1. Introduction

Treatment with targeted anticancer agents (TAAs) improves survival and quality of life of patients with various cancer types. Unlike chemotherapy (ChT), TAAs specifically interfere with different molecular pathways involved in the growth and progression of malignant cells and are generally considered to be less toxic than ChT [

1]. Precise targeting of some approved TAAs can be achieved through the identification of biomarkers, which can be detected using in vitro companion diagnostic tests for biomarkers (hereafter CDx) [

2]. However, patients treated with TAAs may experience a spectrum of toxicities, unique to this class of agents, with safety profile differences between small molecules (SMs) and monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) [

3]. Moreover, previous research has shown that TAAs without a specific molecular target are more toxic than those with a specific target identified with a CDx [

4].

Despite rigorous documentation of adverse events, some serious drug-related toxicities (i.e., adverse drug reactions [ADRs]) of TAAs may remain unrecognized during clinical trials but become evident only when these TAAs are used in everyday clinical practice [

5]. The main reasons may be the relatively small number of patients who participate in pivotal clinical trials and very restrictive eligibility criteria for their participation [

6]. Furthermore, symptomatic ADRs which are experienced by patients cannot be assessed reliably by investigators and may be under-reported within clinical trials [

7]. Throughout the post-marketing phase, regulatory agencies meticulously compile safety data on approved anticancer agents from diverse sources, including ongoing clinical trials, spontaneous reporting, phase IV trials, and surveillance programs [

8,

9]. Previous research showed that 49% and 55% of serious and potentially fatal ADRs of TAAs, respectively, reported in updated drug labels during the first few years after their regulatory approval, were not described in initial drug labels at the time of their approval [

10]. A long-term trajectory of the emerging new serious ADRs in updated drug labels of TAAs and possible predictors for their emergence are currently not known.

Here we hypothesized that new serious and potentially fatal ADRs continue to emerge in updated drug labels of TAAs several years after their initial approval. We also investigated potential predictors for the emergence of new ADRs in updated drug labels of TAAs, including drug type and the availability of a CDx.

2. Methods

2.1. Identification of TAAs and Analysis of ADRs

In August 2023, we identified all TAAs approved for the treatment of solid cancers and hematological malignancies by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) before July 2013, ensuring that each eligible TAA had been on the market for at least 10 years. Initial and all updated drug labels of eligible TAAs were retrieved from the FDA Drug Approvals and Databases website [

11]. Drug labels of approved TAAs were consulted for serious ADRs in the Warnings & Precautions (W&Ps) and for potentially fatal ADRs in the Boxed Warnings (BWs) section of their drug labels, excluding embryo-fetal toxicity. ADRs reported in the W&Ps and BWs sections are considered serious and clinically significant, with a clear causal link to the drug. BWs highlight fatal, life-threatening, and permanently disabling adverse reactions, urging clinicians to carefully monitor and weigh the risks and benefits of the drug [

12].

2.2. Outcomes of Interest

The primary outcome of interest was a long-term trajectory of emerging new serious and potentially fatal ADRs in updated drug labels of TAAs. A late ADR was defined as any new W&P or BW that first appeared in an updated drug label ≥ 5 years after the initial approval of the corresponding TAA. We also investigated potential predictors for the emergence of new ADRs in updated drug labels such as type of TAA (SM vs. mAb) and availability of a CDx (yes vs. no). The availability of a CDx in this study was defined as the use of CDx for all approved indications of a particular TAA.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. The Mann-Whitney test was used for comparisons of the number of ADRs (i.e., W&Ps and BWs) concerning the type of the TAA and availability of a CDx. To study a time trajectory of emerging new ADRs in updated drug labels concerning other variables, a generalized linear mixed model was used [

13]. Since the outcome was a count (the number of ADRs over time) a negative binomial inverse link function was used which accounts for overdispersion. The effect of time was non-linear thus its quadratic component was added in the models. While drug type (SM vs. mAb) and availability of a CDx (yes vs. no) were added as fixed effects, the TAA was added as a random effect into the model. The models also allowed for a random effect in the slope for time and time squared. Independence for intercept and slope coefficients for time and time squared was incorporated. An inclusion of interactions between covariates was not necessary in a final model. Additionally, sensitivity analyses were conducted, in which the availability of a CDx was defined as the use of a CDx for at least one indication of particular TAAs.

