4.1. Leaf Plasticity of A. donax Under Irrigation-Nitrogen-Salinity Coupling

This study demonstrated the complex interactions among irrigation, nitrogen application and soil salinity on leaf morphology and function, highlighting the adaptive advantages of

A. donax as a salt-tolerant bioenergy crop. In non-saline soil (S0), moderate irrigation and nitrogen application (N2W2) significantly increased leaf length, width and area (

p < 0.05), consistent with the efficient nitrogen use mechanism proposed by Ceotto et al.[

14]. Under saline conditions (S1 and S2), the effects of irrigation–nitrogen coupling varied. In low-salinity soil (S1), N2W2 maintained a larger leaf area, but the leaf morphology under N1W2 and N2W1 did not differ significantly. This suggested that salinity may weaken the dominant role of nitrogen, whereas water availability and nitrogen fertilization remained as key factors influencing leaf development, consistent with the findings of Cosentino et al. [

26]. In moderate saline soil (S2), N1W2 resulted in superior leaf morphology compared with the other treatments, indicating that an appropriate irrigation–nitrogen ratio (e.g., N1W2) could mitigate salt stress effects on leaf growth. This finding is consistent with the conclusions of Romero-Munar et al. [

17], who reported that

A. donax exhibits leaf plasticity, stomatal regulation and osmotic adjustment to cope with stress. However, excessive nitrogen application (e.g., N3W2) led to deteriorated leaf morphology, reinforcing the concept of ‘non-optimal nitrogen inhibiting growth’ proposed by Zhang et al. [

20]. This finding highlights the need for precise fertilizer management to optimise

A. donax growth in saline environments.

The three-way analysis of variance further clarified the combined effects of environmental variables. Soil salinity had the greatest impact on leaf morphology and photosynthetic parameters, including length, width, area, SPAD,

Pn,

Tr and

Ci (Salinity > Irrigation > Nitrogen), confirming that salinity was the primary limiting factor for leaf expansion in

A. donax (

Table 2. Morphological parameters of fully expanded leaves of A. donax under each treatment in 2024.

| Treatment |

Leaf length (cm) |

Leaf width (cm) |

Leaf length–to –width ratio |

Leaf area(cm2)

|

| S0N0W0 |

15.24±1.41 de |

0.61±0.02 f |

25.02±2.76 ab |

6.13±0.52 f |

| S0N2W2 |

25.73±1.77 a |

1.04±0.07 b |

24.80±3.23 ab |

18.74±0.60 a |

| S1N1W2 |

20.55±2.94 bc |

0.87±0.06 cde |

23.94±4.90 b |

12.39±1.04 cd |

| S1N2W1 |

19.65±1.64 bcd |

0.94±0.04 bc |

20.81±1.09 b |

13.00±1.55 cd |

| S1N2W2 |

22.42±1.99 ab |

1.07±0.01 b |

21.00±1.63 b |

16.75±1.68 ab |

| S2N0W2 |

18.31±1.81 cde |

0.83±0.04 cde |

22.07±3.22 b |

10.56±0.80 de |

| S2N1W1 |

16.73±0.36 cde |

0.83±0.05 cde |

20.13±1.34 bc |

9.48±0.47 def |

| S2N1W2 |

17.14±3.27 cde |

1.28±0.19 a |

13.45±2.22 c |

15.49±4.64 bc |

| S2N2W0 |

14.68±0.71 e |

0.73±0.03 def |

20.11±0.63 bc |

7.29±0.58 ef |

| S2N2W1 |

16.88±1.31 cde |

0.91±0.04 bcd |

18.54±2.12 bc |

10.68±0.60 de |

| S2N2W2 |

23.01±1.87 ab |

0.77±0.07 cde |

30.11±4.33 a |

12.37±0.86 cd |

| S2N2W3 |

17.59±1.73 cde |

0.95±0.08 bc |

18.61±3.17 bc |

11.70±1.10 d |

| S2N3W2 |

17.16±1.39 cde |

0.81±0.08 cde |

21.26±1.95 b |

9.59±1.68 def |

| S3N2W2 |

13.58±0.32 e |

0.70±0.07 ef |

19.53±2.07 bc |

6.34±0.67 f |

Table 3). Although the independent effects of irrigation amount and nitrogen were relatively weak, their interactions with salinity were significant (

p < 0.05), indicating that water management could partially mitigate the negative effects of salt stress. For instance, under S2 conditions, the leaf area in the N2W2 treatment was significantly larger than in N2W0 (

