Introduction

Interest in Halting IgA Nephropathy Progression

IgA nephropathy (IgAN), defined by the presence of glomerular deposits of IgA dominant or co-dominant over the other classes of immunoglobulins, is a rare disease but a common glomerulonephritis [

1,

2]. For the first decades after its identification IgAN was considered a benign condition, because IgA immunoglobulins are not pro-inflammatory as IgG [

3] and the clinical presentation of these subjects is generally mild, with microscopic hematuria and moderate proteinuria or rapidly vanishing gross haematuria. The interest in diagnosing and treating IgAN has increased over the last decades, as the perception of IgAN as a progressive kidney disease became recognizable over long-term follow-ups [

4,

5]. In adults with IgAN, 20–40% of any cohort develop end stage kidney disease (ESKD) with need of renal replacement therapy within 10–20 years after diagnosis [

6]. Patients who do not progress to ESKD over their life have a loss of annual eGFR in median of 1.2-3.5 ml/min/year as detected in an international cohort of almost 4,000 patients followed since kidney biopsy [

7]. In recent registry data from UK enrolling incident and prevalent patients with proteinuria >0.5 g/day or eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m

2, a progression to ESKD was found in 50% of adults and 20% of children [

8]. Almost all patients were at risk of progression to kidney failure within their expected lifetime if eGFR loss was >1 ml/min/1.73 m2. Children are also at risk of progression due to their life expectancy even if their post-biopsy eGFR profiles show a trajectory with initial improvement 1-2 years after biopsy, followed by a stabilization and a subsequent decline in eGFR like what observed in adults [

9]. Moreover, IgAN can recur in grafted kidney, leading to transplanted kidney failure and return to dialysis [

10]. Therefore, a strategy is needed to attempt to halt or further slow the relentless progression of IgAN.

Pathogenesis of IgAN: the Initiating Events and the Progression

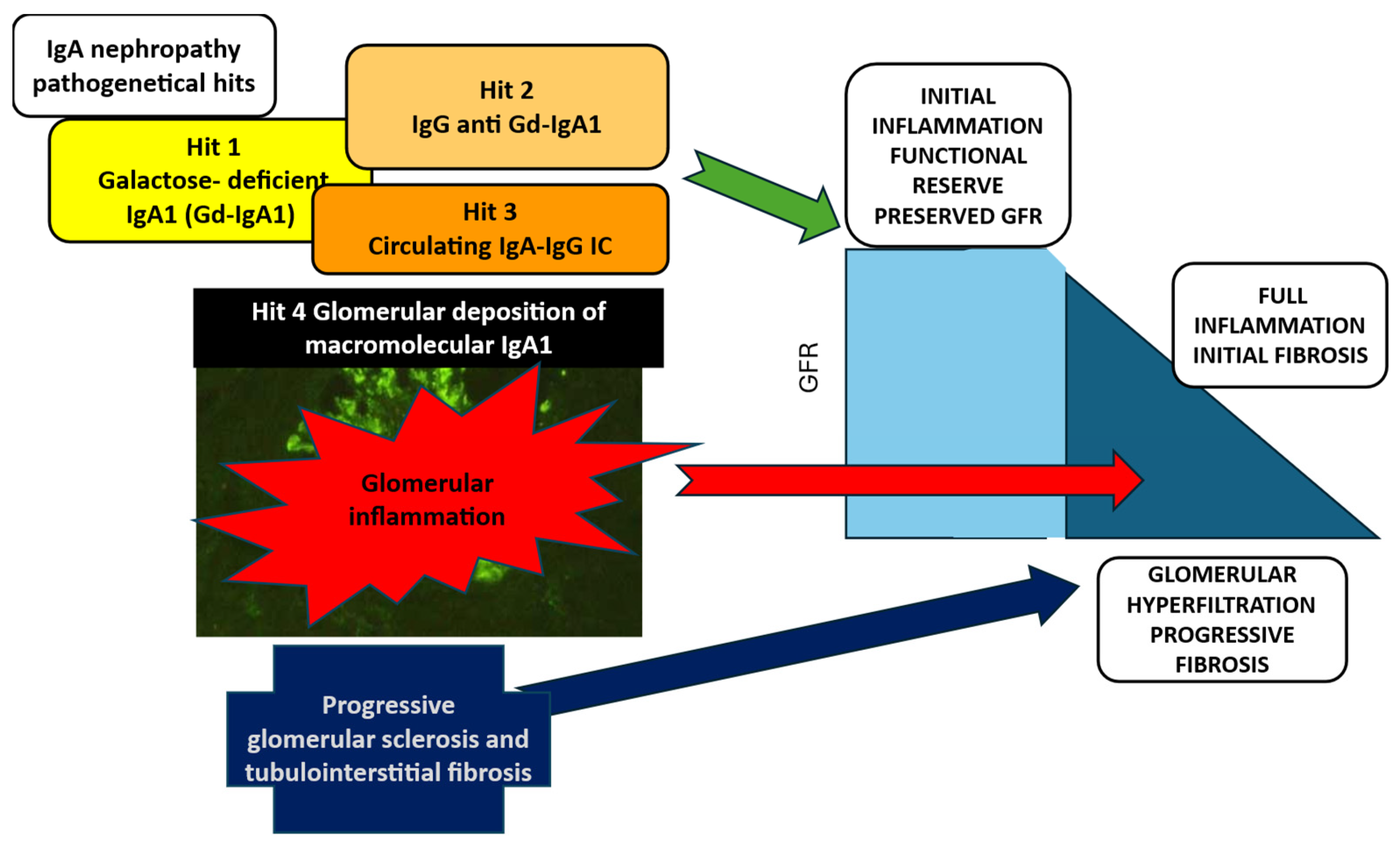

IgAN is an inflammatory glomerular disease, in which four pathogenetical hits can be identified (

Figure 1) [

11]. The initiating event is the production galactose-deficient IgA1 (Gd-IgA1) (hit 1) which induces the formation of auto-antibodies anti-Gd-IgA1 (hit 2) resulting in circulating IgA immune complexes (IgAIC) (hit 3). The glomerular inflammatory reaction induced by the deposition of IgAIC triggers mesangial cell proliferation, release of cytokines and activation of the complement system, leading to full development of IgAN lesions (hit 4). In this phase the kidney functional reserve is activated and compensates for the early loss of glomerular function, but the chronic process activates glomerular sclerosis and tubule-interstitial damage, with glomerular hyperfiltration and the chronic kidney disease terminal common pathways ending in and progressive loss of kidney function. Persisting proteinuria and interstitial damage drive the chronic irreversible disease progression [

12]. Hence in the natural history of IgAN the initiating phlogistic event is shortly followed by the activation of the pro-sclerotic mechanisms, resulting in a mixed unique process which includes active damage as well as consequences of chronic damage, in a balance that changes over time toward the final prevalence of irreversible lesions.

