Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) has progressed over the years. The structure and functionality of knee joint cartilage are deteriorated by trauma, inflammation, and other risk factors. Owing to irregularities or loss of cartilage, almost six million people visit hospitals. With an estimated 14% lifetime risk [

1], knee OA is expected to cost US 185 billion in medical expenses per year [

2]. As there is no FDA-approved medication, its prevalence is increasing [

3].

Posttraumatic OA (PTOA) affects a significant portion of the US population with various etiological factors, yet there are few reliable animal models. Therefore, identifying a specific, easily reproducible mouse model could help test various therapeutic agents and biomarkers for OA prevention and treatment[

4,

5,

6]. Commonly used PTOA models include chemically induced spontaneous, non-invasively induced, and surgically induced models. Our earlier studies utilized chemical-induced progressive aging, genetics, human cartilage implants, and other models of OA [

7,

8,

9].

Current surgical models, which are largely utilized in OA studies, vary in procedure, lack reliability, and are not reproducible for diagnostic and therapeutic preclinical applications. The commonly used PTOA surgical models, such as anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) transection and destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM), are less reproducible [

10]. The ACL transection model requires higher surgical expertise, as it is highly invasive, whereas the DMM is less invasive than the ACL.

The DMM model has evolved to become the gold standard; however, a major limitation is that not all mice exhibit reproducible changes. Variations in the subluxation/dislocation of the patella in some DMM mice were noted because of forced destabilization during surgery. Additionally, early-stage gait disparity and functional changes were not observed in DMM compared to sham mice to study joint function [

11]. The DMM procedure involves transecting the knee capsule entirely, which can lead to nonphysiological inflammatory changes[

12]. Non-invasive trauma-induced models do not recapitulate pathological and inflammatory molecular variations. The DMM model shows more severe PTOA-like changes in male mice than in female mice[

13,

14]. Notably, OA is more common in females than in males. However, DMM surgery does not recapitulate the sex-linked severity of OA observed in female patients. Refinement of the surgical procedure resulted in some changes in pain, but not in the OA phenotype [

15]. Thus, given the limitations of the commonly used DMM model, a specific model must be developed.

In this study, we established a modified medial meniscectomy (MMM) model of PTOA that is less invasive, highly reproducible, and can assess structural and functional changes. The established meniscectomy model can be used for various diagnostic and therapeutic applications. Next, we performed a functional assessment of the knee joint using the von Frey test for allodynia pain assessment and treadmill exhaustion test for endurance. We also evaluated the variation in gene expression patterns and biological processes in MMM models compared with those in mice with sham controls. This functional assessment and molecular variation in the MMM could enhance the evaluation of preclinical OA-related studies.

Methods

Animal Experiments

All mouse (C16BL/6J) experiments were performed with the guidance, regulation, and approval of the Boston University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC; approval number AN-15387). Animal studies adhered to the ARRIVE standards.

To perform MMM surgery on the knee, the mice were fully anesthetized using isoflurane until they became fully unconscious and continued at the same flow rate throughout the procedure. In the induction chamber, 2.5% isoflurane in 100% oxygen was administered at a flow rate of 1 L/min. Anesthesia was maintained using a 2.5% mixture at 0.5 L/min throughout the surgery. Further procedural details are described in the Results section.

Treadmill Exhaustion Test

Preclinical behavioral evaluation of chronic pain and inflammation can benefit from treadmill behavior[

16]. The treadmill exhaustion test was performed using a standard protocol[

17] before and after the MMM surgery. Prior to performance evaluation, mice (n=8 mice/group) were provided a day of rest after three days of acclimatization to treadmill running (TSE Systems)[

17]. The acclimatization process included five minutes of rest on the treadmill conveyor belt, five minutes of running at 7.2 m/s, and five minutes of running at 9.6 m/s. On day 0, mice were subjected to a graded maximum running test that began with a 5-minute rest period, followed by a running protocol that started at 4.8 m/min and elevated by 2.4 m/min every 2 min. At all times, the belt was retained at an 5-degree inclination. The maximum running speed was measured as the fastest rate at which mice could run for 5 s without hitting the treadmill's electric shock grid.

