1. Introduction

Recent studies underscore the critical role of integrating artificial and human intelligence to enhance translation efficiency, particularly for minority languages. Hybrid methodologies that combine rule-based approaches with neural machine translation have demonstrated significant potential in improving translation quality for under-resourced language pairs [

1]. Proactive learning frameworks have been identified as effective tools for constructing machine translation (MT) systems tailored to minority languages with limited resources [

2]. The No Language Left Behind initiative represents a landmark in scaling human-centered machine translation systems to encompass over 200 languages [

3]. Despite these advances, considerable challenges persist in safeguarding linguistic diversity and meeting the distinctive needs of minority language speakers [

4,

5]. Recent innovations, such as integrating neural translation engines with rule-based systems, have yielded encouraging results in enhancing translation accuracy for endangered languages, including Lemko [

6]. These developments in MT technologies hold substantial promise for supporting language revitalization initiatives and empowering minority language communities [

7].

Marginalized populations experience inequality in power relationships across economic, political, social and cultural dimensions, resulting in discrimination and exclusion (social, political and economic). Marginalized populations are often communally-minded and oftentimes, lead the movements for social justice. Minorities and marginalized populations often experience ethnic assimilation, racism, discrimination, and bullying [

8]. International and national crises often highlight inequalities in the labor market that disproportionately affect individuals from marginalized backgrounds [

9]. Acts of linguistic microaggression against linguistically marginalized populations are another cause of participation failures [

10]. However, multiple ethnic groups can jointly participate in mainstreaming society through cultural diversity and participation fairness. An ethnically mainstream society can only be built through an ethnic group policy based on cultural diversity and fair participation. As a result of promoting ethnic mainstreaming policies, society will show more cultural diversity and fairness and inclusion of social participation, allowing ethnic groups to respect one another.

Millions of people use mobile applications and online translation services to communicate across languages. With the development of artificial intelligence technology, machine translation plays an increasingly crucial role in global communication. Machine translations are becoming increasingly important for minority languages to enter mainstream society. More and more research on machine translation technology focuses on minority languages [

11,

12,

13,

14].

This paper introduces a hybrid AI-driven machine translation system that combines phrase-based and neural machine translation techniques to enhance the quality of Hakka-to-Chinese translation. The proposed system addresses the limitations of purely statistical or neural methods by integrating phrase-based MT with neural approaches, particularly in low-resource settings. The key to improving translation quality is adopting a recursive translation approach, generating parallel corpora dynamically, and leveraging them for continuous profound learning improvements. This methodology enhances immediate translation services for Hakka speakers and contributes to the broader goal of preserving and revitalizing the Hakka language through AI-driven solutions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Low Resources Language

Low-resource languages, often characterized by a limited availability of digital text data, pose significant challenges to the development of effective natural language processing (NLP) and machine translation (MT) systems. Unlike high-resource languages, which benefit from extensive corpora and well-established linguistic resources, low-resource languages face obstacles such as sparse parallel corpora, limited linguistic annotations, and a lack of robust language models. These limitations hinder the ability of traditional MT systems to achieve high-quality translations, particularly when it comes to preserving cultural nuances and idiomatic expressions unique to minority languages. In a pluralistic society, it is more and more difficult to inherit the mother tongue. At this time, a system that can translate the Hakka language is even more needed. However, the Hakka language is a low-resource language. Low-resource languages lack large parallel corpora or manually crafted linguistic resources sufficient to make natural language processing (NLP) applications [

15]. Low-resource languages, like Hakka, often present unique challenges in their integration into modern AI-driven translation systems due to several key characteristics. These languages typically suffer from a scarcity of digitized textual data, resulting in inadequate parallel corpora necessary for training effective machine translation models. Additionally, they possess rich cultural and linguistic diversity, including dialectal variations and unique idiomatic expressions, which are difficult for conventional translation models to capture accurately. Furthermore, many low-resource languages lack standardized orthography or consistent grammar rules, complicating the development of reliable and consistent translation models. Together, these factors make it challenging to create generalized translation systems that can effectively handle the nuances of low-resource languages.

2.2. Machine Translation System

A machine translation system is computer software that takes a text in one language (source language) and translates it into another language (target language) [

16]. Translating text or voice from one natural language to another with or without human assistance is the function of machine translation software. Currently, the best system is a Neural Machine Translation (NMT) that utilizes tens of millions of parallel sentences from the training data. Such a huge amount of training data is only available for a handful of language pairs and only in particular domains, such as in news and official proceedings [

17].

Neural networks are computational models inspired by biological neurons, used extensively in machine learning applications [

18]. They consist of interconnected nodes organized in layers, processing input data to produce outputs [

19]. Neural networks can be implemented in various architectures, including feedforward, convolutional, and recurrent networks, each suited for different tasks [

20]. These structures enable neural networks to perform complex tasks such as image recognition, speech processing, and natural language understanding. NMT represents a significant advancement in machine translation, utilizing deep learning techniques and neural networks to improve translation quality. Unlike traditional statistical methods, NMT aims to build a single neural network that can be jointly optimized for translation performance [

21].

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are a type of neural network designed explicitly for sequential data processing, making them particularly effective for natural language processing tasks like machine translation [

22]. Unlike other neural network types (such as feedforward neural network), RNNs have cyclic connections that maintain internal memory and capture temporal dependencies [

23]. This architecture makes RNNs well-suited for language modeling, speech recognition, and time series prediction. Variants like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU) have shown improved performance in handling long-term dependencies [

24]. Integrating RNN language and translation models into phrase-based decoding systems has demonstrated promising results in machine translation tasks [

25].

Various architectures have been explored, including RNNs, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), and the Transformer model, with the latter showing superior capabilities in handling long-range dependencies [

26]. NMT models typically consist of an encoder-decoder structure, where the encoder extracts a fixed-length representation from the input sentence, and the decoder generates the translation [

27]. Recent developments include attention mechanisms, which allow the model to focus on relevant parts of the source sentence during translation [

21]. While NMT performs well on short sentences, its performance can degrade with longer sentences and unknown words [

27].