An Overview of the Evolving Recommendations for Treating IgAN

The global vision of the recommended treatment for IgAN has undergone radical changes in recent decades, starting from enthusiastic results of some early RCTs with glucocorticosteroids (CS) [

13,

14,

15], followed by an unexpected braking from studies showing CS limited long-term benefits and/or safety concerns when using CS high doses or in association with other immunosuppressive drugs [

16,

17].This led to severe restriction of CS use as first approach to treatment of IgAN which was recommended to be mostly focused on optimized supportive care (SOC) with renin-angiotensin inhibition (RASB) and lifestyle modifications [

18]. This scenario was changed again by the new data on reduced CS dose [

19] and the results of a new steroid acting on the intestinal mucosa immune system [

20,

21]. Meanwhile new drugs targeting specific pathogenetic mechanisms operating at the initial phlogistic phase as well as during chronicity are being considered and the field is indeed at an evolving point with a complex road ahead [

22].

The First Treatment Approach to IgAN: Systemic Corticosteroids as the Most Powerful and Easily Available Broad-Acting Immunosuppressor

Glucocorticosteroids have been the milestone of treatment of IgAN over decades. In the 80s three RCTs showed clear evidence of benefits of CS treatment in reducing proteinuria and progression with loss of renal function [

13,

14,

15].The results were obtained with 6-months CS regimens, using either a course of 3 i.v. pulses of 1 g methylprednisolone and oral prednisone 0.5 mg/Kg on alternate days [

13], or a regimen of oral prednisone 0.8-1 mg/Kg/day for 2 months, weaning over 6 months [

14,

15]. Both protocols induced reduction in disease progression and proteinuria without serious side effects. A long-term legacy effect was observed for the i.v. protocol [

23]. These RCTs were performed without complete RASB since this treatment was not routinely used. Based on these studies, the 2012 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome (KDIGO) clinical guidelines [

24] suggested to give CS to patients with IgAN and good kidney function (GFR >50 mL/min/1.73 m

2) maintaining persistent proteinuria >1 g/day, despite 3-6 months of optimized supportive care with RASB.

Two RCTs performed in the last decade took care of an optimized supportive care (SOC), the STOP-IgAN [

16] and the Therapeutic evaluation of Steroids in IgA nephropathy (TESTING) study [

17]. In the STOP-IgAN trial two corticosteroid-immunosuppressive (CS/IS) regimens were adopted for 3 years (in case of eGFR> 60 ml/min: methylprednisolone pulse protocol, in case of eGFR <60 mL/min oral prednisone and cyclophosphamide/ azathioprine), and full SOC was adopted for treated and placebo subjects, with rigorous RASB and lifestyle changes. Patients in the methylprednisolone pulse arm more frequently than in SOC reached complete proteinuria remission (<0.3 g/day), but without effects on eGFR decline. The safety surveillance reported a high frequency of adverse events in both CS/IS and SOC (36% of patients) arms. A few severe adverse events (SAE) - obesity and impaired glucose tolerance - were significantly more frequent in the treatment group. The frequency of infections was similar in the CS/IS and SUP group, but there was one death due to Pneumocystis sepsis in the treatment group. Notably, SAE were more frequent in patients with reduced eGFR and treated with CS associated with immunosuppressive drugs. In a follow-up observation ten years later no protection from a 40% decline in eGFR or ESKD was reported [

25]. In the TESTING trial full doses of oral CS were adopted (0.6-0.8 mg/kg/day of methylprednisolone at reducing doses over 6-9 months) versus RASB 17].The RCT was discontinued during recruitment because of excess serious adverse events (mostly infections, including two deaths) in patients treated with CS.

Based on these RCTs, KDIGO 2021 concluded on the uncertainty over the safety and efficacy of CS treatment for IgAN and suggested focusing mostly on strenuous SOC including low sodium diet and maximally tolerated doses of RASB for 3-6 months before discussing risk and benefits of CS with patients who remain at risk for progression with persistent proteinuria >1 g/day despite SOC[

26].

Shortly after publication of KDIGO 2021, the breakthrough publication of the final TESTING RCT [

19] changed again the perspective of systemic CS treatment. In this study methylprednisolone dose was reduced from 0.6-0.8 mg/Kg/day for 2 months, tapering over 6-8 months to 0.4 mg/Kg/day for 2 months and the prophylaxis for Pneumocystis Jirovecii was added for 3 months. The study involved 257 CS treated patients (140 with full doses and 117 with low doses) and 246 patients on SOC with careful RASB use. After 4.6 years a significant effect on the primary end point (40% reduction GFR or ESKD) was observed in 28.8% of patients in CS group compared with 43.1% in the SOC group (P <0.001) and low doses were found to be as effective as full doses. SAE were reported in 10.9 % of patients treated with CS and in 2.8% iof those in SOC. Patients on reduced doses had less frequently SAE, but severe infections were reported in 3 cases, anyway of lower frequency than in the full dose protocol, reporting infections in 17 cases (3 fatal). Hence the enthusiasm on the efficacy of methylprednisolone treatment in IgAN with persistent proteinuria despite careful RASB, was tempered by the warning of side effects, particularly infections. It is to be mentioned that no attention has been regularly paid to CS toxicity prevention including a single morning dose or an alternate-day schedule and prescribing hypocaloric and low-sodium diet, vitamin D supplements and physical activity [

27].

A New Horizon for Corticosteroid Treatment in IgAN

The recent research has provided an innovative approach to CS therapy in IgAN, based on a formulation of Budesonide (Nefecon) designed to target the gut associated lymphoid tissue at the Peyer’s patches, major site of production of Gd-IgA1 located most abundantly at the distal jejunal site. Budesonide is a powerful CS with a formula which favours high local activity [

27,

28] and has a high hepatic clearance theoretically limiting systemic exposure.

The NefIgArd RCT [

20,

21] investigated 364 patients with IgAN and proteinuria >0.8 g/g or >1g/24h randomized to Nefecon 16 mg for 9 months or SOC. SOC continued in every patient over 2 years. After 9 months of RCT Nefecon a 27% reduction in proteinuria (urinary protein to creatinine ratio, UPCR) was observed (P<0.0003 versus placebo), and eGFR was more preserved (difference versus placebo 3.87 ml/min/1.73 m

2, P=0.0014). The eGFR benefit observed at 9 months was maintained for 15 months without treatment

. Time-weighted average eGFR loss was -2.5 ml/min/1.73 m

2/year in Nefecon-treated patients versus -7.5 ml/min/1.73 m

2/year in those in SOC (p< 0.0001) with a gain in the total slope of 2.9 ml/min/1.73 m

2/year (p<0.0001) in favor of Nefecon. The effects on eGFR decline were independent of baseline UPCR. A median 30% reduction in UPCR was detected after 9 months of treatment, when SOC only was given, with a further reduction at 12 months, of 47% compared to placebo. A reduction in UPCR of around 40% compared to placebo was observed till the end of the second year. At final observation, dipstick was negative for microscopic hematuria in 59% of patients treated with Nefecon compared to 39% of subjects in placebo.

