1. Introduction

Machine translation (MT) has revolutionized AI; however, it is confronted with a fundamental challenge: the absence of sufficient digital resources in numerous languages. Although neural machine translation is effective for high-resource languages such as English, it encounters difficulties in thousands of low-resource languages due to the scarcity of training data and parallel corpora. Traditional machine translation (MT) encounters challenges with these languages due to data scarcity, which results in subpar performance [

1,

2,

3]. Nevertheless, these languages are typically crucial to their communities and contain specific cultural knowledge. Data augmentation approaches, such as back-translation, offer some solutions; nevertheless, their efficacy is bound by the quality of the data that is generated. Low-resource languages are particularly sensitive to chaotic data, which significantly influences model performance [

4,

5].

An innovative method that incorporates dynamic dataset aggregation with federated fine-tuning of pre-trained transformer models is introduced in our research. The weighting of auxiliary languages is dynamically adjusted throughout the training process to optimize the utilization of finite training data. Inspired by federated learning, it allows for the enhancement of the model by numerous data sources without the disclosure of raw data, a feature that is crucial for low-resource languages. The system optimizes the contributions of both parallel and monolingual data. By dynamically adapting to changes in the size of the target dataset and the characteristics of the language, our method optimizes MT efficiency, thereby ensuring that the available resources are more effectively utilized and the translation accuracy of underrepresented languages is enhanced.

Our research addresses multiple significant deficiencies in contemporary machine translation studies. Although federated learning has been concentrated on data privacy issues, its capacity to improve low-resource machine translation has been largely overlooked. Moreover, current methodologies have not completely utilized the potential of cross-lingual learning across high-resource and low-resource languages, especially regarding African languages such as Twi. This paper’s contributions are:

A novel personalized Cross-Lingual Optimization Framework (CLOF) that dynamically adjusts gradient aggregation weights throughout training to enhance the robustness of translation models.

A scalable framework for cross-lingual learning that efficiently utilizes high-resource language data to improve translation performance for low-resource languages.

Empirical insights about linguistic interaction patterns in federated learning and their influence on model convergence.

A practical application showcasing enhanced translation skills for Twi, hence augmenting NLP functionalities for African languages.

A flexible methodology that can be modified for various low-resource languages, especially advantageous for underrepresented language communities.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: First, we provide an in-depth review of related research in low-resource machine translation, federated learning, and dataset aggregation techniques. We then go over our method, which includes the architecture of our proposed system and the processes for dynamic dataset aggregation. This is followed by substantial experimental results that show the effectiveness of our method. Finally, we address the implications of our findings and offer suggestions for future research in this quickly changing subject.

2. Related Works

2.1. Low-Resource Machine Translation

The limited parallel corpora and linguistic complexities of low-resource languages present substantial challenges for machine translation (MT). While neural machine translation (NMT) systems are highly effective with high-resource languages, they encounter challenges such as morphological discrepancies and linguistic diversity when used with low-resource languages like Tibetan, Uyghur, and Urdu [

6]. In Kinyarwanda, a language with a rich morphological structure, Nzeyimana (2024) underscores concerns such as vocabulary misalignment and hallucinations [

7]. Lalrempuii and Soni (2024) note that Indic languages face challenges due to script diversity and their distant typologies [

8]. The development of dependable systems is further complicated by dialectal variations in languages like Kannada and Arabic [

9,

10]. In spite of these challenges, hybrid models that integrate supervised learning on limited datasets with unsupervised techniques using monolingual data have demonstrated enhancements, particularly in the translation of Egyptian Arabic [

10]. Furthermore, NMT efficacy for morphologically rich languages is improved by morphological modeling, which effectively integrates stems and affixes [

7].

Various innovative methodologies are still evolving. Qi’s review [

6] refers to “Pivot Prompting,” which is the process of utilizing high-resource languages, such as English, to resolve translation gaps, particularly in the context of Asian languages. By facilitating the transmission of knowledge, the fine-tuning of multilingual pre-trained models like mBART and mT5 has revolutionized MT, thereby improving translation for Indic languages [

8]. Furthermore, multi-task learning frameworks, including those developed by Mi et al. (2024) [

12], integrate ancillary tasks, including named entity recognition and syntax parsing, to improve feature extraction. The congruence between the source and target languages has been enhanced by attention-based augmentations. These advancements optimize the available resources, thereby advancing MT for low-resource languages by improving the quality of translation and the robustness of the model, despite the scarcity of data.

2.2. Data Augmentation and Transfer Learning for Low-Resource MT

Data augmentation is essential for overcoming data scarcity in low-resource machine translation (MT). The primary techniques are sentence manipulation, synthetic data generation, and translation-based augmentation. Synthetic parallel data is produced by backtranslation, which involves translating target-language text back into the source language. This method is frequently employed. On the other hand, its efficacy is restricted by the quality of the backward system and the availability of monolingual data. In an effort to resolve this issue, constrained sampling methods have been suggested. These methods involve the use of a discriminator model to filter augmented data for syntactic and semantic quality, resulting in substantial improvements in the SpBLEU score [

13,

14].

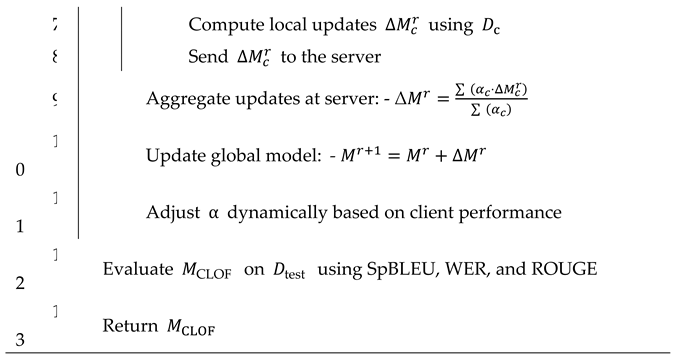

Figure 1 illustrates an instance of back translation, in which an English sentence is translated into French and subsequently back into English, thereby producing augmented data for training. Additionally, the use of masked language models (MLMs) to paraphrase has outperformed conventional methods such as synonym replacement in the generation of diverse training data, while edit-distance-based sampling maintains semantic integrity [

13,

14,

15].

