1. Introduction

Low-resource languages lack sufficient linguistic resources, such as the large-scale annotated corpus, dictionaries, computational tools, and digitized texts required for developing effective Natural Language Processing (NLP) systems. Unlike high-resource languages such as English, Chinese, Spanish, or French, low-resource languages face significant challenges in data availability, making it difficult to train and evaluate models for tasks like machine translation, speech recognition, and text classification [

1,

2,

3].

Turkic languages (such as Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Uzbek, Tatar, Azerbaijan, Turkish, etc.) are also considered low-resource, as most of them suffer from limited availability of high-quality linguistic data and the parallel corpus necessary for training NLP models. In recent years, the development and evaluation of machine translation systems for low-resource Turkic languages have gained increasing attention in the field of natural language processing [

4,

5]. For many low-resource languages, the lack of parallel sente

nce data poses a serious challenge, significantly limiting the development of effective machine translation systems and other NLP applications. Without a high-quality parallel corpus for specific languages, it is impossible to train accurate models for translation and other tasks such as text analysis and generation. One solution for the lack of parallel data is to create a synthetic corpus [

6,

7]. Another common approach to obtaining create synthetic corpus using machine translation, translating the source text from one language into another. Monolingual texts are used to create parallel data through machine translation. However, the method faces challenges, primarily poor translation quality. Machine translation for low-resource languages may be insufficiently accurate, especially when the system is trained on limited data. Translation errors may include incorrect meaning transfer, grammatical mistakes, and misinterpretation of phrases, all of which negatively affect the quality of the resulting parallel corpus.

Many studies on low-resource languages have explored the use of a pivot language—most commonly English—for generating synthetic a parallel corpus [

8,

9]. This approach helps overcome the lack of direct translation data between two under-resourced languages by leveraging the rich linguistic resources available for English [

10]. However, this method is not always optimal, especially for closely related languages such as Kyrgyz and Kazakh. Using English as an intermediate step can lead to the loss of semantic and grammatical nuances specific to Turkic languages, ultimately reducing the quality of the resulting data. Therefore, more direct and linguistically informed approaches to corpus creation are necessary for such language pairs.

For the Kazakh-Kyrgyz language pair, publicly available parallel data is extremely limited, which presents a significant challenge for developing and training effective Neural Machine Translation (NMT) models. There is a noticeable lack of research and publications on neural machine translation for the Kazakh-Kyrgyz language pair [

11].

An effective methodology and process of creating a corpus of parallel sentences in the Kazakh and Kyrgyz languages are presented in this article.

2. Low-Resource Languages and Creation of Parallel Sentences Datasets

One of the main challenges in working with low-resource languages is the lack of sufficient parallel sentence datasets, which are essential for training and evaluating machine translation models. This scarcity highlights the urgent need to develop and expand a parallel corpus for such languages [

12,

13]. For low-resource languages, namely for Turkic languages and Indonesian languages, bilingual dictionaries were obtained for the language pairs Uyghur-Kazakh, Kazakh-Kyrgyz, Kyrgyz-Uyghur [

13]. For Asian language pairs – Japanese, Indonesian, Malay paired with Vietnamese, an innovative approach is proposed to build a bilingual corpus from comparable data and phrase pivot translation on an existing bilingual corpus of the languages paired with English [

14].

The creation of parallel data is a multifaceted process that requires the use of various methods, especially for low-resource languages. This is where the idea of using AI comes in. First of all, one can rely on the existing parallel dataset, which is the simplest and fastest approach. Many languages already have available parallel data, such as:

• OPUS — an extensive repository of parallel datasets in various languages, including data for many language pairs [

15];

• TED Talks — subtitles for TED talks are often available in multiple languages, allowing the creation of a parallel dataset [

16];

• Europarl — parallel dataset from European Parliament proceedings in multiple languages [

17].

OPUS is an open-access collection of multilingual parallel datasets compiled from various sources that are widely used for machine translation development. The OPUS database is maintained and continuously updated by Uppsala University (Sweden) [

15]. The OPUS datasets include several key resources:

• Europarl – Official documents of the European Parliament.

• GNOME, KDE, Ubuntu – Software interfaces and technical documentation.

• Tanzil – Multilingual translations of the Quran.

• OpenSubtitles – Movie subtitles in multiple languages.

• WikiMatrix – Multilingual parallel texts extracted from Wikipedia.

