Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design for In Vivo Experiments

Tissue Collection and Processing

Histopathological Evaluation

Hyperspectral Dark-Field Microscopy

Biochemical and Immunological Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Macroscopic Findings

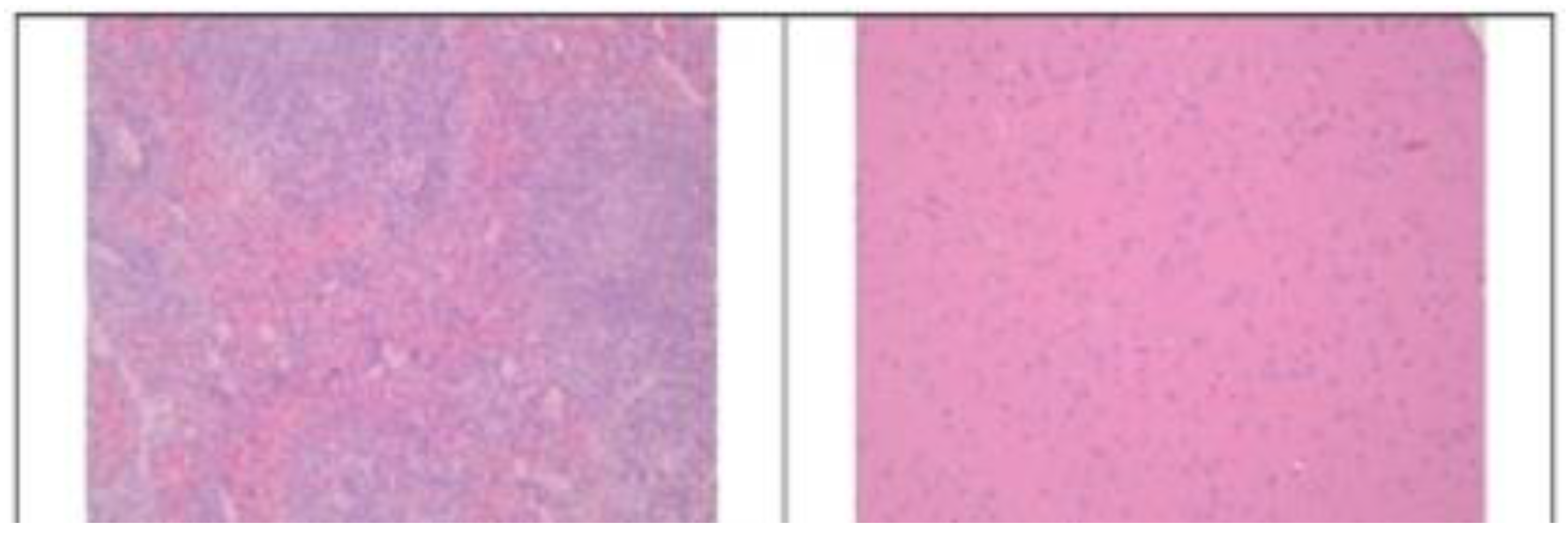

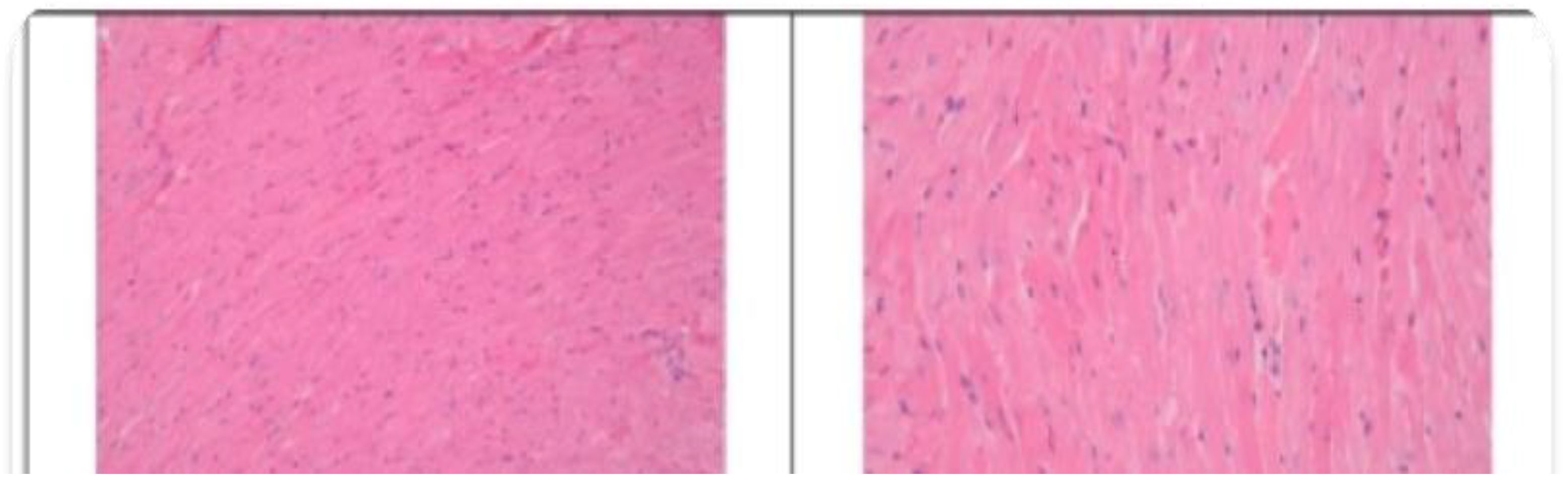

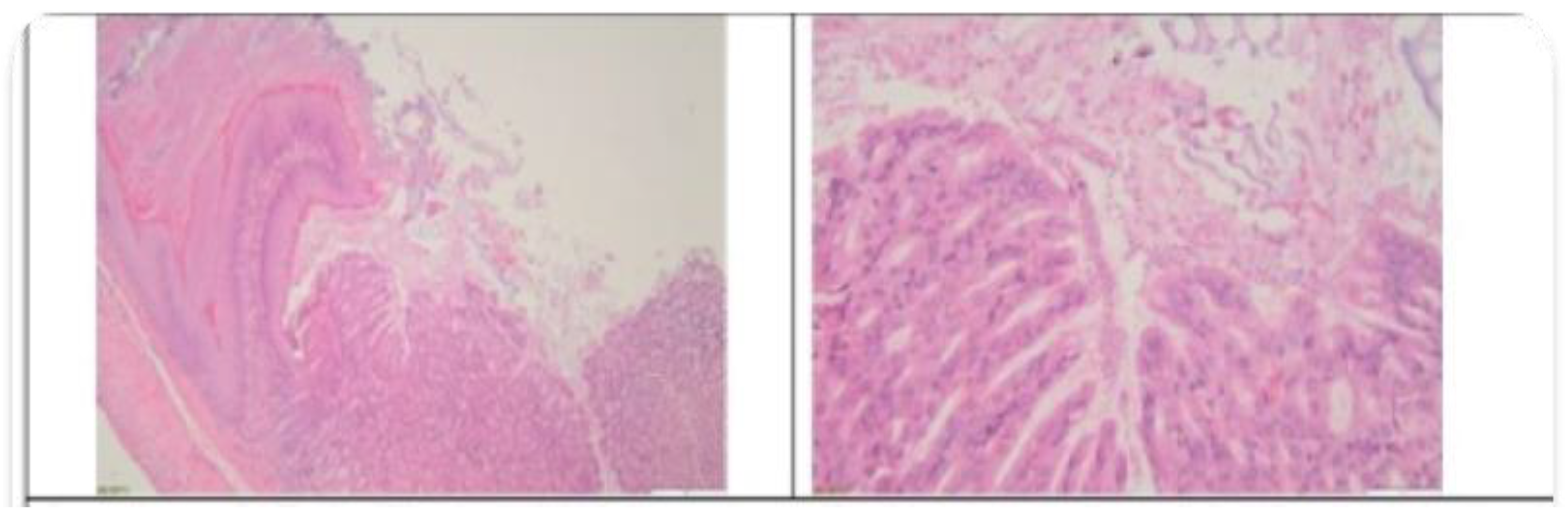

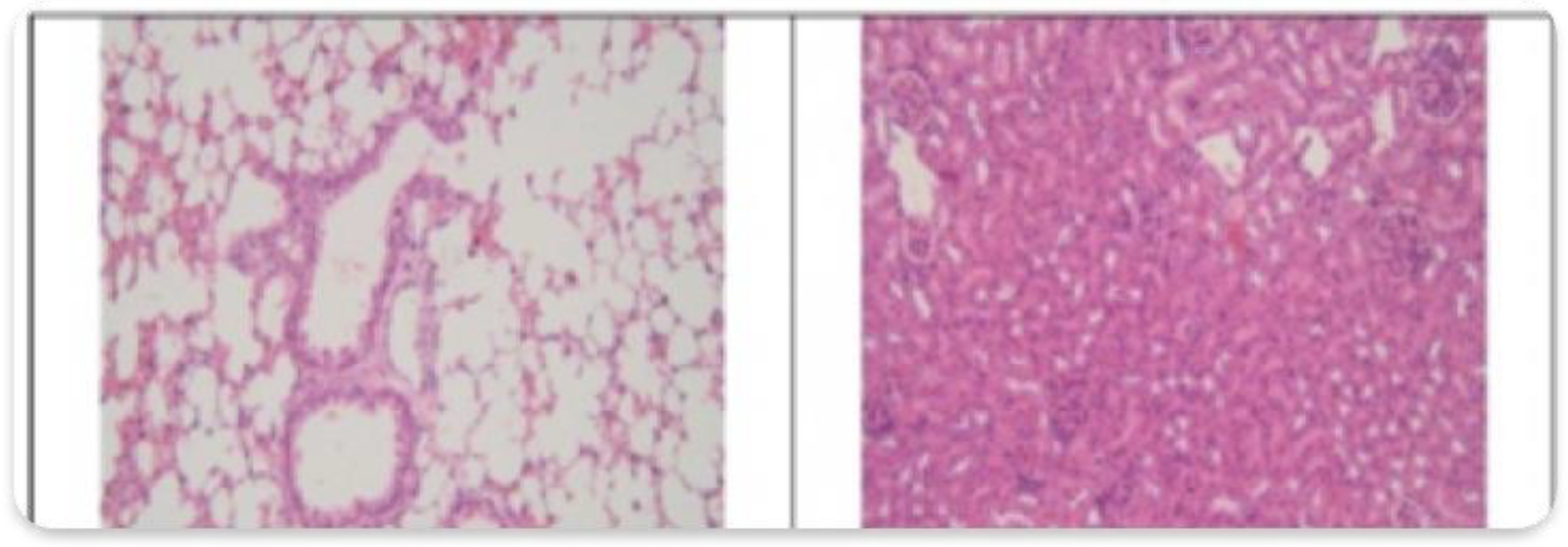

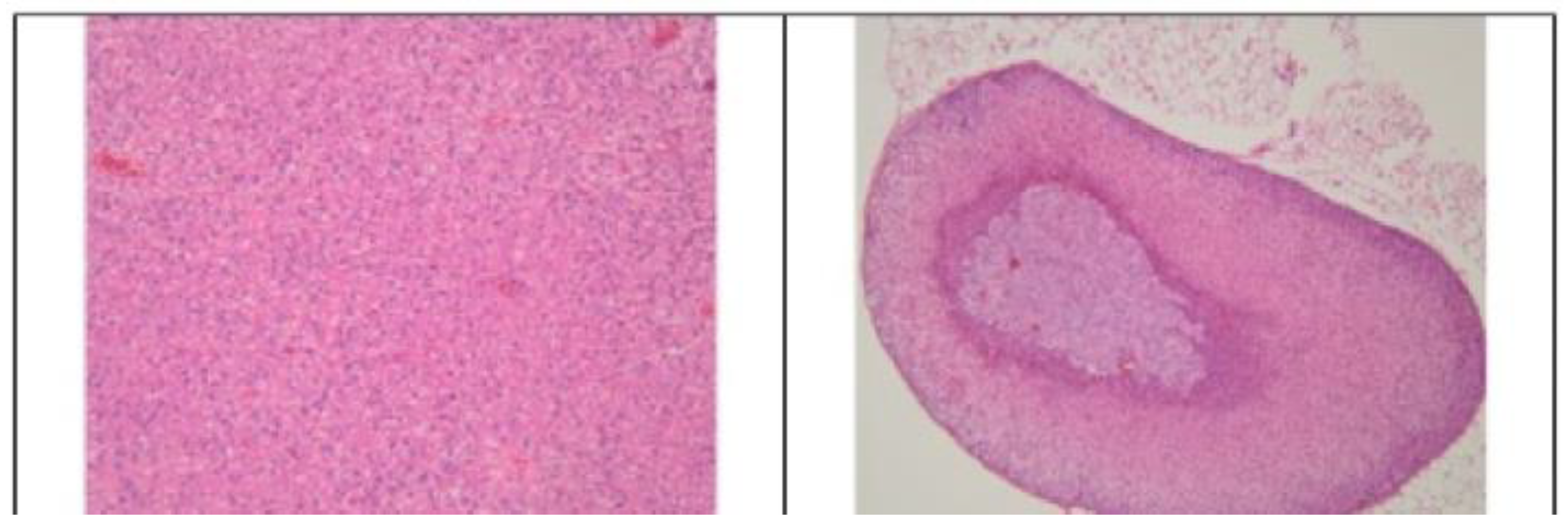

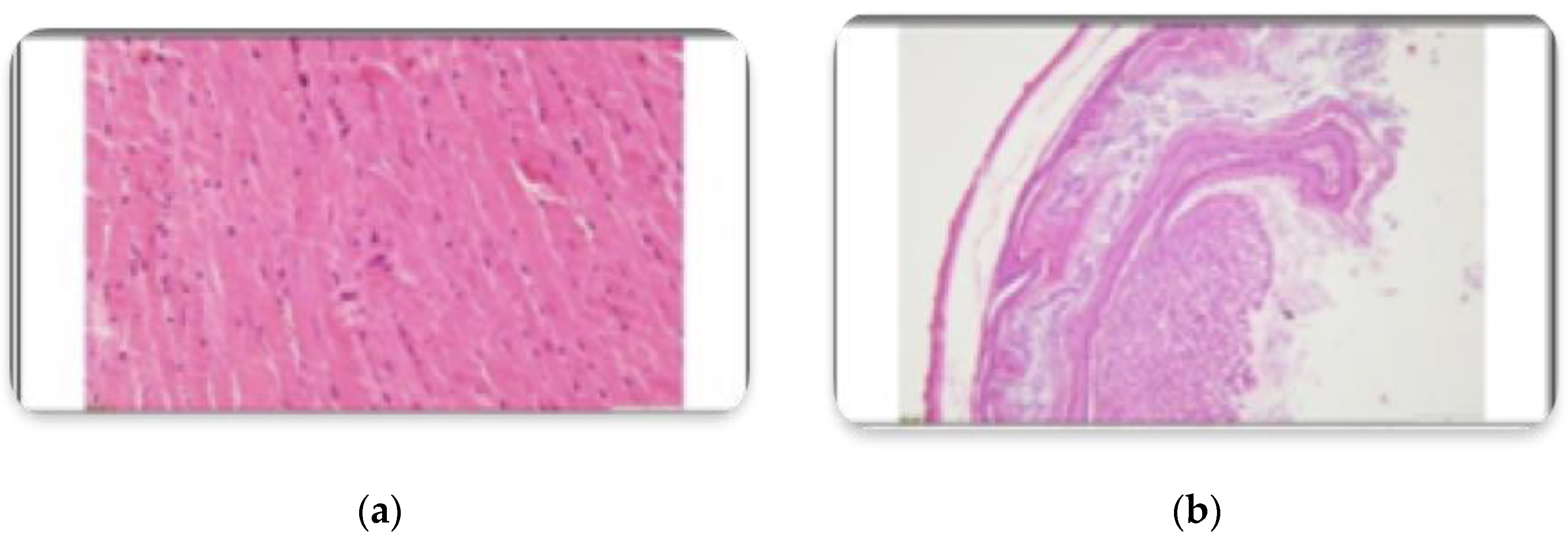