Allodynia Test

Allodynia was assessed using the Von Frey Hairs test, which involves pricking the hind paw 3-5 times with filaments of varying diameters. Specifically, Mice (n=10 mice/group) were allowed at least 15 min to get used to the test equipment after being placed in an acrylic chamber above a metal grid floor. Initially, we waited for the mouse to stop its exploratory behavior, and a von Frey filament was pushed on the plantar surface of the paw until it buckled and then maintained there for a maximum of three seconds. A response was noted if the paw was sharply withdrawn when the filament was applied, or flinched when the filament was removed. The experimental groups were not disclosed to the researchers who conducted the tests.

Histology

Mouse knee joints (n=6 mice/group) were paraffin-embedded, decalcified, examined histologically, and immunostained. Safranin-O/Fast Green (American Mastertek Inc.) staining was performed as described previously [

8]. Histology and OARSI scoring were performed as previously earlier[

7,

8,

9]. A digital slide scanner was used to scan the stained tissues (Panoramic MIDI, 3D Histech).

Sample Collection and RNA Extraction

Four months after the MMM surgery, the mice were sacrificed following standard euthanasia guidelines. Knee joints were obtained by cutting the complete leg from the proximal epiphysis of the femur, clearing it of hairs, muscles, and fat tissue with scissors and scalpels, and rubbing it with gauze. Complete knee integrity was preserved, and the joints were collected by cutting the distal femoral metaphysis and proximal tibia. Samples (n=4 mice/group) were snap frozen and crushed, total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (QIAGEN) and total 400ng of total RNA per sample was sent for sequencing to Novogene (Sacramento, California, USA).

