1. Introduction

Articular cartilage has a crucial role in the joint by absorbing pressure, rendering it elastic to compression and flexion. It comprises various connective and supportive elements such as proteoglycans and collagens and is characterized by a scarcity of blood vessels [

1]. Nutrient diffusion from synovial fluid is the primary means of nourishing cartilage tissue. However, when localized pressure, often due to abnormal loading, exceeds certain limits, the access to these nutrients may become compromised or disrupted. In individuals who engage in regular physical activity, the cartilage must endure loads equivalent to 10 to 20 times their body weight [

2].

Hyaline articular cartilage exhibits limited inherent self-repair capabilities. Traumatic or degenerative damage typically results in the development of repair tissue that possesses inferior structural and biomechanical attributes compared to healthy articular cartilage [

2]. Chondrocytes, the cartilage cells, are unable to efficiently multiply and migrate for the generation of high-quality repair tissue, whether the damage is superficial or deep [

3]. The current focus in managing symptomatic cartilage defects in the knee joint revolves around the repair of the articular surface, the restoration of joint balance, and, ultimately, the prevention of osteoarthritis progression.

In the late 1990s, commonly employed therapeutic options included surface debridement procedures like chondral shaving, abrasion chondroplasty, and subchondral perforation, as well as soft tissue arthroplasty procedures utilizing perichondral or periosteal grafts. However, none of these methods yielded normal, hyaline-like cartilage tissue. More recent techniques based on bone marrow stimulation or cell application have since been introduced. Microfracture (MFX) stands as a widely adopted bone marrow stimulation strategy, and a range of cell-based restoration techniques utilizing adult or juvenile, autograft or allograft cartilage sources, along with chondrocyte and nonchondrocyte options, are now available [

4].

Historically, the gold standard for repairing cartilage defects has been Matrix-induced Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (MACI). Dr. Lars Peterson pioneered this treatment method in 1985, which initially faced skepticism but later achieved notable successes in 1989. In 2000, the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence did not recommend routine use of the procedure due to a lack of well-designed studies, but it was eventually confirmed in 2005 [

5]. In MACI, cartilage cells are harvested in a first surgical procedure, cultivated in the laboratory, and then implanted in a second procedure. The two-step MACI approach incurs significant costs associated with multiple surgeries and cell expansion in the laboratory. MACI’s ability to improve clinical outcomes is now supported by numerous studies [

6]. The rate of surgical technical errors has significantly decreased from the first to the second generations of this technique (from 26% to 0.5%), and 5-year survival rates currently stand at 78% [

7]. It’s now evident that factors such as lesion size, prior disease, surgical course, and post-treatment symptoms play significant roles in survival rates [

8].

An alternative approach to treating cartilage lesions is the one-stage matrix-based treatment known as Autologous Matrix-Induced Chondrogenesis (AMIC), developed in 20058 [

9,

10]. In this technique, a matrix is implanted after microfracturing has been performed. The matrix provides a temporary structure to support cell migration and cartilage formation. This contrasts with Matrix-induced Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation treatment, where intact cartilage is arthroscopically removed from an unaffected area of the damaged cartilage in a first surgical procedure and then cultivated on a matrix in vitro in a second step [

11].

In AMIC, periosteal hypertrophy may occur between three and seven months after surgery in 10% to 25% of cases, often necessitating revision surgery.12 Nonetheless, AMIC offers several notable advantages, being more effective than MFX and more cost-effective than MACI [

13].

Another emerging technique that has garnered significant interest for treating cartilage lesions is Minced Cartilage Implantation (MCI). In 1983, Albrecht, Roessner, and Zimmermann first described the treatment of osteochondral lesions with autologous chondral fragments and fibrin glue [

14]. Articles describing similar techniques have proliferated over the last five years. Preclinical in vivo and in vitro data have shown promising results regarding chondrocyte activation through fragmentation [

8,

15]. Cartilage mincing leads to outgrowth, proliferation, and differentiation of articular chondrocytes. Since these proliferation and differentiation processes occur intra-articularly, the cells are consistently exposed to a native physical and biochemical environment [

16].

In the initial descriptions of the MCI technique, cartilage fragments were manually cut into small pieces and then secured in the defect using a membrane or allogeneic fibrin glue. For this open procedure a 5 year follow-up could present positive patient related outcomes and low complication rates [

17]. This technique has since evolved towards an arthroscopic, entirely autologous approach, with the first technical notes published by Schneider and Salzmann in 2020 [

8].

Although the three procedures (MACI, AMIC and MIC) differ in technical aspects, time and cost as previously described, they have all shown good outcomes in the past. Nevertheless, it is worth investigating whether a direct comparison of the three procedures reveals any significant differences in the results reported by patients. To date, no study has directly compared the procedures against each other. The aim of this study is therefore to compare the three surgical techniques (MACI, AMIC and MIC) with regard on patient reported outcomes of pain and function to make recommendations for treatment guidelines in clinical practice.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective match-pair study included 48 patients who had been treated with AMIC, MACI or MCI for cartilage lesions in the knee between 2016 and 2021. Local ethical committee of Hamburg approval (2021-10018-BOff) was obtained prior to initiation and informed consent was signed by all participants prior to being included into the analysis.

2.1. Surgical Procedures

2.1.1. MACI

The surgical procedure using MACI involved two main stages:

First, chondral biopsies were harvested arthroscopically from a non-weightbearing area of the knee using a trephine. Three cylinders were collected and sent to a manufacturing facility, where autologous chondrocytes were expanded in vitro (2-8 million cells/mL). The production process took approximately 24 ± 5 days.