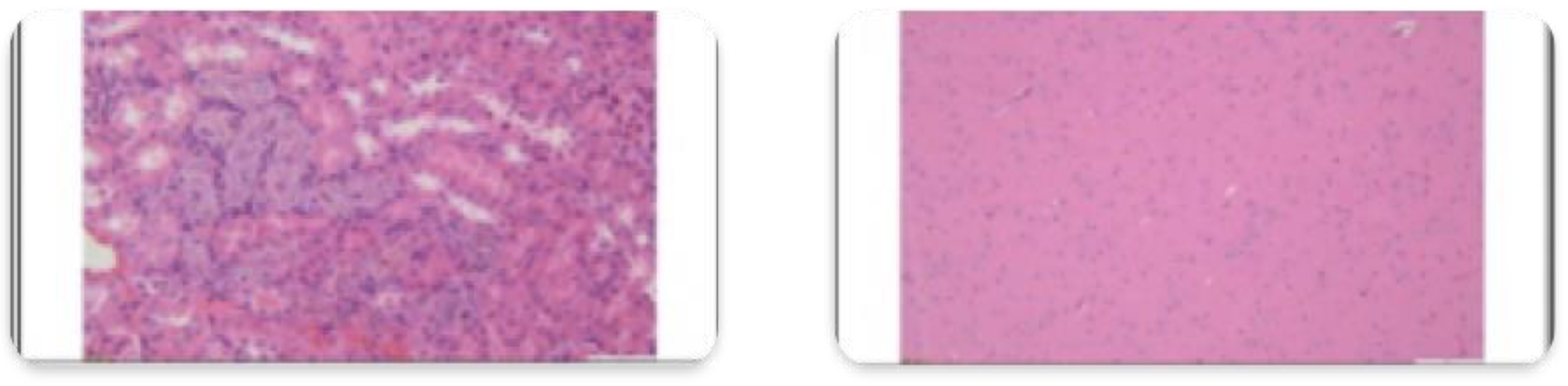

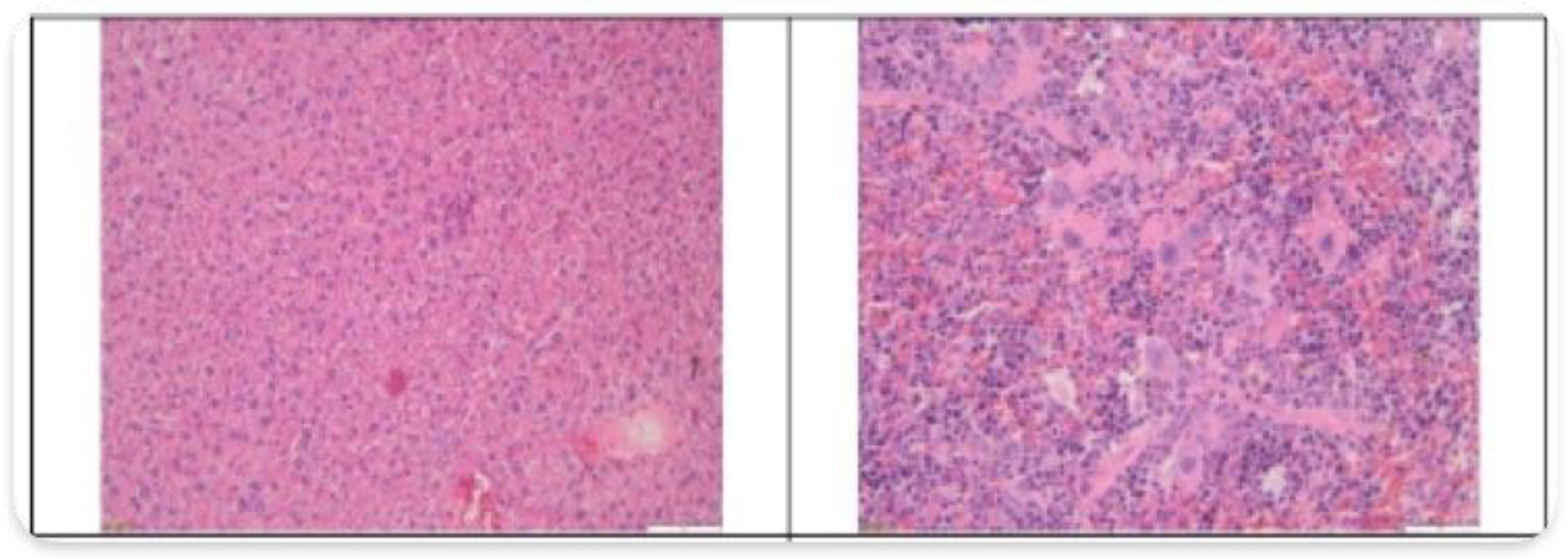

3.2. Histopathological Findings

3.3. Hyperspectral Dark-Field Microscopy

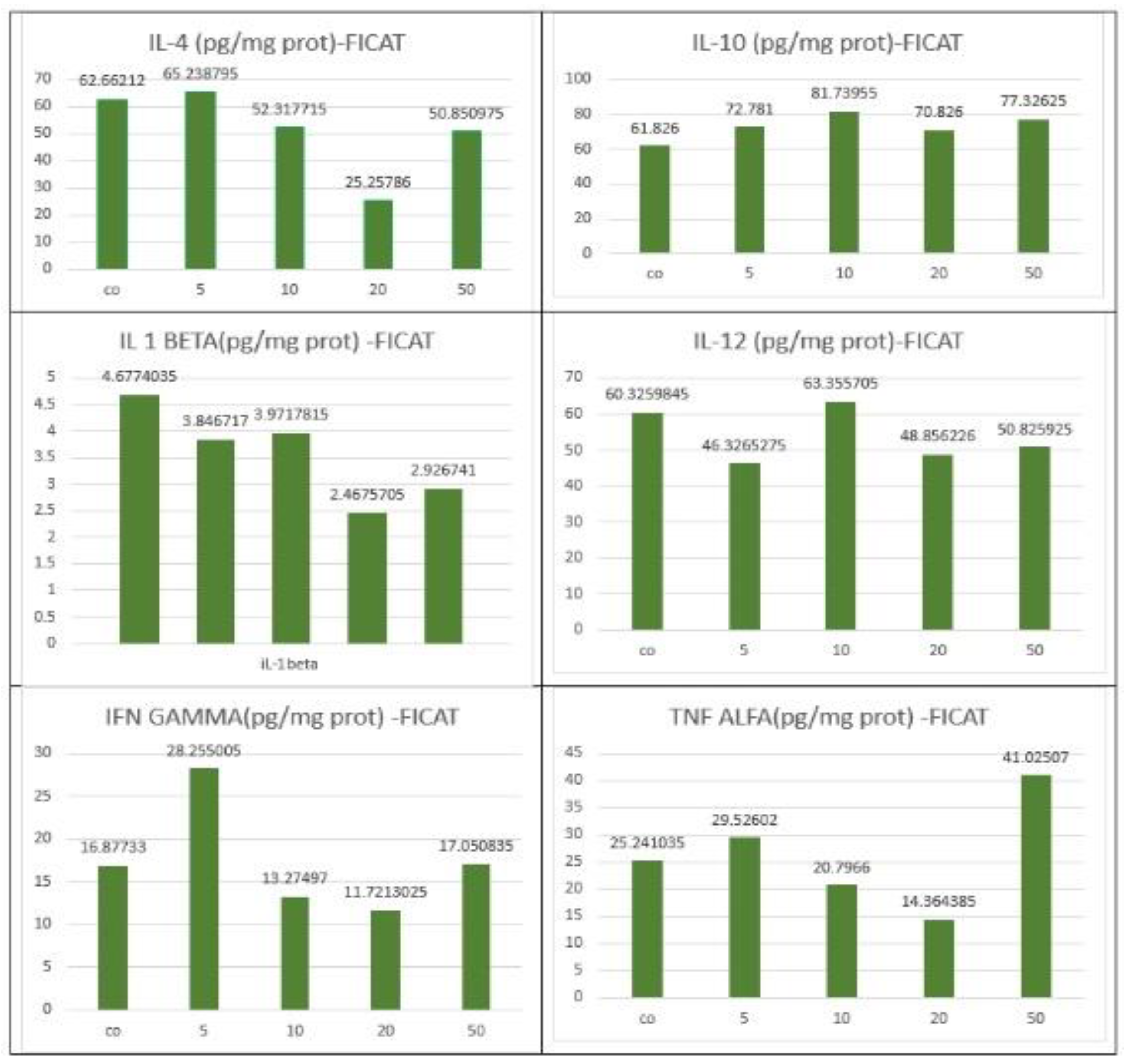

3.4. Biochemical and Immunological Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AuNP | Gold nanoparticle |

| CEA | Carcinoembrionic Antigen |

| CEA-AuNP | CEA functionalized gold nanoparticles |

| HE | Hematoxilin & Eozine |

References

- Granados-Romero JJ, Valderrama-Treviño AI, Contreras-Flores EH, Barrera-Mera B, Herrera Enríquez M, Uriarte-Ruíz