Machine translation and language teaching chatbots are all uses of artificial intelligence to enhance language learning. Machine translation can be integrated into dialect learning with the help of neural machine translation. Several advances have been made in NMT. The RNN-based sequence-to-sequence model (Seq2Seq) was proposed in 2014. RNN-based Seq2Seq is a type of Encoder-Decoder model using the RNN. RNN-based Seq2Seq have been widely used as a model for machine interaction and machine translation in end-to-end speech processing, for example, automatic speech recognition (ASR), speech translation (ST), and text-to-speech (TTS) [

28]. Then, the RNN with Attention in 2015 was the evolution of the techniques to solve Seq2Seq problems. The Convolutional Encoder Model for Neural Machine Translation was proposed in 2017.

Finally, the proposed network architecture of the Transformer is based entirely on attention mechanisms and achieves new state of the art results in neural machine translation [

29]. Transformer neural machine translation neglects the RNN and mainly focuses on the self-attention mechanism, with the Transformer being very close to the learning effect at the human level.

2.3. Hakka Corpus

A corpus refers to a text database that scientifically organizes and stores electronic texts, and is an important material for linguistic research [

30]. A corpus linguistically means a large amount of text, usually organized, with a given format and markup. A corpus is a collection of (text, spoken) corpora of a certain scale that is specifically collected for one or more application goals, has a certain structure, is representative, and can be retrieved by a computer program. The corpus is generally used in the fields of lexicography, language teaching and traditional language research. The corpus related to the Hakka language includes the national corpus “Taiwan Hakka Corpus”, which was opened in 2021. The Hakka Affairs Council commissioned the National ChengChi University research team from 2017 to build the first native language corpus. The other Hakka corpus is the Taiwan Hakka Speech Corpus. The biggest feature of the Taiwan Hakka Speech Corpus is it has Hakka speech recognition and speech synthesis corpus of various accents. In the future, it can be combined with artificial intelligence technology to develop Hakka digital applications. Creating parallel corpora is a difficult issue that many researches have tried to deal with [

31]. As a result of the nature of low-resource languages like Hakka language, this issue is more complicated. Currently, the world has around 7,000 languages spoken, but most language pairs don’t have enough resources to train machine translation models. There has been an increase in research addressing the challenge of producing useful translation models in the absence of translated training data [

32]. Machine translation of dialects faces the main problem of lacking parallel data in language pairs. The other problem is the existing data always has a lot of noise or is from a very specialized domain.

3. Hybrid Machine Translation

3.1. Objectives of the Hybrid Machine Translation System

The primary goal of this hybrid machine translation system is to establish a robust and scalable platform for Hakka language translation, addressing the challenges posed by its low-resource nature. The system is designed to facilitate effective communication in Hakka while preserving its linguistic and cultural heritage. To achieve this, the translation model incorporates Hakka culture-specific items (CSI), including idiomatic expressions, proverbs, master words, ancient dialects, and emerging linguistic trends. Additionally, the system supports multilingual translations, enabling seamless conversion between Hakka, Chinese, English, and other Asian languages commonly spoken by Hakka diaspora communities, such as Japanese, Thai, Indonesian, and Malay. A prototype system has been developed to evaluate the proposed hybrid approach. This system primarily focuses on Chinese-to-Hakka literal translation, ensuring fidelity in linguistic representation. The system dynamically adapts to different contextual interpretations, allowing for nuanced translations that accurately reflect Hakka cultural elements.

To enhance cultural representation in translations, the system integrates Phrase-Based Machine Translation, which incorporates an expanded translation lexicon featuring Hakka culture-specific terms. This approach ensures that key cultural expressions are explicitly retained in translations rather than omitted or misrepresented by conventional deep-learning models [

33]. Unlike traditional “black-box” deep learning-based translation models, which often lack transparency in handling culture-specific vocabulary, this system adopts a “white-box” approach, allowing direct control over translation references. By doing so, the system preserves the authenticity of Hakka language expressions while improving overall translation quality.

This hybrid AI model provides a structured methodology for improving machine translation in low-resource languages, balancing linguistic accuracy, cultural relevance, and computational efficiency. Future iterations of the system will continue refining translation accuracy through recursive learning, ensuring that the platform evolves alongside the expansion of Hakka language digital resources.

3.2. Preprocessing

Preprocessing is crucial in optimizing the training dataset for neural machine translation, particularly in handling low-resource languages like Hakka. Raw textual data often contains long sentences, extraneous noise, and inconsistent formatting, negatively impacting model performance. To enhance training efficiency and maintain translation accuracy, this study establishes a preprocessing pipeline to standardize, clean, and refine the dataset before feeding it into the machine translation system. Given that excessively long sentences can increase computational complexity and reduce model effectiveness, a maximum sentence length threshold of 40 Chinese characters is imposed. This constraint prevents overlong sentences from introducing noise into the training process while ensuring the system remains computationally efficient.

This study used UTF-8 encoding for both Hakka and Chinese languages to ensure compatibility across various processing stages. UTF-8 was selected due to its ability to handle diverse character sets, including logographic scripts like Chinese and Hakka while maintaining efficient storage and processing capabilities. This encoding standard ensures the translation pipeline remains robust and avoids character misinterpretation or corruption during text processing. To improve data quality, the preprocessing phase consists of the following five key steps:

1. Sentence Segmentation: Split training sentences based on punctuation marks to enhance structural clarity.

2. Punctuation Removal: Eliminate unnecessary punctuation that may introduce inconsistencies in translation.

3. Synonym Annotation Removal: Remove comments enclosed within “()” or “[]”, which often contain redundant synonym explanations.

4. Ambiguous Symbol Cleanup: Discard “/” or “//” used as separators for alternative expressions, reducing lexical redundancy.