During the 9 months of treatment TEAs were reported in 10% in the Nefecon group versus 5% in SOC. TAEs leading to drug discontinuation were reported in 9% of patients in Nefecon and 2% in placebo. The Nefecon group had hypertension (17%), peripheral edema (12%), muscle spasms (12%) and acne (11%), suggesting a partial systemic exposure to the active drug. SAEs related to infection were reported in 3% of patients treated with Nefecon and in 1% of those with SOC. In 2023 the FDA approved budesonide delayed release capsules to reduce the loss of kidney function in adults with primary IgAN at risk for disease progression.

Some observations can be of interest when considering in parallel the results of the two RCTs which used an intestinal targeted release formulation of budesonide, Nefecon for 9 months (NefIgArd RCT) or systemic methylprednisone for 6-9 months (TESTING RCT) [

22].

Patients’ demographic data differed for ethnicity (76% White in NefIgArd versus 76% Chinese in TESTING), however the median values at baseline of proteinuria and GFR were surprisingly very similar (proteinuria: 2.7 ±1.7 g/24 h and eGFR 56.1 (45-70) ml/min/1.73m2 in 182 patients treated with Nefecon; proteinuria: 2.55 ±2.45 g/24 and eGFR 56.1 (43-75) ml/min/1.73m2 in 136 patients then treated with methylprednisolone for 6-9 months.) The effect of methylprednisolone was observed after 3-6 months, while Nefecon showed significant effect after 9 months, however the antiproteinuric effect was similar with 40-50% of proteinuria reduction lasting over 1-2 years. Nefecon and methylprednisone showed in the two RCTs an increase in GFR at 3-6 months and a subsequent GFR decline over 2 years. Patients in Nefecon had a loss in GFR of -6 ml/min//1.73m2 while SOC had -12 ml/min/1.73m2 over 2 years of follow-up. Patients on Methylprednisolone had a GFR loss of - 2. 5 ml/min/1.73m2/year while SOC arm had a loss of - 4.9 ml/min/1.73m2/year over 3.5 years in median follow-up.

New KDIGO to Be Published in 2025

In the years following the publication of KDIGO 2021 several studies indicated that the concept of approaching treatment of IgAN in patients with persistent proteinuria >1 g/day based on RAS inhibition and SOC was not satisfactory. Despite optimized SOC, the long-term follow-up of patients enrolled in the STOP-IgAN RCT showed that 50% of patients progressed to 40% loss of eGFR or RSKD after 7.4 years [

30], Moreover, in recent RCTs the eGFR loss in patients with optimal SOC was about - 5 ml/min/1.73 m2, which is to be considered unacceptable. Meanwhile it became clear that the proteinuria threshold >1 g/day was too high to select patients at risk of progression, hence excluding from active treatment approach those with lower levels. Indeed from the Validation Study of the Oxford Classification in IgA nephropathy (VALIGA) study the value of persistent proteinuria >0.5 <1 g/day was assessed in a large cohort of 1034 patients of IgAN from several European Countries [

31]; and more recent data from the UK registry for rare disease (RADAR study) [

8] indicated that lower threshold of proteinuria >0.4 g/day may be a significant risk for progression. Finally, several now drugs targeting individual pathogenetic factors have been reported and/or are on the study pipeline, suggesting a new revolution in treating IgAN.

Based on this data, KDIGO has prepared in 2024 a new guideline which was available for public review and now is about to be published in the final form ((KDIGO-IgAN-IgAV-Guideline-Public-Review-Draft-Data-Supplement_August-2024, n.d.).The main changes include the identification of patients at risk on a proteinuria threshold ≥ 0.5 g/day in patients, while on or off treatment. Moreover, the target of proteinuria reduction is set to values lower than 0.3 g/day, possibly needing multiple drug intervention.

There major news in the next KDIGO is the IgAN patients at risk of progression should receive simultaneous treatments with a double targeting approach: on one side aiming at preventing or reducing the immune complex mediated glomerular damage and in parallel on the other side aiming at limiting the consequences of the existing damage on glomerular loss and hyperfiltration. The list of new drugs active on either process is growing and this challenging to follow the entry of new treatment options that progress to authority approval and distribution to patients.

The most relevant news include drugs targeting a) the initial pathogenetic event of production of Gd-IgA1, b) the full explosion of inflammation, led by complement activation, c) the non-inflammatory progression, previously dominated by RAS inhibitors, now challenged by anti-endothelin A drugs, dual endothelin and angiotensin receptor antagonism (DEARA), sodium-glucose cotransporter -2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) and mineral corticosteroid receptor antagonists (MRA). Other drugs are on the pipeline, but we will focus on the most relevant recent publications of phase 2 or phase 3 RCT which is some cases led to FDA and EMA approval.

Treatment Targeting the First Pathogenetic Hit of IgAN: The Synthesis of Gd-IgA1

Polymeric IgA detected in kidney deposits of IgAN is the typical product of the mucosal associate lymphoid tissue (MALT) and the synthesis is elicited by environmental antigens, microbiota and their products [

32]. In IgAN Gd-IgA1 can be produced by gut associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) as well as by tonsils and nasopharynx-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT). The GALT surface of 300 m2 largely covers more than half of the IgA synthesis from other MALT sites (as the limited NALT). Hence, the Peyer’s patches, lymphoid follicles mostly represented in the terminal small intestine, are the most active site of production of Gd-IgA1 in patients with IgAN [

33]. In the MALT the antigens prime naïve B cells through T cell dependent and T cell-independent mechanisms [

34]. T cell independent pathway is activated via interleukins (lL-6 and IL-10), transforming growth factor (TGF-β), B cell activating factor (BAFF or BLyS), and a proliferative inducing ligand (APRIL). BAFF and APRIL bind the TNF receptor transmembrane activator (TACI) and promote B cell differentiation and proliferation. BAFF and APRIL are tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily cytokines which play a fundamental role in regulating IgA production by B cells and survival of IgA-producing plasma cells [

35,

36]. BAFF is particularly active on B cell maturation, survival and transition to mature B cells with immunoglobulin production. APRIL has a more precise role in later stages of B-cell differentiation and survival of long-lived plasma cells, located in the bone marrow and in the MALT to produce antibodies. The role of APRIL in IgAN is supported by several observations including IgA class antibody production and Gd-IgA1 synthesis (particularly in patients with IgAN) [

37].

