1. Introduction

Malaria affects more than 263 million people and kills more than half million people every year, mostly African children under 5 years old [

1]. In 2023, over half a million cases were reported in the Americas, most of them in the Amazon region. Worrisome is the fact that since 2015, hardly any progress has been made to reduce malaria deaths [

1]. This means that the available tools to fight malaria are insufficient and that new strategies must urgently be implemented.

When a mosquito susceptible bites a person infected with

Plasmodium, it ingests gametocytes and becomes infected. In the insect’s midgut gametocytes are rapidly converted to male and female gametes. After fertilization, zygotes differentiate into mobile ookinetes that cross the intestinal epithelium to give rise to oocysts. Each oocyst gives rise to thousands of sporozoites that are released into the hemocoel and from there migrate to and invade the salivary glands, where they remain for the rest of the mosquito’s life [

2,

3,

4]. The low oocyst number (about 5 in field mosquitoes) represents a bottleneck of parasite development in the mosquito and affects their formation is a crucial step for blocking

Plasmodium transmission [

5]. Some gut bacteria such as

Comamonas sp.,

Acinetobacter sp.,

Pantoea sp.,

Serratia marcescens, Elizabethkingia anophelis, among others, have shown reduction of

Plasmodium falciparum oocyst load in

Anopheles gambiae [

6,

7,

8]. In particular,

Delftia tsuruhatensis [

9] and

Serratia ureilytica Su_YN1 (here forth referred to as YN1) [

10] are two mosquito microbiome bacteria that naturally (not genetically modified) strongly block the development of

Plasmodium in mosquitoes. As such, they provide much promise as a new tool for malaria control.

YN1 was isolated from wild

Anopheles sinensis from the Yunnan Peninsula in China, where the local malaria cases were lower than in other geographical regions. YN1 strongly inhibits development of the human parasite

P. falciparum and of the rodent parasite

Plasmodium berghei in

Anopheles stephensi and

Anopheles gambiae by secretion of anti-

Plasmodium lipase [

10]. Importantly, YN1 was shown to be able to spread through mosquito populations [

10]. Evaluating the potential fitness cost of a bacterium is a crucial property that needs to be considered for its potential use for control of vector-transmitted diseases.

Anopheles aquasalis is an important malaria vector in coastal regions of Brazil [

11] and South America [

12]. It can be easily maintained as laboratory colonies and has been shown to be a good model for

Plasmodium-

Anopheles interaction studies [

13,

14]. Given the YN1 potential for use in malaria transmission, we evaluated the compatibility of this bacterium with the

A. aquasalis vector, as it is not its native bacterium. We found that this bacterium is completely compatible with

A. aquasalis, as mosquito longevity, blood feeding rate, fecundity and fertility were not affected by the presence of YN1. These findings support the potential use of YN1 to fight malaria in South America.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Anopheles aquasalis

A. aquasalis mosquitoes were provided by the insectary of the Ecologia de Doenças Transmissiveis na Amazônia Laboratory. This mosquito colony has been maintained in the laboratory since 2009.

The larvae were reared in plastic containers measuring 40 cm × 12 cm × 4 cm, at a density of 100 larvae per tray. The larvae were fed with crushed and sieved TetraMin Flakes. After emerging, adults were kept in insect cages. Adult mosquitoes were maintained with 10% sucrose ad libitum at a 12h/12h day/night light cycle, 27-28 °C and 70-80% relative humidity.

2.2. Bacteria

Two bacteria species were used:

Pantoea agglomerans [

15] and

Serratia ureylitica Su_YN1 (YN1) [

10]. Electrocompetent YN1 bacteria [

16] were transformed with the plasmid pUC57-18k_GFP-HasA (3501 pb), kindly provided by Dr. Elerson Rocha. The GFP gene sequence used in this study was prospectively identified in silico in the GenBank (NCBI) database, originating from the cloning vector pBAD-GFPuv (Accession No. U62637.1). A gene expression cassette containing the constitutive PnptII promoter, E-Tag, HasA, and a terminator was then designed in silico, along with the GFP sequence. These elements were cloned into the pUC57 vector, synthesized by GenOne (Brazil). The resulting plasmid was named pUC57-18k_GFP-HasA [

17,

18,

19]. Colonies expressing green fluorescent protein were identified by exposure to UV light (

Supplementary Figure S1).