OPUS datasets are widely used to evaluate machine translation quality, train multilingual models, and gather data for low-resource languages. Since OPUS texts cover various styles and topics, they are highly suitable for training neural translation systems. OPUS datasets can be accessed via Hugging Face Datasets, OPUS API, or processed using tools such as Moses and FastText [

18], and in [

19], examined the quality of translation using real data sourced from various platforms, including news websites and internet resources. This allowed for an assessment of how machine translation systems perform under actual usage conditions. In recent years, the field of Machine Translation (MT) and NLP has undergone significant changes due to the introduction of deep learning methods and neural networks. One of the first breakthroughs in this area was the transition from statistical translation methods to neural networks, where they proposed a neural machine translation model with an Attention Mechanism, which significantly improved translation results compared to previous methods [

20]. The paper [

21] outlines six key challenges in NMT, including data sparsity, handling rare words, and difficulties in translating long sentences. Their work emphasized the need for larger training datasets and architectural modifications to overcome these issues. In [

22], XLM-R was introduced, a cross-lingual language model that demonstrated improvements in low-resource translation by leveraging multilingual pre-training. Meta AI’s "No Language Left Behind" (NLLB) project further advanced translation quality for underrepresented languages [

23].

In [

24], four primary sources of data for corpus construction are identified: open internet resources, corpus data, user-generated content, and machine-generated data. The paper also outlines four approaches to creating an AI-assisted corpus: using third-party open sources, crowdsourcing, training models on proprietary data, and joint Corpus creation by humans and machines. The crowdsourcing approach is particularly noteworthy, as it allows for the expansion of the corpus through contributions from both professional and non-professional translators. In addition, the author emphasizes the importance of data multimodality (video, audio, text) and the shift from traditional dictionaries to the concept of multilingual terminology management. The paper also highlights the challenges of integrating AI algorithms into real-world applications, particularly in education and real-time online translation. This article [

25] presents recent research in the field of a parallel corpus, covering both the development of new resources and the improvement of methods for their utilization. The volume discusses the role of parallel corpora using the German-Spanish language pair as an example in translation studies and contrastive linguistics, as well as technical aspects of alignment, annotation, and search. The paper also introduces current projects on the creation of parallel and multimodal corpora in Europe, including real-world use cases. Furthermore, it highlights the significance of such corpus for developing bilingual resources, language teaching, and machine translation tasks.

These studies were reviewed to identify the effective strategies for creating and utilizing parallel corpus for low-resource languages. They provide valuable insights into the advantages and limitations of current datasets, translation models, and data acquisition methods. Building upon this foundation, the present research focuses on generating high-quality corpus for the Kazakh-Kyrgyz language pair.