Results

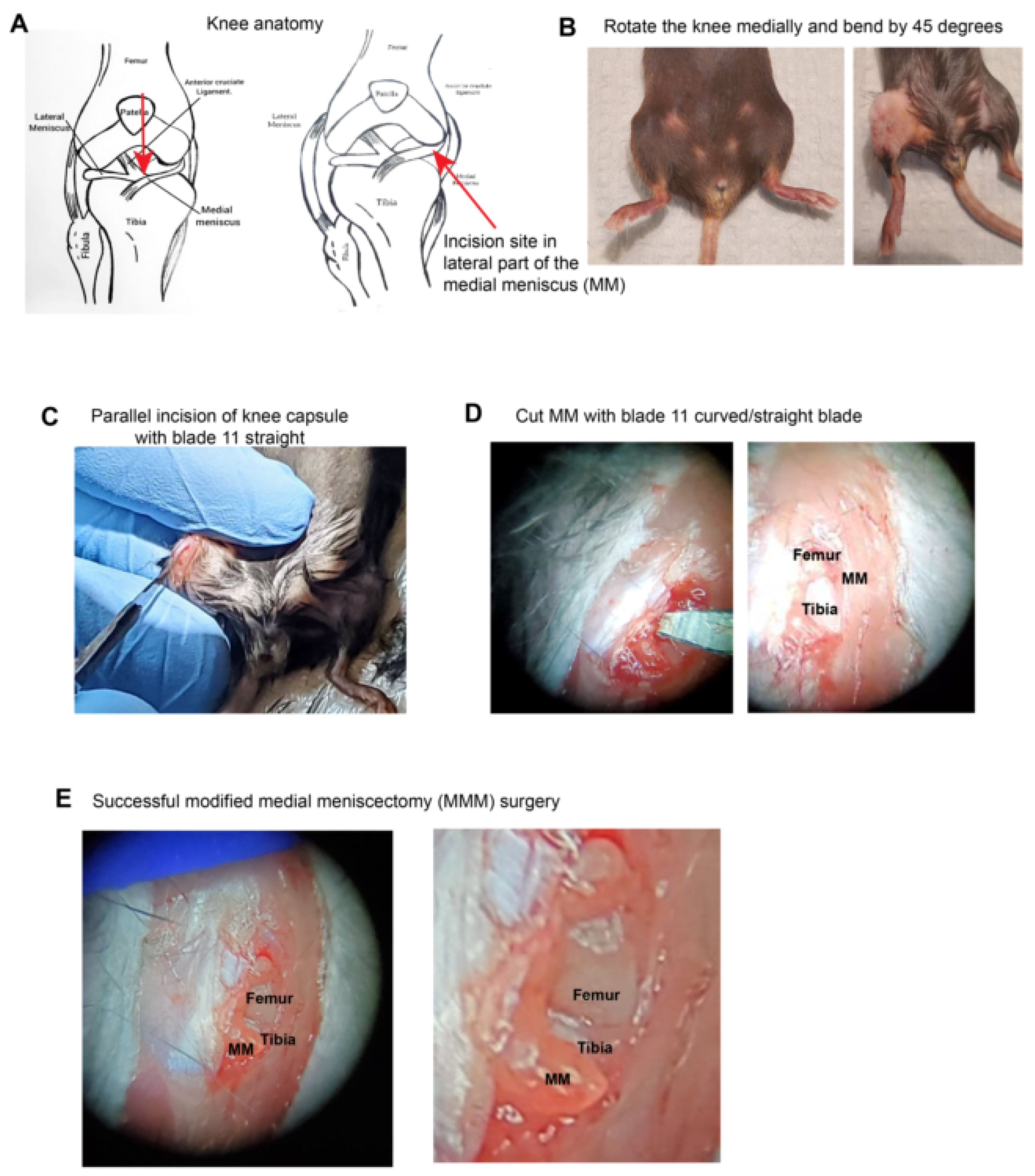

The MMM Model Is Reproducible and Less Invasive

To study the post-traumatic OA model, the traditional DMM model involves cutting the medial meniscus after dissecting the medial capsule and retracting the ligament. Thus, this model required a significant incision at the mid-point (

Figure 1 A). However, the new lateral meniscectomy (MMM) model protocol involves bending the knee medially to access the medial meniscus laterally, which can be dissected using a dissection microscope (

Figure 1 B). This approach is less invasive and does not require complete dissection of the knee capsule.

At 45 °, the knee joint was bent and turned medially, followed by an incision on the lateral side of the knee joint capsule and lateral cutting of the medial meniscus with an 11 curved/straight blade (

Figure 1 C-E). When MMM surgery is successful, the femur and tibia at the knee joint are clearly visible (

Figure 1 F-G), and the medial meniscus, which is transected and visibly popped out under higher magnification (

Figure 1 H). Finally, the joint capsule was sutured with Vicryl suture 4.0, followed by skin suturing. Thus, we established a novel meniscectomy model that offers the advantages of a minimal incision size, reproducibility, and ease of validation. To assess structural and functional changes, we performed histological staining, treadmill exhaustion test, allodynia assessments, and quantitation by ICH.