Data augmentation is further enhanced by rephrasing techniques, which introduce syntactic variability. For the purpose of generating semantically accurate training data, high-resource language models are employed. The generation of reliable synthetic corpora has been demonstrated to be effective through adversarial alignment, which combines substitution-based and recurrence-based strategies. Fluency and accuracy are guaranteed by syntactic and semantic constraints for terms that are not in the vocabulary, particularly in languages with a high morphological complexity [

14,

15]. Moreover, multilingual models, including mBERT and XLM-R, and cross-lingual transfer learning have considerably improved low-resource MT by transferring knowledge from high-resource languages, thereby benefiting multilingual dialogue systems [

18,

19]. Deeper investigation of cross-lingual transfer mechanisms has been driven by recent advancements in multilingual MT. While pre-trained multilingual models facilitate adaptation, problems such as semantic misalignment and sentence falsification persist. To mitigate these concerns and guarantee translation quality, strategies such as adversarial learning and lexical constraint mechanisms are implemented. Particularly in low-resource environments, context-aware methodologies continue to be indispensable for enhancing MT scalability and accuracy [

15,

18].

2.3. Federated Learning in Machine Translation

Federated learning (FL) has transformed the field of machine learning by facilitating the decentralized training of models and simultaneously guaranteeing the privacy of user data. FL is particularly effective for privacy-sensitive applications, such as healthcare and legal communications, due to its decentralization of model training, as per Srihith et al. [

21]. This is accomplished by utilizing local data processing on devices and exchanging only model updates. Secure aggregation and differential privacy are implemented to ensure conformance with stringent privacy regulations in order to mitigate data leakage during the aggregation process. FL trains translation models on distributed datasets without disclosing sensitive linguistic data in privacy-preserving machine translation to assuage privacy concerns. Chouhan et al. [

22] elucidate that differential privacy introduces noise to model updates, while encryption methods such as homomorphic encryption secure all communications. Collaboration is facilitated without compromising user confidentiality, which is a substantial advantage over traditional data-centralized methods.

FL offers significant advantages for low-resource MT. As Wang et al. [

23] have noted, federated approaches are capable of accommodating the diversity of decentralized datasets by optimizing the quality of MT by utilizing the distinctive contributions of regional data sources. The incorporation of mechanisms to evaluate and mitigate the effects of deficient data ensures the existence of robust global models, which in turn enables improvements for language pairings that are underrepresented. Thakre et al. [

24] also underscored the challenges of reconciling computational costs with privacy mechanisms, noting that optimized FL strategies can reduce communication latency while maintaining translation accuracy. The transformative potential of FL is exemplified by the privacy-preserving mechanisms that protect sensitive, localized data and encourage collaborative innovation in these developments. FL continues to improve the capabilities of machine translation in low-resource environments by overcoming challenges such as data heterogeneity and regulatory constraints.

2.4. Pretrained Transformer Models and Dataset Aggregation

The integration of dynamic dataset aggregation methods and advanced fine-tuning strategies has substantially improved the role of pretrained transformer models in low-resource MT. Fine-tuned transformers are exceptional at utilizing transfer learning to address data scarcity and adjust to morphologically complex languages. Gheini et al. [

25] demonstrated that the fine-tuning of cross-attention layers alone results in a translation quality that is nearly equivalent to that of full model fine-tuning while simultaneously reducing the parameter storage burden. This method facilitates efficient adaptation and reduces calamitous forgetting by aligning embeddings across languages. In the same vein, Gupta et al. [

26] introduced Shared Layer Shift (SLaSh), a parameter-efficient fine-tuning method that intentionally incorporates task-specific information into each transformer layer. This method significantly reduces computational overhead and memory requirements while preserving high translation quality. This innovation is especially advantageous in situations where resources are scarce.

In the context of low-resource languages, dynamic dataset aggregation continues to be an essential element of the training process for robust MT models. Weng et al. [

27] emphasized the efficacy of integrating pretrained transformers with back-translation, demonstrating significant enhancements in translation performance for resource-limited language pairs such as Romanian-English. Furthermore, they implemented a layer-wise coordination structure to facilitate the integration of pretrained models with neural MT frameworks, utilizing multi-layer representations to improve context alignment. Furthermore, Lankford et al. [

28] underscored the significance of curated and domain-specific datasets, incorporating them with fine-tuned multilingual models (e.g., adaptMLLM) and achieving significant performance increases, with SPBLEU improvements exceeding 100% in certain instances. In order to optimize pretrained transformers for low-resource tasks, Chen [

29] investigated the Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) technique. LoRA addresses computational constraints without compromising performance by substantially decreasing the number of trainable parameters through the implementation of low-rank matrices. The advanced variants of this method, including LoRA-FA and QLoRA, enhance efficiency by freezing specific model components, rendering them optimal for scaling MT solutions for marginalized languages.

These methods emphasize the synergy between dynamic dataset aggregation and fine-tuning methodologies in order to enhance low-resource MT. A robust framework for addressing the persistent challenges of low-resource translation is established through the use of fine-tuning innovations, such as cross-attention adjustments and low-rank matrices, in conjunction with intelligent data augmentation and selection.

