1. Introduction

Cabozantinib belongs to the family of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor (VEGFR-TKI) including axitinib, lenvatinib, nintedanib, pazopanib, regorafenib, sorafenib, sunitinib, and Vandetanib [

1]. These drugs act through the inhibition of multiple protein kinases, including those involved in tumor angiogenesis, oncogenesis, and tumor microenvironment (TME) [

1]. VEGFR-TKIs are employed as therapy for several malignancies [

2]. In detail, Cabozantinib demonstrated its efficacy in the treatment of various cancers such as Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC), Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma (MTC) [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

The clinical trials regarding Cabozantinib reported various adverse events (AEs) that are common to the VEGFR-TKI family, in particular hepatic and dermatological side effects [

3,

4,

5]. In literature, only a few data have been divulged about ocular AEs due to therapy with Cabozantinib or, in general, VEGFR-TKIs [

8,

9]. In this regard, only one case of corneal perforation during treatment with a VEGFR-TKI, Regorafenib, has been reported [

10]. In this paper, we present another clinical case of corneal perforation in a patient affected by advanced RCC and treated with Cabozantinib as second-line therapy. Moreover, we discuss the possible correlation between the mechanisms of action of this drug and the occurrence of this AE.

2. Cabozantinib: Mechanisms of Action, Clinical Trials, Adverse Events

2.1. Mechanisms of Action

Cabozantinib is a multi-targeted TKI. It is taken orally and exerts its effect by competitively binding to the ATP-binding site on tyrosine kinase receptors (TKRs). In detail, Cabozantinib fits into this crucial site preventing ATP from aligning correctly. It forms hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds with key amino acids within the catalytic pocket, ensuring a targeted and stable action. Thus, Cabozantinib determines the inhibition of substrate phosphorylation and, consequently, of the enzymes’ catalytic activity [

11].

The main effect of Cabozantinib corresponds to the inhibition of several TKRs playing a critical role in tumor progression. For instance, the drug inhibits neoangiogenesis by blocking Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2 (VEGFR2); this mechanism interferes with angiogenic signaling by disrupting the cascade that stimulates endothelial cell proliferation and migration. The result is a reduction of nutrients and oxygen supply to the tumor thereby slowing its growth. Furthermore, cabozantinib targets the Mesenchymal Epithelial Transition (MET) receptor which is activated by the Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF) and regulates several processes such as cell survival, proliferation, motility, and invasiveness. In detail, the inhibition of MET autophosphorylation leads to the disruption of different signaling pathways that are essential for tumor development, including those mediated by PI3K/AKT, RAS/RAF/ERK, and STAT. In addition, cabozantinib can target other TKRs, such as RET, AXL, and c-KIT [

12,

13]. The inhibition of RET is particularly useful in tumors with activating mutations, like medullary thyroid carcinoma, while blocking c-KIT and AXL inhibits cell proliferation and survival [

11].

Another mechanism of action by Cabozantinib regards the influence on the tumor microenvironment (TME). In detail, the inhibition of VEGFR2 determines a lower formation of new blood vessels and blood flow inside the tumor with the consequent development of hypoxic conditions that can further modify the features of TME [

12,

13]. Moreover, MET inhibition leads to a decrease in the release of cytokines and growth factors, rendering the microenvironment less favorable to tumor growth. Furthermore, the reduction in activation of the PI3K/AKT and RAS/RAF/ERK pathways leads to a decrease in pro-proliferative and anti-apoptotic signals [

11].

The Cabozantinib ability to target multiple kinases might offer an advantage over single-target agents, as the use of TKIs focused on a single target often causes tumor resistance. Additionally, the selective inhibition of VEGFR may trigger a compensatory upregulation of the MET pathway, promoting tumor growth. Therefore, the simultaneous inhibition of the VEGF and MET signaling pathways could prevent MET-driven resistance to single-target inhibitors and provide more effective antitumor activity than inhibiting each pathway individually [

11].

2.2. Clinical Trials

In Europe, Cabozantinib has been approved for the treatment of RCC, HCC, and MTC although this drug was tested also for other solid tumors including lung and prostate carcinoma.

