1. Introduction

Articular cartilage repair remains a hot topic in clinical and surgical fields alongside the fundamental research. However, to date no intervention or technique to repair hyaline cartilage had demonstrated satisfying efficacy especially for long-term results [

1,

2,

3]. In this regard advancement in tissue engineering and cellular therapies are amongst the most promising modalities.

The use of an optimal animal model is critical not only to improve our knowledge of newly proposed therapies but is also key prior to a clinical translation [

4]. The ideal model should ultimately offer a joint anatomy and proportions similar to those of a human knee, relatively easy to do surgery on in most research facilities. This is important when considering the age and size of the animal at different stages of skeletal maturity and healing and regenerative potentials of the studied pathology. Moreover, the animals of this model should be suitable for several months’ follow-up while being cost effective. On an equally important aspect, in accordance with the 3R principals (Replace, Reduce, Refine), the animal model needs to fulfill several requirements dictated by the purpose of the study and the capacity of the host research facility [

5].

Several large animal models have been described and used in the literature for cartilage research [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. The goat model is commonly used in cartilage grafting for its surgical accessibility, knee anatomy and easy handling [

8,

11]. The equine model has been used in preclinical studies as a comparative with human due to cartilage similarities in thickness, tensile forces, and age-related cartilage elasticity [

9,

12]. Nevertheless, it is of a high cost for hosting and needs a large, specialized facility in terms of spaces allocated for each animal and human resources to care for them.

Domestic pig (DP), large white pig, was primary chosen for the anatomical resemblance to the human knee, large joint dimensions and affordability in terms of financial cost and availability at local production sites [

7]. Unfortunately, the heavy weight at the age of skeletal maturity (up to 200kg), represents a major obstacle, making it a difficult task for keepers, anesthesia team and surgeons to handle.

Göttingen mini-pigs (G-MP), are an interesting model because the skeletally mature adult animal has a maximum weight of 45- 50kg. This limited weight gain allows for easier handling by the host facility, the possibility to increase sample size without overloading the animal caregivers.

The aim of the study was demonstrate the feasibility of a two-stage cartilage surgery with first cartilage harvesting and then implantation using both pig models. Different topics were addressed at each step; first, analyzing intra-operative exposure of the trochlea and the condyle for simulated cartilage lesions to be treated; second, post-mortem, analyzing patellofemoral and femoral condylar joint morphology and cartilage thickness in both models, and compare the postoperative handling. We investigated G-MP as preclinical study animal model to see whether it represents a reliable and an adequate model in terms of animal weight, size and joint suitability for articular cartilage surgical studies. Our hypothesis was that the G-MP model is suitable for cartilage research and comparable to DP in terms of surgical anatomy, with major advantages in handling.

2. Materials and Methods

The animals included in this study were originally used for a preclinical safety and efficacy study on autologous cartilage treatment for focal chondral lesions with the results to are published separately [

13]. All subjects underwent a two-staged surgery on the right distal femur, with 5 to 6 weeks of interval in between and were sacrificed at 2 weeks, 3 months or 6 months follow-up. Animal surgeries were performed in accordance with the guidelines for the Geneva cantonal veterinary authorities, and study protocols were approved by the authorities (Ge 14-18).

Animals

The study included six skeletally mature female G-MP aging 17 months and 45kg (SD ± 2kg) of weight at the time of the first surgery. DP were chosen to have similar starting weight and were therefore 5 months old (

Table 1). All animals were weighed at arrival to the research facility, prior to each surgery and prior to euthanasia. All animals included in this study were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions (SPF) and were hosted in an adapted farm up to the surgery where they spent one night pre-operatively and one week post-operatively at the university animal research facility. The animals were hosted in a farm-like facility for their wellbeing throughout the entire follow-up period.

Anesthesia

The animals were pre-medicated in their holding box with Azaperone (Stresnil, 0.1mL/kg, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Belgium) and Midazolam (Dormicum, 0.1mL/kg, Hoffmann-La Roche AG, Switzerland) administrated subcutaneously. An intravenous access was gained through the auricular vein, then general anesthesia was achieved with etomidate (Hypnomidate, 0.25mL/kg, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Belgium), and a standard tracheal tube, size 6.5, was inserted.