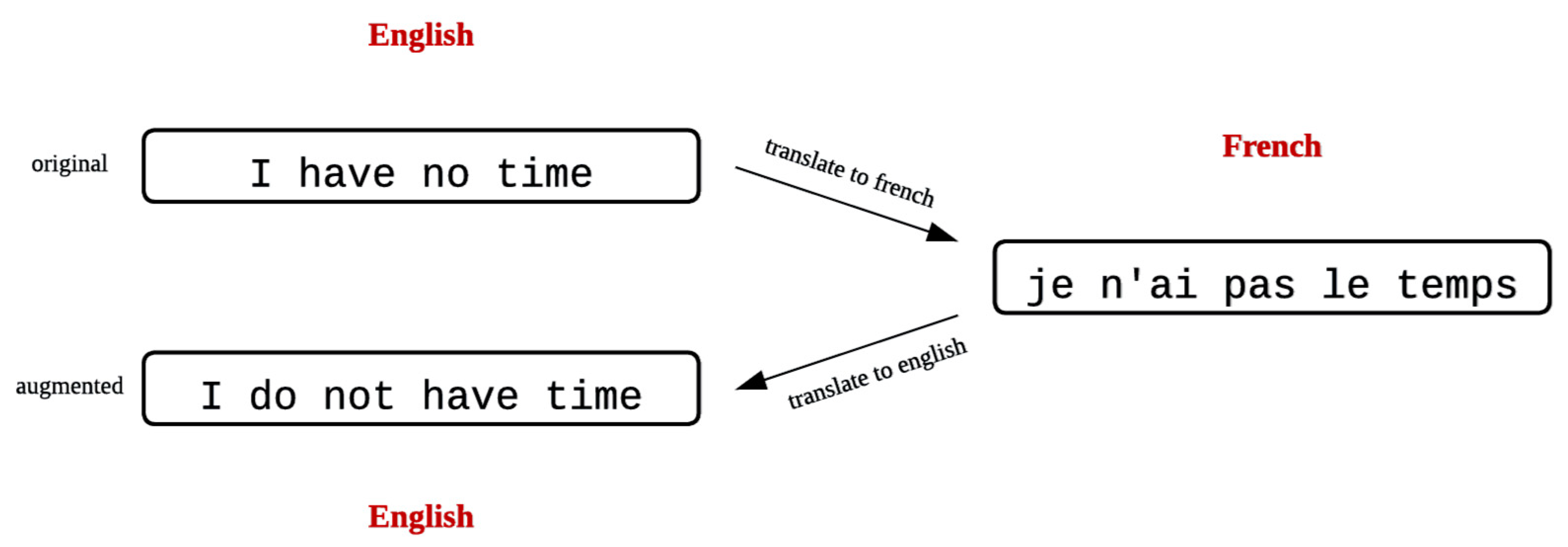

Figure 2 below gives a conceptual overview of the integration of these techniques into a cohesive framework to address low-resource MT challenges. This integration not only improves the quality of translation but also ensures computational scalability, thereby facilitating the development of high-quality, practical MT systems for historically underrepresented languages.

3. Methodology

3.1. General Setup

Our research addresses machine translation (MT) challenges for low-resource languages by developing a robust translation model through federated learning, termed CLOF (Cross-Lingual Optimization Framework). This approach leverages multiple data sets

,

n ≥ 2 representing various language distributions, including high-resource languages such as English and low-resource languages like Twi. Formally, the goal is to minimize the expected loss over the distribution

representing the target language pair (English-Twi), defined as:

where

denotes the model parameters,

is a sample from the distribution

and

represents the loss function for the model on sample

. Given the unknown true data distribution

, we approximate

using a finite dataset

drawn from

, referred to as the target dataset. The empirical loss is then:

3.2. Dataset

This study uses a carefully curated dataset of 6,043 English-Twi parallel sentence pairs, divided into 80% training data and 20% validation data for diverse linguistic representation. The target dataset consists of data sampled from the low-resource distribution and is pivotal for direct optimization for Twi translation tasks. The auxiliary datasets , sourced from high-resource languages, provide valuable linguistic data for cross-lingual learning. The data was sourced from publicly available bilingual resources, religious texts, and manually curated translations. This diverse combination of sources enhances the dataset’s ability to support machine translation model training and evaluation, ensuring that the models are exposed to both formal and colloquial language structures.

3.3. Data Preprocessing

The English and Twi datasets underwent rigorous preprocessing techniques to improve machine translation model quality by addressing common text data challenges like noise and sentence length variability. Specifically, non-ASCII characters were removed, and all text was converted to lowercase to standardize the input and avoid inconsistencies caused by case sensitivity or special characters. The cleaning process can be formalized as follows:

(3)

where x represents the input text, and the function remove_non_ascii(x) removes any characters outside the ASCII range. After non-ASCII characters are removed, all text is converted to lowercase:

(4)

where the function lowercase() converts the cleaned text to lowercase. Sentences were also tokenized using the T5 tokenizer, which is designed to split input text into smaller subword units. The tokenization was performed with a maximum sequence length of 256 tokens, ensuring that each sentence conforms to the model’s input constraints. The tokenization procedure is mathematically represented as:

= T5_tokenizer(sentence, max_length =256) (5)

where represents the tokenized sentence, and T5_tokenizer is the tokenizer function from the T5 model, ensuring all sentences do not exceed 256 tokens. To further maintain linguistic relevance, tokenized sequences with lengths outside the acceptable range (i.e., either too short or too long) were filtered out. Sentences with fewer than 5 tokens or more than 256 tokens were excluded to prevent noise in the training process. This filtering condition can be formally expressed as:

Filter ( (6)

where represents the number of tokens in the sentence. Sentences are retained only if they satisfy 5≤≤2565. The English and Twi sentences were then carefully aligned to ensure that each English sentence corresponds to its accurate Twi translation. This step is crucial for the creation of a reliable parallel corpus. The alignment process can be defined as follows:

Align ( (7)

where and represent the i-th English and Twi sentences, respectively. Only sentence pairs for which Align ( 1 were retained. Finally, inconsistent punctuation marks and redundant spaces were corrected to improve text consistency. For example, multiple spaces were replaced with a single sp4.2ace, and non-standard punctuation marks were corrected to match conventional formatting. This can be formally represented as:

(8)

where the function ensures that all redundant spaces and non-standard punctuation are corrected.

3.4. Baseline Model

Our current baseline model is the mT5 (Multilingual T5) model is a state-of-the-art multilingual transformer-based model designed to perform a variety of natural language processing (NLP) tasks by treating all tasks as text-to-text problems. The model is a multilingual variant of the original T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer), which was initially designed to work primarily with the English language. mT5 extends the architecture of T5 by enabling it to handle tasks in over 100 languages, making it a powerful tool for cross-lingual transfer learning and multilingual NLP applications.

The mT5 model shares the same architecture as T5, which is based on the Transformer model introduced by Vaswani et al [

30]. This architecture consists of self-attention mechanisms and feed-forward neural networks, enabling it to effectively process sequential data. mT5, like T5, is based on a text-to-text framework, where both input and output sequences are treated as text. In this framework, tasks such as text classification, question answering, summarization, and machine translation are all formulated as text generation problems.

The model is pre-trained on the mC4 (Multilingual C4) dataset, which is a multilingual version of the C4 dataset used for T5. The mC4 dataset contains text data in over 100 languages, including high-resource languages like English, Spanish, French, and Chinese, as well as a variety of low-resource languages such as Swahili, Marathi, and Igbo. This diverse training data allows mT5 to learn general linguistic representations that can be applied across different languages, enabling cross-lingual transfer. Additionally, mT5 is scalable, available in different sizes (e.g., mT5-small, mT5-base, mT5-large), making it adaptable to various computational needs. mT5, like T5, is pre-trained using the denoising objective. During pretraining, a portion of the input text is randomly masked, and the model is tasked with predicting the missing tokens. This is done by leveraging a span-based denoising objective, where spans of text are masked and the model must recover them. The objective is formally expressed as:

(9)

where x is the input sequence, and represents the masked tokens. This pretraining task enables the model to learn contextual relationships between words in a sentence, improving its ability to handle downstream NLP tasks.