2.2.1. Renal Cell Carcinoma

Cabozantinib is employed for the treatment of advanced RCC as first-line monotherapy for patients with intermediate/poor risk in terms of prognosis or combination with Nivolumab regardless of the risk group. It can be also employed as second-line therapy in those patients who have received prior VEGF-targeted therapy. These therapeutic indications derive from METEOR, CheckMate-9ER, and CABOSUN trials, respectively [

5,

6,

7].

The METEOR study evaluated the efficacy and safety of cabozantinib in patients with advanced RCC who had previously received treatment with at least one VEGFR- TKI. The goal was to compare cabozantinib versus (vs) everolimus. Patients treated with cabozantinib had a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 7.4 months vs 3.9 months of the everolimus group with a 42% reduction in the risk of progression (hazard ratio [HR] 0.58, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.45 -0.75; p<0.001). Moreover, cabozantinib improved overall survival (OS). The OS for the cabozantinib group was 21.4 months, compared to 17.1 months for patients receiving everolimus with a 34% reduction in the risk of death (HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.53-0.83; p=0.00026). The objective response rate (ORR) was 21% vs 5% in the cabozantinib and everolimus groups, respectively.

The CABOSUN study assessed the efficacy and safety of cabozantinib in patients with advanced RCC who had not previously received systemic therapy. The study compared cabozantinib to sunitinib. The median PFS for patients treated with cabozantinib was 8.2 months vs 5.6 months for those receiving sunitinib with a 34% reduction in the risk of progression (adjusted HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.46 –0.95; one-sided p = 0.012). The median OS for the cabozantinib group was 26.6 months and 21.2 months for the sunitinib group. Although the survival benefit was observed, the results did not meet the statistical threshold required to confirm a significant difference in OS. The ORR in the cabozantinib group was 46%, which was notably higher than the 27% observed with sunitinib.

The CheckMate 9ER study compared the combination of nivolumab plus cabozantinib with Sunitinib as a first-line therapy for patients with advanced RCC. Patients who received the treatment combination had a median PFS of 16.6 months, significantly longer than the 8.4 months observed in the sunitinib group. This translated to a 41% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death for the combination group [HR 0.59; 95% CI 0.49-0.71]. The combination treatment also showed a significant improvement in OS (49.5 vs. 35.5 months; HR 0.70; 95% CI 0.56-0.87). Although this result was still maturing, it suggested a potential for a 31% reduction in the risk of death for the combination therapy. The ORR was 56% vs 28% in the combination group and sunitinib group, respectively.

2.2.2. Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Cabozantinib is employed for the treatment of HCC in those patients who have progressed to Sorafenib.

The CELESTIAL trial [

3] tested the efficacy and safety of cabozantinib vs Placebo in patients with advanced HCC who had previously received Sorafenib. Cabozantinib significantly improved PFS compared to placebo (5.2 months, vs 1.9 months; adjusted HR 0.44, 95% CI 0.36–0.52; p < 0.0001). Patients treated with cabozantinib had a median OS of 10.2 months, compared to 8 months for those receiving placebo (HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.63–0.92; p = 0.005). The ORR for cabozantinib was 4%, vs 1% seen in the placebo group (p=0.009).

2.2.3. Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma

Cabozantinib is employed for the treatment of progressive, unresectable locally advanced, or metastatic MTC.

The EXAM study [

4] was a phase III clinical trial designed to test cabozantinib vs placebo in patients with progressive, metastatic MTC who had received prior treatment. The results showed that cabozantinib significantly improved PFS compared to placebo (11.2 months vs. 4 months; HR 0.28, 95% CI 0.19–0.40; p < 0.001). The ORR in the cabozantinib group was 28% vs 0% in the placebo group (p < 0.001). Median OS was 26.6 months in the cabozantinib group vs 21.1 months in the placebo group (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.64-1.12; p = 0.2409). An exploratory analysis of about 65% of patients with known RET M918T mutations showed that the median OS was 44.3 months in the cabozantinib group and 18.9 months in the placebo group (HR 0.60, 95% CI 0.38 -0.94; p = 0.026). This subgroup of patients was also noted to have the longest median PFS and highest ORR.

2.3. Adverse Events

Cabozantinib, like other TKIs, is associated with a range of AEs, some of which can be quite common, while others are less frequent but more serious. Many of these AEs are manageable with proper monitoring and adjustments to the treatment regimen [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

11].