Table 1 and

Table 2). This finding supports Romero-Munar et al.[

17], who found that leaf length and elongation rate in

A. donax were influenced by soil water content. The leaf aspect ratio was not significantly affected by the three-factor interaction (

p > 0.05), suggesting that

A. donax maintains leaf shape stability to adapt to environmental fluctuations, a trait linked to its physiological stress tolerance mechanisms, such as stomatal regulation[

4]. Similarly, Pompeiano et al.[

27] reported that

A. donax exhibits an integrated response mechanism and environmental plasticity under controlled drought conditions. Overall,

A. donax sustains leaf functionality in saline soils by dynamically adjusting water and nitrogen use efficiency. However, its production potential requires further optimisation through phased and precise resource management strategies.

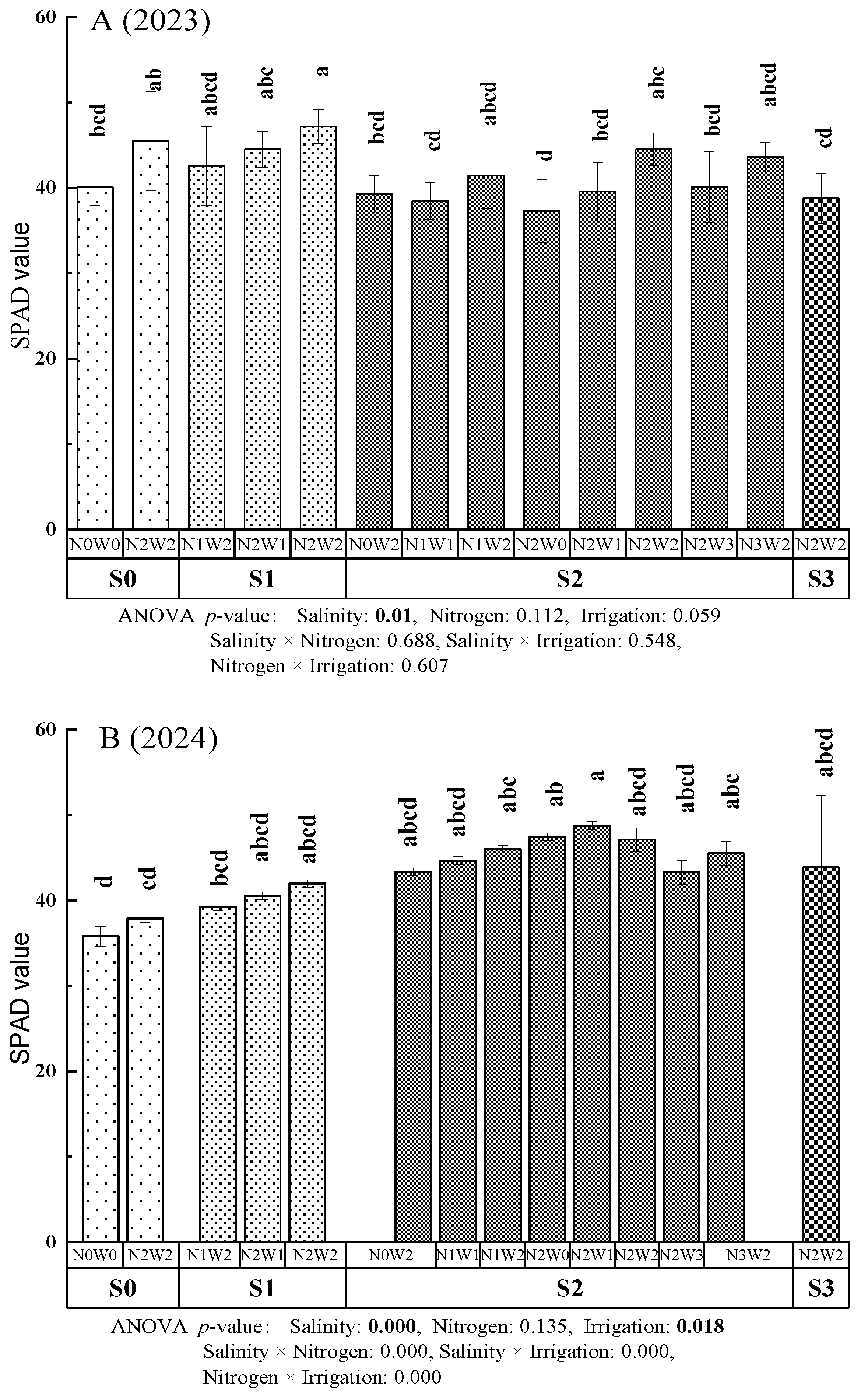

The findings on nitrogen, water and salinity coupling conditions highlighted the complex relationship between leaf structural adaptation and photosynthetic function in

A. donax. The highest SPAD values, reflecting chlorophyll content and photosynthetic potential, were observed under S1N2W2 treatment, suggesting that mild salinity combined with optimal water and nitrogen inputs enhances chlorophyll synthesis and leaf structural integrity. This aligns with Sánchez et al.[

4], who reported that