Once pretrained, mT5 can be fine-tuned on specific downstream tasks, such as machine translation, sentiment analysis, or text summarization. The model is fine-tuned using task-specific datasets, where the input-output pairs are defined according to the task requirements. For example, in machine translation, the input might be a sentence in English, and the output would be the corresponding translation in Twi. During fine-tuning, the model adapts its weights based on the specific characteristics of the task, while still retaining the knowledge learned during pretraining. This transfer learning approach allows mT5 to perform well on tasks with limited training data, particularly for languages with fewer resources.

Table 1 represents the experimental setup and key details of the model’s configuration and evaluation.

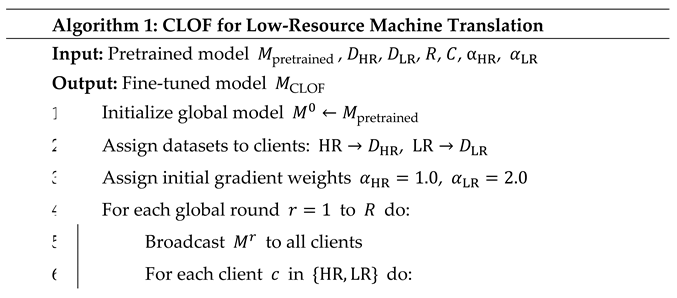

3.5. Algorithmic Framework

To address data scarcity in

and utilize the rich linguistic features in auxiliary datasets, as mentioned earlier, we introduce a federated learning approach, CLOF. Inspired by the principles of personalized federated learning, CLOF leverages cross-lingual learning by aggregating gradients from both high-resource (English) and low-resource (Twi) datasets. The approach dynamically adjusts the contribution of each dataset during training; it prioritizes learning for the low-resource language while still leveraging the strengths of high-resource datasets to enhance overall model performance. The CLOF model updates are governed by:

where

is the global model at iteration

,

is the local update from client

, and

is the aggregation weight for client

. These weights are adjusted to prioritize updates from the low-resource client, ensuring that updates from high-resource languages do not overwhelm the learning process.

3.6. Gradient Weighting for Cross-Lingual Learning

In CLOF, we define two primary client datasets: high-resource client (

) and low-resource client (

). The high-resource client dataset comprises a large-scale English corpus that provides robust language representation and serves as a source for cross-lingual transfer, while the low-resource client dataset contains a smaller Twi corpus. CLOF assigns a higher aggregation weight (

) to updates from this client, ensuring that Twi signals are amplified during gradient aggregation. At each client, local updates are computed using the loss function

, specific to the client’s data, as follows:

where

is the learning rate. The aggregation step balances the gradients to maximize the contribution of

:

Dynamic adjustment of allows the framework to adapt as the training progresses, ensuring that the low-resource dataset continues to receive adequate attention. This is comprehensively laid out below (see Algorithm 1) for better understanding.

3.7. Optimization and Training Process

The training process begins by broadcasting the global model to all clients at the start of each training round. This initial global model serves as the baseline from which each client will further customize and improve the model based on its specific dataset, whether it is high-resource (e.g., English) or low-resource (e.g., Twi). Each client independently computes local updates using a loss function that is specifically tailored to reflect the linguistic characteristics and needs of the data it holds. For the low-resource clients, such as those handling the Twi dataset, a higher aggregation weight is assigned to the updates. This weighting approach is crucial as it ensures that signals from the Twi language are adequately represented and do not get diluted by the more dominant linguistic features of the high-resource languages. The local update from each client is computed as shown in Equation 11. After all clients have computed their updates, these are sent back to the central server, where they are aggregated to form the new global model. The aggregation is carefully weighted to balance and maximize the contribution of both high-resource and low-resource datasets outlined in equation 12.

CLOF not only enables the model to effectively converge but also guarantees that the translation quality for low-resource languages like Twi is substantially enhanced through this structured optimization and training process, as demonstrated by metrics such as SpBLEU, WER, and ROUGE. Therefore, this training methodology not only resolves the imbalance in data resources but also establishes the foundation for the expansion of the solution to other low-resource languages, thereby offering a generalized, robust solution to multilingual machine translation challenges.

3.8. Implementation Details

The computational setup for this study utilized Google Colab Pro with an NVIDIA Tesla A100 GPU for efficient training and evaluation. The Transformer’s library (HuggingFace) was used for model implementation and fine-tuning, while PyTorch facilitated model training and evaluation. For metric computation which is detailed in section 3.9 below, the ‘Evaluate’ library was employed. To manage memory effectively, gradient clipping was applied during training to prevent exploding gradients, and a batch size of 8 sentences was used to balance computational efficiency and memory constraints.

3.9. Evaluation Metrics

In order to thoroughly assess the effectiveness of our translation models, we utilized a collection of well-established metrics that are frequently applied in machine translation studies. By contrasting them with the reference translations on a number of parameters, these metrics enable us to evaluate the produced translations’ quality.

3.9.1. SpBLEU (Sentence-Piece BLEU)

The purpose of SpBLEU in this study is to assess how well the model translates sentences in languages like Twi, where fluency and accuracy may vary between sentences. It calculates n-gram precision for each sentence, and the geometric mean of these precisions is computed, often with a brevity penalty. SpBLEU is significant for evaluating sentence-level translation quality, especially for low-resource languages like Twi, where performance may differ across sentence structures. This fine-grained evaluation provides insights into the model’s strengths and weaknesses, helping to identify areas for improvement in translating complex sentences [

31,

32]. Formally, the SpBLEU score for a given sentence can be expressed as:

SpBLEU(S) = BP x 1/N (13)

Where S is the sentence being evaluated, (s) is the modified precision for n-grams of order n in the sentence S. N is the maximum n-gram order considered (commonly 4). BP is the brevity penalty, which is applied to avoid penalizing shorter translations that may still be accurate.