One of the most common AEs of cabozantinib is diarrhea, which affects around 54-75% of patients. While most cases are mild, about 7-21% of patients experience severe diarrhea (grade 3 or 4). Another frequent side effect is fatigue, reported in approximately 40-60% of patients. This can range from mild tiredness to more debilitating fatigue, with 10% of patients experiencing severe levels (grade 3-4). Hypertension is also common, affecting around 37-65 % of patients on cabozantinib. In about 10-20% of patients, the hypertension becomes severe (grade 3 or 4). Hand-foot syndrome (HFS), also known as palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, is another frequent AE, occurring in around 45-65% of patients with 8-17% of grade 3-4 AEs. It typically causes pain, redness, and swelling on the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet. Weigh loss is observed in 35-60% of patients with 3-9% of severe grade. Nausea is experienced by about 30-50% of patients taking cabozantinib, though it is generally mild. In about 3-5% of cases, nausea becomes severe (grade 3 or 4). Vomiting occurs in 25-30%with 1-2% of G3-G4. Another side effect that can occur in a significant proportion of patients is hair color changes which affects around 35% of individuals on cabozantinib. Decreased appetite and dysgeusia are another concern, affecting 40-45% of patients, with 2-4% experiencing a severe AE. A potential issue that requires careful monitoring is liver enzyme elevation, which occurs in 22-30% of patients. Although severe liver toxicity (grade 3-4) affects 5-8% of patients, it is crucial for healthcare providers to regularly monitor liver function. Constipation is another side effect, seen in 20-25% of patients. While usually manageable with laxatives or dietary changes, severe constipation (grade 3-4) can occur in a smaller subset of patients. Some patients may experience hypothyroidism. This occurs in about 23-37% of patients and is usually manageable with appropriate thyroid hormone replacement therapy.

Furthermore, there is a series of AEs that occurs in almost 10-25% of patients but usually in a mild grade: dyspepsia, dizziness, dysphonia, hyperglycemia, stomatitis, rash, blood creatinine increased, proteinuria, anemia, thrombocytopaenia, neutrophil count decreased, asthenia, abdominal pain, cough, peripheral edema, and ascites.

Rarely, in almost 1-2% of cases, patients may experience hemorrhagic events (usually epistaxis), intestinal perforation, and arterial or venous thromboembolism (blood clots, stroke, heart attack, pulmonary emboli) which are severe complications.

3. Clinical Case

In October 2022, a 78-year-old male patient came to our attention at the Oncology Unit of the “S. Croce and Carle” Hospital in Cuneo (CN), Italy. He was experiencing stabbing pain at the sternum. A total body computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a mass of 3 cm in the right kidney and several metastases involving lungs, lymph nodes, and bones, including one in the sternal body. A biopsy of the sternum was performed; the histological examination confirmed clear cell renal carcinoma (CCRC).

By the guidelines, since December 2022 the patient has been undergoing treatment with Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib. In August 2023, the first follow-up CT scan was performed showing an increase in the number of bone and lung metastases. In consideration of disease progression, treatment with Cabozantinib was proposed based on the results of the METEOR trial [

5]. The patient started therapy at the dosage of 60 mg/die although he experienced some grade 2 AEs (according to CTCAE v6.0) including asthenia, diarrhea, dysgeusia, and loss of appetite. Therefore, it was necessary to repeatedly apply dose reductions. First, with the schedule of 5 days ON (60 mg) and 2 days OFF, later with the dosage of 40 mg/die and, finally, another time with the schedule of 5 days ON (40 mg) and 2 days OFF. The last strategy was well tolerated and was continued.

In December 2023, the follow-up CT scan documented a numerical and dimensional reduction of the metastases. Therefore, treatment with Cabozantinib was continued and the subsequent CT scans showed stable disease.