In the second stage, the defect was prepared to ensure a clean, stable, and dry surface. Then, a special hydrogel was applied via a dual-chamber syringe system, simultaneously injecting two components—a chondrocyte suspension and a crosslinker. The hydrogel solidifies in situ within 1-3 minutes, anchoring the cells without additional fixation. Last, the surgeon evaluated implant stability by moving the joint within its physiological range before wound closure. This minimally invasive approach can be performed arthroscopically or via a mini-arthrotomy and ensures precise defect filling with minimal invasiveness.

2.1.2. AMIC

The AMIC procedure was carried out as a one-step procedure. It entailed the insertion of a scaffold into the chondral defect, serving the dual purpose of mechanically stabilizing the cellular clot and encouraging chondrogenic differentiation.5 An injectable chitosan-based scaffold was used. Chitosan, derived from deacetylation of chitin found in the exoskeletons of shellfish and insects, offers biocompatibility and biodegradability, making it a suitable scaffold for the proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes [

18,

19,

20].

In practical terms, the operative technique commences with diagnostic arthroscopy of the knee joint. If necessary, additional procedures such as meniscal repair and ligament reconstruction may be performed within the same setting, preceding the cartilage repair.

The preparation of the gel adheres to the techniques outlined in the manufacturer’s product guide. This involves mixing the buffer solution with the chitosan solution and allowing the mixture to stand for 10 minutes. Subsequently, 5ml of autologous blood is injected into the prepared buffer-chitosan mixture. This gel blood-buffer-chitosan amalgamation is drawn into an application syringe, ready to be applied to the cartilage lesion.

The procedure continues with the debridement of the cartilage defect site using shavers and curettes. Loose chondral tissue is excised to establish stable vertical walls surrounding the defect. The subchondral plate should be preserved while preparing the defect bed. Microfracture is then performed, involving the use of arthroscopic microfracture awls to create lesions at a depth of approximately 4mm. These lesions are spaced 3 to 4mm apart across the surface of the cartilage defect.

Following the drainage of joint fluid, a dry arthroscopy is conducted. The knee’s surface and the cartilage lesion are dried using suction and patties. The injectable scaffold is administered as a viscous gel, targeting horizontal, vertical, and inverted lesions, such as the trochlear, lateral tibial plateau, medial femoral condyle, lateral femoral condyle, and patella. The scaffold is left to solidify within the defect for a period of 5 to 10 minutes. Subsequently, the knee is mobilized, and wet arthroscopy is repeated to confirm the scaffold’s stability in a fluid-filled environment.

2.1.3. Minced Cartilage

The Minced Cartilage procedure was also performed arthroscopically. The technique has been described previously [

8]. Symptomatic full-thickness cartilage defects within the knee joint were addressed, such as the trochlea, femoral condyles, tibial plateau, and the patella. A clinical examination of the affected knee joint, accompanied by an examination under anesthesia, is considered obligatory.

The patient usually is positioned in a supine posture. The use of a tourniquet is advised to establish a bloodless, dry setting for cartilage implantation. Given the necessity for autologous platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in this procedure, venous blood is drawn from the patient, usually from the cubital veins, under meticulously sterile conditions before anesthesia initiation. This precaution is taken to avert potential adverse effects of narcotic substances on the PRP. Typically, a minimum of 10 to 15 mL of pure PRP is collected, and further processing of PRP takes place during the arthroscopy.

Each indicated minced cartilage procedure is initiated via standard arthroscopy of the index knee joint, possibly involving concomitant interventions. The cartilage defect targeted for treatment is thoroughly examined during arthroscopy. The defect is debrided using a small sharp spoon or ringed curette. An optimal debridement technique for cartilage lesions, involving the creation of a stable wall and viable rim. A removal of the calcified layer is done.

The cartilage intended for the procedure can be harvested from the defective cartilage itself, particularly in the case of acute traumatic chondral lesions where the cartilage appears healthy and has recently delaminated. No degenerative cartilage is used for transplantation. The typical and recommended harvest site is the edge of the cartilage defect. If an insufficient amount of cartilage can be collected from the defect’s surroundings, healthy cartilage can be obtained from typical MACI harvest locations, such as the condylar notch. Notably, there is a superior redifferentiation of chondrocytes harvested from the defect’s edge compared to non-weight-bearing regions.

Cartilage is harvested using a 3.0 shaver device which is connected to a collecting device. Thus, Cartilage is harvested, minced into small fragments resembling a paste, and collected immediately. Subsequently, the minced cartilage is mixed with 2 to 3 drops of PRP, resulting in a malleable substance.

The applicator device is loaded with the chips/PRP mixture. Then, 4 ml of PRP is inserted into a specific device to produce autologous thrombin. The chips/PRP paste is applied to the defect to ensure comprehensive coverage. Approximately 50-80% filling, including the surrounding cartilage edge, is typically regarded as sufficient. The consistency of the chips-paste provides initial stability. In the subsequent step, thrombin collected from the devise is applied drop by drop over the chips-paste. The thrombin interacts with the PRP within the chips, generating fibrin that coagulates swiftly, ultimately securing the chips within the cartilage defect. The tissue is sealed with a final layer of fibrin, which was previously mixed, concluding the procedure.

2.2. Rehabilitation

Immediately postoperatively, all patients were remobilized in a straight brace for 48 hours. On the first day after surgery, a continuous passive motion machine was initiated. For the initial six weeks, patients were allowed partial weight-bearing with crutches, and their range of motion was free. After this six-week period, a gradual progression in weight-bearing and range of motion was authorized, ultimately enabling full weight-bearing and unrestricted range of motion around nine weeks after the surgery.

2.3. Patient-Related Outcome Measurements

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) were collected before the surgery and after six-, 12- and 24 months after surgery.