A. donax employs morphological and physiological adaptations, such as stomatal regulation and nitrogen translocation to optimise photosynthetic efficiency under stress. However, the absence of significant differences in SPAD values among most treatments (

p > 0.05) suggests that

A. donax maintains relatively stable chlorophyll content across varying environmental conditions, likely due to its extensive root system and efficient resource allocation mechanisms [

14]. The dominant influence of soil salinity on SPAD values (Salinity > Irrigation > Nitrogen) further highlights the critical role of salinity in shaping leaf structural properties, which in turn determine photosynthetic capacity.

The photosynthetic parameters (

Pn,

Tr,

Gs and

Ci) further illustrate the functional consequences of structural adaptation. The S1N2W2 treatment, which produced the highest

Pn,

Tr and

Gs values, shows that mild salinity combined with sufficient water and nitrogen can enhance Gs and Tr, thus maximising carbon assimilation. This finding supports by Romero-Munar et al.[

17], who found that

A. donax optimises stomatal behaviour to balance water loss and CO₂ uptake under stress. The significant decline in

Pn and

Tr under severe salinity (S3N2W2) compared to moderate salinity (S2N2W2) highlights the threshold beyond which structural damage impairs photosynthetic function. The absence of significant interactions among nitrogen, irrigation and salinity (