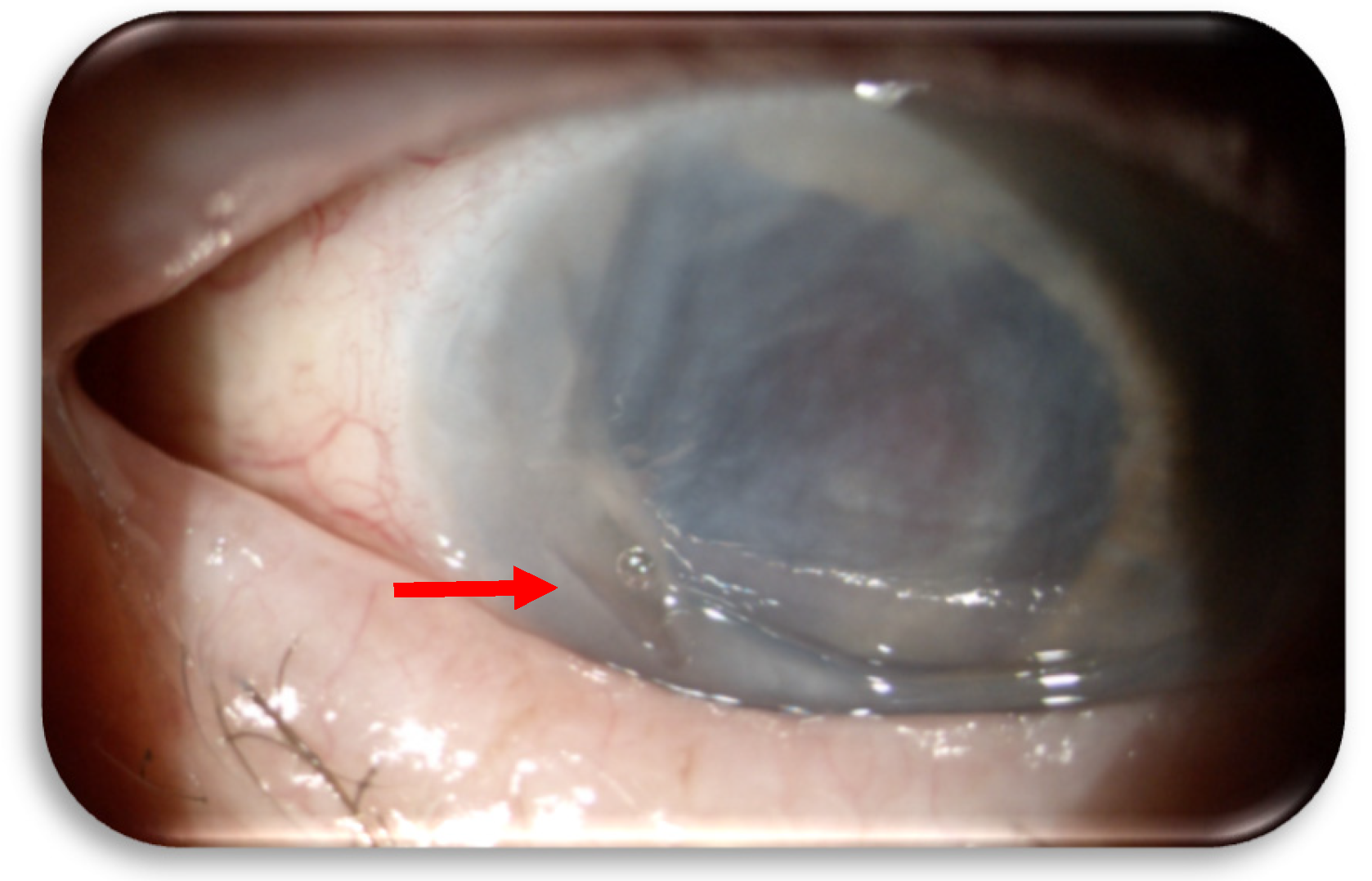

In December 2024 (at 15 months from cabozantinib start), the patient began to experience pain and vision loss in the right eye, so he was visited at the Ophthalmology Unit of “S. Croce and Carle” Hospital. The patient suffered from a marginal corneal ulcer on the right eye. Topical therapy with ophthalmic ointment containing chloramphenicol 0,4%, colistin, and tetracycline 0,4% (Colbiocin, Sifi Spa) was initiated and continued for one month until the ulcer re-epithelialized. The dose and administration scheme of cabozantinib were not modified. Furthermore, the right eye had a history of multiple surgeries for trauma, leaving residual visual acuity of counting fingers. However, in January 2025, the patient returned to the Ophthalmology Unit before the scheduled follow-up visit due to worsening of the clinical condition. A recurrence of the ulcer was identified, this time with perforation of the cornea (

Figure 1). Cabozantinib was suspended, a therapeutic contact lens was immediately fitted, and topical therapies with moxifloxacin 0.5%, netilmicin 0.3%, and atropine 1% drops were initiated.