The analysis was performed using the R programming language version 4.3.1. P-values of < 0.05 were deemed statistically significant. No adjustments for multiple comparisons were made.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Eligible Targeted Anticancer Agents

We identified 38 TAAs approved by the FDA between 1997 and 2013. One drug, tositumomab, was withdrawn from the market for commercial reasons in October 2013, and its labels were not available on the FDA website. Therefore, 37 TAAs were eligible for the analysis. Characteristics of eligible TAAs are presented in the Supplementary

Table 1. Of these, 25 (68%) were SMs and 11 (30%) had an available CDx (i.e., drug labels recommended use of a CDx for all approved indications). Drug labels of 4 (11%) TAAs recommended the use of a CDx for at least one but not all approved indications. Nineteen (51%) TAAs were approved before the year 2011. Overall, a median time from the regulatory approval to the last updated drug label was 11.8 years (IQR: [10.0-15.0]).

3.2. Reporting of Warnings and Precautions

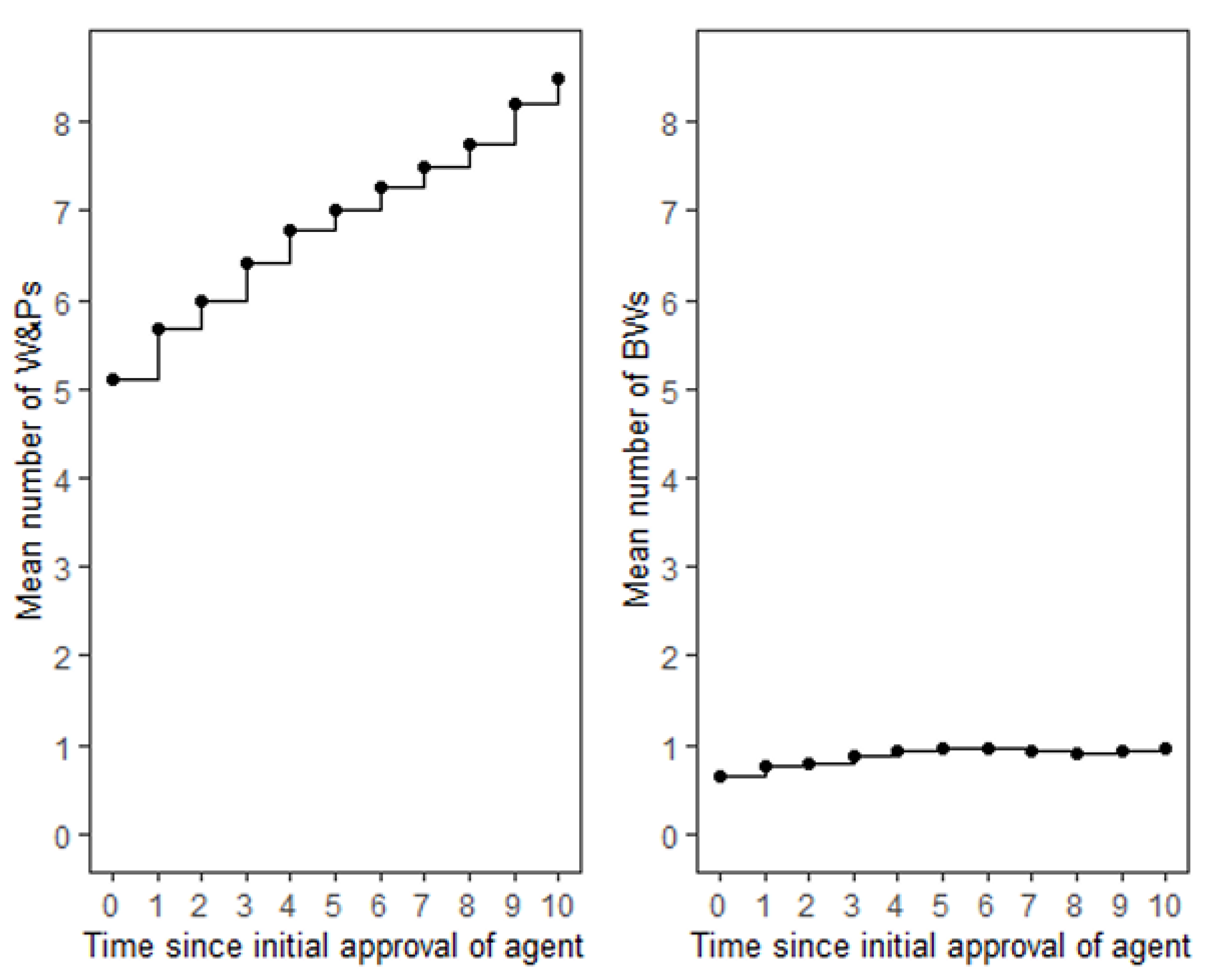

The mean number of W&Ps reported in the initial drug labels of TAAs was 5.1. Over time, there was a consistent increase in the number of W&Ps for most agents reaching a mean number of W&Ps of 8.5 at 10 years (

Figure 1). Only two agents, ziv-aflibercept and pertuzumab, maintained a constant number of W&Ps throughout this period (Supplementary