Inhibiting Lymphocyte Proliferation

The first drug used to inhibit B and T lymphocyte proliferation was mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) which had conflicting reports, mostly negative in early small studies in White subjects and largely positive in trials in Asiatic subjects [

38]. A more recent Chinese study [

39] enrolled incident patients with biopsy within one month and active disease including proteinuria >1.0 g/day, eGFR >30 ml/min and crescents involving >10% <50% of the glomeruli or endocapillary hypercellularity or glomerular necrosis and limited tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis. The protocol had two arms a) prednisone 0.8-1 mg/Kg /day 2 months, tapering in 4 months and b) MMF 1.5 g/day added to half dose prednisone (0.4 mg/Kg/day). The primary endpoints were complete remission and changes in active proliferative lesions on a repeat biopsy. Results showed that the two regimens had similar benefits with fewer adverse events in patients receiving MMF and half dose of prednisone. The Mycophenolate Mofetil Among Patients with Progressive IgA nephropathy (MAIN) trial [

40] enrolled 170 Chinese patients with IgAN in an open label randomization to placebo or MMF at initial dose of 1.5 g/day tapered to 0.75 -1 g/day for 6 months. MMF was found to significantly reduce the risk of disease progression in respect to SOC alone. The AE were limited to mild and tolerable gastrointestinal symptoms. Infections (pneumonia) were reported in 16% of MMF, but also in 10% in SOC.

In a real word setting in Chinese national database recording data from 3964 patients with IgAN who initiated treatment within 30 days from renal biopsy [

41], two groups of 1973 patients on SOC (RASB) or in immunosuppressive care (CS with or without MMF) were selected by propensity score and compared. IS treatment was associated with a 40% lower risk of primary outcome of 40% decrease in eGFR or ESKD. The results were comparable in CS monotherapy and MMF alone and in patients with various proteinuria and eGFR levels. Great benefit was observed in patients with endocapillary hypercellularity (E1) and segmental glomerulosclerosis (S1) and without severe tubulo-interstitial lesions (T0-1).

B-Cell and Plasma Cell–Targeted Treatment

The first approach to B-cell treatment was to test rituximab, CD20 antibody in a small RCT enrolling 34 patients with IgAN and persistent proteinuria > 1 g despite RASB [

42]. The results were disappointing, failing to show any reduction in proteinuria or kidney function protection. Moreover, CD20 depletion did not modify levels of Gd-IgA1 or anti Gd-IgA1 antibodies, suggesting that CD20 were not implicated in the initial pathogenetic event. Indeed, depletion of CD20

+ B cells by rituximab was reported not to affect gut-resident plasma cells [

43].

The B cell target was moved to CD38 B cells and plasma cells [

44] considered to be more closely involved in the formation of Gd-IgA1 and the corresponding autoantibody. Felzartamab, a recombinant fully human monoclonal antibody against CD38, is under evaluation in a phase 2a trial (IGNAZ; NCT05065970) (

Table 1). The intention to treat analysis was performed in 48 subjects with IgAN enrolled across immune-mediated kidney diseases, including membranous nephropathy, lupus nephritis and antibody mediated rejection [

45]. In different doses (2 to 9 doses in 15 days-9 months) showed reduction of UPCR) over 6 months, which persisted ten months after the last dose. Rapid and durable reduction in IgA and Gd-IgA1 were also observed lasting 10 months after treatment. The AE were of moderate intensity and mostly infusion related reactions at the first administration.

The pivotal role of BAFF and APRIL in B cell activation leading to production of Gd-IgA1 supported the rationale for testing drugs targeting these two TNF superfamily cytokines [

35,

36,

37]. Sibeprenlimab, a humanized IgG2 monoclonal antibody that binds and neutralizes APRIL, was tested in a phase 2 ENVISION trial (NCT04287985) [

46]. Different doses of Sibeprenlimab (2,4,8 mg/Kg i.v.) were administered monthly in 155 patients (117 treated and 38 placebo) to assess efficacy and safety. A significant reduction in proteinuria of -62.0±5.7% was detected with 53% reduction as compared to placebo with the highest drug dose. Proteinuria complete remission was observed in 26.3% of treated patients, and in 2.6% of patients receiving placebo. Levels of Gd-IgA1 resulted reduced by 40% and IgAIC by 66% after 12 months with sibeprenlimab 8 mg/Kg/iv monthly. Both Gd-IgA1 and IgAIC levels had a rebound 5 months after treatment discontinuation. In an explorative analysis kidney function was protected as in the 38 patients receiving the dose of 8 mg/kg the treatment difference in eGFR slope relative to placebo was 5.08 (0.5 to 9.6) ml/min/1.73m2 with eGFR loss of -1.5 ml/min/1.73m2 in patients receiving the highest doses in respect to placebo - 7 ml/min/1.73m2. Safety was like placebo and adverse events (78% versus 71% AE) mostly mild, without increased risk of infection.

Zigakibart (BION-1301) is a novel anti-APRIL humanized monoclonal antibody tested which provided proteinuria and Gd-IgA1 reduction in phase 1 and 2 studies [

47] under evaluation in a phase 2 ongoing study BEYOND (NCT05852938).

Atacicept, a fully humanized fusion protein acting as decoy receptor neutralizing both APRIL and BAFF, in a phase 2 study ORIGIN 3 (NCT04716231) [

48], in the combined group of 75 mg and 150 mg once weekly s.c. injection resulted in a reduction of UPCR at 36 weeks by 31%. Circulating Gd-IgA1 levels were reduced by 40%. Safety was like placebo (AE 73% in treatment and 79% in the placebo groups).

The long-term open-label extension study recently reported the effects of atacicept 150 mg s.c. weekly in 113 subjects with IgAN for 60 weeks after the end of the phase 2b study [

49] and followed up to 96 weeks (31 patients in former placebo were treated for 60 weeks).

Patients showed a sustained decrease in UPCR (-52 ± 5%) versus baseline and in Gd-IgA1 (-66 ± 2%) and percentage of patients with hematuria (-75%). The eGFR annualized slope over the 96 weeks was -0.6 ± 0.5 ml/min/min/1.73 m2, unchanged after the 36 weeks of blind treatment. The drug was well tolerated, discontinued in 2 cases for mild and transient AE (injection site pain and Hepatitis B positive test). Serious infections (in three cases) were resolved without sequelae and no opportunistic or fatal infections occurred.

Similar encouraging data are reported in preliminary reports with telitacicept (NCT05596708) [

50] and povetacicept (NCT05732402) [

51]

Treatment Targeting the Amplification of Glomerular Inflammation: The Complement Cascade

In IgAN complement activation plays a pivotal role in the development and perpetuation of inflammation following IgAIC deposition [

52]. The absence of C1q suggests that complement is activated via alternative and lectin pathways and activation occurs after IgAIC deposits within the glomerular area [

53]. The attempt to inhibit the lectin pathway by narsoplimab, a fully human monoclonal antibody targeting the lectin regulatory enzyme MASP2, was interrupted after the finding of no effect on proteinuria at interim analysis of the ARTEMIS phase 3 RTC (NCT0308033) [

52].