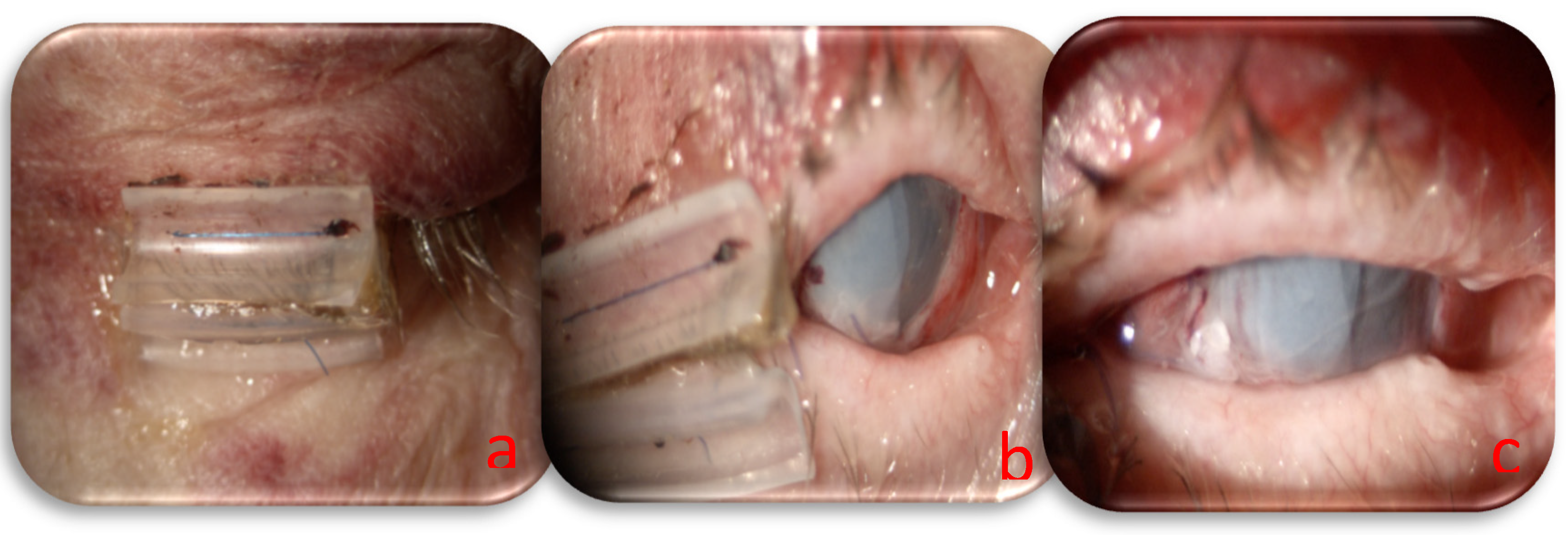

Based on the systemic condition of the patients and the necessity to continue oncological treatment, we decided to perform urgent surgery and a combined approach with human amniotic membrane (HAM) to close the corneal perforation and lateral tarsorrhaphy to reduce ocular exposure and increase the healing process. The HAM was sutured to the limbus using a 10/0 nylon suture to guarantee perfect corneal closure, and a triple layer was used to increase the permanence on the perforated area. The tarsorrhaphy was made with absorbable 6/0 sutures (Vicryl, Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson) on the tarsal plate and non-absorbable 6/0 sutures with a silicon hose (Vicryl, Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson) on the anterior eyelid margin; the use of a mixed suture allowed us to regulate the timing and grade of eyelid aperture during recovery. The day following surgery, residual visual acuity was assessed as hand motion, amniotic membranes were appropriately positioned, and the anterior chamber was filled with aqueous humor, indicating successful closure of the corneal perforation (

Figure 2). Postoperatively, a topical regimen comprising moxifloxacin 0.5% (Vigamox, Alcon), netilmicin 0.3% (Nettacin, Sifi spa), atropine 1%, and ocular lubricants was established.