General anesthesia was maintained with Sevoflurane® (3%, AbbVie, Denmark) and fentanyl (0.175mL/kg/h, Hameln pharmaceuticals, Germany). Prior to the incision, the animals received prophylactic antibiotics (Penicillinprokain, Ceva Sante Animale, France) 0.03mL/kg.

Surgeries

All animals underwent a two-staged surgical protocol of the right knee using two separate approaches with minimally invasive incisions and arthrotomies.

The operated zone was shaved in theater, alcoholic disinfection (Betaseptic®, Mundipharma, Hamilton/Bermuda, Succursale Basel) three times then a sterile draping was applied.

The first surgery for cartilage harvesting was performed through a superolateral parapatellar approach, incising the lateral retinaculum and the articular joint capsule by sparing the vastus lateralis. The superolateral trochlear facet was exposed and cartilage samples were harvested. This zone was chosen to avoid cartilage harvesting from a load-bearing region and while also avoid overlapping between the harvest site and the intended lesion. This dual approach was meant to minimize the surgical morbidity by accessing the knee joint by the same approach as for cartilage implantation.

The second surgery was performed 5-6 weeks later through a medial parapatellar-tendon approach. The maximum of the trochlear surface was exposed to create two full-thickness cartilage lesions on the medial and lateral trochlear facet each, all approximately 2cm above the trochlear notch and on the medial femoral condyle. Great care was taken that the lesions were at least 5mm distance from each other. Full thickness chondral defects were outlined using a 6mm skin biopsy punch and the cartilage was carefully stripped off using a curette, with caution not to damage the subchondral bone plaque. In the same surgical step, the cultured cartilage cells were implanted.

Postoperative Protocol

Postoperative protocol included weight-adapted anti-inflammatory medications per-os for 3 consecutive days and no weight bearing limiting measures due to the graft requirement of the original study. Animals were kept in the research facility for a week post-operation and examined daily for limping, pain, infection signs and wound healing.

Euthanasia and Descriptive Analysis

All animals were euthanized at different time points to meet the needs of the original study, using terminal dose anesthesia. The four DP were euthanized 2 weeks post second surgery, while three G-MP were euthanized at 3 months and the remaining three at 6 months.

At euthanasia the accessible areas through both incision of the trochlea and the medial femoral condyle from both incisions were marked using an electrical cautery knife to allow for accurate calculation of the visible articular surface. The dimensions of the entire trochlea were obtained by measuring the medial and lateral length and width at its widest. The number of possible separate lesions that can be fitted on the femoral part of the knee joint was evaluated. Cartilage thickness was measured using histological cuts of the lateral facete of trochlea from a healthy cartilage zone.

A macroscopic evaluation of the fully exposed joint, post full capsulotomy was performed by the same investigators and potential complications were looked for such as overlap of donor site and recipient site cartilage degeneration, synovitis and ectopic tissue growth.

For microscopic evaluation samples were prepared for histology readout. After soft tissue removal, the distal femur was separated from its shaft using a bone saw. The samples were fixed in 4% formol for a week then decalcified using formic acid 10% for 2 weeks at room temperature. Then they were cut into 5μm serial sections at using a microtome (Reichert Jung polycot) and mounted on adhesion slides (Thermo Scientific™ SuperFrost Plus™). Before staining the sections were deplasticized in dimetoxyethylacetate and rehydrated. The samples were stained with safranin-O for glycosaminoglycan then fixed with EurKit risin.

Contralateral Knee Comparison

At euthanasia the range of motion between the two knees was recorded with full passive flexion/ extension maneuvers. Then, the left knee underwent identical two approach surgery without graft, and then analyzed for the anatomical features. Post-mortem comparison between the operated and non-operated knee was carried on in terms of cartilage degradation, patellar tendon shortening and differences in range of motion of the knee. The patellar tendon was measured from the distal edge of the patella to its insertion at the proximal tibial tubercule and compared to the contralateral side.

G-MP and DP Comparison

G-MP and DP were compared in terms of distal femur joint dimensions and surgical exposure and accessibility. We documented the number of possible lesions on each trochlear facet, conflict with donor site, cartilage thickness in post-mortem analysis. The weight gain was compared between the two models throughout the study defined time-points (on arrival, prior to each surgery, prior to euthanasia). We also compared the cost of handling and documented unforeseen care and follow-up issues in real time manner as they occurred.