p > 0.05) suggests that

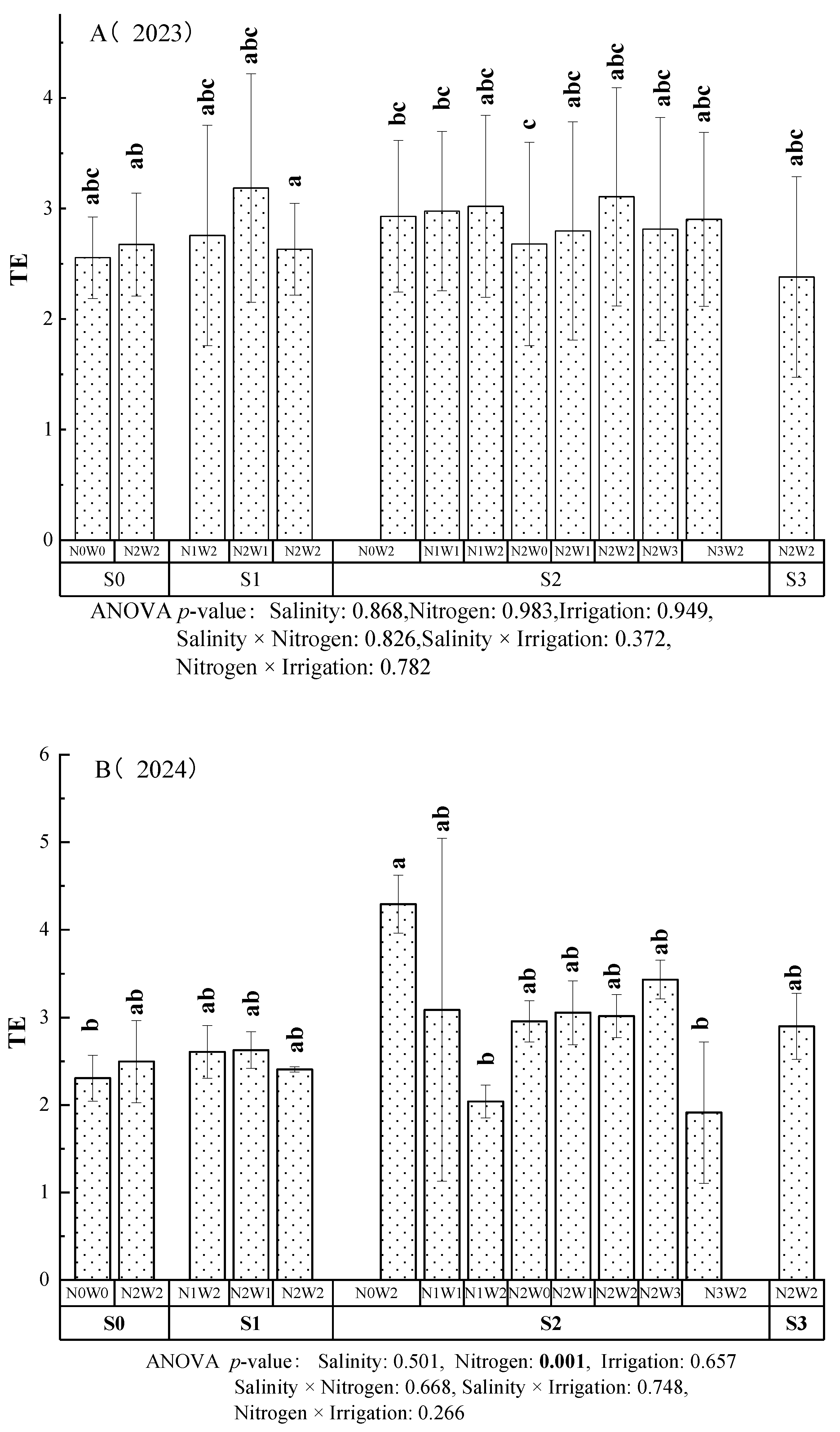

A. donax relies on integrated structural adaptations rather than isolated responses to individual stressors. Furthermore, the TE results, with the highest values observed under S1N2W1 treatment reinforce the idea that optimal water and nitrogen management can improve water-use efficiency without compromising photosynthetic performance—a key adaptation for survival in resource-limited environments [

18]. These findings highlight how the structural resilience of

A. donax leaves underpins its functional plasticity, enabling it to maintain photosynthetic efficiency under diverse environmental conditions.