K, et al. Colorectal cancer: a review. Int J Res Med Sci. 2017;5(11):4667. [CrossRef]

- Stintzing S. Management of colorectal cancer. F1000prime reports. 2014;6:108. [CrossRef]

- Mármol I, Sánchez-de-Diego C, Pradilla Dieste A, Cerrada E, Rodriguez Yoldi MJ. Colorectal carcinoma: a general overview and future perspectives in colorectal cancer. International journal of molecular sciences. 2017;18(1):197. [CrossRef]

- Fan T, Zhang M, Yang J, Zhu Z, Cao W, Dong C. Therapeutic cancer vaccines: advancements, challenges and prospects. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2023;8(1):450. [CrossRef]

- Bhagat A, Lyerly HK, Morse MA, Hartman ZC. CEA vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023;19(3):2291857.

- Hammarström S, editor The carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) family: structures, suggested functions and expression in normal and malignant tissues. Seminars in cancer biology; 1999: Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek M, Poznańska J, Fechner F, Michalska N, Paszkowska S, Napierała A, et al. Cancer Vaccine Therapeutics: Limitations and Effectiveness-A Literature Review. Cells. 2023;12(17). [CrossRef]

- Almeida JP, Figueroa ER, Drezek RA. Gold nanoparticle mediated cancer immunotherapy. Nanomedicine. 2014;10(3):503–14. [CrossRef]

- Ferrando RM, Lay L, Polito L. Gold nanoparticle-based platforms for vaccine development. Drug Discovery Today: Technologies. 2020;38:57–67. [CrossRef]

- Dykman L, Khlebtsov N. Gold nanoparticles in biomedical applications: recent advances and perspectives. Chemical Society Reviews. 2012;41(6):2256–82. [CrossRef]

- Prophet EB. Laboratory methods in histotechnology: American Registry of Pathology; 1992.

- Ren H, Jia W, Xie Y, Yu M, Chen Y. Adjuvant physiochemistry and advanced nanotechnology for vaccine development. Chemical Society Reviews. 2023;52(15):5172–254. [CrossRef]

- Zaccariotto GdC, Bistaffa MJ, Zapata AMM, Rodero C, Coelho F, Quitiba JoVBo, et al. Cancer Nanovaccines: Mechanisms, Design Principles, and Clinical Translation. ACS Nano. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Huang R, Zhu X, Wang L, Wu C. Synthesis, properties, and optical applications of noble metal nanoparticle-biomolecule conjugates. Chinese Science Bulletin. 2012;57:238–46. [CrossRef]

- Rai M, Ingle AP, Gupta I, Brandelli A. Bioactivity of noble metal nanoparticles decorated with biopolymers and their application in drug delivery. International journal of pharmaceutics. 2015;496(2):159–72. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Q, Pi J, Woods CG, Jarabek AM, Clewell III HJ, Andersen ME. Hormesis and adaptive cellular control systems. Dose-Response. 2008;6(2):dose–response. 07–028. Zhang.