3. Results

3.1. Anatomy and Surgical Approaches

The hind-extremity in both groups was comparable in both groups in terms of joint anatomy and its relation to the animal body as it is high near the trunk and not to be confused with its tibio-talar articulation. The joint morphology resembled the human knee with femoro-tibial compartments, retro-patellar compartment, cruciate ligaments, and menisci. Important difference was noted is the absence of a quadriceps tendon and the attachment of the quadriceps muscle directly on the superior pole of the patella.

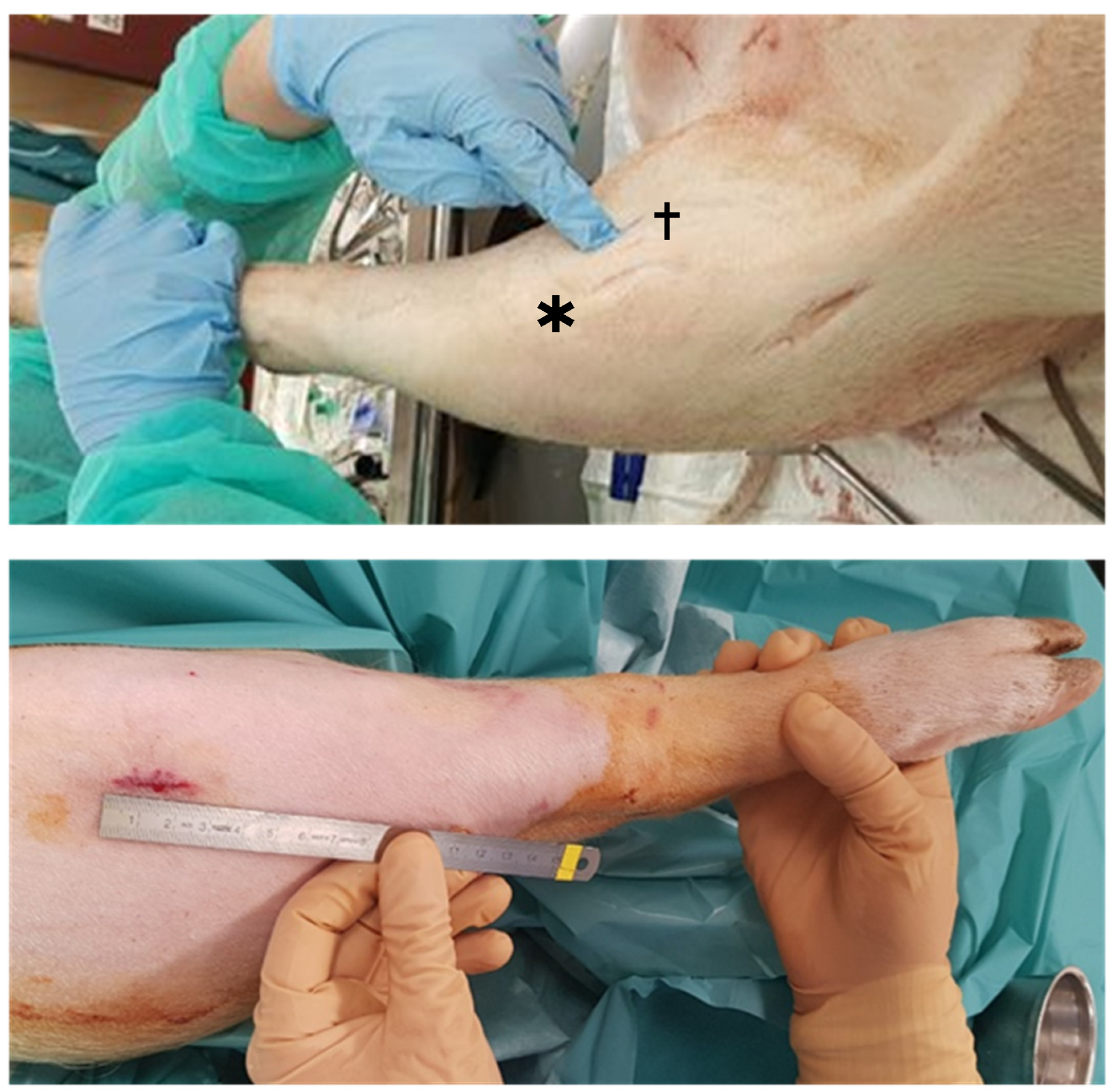

The first surgery used 2cm incision for the superolateral approach which was sufficient to harvest up to 70mg of cartilage from DP and up to 40mg from G-MP (

Figure 1). This allowed for a proper visualization of the proximal lateral aspect of the joint surface, in both models (

Table 1).