5. Whitespace and Non-Chinese Character Filtering: Strip blank lines, excessive spaces, and non-Chinese characters that do not contribute to model learning.

These preprocessing steps standardize sentence structures, eliminate noise, and enhance dataset consistency, ultimately improving the accuracy and efficiency of the NMT model. Experimental results confirm that segmentation based on punctuation and systematic removal of redundant symbols significantly enhance translation quality. The refined dataset ensures that both phrase-based and neural machine translation models can generate more accurate and culturally appropriate translations for Hakka.

Example of Preprocessing:

Raw Sentence: 這是一個(範例)句子,包含[同義詞],以及/不同/表達方式。

After Preprocessing: 這是一個句子,包含同義詞,以及不同表達方式。

This example demonstrates how redundant annotations, punctuation, and ambiguous symbols are removed to create a cleaner and more standardized dataset for translation model training.

3.3. System Development Process and Architecture

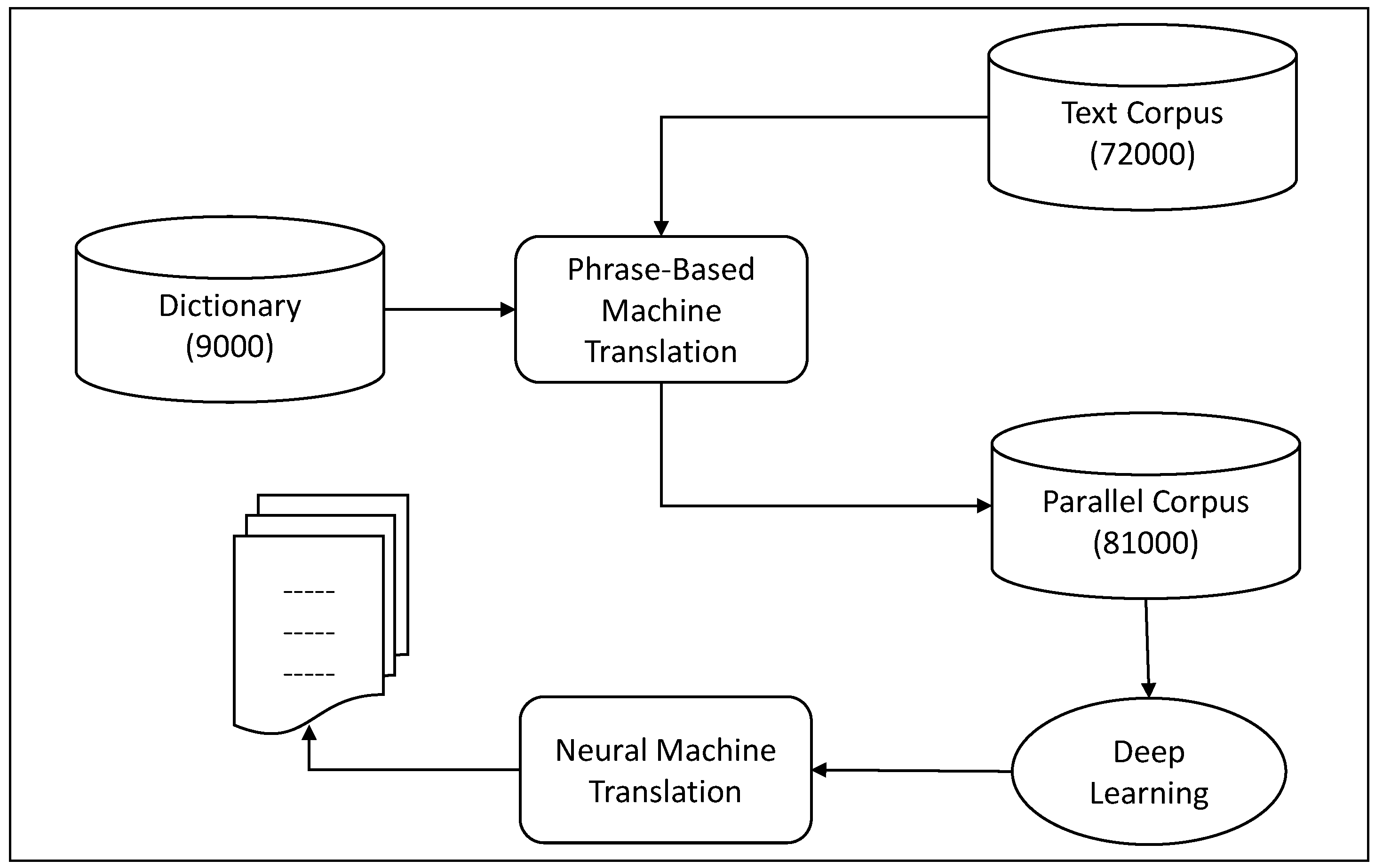

The hybrid machine translation system follows a structured three-stage development process that integrates PBMT and NMT to enhance translation accuracy for low-resource languages like Hakka. In the first stage, PBMT is used to translate a Hakka text corpus, including structured text and dictionary entries, into a parallel corpus, ensuring the preservation of linguistic structures and culture-specific terms. In the second stage, the generated parallel corpus serves as training data for a deep learning-based Transformer NMT model, allowing the system to improve contextual understanding and sentence-level coherence. The third stage involves recursive translation, where new parallel data is iteratively added to retrain the NMT model, continuously refining translation accuracy by expanding the dataset and improving its ability to process Hakka language patterns, idiomatic expressions, and syntactic structures. This hybrid approach effectively combines the rule-based advantages of PBMT with the deep learning capabilities of NMT, while the recursive learning mechanism ensures ongoing enhancement of translation quality.

Figure 1 illustrates the system architecture, highlighting the integration of PBMT, NMT, and recursive learning cycles.