The inhibition of the alternative pathway seems presently the most appropriate approach. Iptacopan specifically binds to factor B and inhibits the alternative complement pathway. It was tested in the phase 2 APPLAUSE study (NCT04578834) [

54] at doses of 19, 50 or 150 mg for 6 months in 112 patients (87 in treatment and 25 in placebo). A dose dependent proteinuria change was detected at 3 months or 6 months. Mild adverse events were reported and not related to the drug. The interim analysis of 250 patients in the ongoing, phase 3 APPLAUSE-IgAN RCT testing Iptacopan 150 mg for 9 months detected a significant reduction in proteinuria (38.3% lower with iptacopan than with placebo) [

55]. The reduction in proteinuria was consistent across subgroups with different geographic regions, baseline proteinuria, GFR, hematuria, MEST-C scores or co-treatment with SGLT2i. Membrane attack complex (sC5b-9) high levels found at baseline returned to normal levels. Safety profile was good with no increase in the risk of infection in the treatment group. Iptacopan was approved in 2024 for the reduction of proteinuria in adults with IgAN at risk of rapid disease progression (UPCR ≥1.5 g/g).

A recent report on ravulizumab [

56] - a long-acting complement C5 inhibitor targeting the terminal complement pathway – tested in the phase 2 study SANCTUARY RCT, (NCT04564339) showed in 66 patients enrolled a significant reduction in proteinuria (30,1% treatment effect versus placebo). Ravulizumab was well tolerated with adverse event profile like that for placebo. Immediate and complete inhibition of terminal complement cascade was detected and C5 concentrations were undetectable.

The Expanded Supportive Care (Non-Immunologic Treatment) for Patients with IgAN: SGLT2 Inhibitors and Anti-Endothelin A

The therapy targeting the pathogenetic events of IgAN should be started in the early phases, but it must be added on an optimized SOC targeting the chronic and sclerotic progression of the disease (

Figure 1). This target remains all over the natural history of IgAN and must be addressed for lifelong.

The introduction of RASB in the treatment of IgAN across the age spectrum was fully recognized since KDIGO 2021 as a pillar of the SOC care [

26]. However, as mentioned above, several patients remained at risk of CKD progression despite prolonged RASB and optimized SOC, hence great interest was attracted by new drug primarily tested in diabetic patients, found to provide a reduction in proteinuria and eGFR loss in CDK [

57].

The first impressive report showed that SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin reduced the progression of a subgroup of 270 IgAN patients to the endpoint of 50% eGFR loss or ESKD with a favorable safety profile [

58]. Proteinuria was reduced by 26% relative to placebo

. Dapagliflozin was approved by the US FDA and EMA for CKD in adults, including IgAN

.

Sparsentan, a dual endothelin and angiotensin II receptor antagonist (DEARA) provided excellent results in the PROTECT Phase 3 RCT (NCT03762850). Sparsentan 400 mg or irbesartan 300 mg were distributed to 404 adults with IgAN, eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2 with persistent proteinuria >1 g/day despite of 3 months of optimized SOC. The interim analysis showed change in UPCR at week 36 of 49% versus 15% in placebo [

59]. In 2023 Sparsentan received FDA accelerated approval for reduction of proteinuria in IgAN at risk of rapid disease progression (UPCR ≥1.5 g/g). In the final report after 2 years [

60] proteinuria remained significantly lower in sparsentan group (reduction of 31% versus 11%). The eGFR 2-year chronic slope, starting from week 6 to week 110, was significantly different (p=0.037). Protection from 40 % eGFR reduction, ESKD or all-cause mortality was significantly better in sparsentan group. FDA granted full approval to sparsentan in 2025 for slowing kidney function decline in adults with IgAN at risk of disease progression based on final PROTECT trial data.

Selective endothelin A receptor antagonists represent a new exciting target. Recent reports provided excellent data on selective endothelin receptor antagonists (ARA) in addition to RASB which may allow fine dose tuning and possible stronger ET-A receptor inhibition than DEARA.

Atrasentan, a selective ET-A receptor inhibitor, was tested in the phase 3 ALIGN RCT (NCT04573478). The interim analysis of 270 patients in week 36 showed a significant reduction of UPCR in treated patients 36.1% than with placebo [

61]. Fluid retention was more frequent in the atrasentan group (11.2% versus 8.2%) but did not lead to drug discontinuation. No cases of cardiac failure or severe edema occurred. Atrasentan received in 2025 FDA accelerated approval for the reduction of proteinuria in adults with IgAN at risk of rapid disease progression.

The ET-A receptor SC0062 NCT05687890 [

62] differs from sparsentan and atrasentan because of a higher selectivity for ET-A compared with ET-B receptors, which may be relevant for both efficacy and safety profile, particularly fluid retention and edema. In 131 patients with IgAN the percentage change from UPCR after 12 weeks of treatment with various doses of SC0062 was significant (up to -38.1% versus placebo), without an increase in peripheral edema.

The new mineralcorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA) finerenone may provide additional benefits when added on RASB, as reported a recent meta-analysis [

63].

Final Considerations

Treatment of IgAN is a rapidly evolving area [

64]. New options are being offered and most of the interest is focused on drugs targeting one by one specific factors playing a role in the pathogenesis or the progression of IgAN. These studies offer a unique possibility to identify targets for treatment leading to precision medicine in IgAN. However, the process is likely to take time, since these ongoing or recently published studies were planned just to prove the efficacy of the experimental drug in reducing proteinuria - usually after 9 months of treatment- and eGFR decline over two years of continuous treatment or wash-out observation. The plan of these studies has been driven by the need for industries to prove pre-defined standard benefits and obtain the authority’s approval. This step was mandatory but for real word application we should consider that patients were generally selected just because of persistent proteinuria despite SOC without considering a) duration of the previous disease, b) activity and chronicity clinical and histological signs in coincidence with the initiation of the treatment or c) presence in circulation or in kidney tissue of markers of the treatment target. For the new drugs we do not have available data on the duration of treatment needed to obtain long term benefits. Possible adverse consequences of long-term exposure are unknown. Moreover, with the lack of any comparative study, doctors are tempted to use all possible medications together (albeit one by one appropriate), such as SGLT2i and anti-endothelin in addition to anti RASB to optimize the anti-inflammatory treatment arm. Similarly, it is tempting for active cases to target the immune process with intestinal released formulation of budesonide adding on an anti-complement drug. We simply do not have data on the benefits of these associations. Small series of real word experiences that will likely to be reported at congresses will provide a limited contribution to understanding specific indications in a disease so complex and multifaceted as IgAN, since selection criteria will likely be variable. The natural history of IgAN is long-lasting, with likely phases of activity and remission after some treatments and the understanding of the most profitable treatment combination and appropriate timing will require collaborative data analysis on large cohorts form international collaboration. Artificial intelligence could be a valid means to analyze big numbers and derive personalized indications. Presently there are excellent flow-charts available in publications [

64,

65] and on the web that can help our choice, but each algorithm is likely to be modified in the next months/years after the influence of new publications.