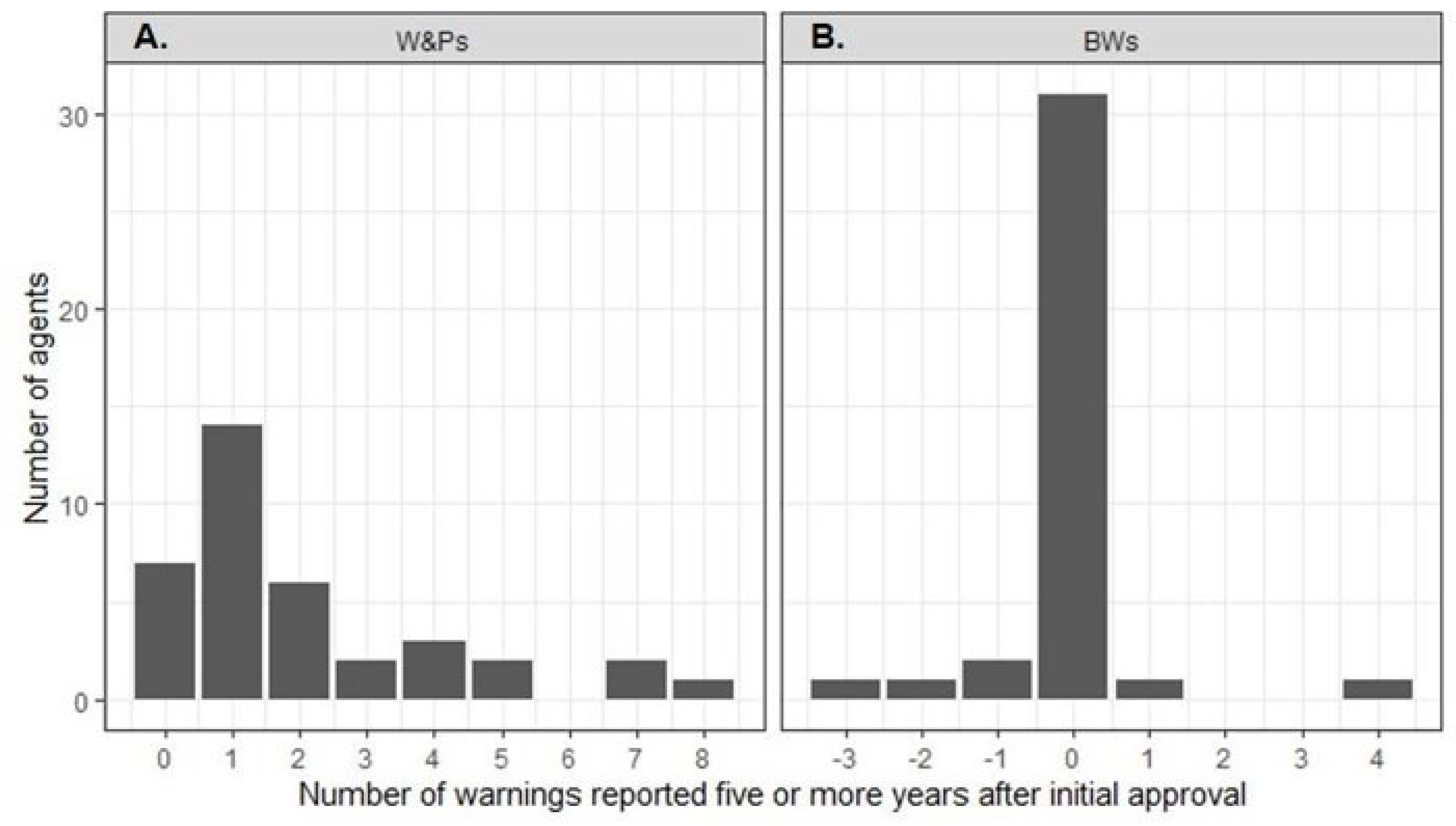

Figure 1). At least one late W&P was reported for 30 (81%) TAAs (

Figure 2A). The highest number of new late W&Ps was reported for rituximab, imatinib mesylate, and sunitinib malate. In contrast, no new late W&Ps were reported for erlotinib hydrochloride, ofatumumab, pertuzumab, ziv-aflibercept, regorafenib, ponatinib hydrochloride, and ado-trastuzumab emtansine (Supplementary

Figure 1). For 9 (24%) TAAs new W&Ps emerged more than 10 years after their initial regulatory approval (Supplementary

Figure 1). There were significantly fewer new late W&Ps reported for mAbs compared to SMs (1.3 vs. 2.4; p = 0.03). Although there were fewer new late W&Ps for agents with an available CDx as compared to those without, the difference was not statistically significant (availability of a CDx yes vs. no: 1.4 vs. 2.4; p = 0.19). Sensitivity analysis did not change these results.

Results of the generalized linear mixed model for W&Ps are presented in

Table 1. While time was a significant predictor for the increasing number of new W&Ps (coef. for Time = 0.06; p ˂ 0.001), the rate of appearance of new W&Ps significantly decreased over time (coef. for Time

2 = - 0.002; p = 0.001). Updated drug labels of SMs received significantly more new W&Ps as compared to mABs over time (coef. for SMs = 0.35; p-value = 0.04) The number of W&Ps was smaller for TAAs with available CDx as compared to those without available CDx, although this difference was not statistically significant (coef. for CDx yes = - 0.15; p-value = 0.44). A sensitivity analysis did not change our results (

Supplementary Table S2).

3.3. Reporting of Boxed Warnings