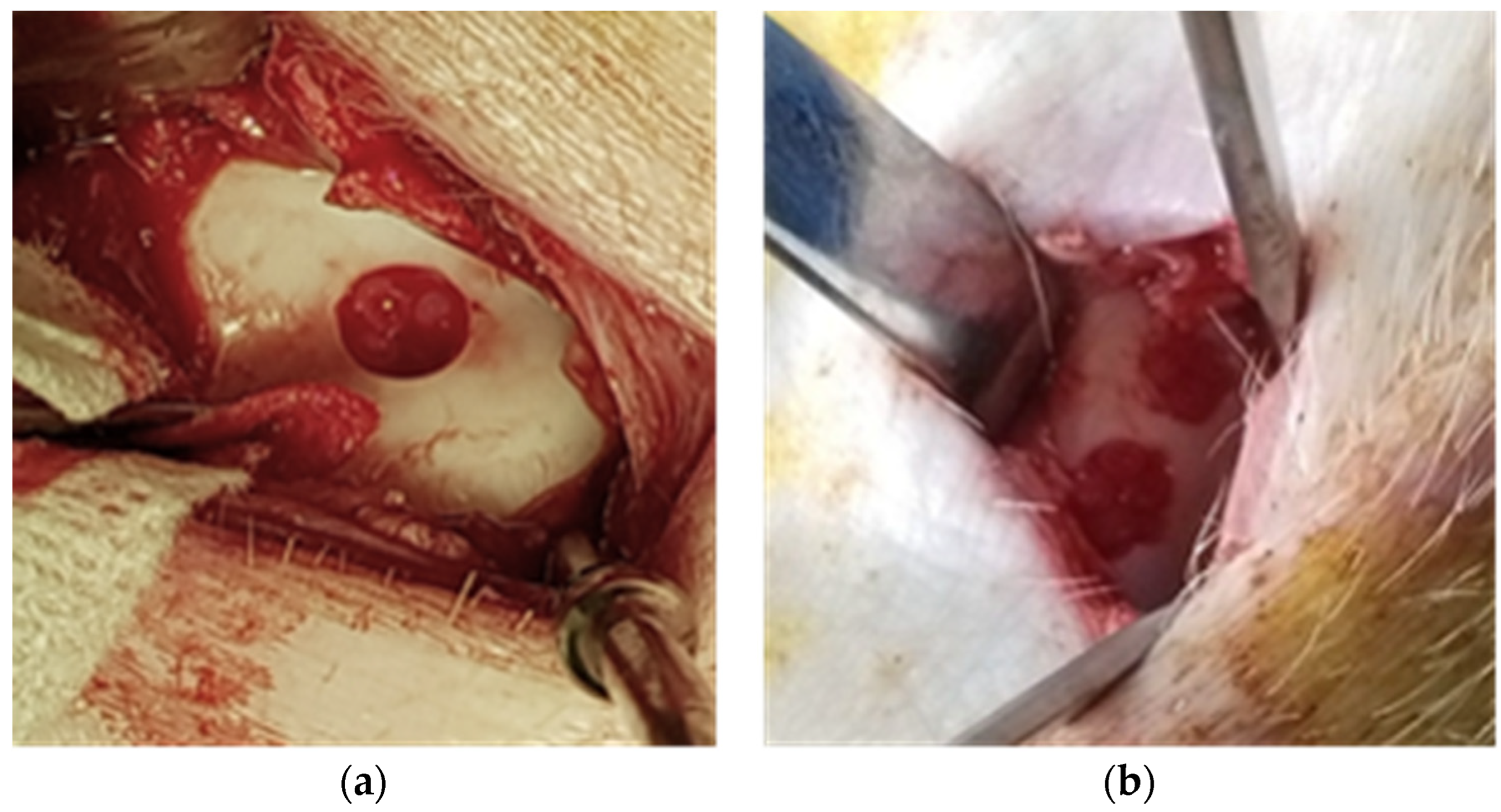

The second surgery used the medial parapatellar-tendon approach, through a slightly larger skin incision (3cm), allowing access of the trochlea and the creation of 4 trochlear lesions and 1 medial condyle lesion (

Figure 2).