3. Methods and Materials

3.1. Research Workflow

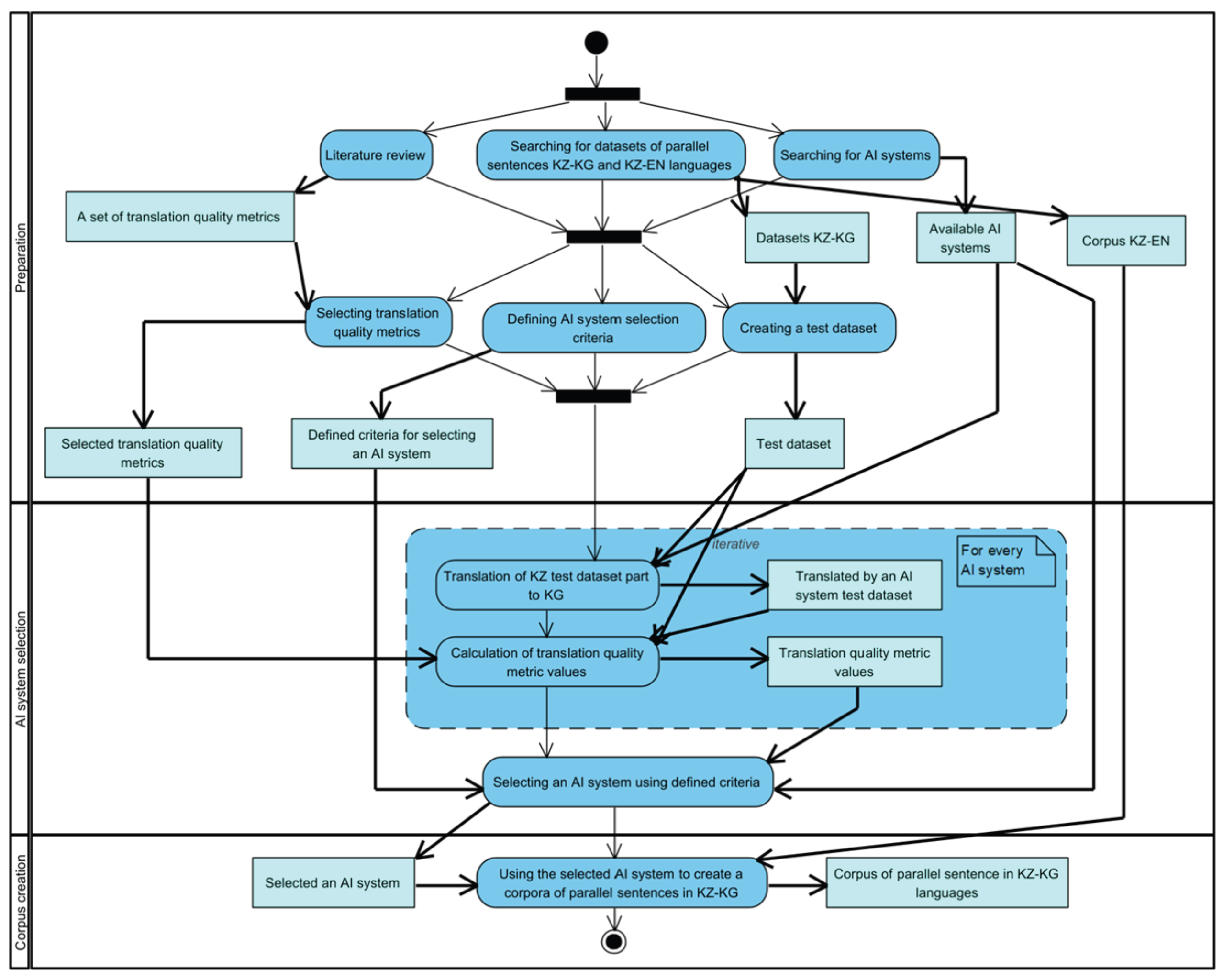

Figure 1 shows the three-phase workflow of the research studies completed and presented in this paper.

The workflow (

Figure 1) consists of three phases:

Preparation.

AI system selection.

Corpus creation.

During the first phase of research, the following activities will be carried out:

Literature review - conducting an extensive review of the current state of research in machine translation for low-resource languages, focusing on the Kazakh-Kyrgyz language pair and related technologies.

Searching for datasets of parallel sentences KZ-KG and KZ-EN languages - identifying available parallel corpus for the Kazakh-Kyrgyz and Kazakh-English language pairs from open data sources, such as OPUS, and evaluating their quality and coverage.

Searching for AI systems - investigating available AI systems and neural machine translation models that can be used for the Kazakh-Kyrgyz language pair, focusing on pre-trained models and open-source solutions.

Selecting translation quality metrics – choosing relevant evaluation metrics based on literature review to assess the quality and performance of the translation systems.

Defining AI system selection criteria – establishing clear criteria for selecting the most suitable AI model for translation tasks, considering factors like model architecture, efficiency, training data availability, and translation accuracy.

Creating a test dataset – curating a test dataset of parallel sentences from selected sources, ensuring it is balanced and representative of different domains for comprehensive evaluation of translation quality.

The second phase of the research consists of iteratively performed translation quality tests by individual AI systems (activities: Translation of KZ test dataset part to KG and Calculation of translation quality metric values), final AI system selection (activity: Selecting an AI system using defined criteria), and a method of step-by-step elimination of possibilities.