As primary outcome, the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), the pain subscale (KOOS-Pain) and the symptoms (KOOS-Symptoms) subscale of the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) were analyzed. These measures directly reflect the knee joint condition. VAS scores range from 0 (indicating no pain) to 10 (indicating the worst pain) and the KOOS-Pain score ranges from 0% (worst pain) to 100% (no pain) and is reflected by nine out of 42 questions. The KOOS-Symptoms scale is scored the same way with seven questions counting into the score.

As secondary outcomes, the KOOS-Activities of daily living (KOOS-ADL) and KOOS-Quality of live (KOOS-QOL) as well as the Tegner Activity Scale (TAS) for assessing the current activity level were analyzed. These measures reflect on function and activity related to the health status of the joint. The KOOS-Sports and Recreation Subscale was not included because of too many invalid scores overall time points. The KOOS-ADL and KOOS-QOL are also scored from 0 – 100% with the ADL asking for 17 usual activities and the QOL includes 4 questions with regard on the knee joint affecting or not affecting the general quality life.

The TAS is an instrument in which the patient is asked to rate the current level of activity (work, everyday life and sport) on a scale from 0 to 10, each of these scales containing a detailed description of the activities. 0 reflects “Sick leave or disability pension because of knee problems” and 10 “Competitive sports: soccer, football, rugby (national or international elite)”

Additionally, any postoperative complications and reoperations were diligently documented.

2.4. Data Collection and Matching

Data was collected using a prospectively maintained database (Surgical Outcome Measurement System - SOS) that collected patient-related outcome data (PROMs) between 2015 and 2023. The survey was done electronically, and patients were able to answer the required PROMS online after being sent an E-mail with their individual link to the survey at each time point. Additionally, all patients were reminded by telephone to complete the questionnaires on time.

Data of all patients who underwent one of the three treatments was exported from the system. The patients were matched for gender, age, BMI, as well as size and location of the cartilage lesion. In a first step, age, gender, and BMI of treated patients were filtered to find matching pairs and second lesion characteristics were distributed as equally as possible between the groups. The matching process started with the smallest group (MACI, n=16) to which one individual of both remaining groups (AMIC: n=19; MCI: n=84) was matched according to the above-mentioned criteria by a person who was blinded to the outcomes.

2.5. Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (Version 28, IBM) and Microsoft Excel (Version 16). Normal distribution of the data was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. ANOVA with repeated measures and Bonferroni corrected post-hoc tests was used to compare VAS and KOOS scores between groups and relevant time points as well as possible interactions (group*time). Because of not fulfilling the requirements for parametric tests, the Friedmann test was used to compare the TAS Scores for each group respectively between all four time points.

Using G*Power (Version 3.1.9.7), ANOVA with repeated measures, within-between interaction was used for power analysis. With the α-level set to 0.05, three groups, four relevant measurements (pre, 6 months, 1 year, 2 years), an estimated correlation among repeated measures of 0.5 and an estimated effect size (f) of 0.2 (ⴄ² expected to be 0.04) statistical power was estimated to be .83.

In cartilage repair, the patient acceptable state (PASS) is 72.2 for KOOS Pain, 71.5 for KOOS-Symptoms, 86.8 for KOOS-ADL, and 50.0 for KOOS-QOL. Further, a difference greater than 8.3 for KOOS-Pain, 10.7 for KOOS-Symptoms, 8.8 for KOOS-ADL, and 18.8 for KOOS-QOL is considered a clinically important difference (CID) [

21]. The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for the VAS is considered 2.7 [

22].

3. Results

Out of the 48 retrospectively included patients, data on all four time points was available for n=12 (MACI), n=13 (AMIC), and n=15 (MIC) persons per group respectively. Thus, 40 of 48 persons were included into the statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics include the available patient data of each time point. A comprehensive summary of patient attributes and accompanying procedures is presented in

Table 1, while details regarding the characteristics of the cartilage defects can be found in

Table 2. All included patients had isolated cartilage repairing surgery with no accompanying intervention.

3.1. Prior Treatment

13 of 48 patients (27.1 %) had undergone surgery on the index knee within five years prior to the actual cartilage repair surgery. In the MACI group, three osteochondral surgeries and one tibial realignment osteotomy had been performed. In the AMIC group, one osteochondral treatment and one anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction had previously been performed. In the minced cartilage group, there were two previous osteochondral treatments, one meniscal refixation and three ligament reconstructions (2x ACL/1x MFPL).

3.2. Adverse Events

In the MACI group, two people had an indication for a second operation within two years due to ongoing knee pain. In one case, second surgery was performed 15 month after the treatment due to partly insufficient cartilage coverage in the MFC area. In the other case, the patient complained of ongoing pain one year after the operation, which led to an alternative, non-biological treatment of the cartilage lesion being recommended. This person was lost to follow-up after 1 year.

In AMIC group, three patients reported ongoing knee pain. One patient was re-operated after two years because another cartilage lesion had occurred in the trochlea area. Three patients suffered from prolonged knee swelling shortly after the surgery. In all cases this was not caused by any infection and recovered.

In the Minced Cartilage group, one person reported persistent pain one year after surgery which was due to another cartilage defect. A second surgery was recommended for this patient. A second person treated with Minced Cartilage in the LFC area reported ongoing pain The imaging of the area showed sufficient coverage of the lesion and no indication for second surgery. Last, one patient experienced lateral knee ligament rupture of the index knee one year after surgery.