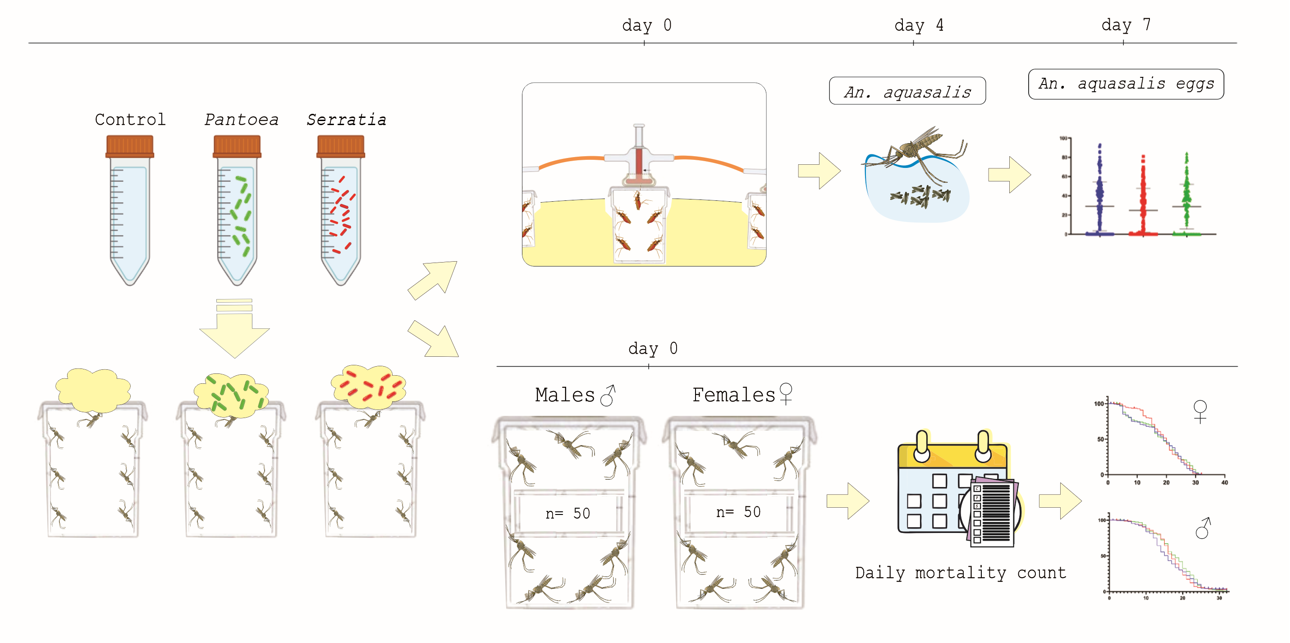

2.3. Bacterial Culture and Introduction into Mosquitoes

YN1 and P. agglomerans were cultured overnight in LB broth containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 100 μg/ml carbenicillin, centrifuged, washed three times in sterile 1x PBS and resuspended in sterile 5% (wt/vol) sucrose solution to a final 1x107 bacteria/mL-1.

Cotton pads were soaked with bacteria suspension (1x107 bacteria/mL) in sterile 5% (wt/vol) sucrose solution and provided to adult mosquitoes. After 36 h, the bacterial cotton pads were replaced with new sterile cotton pads soaked in 5% (wt/vol) sterile sucrose solution and provided to mosquitoes for two additional days. Control mosquitoes were fed exclusively with 5% (wt/vol) sterile sucrose solution. Following feeding with YN1, 100 µL of the bacteria suspension obtained from the cotton pads was plated into LB plates and checked for fluorescence 24 h later.

2.4. Effects of Different Concentrations of YN1 on the Survival of A. aquasalis

Females of A. aquasalis were fed with YN1 concentrations of 1x 105 bacteria/ml-1, 1x106 bacteria/ml-1 and 1x 107 bacteria/ ml-1 and sterile sucrose solution as control. Groups of 50 females from each treatment were separated and checked daily for mortality for 15 d. The experiments were repeated three times independently.

2.5. Effects of YN1 on the Survival of Female and Male A. aquasalis

After bacteria feeding, groups of 50 females and 50 males from each treatment (YN1, P. agglomerans and control) were separated and checked daily for mortality. This experiment was performed three independent times.

2.6. Effects of YN1 on Mosquito Blood Feeding, Fecundity and Fertility

Mosquitoes were fed with bacteria and two days later they were provided with a blood meal. The number of engorged and non-engorged mosquitoes were counted. Four days after a blood meal, 50 females from each treatment were placed in 15 ml Falcon tubes (one female/tube). The Falcon tubes had their walls covered with filter paper and the bottom filled with 7.5 ml of water to stimulate female oviposition and capped with cotton pads. The number of eggs laid by each female was counted after two days. The eggs were placed in a basin containing pure water and the hatched larvae were counted at the L2 larval stage. The eggs were placed in a basin measuring 40 cm × 12 cm × 4 cm containing 600 ml of tap water.

All experiments were performed three independent times.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

To analyze the effect of the bacteria on mosquito longevity, Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed, and

p-values defined by log-rank test (Mantel-Cox) and to evaluate the effect on the mosquito blood feeding, fecundity and fertility, we used Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons, with a significance threshold of 0.05. All data analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism v.6 software (San Diego, CA, USA,

https://www.graphpad.com/).

2.8. Ethical Statements

The experiments with bacteria were carried out at the Laboratory of Infectious Diseases and Immunology of the Postgraduate Program in Basic and Applied Immunology - PPGIBA from the Federal University of Amazonas, approved with Biosafety Level II by the National Technical Commission for Biosafety – CTNBio (CQB 095/98, technical decision no. 8714/2023). The project was registered in the National System for the Management of Genetic Heritage and Associated Traditional Knowledge (SisGen, access code A5B26D1); blood used to mosquito feeding was collected from volunteers and the procedure was approved by Research Ethical Committee (CEP UEA 6.718.957).