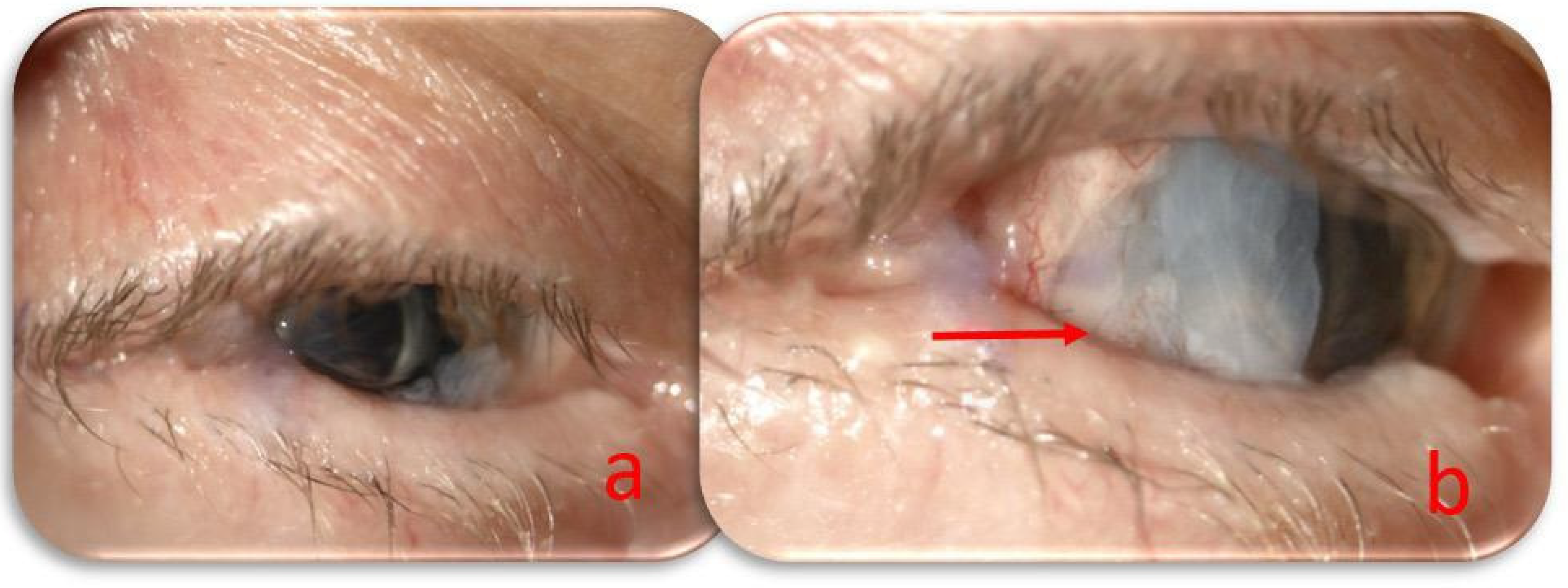

At the monthly follow-up, the lateral tarsorrhaphy was partially opened by removing the no-absorbable suture. The perforation area was still covered with an amniotic membrane and a conjunctival flap. The central cornea after HAM absorption appeared clear, the anterior chamber had regular depth, the iris was dysmorphic, the scleral fixed intraocular lens was correctly positioned, and the intraocular pressure was 14 mmHg. The visual acuity of counting fingers due to severe macular atrophy preexisting the corneal perforation (

Figure 3). The treatment regimen was modified with intensive ocular lubrication, and follow-up visits were scheduled every two weeks.

Unfortunately, our patient’s clinical conditions deteriorated rapidly probably due to progression of disease, culminating in his death.