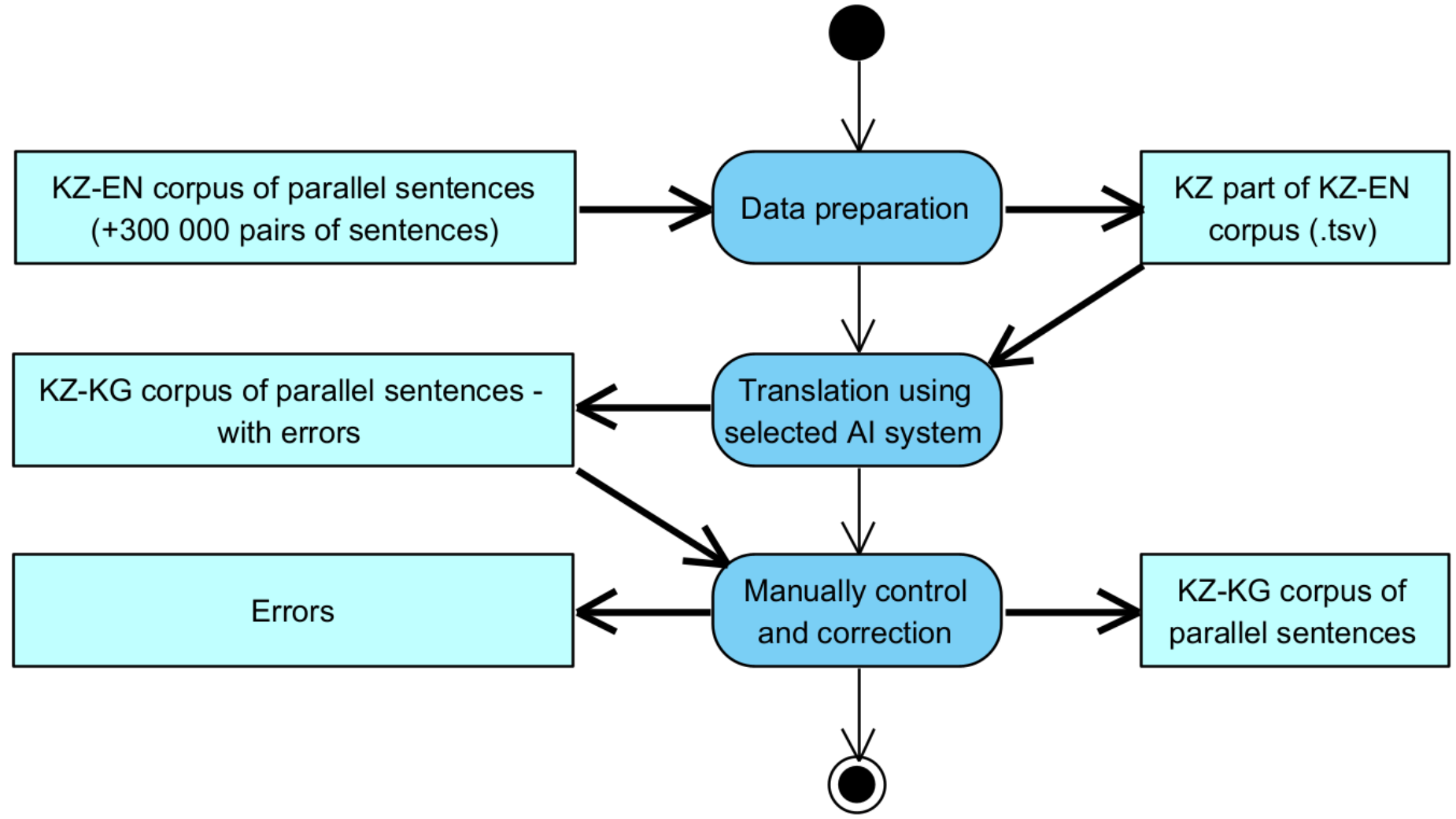

The third and final phase, Corpus creation, will consist of the translation of the KZ part of the corpus KZ-EN into the KG language. Details of this process are shown in

Figure 2.

During the computational work (translation) the hardware and software presented in

Table 1 were used.

3.2. Translation Quality Metrics

Translation quality metrics are essential for evaluating the effectiveness of machine translation, and commonly used metrics for assessing translation quality include BLEU, TER, and WER. However, these metrics often provide limited evaluation, which is why additional metrics for syntactic and semantic accuracy, such as COMET and chrF, are also used to offer a more comprehensive assessment of translation quality. The SacreBLEU baselines in corpus the following metrics from SacreBLEU [

26]. To assess the quality of the translated text, the following metrics are utilized:

• BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy) measures the overlap between machine-generated translations and reference translations. Sentence-level BLEU scores were calculated using the `sentence_bleu` function from SacreBLEU in Python [

27].

• WER (Word Error Rate) measures the number of errors (insertions, deletions, and substitutions) in the translated text. A lower WER indicates better translation accuracy.

• ChrF (Character n-gram F-score) evaluates translations at the character level, making it particularly useful for assessing morphologically rich languages. The “sacrebleu.sentence_ChrF” function was utilized to compute segmental-level ChrF scores, which were then averaged [

28].

• METEOR (Metric for Evaluation of Translation with Explicit ORdering) evaluates translations based on synonymy, stemming, and word order.

• COMET is a neural-based evaluation metric that considers semantic adequacy and fluency [

29].

Table 2 was compiled based on an analysis of the reviewed scientific publications. It incorporates indicators drawn from these sources, and the final metric was approximately derived from the aggregated results [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

Table 2 summarizes the key evaluation metrics used to compare the performance of the selected translation models and explains how these results inform model selection.

3.3. Formatting of Mathematical Components

For the evaluation of the selected translation AI models, a parallel dataset was extracted from the OPUS repository, as presented in

Table 3. From this dataset, 1 000 Kazakh–Kyrgyz sentence pairs were selected. The Kyrgyz part of the corpus was treated as the gold reference, while the Kazakh sentences were used as the source for translation. An inspection of available resources [

15] revealed that there are several dozen datasets that include both Kazakh and Kyrgyz [

15]. As discussed in [

33], these data were utilized for the training of neural machine translation models, providing a foundation for evaluating model performance. However, only three of them are suitable for use in machine translation tasks shown in

Table 3.