4.2. Water Physiology of A. donax Under Irrigation-Nitrogen-Salinity Coupling

Our results on water physiology of expanded leaves in A. donax demonstrated that LER, LFW and LDW were dynamically influenced by interactions between salinity, nitrogen and irrigation. Under non-saline conditions (S0), N2W2 significantly increased LER and LFW, indicating that optimal nitrogen and irrigation supply synergistically promoted leaf expansion and biomass accumulation. However, under salinity stress, these responses became more complex. For example, at moderate salinity (S2), N1W2 significantly increased LER, LFW and LDW compared to N0W2, suggesting that moderate nitrogen and adequate water consumpation (W2) could alleviate salinity-induced growth limitations. In contrast, higher salinity (S3) combined with N2W2 reduced LER but increased SLW, suggesting a shift towards leaf thickening under stress. The N2W3 treatment under S2 further increased LER, LFW and LDW, highlighting the importance of increased water input (W3) in sustaining growth under salinity. Notably, the significant Nitrogen×Irrigation interaction highlighted that water availability modulates nitrogen efficacy: while N2W1 under S1 improved LER and LDW, N2W2 reduced LFW and LDW, likely due to altered resource partitioning under different water consumption. These results highlighted the role of nitrogen and water management in balancing leaf expansion, biomass allocation and stress adaptation in saline environments.

In this study, the RWC values varied from 94.84 % to 98.33 % under all irrigation-nitrogen-salinity coupling treatments. These findings indicated no significant plasticity in the RWC of

A. donax leaves, which would provide insights into its adaptive mechanisms under stress. Stable and high RWC performance was consistent with Claudia et al., they detected that

A. donax presented the highest RWC with the value of 85-90 % under watered or non-watered conditions [

15]. Müller et al.[

23] similarly reported no significant differences in RWC between 0 mM and 80 mM NaHCO

3 and Na

2CO

3 salinity stress, with

A. donax exhibiting higher RWC and transpiration intensity. The stability of these parameters suggested that salinity did not affect stomatal movement. However,

A. donax responded to elevated salinity with increased WSD, particularly under extreme salt stress (S3). This was consistent with Pompeiano et al.[

16], who found that

A. donax experienced physiological adjustments such as osmotic regulation and cellular water retention to mitigate salinity stress, and water availability could enhance biomass strongly. The significant reduction in RWC under severe salinity (S3N2W2) compared with moderate salinity (S2N2W2) suggested that while

A. donax could maintain water balance under mild to moderate stress, extreme salinity disruptd its water retention capacity, leading to higher WSD. Additionally, the significant effects of nitrogen and irrigation interactions on LFW, LDW, and SLW highlighted the importance of balanced resource management in maintaining leaf structural integrity and water status. These results suggested that although

A. donax exhibited a high degree of plasticity in leaf water content, enabling adaptation to diverse environmental conditions, its resilience was limited under extreme salinity.

