocardiography in Adults: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 16, 233–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoghbi WA, Chambers JB, Dumesnil JG, Foster E, Gottdiener JS, Grayburn PA, et al. Recommendations for evaluation of prosthetic valves with echocardiography and doppler ultrasound: a report From the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Task Force on Prosthetic Valves, developed in conjunction with the American College of Cardiology Cardiovascular Imaging Committee, Cardiac Imaging Committee of the American Heart Association, the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, the Japanese Society of Echocardiography and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography, endorsed by the American College of Cardiology Foundation, American Heart Association, European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, the Japanese Society of Echocardiography, and Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22(9):975-1014; quiz 82-4.

- Ferrari, E.; Roduit, C.; Salamin, P.; Caporali, E.; Demertzis, S.; Tozzi, P.; Berdajs, D.; von Segesser, L. Rapid-deployment aortic valve replacement versus standard bioprosthesis implantation. J. Card. Surg. 2017, 32, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghiyev, Z.T.; Bechtel, M.; Schlömicher, M.; Useini, D.; Taghi, H.N.; Moustafine, V.; Strauch, J.T. Early-Term Results of Rapid-Deployment Aortic Valve Replacement versus Standard Bioprosthesis Implantation Combined with Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2022, 71, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokollari, A.; Torregrossa, G.; Sicouri, S.; Veshti, A.; Margaryan, R.; Cameli, M.; Mandoli, G.E.; Maccherini, M.; Montesi, G.; Cabrucci, F.; et al. Pearls, pitfalls, and surgical indications of the Intuity TM heart valve: A rapid deployment bioprosthesis. A systematic review of the literature. J. Card. Surg. 2022, 37, 5411–5417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomii, D.; Okuno, T.; Lanz, J.; Stortecky, S.; Windecker, S.; Pilgrim, T. Aortic annulus ellipticity and outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 101, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljalloud, A.; Spetsotaki, K.; Tewarie, L.; Rossato, L.; Steinseifer, U.; Autschbach, R.; Menne, M. Stent deformation in a sutureless aortic valve bioprosthesis: a pilot observational analysis using imaging and three-dimensional modelling. Eur. J. Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2021, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljalloud, A.; Shoaib, M.; Egron, S.; Arias, J.; Tewarie, L.; Schnoering, H.; Lotfi, S.; Goetzenich, A.; Hatam, N.; Pott, D.; et al. The flutter-by effect: a comprehensive study of the fluttering cusps of the Perceval heart valve prosthesis. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2018, 27, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arribas-Leal, J.M.; Rivera-Caravaca, J.M.; Aranda-Domene, R.; A Moreno-Moreno, J.; Espinosa-Garcia, D.; Jimenez-Aceituna, A.; Perez-Andreu, J.; Taboada-Martin, R.; Saura-Espin, D.R.; Canovas-Lopez, S.J. Mid-term outcomes of rapid deployment aortic prostheses in patients with small aortic annulus. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2021, 33, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahren, S.E.; Winkler, B.M.; Heinisch, P.P.; Wirz, J.; Carrel, T.; Obrist, D. Aortic root stiffness affects the kinematics of bioprosthetic aortic valves. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2016, 24, ivw284–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Preoperative, surgical, and postoperative findings.

Table 1.

Preoperative, surgical, and postoperative findings.

| Variables |

|---|

| Preoperative characteristics |

|

| Age (years) |

76.26 ±6.51 |

| Female gender |

11 (58%) |

| Height (cm) |

169.1 ± 9.1 |

| Weight (Kg) |

79.7±11.6 |

| BSA |

1.9 ± 0.15 |

| EuroscoreII |

2.2 ± 0.78 |

| STS SCORE (risk for mortality) |

1.7 ± 0.72 |

| Thrombocytes (x109/L) |

261.4 ± 66.2 |

| LDH (U/L) |

254.8 ± 129.3 |

| CKD |

1 (5.2%) |

| IDDM |

5 (26.3%) |

| HLP |

4 (21%) |

| PAD |

1 (5.2%) |

| Prior AF |

5 (26.3%) |

| Prior stroke |

1 (5.2%) |

| Operative findings |

| Elective RDAVR + CABG |

17 (80.5%) |

| Salvage RDAVR as redo after TAVI |

2 (10.5%) |

| CPB time (minutes) |

157.5 ± 50.4 |

| Cross-clamp time (minutes) |

106.5 ±29.9 |

| Postoperative findings |

| ICU Stay (days) |

8.75 ± 9.0 |

| Thrombocytes (x109/L) |

178.6 ±45.8 |

| LDH (U/L) |

373.0 ± 146.7 |

| Hospital stay (days) |

13.9 ± 9.6 |

| AV block with PPI |

1(5.3%) |

| POD |

5 (26.3%) |

| MACCE |

0 |

| AF |

2 |

| 30-day mortality |

2 (10.5%) |

| In-hospital mortality |

2 (10.5%) |

| Postoperative echocardiograph findings |

| MPG (mmHg) |

10.6 ± 3.6 |

| PPG (mmHg) |

19.4 ± 6.1 |

| Velocity Ratio |

0.5 ±0.01 |

| AVAI=EOAI (VTI) cm²/ml2 |

0.8 ±0.19 |

| ET (ms) |

250.7 ±17.8 |

| AT (ms) |

75.7 ±7.2 |

| Severe PVL |

0 (0 %) |

| Mild PVL |

1 (5.2%) |

| AF: atrial fibrillation; AV: atrioventricular; AVR: aortic valve replacement; CABG: coronary artery bypass; CKD: chronic kidney disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPB: cardiopulmonary bypass; HLP: hyperlipoproteinaemia; IDDM: insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; MPG: mean pressure gradient, PAD: peripheral artery disease; PPI: permanent pacemaker implantation; POD: postoperative delirium, MACCE: major cerebrovascular events, PVL: paravalvular leak; SD: standard deviation. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).