The cost of these new drugs is a worrying issue, rendering them not available for public distribution in most developing Countries. These new treatments are not affordable for many patients who are not covered by public or private insurance. There is a high risk of patients’ frustration for feeling the loss of a therapeutic opportunity. We should consider that some “past therapies” for IgAN as CS or MMF still have a room everywhere, in Countries where patients cannot effort the cost of the new drugs but also in developed Countries. Patients in phase of active IgAN, based on clinical and histological well-known markers including rapidity of function decline, presence of severe microscopic hematuria and histological markers and not on proteinuria only, should be offered, in addition to SOC, treatment with proven benefits and limited adverse events, since irreversible progression cannot be halted once established. The severe side effects of CS pulses in real word excellent practice are rather limited [

27,

65,

66] and the number of CS pulses was variable in several reports with similar good results [67]. MMF at reduced doses in the large Chinese study [

40] was found to be effective and safe. Oral CS at moderate dose, or methylprednisolone pulses and MMF are part of the present armamentarium to treat IgAN looking at the future without forgetting the past.

The production galactose-deficient IgA1 (Gd-IgA1) (hit 1) induces the formation of auto-antibodies anti-Gd-IgA1 (hit 2) resulting in circulating IgA immune complexes (IgAIC) (hit 3). The glomerular inflammatory reaction following the deposition of IgAIC triggers mesangial cell proliferation, release of cytokines and activation of the complement system, leading to full development of IgAN (hit 4). In this phase the kidney functional reserve is activated and compensates for the early loss of glomerular function, hence eGFR is maintained, but as the chronic process activates glomerular sclerosis and tubule-interstitial damage, glomerular hyperfiltration and progressive loss of kidney function occur.

References

- Berger, J.; Hinglais, N. Intercapillary deposits of IgA-IgG. J Urol Nephrol (Paris). 1968, 74, 694–695. [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekaran, A.; Julian, B.A.; Rizk, D.V. IgA Nephropathy: An Interesting Autoimmune Kidney Disease. Am J Med Sci. 2021, 361, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell MW, Reinholdt J, Kilian M: Anti-inflammatory activity of human IgA antibodies and their Fab alpha fragments: inhibition of IgG-mediated complement activation. Eur J Immunol 1989, 19, 2243–2249. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RJWyatt, B.J. IgA nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2013, 368, 2402–2414. [Google Scholar]

- Coppo, R. Clinical and histological risk factors for progression of IgA nephropathy: an update in children, young and adult patients. J Nephrol. 2017, 30, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geddes, C.C.; Rauta, V.; Gronhagen-Riska, C.; et al. Bartosik LP, Jardine AG, Ibels LS, Pei Y, Cattran DC. A tricontinental view of IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003, 18, 1541–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbour, S.J.; Coppo, R.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.H.; Suzuki, Y.; Matsuzaki, K.; Katafuchi, R.; Er, L.; Espino-Hernandez, G.; Kim, S.J.; Reich, H.N.; et al. Evaluating a New International Risk-Prediction Tool in IgA Nephropathy. JAMA Intern Med. 2019, 179, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitcher, D.; Braddon, F.; Hendry, B.; Mercer, A.; Osmaston, K.; Saleem, M.A.; Steenkamp, R.; Wong, K.; Turner, A.N.; Wang, K.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes in IgA Nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023, 18, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, S.J.; Coppo, R.; Er, L.; Russo, M.L.; Liu, Z.H.; Ding, J.; Katafuchi, R.; Yoshikawa, N.; Xu, H.; Kagami, S.; et al. International IgA Nephropathy Network. Updating the International IgA Nephropathy Prediction Tool for use in children. Kidney Int. 2021, 99, 1439–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante, B.; Rossini, M.; Di Lorenzo, A.; Coviello, N.; Giuseppe, C.; Gesualdo, L.; Giuseppe, G.; Stallone, G. Recurrence of immunoglobulin A nephropathy after kidney transplantation: a narrative review of the incidence, risk factors, pathophysiology and management of immunosuppressive therapy. Clin Kidney J. 2020, 13, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Kiryluk, K.; Novak, J.; Moldoveanu, Z.; Herr, A.B.; Renfrow, M.B.; Wyatt, R.J.; Scolari, F.; Mestecky, J.; Gharavi, A.G.; Julian, B.A. The pathophysiology of IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011, 22, 1795–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattran, D.C.; Floege, J.; Coppo, R. Evaluating Progression Risk in Patients With Immunoglobulin A Nephropathy. Kidney Int Rep. 2023, 8, 2515–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozzi, C.; Bolasco, P.G.; Fogazzi, G.B.; Andrulli, S.; Altieri, P.; Ponticelli, C.; Locatelli, F. Corticosteroids in IgA nephropathy: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999, 353, 883–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CManno, D.D. Torres, M. Rossini, F. Pesce, and F. P. Schena, Randomized controlled clinical trial of corticosteroids plus ACE-inhibitors with long-term follow-up in proteinuric IgA nephropathy. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 2009, 24, 3694–3701. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, G.; Jiang, L.; Singh, A.K.; Wang, H. Combination therapy of prednisone and ACE inhibitor versus ACE-inhibitor therapy alone in patients with IgA nephropathy: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009, 53, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauen, T.; Eitner, F.; Fitzner, C.; Sommerer, C.; Zeier, M.; Otte, B.; Panzer, U.; Peters, H.; Benck, U.; Mertens, P.R.; et al. STOP-IgAN Investigators. Intensive Supportive Care plus Immunosuppression in IgA Nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2015, 373, 2225–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Zhang, H.; Wong, M.G.; Jardine, M.J.; Hladunewich, M.; Jha, V.; Monaghan, H.; Zhao, M.; Barbour, S.; Reich, H.; et al. TESTING Study Group. Effect of Oral Methylprednisolone on Clinical Outcomes in Patients with IgA Nephropathy: The TESTING Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017, 318, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floege, J.; Feehally, J. Treatment of IgA nephropathy and Henoch-Schönlein nephritis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013, 9, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, J.; Wong, M.G.; Hladunewich, M.A.; Jha, V.; Hooi, L.S.; Monaghan, H.; Zhao, M.; Barbour, S.; Jardine, M.J.; Reich, H.N.; et al. TESTING Study Group. Effect of Oral Methylprednisolone on Decline in Kidney Function or Kidney Failure in Patients With IgA Nephropathy: The TESTING Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2022, 327, 1888–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, J.; Lafayette, R.; Kristensen, J.; Stone, A.; Cattran, D.; Floege, J.; Tesar, V.; Trimarchi, H.; Zhang, H.; Eren, N.; et al. NefIgArd Trial Investigators. Results from part A of the multi-center, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled NefIgArd trial, which evaluated targeted-release formulation of budesonide for the treatment of primary immunoglobulin A nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2023, 103, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafayette, R.; Kristensen, J.; Stone, A.; Floege, J.; Tesař, V.; Trimarchi, H.; Zhang, H.; Eren, N.; Paliege, A.; Reich, H.N.; et al. NefIgArd trial investigators. Efficacy and safety of a targeted-release formulation of budesonide in patients with primary IgA nephropathy (NefIgArd): 2-year results from a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023, 402, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippone, E.J.; Gulati, R.; Farber, J.L. The road ahead: emerging therapies for primary IgA nephropathy. Front Nephrol. 2025, 5, 1545329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, C.; Andrulli, S.; Del Vecchio, L.; Melis, P.; Fogazzi, G.B.; Altieri, P.; Ponticelli, C.; Locatelli, F. Corticosteroid effectiveness in IgA nephropathy: long-term results of a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004, 15, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Glomerulonephritis Work Group, “KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Glomerulonephritis,” Kidney International Supplements 2012, 2, 1–274.