3.3. Patient-Reported Outcome Measurements on Pain and Symptoms

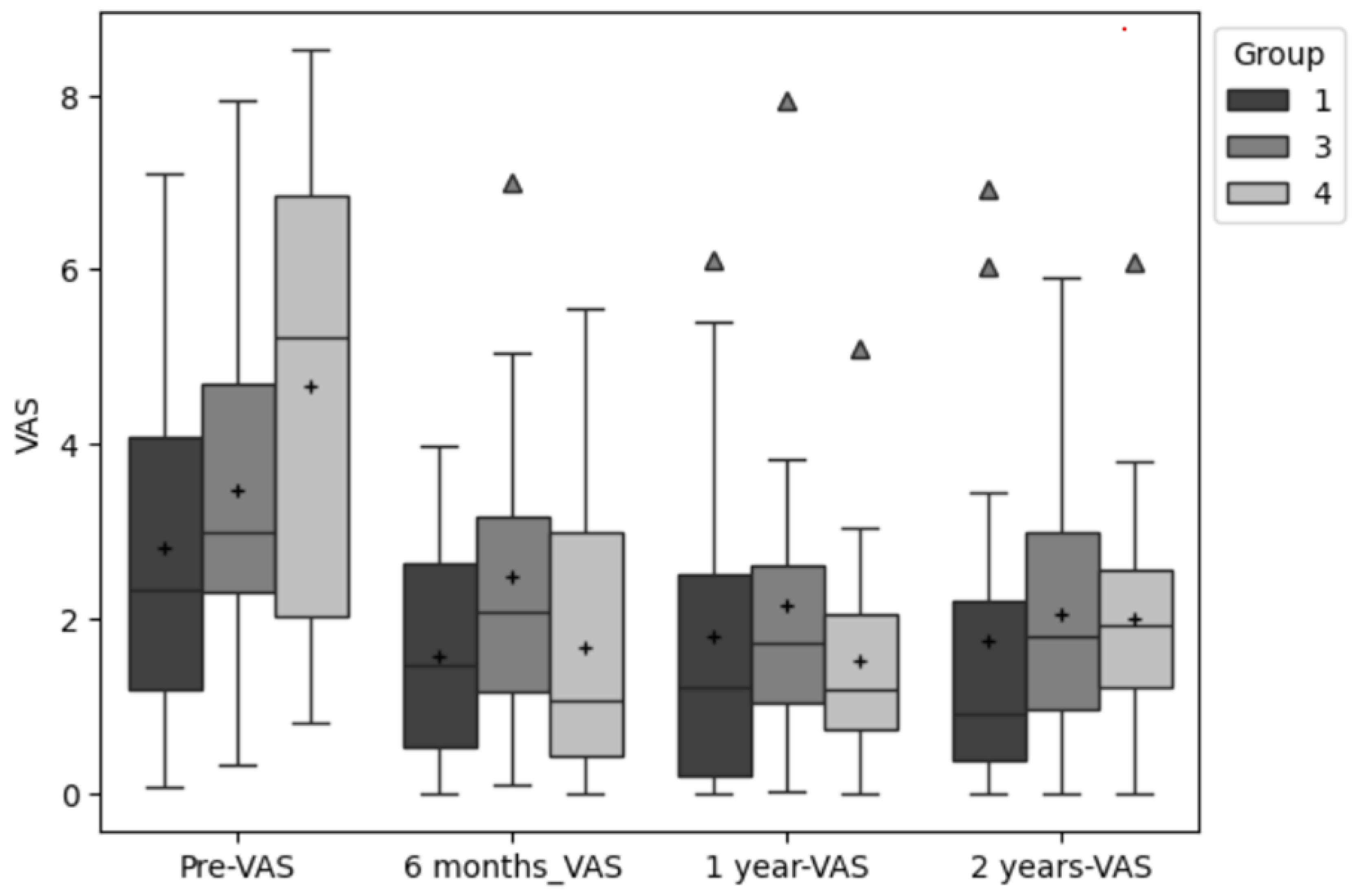

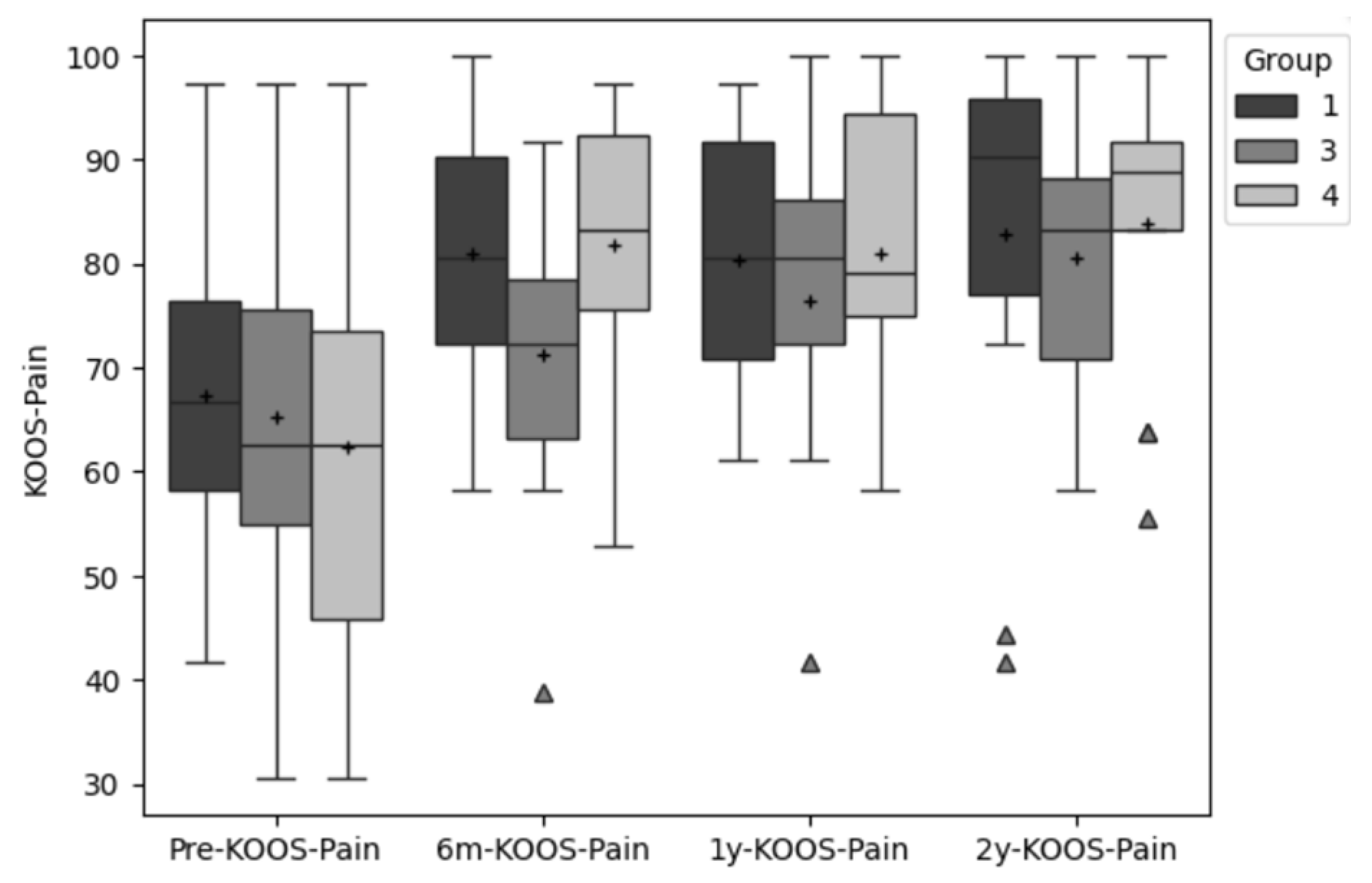