Results

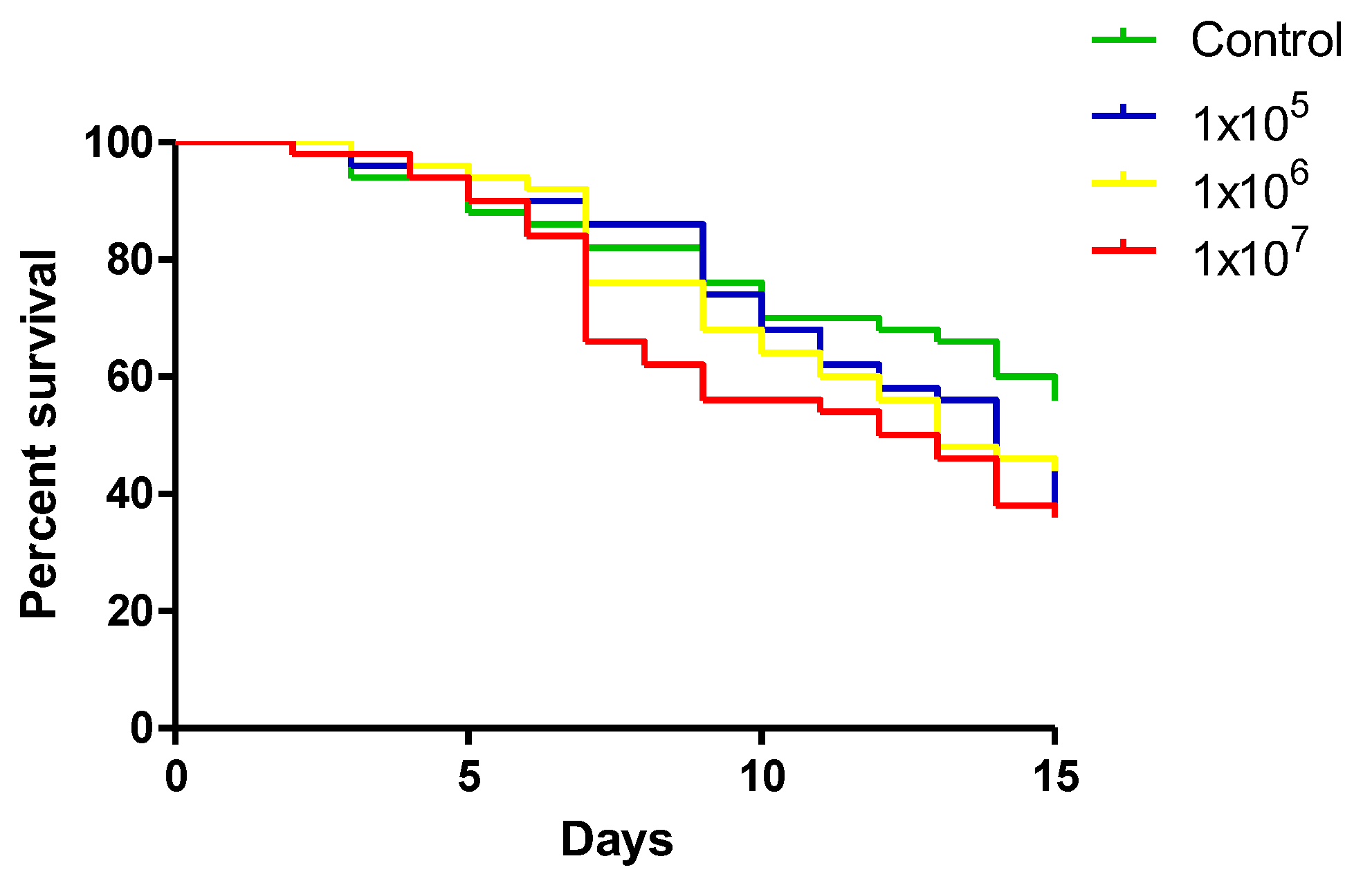

3.1. Effect of Different YN1 Concentrations on the Survival of A. aquasalis

The survival of

A. aquasalis females fed with different YN1 concentrations was evaluated. Three independent replicates were performed, each one with 50 individuals, totaling 150 females. There was no statistical difference among the analyzed concentrations (log-rank, df = 3, p = 0.2293) (

Figure 1).

We conclude that YN1 does not affect mosquito survival. The dose used for the remaining experiments was standardized to 1x 107 bacteria/ml-1.