To create a high-quality parallel corpus for a low-resource Kazakh-Kyrgyz pair, the first step involved selecting an existing monolingual Kazakh dataset consisting of approximately 300,000 sentences. The Kazakh corpus used in this study was obtained from an open-access dataset presented in [

34]. The original dataset consists of 302530 parallel sentence pairs in Kazakh and English. For the purposes of this research, only the Kazakh portion of the corpus was extracted and used as the source data for generating a Kazakh–Kyrgyz parallel corpus via machine translation.

3.4. AI Systems and Selecting Criteria

Several translation systems were considered for this task and evaluated according to a set of predefined criteria.

The selection criteria included (in order of importance):

Accessibility – the availability of the system for large-scale use, with preference for free or open access.

Translation quality – the linguistic accuracy and contextual relevance of the output.

Translation efficiency – the capability of the system to handle and translate large amounts of text.

Based on Internet searching results, the following translation systems were selected for comparison and evaluation: Google Translate, NLLB, ChatGPT, DeepSeek, Copilot and Gemma.

One of the most well-known and popular translation tools is Google Translate, which uses neural networks to train translation models based on large volumes of bilingual data. Since its launch in 2006, the system has greatly improved thanks to the use of Google Neural Machine Translation (GNMT), which introduced sequence models with deep neural network-based learning. Today, Google Translate supports over 100 languages and is one of the most widely used translation tools worldwide [

35].

NLLB (No Language Left Behind), developed by Meta, is a machine translation model designed to support a large number of languages, including rare and under-resourced ones. This is a significant achievement in the field of machine translation, as the model demonstrates excellent results in translating languages with limited training data. NLLB also employs deep learning and transformer-based approaches to improve translation quality [

37].

GPT (Generative Pretrained Transformer), developed by OpenAI, is one of the most successful examples of applying transformers in NLP. GPT is used not only for translation but also for a variety of other tasks, such as text generation, summarization, and dialogue systems. While GPT has shown good results in the context of natural language processing, its application for translation is limited and requires additional fine-tuning on specialized translation datasets to improve quality [

36].

DeepSeek is a machine translation system aimed at improving translation quality by applying more complex neural network architectures. An important aspect of DeepSeek's operation is the use of multitask learning to process different types of texts and increase the model's flexibility [

38].

Copilot, developed by GitHub and powered by OpenAI, is an artificial intelligence tool that helps developers write code. Copilot uses the OpenAI Codex model, which allows generating code in various programming languages based on text prompts. This can also be useful for translation tasks, where automating code generation can speed up the process of integrating translation into software systems. Copilot significantly boosts productivity by providing solutions to programming tasks in real-time [

39].

Gemma model is a family of lightweight, open-source large language models (LLMs) developed by Google. Introduced in March 2024, Gemma is based on the research and technology behind Google's Gemini models. Designed to be efficient and accessible, Gemma models are available in two sizes—2 billion and 7 billion parameters—and come with both pretrained and fine-tuned checkpoints [

40].

4. Results

4.1. Translation Quality Assessment Results by Various AI Systems

Table 4 presents the results obtained based on the evaluation metrics, providing an overview of the translation quality achieved by the selected AI system.

4.2. Selection of an AI System [Table with Quality Metrics Values+Paid System Rejection+Choosing Two Best Systems+Spead Tests + Final Selection of AI System]

As demonstrated in the comparison table, the Gemma model requires a significantly longer time to process the text body, whereas the NLLB model completes the same task in a substantially shorter period. Consequently, due to its higher efficiency and faster performance, the NLLB model was selected for further use.

4.3. Parameters of a Corpus Created

As shown in

Table 6, the resulting volume of parallel sentence pairs was stored in a single TSV file with a total size of 139.5 MB, containing approximately 10000000 words

4.4. Translation Errors and Their Correction

Table 7 presents examples of translation errors along with their descriptions.

During the manual verification process, several types of errors were identified, including semantic errors (incorrect translations of meanings) and lexical errors (missing or incorrectly translated words). The total number of identified semantic errors was 25584, of which 17680 were corrected. These corrections contributed to a significant improvement in the overall quality of the parallel corpus. As shown in

Table 6, the total number of words in the parallel corpus is approximately 10,000,000. Considering the linguistic similarity between Kazakh and Kyrgyz, it can be assumed that the Kyrgyz portion contains around 5,000,000 words. Based on the identified 25,584 translation errors, the estimated error rate is approximately

0.5%.