The overall number of BWs was substantially lower as compared to W&Ps, with a mean of 0.65 BWs reported in initial drug labels at the time of regulatory approval of TAAs. Over time, the increase in BWs was modest, reaching a mean of 0.97 ADRs at 10 years (

Figure 1). Notably, 23 (62%) TAAs maintained a constant number of BWs throughout the entire period, and for 17 (46%) TAAs the number of BWs remained zero. While an increase in the number of BWs was observed for 10 (27%) TAAs, a decrease in the number of BWs occurred for 4 (11%) agents - bevacizumab, cabozantinib s-malate, panitumumab, and ipilimumab (Supplementary

Figure 2). At least one late new BW was reported in drug labels of only 2 (5%) agents, rituximab and ibritumomab tiuxetan. For 31 (84%) TAAs, the number of BWs remained unchanged after five years (

Figure 2B). The number of late BWs did not differ between drug types (p=0.77) or depend on the availability of a CDx (p = 0.76).

Results of the generalized linear mixed model for BWs are presented in

Table 2. Similar to the W&Ps, time was a significant predictor of an increasing number of new BWs (coef. for Time = 0.07; p=0.008) but the rate of appearance of new BWs decreased over time (coef. for Time

2 = - 0.05; p = 0.01). Updated drug labels of TAAs classified as SMs received a significantly smaller number of BWs as compared to mAbs over time (coef. for SMs = - 3.11; p < 0.001). Similar to the analysis of W&Ps, there were no statistically significant differences in the number of BWs in regard to the availability of a CDx (coef. for CDx = 0.22; p = 0.77). These results did not differ in the sensitivity analysis (

Supplementary Table S3).