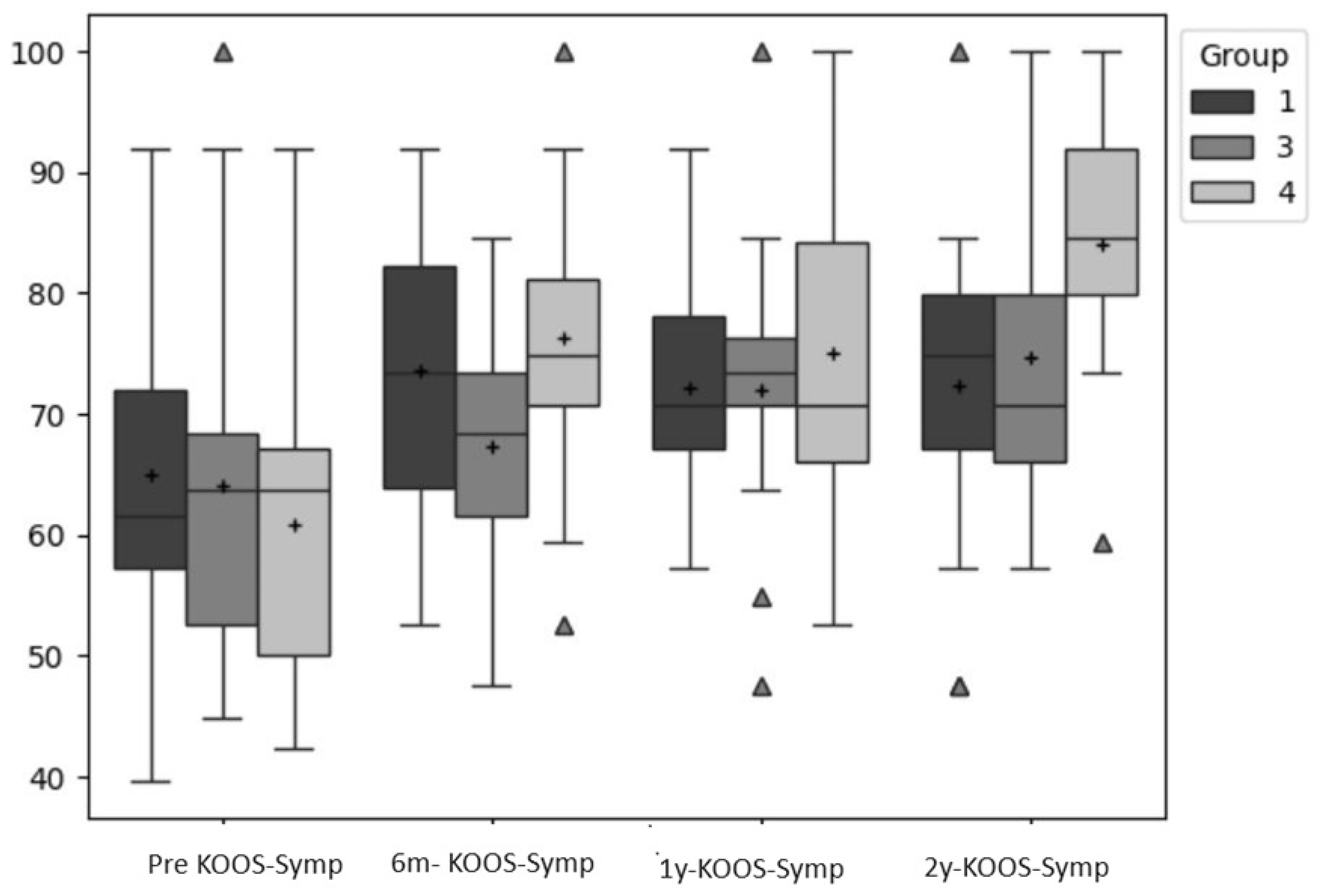

Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics for the VAS, the KOOS-Pain, and KOOS-Symptoms.