3.4. Neural Machine Translation (NMT)

Neural Machine Translation usually relies on parallel corpora in two languages (source language and target language) to train models. For example, the Chinese-to-English model needs to use millions of parallel corpora as training datasets. However, low-resource languages like minority languages or most dialects do not have enough parallel corpora as training datasets. As open sources of parallel data have been exhausted, one avenue for improving low-resource NMT is to obtain more parallel data by web-crawling. However, even web-crawling may not yield enough text to train high-quality MT models. However, monolingual texts will almost always be more plentiful than parallel texts, and leveraging monolingual data has therefore been one of the most important and successful areas of research in low-resource MT. Recent study has shown how carefully targeted data gathering can lead to clear MT improvements in low-resource language pairs [

34]. To succeed at translating models, data is the most important factor, and curation and creation of datasets are key elements for future success [

32].

3.5. Phrase-Based Machine Translation (PBMT)

A phrase-based machine translation system is a good alternative when designing a dialect machine translation system with limited parallel corpus resources. The Hakka language is one of the eight major dialects of Chinese, and they are all written in Chinese characters. Culture-specific items are added to the phrase lexicon. To fully present the cultural characteristics of Hakka, cultural feature words are manually sorted and added to the phrase lexicon. The translated articles at the stage can better reflect the Hakka cultural characteristics and improve the translation quality. So, the use of phrase-based machine translation with Hakka culture-specific items can achieve good translation quality. The accuracy rate of such translation design has been quite high, but there are still many problems. The original Hakka text is first divided into single words or phrases, and then statistics and a limited vocabulary and phrase comparison table are used to select the most common translation methods for these single-word phrases, which are then recomposed into sentences according to the grammar. Therefore, this study adapted phrase-based machine translation to construct a parallel corpus of Hakka-Chinese. The problem with phrase-based machine translation is it generates the most likely translations based on statistical principles, which are not always the most accurate translations. The use of polysemy words can sometimes be problematic. Second, phrase-based machine translation mainly translates single-word phrases, and the ability to translate sentences has its limits. When sentences are long, complex, ambiguous, or have grammatical exceptions, phrase-based machine translation is prone to mistranslation. When the number of parallel corpus thesaurus is small, compared to the neural machine translation, the translation accuracy rate of using the phrase-based machine translation is acceptable. So, as the parallel corpus resources are limited, phrase-based machine translation can be used. However, translation quality has its limitations and cannot produce high-quality translation results. When a rich parallel corpus is available, neural machine translation can produce high quality translation results.

3.6. Hybrid AI-Driven Translation System Development

Previous research has implemented machine translation systems using Convolutional Neural Networks with Attention mechanisms to translate Mandarin into Sixian-accented Hakka. These studies have addressed dialectal variations by separately training exclusive models for Northern and Southern Sixian accents and analyzing corpus differences. Given the limited availability of Hakka corpora, previous systems faced challenges with unseen words frequently occurring during real-world translation. To mitigate this, past research has employed forced segmentation of Hakka idioms and common Mandarin word substitutions to improve translation intelligibility, leading to promising results even with small datasets. These systems have been proposed for applications in Hakka language education and as front-end processors for Mandarin-Hakka code-switching speech synthesis [