4. Discussion

The process of drug licensing and regulatory approval of new anticancer agents involves a careful balancing of benefits against risks. For various reasons, information on the safety of new anticancer agents is often limited at the time of their regulatory approval [

6,

10]. Results of our study showed that new serious and potentially fatal ADRs continue to emerge in updated drug labels of TAAs several years after their initial approval: for 81% and 5% of the TAAs, new W&Ps and BWs emerged five or more years after regulatory approval, respectively. However, the rate of appearance of new ADRs decreased over time. As compared to mAbs, drug labels of SMs are more likely to receive new serious W&Ps.

After initial regulatory approval TAAs often receive several additional, supplemental indications leading to their use in a broader population of patients with different types of cancer. Supplemental indications accounted for 75% of new oncology approvals in 2018 [

14]. In a cohort of cancer agents approved by both the FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), manufacturers added supplemental indications at a higher rate in the US as compared to the EU despite starting with nearly identical numbers of indications at the time of initial approval [

15]. A study of first and supplemental indications of drugs approved by the FDA and the EMA among which the largest subset were anticancer agents showed that a proportion of supplemental indications rated as having a high therapeutic value was substantially lower than for first indications [

16]. One of the possible factors contributing to a lower therapeutic value of the supplemental indications might be new ADRs which are not known at the time of initial drug approval but become evident later when these anticancer agents are being evaluated in a broader population of patients with cancer.

A safety assessment within single-arm trials (usually with smaller sample sizes and shorter follow-up than pivotal randomized clinical trials) may be unreliable as symptoms of advanced cancer can mimic and obscure ADRs [

17]. Roughly 60% of new TAA indications between 2012 and 2021 were based on results of the early-phase clinical trials, with annual approval rates based on them rising by 22.2% (vs. 5% from randomized clinical trials) [

18]. This may result in a potentially unreliable assessment of the benefit-risk profiles at the approval of new indications and new ADRs may emerge only when these agents are used in randomized clinical trials and/or everyday clinical practice. Furthermore, long-term and sequential use of various TAAs within and/or outside of clinical trials may also be associated with an increased risk for the development of new serious ADRs, especially in the metastatic setting, where TAAs are often administered for several months or years, sometimes even beyond disease progression [

19,

20]. Prolonged exposure to TAAs may reveal previously undetected ADRs as the buildup of toxic substances in the body increases the likelihood of ADRs [

21]. Design of the registrational clinical trials and prolonged use of the TAAs may be important factors for the emergence of new serious ADRs after their regulatory approval.

Our findings showed that SMs have a higher likelihood of receiving new serious W&Ps as compared to mAbs. Both mAbs and SMs can exhibit on-target and off-target effects due to their interaction with common signaling pathways in cancer and normal cells. It is well known that a toxic potential of the SMs correlates positively with the number of inhibited kinases and that the off-target effects may increase the likelihood of the ADRs [

22,

23,

24,

25]. In contrast to the SMs, mAbs exhibit greater selectivity and affinity for their targets, contributing to a lower incidence of new ADRs [

26]. Moreover, while mAbs are administered parenterally, the oral administration of SMs leads to greater inter-individual variability of the plasma concentrations and possible overexposure to SMs at a given dose [

27]. Plasma concentrations of SMs can also be influenced by environmental and genetic factors due to their reliance on cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme metabolism and other pharmacokinetic processes [

28,

29]. Consequently, interactions with other drugs, which are commonly used in patients in everyday clinical practice can significantly alter the exposure to SMs [

30]. In contrast, mAbs avoid CYP metabolism, resulting in fewer interactions and potentially lower toxicity. In our study, the availability of a CDx did not predict the emergence of serious and potentially fatal ADRs. Results of the meta-analysis evaluating the impact of CDx on the efficacy and safety of TAAs corroborate our findings as the availability of the CDx did not significantly affect the rate of toxic deaths; however, it reduced the odds for treatment discontinuation and grade 3-4 adverse events in this meta-analysis [

31]. In summary, off-target effects of TAAs, variability in their metabolism due to genetic factors, and drug-drug interactions may all be important factors responsible for the development of new serious ADRs when these agents are used in everyday clinical practice. Future research should be focused on the pharmacogenetics and dose-finding studies which might lead to a more predictable safety of newly approved TAAs, especially of the SMs.