4. Discussion

Cabozantinib is a drug belonging to the VEGFR-TKI family that proved to be effective in the treatment of various advanced-stage neoplasms. Multiple studies about Cabozantinib have reported a range of AEs—some very common, while others are relatively rare—largely similar to those observed with other VEGFR-TKIs. The most frequent ones include diarrhea, fatigue, hypertension, HFS, and hypothyroidism, whereas the less common ones include thromboembolic or hemorrhagic events that can lead to severe complications [

14]. Very few data in the literature concern VEGFR-TKIs-mediated ocular AEs, and these are limited to a handful of case reports describing bilateral optic disc edema, exudative retinal detachment, and choroiditis [

8,

9,

11]. No data have been published regarding corneal perforation during Cabozantinib therapy. To date, only one case of this AE has been reported in connection with another VEGFR-TKI, Regorafenib [

10]. Therefore, given the limited knowledge about such AEs, we deemed it necessary to describe another case of corneal perforation in a patient with advanced RCC who was undergoing treatment with Cabozantinib. Our patient received Cabozantinib after progression to Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib, according to the results of the METEOR trial [

5]. The patient started therapy at the dosage of 60 mg/die although it was necessary to apply some dose reductions because of some grade 2 AEs (according to CTCAE v6.0) such as asthenia, diarrhea, dysgeusia, and loss of appetite. However, after approximately 15 months of treatment, the patient began to experience pain and vision loss in the right eye. Thus, the diagnosis of corneal perforation, medical and surgical treatment were performed.

Based on the very limited data about ocular AEs on VEGFR-TKIs, there is no clear evidence to directly correlate corneal perforation to the treatment with Cabozantinib. However, several factors might contribute to explaining this correlation. First of all, similarly to the other VEGFR-TKIs, Cabozantinib leads to the block of neoangiogenesis through the inhibition of VEGFR2 [

11,

12,

13]. The result is the reduction of nutrients and oxygen supply to the tumor thereby slowing its growth. Moreover, this condition favors the occurrence of a hypoxic TME leading to a decrease in the release of cytokines and growth factors, rendering the microenvironment less favorable to tumor growth. On the other hand, it is well known that various growth factor receptors including VEGFR, FGFR, and PDGFR are expressed in normal ocular tissues such as corneal stroma, corneal epithelium, and conjunctival endothelium [

15]. The stimulation of these receptors by the correspondening growth factor favors vascular permeability and corneal cell proliferation enabling corneal homeostasis and recovery [

15]. Cabozantinib, through its different mechanisms of action, might undermine the ocular environment due to a lack or imbalance of growth factors in the tear film with a reduction of corneal epithelium proliferation. This condition might cause the occurrence of dry eye and the delay of corneal healing. Moreover, VEGFR is also expressed on corneal nerves so VEGF acts as an important neurotrophic growth factor [

5]. In this regard, the local administration of anti-VEGF therapy determined a reduction in corneal nerve fiber density, number of fibers, number of bifurcations, and total nerve fiber length [

16]. Therefore, this may lead to an increase in dry eye syndrome and even the onset of corneal ulcers. However, on the other hand, one study demonstrated the effectiveness of ocular therapy with anti-VEGF agents in blocking neovascularization, while also showing no ocular toxicity [

17].

Up to date, no reliable predictive factors for VEGFR-TKIs-mediated ocular toxicity have been defined. However, based on the limited data available in the literature, patients undergoing treatment with these drugs should be closely monitored to enable the early identification and management of potential ocular AEs. Management of corneal perforation should include the administration of topical antibiotics to prevent secondary infections, the employment of medications that promote corneal re-epithelialization, corneal tarsorrhaphy, and the suspension of VEGFR-TKI treatment until healing occurs. In cases of persistence or recurrence, permanent discontinuation of therapy should be considered.

5. Conclusions

Given the very limited data regarding ocular AEs under VEGFR-TKIs, we felt it was necessary to inform the scientific community of another case of corneal perforation in a patient affected by advanced RCC on therapy with a VEGFR-TKI, Cabozantinib.

Based on Cabozantinib mechanisms of action, it is possible to suppose a correlation with this side effect. Therefore, particular importance should be given to ophthalmologic surveillance during treatment with this type of therapy, in case of ocular symptoms.