From pre surgery to six-month post, the VAS scores in all groups decreased. In MIC the decrement was 2.9, in AMIC 1.2 and in MACI 1.0 points. From six-month post to one year, all scores except for the AMIC group (+0.2) further decreased by 0.2 points (MIC) and 0.3 (MACI). From pre surgery to the latest follow up, all three groups decreased their VAS scores by 1.1 (AMIC), 2.4 (MACI), and 2.6 (MIC) respectively.

The Pain Subscale of the KOOS increased by 13.5, 5.9, and 19.5 points respectively for the AMIC, MACI and MIC groups from pre to post surgery. Overall, two years after surgery, the scores of the KOOS pain subscale raised by 13.3 points in the AMIC, 15.3 in the MACI, and by 21.6 points in the MIC compared to pre surgery.

The KOOS-Symptoms score raised by 8.64, 3.25, and 15.41 points for the AMIC, MACI, and MIC group respectively from pre- to 6 month post-surgery. The maximum score was reached 6 month post-surgery in the AMIC group (73.5), two years post-surgery in the MACI group (74.6) and two years post-surgery in the MIC group (83.97).

The ANOVA revealed no significant difference between all three groups for the primary outcomes VAS, KOOS-Pain and KOOS-Symptoms and no interaction between time and group. However, significant differences were found for the factor time in both pain related PROMs: VAS (p < .000; ES: ⴄ²=.27) and KOOS-Pain (p < .000; ES: ⴄ²=.30).

Post-hoc tests showed that for the VAS the differences between the first time point (pre surgery) and all other three time points were significant at the .05 level (p <=.001; p>.000; p<=.003). The same was evident for the KOOS-pain (p <=.003; p=.000; p=.000).

For the KOOS-Symptoms Score, the Factor time was also significant (p=.000; ES: ⴄ²=.26). Post-hoc tests revealed that the differences were significant only for the pre-test compared to any other timepoint (p <=.008; p=.001; p=.000).

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show boxplots for all groups and time points in comparison for the primary outcomes (VAS, KOOS-Pain, KOOS-Symptoms).

3.4. Patient-Reported Outcome Measurements on Function and Activity

Descriptive data of the secondary outcomes is displayed in

Table 4. The KOOS-ADL score improved by 8.37 points in the AMIC group, 14.34 in the group treated with MACI, and 17.50 in the MIC group from pre surgery to the two years follow up. Two groups gained the highest improvements from pre to six months post-surgery (AMIC: 4.87; MIC: 8.97). The MACI group gained the highest improvement from 6 months to 12 months post-surgery (10.2 points).

The QOL subscale showed the highest between-group differences at baseline. The AMIC group improved by 13.94 points (from 42.31 to 56.25) from pre surgery to the two year follow up. The MACI group improved by 22.92 points (from 26.56 to 49.48), and the MIC group by 31.77 (from 29.48 to 61.25).

The TAS was answered by 33 of the 48 included patients at all four time points (AMIC: n = 13; MACI: n = 8; MIC: n = 12). Scores were between 4.25 (MACI) and 4.29 (MIC) pre surgery and between 3.63 (MACI) and 3.71 (AMIC) in the two year follow up. All scores decreased from pre to six months after surgery (AMIC: -0.87; MACI: -1,92; MIC: -1.1) and approximated the pre-surgery score after two years.

For KOOS-ADL, the ANOVA revealed a highly significant effect of the within subject factor time point (p > .000; ES: ⴄ² = .20). Post hoc tests revealed that the changes between pre surgery and one year after surgery (p = .02) and two years after surgery (p < .000) reached significance.

The factor time also had a significant effect on the outcomes of the KOOS-QOL (p > .000; ES: ⴄ² = .30), with all three follow up time points being significantly different from pre surgery scores respectively (6m: p = .001; 1y: p > .000; 2y: p < .000).

The factor group had no significant effect on both outcomes (KOOS-ADL and KOOS-QOL).

The Friedmann tests did not reveal significant differences between time points. Conducted a one test for the total sample N = 33 differences in the time points reached significance (p < .05).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to retrospectively compare three procedures that are used for the treatment of cartilage defects in the knee joint. In chronological order, Matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation (MACI), Autologous Matrix-Induced Chondrogenesis (AMIC), and the Minced Cartilage Technique (MIC) as the most recently developed procedure were compared in terms of their patient-reported outcomes up to two years after treatment.

All three procedures have shown comparable outcomes in previous studies. However, a direct comparison of all three methods has not yet been carried out. For this reason, a matched-pair analysis was conducted to allow for comparability. The patients were matched for gender, age, BMI and, when possible, the location and size of the lesion.

As the most important finding of this study, most of the scores improved within the two years independently of treatment. Covering the cartilage defects resulted in a significant reduction in pain and symptoms for all three treatment groups. The patient reported pain outcomes already significantly improved within the first six month after surgery. In the three groups, the pain level remained relatively constant thereafter. This is consistent with existing publications. Kaiser et al. [

23] showed durable results for the AMIC procedure up to over 9 years and Gille et al.24 for the MACI procedure up to 15 years.

There are currently no comparable results available for the Minced Cartilage Implantation procedure with arthroscopic technique. For the open procedure, Massen25 and colleagues also found a significant reduction in pain as indicated by the Numeric Analog Scale (NAS) after two years. Runer et al. [

17] published 5-year results for the open procedure and found a reduction in pain indicated by the VAS score improving by 5 points after five years compared to before surgery. The reported results on pain of both studies are consistent with our findings.