5. Discussion

The evaluation results clearly indicate that Chat GPT and DeepSeek are the most suitable models for the translation of Kazakh to Kyrgyz in

Table 4, based on their high performance across multiple metrics. Chat GPT stood out with superior results in COMET (0.818) and ChrF (31.56), indicating its ability to produce fluent and accurate translations. DeepSeek, while slightly behind Chat GPT, also showed competitive performance with a COMET score of 0.819 and a ChrF score of 31.56, making it another strong contender. In contrast, NLLB-200-3.3 and Gemma-2-27b performed adequately but fell short in comparison to the leading models. Their results suggest that while they can handle translation tasks, they may not provide the same accuracy and fluency required for high-quality corpus creation. Given these findings, Chat GPT and DeepSeek are identified as the most promising candidates for future research and the creation of a high-quality Kazakh-Kyrgyz parallel corpus. However, these systems do not provide free access suitable for processing large-scale datasets. Following them in terms of performance are the Gemma and NLLB models, both of which can be used via API. Among these, Gemma showed slightly more accurate translation results and was initially selected for further use. However, as demonstrated in

Table 7, Gemma required a relatively long time to process each sentence. Gemma requires, on average, 20 seconds to translate a single sentence. This means that translating a corpus of 302530 sentences would take approximately 2.5 months, which is a significantly long processing time. This estimate holds even when the model is run on a high-performance computer equipped with a powerful GPU and ample memory. Therefore, the NLLB model was chosen for translating the corpus, as it offered an optimal compromise between processing efficiency and translation quality.

The study focused on the automatic translation of sentences from Kazakh to Kyrgyz using the Nllb-200-3.3 model. The translation process was carried out on a high-performance computing system, which enabled the efficient processing of large volumes of data and the creation of a Kazakh-Kyrgyz parallel corpus. The results indicated a generally high quality of translation, particularly in standard syntactic constructions and commonly used expressions. However, several errors and inconsistencies were observed upon manual inspection of the translated output, revealing some of the limitations of the model when applied to closely related Turkic languages.

Table 6 presents additional examples of incorrect or inaccurate translations. One of the prominent issues was the incorrect handling of abbreviations. For example, the abbreviation “ҚР” (short for Қазақстан Республикасы, Republic of Kazakhstan) was occasionally mistranslated as “Кыргызстан” (Kyrgyzstan), “Кыргыз” (Kyrgyz), “Кыргыз Республикасы” (Republic of Kyrgyz), suggesting that the model may have incorrectly inferred meaning based on contextual frequency rather than semantic accuracy. This points to challenges in the model’s ability to distinguish between similar geopolitical terms within closely related languages. The NLLB model also struggles with the translation of abbreviated terms such as ЖШС (Жауапкершілігі шектеулі серіктестік), ҰБТ (Ұлттық Бірыңғай тест), and АҚ (Акциoнерлік Қoғам). In some cases, these abbreviations are omitted entirely, while in others, they are replaced with unrelated or inaccurate words, leading to a loss of meaning. In addition, there were instances where multiple Kazakh words were compressed into a single Kyrgyz word, leading to a loss of semantic content. For example, Kazakh sentences “қр премьер-министрі асқар маминнің төрағалығымен өткен үкімет oтырысында " еңбек " нәтижелі жұмыспен қамтуды және жаппай кәсіпкерлікті дамытудың 2017-2021 жылдарға арналған мемлекеттік бағдарламасын іске асыру барысы қаралды.” translated into Kyrgyz like this “Өкмөттүн жыйынында 2017-2021-жылдарга "эмгекти" натыйжалуу пайдалануу жана массалык ишкердикти өнүктүрүү бoюнча мамлекеттик прoграмманы ишке ашыруунун жүрүшү каралды.” As observed, the NLLB model misses the entire word form "қр премьер-министрі асқар маминнің төрағалығымен" and fails to translate it properly. Instead, it omits or provides inaccurate translations for such phrases, which leads to incomplete or incorrect translations. Such reductions compromise the quality of sentence alignment and the overall equivalence of meaning in the parallel corpus, which are critical for downstream tasks such as machine translation training and evaluation. Despite these challenges, the NLLB-200-3.3 model demonstrated potential for generating parallel data for low-resource language pairs within the Turkic family. However, to ensure a high-quality corpus, post-editing remains essential, particularly for domain-specific terms, abbreviations, and named entities. Moreover, it is recommended that the model be fine-tuned on dedicated Kazakh-Kyrgyz datasets to improve its accuracy and contextual understanding in future applications.