- Rauen, T.; Wied, S.; Fitzner, C.; Eitner, F.; Sommerer, C.; Zeier, M.; Otte, B.; Panzer, U.; Budde, K.; Benck, U.; et al. STOP-IgAN Investigators. After ten years of follow-up, no difference between supportive care plus immunosuppression and supportive care alone in IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2020, 98, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovin, B.H.; Adler, S.G.; Barratt, J.; Bridoux, F.; Burdge, K.A.; Chan, T.M.; Cook, H.T.; Fervenza, F.C.; Gibson, K.L.; Glassock, R.J.; et al. Executive summary of the KDIGO 2021 Guideline for the Management of Glomerular Diseases. Kidney Int. 2021, 100, 753–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locatelli, F.; Del Vecchio, L.; Ponticelli, C. Systemic and targeted steroids for the treatment of IgA nephropathy. Clin Kidney J 2023, 16 Suppl 2, ii40–ii46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brattsand R, Thalén A, Roempke K, Källström L, Gruvstad E, Influence of 16 alpha, 17 alpha-acetal substitution and steroid nucleus fluorination on the topical to systemic activity ratio of glucocorticoids. J Steroid Biochem, 1982, 16, 779–786. [CrossRef]

- Peruzzi, L.; Coppo, R. Expected and verified benefits from old and new corticosteroid treatments in IgA nephropathy: from trials in adults to new IPNA-KDIGO guidelines. Pediatr Nephrol, Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauen, T.; Wied, S.; Fitzner, C.; Eitner, F.; Sommerer, C.; Zeier, M.; Otte, B.; Panzer, U.; Budde, K.; Benck, U.; et al. STOP-IgAN Investigators. After ten years of follow-up, no difference between supportive care plus immunosuppression and supportive care alone in IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2020, 98, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppo, R.; Troyanov, S.; Bellur, S.; Cattran, D.; Cook, H.T.; Feehally, J.; Roberts, I.S.; Morando, L.; Camilla, R.; Tesar, V.; et al. VALIGA study of the ERA-EDTA Immunonephrology Working Group. Validation of the Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy in cohorts with different presentations and treatments. Kidney Int. 2014, 86, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesualdo, L.; Di Leo, V.; Coppo, R. The mucosal immune system and IgA nephropathy. Semin Immunopathol. 2021, 43, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppo, R. The intestine-renal connection in IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015, 30, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagarasan, S.; Kawamoto, S.; Kanagawa, O.; Suzuki, K. Adaptive immune regulation in the gut: T cell-dependent and T cell-independent IgA synthesis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010, 28, 243–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.K.; Barratt, J.; Liew, A.; Zhang, H.; Tesar, V.; Lafayette, R. The role of BAFF and APRIL in IgA nephropathy: pathogenic mechanisms and targeted therapies. Front Nephrol. 2024, 3, 1346769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.G.; Alvarez, M.; Suzuki, H.; Hirose, S.; Izui, S.; Tomino, Y.; Huard, B.; Suzuki, Y. Pathogenic Role of a Proliferation-Inducing Ligand (APRIL) in Murine IgA Nephropathy. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0137044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.S.; Yang, S.H.; Choi, M.; Kim, H.R.; Kim, K.; Lee, S.; Moon, K.C.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.P.; et al. The Role of TNF Superfamily Member 13 in the Progression of IgA Nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016, 27, 3430–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.N.; Tang, S.C.; Schena, F.P.; Novak, J.; Tomino, Y.; Fogo, A.B.; Glassock, R.J. IgA nephropathy. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016, 2, 16001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.H.; Le, W.B.; Chen, N.; Wang, W.M.; Liu, Z.S.; Liu, D.; Chen, J.H.; Tian, J.; Fu, P.; Hu, Z.X.; et al. Mycophenolate Mofetil Combined With Prednisone Versus Full-Dose Prednisone in IgA Nephropathy With Active Proliferative Lesions: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017, 69, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou FF, Xie D, Wang J, Xu X, Yang X, Ai J, Nie S, Liang M, Wang G, Jia N; MAIN Trial Investigators. Effectiveness of Mycophenolate Mofetil Among Patients With Progressive IgA Nephropathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023, 6, e2254054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; Sun, J.; Xu, G.; Wang, C.; Zhou, S.; Nie, S.; Li, Y.; Su, L.; Chen, R.; et al. Immunosuppression versus Supportive Care on Kidney Outcomes in IgA Nephropathy in the Real-World Setting. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023, 18, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafayette, R.A.; Canetta, P.A.; Rovin, B.H.; Appel, G.B.; Novak, J.; Nath, K.A.; Sethi, S.; Tumlin, J.A.; Mehta, K.; Hogan, M.; Erickson, S.; et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Rituximab in IgA Nephropathy with Proteinuria and Renal Dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017, 28, 1306–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzan, M.; Ko, H.M.; Rosenstein, A.K.; Pourmand, K.; Colombel, J.F.; Mehandru, S. Efficient long-term depletion of CD20+ B cells by rituximab does not affect gut-resident plasma cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018, 1415, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maixnerova, D.; El Mehdi, D.; Rizk, D.V.; Zhang, H.; Tesar, V. New treatment strategies for IgA nephropathy: targeting plasma cells as the main source of pathogenic antibodies. Clin Med. 2022, 11, 2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floege, J.; Lafayette, R.; Barratt, J.; Schwartz, B.; Manser, P.T.; Patel, U.D.; Pineda, L.; Faulhaber, N.; Boxhammer, R.; Haertle, S.; et al. i: (anti-CD38) in patients with IgA Nephropathy: interim results from the IGNAZ study (abstract) Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2024; 39, (Supplement 1, abstract 425).