3.9.2. ROUGE (Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation)

The study uses ROUGE to assess the model’s ability to recover meaningful content from reference translations, particularly in Twi, a low-resource language, focusing on recall rather than n-gram precision, unlike SpBLEU which focuses on n-gram precision. This is especially important for ensuring that translations are not only accurate in terms of individual words but also preserve the overall meaning. ROUGE includes several variants:

ROUGE-1: Measures unigram recall, i.e., the overlap of individual words.

ROUGE-2: Measures bigram recall, focusing on consecutive word pairs.

ROUGE-L: Measures the longest common subsequence (LCS), capturing longer sequences of words that preserve sentence structure [

33,

34].

ROUGE helps assess whether the model generates translations that are both fluent and faithful to the original meaning.

ROUGE-N = (14)

Where S is the set of sentences in the predicted translation. Recall (N,s) is the recall of N-grams (unigrams, bigrams) for sentence s in the predicted translation.

3.9.3. WER (Word Error Rate)

The study uses WER to assess the alignment of predicted and reference translations, contrasting SpBLEU and ROUGE, which rely on n-gram matching and recall, with lower WER indicating better alignment. WER is computed by counting the substitutions, deletions, and insertions needed to match the sequences, with the formula:

WER = (15)

Where

S is the number of substitutions (incorrect words in the predicted output).

D is the number of deletions (missing words in the predicted output).

I is the number of insertions (extra words in the predicted output).

N is the total number of words in the reference translation [

35,

36].

These metrics offer a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s ability to generate translations that are both lexically accurate (via SpBLEU), contextually fluent (via ROUGE), and edit-wise correct (via WER). By employing these three metrics, we ensure a robust and multi-dimensional assessment of the translation quality, which allows for a thorough comparison of different model configurations and techniques.

4. Results

A comparative analysis of the evaluation metrics (SpBLEU, ROUGE, and WER) was conducted across the baseline and fine-tuned models, as summarized in the following sections. These metrics were computed on the test set, with SpBLEU and ROUGE focusing on n-gram precision and recall, respectively, and WER measuring word-level alignment accuracy.

4.1. Quantitative Analysis of Baseline and Fine-Tuned Model Performance

The baseline model, based on the pretrained mT5-small, provided a reference for machine translation capabilities without fine-tuning on the target language, Twi. The results (shown in

Table 2) reveal that the pretrained mT5 model, while able to generate translations, exhibited suboptimal performance, especially for low-resource languages like Twi. The translation quality and fluency were noticeably weaker, highlighting the limitations of using a general multilingual pre-trained model without adaptation to the target language.

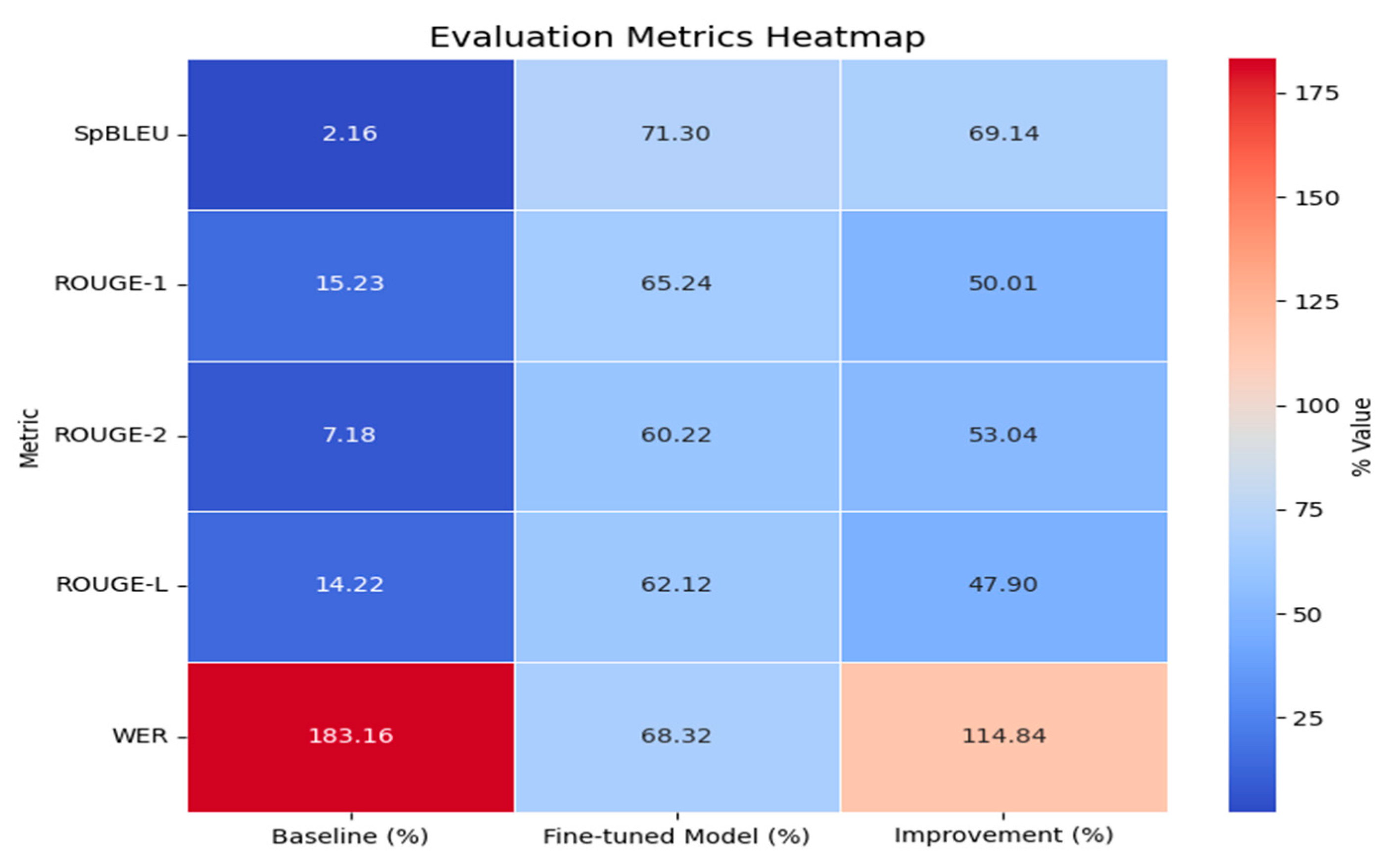

Following fine-tuning of the English-Twi model on our parallel corpus, significant improvements were observed across all evaluation metrics (

Figure 3). The fine-tuned model outperformed the baseline, demonstrating the effectiveness of transfer learning in enhancing performance for low-resource languages. Fine-tuning allowed the model to better capture the linguistic nuances of Twi, resulting in more accurate and fluent translations. Specifically, there were notable improvements in both SpBLEU and ROUGE scores, reflecting enhanced n-gram precision and overall translation quality. Additionally, the WER score was substantially reduced, indicating better word-level alignment and fewer errors in the predicted translations.