In this study, the VAS score was improved by 2.6 points after two years which is close to the minimal clinically important difference MCID of 2.7 [

22]. Notably, the MCID was reached at one year post surgery. The VAS also improved in the other two groups, but their improvements were smaller than in the MIC group. One reason for this may be that the MIC group started from the worst baseline (pre) VAS score and thus had more potential to improve. This would be further to investigate.

For KOOS-Pain, two groups (AMIC and MIC) exceeded the PASS value of 71.5 [

21]. For the MACI group, this was the case after one year. This corresponds to the time point when the clinically important difference (CID) of 8.3 points from baseline was reached in all three groups. Comparing the development of the KOOS-Pain scores respectively, the AMIC group did not further improve after six months, the MACI group improved constantly between all time points and the MIC group improved strongly at the beginning and continued to improve afterwards. Like the VAS score, the MIC treatment revealed the strongest improvement from pre- to two years after surgery but also started with the worst baseline.

Regarding pain, the VAS and KOOS-Pain show similar results in terms of the magnitude and progress of improvement. Both are pain measures, but KOOS pain is more specific to the retrospectively assessed situations, whereas the VAS is a more unspecific assessment of pain at the time of rating. Therefore, both should be highly correlated.

The symptoms-subscale of the KOOS is closely related to the pain-subscale as it also reflects the patients’ evaluation of the joints’ condition. Therefore, it can be expected that both scales would be highly correlated in terms of their development. In fact, our results revealed that the symptoms scores had a similar development compared to the pain scores. The AMIC group nearly reached a plateau after the 6 month timepoint, the MACI group revealed a constant improvement and last, the MIC group had the largest improvement from pre- to six month post-surgery and thereafter further improvements. Like the results for pain, the MIC group gained the largest increase in the symptoms score compared to the other two groups from pre- to two years after surgery. The PASS of 71.5 [

22] was reached after 6 month in the AMIC and MIC group and after one year in the MACI group. The CID (10.7) was exceeded by far in the MIC group from pre surgery tot wo years post. In the other two groups it was slightly missed. This may also be explained by the difference in baseline values.

Considering the improvement in pain and symptoms, it is not surprising that joint function in everyday situations, as represented by the KOOS-ADL score, also significantly improved after surgery. The KOOS-ADL also asks specific questions about the extent to which a person feels restricted by their affected joint when performing daily activities. Here, the improvement was highest for the MIC group again, followed by MACI and then AMIC. The CID of 8.8 was exceeded in MACI (after one year) and MIC (after six month) but slightly missed (< 0.5 points) in the AMIC group. The PASS of 86.8 was reached only in the MIC group and nearly reached in the other two groups. Again, it is important to consider the differences in the baseline scores when comparing the improvements between the three groups. Overall, each of the treatments resulted in significant improvements in daily functioning of the knee joint. A tendency towards faster recovery of function can be noted after MIC treatment.

Pain and limited joint function severely affect overall quality of life (QOL) in an individual. Cartilage repair, like almost every medical treatment, aims at improving quality of life for the patient. The KOOS-QOL therefore was also assessed. All three groups were severely affected in QOL by their joints before the surgery as indicated by the sores below 50 points. Patients in all three groups exceeded the PASS of 50.0 points or nearly reached it. The CID of 18.8 was reached by the MACI group (after 2 years) and the MIC group (after one year) but slightly missed by the AMIC group. The AMIC group however started from a baseline of 42.31 far higher than the other two groups (MACI: 26.56; MIC: 29.48). Since KOOS sub-scores are highly correlated 26, the magnitude of baseline difference for the QOL subscale was as surprising as the fact that this time the AMIC group was the outlier.

Last, we aimed at evaluating how activity levels changed trough the different treatments. Here, we evaluated the TAS-Score which presents different activity levels to choose from as a patient. As evident from the statistical analysis, we could not show significant differences between all four time points. Furthermore, the score more likely decreased from baseline. This measure represents a ranking from 0 – 10 with each number representing a certain state of activity. Considering this fact, scores must be seen as activity stages. The activity state therefore recovered to baseline level (stage 4) after one year in AMIC and MIC and after two years in MACI. Comparably, Gille et al. [

24] found the Tegner score improving from 3.0 to 3.6 after five years and further to 5.2 after 5 years, which indicates that the activity level may further improve in our participants.

Overall, our results are comparable with previous studies in terms of improvements in pain and function after surgery.

4.1. Limitations

This study was the first to directly compare three different competing procedures to deduct treatment recommendations for clinical practice. It must however be admitted that there is some limitation of the predictive value caused by the difference in baseline values and the retrospective design of the study. Furthermore, female participants are underrepresented in this study. Despite intensive efforts in the matching process, the location and size of the lesion are not 100% equally distributed, and the previous treatment was not considered in advance. The last limitation that must be discussed is the lack of outcome measures other than the patient reported outcomes. The addition of more objective data, such as clinical mobility or strength measurements and imaging data (MRI), would contribute to a better understanding of the differences between the three methods. For future studies, a prospective approach that includes female and male participants equally and considers the baseline values of the main outcomes as well as prior treatment would be highly recommended.