4.3. Biomass Accumulation and Allocation of A. donax Under Irrigation-Nitrogen-Salinity Coupling

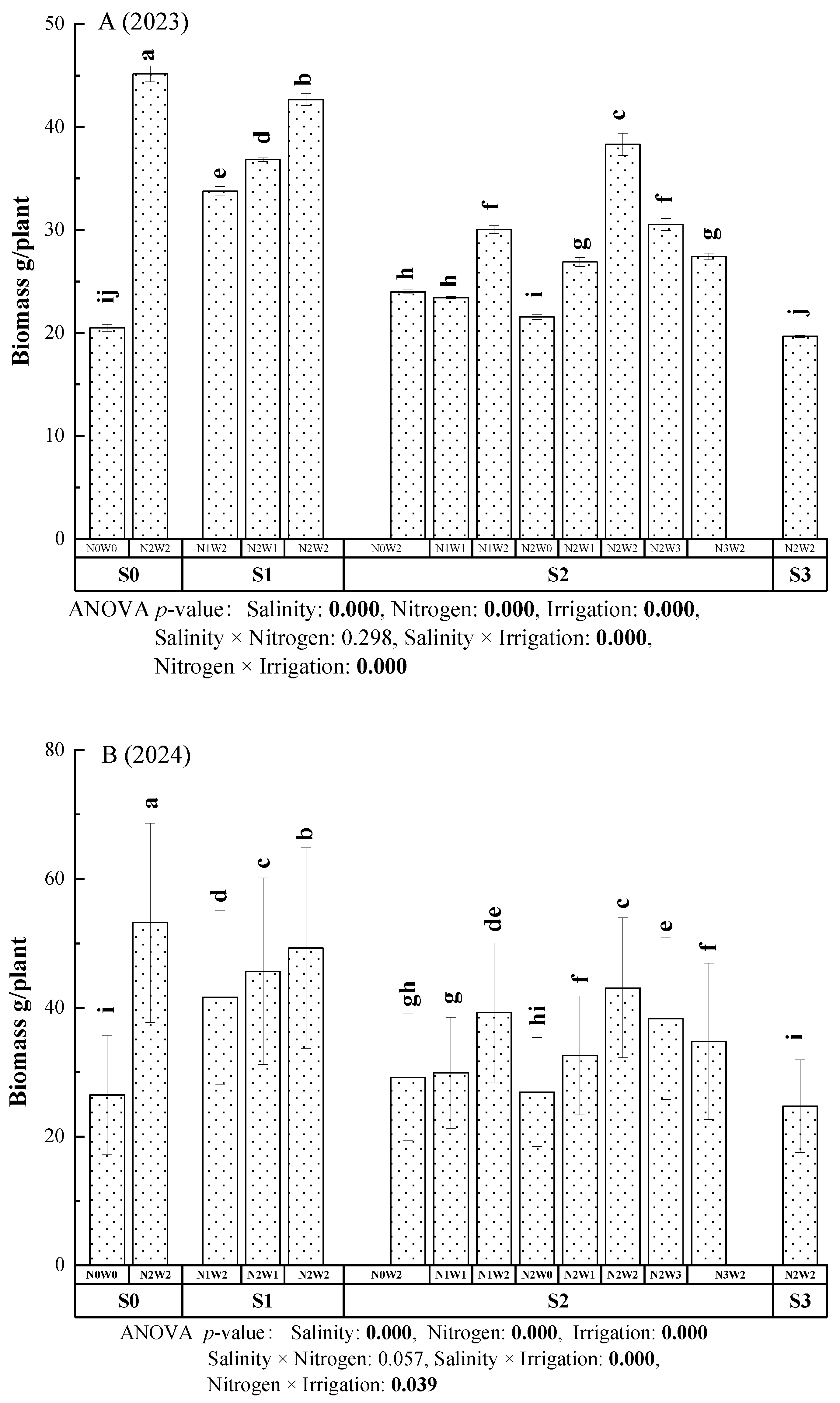

Our results demonstrated that

A. donax employed dynamic biomass accumulation and allocation strategies under irrigation-nitrogen-salinity coupling conditions, reflecting its adaptability to environmental stress. The highest biomass accumulation observed in the S0N2W2 treatment in 2023 (45.16 g/plant) highlighted the synergistic benefits of optimal water and nitrogen inputs in non-saline soils, where resource availability aligned with the growth potential of plant [

28]. However, even under mild or moderate salinity (S1 and S2), N2W2 treatment consistently maximised plant height, leaf number and total biomass, indicating that

A. donax prioritised resource acquisition and photosynthetic efficiency under stress. This supported the findings of Sánchez et al.[

4], who reported that

A. donax optimised nitrogen translocation and stomatal regulation to sustain growth under suboptimal conditions. The significant biomass reduction under severe salinity (S3N2W2, 19.68 g/plant) highlighted a critical threshold beyond which salt toxicity irreversibly impaired physiological processes, aligning with Ullah et al.[

29], who emphasised the coordination between structural and physiological traits in leaves as key to their response to environmental variation. This coordination enabled plant to adjust leaf structure and physiological functions to optimise photosynthetic efficiency and biomass allocation patterns [

6,

30]. The dominant influence of soil salinity on biomass accumulation underscored salinity as the primary limiting factor. At the same time, interactions such as Salinity × Irrigation and Nitrogen × Irrigation suggested that water and nitrogen management could partially mitigate salt-induced growth suppression. In moderate saline soils (S2), increasing nitrogen (from N0 to N2) or irrigation (from W0 to W2) significantly enhanced aboveground biomass allocation, demonstrating the morphological plasticity of

A. donax in response to habitat heterogeneity [

31]. Adequate water and nitrogen inputs were essential for high biomass yields in mild and moderate saline soils [

12].