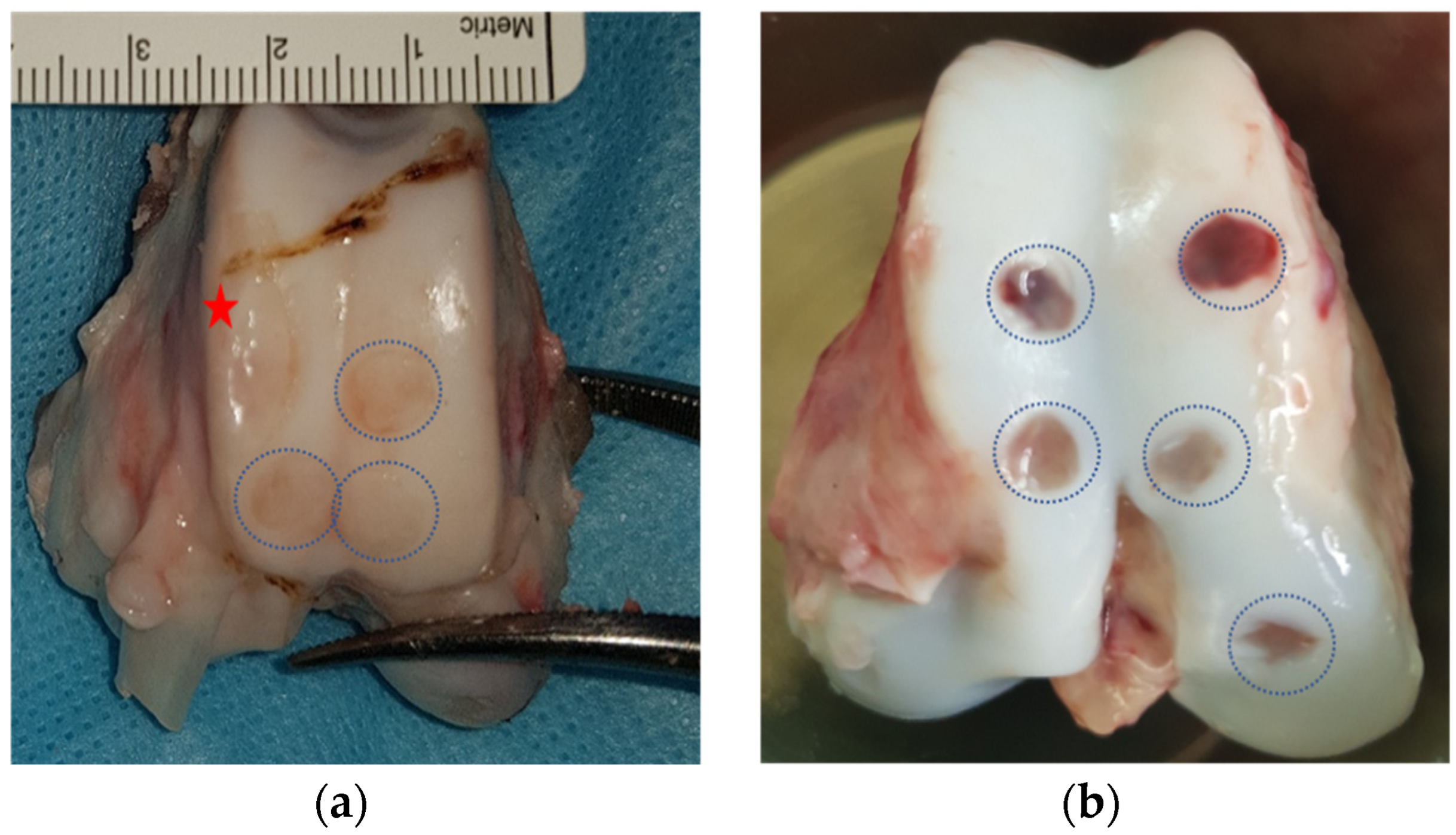

This approach gave enough access to create the planned 4 trochlear lesions without over-lapping and a bridge of at least 5mm between the lesions on the facets, and the medial condyle lesion (

Figure 3). A conflict with the harvest site was noted in 2 out of 6 G-MP leading to the loss of a planned lesion on the proximolateral trochlear facet.