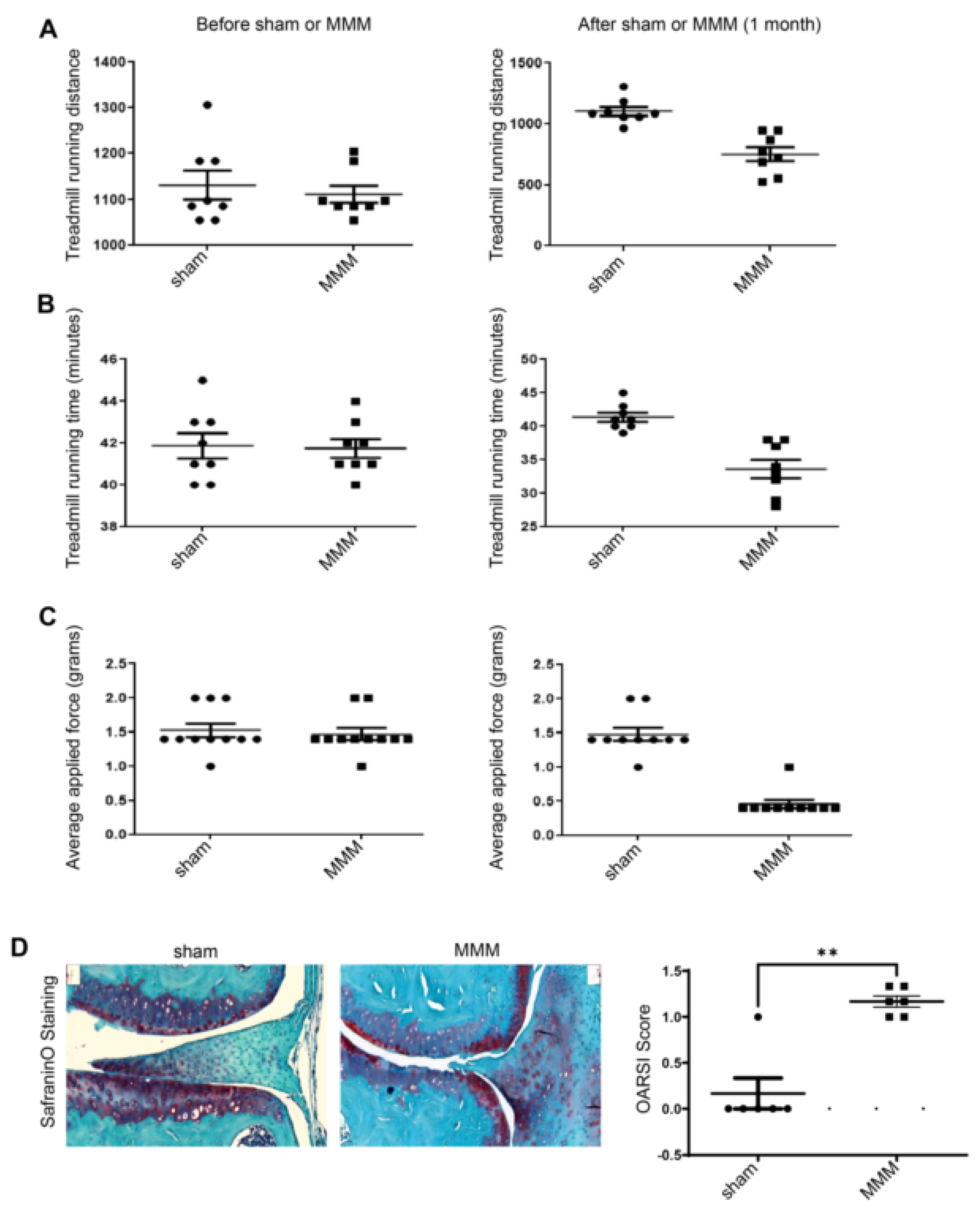

MMM Model Could Be Used to Study Pain, Function, and Degeneration

To evaluate whether the new model induced functional effects, sham and MMM surgeries were performed on 6-month-old C57BL/6 mice (n=6-10; equal male/female). These mice were assessed using the treadmill exhaustion test and Von Frey hair test 2 days before and 31 days after MMM surgery. The treadmill exhaustion test (

Figure 2 A-B) showed that treadmill running time and distance remained the same before MMM in all groups, whereas they were impaired on day 31 in the MMM group. Control mice ran faster and further than the MMM mice (

Figure 2 A, B). The data (

Figure 2 C) indicate that the hind paw withdrawal reflex was similar across all groups at a 1.5 g force with Von Frey hairs before MMM, whereas sensitivity increased to 0.4 g fibers in the MMM group. Finally, Safranin-O staining for proteoglycan showed significant differences at four months post-MMM. The quantification of proteoglycan staining revealed reduced staining in the meniscectomy group. The total OARSI score increased in the DMM group (

Figure 2D). MMM surgery induces OA-like functional and structural changes.

Discussion and Conclusion

The modified medial meniscectomy (MMM) mouse model represents a significant advancement in post-traumatic osteoarthritis research by addressing the limitations associated with existing models, such as DMM and ACL transection. The DMM has been used extensively in various studies [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. OA shows changes in the synovium, meniscus, and other joint tissues and induces pain and disability in preclinical animal models [

23,

24,

25]. Studies have shown that mouse PTOA can also affect Aβ accumulation in the brain[

26]. Murine PTOA induces inflammation and pain[

27,

28,

29,

30]. Murine PTOA models have been used in mechanistic[

31] and therapeutic studies [

32,

33,

34].

The key benefits of the MMM include its reduced invasiveness and suitability for investigating both pain-related behaviors and structural changes. Unlike the DMM and ACL models, which are prone to procedural inconsistencies and operator-dependent variations, the MMM model consistently replicates medial meniscus injury-related changes and facilitates the examination of PTOA progression from the initiation to late stages. These features have enhanced their utility in therapeutic and mechanistic studies.

Specific models, such as monosodium iodoacetate (MIA)-induced OA, which produces pain-depressed wheel running[

35], have been used to assess knee joint function. Treadmill behavior is useful for preclinical behavioral assessments of chronic pain and inflammation[

16]. Traditional PTOA models, including chemically induced methods such as MIA-induced osteoarthritis, are useful for assessing pain, but fail to capture the complete clinical spectrum of osteoarthritis, particularly structural degeneration. The MMM overcomes these limitations by integrating functional validations, such as treadmill exhaustion tests, allodynia assessments, and histological analysis, within a single experimental setup. This comprehensive approach allows researchers to simultaneously study both functional impairments and underlying structural damage.