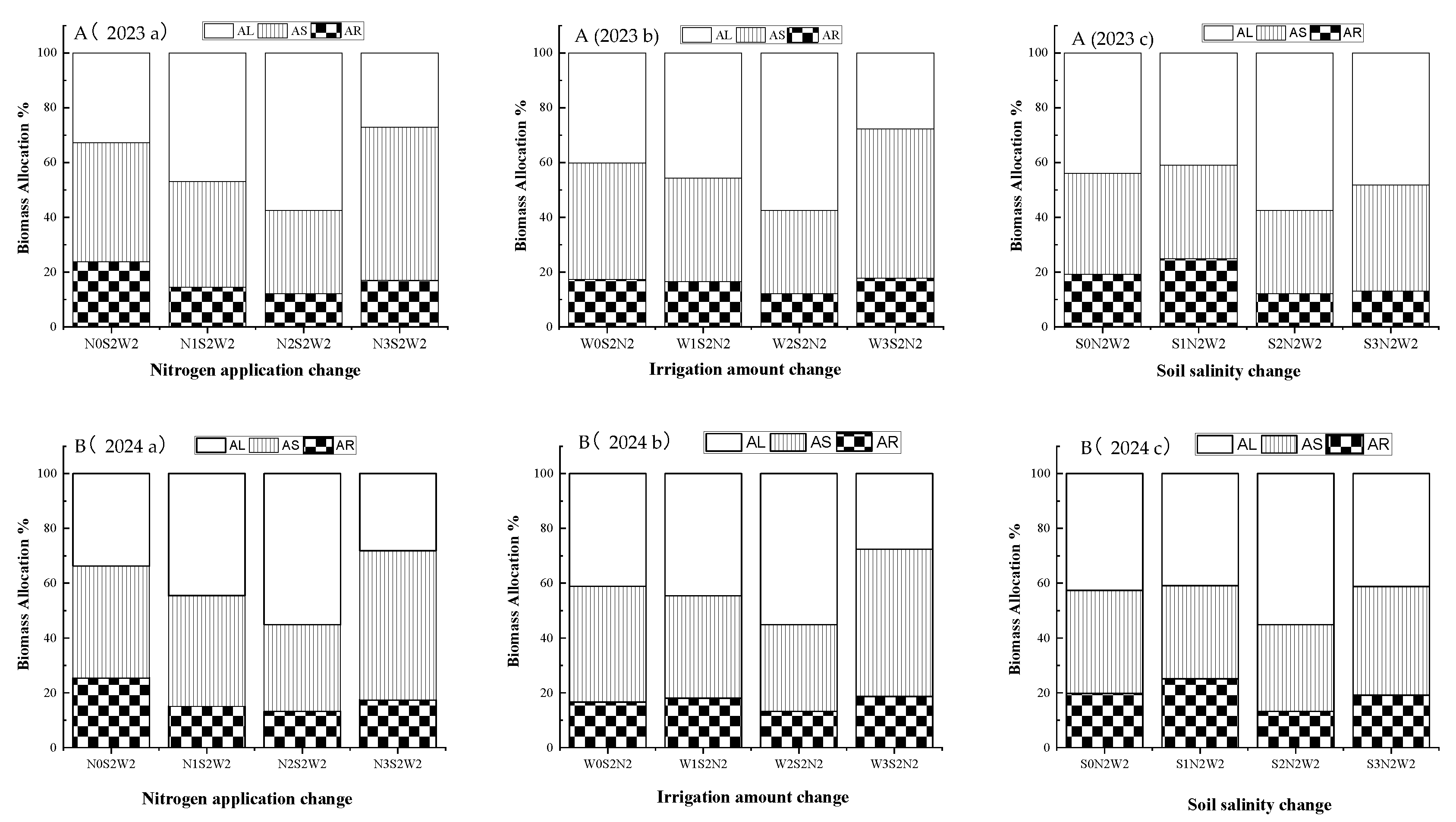

Plants compete for nutrients, water and light, which are often scarce or unevenly distributed. Biomass allocation provides insights into how species respond to environmental limitations [