This approach gave access to 63% (SD ± 4.1) with knee extension and 34% (SD ± 13.5) of access to the medial condyle in knee flexion in DP (

Table 1).

3.2. Complications & Morbidity

All animals recovered completely without observed complications. The animals’ mobility was back to normal without limping, and they were able to fully weight bearing by day 3 after both surgeries. There were no wound healing issues with any animal nor - visible joint inflammations.

In post-mortem analysis no degenerative process nor patellar tendon shortening were noticed when comparing both sides.

3.3. Comparison

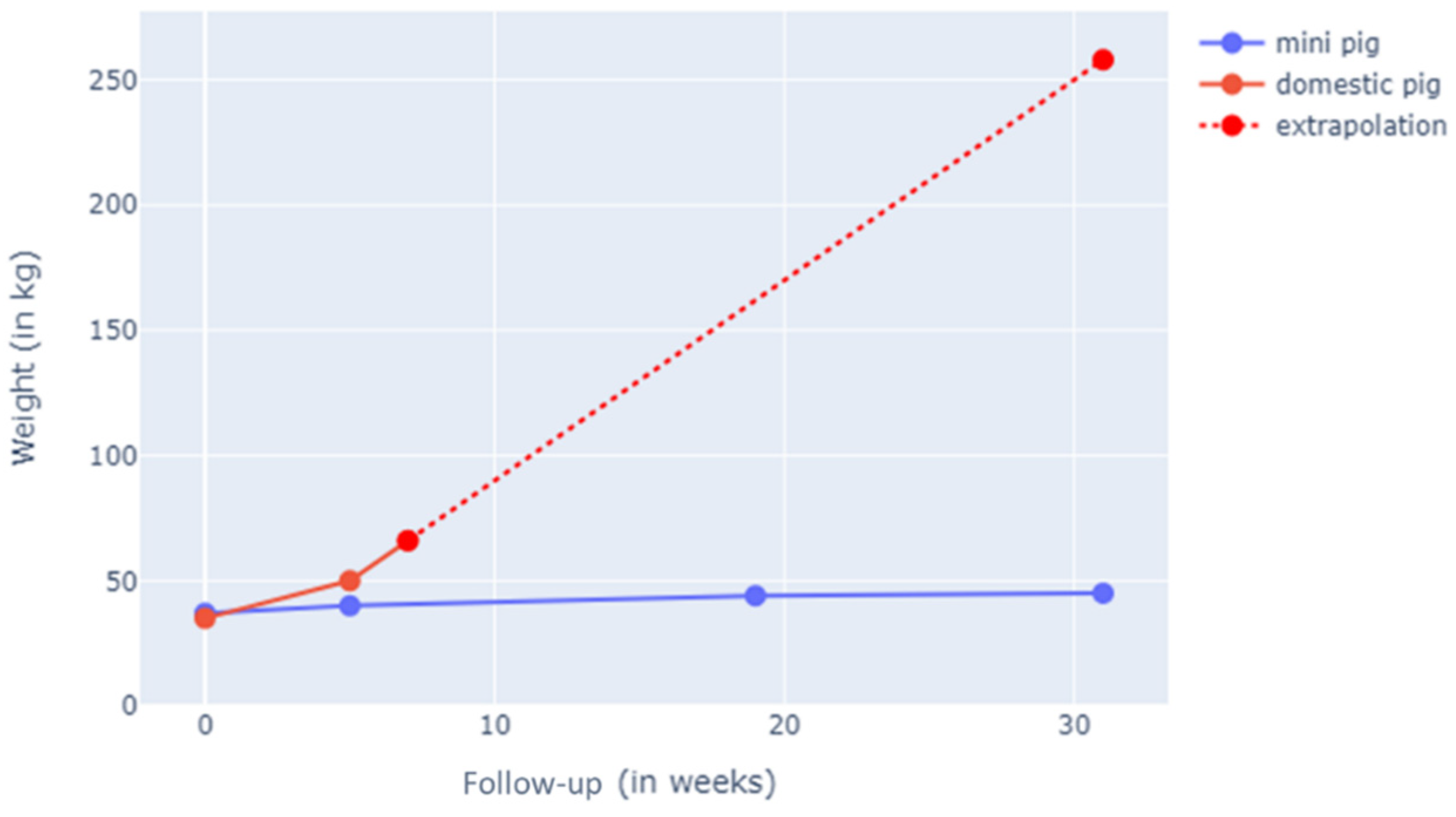

In the living animal weight gain was documented, where both models started at 45kg at the beginning of the study. The study animals were weighed weekly, and their weight-progression was documented. We noted + 0.2 kg/week for G-MP group versus + 4 kg/week in DP group. The G-MP reached a maximum weight of 50kg (SD ± 3kg) at 6 month, where as the DP reached 60kg (SD ± 2kg) at 2 weeks of follow-up (

Figure 4).

Joint evaluation in peri-euthanasia showed a conserved range of motion. This was monitored by two observers (PT, HK) for all animals just prior euthanasia and no difference in passive flexion and extension were noticed between both groups when compared to the contralateral knee. Post-mortem joint measurements showed a larger joint in the DP compared to G-MP (

Table 1) at a comparable weight point.

Vascularized cartilage was observed in domestic pigs which is thought to be due to their young age but was absent in the adult G-MP.

The histological analysis showed the differences in cartilage thickness between the G-MP (< 1mm) and DP (>2mm) within a cross-sectional segment of the joint facet (

Figure 5).

Post-mortem, joint morphology and cartilage macroscopic evaluation showed no signs of inflammation and no changes on the rest of the joint cartilage that was not subjected to lesion creation or harvest. Narrow trochlea in G-MP allows only 4 lesions of 6 mm diameter without overlap, while domestics permit to increase number or size of lesions (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

The main finding of the study is that the G-MP is adequate and reliable large animal model for testing novel cartilage therapies. This valuable model offers some unique opportunities to explore research questions in biomechanics and biology [