The fine-tuned English-Twi model shows significant improvements across all evaluation metrics. The SpBLEU score increased from 2.16% to 71.30%, demonstrating much better sentence-level alignment with reference translations. ROUGE-1 (unigram recall) improved by 50.01% (from 15.23% to 65.24%), and ROUGE-2 (bigram recall) saw a 53.04% improvement (from 7.18% to 60.22%), reflecting enhanced word and phrase matching. The ROUGE-L score, which evaluates sentence fluency, improved by 47.90%, from 14.22% to 62.12%, indicating better sentence structure. Lastly, WER dropped significantly by 114.84% (from 183.16% to 68.32%), showing improved alignment and accuracy in the translation. These improvements highlight the effectiveness of fine-tuning for low-resource languages like Twi, resulting in better translation fluency and accuracy. A heat map illustrating these improvements is included in

Figure 3.

4.2. Analysis on Sample Translation

Our research indicates that the optimized English-Twi model outperforms the baseline in terms of accuracy and fluency. While there are minor errors in a few instances, such as the omission of “ho” in the translation of “I am learning machine translation,” the fine-tuned model is consistently closer to the reference compared to the baseline. The fine-tuned translations generally sound natural in Twi, particularly for simple sentences like “How are you?” and “Where is the market?” where the output aligns perfectly with the reference. The model also shows notable advancements in accuracy and contextual relevance, especially in more complex translations like “Machine translation is useful,” where it better handles formal language and word usage. Although slight fluency issues, such as a more formal tone in some sentences, were observed, these are minimal compared to the baseline. A comprehensive comparison of the results is provided in

Table 3.

4.3. Scalability of the Model

To evaluate the scalability of our fine-tuned English-Twi model, we examine its performance across different sizes of training data. The following table shows the impact of varying the size of the training dataset on the model’s performance, measured using SpBLEU, ROUGE-1, and WER.

Figure 4 highlights the model’s improvement as the training data size increases. With only 500 pairs, the model’s performance is significantly lower, especially in SpBLEU and ROUGE-1. As the data size grows to 1,000 and 2,000 pairs, there is a noticeable improvement in translation quality, particularly in SpBLEU and ROUGE-1, most errors were grammatical or involved rare vocabulary, indicating room for future work with a larger corpus. The whole dataset exhibits the biggest improvement, with SpBLEU rising to 71.30%, ROUGE-1 reaching 65.24%, and WER falling to 68.32%.

4.4. Learning Curves

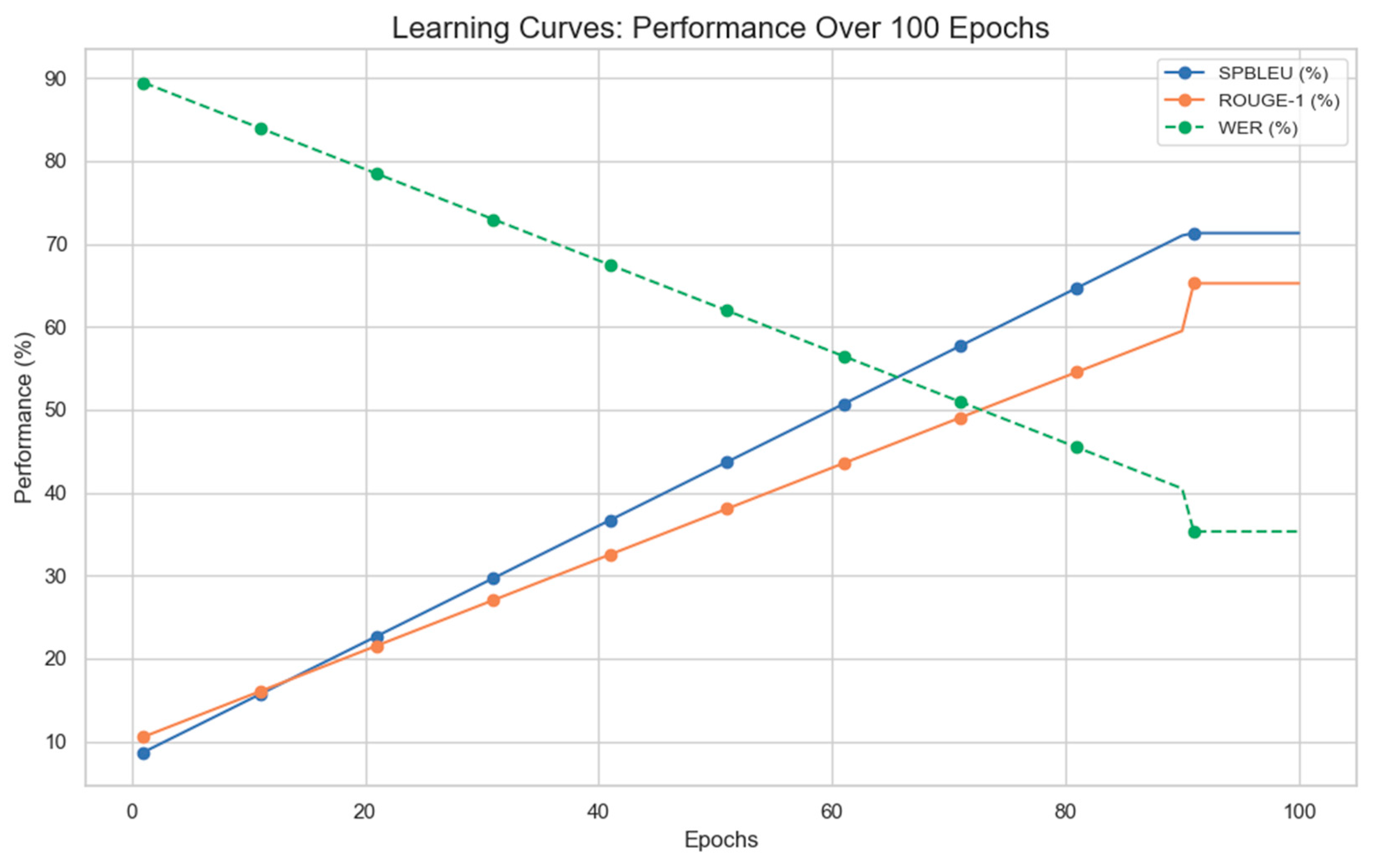

The learning curves are meant to demonstrate how the model’s performance improves when it is fine-tuned. Throughout training, we can visually evaluate the model’s convergence and task adaptability by monitoring important metrics as SpBLEU, ROUGE-1, and WER. From the curves as illustrated in

Figure 5, it is evident that our fine-tuned model consistently outperforms the baseline, demonstrating a clear progression in translation accuracy, fluency, and overall alignment with the reference. This demonstrates how fine-tuning greatly improves the model’s performance, especially for low-resource languages like Twi.