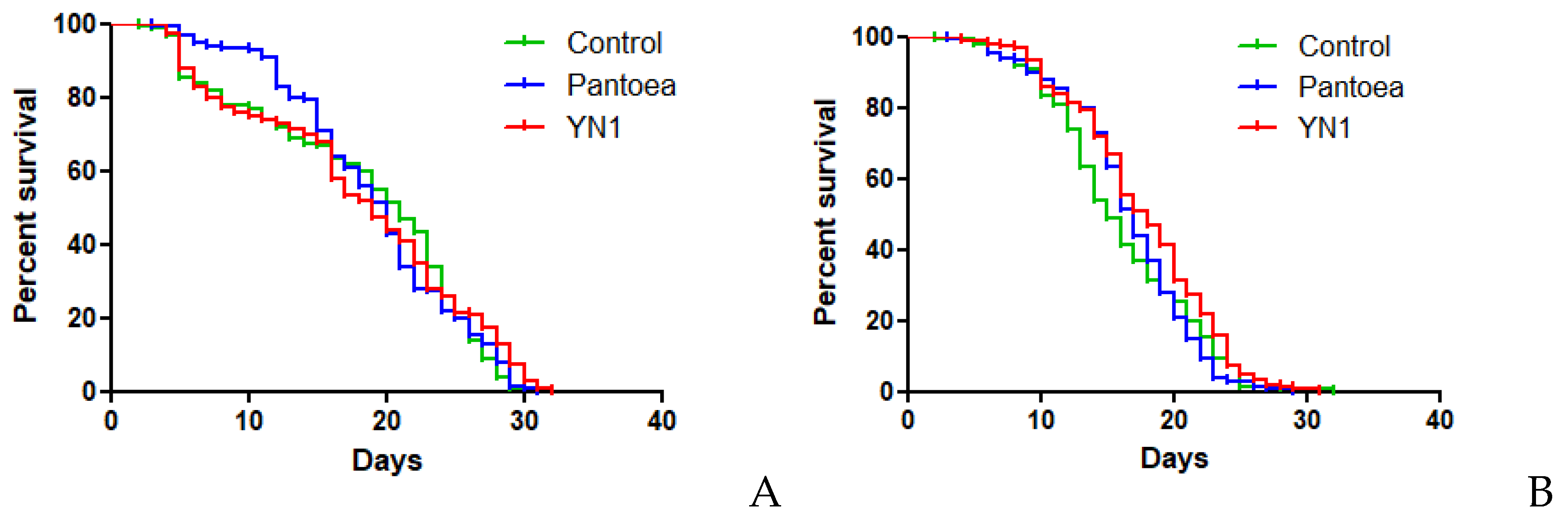

3.2. Effect of YN1 on Adult Male and Female A. aquasalis Survival

Adult female and male

A. aquasalis mosquitoes were fed with bacteria for 36 h and then monitored daily for mortality. Three independent biological replicates were performed, with 50 males and 50 females for each experiment, for a total of 900 mosquitoes. Importantly, there was no significant difference among treatments of female mosquitoes (log-rank, df = 2, p = 0.6088) (

Figure 2A), however there was significant difference for male mosquitoes (log-rank, df = 2, p = 0.0442) (

Figure 2B).

We conclude that YN1 does not affect female mosquito survival.