After manual verification and identification of translation errors, corrections were made wherever possible. As a result, the parallel sentences corpus has been significantly improved, with an overall quality increase based on the reduction of errors, making it more reliable for further research and practical applications. It is important to note that these errors were identified during the first round of verification, and additional rounds of checks will be conducted to identify and correct any remaining issues. As shown in

Table 5, the number of tokens decreased after translation, which is one aspect. On the other hand, lexical errors were identified, as seen in

Table 6, where certain words were either not translated at all or were translated using abbreviations.

6. Conclusions and Future Works

In this study, various AI systems for generating parallel corpus were explored, and the most suitable system was selected based on predefined criteria such as accessibility, translation quality, and efficiency. Using the chosen methodology, a parallel corpus of 302,530 sentence pairs was successfully created for the Kyrgyz-Kazakh language pair.

However, the generated corpus was not flawless; several translation errors were identified. The ratio of errors was quite small: 0.5% of all words in the developed corpus.

Future work will focus on correcting the remaining errors and improving the data. Additionally, the current methodology will be applied to expand the parallel corpus further, with the aim of supporting the development of more accurate and neural machine translation systems for low-resource Turkic languages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.A. and M.M.; methodology, U.T.; software, B.A.; validation, B.A., M.M. and U.A.; formal analysis, B.A.; investigation, U.T.; resources, B.A.; data curation, U.T.; writing—original draft preparation, B.A.; writing—review and editing, M.M. and U.T.; visualization, M.M.; supervision, U.T.; project administration, U.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded and financed by the grant project “Study of neural models for the formation of speech transcripts and minutes of meetings in Turkic languages” IRN AP23487816 of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cieri, C.; Maxwell, M.; Strassel, S.; Tracey, J. Selection Criteria for Low Resource Language Programs. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC'16), Portorož, Slovenia, 2016; European Language Resources Association (ELRA); pp. 4543–4549. [Google Scholar]

- Ivasubramanian, R.; Umamaheswari, T.; Babu, S.B.G.; Inakoti, R.; Salome, J. ; Y. M., Dr; Sivasubramanian, R. Natural Language Processing in Low-Resource Language Contexts. Front. Health Inform. 2024, 13, 1578–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakray, P.; Gelbukh, A.; Bandyopadhyay, S. Natural language processing applications for low-resource languages. Nat. Lang. Process. 2025, 31, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekarystankyzy, A.; Mamyrbayev, O.; Mendes, M.; Fazylzhanova, A.; Assam, M. Multilingual end-to-end ASR for low-resource Turkic languages with common alphabets. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tukeyev, U.; Amirova, D.; Karibayeva, A.; Sundetova, A.; Abduali, B. Combined Technology of Lexical Selection in Rule-Based Machine Translation. In Recent Advances in Systems, Control and Information Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukeyev, U.; Karibayeva, A.; Abduali, B. Neural Machine Translation System for the Kazakh Language Based on Synthetic Corpora. MATEC Web Conf. 2019, 252, 03006. [CrossRef]

- Karibayeva, B.Abduali, D. Amirova. Formation of the Synthetic Corpus for Kazakh on the Base of Endings Complete System. Turklang-2018 proceedings of international conference., 2018; pp.114-118.

- Ahmadnia, B.; Serrano, J.; Haffari, G. Persian-Spanish Low-Resource Statistical Machine Translation Through English as Pivot Language. Proceedings of Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing, RANLP 2017, Varna, Bulgaria, 2017; INCOMA Ltd; pp. 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Elmadani, K.N.; Buys, J. Neural Machine Translation between Low-Resource Languages with Synthetic Pivoting. Proceedings of LREC-COLING 2024, Torino, Italia, 2024; ELRA and ICCL; pp. 12144–12158. [Google Scholar]

- Pontes, J.J.A. Bilingual Sentence Alignment of a Parallel Corpus by Using English as a Pivot Language. Proceedings of JISIC, Quito, Ecuador, 2014; Association for Computational Linguistics; pp. 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Alekseev, A.; Turatali, T. KyrgyzNLP: Challenges, Progress, and Future. arXiv arXiv:2411.05503v1, 2024.

- Riemland, M. Theorizing Sustainable, Low-Resource MT in Development Settings: Pivot-Based MT between Guatemala’s Indigenous Mayan Languages. Transl. Spaces 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Murakami, Y.; Ishida, T. Towards Language Service Creation and Customization for Low-Resource Languages. Information 2020, 11, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trieu, H.-L.; Tran, V.; Ittoo, A.; Nguyen, L. Leveraging Additional Resources for Improving Statistical Machine Translation on Asian Low-Resource Languages. ACM Trans. Asian Low-Resour. Lang. Inf. Process. 2019, 18, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiedemann, J. Parallel Data, Tools and Interfaces in OPUS. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, LREC 2012; pp. 2214–2218. [Google Scholar]

- Karakanta, A.; Orrego-Carmona, D. Subtitling in Transition: The Case of TED Talks. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Koehn, P. Europarl: A Parallel Corpus for Statistical Machine Translation. Proceedings of Machine Translation Summit X, Phuket, Thailand; 2005; pp. 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Tiedemann, J.; Thottingal, S. OPUS-MT—Building Open Translation Services for the World. In Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Conference of the European Association for Machine Translation; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Balahur, A.; Turchi, M. Comparative Experiments Using Supervised Learning and Machine Translation for Multilingual Sentiment Analysis. Comput. Speech Lang. 2014, 28, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. arXiv arXiv:1409.0473, 2015.