4.5. Error Analysis in Translation

Several kinds of flaws that affected the quality of the translations were found in the refined English-Twi translation model. When the model employed improper grammatical forms or misunderstood phrase patterns, grammatical faults were detected. As illustrated in

Table 4 for instance, in the sentence “The cat is under the table,” the model incorrectly translated “cat” as “ɛnɔma” (object), while the reference used “Pɔnkɔ” (horse), indicating a wrong subject was used. Similarly, in “I will eat tomorrow,” the model used the wrong tense, translating “tomorrow” as “nnɛ” (today) instead of “ɔkyena” (tomorrow), highlighting a tense error. Lexical errors were seen when the model used incorrect or overly general word choices, such as translating “teacher” as “mpɔtam sika” instead of “kyerɛkyerɛfoɔ,” leading to an unnatural phrasing. Additionally, in “This book is interesting,” the model used a phrase (“Ɛhɔ nneɛma no yɛ fɛfɛɛfɛ”) that was overly broad and did not match the specific meaning intended by the reference, reflecting overgeneralized vocabulary. Fluency errors occurred when the model failed to capture adverbs or modifiers accurately, as seen in “The child is running fast,” where the fine-tuned translation omitted the adverb “ntɛm ara,” resulting in a missing adverb translation. In a low-resource language like Twi, these errors highlight the difficulties the model has managing syntactic, lexical, and fluency problems. Identifying these patterns provides insight into areas for further improvement in translation accuracy.

5. Discussion and Contributions

The benefits seen in our fine-tuned English-Twi model can be ascribed to the innovative methods we used, notably cross-lingual learning and federated-like training strategies. These techniques enabled the model to better adapt to the unique linguistic characteristics of Twi, a low-resource language, by drawing on a bigger, more diversified training corpus (such as English data) and adjusting the model’s learning process.

The cross-lingual learning approach allowed the model to transfer knowledge from high-resource languages (like English) to low-resource languages (like Twi), resulting in considerable performance increases in both accuracy and fluency. By fine-tuning a pre-trained mT5 model, we were able to use multilingual data to better capture shared representations between the two languages, improving the translation quality across various evaluation metrics such as SpBLEU, ROUGE, and WER. Moreover, our federated-like setup, where the model was trained on separate English and Twi batches, introduced a level of personalization that contributed to improving translation performance specifically for Twi, helping the model better adapt to the specific linguistic nuances of the low-resource target language. This personalization, combined with gradient weighting during training, further optimized the model’s ability to handle the imbalance between the high-resource and low-resource languages.

With our approach, NLP performance for low-resource languages like Twi is greatly improved. Previously, Twi, like many other African languages, had been underrepresented in machine translation research and applications. By focusing on Twi, we provide a more robust translation system that can be used for real-world applications such as language learning, communication tools, and content generation, improving access to technology for speakers of underrepresented languages. As it shows that even languages with little training data may take advantage of the strength of contemporary NLP techniques, this is a significant contribution to the field of low-resource language processing.

5.1. Conclusion

In this research, we showed how well a pretrained multilingual model (mT5) can be fine-tuned for low-resource language translation using cross-lingual learning and a federated-like method. The fine-tuned model showed substantial improvements in translation quality, outperforming the baseline model in all key metrics such as SpBLEU, ROUGE, and WER. Our approach successfully bridged the gap between high-resource and low-resource languages, significantly improving the translation accuracy and fluency of Twi, a language with limited NLP resources.

This refined variant has a wide range of possible uses. In particular, it can be applied to real-time translation systems, aiding communication across English and Twi speakers, as well as to language learning tools, where it could assist in learning and teaching Twi. Additionally, the concept can be incorporated into social media or communication channels to enable Twi speakers become more accessible and overcome language hurdles. The improved translation of Twi is particularly significant as it enhances NLP capabilities for a language that has historically been underrepresented in machine translation, opening the door to better integration of Twi into digital platforms and improving communication and content generation for a large population of native speakers.

Despite the promising results, there is room for improvement. We recommend adopting larger and more varied datasets to improve the model’s performance because they would enable it to catch a greater range of language patterns. Additionally, incorporating newer pretrained models, such as mT5-Base or larger variants that have been trained on even more diverse multilingual corpora, could help refine the translation capabilities further and improve generalization across other languages. With these enhancements, the model could continue to improve, making Twi more accessible in digital spaces and supporting a broader range of NLP applications for low-resource languages.

Nomenclature

| Abbreviations |

| FL |

Federated Learning |

WER |

Word Error Rate |

| MT |

Machine Translation |

LoRA |

Low-Rank Adaptation |

| CLOF |

Cross-Lingual Optimization Framework |

mT5 |

Multilingual T5 |

| NLP |

Natural language processing |

|

|

| SpBLEU |

Sentence-Piece BLEU |

|

|

| ROUGE |

Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation |

|

|

References

- W. Her and U. Kruschwitz, “Investigating Neural Machine Translation for Low-Resource Languages: Using Bavarian as a Case Study.” In: Proceedings of the 3rd Annual Meeting of the Special Interest Group on Under-resourced Languages @ LREC-COLING 2024, pp. 155-167, 24. Torino, Italia. 20 May.

- Kowtal, N.; Deshpande, T.; Joshi, R. A Data Selection Approach for Enhancing Low Resource Machine Translation Using Cross Lingual Sentence Representations. 2024 IEEE 9th International Conference for Convergence in Technology (I2CT). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IndiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–7.