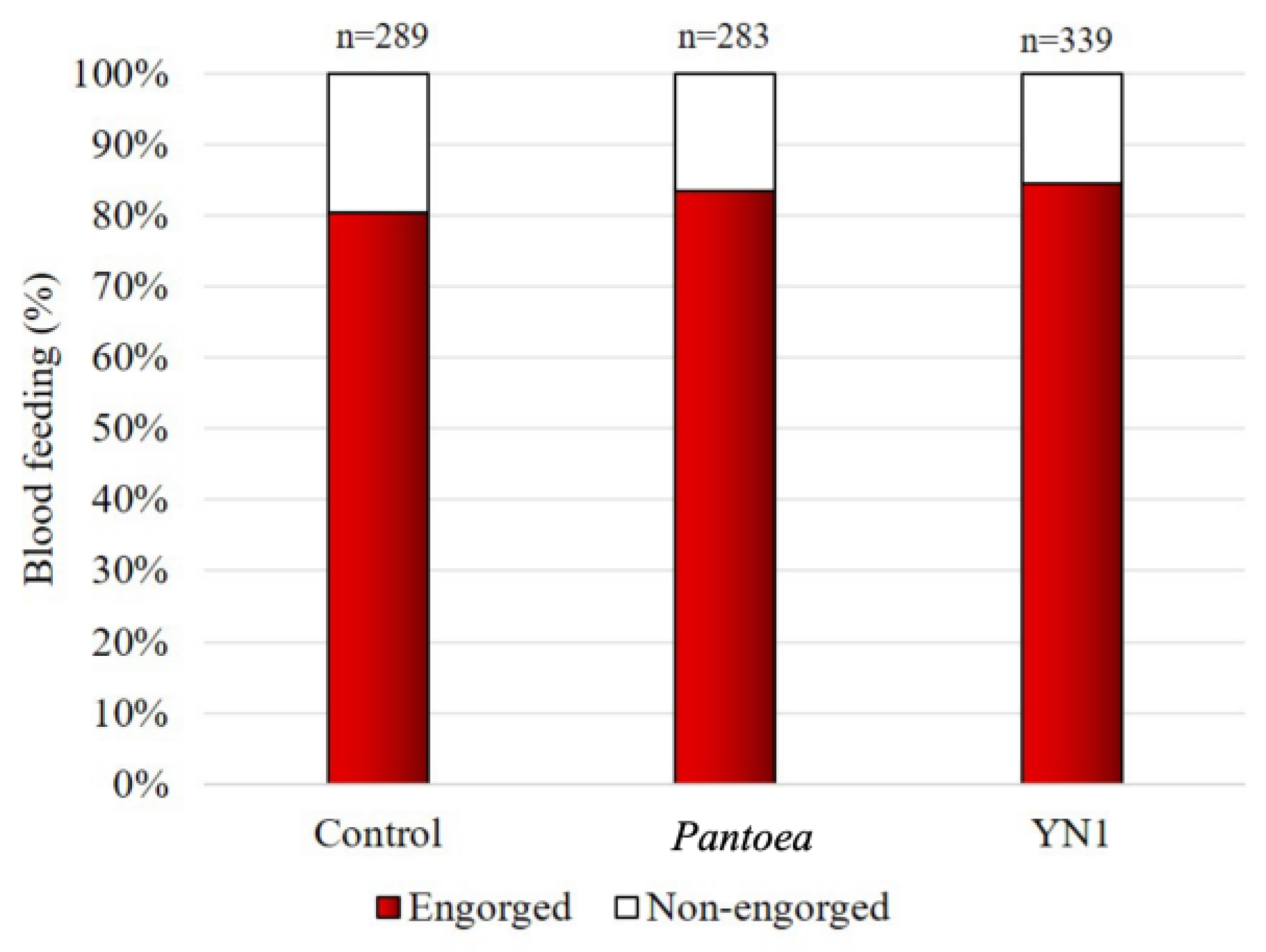

3.3. Effects of YN1 on Mosquito Blood Feeding Behavior

To investigate whether YN1 affects blood feeding behavior, female mosquitoes were provided with cotton balls soaked in sugar alone, with a

Pantoea bacteria suspension in sugar (

Pantoea was used as a mosquito symbiotic bacterium control), or with a YN1 bacteria suspension in sugar. This was followed by providing a blood meal using glass feeders. As shown in

Figure 3, there was no impact of YN1 on

A.

aquasalis blood feeding behavior (ANOVA p= 0.9536).