6,

7,

14,

15]. The two approaches to the knee in both groups did not generate limping or altered weight-bearing for more than two days post-operatively. Scarring was minimal by the time of the second surgery and adhesions were minimal by the time of euthanasia. The advantages of the G-MP model leis in its size and weight remaining constant in the adult animals allowing for long term follow-up studies. The use of adult animals means the cartilage is mature without vascularization as noted in the young DP group.

Our results highlight the main differences in the knee joint anatomy in G-MP compared to DP. In G-MP the joint is smaller, and the trochlea is narrower, which can lead to a conflict between the harvesting site and the defect site. In addition, in G-MP the articular surface was more difficult to expose leading to additional technical challenges for the surgeons to comfortably treat and control multiple lesions. The articular cartilage thinness in G-MP can be somehow a challenge to stabilize a graft within a limited lesion. The above listed characteristics in the G-MP did not prevent our group from achieving the desired results in creating and grafting multiple lesions in a study with a 6-month follow-up period [

13].

The morphological and histological features of both groups showed no notable degradation of the joints after successive surgeries using 2 distinct approaches within 5 weeks. Comparable to what was previously reported in studies on the G-MP we found no degenerative changes with our 5 lesions per knee when compared to 1 or 2 lesions [

15].

The direct attachment of the muscle on the patella makes the proximal trochlear surface or the patellar surface difficult to access without extensive damage to the muscle. This anatomical characteristic makes this model more difficult or rather impossible to use for retropatellar lesion studies or kissing lesions.

The limitation of the G-MP model from a financial aspect is that the DP is more affordable especially for larger study samples, as the initial cost of G-MP per animal is considerably high (2000€ /G-MP vs 300€ /DP) plus the shipping from specialized breeding facilities that are not available in many countries.