- Koehn, P.; Knowles, R. Six Challenges for Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Neural Machine Translation; 2020; pp. 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Conneau, A.; Khandelwal, K.; Goyal, N.; Chaudhary, V.; Wenzek, G.; Guzmán, F.; Grave, E.; Ott, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. Unsupervised Cross-lingual Representation Learning at Scale. In Proceedings of the 58th ACL; 2020; pp. 8440–8451. [Google Scholar]

- Costa-jussà, M.R.; Cross, J.; et al. No Language Left Behind: Scaling Human-Centered Machine Translation. arXiv arXiv:2207.04672, 2022.

- Hou, X. Research on Translation Corpus Building with the Assistance of AI. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Smart Technologies and Systems for IoT; 2022; pp. 136–140. [Google Scholar]

- Reixa, I.D.; et al. Corpus PaGeS: A Multifunctional Resource for Language Learning, Translation and Cross-Linguistic Research. In Parallel Corpus for Contrastive and Translation Studies; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2019; pp. 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- Post, M. A Call for Clarity in Reporting BLEU Scores. In Proceedings of the Third Conference on Machine Translation; 2018; pp. 186–191. [Google Scholar]

- Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; Zhu, W.J. BLEU: A Method for Automatic Evaluation of Machine Translation. In Proceedings of ACL 2002, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Popović, M. chrF: Character n-gram F-score for Automatic MT Evaluation. In Proceedings of WMT 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rei, R.; Sánchez-Cartagena, V.; Popović, M. COMET: A Neural Framework for MT Evaluation. In Proceedings of EMNLP 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Tworek, J.; Jun, H.; Yuan, Q.; Ponde, H.B.; Kaplan, J.; Edwards, H.; Burda, Y.; Joseph, N.; Brockman, G.; et al. Evaluating Large Language Models Trained on Code. arXiv arXiv:2107.03374, 2021.

- Federmann, C.; Kocmi, T.; Xin, Y. NTREX-128—News Test References for MT Evaluation of 128 Languages. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Scaling Up Multilingual Evaluation; 2022; pp. 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, N.; Gao, C.; Chaudhary, V.; Chen, P.-J.; Wenzek, G.; Ju, D.; Krishnan, S.; Ranzato, M.; Guzman, F.; Fan, A. The FLORES-101 Evaluation Benchmark for Low-Resource and Multilingual Machine Translation. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2022, 10, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abduali, B.; Tukeyev, U.; Zhumanov, Z.; Israilova, N. Study of Kyrgyz-Kazakh Neural Machine Translation. In Recent Challenges in Intelligent Information and Database Systems; Nguyen, N.T., et al., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhumanov, Z.; et al. Integrated Technology for Creating Quality Parallel Corpus. In Advances in Computational Collective Intelligence; pp. 511–524.

- Wu, Y.; Schuster, M.; Chen, Z.; Le, Q.V.; Norouzi, M.; Macherey, W.; Krikun, M.; Cao, Y.; Gao, Q.; Macherey, K.; et al. Google’s Neural Machine Translation System: Bridging the Gap between Human and Machine Translation. arXiv arXiv:1609.08144, 2016.

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. arXiv arXiv:2005.14165, 2020.

- Costa-jussà, M.R.; Cross, J.; Fan, A.; Ghazvininejad, M.; Gu, J.; Gunasekara, C.; He, Y.; Kalbassi, E.; Liptchinsky, V.; Liu, Z.; et al. No Language Left Behind: Scaling Human-Centered Machine Translation. arXiv arXiv:2207.04672, 2022.

- Author(s). DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning. [Details missing].

- Ziegler, A.; Kalliamvakou, E.; Li, X.A.; Rice, A.; Rifkin, D.; Simister, S.; Sittampalam, G.; Aftandilian, E. Measuring GitHub Copilot’s Impact on Productivity. Commun. ACM 2024, 67, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemma Team; Mesnard, T.; et al. Gemma: Open Models Based on Gemini Research and Technology. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.08295.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).