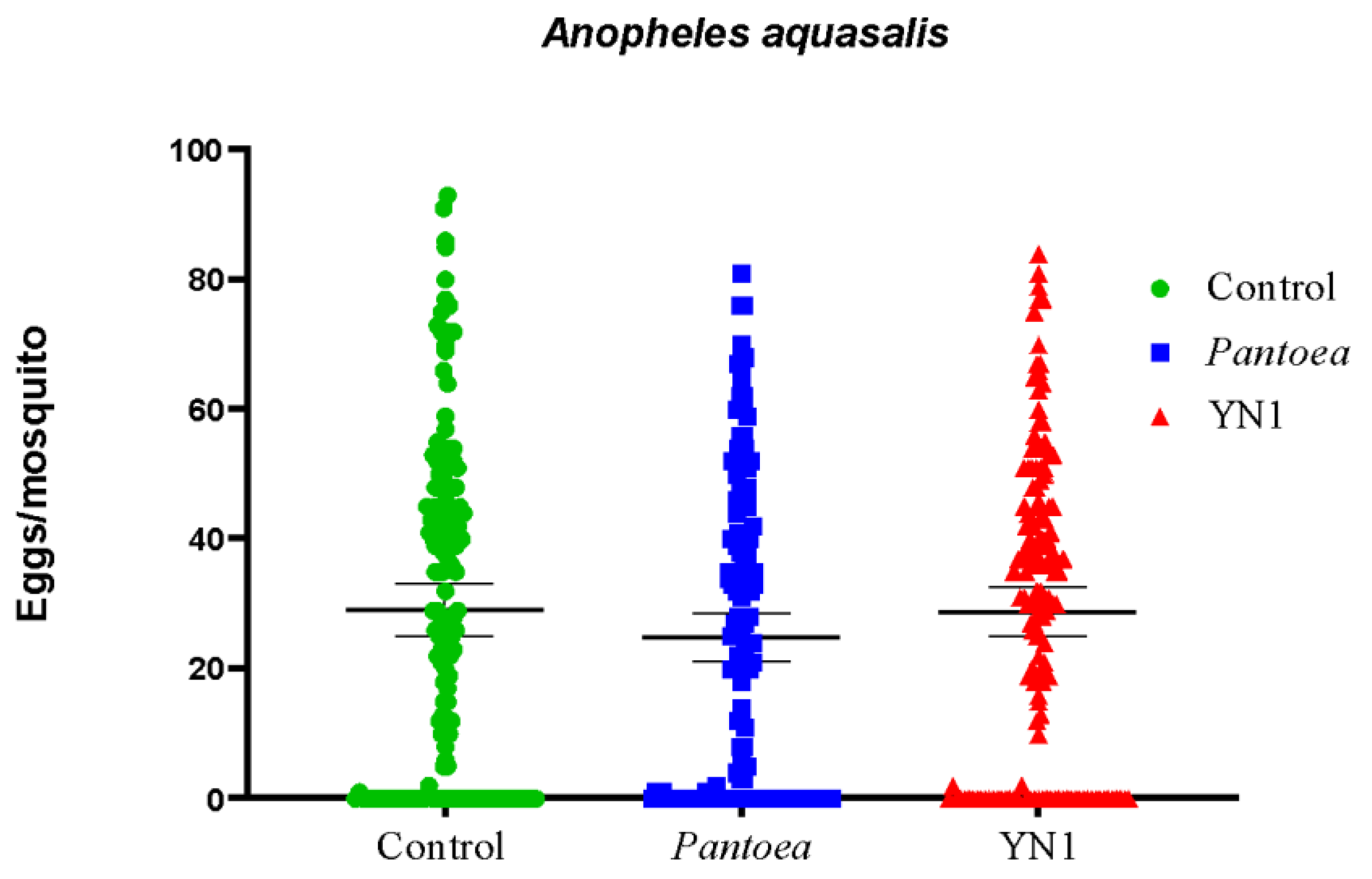

3.4. Effects of YN1 on Mosquito Fecundity

aquasalis mosquitoes were provided with cotton balls soaked with sugar alone, with a

Pantoae bacteria suspension in sugar, or with a YN1 bacteria suspension in sugar. After providing a blood meal, eggs were collected on filter papers from individual females and counted. The median number of eggs per female laid was 29 for the control group, 25 for the

Pantoea-fed females, and 30 for the YN1-fed females (

Figure 4) and there were no significant differences among the groups (Kruskal-Wallis test, p=0.3593). We conclude that YN1 bacteria do not impact

A.

aquasalis female fecundity.

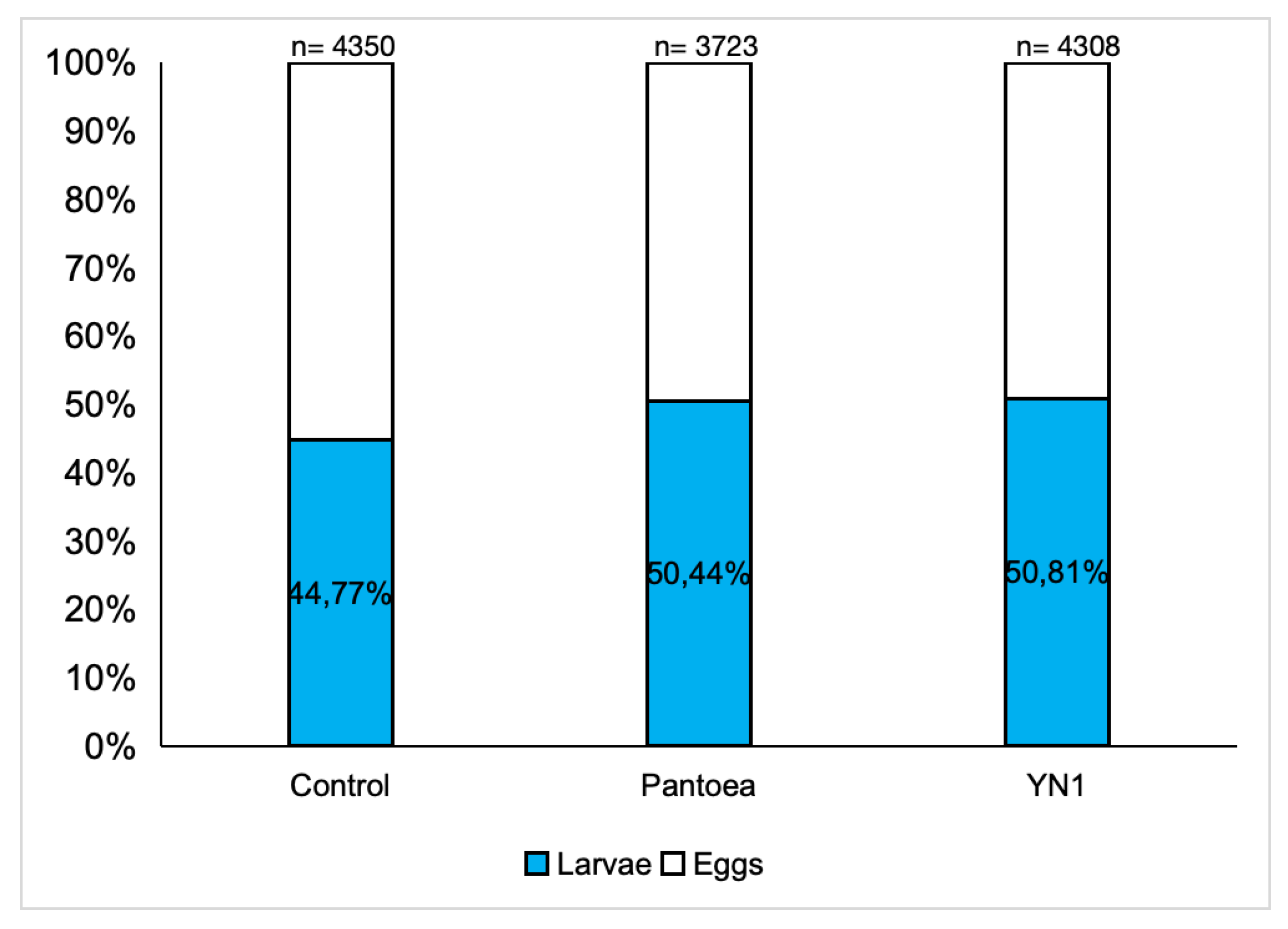

3.5. Effects of YN1 on Mosquito Fertility

This set of experiments was conducted to investigate the impact of the YN1 bacteria on the viability of eggs laid by female mosquitoes.