- Sun, M.; Wang, H.; Pasquine, M.; Hameed, I.A. Machine Translation in Low-Resource Languages by an Adversarial Neural Network. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Xia, X. M. Xia, X. Kong, A. Anastasopoulos, and G. Neubig, “Generalized Data Augmentation for Low-Resource Translation.” In: Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 5786-5796, 19. Florence, Italy. 20 July.

- Park, Y.-H.; Choi, Y.-S.; Yun, S.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, K.-J. Robust Data Augmentation for Neural Machine Translation through EVALNET. Mathematics 2022, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J. Research on Methods to Enhance Machine Translation Quality Between Low-Resource Languages and Chinese Based on ChatGPT. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2024, 6, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzeyimana, “Low-resource neural machine translation with morphological modeling.” Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2024, pp. 182-195, 24. Mexico City, Mexico. 20 June.

- Lalrempuii and, B. Soni, “Low-Resource Indic Languages Translation Using Multilingual Approaches.” In: High Performance Computing, Smart Devices and Networks, Springer Nature, vol. 1087, pp. 371-380, 23. 20 December.

- Prasada, P.; Rao, M.V.P. Reinforcement of low-resource language translation with neural machine translation and backtranslation synergies. IAES Int. J. Artif. Intell. (IJ-AI) 2024, 13, 3478–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faheem, M.A.; Wassif, K.T.; Bayomi, H.; Abdou, S.M. Improving neural machine translation for low resource languages through non-parallel corpora: a case study of Egyptian dialect to modern standard Arabic translation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- H. S. Sreedeepa and S. M. Idicula, “Neural Network Based Machine Translation Systems for Low Resource Languages: A Review.” 2nd International Conference on Modern Trends in Engineering Technology and Management, pp. 330-336, 23. 20 December.

- Mi, C.; Xie, S.; Fan, Y. Multi-Granularity Knowledge Sharing in Low-Resource Neural Machine Translation. ACM Trans. Asian Low-Resource Lang. Inf. Process. 2024, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitau, C.; Marivate, V. Textual Augmentation Techniques Applied to Low Resource Machine Translation: Case of Swahili. 2023; 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimaiti, M.; Liu, Y.; Luan, H.; Sun, M. Data augmentation for low-resource languages NMT guided by constrained sampling. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2021, 37, 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J. Transfer Learning-Based Neural Machine Translation for Low-Resource Languages. ACM Trans. Asian Low-Resource Lang. Inf. Process. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Robinson, C. N. Robinson, C. Hogan, N. Fulda, and D. R. Mortensen, “Data-adaptive Transfer Learning for Translation: A Case Study in Haitian and Jamaican.” In: Proceedings of the Fifth Workshop on Technologies for Machine Translation of Low-Resource Languages (LoResMT 2022), pp. 35-42, 22. Gyeongju, Republic of Korea. 20 October.

- W. Ko et al., “Adapting High-resource NMT Models to Translate Low-resource Related Languages without Parallel Data.” In: Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, vol. 1, pp. 802-812, 21. 20 August.

- Gunnam, V. Tackling Low-Resource Languages: Efficient Transfer Learning Techniques for Multilingual NLP. Int. J. Res. Publ. Semin. 2022, 13, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.; Bui, N.D. On the scalability of data augmentation techniques for low-resource machine translation between Chinese and Vietnamese. J. Inf. Telecommun. 2023, 7, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Dai, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, S. Improving Many-to-Many Neural Machine Translation via Selective and Aligned Online Data Augmentation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srihith, I.D.; Donald, A.D.; Srinivas, T.A.S.; Thippanna, G.; Anjali, D. Empowering Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning: A Comprehensive Survey on Federated Learning. Int. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Commun. Technol. 2023, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, J.S.; Bhatt, A.K.; Anand, N. Federated Learning; Privacy Preserving Machine Learning for Decentralized Data. Tuijin Jishu/Journal Propuls. Technol. 2023, 44, 167–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Ding, Y.; Tang, S.; Wang, Y. Privacy-preserving federated learning based on partial low-quality data. J. Cloud Comput. 2024, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakre, N.; Pateriya, N.; Anjum, G.; Tiwari, D.; Mishra, A. Federated Learning Trade-Offs: A Systematic Review of Privacy Protection and Performance Optimization. Int. J. Innov. Res. Comput. Commun. Eng. 2023, 11, 11332–11343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Gheini, X. M. Gheini, X. Ren, and J. May, “Cross-Attention is All You Need: Adapting Pretrained Transformers for Machine Translation.” In: Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pp. 1754-1765, 21. Online and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic. 20 November.

- Gupta, U.; Galstyan, A.; Steeg, G.V. Jointly Reparametrized Multi-Layer Adaptation for Efficient and Private Tuning. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, CanadaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 12612–12629.

- Weng, R.; Yu, H.; Luo, W.; Zhang, M. Deep Fusing Pre-trained Models into Neural Machine Translation. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2022, 36, 11468–11476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankford, S.; Afli, H.; Way, A. adaptMLLM: Fine-Tuning Multilingual Language Models on Low-Resource Languages with Integrated LLM Playgrounds. Information 2023, 14, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. A concise analysis of low-rank adaptation. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2024, 42, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Attention is all you need.”. In: Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), vol. 30, pp 5998–6008, 17. 20 June.

- K. Papineni, S. K. Papineni, S. Roukos, T. Ward, and W. Zhu, “BLEU: a Method for Automatic Evaluation of Machine Translation.” In: Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL '02), pp. 311-318, 02. Pennsylvania, USA. 20 July.

- Goyal, N.; Gao, C.; Chaudhary, V.; Chen, P.-J.; Wenzek, G.; Ju, D.; Krishnan, S.; Ranzato, M.; Guzmán, F.; Fan, A. The Flores-101 Evaluation Benchmark for Low-Resource and Multilingual Machine Translation. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguistics 2022, 10, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Lin, “Looking for a Few Good Metrics: ROUGE and its Evaluation.” Proceedings of the 4th NTCIR Workshops, 04. Tokyo. 20 June.

- C. Lin, “ROUGE: A Package for Automatic Evaluation of Summaries.” Association for Computational Linguistics, p. 74-81, 04. Barcelona, Spain. 20 July.

- Chatzikoumi, E. How to evaluate machine translation: A review of automated and human metrics. Nat. Lang. Eng. 2019, 26, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. B. Shukla and B. Chavada, “A Comparative Study and Analysis of Evaluation Matrices in Machine Translation.” 2019 6th International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom), pp. 1236-1239, 19. New Delhi, India. 20 March.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).