5. Conclusions

Mini-pig model allows for multiple lesions per knee and for long term follow up without much strain on animals or host structure. However, it is important to note that its thin cartilage and a narrow trochlea might be somehow a challenge depending of the tested treatment method. Domestic pigs, have a larger joint surface and thicker cartilage, making it more comparable to the human knee, but their adult weight makes them less suitable for studies needing long-term follow ups. Both superolateral and medial approaches can be used in both groups without noticeable risk of joint degeneration nor animal discomfort. Altogether, this study not only provides a methodology for mini-pig 2-step surgery but also present mini-pigs as a relevant animal model for cartilage study.

Author Contributions

HK and PMT designed the experiment and excuted the surgeries, VT designed the laboratory protocol and evaluated the results. HK wrote the manuscript amd PMT and VT reviewed the paper pre-submission.

Funding

Vanarix SA, Centre Assal for foot and ankle surgery, Swiss Foot and Ankle Society (SFAS).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Swiss cantonal veterinary authority approval for animal use in medical research Ref. (GE 14/18).

Data Availability Statement

All additional data and information regarding the methodology and results are available with the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the animal research facility and the team of Professor Walid Habre and the diagnostic facility from the Geneva University Hospitals.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Riboh, J.C., et al., Comparative efficacy of cartilage repair procedures in the knee: a network meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 2017. 25(12): p. 3786-3799.

- Belk, J.W. and E. McCarty, Editorial Commentary: Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation Versus Microfracture for Knee Articular Cartilage Repair: We Should Focus on the Latest Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation Techniques. Arthroscopy, 2020. 36(1): p. 304-306.

- Hoburg, A., et al., Matrix-Associated Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation with Spheroid Technology Is Superior to Arthroscopic Microfracture at 36 Months Regarding Activities of Daily Living and Sporting Activities after Treatment. Cartilage, 2020: p. 1947603519897290.

- Moran, C.J., et al., The benefits and limitations of animal models for translational research in cartilage repair. J Exp Orthop, 2016. 3(1): p. 1.

- Allen, M.J., et al., Ethical use of animal models in musculoskeletal research. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 2017. 35(4): p. 740-751.

- Pfeifer, C.G., et al., Age-Dependent Subchondral Bone Remodeling and Cartilage Repair in a Minipig Defect Model. Tissue Eng Part C Methods, 2017. 23(11): p. 745-753.

- Gutierrez, K., et al., Efficacy of the porcine species in biomedical research. Front Genet, 2015. 6: p. 293.

- Xia, D., et al., Tissue-engineered trachea from a 3D-printed scaffold enhances whole-segment tracheal repair in a goat model. J Tissue Eng Regen Med, 2019. 13(4): p. 694-703.

- McIlwraith, C.W., et al., Equine Models of Articular Cartilage Repair. Cartilage, 2011. 2(4): p. 317-26.

- Lu, Z., et al., A Novel Synthesized Sulfonamido-Based Gallate-JEZTC Blocks Cartilage Degradation on Rabbit Model of Osteoarthritis: An in Vitro and in Vivo Study. Cell Physiol Biochem, 2018. 49(6): p. 2304-2319.

- Bekkers, J.E., et al., One-stage focal cartilage defect treatment with bone marrow mononuclear cells and chondrocytes leads to better macroscopic cartilage regeneration compared to microfracture in goats. Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 2013. 21(7): p. 950-6.

- Cone, S.G., P.B. Warren, and M.B. Fisher, Rise of the Pigs: Utilization of the Porcine Model to Study Musculoskeletal Biomechanics and Tissue Engineering During Skeletal Growth. Tissue Eng Part C Methods, 2017. 23(11): p. 763-780.

- Kutaish, H., et al., Articular Cartilage Repair After Implantation of Hyaline Cartilage Beads Engineered From Adult Dedifferentiated Chondrocytes: Cartibeads Preclinical Efficacy Study in a Large Animal Model. Am J Sports Med, 2023. 51(1): p. 237-249.

- Hsieh, Y.H., et al., Healing of Osteochondral Defects Implanted with Biomimetic Scaffolds of Poly(epsilon-Caprolactone)/Hydroxyapatite and Glycidyl-Methacrylate-Modified Hyaluronic Acid in a Minipig. Int J Mol Sci, 2018. 19(4).

- Christensen, B.B., et al., Experimental articular cartilage repair in the Göttingen minipig: the influence of multiple defects per knee. J Exp Orthop, 2015. 2(1): p. 13.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).