Our study has several limitations. First, a small number of TAAs might impact the robustness of our statistical findings, especially findings about the impact of a CDx on the emergence of new ADRs. Secondly, some other factors such as type of cancer (solid cancers vs. hematological malignancies), the number of approved indications reflecting the prevalence of use of a particular TAA in the cancer population, and type of the mAB (e.g., mouse vs. humanized mAb) might give us some further granularity of the data. However, the inclusion of additional variables in our study would decrease the robustness of our statistical analysis. Thirdly, since the availability of a CDx was defined as its use for all approved indications of a particular TAA, an alternative definition of the availability of a CDx might lead to different conclusions. However, a sensitivity analysis in which the availability of a CDx was defined as the use of CDx for at least one approved indication of a particular TAA led to the same results. Finally, these findings might not fully apply to the emerging new classes of anticancer drugs (e.g., antibody-drug conjugates, immune checkpoint inhibitors, bispecific antibodies) which were underrepresented in our dataset. Due to their very small number these new anticancer agents were grouped and analyzed together with other mABs in our analysis.

5. Conclusions

While TAAs offer substantial therapeutic benefits to patients with various cancers, they are associated with safety concerns that require continuous scrutiny. The oncological community, regulatory bodies, and payers should be aware of the continuously evolving benefit-risk ratio of approved TAAs. More rigorous evaluation of TAAs within clinical trials and in the real-world setting might lead to their more predictable safety profiles.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S., D.M. and B.Š.; Methodology, D.S., D.M., D.R. and B.Š.; Software, D.S. and D.M.; Validation, D.S and B.Š.; Formal Analysis, D.S., D.M., D.R. and B.Š.; Investigation, D.S. and B.Š.; Resources, B.Š.; Data Curation, D.S. and B.Š.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, D.S., D.M., D.R. and B.Š.; Writing – Review & Editing, D.S., D.M., D.R. and B.Š.; Visualization, D.S., D.M., D.R. and B.Š.; Supervision, B.Š.; Project Administration, B.Š; Funding Acquisition, D.M. and B.Š.

Funding

This work was supported by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (ARIS) (grant numbers P3-0154, P3-0321 and a research project number Z3-50124).

Data availability statement

Acknowledgments

The funder did not play a role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

List of contributors

Authors thank to Prof. Ian Tannock, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Toronto, Canada for his very useful comments during the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- Min HY, Lee HY. Molecular targeted therapy for anticancer treatment. Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 2022;54(10):1670-1694.

- US Department of Health and Human Services: In vitro companion diagnostics devices: guidance for industry and food and drug administration staff. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-informa.on/search-fda-guidance-documents/invitro-companion-diagnos.c-devices (accessed on 10th January 2025).

- Basak D, Arrighi S, Darwiche Y, Deb S. Comparison of Anticancer Drug Toxicities: Paradigm Shift in Adverse Effect Profile. Life. 2021;12(1):48.

- Niraula S, Amir E, Vera-Badillo F, Seruga B, Ocana A, Tannock IF. Risk of Incremental Toxicities and Associated Costs of New Anticancer Drugs: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(32):3634-3642.

- Assoun S, Lemiale V, Azoulay E. Molecular targeted therapy-related life-threatening toxicity in patients with malignancies. A systematic review of published cases. Intensive Care Medicine. 2019;45(7):988-997.

- Srikanthan A, Vera-Badillo F, Ethier J, et al. Evolution in the eligibility criteria of randomized controlled trials for systemic cancer therapies. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2016;43:67-73.

- Seruga B, Templeton AJ, Badillo FEV, Ocana A, Amir E, Tannock IF. Under-reporting of harm in clinical trials. The Lancet Oncology. 2016;17(5):e209-e219.

- Baldo P, De Paoli P. Pharmacovigilance in oncology: evaluation of current practice and future perspectives. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2014;20(5):559-569.