Innovative aspects of the MMM model include reproducibility, simplified surgical procedure, and versatility for functional studies. It minimizes the non-physiological inflammatory changes observed in other models and promotes a more natural progression of PTOA-like pathology. Its minimally invasive nature not only reduces variability, but also enhances consistency in experimental outcomes. Functional assessments, such as the treadmill exhaustion test and Von Frey hair test, demonstrated substantial deficits in running time and distance, as well as enhanced sensitivity, in the MMM group compared to controls. These findings indicated that the MMM model can effectively elicit functional alterations associated with PTOA. Histological analysis with safranin-O staining for proteoglycan revealed lower staining and higher OARSI scores in the MMM group, validating model-induced structural alterations.

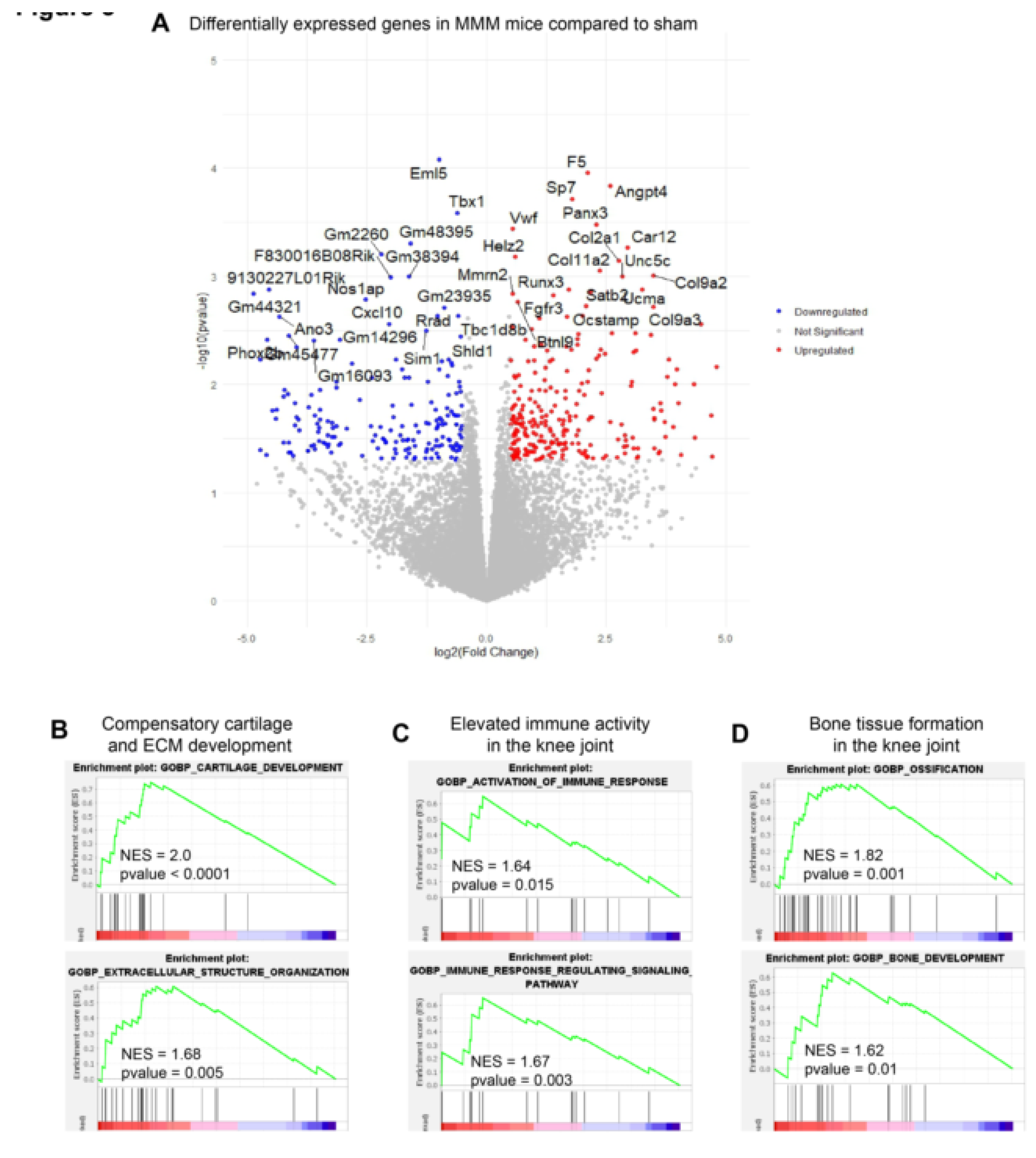

Gene expression analysis using RNA sequencing followed by downstream gene ontology analysis demonstrated that the MMM model reflects inflammatory OA-related molecular alterations. Moreover, there was a compensatory enrichment of cartilage growth gene sets, which might be offset by a larger enrichment of activated immune responses and bone tissue formation in the mouse knee joint. This mitigation was corroborated by our RNA-seq analysis, which was performed 4 months after MMM surgery and revealed that biological processes linked to activated immune response and ossification were strongly enriched in the gene ontology analysis. Further studies are needed to evaluate this model under various conditions, including aging, obesity, and inflammation, and to better understand its translational relevance under specific conditions.

Beyond PTOA, the MMM model has the potential for broader applications, such as exploring osteochondral progenitors, stem cells, and cartilage-bone metabolism. It offers a promising platform for investigating biomarkers and therapeutic agents, including novel chondroprotective candidates such as lysyl oxidase-like 2[

7,

8,

9]. Additionally, its ability to study collagen degradation and repair mechanisms makes it highly applicable in osteoarthritis research.

Although the MMM model has several benefits, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. The model's application to various types of OA and its long-term implications warrant further exploration. Future research should focus on refining the MMM model and investigating its potential for large-scale investigations and clinical applications.

In conclusion, the MMM model bridges the existing gaps in preclinical studies by combining structural and functional analyses within a single experimental framework. This study provides valuable insights into PTOA mechanisms and opens new avenues for the development of diagnostic tools and therapeutic interventions. Optimizing this model for aging mice and enhancing its relevance to human osteoarthritis will further strengthen its role in translational research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