5. Conclusions

This study shows that all three procedures (AMIC, MACI, MIC) are equally recommendable for the treatment of cartilage lesions in the knee joint. The appropriate procedure can therefore be chosen according to the resources, skills and preferences of the surgeon and the clinic. MIC may provide an advantage in recovery time, but all three procedures will likely lead to comparable improvements of pain, function and quality of live for the patient.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, St.S. and J.H.; methodology, D.L.; software, D.L. & RO; validation, St.S.., A.I. and J.H..; formal analysis, G.S. and R.O; investigation, St.S., A.I. and J.H..; resources, J.H..; data curation, D.L..; writing—original draft preparation, St.S. and D.L..; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, D.L..; supervision, G.S. & J.H.; project administration, St.S., D.L., and J.H..; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

No external funding was received for this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Ärztekammer Hamburg (2021-10018-Boff 13.Dec. 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” Authors must identify and declare any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results. Any role of the funders in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results must be declared in this section. If there is no role, please state “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMIC |

Autologous matrix-induced Chondrogenesis |

| KOOS |

Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score |

| MACI |

Matrix-Induced Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation |

| MIC |

Arthroscopic Minced Cartilage |

| TAS |

Tegner Activity Scale |

| VAS |

Visual Analogue Scale |

References

- Wenzl, M.E. [No title found]. Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger. 2006, 188, 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomoll, A.H.; Minas, T. The quality of healing: Articular cartilage. Wound Repair Regeneration. 2014, 22, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.S.; Frenkel, S.R.; Di Cesare, P.E. Repair of articular cartilage defects: Part, I. Basic Science of cartilage healing. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 1999, 28, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.D.; Frank, R.M.; McCormick, F.M.; Cole, B.J. Minced Cartilage Techniques. Operative Techniques in Orthopaedics. 2014, 24, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, H.; Connock, M.; Pink, J.; et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation in the knee: Systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2017, 21, 1–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzmann, G.M.; Calek, A.K.; Preiss, S. Second-Generation Autologous Minced Cartilage Repair Technique. Arthroscopy Techniques. 2017, 6, e127–e131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, S.Z.; Bentley, G.; Briggs, T.W.R.; et al. Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation in the Knee: Mid-Term to Long-Term Results. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2014, 96, 824–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; Ossendorff, R.; Holz, J.; Salzmann, G.M. Arthroscopic Minced Cartilage Implantation (MCI): A Technical Note. Arthroscopy Techniques. 2021, 10, e97–e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gille, J.; Meisner, U.; Ehlers, E.M.; Müller, A.; Russlies, M.; Behrens, P. Migration pattern, morphology and viability of cells suspended in or sealed with fibrin glue: A histomorphologic study. Tissue and Cell. 2005, 37, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gille, J.; Ehlers, E.M.; Okroi, M.; Russlies, M.; Behrens, P. Apoptotic chondrocyte death in cell-matrix biocomposites used in autologous chondrocyte transplantation. Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger. 2002, 184, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kon, E.; Filardo, G.; Di Martino, A.; Marcacci, M. ACI and MACI. J Knee Surg. 2012, 25, 017–022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedi, A.; Feeley, B.T.; Williams, R.J. Management of Articular Cartilage Defects of the Knee. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-American Volume. 2010, 92, 994–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vega, P.L.O.; Bauxauli, V.C.; Corella, F.; Andrade, C.M. AMIC Technique for the Treatment of Chondral Injuries of the Hand and Wrist. Revista Iberoamericana de Cirugía de la Mano. 2021, 49, e165–e175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, F.; Roessner, A.; Zimmermann, E. Closure of osteochondral lesions using chondral fragments and fibrin adhesive. Arch Orth Traum Surg. 1983, 101, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, F.; Yanke, A.; Provencher, M.T.; Cole, B.J. Minced Articular Cartilage—Basic Science, Surgical Technique, and Clinical Application. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review. 2008, 16, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Grad, S.; Stoddart, M.J.; et al. Particulate cartilage under bioreactor-induced compression and shear. International Orthopaedics (SICOT). 2014, 38, 1105–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runer, A.; Ossendorff, R.; Öttl, F.; et al. Autologous minced cartilage repair for chondral and osteochondral lesions of the knee joint demonstrates good postoperative outcomes and low reoperation rates at minimum five-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023, 31, 4977–4987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oprenyeszk, F.; Sanchez, C.; Dubuc, J.E.; et al. Chitosan Enriched Three-Dimensional Matrix Reduces Inflammatory and Catabolic Mediators Production by Human Chondrocytes. PLoS ONE. 2015, 10, e0128362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, E.L.H.; Coleman, R.M.; Stegemann, J.P. Biomimetic microbeads containing a chondroitin sulfate/chitosan polyelectrolyte complex for cell-based cartilage therapy. J Mater Chem, B. 2015, 3, 7920–7929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzzarelli, R.A.A.; El Mehtedi, M.; Bottegoni, C.; Gigante, A. Physical properties imparted by genipin to chitosan for tissue regeneration with human stem cells: A review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2016, 93, 1366–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, J.; Lansdown, D.A.; Davey, A.; Davis, A.M.; Cole, B.J. The clinically important difference and patient acceptable symptomatic state for commonly used patient-reported outcomes after knee cartilage repair. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 2021, 49, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, K.; Kelley, B.V.; Arshi, A.; McAllister, D.R.; Fabricant, P.D. Comparative effectiveness of cartilage repair with respect to the minimal clinically important difference. The American journal of sports medicine, 2019, 47, 3284–3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, N.; Jakob, R.P.; Pagenstert, G.; Tannast, M.; Petek, D. Stable clinical long term results after AMIC in the aligned knee. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2021, 141, 1845–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gille, J.; Behrens, P.; Schulz, A.P.; Oheim, R.; Kienast, B. Matrix-Associated Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation: A Clinical Follow-Up at 15 Years. CARTILAGE 2016, 7, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massen, F.K.; Inauen, C.; Harder, L.P.; Runer, A.; Preiss, S.; Salzmann, G.M. One-step autologous minced cartilage procedure for the treatment of knee joint chondral and osteochondral lesions: A series of 27 patients with 2-year follow-up. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine 2019, 7, 2325967119853773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, N.J.; Prinsen, C.A.C.; Christensen, R.; Bartels, E.M.; Terwee, C.B.; Roos, E.M. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): Systematic review and meta-analysis of measurement properties. Osteoarthritis and cartilage 2016, 24, 1317–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).