32]. The biomass allocation patterns of

A. donax under irrigation-nitrogen-salinity treatments further illustrated its adaptive plasticity performance. Under low salinity (S1), the highest root biomass allocation (24.86%) in N2W2 treatment reflected a ‘root-foraging’ strategy to enhance water and nutrient uptake. In moderate salinity (S2), the shift towards aboveground dominance (75.14% of total biomass) indicated greater investment in leaves and stems to maximise light capture and carbon assimilation (

Figure 4). In high saline soils (S3), preferential allocation to leaves ( > 40%) over stems and roots suggested a strategy to maintain photosynthetic capacity and offset salt-induced metabolic costs despite reduced total biomass. The decline in root allocation with increasing nitrogen or irrigation in moderate saline soils (S2) suggested that greater resource availability reduced the need for extensive root systems, allowing more investment in aboveground growth. These findings aligned with that of Zhang et al.[

20], who reported that non-optimal nitrogen disrupted biomass partitioning, highlighting the importance of balanced fertilization. The significant interaction effects of Salinity × Nitrogen and Nitrogen × Irrigation on stem and leaf biomass further emphasised the need for tailored water–nitrogen management to optimise resource use efficiency. Collectively,

A. donax employed a dual strategy: under low stress, it maximises total biomass through synergistic resource inputs, whereas under salinity, it reallocates biomass to sustain functional organs, ensuring resilience at the cost of reduced productivity—a trade-off essential for its ecological success in marginal environments [

18]. In this study, the aboveground biomass allocation percentage (including stem and leaf biomass) of

A. donax ranged from 75.14% to 87.91%, exceeding the 20%–60% reported by Di Nasso et al.[

33]. The variation in dry matter percentage suggests differences in composition and specific fibre types, which can be used in different conversion technologies (e.g., thermochemical processes) for downstream applications. It is necessary to investigate the fibre pattern of

A. donax under irrigation-nitrogen-salinity coupling conditions, as Ceotto et al.[

14] reported that biomass composition is linked to growth duration and harvest time, with the fraction of leaves in total biomass decreasing progressively.

In the 3.6 section, we conducted regression analysis and revealed significant but complex interactions among soil salinity, nitrogen application, and irrigation amount in influencing biomass accumulation in

A. donax. Soil salinity (X₁) exhibited a substantial negative direct effect (P₁y = −0.707), underscoring its detrimental impact on growth. Conversely, irrigation (X₃) and nitrogen (X₂) demonstrated positive direct effects (P₃y = 0.511, P₂y = 0.391), with irrigation exerting a stronger influence under different salinity conditions (

Table 12). The high coefficient of determination (

R² = 0.691) confirmed a robust linear relationship among these factors, though 30.9% of variation in biomass remained unexplained, suggesting additional unaccounted variables. Acturally,

A. donax depends on its rhizome, acts alternatively as a source and sink of nutrient, furtherly optimizes nutrient recycing between under-ground and above-ground [

16]. Our results clearly demostrate that irrigation and nitrogen have a significant impact on the leaf photosynthesis and yield during the experiment period. However, as a modified ARMIDA model of

A. donax reported, the base temperature, leaf area index and radiation intercepted during the growth period were also the main factors conductive to final yields [

11]. Moreover, the negative indirect effects of nitrogen and irrigation, coupled with salinity-mediated pathways, highlight potential trade-offs or antagonistic interactions in saline conditions. These findings emphasize the need for integrated management strategies in saline soils, considering the nuanced interplay among these factors. Further research should explore additional contributors, such as soil properties or microbial activity, to enhance biomass productivity.