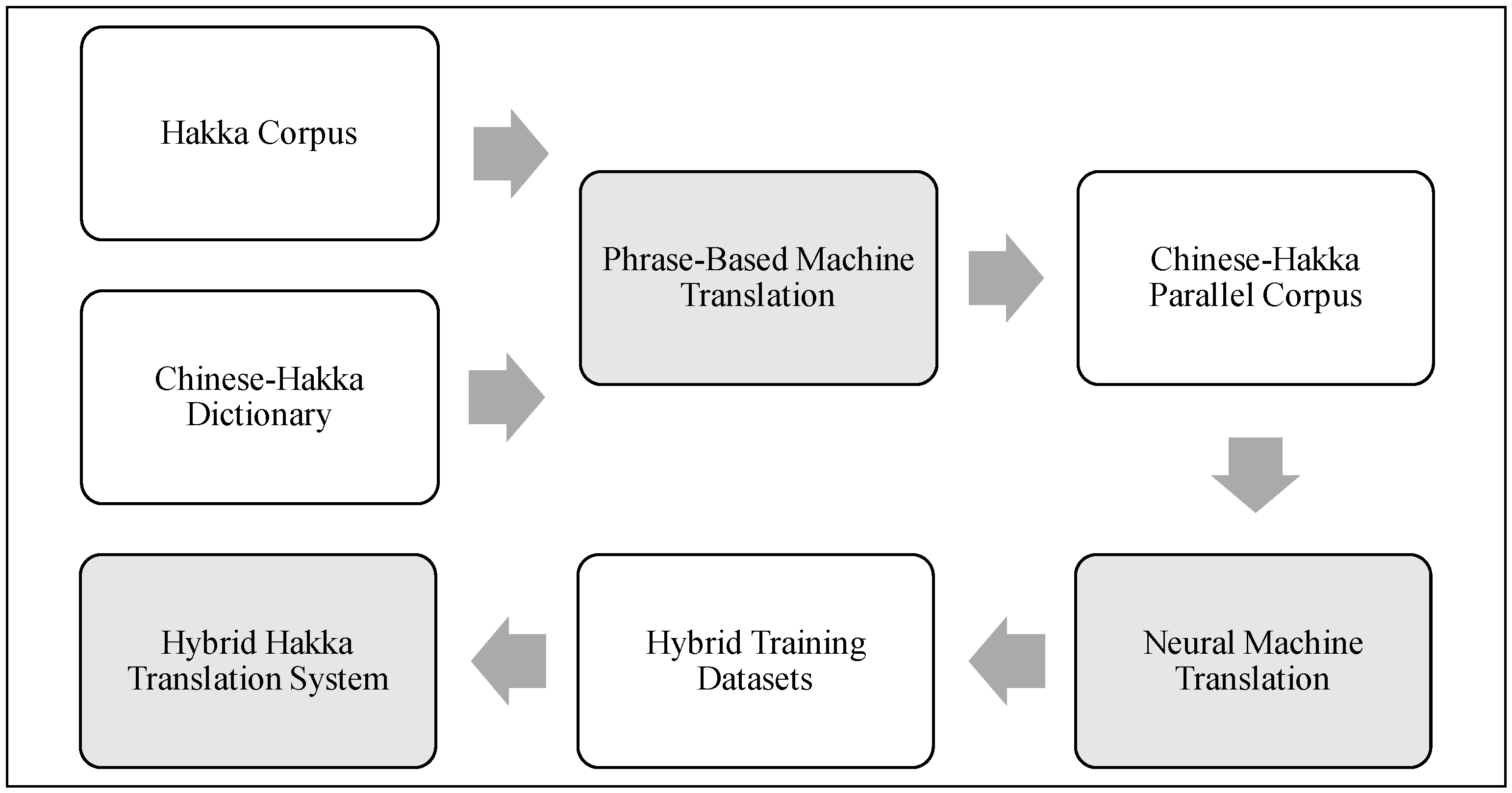

35]. This paper introduces a hybrid AI-driven machine translation system that combines phrase-based and neural machine translation techniques to enhance the quality of Hakka-to-Chinese translation. The system is developed in a multi-stage process. Initially, a phrase-based machine translation (PBMT) approach is implemented using a limited Chinese-Hakka dictionary. This dictionary-driven translation facilitates the conversion of a large volume of Hakka monolingual corpora into Chinese, thereby constructing a Chinese-Hakka parallel corpus, which serves as a training dataset. Subsequently, the parallel corpus is utilized to train a neural machine translation (NMT) model, enabling the integration of phrase-based and deep learning approaches to improve translation accuracy. By leveraging both methods, the proposed hybrid system overcomes the limitations of purely statistical or neural-based models, particularly in low-resource languages. This methodology enhances immediate translation services for Hakka speakers while contributing to the broader goal of preserving and revitalizing the Hakka language through AI-driven solutions. that combine phrase-based and neural machine translation techniques to enhance the quality of Hakka-to-Chinese translation. The system is developed in a multi-stage process. Initially, a phrase-based machine translation (PBMT) approach is implemented using a limited Chinese-Hakka dictionary. This dictionary-driven translation facilitates the conversion of a large volume of Hakka monolingual corpora into Chinese, thereby constructing a Chinese-Hakka parallel corpus, which serves as a training dataset. Subsequently, the parallel corpus is utilized to train a neural machine translation (NMT) model, enabling the integration of phrase-based and deep learning approaches to improve translation accuracy. By leveraging both methods, the proposed hybrid system overcomes the limitations of purely statistical or neural-based models, particularly in low-resource languages. This methodology enhances immediate translation services for Hakka speakers while contributing to the broader goal of preserving and revitalizing the Hakka language through AI-driven solutions. See

Figure 2 for System Workflow.

4. System Evaluation

4.1. Performance of Phrase-Based Machine Translation

The Hakka language in Taiwan has six different accents, including the Sixian (including Nansixian or South Sixian), Hailu, Dapu, Raoping and Zhao’an dialects of Hakka. This study collects a parallel corpus of Hakka language in the form of sentences. Vocabulary from the Certificate of Hakka Proficiency Test (only the part of the Sixian accent, about 5,000 entries), the Ministry of Education dictionary has about 20,000 entries, and further sorting the examples of Hakka attached to the dictionary. There are about 32,000 entries in the parallel corpus in this experiment.

The external Chinese-Hakka language parallel corpus includes the Hakka dictionary, the Hakka entry on the website of the Ministry of Education, and the culture-specific items compiled in this study. These parallel corpora are used in phrase-based machine translation systems. It utilizes statistics and the collected vocabulary of the Chinese and Hakka language to determine the most common translations for these words and phrases. According to the grammar, it is then reorganized into sentences, and the Chinese words are translated into Hakka words and sentences.

To measure the machine translation effectiveness, this study evaluated the closeness of the machine translation to human reference translation using a metric known as BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy). BLEU is an algorithm for evaluating the quality of text which has been machine-translated from one natural language to another. Quality is considered to be the correspondence between a machine’s output and that of a human: “the closer a machine translation is to a professional human translation, the better it is”[

36]. BLEU is the score between 0 and 100, indicating the similarity value between the reference text (human translated text) and hypothesis text (human translated text). The higher the value, the better the translations. A total of 500 entries were extracted from the dictionary of the Ministry of Education as the evaluation corpus of the translation system. These terms are not used as a dataset for translation system training.

To measure machine translation effectiveness, this study evaluated the closeness of the machine translation to human reference translation using the BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy) metric. BLEU is an algorithm for assessing the quality of machine-translated text by comparing it to human reference translations. The score ranges from 0 to 100, where a higher value indicates a higher similarity between the reference and hypothesis texts. The BLEU score is computed using various parameters, including Brevity Penalty (BP), which penalizes translations shorter than the reference translations to prevent artificially high BLEU scores; in our experiments, BP = 1.000, indicating no significant penalty. The ratio represents the proportion of hypothesis (machine-translated) text length to the reference (human-translated) text length, which in our case is 1.062, meaning machine-generated translations were slightly longer. Hypothesis Length (hyp_len) and Reference Length (ref_len) refer to the total number of words in the machine-translated and human-translated texts, which were 9174 and 8641, respectively. The slight difference in length suggests that the machine translation system tends to generate longer output sentences. The BLEU score for the phrase-based machine translation system was 47.52, demonstrating competitive translation quality despite the limited corpus. Brevity Penalty (BP) will be 1.0 when the candidate translation length is the same as any reference translation length. The closest reference sentence length is the best match length [

36].