The specific contributions of this study are as follows. Conception and design of the study: Rajnikant Dilip Raut and Manish V. Bais. Acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation: Rajnikant Dilip Raut and Manish V. Bais. Drafting of the article and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Manish V. Bais. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical Compliance

All procedures performed in the mouse study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee with IACUC (AN-15387).

Acknowledgments

Support: The authors acknowledge that NIH/NIDCR grants R01DE031413 and R03DE025274 to Manish V. Bais. We acknowledge the help of the Metabolic Phenotyping Core, Boston University, and Francesca Seta for their help with the analysis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the content of this manuscript.

Financial Interests

The authors declare that they have no financial interests regarding the content of this manuscript.

References

- Losina, E.; Weinstein, A.M.; Reichmann, W.M.; Burbine, S.A.; Solomon, D.H.; Daigle, M.E.; Rome, B.N.; Chen, S.P.; Hunter, D.J.; Suter, L.G.; et al. Lifetime risk and age at diagnosis of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the US. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013, 65, 703-711. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Iversen, M.D.; McAlindon, T.; Harvey, W.F.; Wong, J.B.; Fielding, R.A.; Driban, J.B.; Price, L.L.; Rones, R.; Gamache, T.; et al. Assessing the comparative effectiveness of Tai Chi versus physical therapy for knee osteoarthritis: design and rationale for a randomized trial. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014, 14, 333. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, U.S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Niu, J.; Zhang, B.; Felson, D.T. Increasing prevalence of knee pain and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: survey and cohort data. Ann Intern Med 2011, 155, 725-732. [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, R.C.; Jain, L.; Dalbeth, N. Re-thinking osteoarthritis pathogenesis: what can we learn (and what do we need to unlearn) from mouse models about the mechanisms involved in disease development. Arthritis Res Ther 2023, 25, 59. [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, N.C.; Curry, K.F.; Steinberg, J.; Dewhurst, H.; Komla-Ebri, D.; Mannan, N.S.; Adoum, A.T.; Leitch, V.D.; Logan, J.G.; Waung, J.A.; et al. Accelerating functional gene discovery in osteoarthritis. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 467. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, R.; Wang, Y.; Jian, F.; Long, H.; Lai, W. Delay in articular cartilage degeneration of the knee joint by the conditional removal of discoidin domain receptor 2 in a spontaneous mouse model of osteoarthritis. Ann Transl Med 2020, 8, 1178. [CrossRef]

- Tashkandi, M.M.; Alsaqer, S.F.; Alhousami, T.; Ali, F.; Wu, Y.C.; Shin, J.; Mehra, P.; Wolford, L.M.; Gerstenfeld, L.C.; Goldring, M.B.; et al. LOXL2 promotes aggrecan and gender-specific anabolic differences to TMJ cartilage. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 20179. [CrossRef]