- Mathur, M.; Barratt, J.; Chacko, B.; Chan, T.M.; Kooienga, L.; Oh, K.H.; Sahay, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Wong, M.G.; Yarbrough, J.; et al. ENVISION Trial Investigators Group. A Phase 2 Trial of Sibeprenlimab in Patients with IgA Nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2024, 390, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, J.; Hour, B.; Kooienga, L.; Roy, S.; Schwartz, B.; Siddiqui, A.; Tolentino, J.; Iyer, S.P.; Stromatt, C.; Endsley, A.; et al. POS-109 Interim results of phase 1 and 2 trials to investigate the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and clinical activity of BION-1301 in patients with IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. Rep. 2022, 7, S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafayette, R.; Barbour, S.; Israni, R.; Wei, X.; Eren, N.; Floege, J.; Jha, V.; Kim, S.G.; Maes, B.; Phoon, R.K.S.; et al. A phase 2b, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of atacicept for treatment of IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, 1306–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barratt, J.; Barbour, S.J.; Brenner, R.M.; Cooper, K.; Wei, X.; Eren, N.; Floege, J.; Jha, V.; Kim, S.G.; Maes, B.; et al. ORIGIN Phase 2b Investigators. Long-Term Results from an Open-Label Extension Study of Atacicept for the Treatment of IgA Nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2025, 36, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Liu, L.; Hao, C.; Li, G.; Fu, P.; Xing, G.; Zheng, H.; Chen, N.; Wang, C.; Luo, P.; et al. Randomized Phase 2 Trial of Telitacicept in Patients with IgA Nephropathy with Persistent Proteinuria. Kidney Int. Rep. 2023, 8, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan, A.; Yalavarthy, R.; Kim, D.K.; Moon Jy Park, I.; Mandayam, S.A.; et al. Results from longer follow-up with povetacicept, an enhanced dual BAFF/APRIL antagonist, in IgA nephropathy (RUBY-3 study). J Am Soc Nephrol. 2024, 35, FRPO854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravaca-Fontán, F.; Gutiérrez, E.; Sevillano, Á.M.; Praga, M. Targeting complement in IgA nephropathy. Clin Kidney J. 2023, 16 (Suppl 2), ii28–ii39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, R.C.; Abramowsky, C.R.; Tisher, C.C. IgA nephropathy. Am J Pathol. 1974, 76, 123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Rizk, D.V.; Perkovic, V.; Maes, B.; Kashihara, N.; Rovin, B.; Trimarchi, H.; PK; Charney, A. ; Barratt, J. Results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled Phase 2 study propose iptacopan as an alternative complement pathway inhibitor for IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkovic, V.; Barratt, J.; Rovin, B.; Kashihara, N.; Maes, B.; Zhang, H.; Trimarchi, H.; Kollins, D.; Papachristofi, O.; Jacinto-Sanders, S.; et al. Alternative Complement Pathway Inhibition with Iptacopan in IgA Nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2025, 392, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafayette, R.; Tumlin, J.; Fenoglio, R.; Kaufeld, J.; Pérez Valdivia, M.Á.; Wu, M.S.; Susan Huang, S.H.; Alamartine, E.; Kim, S.G.; Yee, M.; et al. SANCTUARY Study Investigators. Efficacy and Safety of Ravulizumab in IgA Nephropathy: A Phase 2 Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2025, 36, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floege, J.; Bernier-Jean, A.; Barratt, J.; Rovin, B. Treatment of patients with IgA nephropathy: a call for a new paradigm. Kidney Int. 2025, 107, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, D.C.; Toto, R.D.; Stefánsson, B.V.; Jongs, N.; Chertow, G.M.; Greene, T.; Hou, F.F.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; Correa-Rotter, R.; et al. DAPA-CKD Trial Committees and Investigators. A pre-specified analysis of the DAPA-CKD trial demonstrates the effects of dapagliflozin on major adverse kidney events in patients with IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2021, 100, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Radhakrishnan, J.; Alpers, C.E.; Barratt, J.; Bieler, S.; Diva, U.; Inrig, J.; Komers, R.; Mercer, A.; Noronha, I.L.; et al. PROTECT Investigators. Sparsentan in patients with IgA nephropathy: a prespecified interim analysis from a randomised, double-blind, active-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2023, 401, 1584–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovin, B.H.; Barratt, J.; Heerspink, H.J.L.; Alpers, C.E.; Bieler, S.; Chae, D.W.; Diva, U.A.; Floege, J.; Gesualdo, L.; Inrig, J.K.; et al. DUPRO steering committee and PROTECT Investigators. Efficacy and safety of sparsentan versus irbesartan in patients with IgA nephropathy (PROTECT): 2-year results from a randomised, active-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023, 402, 2077–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Du, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, B.; Bi, G.; Xu, C.; Luo, Q.; Wu, H.; Wan, J.; et al. The Selective Endothelin Receptor Antagonist SC0062 in IgA Nephropathy: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2025, 392, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Si, F.L.; Chen, P.; Hou, W.Y.; Yang, H.Y.; Lv, J.C.; Shi, S.F.; Zhou, X.J.; Liu, L.J.; Zhang, H. Effectiveness and safety of finerenone in non-diabetic patients with IgA nephropathy. J Nephrol. 2025, 1. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Karoui, K.; Fervenza, F.C.; De Vriese, A.S. Treatment of IgA Nephropathy: A Rapidly Evolving Field. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2024, 35, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floege, J.; Bernier-Jean, A.; Barratt, J.; Rovin, B. Treatment of patients with IgA nephropathy: a call for a new paradigm. Kidney Int. 2025, 107, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baragetti, I.; Del Vecchio, L.; Ferrario, F.; Alberici, F.; Amendola, A.; Russo, E.; Ponti, S.; Di Palma, A.M.; Pani, A.; Rollino, C.; et al. Italian Group of Steroids in IgAN. The safety of corticosteroid therapy in IGA nephropathy: analysis of a real-life Italian cohort. J Nephrol. 2025, 38, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe-Kusunoki, K.; Nakazawa, D.; Yamamoto, J.; Matsuoka, N.; Kaneshima, N.; Nakagaki, T.; Yamamoto, R.; Maoka, T.; Iwasaki, S.; Tsuji, T.; et al. Comparison of administration of single- and triple-course steroid pulse therapy combined with tonsillectomy for immunoglobulin A nephropathy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021, 100, e27778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).