While BLEU is a widely used evaluation metric, it has limitations, particularly in capturing nuances and contextual meaning in low-resource language translation. Therefore, alternative metrics such as METEOR (Metric for Evaluation of Translation with Explicit ORdering) and TER (Translation Edit Rate) were also considered. METEOR accounts for synonymy, stemming, and paraphrasing, making it a comprehensive evaluation method [

37]. Conversely, TER evaluates the number of edits required to convert machine-generated translations into human translations, providing insight into translation fluency and coherence [

38]. Future studies may integrate human evaluation methods alongside automated metrics to obtain a holistic translation quality assessment.

4.2. Neural Machine Translation with Transformers

Whether English, Chinese or Hakka, a natural language sentence can basically be regarded as a chronological sequence data. The recurrent neural network (RNN) is a class of artificial neural networks where connections between nodes form a directed or undirected graph along a temporal sequence. Given a vector sequence, the RNN returns a vector sequence of the same length as the output.

Treating the sentences in the source language and the target language as an independent sequence, machine translation is actually a sequence generation task. Generate a new sequence (target language) by transforming and meaningfully processing an input sequence (source language). A transformer is a sequence-to-sequence (S2S) architecture originally proposed for neural machine translation (NMT). Models of dominant sequence transduction are based on complex recurrent or convolutional neural networks. Through an attention mechanism, the best performing models also link the encoder and decoder. The Transformer is based entirely on attention mechanisms, with no recurrence or convolutions [

39]. After creating a parallel corpus through the phrase-based machine translation system, it takes this parallel corpus as a training dataset. Deep learning training is conducted to improve translation quality. The remaining entries were used as the deep learning training dataset. After preprocessing, they were imported into a neural machine translation system based on the Transformer Model [

40] for effectiveness evaluation [

41,

42]. The Transformer generates the most sophisticated neural machine translation systems using advanced sequence-to-sequence modeling architecture [

43]. Models of dominant sequence transduction are based on complex recurrent or convolutional neural networks. Through an attention mechanism, the best performing models also link the encoder and decoder. The Transformer is based entirely on attention mechanisms, with no recurrence or convolutions.

4.3. Hybrid Artificial Intelligence Model

Translating dialects and minority languages has always been a major problem in machine translation. There are several approaches to mitigate the problem of low-resource machine translation, including transfer learning as well as semi-supervised and unsupervised learning techniques [

44]. The hybrid artificial intelligence model was adopted combining phrase-based and neural machine translation to translate a Hakka language text into Chinese. The hybrid translation model constructed in this paper consists of three stages: phrase-based machine translation, neural machine translation and recursive translation.

As the Hakka text corpus is collected, the first stage of translation work is then carried out through Phrase-based machine translation to generate a parallel corpus. The generated parallel corpus is utilized as the training dataset to complete the Transformer machine translation training work. Further, the translation quality can be improved by recursive translation with increased parallel corpora.