A. aquasalis were provided with cotton balls soaked with sugar alone, with a

Pantoea bacteria suspension in sugar, or with a YN1 bacteria suspension in sugar. After providing a blood meal, eggs were collected, reared in water, and the proportion of these eggs that developed into L2 larvae was determined. For the control group 44.8% out of 4350 eggs hatched into larvae, for the

Pantoea group 50.4% out of 3723 eggs hatched into larvae, and for the YN1 group 50.8% out of 4308 eggs hatched into larvae. There were no significant differences among the groups (ANOVA p= 0,9623) (

Figure 5). We conclude that YN1 bacteria do not impact on

A.

aquasalis female fertility.

4. Discussion

To date, only insecticides have been used in the form of insecticide-impregnated bed nets and indoor residual spraying, to suppress transmission of the malaria parasite. These approaches have been effective and were in great part responsible for the pronounced decrease of malaria deaths between 2000 and 2015 [

1]. However, effectiveness has decreased significantly, mainly due to the development of mosquito insecticide resistance and behavioral changes. As a result, little gain in mortality has occurred between 2015 and 2023 [

1]. Development of non-insecticide-based approaches to combat malaria transmission is highly desirable.

A promising new approach involves the use of symbiotic bacteria that kill early stages of

Plasmodium development in the mosquito midgut, thus blocking its transmission to humans. YN1, originally a

A. sinensis gut symbiont, has been shown to effectively suppress

Plasmodium development in various anopheline species [

10]. As such, it has great potential as a tool for blocking malaria transmission. Considering the potential to translate these laboratory findings into field-based malaria control, two YN1 key properties are that the bacterium it is not genetically modified and that it can spread through mosquito populations via horizontal and vertical transmission from one generation to the next. As an initial step to evaluate the potential of YN1 for combating malaria transmission in the Americas, we evaluated the impact of YN1 on

A. aquasalis survival, blood feeding behavior, fecundity and fertility.

We found that the bacteria YN1 does not affect any of the A. aquasalis parameters evaluated for females, even though this bacterium originated from a different continent. A. aquasalis males showed a slightly higher survival when fed with YN1, which may favor dispersal and competitiveness in nature. The egg hatching rate was between 44 and 50% in the groups evaluated. Larvae were counted at the L2 stage, avoiding manipulation of L1, and there is natural mortality within the biological cycle. In these experiments, water with iodized salt was not used, which may interfere with the larval development of the species.

Other bacteria of the genus

Serratia such as

Serratia marcescens [

20] and

Serratia AS1 were also shown to have no negative effects on the fitness of

A. gambiae, A. stephensi and

Culex pipiens [

21,

22].

Our findings suggest that YN1 may be used to control malaria in the field. However, additional studies are needed to further characterize the behavior of this bacterium in the South American vector, to its ability to spread through amazonian mosquitoes, and to determine its ability to block additional parasites, such as Plasmodium vivax.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Serratia ureilytica Su_YN1 transformed with GFP protein.

Author Contributions

Marília Andreza da Silva Ferreira: Experiments, methodology, data analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; Elen Sabrina dos Reis Martins, Ricardo de Melo Katak, Keillen Monick Martins Campos, Elerson Matos Rocha, Rosemary Aparecida Roque, Sibao Wang, Pritesh Jaychand Lalwani, Luciete Almeida Silva, Edson Júnior do Carmo: sampling design, experiments, methodology; Paulo Paes de Andrade, Luciano Andrade Moreira, Marcelo Jacobs-Lorena, Claudia María Ríos Velásquez: Conceptualization, review & editing; Luciano Andrade Moreira, Marcelo Jacobs-Lorena, Claudia María Ríos Velásquez: supervision, Claudia María Ríos Velásquez: data analysis; project administration; funding acquisition.

Funding

This work was supported by Fiocruz (Programa Inova - Call Nº04/2022), Fapeam (Programa Fixação de Jovens Doutores, call FAP/CNPq nº 003/2022, ILMD/Fiocruz (PROEP), CAPES 001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidade Estadual do Amazonas (CEP UEA 6.718.957 - CAAE 76526523.8.0000.5016 and date of approval, 22 March 2024).”.

Informed Consent Statement

“Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study (CAAE 76526523.8.0000.5016 and date of approval, 22 March 2024)”.