Further studies are necessary to deepen knowledge about VEGFR-TKI-mediated ocular AEs, also through the development of scoring scales to assess the correlation between drugs and patients’ ocular symptoms.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cheng, K.; Liu, C.-F.; Rao, G.-W. Anti-Angiogenic Agents: A Review on Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) Inhibitors. Curr Med Chem 2021, 28, 2540–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veeravagu, A.; Hsu, A.; Cai, W.; Hou, L.; Tse, V.; Chen, X. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors as Anti-Angiogenic Agents in Cancer Therapy. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov 2008, 2, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Meyer, T.; Cheng, A.-L.; El-Khoueiry, A.B.; Rimassa, L.; Ryoo, B.-Y.; Cicin, I.; Merle, P.; Chen, Y.; Park, J.-W.; et al. Cabozantinib in Patients with Advanced and Progressing Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2018, 379, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlumberger, M.; Elisei, R.; Müller, S.; Schöffski, P.; Brose, M.; Shah, M.; Licitra, L.; Krajewska, J.; Kreissl, M.C.; Niederle, B.; et al. Overall Survival Analysis of EXAM, a Phase III Trial of Cabozantinib in Patients with Radiographically Progressive Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2017, 28, 2813–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Escudier, B.; Powles, T.; Tannir, N.M.; Mainwaring, P.N.; Rini, B.I.; Hammers, H.J.; Donskov, F.; Roth, B.J.; Peltola, K.; et al. Cabozantinib versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma (METEOR): Final Results from a Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol 2016, 17, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Hessel, C.; Halabi, S.; Sanford, B.; Michaelson, M.D.; Hahn, O.; Walsh, M.; Olencki, T.; Picus, J.; Small, E.J.; et al. Cabozantinib versus Sunitinib as Initial Therapy for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma of Intermediate or Poor Risk (Alliance A031203 CABOSUN Randomised Trial): Progression-Free Survival by Independent Review and Overall Survival Update. Eur J Cancer 2018, 94, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motzer, R.J.; Powles, T.; Burotto, M.; Escudier, B.; Bourlon, M.T.; Shah, A.Y.; Suárez, C.; Hamzaj, A.; Porta, C.; Hocking, C.M.; et al. Nivolumab plus Cabozantinib versus Sunitinib in First-Line Treatment for Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma (CheckMate 9ER): Long-Term Follow-up Results from an Open-Label, Randomised, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol 2022, 23, 888–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y. Te; Lin, C.J.; Tsai, Y.Y.; Hsia, N.Y. Bilateral Optic Disc Edema as a Possible Complication of Cabozantinib Use-a Case Report. Eur J Ophthalmol 2023, 33, NP56–NP59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephenson, K.A.J.; Mckay, B.R.; Paton, K.E. Cabozantinib-Associated Exudative Retinal Detachment and Choroiditis: A Case Report. J Curr Ophthalmol 2024, 36, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanfant, L.; Trone, M.C.; Garcin, T.; Gauthier, A.S.; Thuret, G.; Gain, P. [Corneal Perforation with Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Chemotherapy: REGORAFENIB]. J Fr Ophtalmol 2021, 44, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacy, S.A.; Miles, D.R.; Nguyen, L.T. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Cabozantinib. Clin Pharmacokinet 2017, 56, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grülich, C. Cabozantinib: A MET, RET, and VEGFR2 Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor. Recent Results Cancer Res 2014, 201, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakes, F.M.; Chen, J.; Tan, J.; Yamaguchi, K.; Shi, Y.; Yu, P.; Qian, F.; Chu, F.; Bentzien, F.; Cancilla, B.; et al. Cabozantinib (XL184), a Novel MET and VEGFR2 Inhibitor, Simultaneously Suppresses Metastasis, Angiogenesis, and Tumor Growth. Mol Cancer Ther 2011, 10, 2298–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlBarakat, M.M.; Ahmed, Y.B.; Alshwayyat, S.; Ellaithy, A.; Y. Al-Shammari, Y.; Soliman, Y.; Rezq, H.; Abdelazeem, B.; Kunadi, A. The Efficacy and Safety of Cabozantinib in Patients with Metastatic or Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2024, 37, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ljubimov, A. V.; Saghizadeh, M. Progress in Corneal Wound Healing. Prog Retin Eye Res 2015, 49, 17–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldhardt, R.; Batawi, H.I.M.; Rosenblatt, M.; Lollett, I. V.; Park, J.J.; Galor, A. Effect of Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Therapy on Corneal Nerves. Cornea 2019, 38, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Jiang, Q.; Yao, J. A Small Molecular Multi-Targeting Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor, Anlotinib, Inhibits Pathological Ocular Neovascularization. Biomed Pharmacother 2021, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).