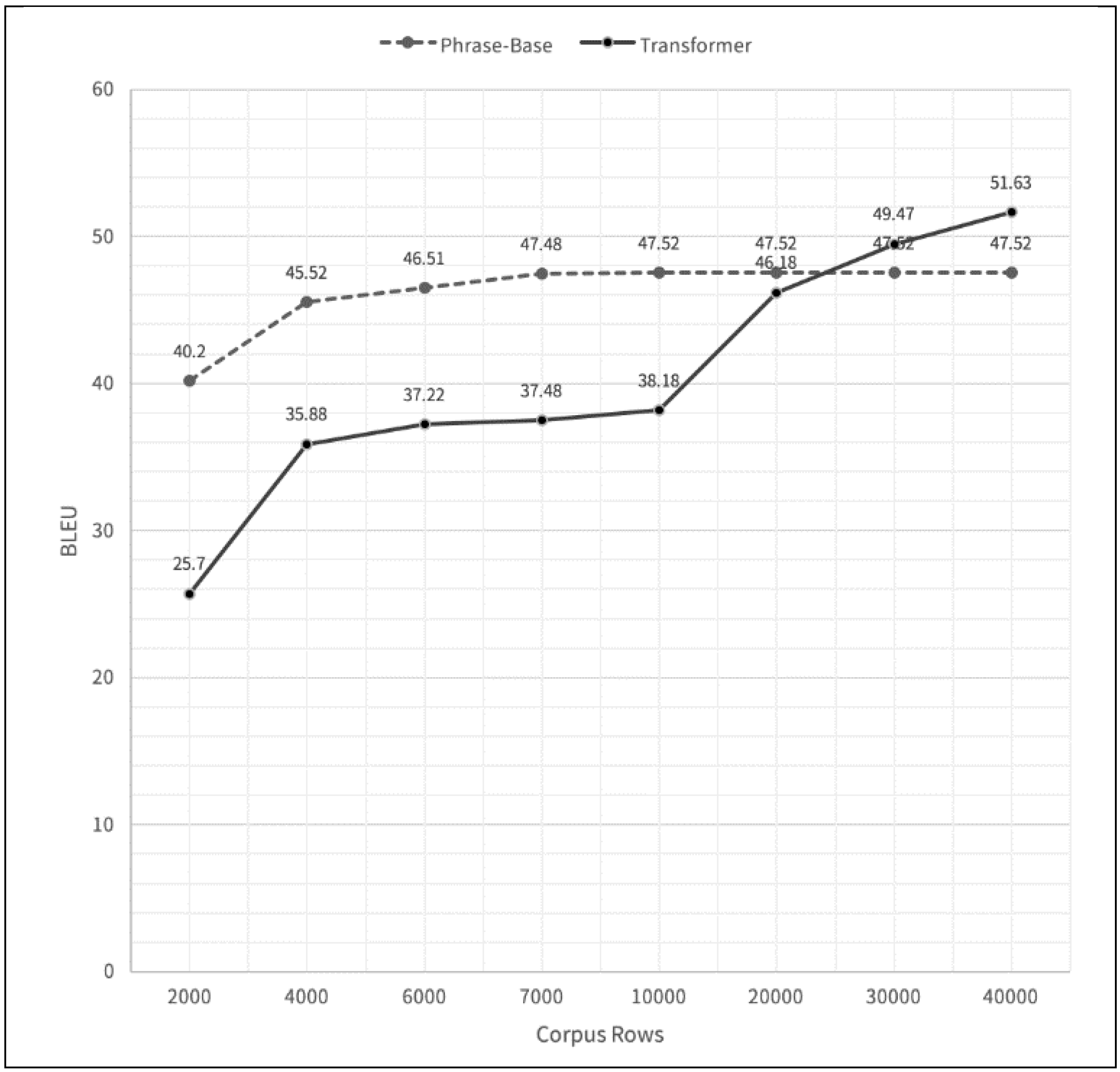

The changes observed in

Figure 3 are primarily due to the impact of increasing training data size and refining the hybrid AI-driven translation system. Initially, PBMT demonstrated better performance when the dataset was small, effectively utilizing statistical alignments. However, as the dataset expanded and the NMT model trained on a more comprehensive parallel corpus, its ability to generalize improved significantly. This resulted in higher BLEU scores in later stages. Additionally, improvements in encoder parameters, including deeper networks, increased hidden units, and additional attention heads contributed to better contextual learning and enhanced translation accuracy. The recursive refinement of the hybrid model, where PBMT-generated translations were incorporated into NMT training, further reinforced learning, making translations progressively more accurate. The observed improvements in

Figure 3 validate the effectiveness of the hybrid approach, demonstrating that while PBMT is advantageous for low-resource settings, the integration with deep learning models yields superior long-term translation performance.

In this study, we implemented an encoder-decoder Transformer model consisting of six layers, with key hyperparameters set as follows: the model dimension (dmodel) was configured to 256, the feed-forward network dimension (dff) was set to 1024, and the number of attention heads (num_heads) was fixed at 2. Additionally, the model employed learned positional embeddings to effectively capture word order dependencies and incorporated weight-sharing between the token embedding and output layers to improve efficiency and reduce the number of trainable parameters. The initial training results yielded a best BLEU score of 46.18.

To address the challenge posed by the limited availability of parallel corpora for Hakka, we utilized a monolingual Hakka text corpus comprising 751,960 words provided by the Hakka Affairs Council. To expand the available training data, we employed a PBMT system to perform reverse translation, converting the monolingual Hakka corpus into Mandarin. This process resulted in constructing a Chinese-Hakka parallel corpus, which served as the training dataset for the final NMT model.

Using this expanded parallel corpus, we conducted additional training cycles to refine the Transformer model. The final model achieved an optimal BLEU score of 51.63, reflecting a substantial improvement in translation quality. The evaluation metrics for this result were as follows: Brevity Penalty (BP) = 1.000, indicating that there was no significant length penalty applied; ratio = 1.015, signifying that the machine-translated output was approximately 1.5% longer than the human reference translations; hypothesis length (hyp_len) = 8774, representing the total number of words in the model-generated translations; and reference length (ref_len) = 8641, corresponding to the length of the human-translated reference corpus. The increase in BLEU score from 46.18 to 51.63 suggests that the quality of Hakka translation was significantly enhanced through the application of reverse translation, data augmentation, and iterative training refinements.

These results demonstrate the effectiveness of integrating PBMT with NMT, allowing for the creation of a robust hybrid translation system. This approach not only improves translation accuracy but also provides a viable solution for addressing data scarcity in low-resource languages like Hakka.

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of artificial intelligence in enhancing the accessibility and sustainability of minority languages through machine translation. By developing a hybrid AI translation model, this research contributes to bridging the linguistic gap for low-resource languages like Hakka, ensuring greater inclusivity in digital communication. The study highlights the strong relationship between language education and minority language preservation, emphasizing the potential of AI-driven translation systems to support language learning, fluency retention, and teaching material development. As translation accuracy improves, these systems can play a pivotal role in assisting Hakka language writing, learning, and digital content creation.

The proposed hybrid AI framework integrates phrase-based and neural machine translation models, employing a recursive learning approach to progressively enhance translation quality as the volume of parallel corpora increases. The findings confirm that a hybrid approach is highly effective for low-resource languages, providing a scalable and adaptable solution where data scarcity is a challenge. By combining structured rule-based translation with deep learning techniques, this model achieves a balance between linguistic accuracy and computational efficiency, making it well-suited for dialect machine translation systems.

Teaching the minority language has a positive impact on the chances of long-term survival and on the level of fluency of the speakers [

45]. Future work will focus on the expansion of translation models and speech synthesis systems across various Hakka dialects, ensuring comprehensive linguistic coverage. Additionally, the project aims to establish an open AI-powered innovation platform that supports Hakka speech synthesis, translation services, and interactive applications. This will facilitate the development of value-added digital tools, AI-driven chatbot services, and cultural preservation initiatives, fostering broader engagement from researchers, developers, and industry stakeholders in advancing Hakka language technology.

Author Contributions

Chen-Chi Chang were responsible for the initial conceptualization of the research and the design of the study’s framework. Yun-Hsiang Hsu was responsible for programming and system development. I-Hsin Fan took charge of data collection and analysis. All authors collaboratively discussed the research findings and contributed to writing the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support from the National United University’s Key Development Project (No. LC113005).