- Alshenibr, W.; Tashkandi, M.M.; Alsaqer, S.F.; Alkheriji, Y.; Wise, A.; Fulzele, S.; Mehra, P.; Goldring, M.B.; Gerstenfeld, L.C.; Bais, M.V. Anabolic role of lysyl oxidase like-2 in cartilage of knee and temporomandibular joints with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2017, 19, 179. [CrossRef]

- Tashkandi, M.; Ali, F.; Alsaqer, S.; Alhousami, T.; Cano, A.; Martin, A.; Salvador, F.; Portillo, F.; L, C.G.; Goldring, M.B.; et al. Lysyl Oxidase-Like 2 Protects against Progressive and Aging Related Knee Joint Osteoarthritis in Mice. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [CrossRef]

- Glasson, S.S.; Blanchet, T.J.; Morris, E.A. The surgical destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM) model of osteoarthritis in the 129/SvEv mouse. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2007, 15, 1061-1069. [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Huang, L.; Welch, I.; Norley, C.; Holdsworth, D.W.; Beier, F.; Cai, D. Early Changes of Articular Cartilage and Subchondral Bone in The DMM Mouse Model of Osteoarthritis. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 2855. [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, B.A.; Guilak, F.; Lockwood, K.A.; Olson, S.A.; Pitsillides, A.A.; Sandell, L.J.; Silva, M.J.; van der Meulen, M.C.; Haudenschild, D.R. Non-invasive mouse models of post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2015, 23, 1627-1638. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.S.; Park, I.Y.; Hong, J.I.; Kim, J.R.; Kim, H.A. Comparison of joint degeneration and pain in male and female mice in DMM model of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2021, 29, 728-738. [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.L.; Blanchet, T.J.; Peluso, D.; Hopkins, B.; Morris, E.A.; Glasson, S.S. Osteoarthritis severity is sex dependent in a surgical mouse model. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2007, 15, 695-700. [CrossRef]

- Gowler, P.R.W.; Mapp, P.I.; Burston, J.J.; Shahtaheri, M.; Walsh, D.A.; Chapman, V. Refining surgical models of osteoarthritis in mice and rats alters pain phenotype but not joint pathology. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0239663. [CrossRef]

- Cobos, E.J.; Ghasemlou, N.; Araldi, D.; Segal, D.; Duong, K.; Woolf, C.J. Inflammation-induced decrease in voluntary wheel running in mice: a nonreflexive test for evaluating inflammatory pain and analgesia. Pain 2012, 153, 876-884. [CrossRef]

- Fentz, J.; Kjobsted, R.; Birk, J.B.; Jordy, A.B.; Jeppesen, J.; Thorsen, K.; Schjerling, P.; Kiens, B.; Jessen, N.; Viollet, B.; et al. AMPKalpha is critical for enhancing skeletal muscle fatty acid utilization during in vivo exercise in mice. FASEB J 2015, 29, 1725-1738. [CrossRef]

- Stockl, S.; Taheri, S.; Maier, V.; Asid, A.; Toelge, M.; Clausen-Schaumann, H.; Schilling, A.; Grassel, S. Effects of intra-articular applied rat BMSCs expressing alpha-calcitonin gene-related peptide or substance P on osteoarthritis pathogenesis in a murine surgical osteoarthritis model. Stem Cell Res Ther 2025, 16, 117. [CrossRef]

- Muschter, D.; Fleischhauer, L.; Taheri, S.; Schilling, A.F.; Clausen-Schaumann, H.; Grassel, S. Sensory neuropeptides are required for bone and cartilage homeostasis in a murine destabilization-induced osteoarthritis model. Bone 2020, 133, 115181. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Miller, L.M.; Patel, J.M.; Meadows, K.D.; Eby, M.R.; Saleh, K.S.; Martin, A.R.; Stoeckl, B.D.; Hast, M.W.; Elliott, D.M.; et al. Transection of the medial meniscus anterior horn results in cartilage degeneration and meniscus remodeling in a large animal model. J Orthop Res 2020, 38, 2696-2708. [CrossRef]