Data Availability Statement

All the data are presented in the manuscript. There is no additional data to share.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO, 2024. Malaria World Report. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2024.) (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Ghosh, A.; Edwards, M.J.; Jacobs-Lorena, M. The journey of the malaria parasite in the mosquito: hopes for the new century. Parasitol Today. 2000, 16, 5–196-201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baton, L.A.; Ranford-Cartwright, L.C. Spreading the seeds of million-murdering death: metamorphoses of malaria in the mosquito. Trends Parasitol. 2005, 21, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Jacobs-Lorena, M. Plasmodium sporozoite invasion of the mosquito salivary gland. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2009, 12, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.C.; Vega-Rodriguez, J.; Jacobs-Lorena, M. The Plasmodium bottleneck: Malaria parasite losses in the mosquito vector. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2014, 109, 644–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahia, A.C.; Dong, Y.; Blumberg, B.M.; Godfree Mlambo, Tripathi AK, BenMarzouk-Hidalgo OJ, et al. Exploring Anopheles gut bacteria for Plasmodium blocking activity. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 16, 2980–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tchioffo, M.T.; Boissière, A.; Churcher, T.S.; Abate, L.; Gimonneau, G.; Nsango, S.E.; et al. Modulation of Malaria Infection in Anopheles gambiae Mosquitoes Exposed to Natural Midgut Bacteria. Michel K, editor. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Manfredini, F.; Dimopoulos, G. Implication of the Mosquito Midgut Microbiota in the Defense against Malaria Parasites. PLoS Pathog 2009, 5, e1000423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Rodrigues, J.; Bilgo, E.; Tormo, J.R.; Challenger, J.D.; De Cozar-Gallardo, C.; Pérez-Victoria, I.; Reyes, F.; Castañeda-Casado, P.; Gnambani, E.J.; Hien, D.F.S.; Konkobo, M.; Urones, B.; Coppens, I.; Mendoza-Losana, A.; Ballell, L.; Diabate, A.; Churcher, T.S.; Jacobs-Lorena, M. Delftia tsuruhatensis TC1 symbiont suppresses malaria transmission by anopheline mosquitoes. Science. 2023, 381, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Bai, L.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, W.; Wang, L.; Li, S.; et al.; 2021 A natural symbiotic bacterium drives mosquito refractoriness to Plasmodium infection via secretion of an antimalarial lipase. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 806–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, B.C.; Rona, L.D.P.; Christophides, G.K.; Souza-Neto, J.A. A comprehensive analysis of malaria transmission in Brazil. Pathog Glob Health 2019, 113, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinka, M.E.; Bangs, M.J.; Manguin, S.; Rubio-Palis, Y.; Chareonviriyaphap, T.; Coetzee, M.; et al.; 2012 A global map of dominant malaria vectors. Parasit. vectors. 2012, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rios-Velásquez, C.M.; Martins-Campos, K.M.; Simoes, R.C.; Izzo, T.; Santos, E.V.; Pessoa, F.A.C.; Lima, J.B.P.; Monteiro, W.M.; Secundino, N.F.C.; Lacerda, M.V.G.; Tadei, W.P.; Pimenta, P.F.P. Experimental Plasmodium vivax infection of key Anopheles species from the Brazilian Amazon. Malar. J. 2013, 12, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimenta, P.F.; et al. An overview of malaria transmission from the perspective of Amazon Anopheles vectors. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz, 2015, 110, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Ghosh, A.K.; Bongio, N.; Stebbings, K.A.; Lampe, D.J.; Jacobs-Lorena, M. Fighting malaria with engineered symbiotic bacteria from vector mosquitoes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109, 12734–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, M.F.; Brooks, T.; Pukatzki, S.U.; Provenzano, D. Rapid Protocol for Preparation of Electrocompetent Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae. J. Vis. Exp 2013, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olah, Z.; Lehel, C.; Jakab, G.; Anderson, W. B, 1994. A cloning and ϵ-epitope-tagging insert for the expression of polymerase chain reaction-generated cDNA fragments in Escherichia coli and mammalian cells. Anal Biochem, 1994, 221, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.A.; Beattie, G.A. Bacterial species specificity in proU osmoinducibility and nptII and lacZ expression. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol, 2004, 8, 201–208. [Google Scholar]

- Alav, I.; Kobylka, J.; Kuth, M.S.; Pos, K.M.; Picard, M.; Blair, J.M.; Bavro, V.N. Structure, assembly, and function of tripartite efflux and type 1 secretion systems in gram-negative bacteria. Chem. Rev, 2021, 121, 5479–5596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezemuoka, L.C.; Akorli, E.A.; Aboagye-Antwi, F.; Akorli, J. Mosquito midgut Enterobacter cloacae and Serratia marcescens affect the fitness of adult female Anopheles gambiae s. l. PLoS ONE. 2020, 15, e0238931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koosha, M.; Vatandoost, H.; Karimian, F.; Choubdar, N.; Abai, M.R.; Oshaghi, M.A. Effect of Serratia AS1 (Enterobacteriaceae: Enterobacteriales) on the Fitness of Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) for Paratransgenic and RNAi Approaches. J. Med. Entomol.; 2018, 56, 553–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dos-Santos, A.L.A.; Huang, W.; Liu, K.C.; Oshaghi, M.A.; Wei, G.; et al.; 2017 Driving mosquito refractoriness to Plasmodium falciparum with engineered symbiotic bacteria. Science, 2017, 357, 1399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).