References

- Sánchez-Cartagena, V.M.; Forcada, M.L.; Sánchez-Martínez, F. A multi-source approach for Breton–French hybrid machine translation. In Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Conference of the European Association for Machine Translation; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ambati, V.; Carbonell, J.G. Proactive learning for building machine translation systems for minority languages. In Proceedings of the NAACL HLT 2009 Workshop on Active Learning for Natural Language Processing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Costa-jussà, M.R.; et al. No language left behind: Scaling human-centered machine translation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.04672. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, M. Altered states: Translation and minority languages. TTR: traduction, terminologie, rédaction 1995, 8, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusi, P.; Kolehmainen, L.; Riionheimo, H. Introduction: Multiple roles of translation in the context of minority languages and revitalisation. trans-kom: Zeitschrift für Translationswissenschaft und Fachkommunikation 2017, 10, 138–163. [Google Scholar]

- Orynycz, P. BLEU Skies for Endangered Language Revitalization: Lemko Rusyn and Ukrainian Neural AI Translation Accuracy Soars. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; Springer, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Herbig, N.; et al. Integrating Artificial and Human Intelligence for Efficient Translation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.02978. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, K.L.; Melhus, M.; Høgmo, A.; Lund, E. Ethnic discrimination and bullying in the Sami and non-Sami populations in Norway: the SAMINOR study. Int. J. Circumpolar Heal. 2008, 67, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantamneni, N. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on marginalized populations in the United States: A research agenda. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 119, 103439–103439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sah, P. Linguistic Diversity and Social Justice: An Introduction of Applied Sociolinguistics. Crit. Inq. Lang. Stud. 2018, 15, 228–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcada, M. Open source machine translation: an opportunity for minor languages. In Proceedings of the Workshop “Strategies for developing machine translation for minority languages”, LREC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, S.A. Technological disruption in foreign language teaching: The rise of simultaneous machine translation. Lang. Teach. 2018, 51, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, H. Machine translation and minority languages. In Proceedings of Translating and the Computer 19 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, D.; Moorkens, J.; Carmo, F.D. Fair MT: Towards ethical, sustainable machine translation. Translation Spaces 2020, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakanta, A.; Dehdari, J.; van Genabith, J. Neural machine translation for low-resource languages without parallel corpora. Mach. Transl. 2018, 32, 167–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, V.; Lehal, G.S. Advances in machine translation systems. Language In India 2009, 9, 138–150. [Google Scholar]

- Awadalla, H.H. Bringing low-resource languages and spoken dialects into play with Semi-Supervised Universal Neural Machine Translation. Microsoft Research Blog 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.-H.; Kim, K.W.; Kim, S.; Youn, Y.C. Artificial Neural Network: Understanding the Basic Concepts without Mathematics. Dement. Neurocognitive Disord. 2018, 17, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanchurin, V. Toward a theory of machine learning. Machine Learning: Science and Technology 2021, 2, 035012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lote, S.; B, P.K.; Patrer, D. Neural networks for machine learning applications. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2020, 6, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahdanau, D. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.0473. [Google Scholar]

- Bisong, E. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs). Building Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models on Google Cloud Platform: A Comprehensive Guide for Beginners. 2019; 443–473. [Google Scholar]

- Lipton, Z.C. A Critical Review of Recurrent Neural Networks for Sequence Learning. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1506.00019. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Song, J. Understanding recurrent neural network for texts using English-Korean corpora. Commun. Stat. Appl. Methods 2020, 27, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Sharma, D.M. Experiments on different recurrent neural networks for English-Hindi machine translation. Computer Science and Information Technology (CS & IT) 2017, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J. Neural Machine Translation (NMT): Deep learning approaches through Neural Network Models. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2024, 82, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Van Merrienboer, B.; Bahdanau, D.; Bengio, Y. On the properties of neural machine translation: Encoder-decoder approaches. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karita, S.; et al. A comparative study on transformer vs rnn in speech applications. In 2019 IEEE Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding Workshop (ASRU); IEEE, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Raganato, A.; Tiedemann, J. An analysis of encoder representations in transformer-based machine translation. In Proceedings of the 2018 EMNLP Workshop BlackboxNLP: Analyzing and Interpreting Neural Networks for NLP, The Association for Computational Linguistics; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F. Application of data storage and information search in english translation corpus. Wirel. Networks 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrat, S.; Meftouh, K.; Smaïli, K. Creating parallel Arabic dialect corpus: pitfalls to avoid. In 18th International Conference on Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing (CICLING); Budapest: Hungary, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Haddow, B.; Bawden, R.; Barone, A.V.M.; Helcl, J.; Birch, A. Survey of Low-Resource Machine Translation. Comput. Linguistics 2022, 48, 673–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbačauskienė, J.; Kasperavičienė, R.; Petronienė, S. Issues of Culture Specific Item Translation in Subtitling. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 231, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, T.; et al. Not low-resource anymore: Aligner ensembling, batch filtering, and new datasets for Bengali-English machine translation. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Online: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, Y.-H.; Huang, Y.-C. A Preliminary Study on Mandarin-Hakka neural machine translation using small-sized data. In Proceedings of the 34th Conference on Computational Linguistics and Speech Processing (ROCLING 2022); 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Papineni, K.; et al. Bleu: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In Proceedings of the 40th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lavie, A.; Denkowski, M.J. The Meteor metric for automatic evaluation of machine translation. Mach. Transl. 2009, 23, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snover, M.G.; Madnani, N.; Dorr, B.; Schwartz, R. TER-Plus: paraphrase, semantic, and alignment enhancements to Translation Edit Rate. Mach. Transl. 2009, 23, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; et al. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- TensorFlow. Neural machine translation with a Transformer and Keras, 2024. Available online: https://www.tensorflow.org/text/tutorials/transformer.

- Wang, Q.; et al. Learning deep transformer models for machine translation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.01787, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; et al. Tensor2tensor for neural machine translation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.07416. [Google Scholar]

- FacebookAI. Transformer (NMT) Transformer models for English-French and English-German translation, 2024. Available online: https://pytorch.org/hub/pytorch_fairseq_translation/. (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- Gibadullin, I.; et al. A survey of methods to leverage monolingual data in low-resource neural machine translation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.00373. [Google Scholar]

- Civico, M. The Dynamics of Language Minorities: Evidence from an Agent-Based Model of Language Contact. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2019, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).