- Doyran, B.; Tong, W.; Li, Q.; Jia, H.; Zhang, X.; Chen, C.; Enomoto-Iwamoto, M.; Lu, X.L.; Qin, L.; Han, L. Nanoindentation modulus of murine cartilage: a sensitive indicator of the initiation and progression of post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2017, 25, 108-117. [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, C.; Chanalaris, A.; Knights, C.; Ismail, H.; Sacitharan, P.K.; Gentry, C.; Bevan, S.; Vincent, T.L. Nociceptive Sensitizers Are Regulated in Damaged Joint Tissues, Including Articular Cartilage, When Osteoarthritic Mice Display Pain Behavior. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016, 68, 857-867. [CrossRef]

- Geraghty, T.; Ishihara, S.; Obeidat, A.M.; Adamczyk, N.S.; Hunter, R.S.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Lee, H.; Ko, F.C.; Malfait, A.M.; et al. Acute systemic macrophage depletion in osteoarthritic mice alleviates pain-related behaviors and does not affect joint damage. Arthritis Res Ther 2024, 26, 224. [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, A.M.; Kim, S.Y.; Burt, K.G.; Hu, B.; Li, J.; Ishihara, S.; Xiao, R.; Miller, R.E.; Little, C.; Malfait, A.M.; et al. Recommendations For a Standardized Approach to Histopathologic Evaluation of Synovial Membrane in Murine Models of Experimental Osteoarthritis. bioRxiv 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, L.C.; Cooper, E.S.; Hetzendorfer, K.M.; Warren, G.L.; Chang, Y.H.; Willett, N.J. Effects of treadmill running and limb immobilization on knee cartilage degeneration and locomotor joint kinematics in rats following knee meniscal transection. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019, 27, 1851-1859. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.P.; Lee, Y.S.; Choe, Y.; Kim, K.T.; Song, G.J.; Hwang, S.C. Knee osteoarthritis accelerates amyloid beta deposition and neurodegeneration in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Mol Brain 2023, 16, 1. [CrossRef]

- Gil Alabarse, P.; Chen, L.Y.; Oliveira, P.; Qin, H.; Liu-Bryan, R. Targeting CD38 to Suppress Osteoarthritis Development and Associated Pain After Joint Injury in Mice. Arthritis Rheumatol 2023, 75, 364-374. [CrossRef]

- Willcockson, H.; Ozkan, H.; Arbeeva, L.; Mucahit, E.; Musawwir, L.; Longobardi, L. Early ablation of Ccr2 in aggrecan-expressing cells following knee injury ameliorates joint damage and pain during post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2022, 30, 1616-1630. [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Cho, D.; Kim, S.K.; Chun, J.S. STING mediates experimental osteoarthritis and mechanical allodynia in mouse. Arthritis Res Ther 2023, 25, 90. [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.E.; Tran, P.B.; Ishihara, S.; Syx, D.; Ren, D.; Miller, R.J.; Valdes, A.M.; Malfait, A.M. Microarray analyses of the dorsal root ganglia support a role for innate neuro-immune pathways in persistent pain in experimental osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2020, 28, 581-592. [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, E.; Cavanagh, L.; Fong-Yee, C.; Tuckermann, J.; Chen, D.; Little, C.B.; Seibel, M.J.; Zhou, H. Deletion of the chondrocyte glucocorticoid receptor attenuates cartilage degradation through suppression of early synovial activation in murine posttraumatic osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2023, 31, 1189-1201. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, K.M.; Weaver, S.R.; Zars, E.L.; Tschumperlin, D.J.; Westendorf, J.J. Inhibition of Phlpp1 preserves the mechanical integrity of articular cartilage in a murine model of post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2024, 32, 680-689. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Luo, L.; Gui, T.; Yu, F.; Yan, L.; Yao, L.; Zhong, L.; Yu, W.; Han, B.; Patel, J.M.; et al. Targeting cartilage EGFR pathway for osteoarthritis treatment. Sci Transl Med 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Akkiraju, H.; Srinivasan, P.P.; Xu, X.; Jia, X.; Safran, C.B.K.; Nohe, A. CK2.1, a bone morphogenetic protein receptor type Ia mimetic peptide, repairs cartilage in mice with destabilized medial meniscus. Stem Cell Res Ther 2017, 8, 82. [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, G.W.; Mercer, H.; Cormier, J.; Dunbar, C.; Benoit, L.; Adams, C.; Jezierski, J.; Luginbuhl, A.; Bilsky, E.J. Monosodium iodoacetate-induced osteoarthritis produces pain-depressed wheel running in rats: implications for preclinical behavioral assessment of chronic pain. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2011, 98, 35-42. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).