- Food and Drug Administration: MedWatch: The FDA Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch-fda-safety-information-and-adverse-event-reporting-program (accessed on 10th January 2025).

- Seruga B, Sterling L, Wang L, Tannock IF. Reporting of Serious Adverse Drug Reactions of Targeted Anticancer Agents in Pivotal Phase III Clinical Trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(2):174-185.

- Food And Drug Administration: Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm (accessed on 10th January 2025).

- Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research and Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research: Warnings and Precautions, Contraindications, and Boxed Warning Sections of Labeling for Human Prescription Drug and Biological Products — Content and Format. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/warnings-and-precautions-contraindications-and-boxed-warning-sections-labeling-human-prescription (accessed on 10th January 2025).

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software. 2015;67(1).

- IQVIA - Global Oncology Trends 2018. Available online: https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports-and-publications/reports/global-oncology-trends-2018 (accessed on 10th January 2025).

- Stoelinga J, Bloem LT, Russo M, Kesselheim AS, Feldman WB. Comparing supplemental indications for cancer drugs approved in the US and EU. European Journal of Cancer. 2024;212:114330.

- Kerstin Noëlle Vokinger, Glaus CEG, Kesselheim AS, Serra-Burriel M, Ross JS, Hwang TJ. Therapeutic value of first versus supplemental indications of drugs in US and Europe (2011-20): retrospective cohort study. Published online July 5, 2023:e074166-e074166.

- Pignatti F, Jonsson B, Blumenthal G, Justice R. Assessment of benefits and risks in development of targeted therapies for cancer - The view of regulatory authorities. Molecular Oncology. 2014;9(5):1034-1041.

- Huang Y, Xiong W, Zhao JW, Li W, Ma L, Wu H. Early phase clinical trial played a critical role in the Food and Drug Administration–approved indications for targeted anticancer drugs: a cross-sectional study from 2012 to 2021. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2023;157:74-82.

- Kuo WK, Weng CF, Lien YJ. Treatment beyond progression in non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Oncology. 2022;12.

- Serra F, Faverio C, Lasagna A, et al. Treatment beyond progression and locoregional approaches in selected patients with BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma. Drugs in Context. 2021;10:1-6.

- Kirkali Z. Adverse events from targeted therapies in advanced renal cell carcinoma: the impact on long-term use. BJU International. 2011;107(11):1722-1732.

- Lin A, Giuliano CJ, Palladino A, et al. Off-target toxicity is a common mechanism of action of cancer drugs undergoing clinical trials. Science translational medicine. 2019;11(509).

- Steegmann JL, Cervantes F, le Coutre P, Porkka K, Saglio G. Off-target effects of BCR–ABL1 inhibitors and their potential long-term implications in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia & Lymphoma. 2012;53(12):2351-2361.

- Benn CL, Dawson LA. Clinically Precedented Protein Kinases: Rationale for Their Use in Neurodegenerative Disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2020;12.

- Imai K, Takaoka A. Comparing antibody and small-molecule therapies for cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2006;6(9):714-727.

- Castelli MS, McGonigle P, Hornby PJ. The pharmacology and therapeutic applications of monoclonal antibodies. Pharmacology Research & Perspectives. 2019;7(6).

- Calvo E, Walko C, Dees EC, Valenzuela B. Pharmacogenomics, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacodynamics in the Era of Targeted Therapies. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. 2016;35:e175-184.

- Gharwan H, Groninger H. Kinase inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies in oncology: clinical implications. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2016;13(4):209-227.

- Mueller-Schoell A, Groenland SL, Scherf-Clavel O, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of oral targeted antineoplastic drugs. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2021;77(4):441-464.

- Mikus G, Foerster KI. Role of CYP3A4 in kinase inhibitor metabolism and assessment of CYP3A4 activity. Translational Cancer Research. 2017;6(S10):S1592-S1599.

- Ocana A, Ethier JL, Díez-González L, et al. Influence of companion diagnostics on efficacy and safety of targeted anti-cancer drugs: systematic review and meta-analyses. Oncotarget. 2015;6(37):39538-39549.\.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).