- Zhang Q, Bhattacharya S, Pi J, Clewell RA, Carmichael PL, Andersen ME. Adaptive posttranslational control in cellular stress response pathways and its relationship to toxicity testing and safety assessment. Toxicological Sciences. 2015;147(2):302–16. [CrossRef]

- Byrne HJ, Maher MA. Numerically modelling time and dose dependent cytotoxicity. Computational Toxicology. 2019;12:100090. [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek M, Abualrous ET, Sticht J, Álvaro-Benito M, Stolzenberg S, Noé F, et al. Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and MHC class II proteins: conformational plasticity in antigen presentation. Frontiers in immunology. 2017;8:292. [CrossRef]

- Roy AA, Pokale R, Mukharya A, Jadhav SR, Naik GARR, Rachana S, et al. Innovative Organic Core–Nonmagnetic Shell Nanoconstructs: Pioneering Precision in Cancer Theranostics. Core-Shell Nano Constructs for Cancer Theragnostic: Current Scenario, Challenges and Regulatory Aspects: Springer; 2025. p. 415–49.

- Ge F, Yao J, Fu X, Guo Z, Yan J, Zhang B, et al. Amyloidosis in transgenic mice expressing murine amyloidogenic apolipoprotein A-II (Apoa2c). Lab Invest. 2007;87(7):633–43. [CrossRef]

- Kakinen A, Javed I, Davis TP, Ke PC. In vitro and in vivo models for anti-amyloidosis nanomedicines. Nanoscale Horizons. 2021;6(2):95–119. [CrossRef]

- Cenariu D, Iluta S, Zimta A-A, Petrushev B, Qian L, Dirzu N, et al. Extramedullary Hematopoiesis of the Liver and Spleen. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021;10(24):5831. [CrossRef]

- Kim, CH. Homeostatic and pathogenic extramedullary hematopoiesis. Journal of blood medicine. 2010:13–9. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto K, Miwa Y, Abe-Suzuki S, Abe S, Kirimura S, Onishi I, et al. Extramedullary hematopoiesis: Elucidating the function of the hematopoietic stem cell niche. Molecular medicine reports. 2016;13(1):587–91. [CrossRef]

- Li S-D, Huang L. Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of nanoparticles. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2008;5(4):496–504. [CrossRef]

- Li S-D, Huang L. Nanoparticles evading the reticuloendothelial system: role of the supported bilayer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes. 2009;1788(10):2259–66. [CrossRef]

- Saraiva M, O’garra A. The regulation of IL-10 production by immune cells. Nature reviews immunology. 2010;10(3):170–81. [CrossRef]

- Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nature reviews immunology. 2008;8(12):958–69. [CrossRef]

- Ma X. TNF-α and IL-12: a balancing act in macrophage functioning. Microbes and Infection. 2001;3(2):121–9. [CrossRef]

- He J-s, Liu S-j, Zhang Y-r, Chu X-d, Lin Z-b, Zhao Z, et al. The application of and strategy for gold nanoparticles in cancer immunotherapy. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2021;12:687399. [CrossRef]

- Sani A, Cao C, Cui D. Toxicity of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs): A review. Biochemistry and biophysics reports. 2021;26:100991. [CrossRef]

- Finn, OJ. Cancer immunology. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(25):2704–15. [CrossRef]

- Chen DS, Mellman I. Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer–immune set point. Nature. 2017;541(7637):321–30. [CrossRef]

- Thomas EM, Wright JA, Blake SJ, Page AJ, Worthley DL, Woods SL. Advancing translational research for colorectal immuno-oncology. British Journal of Cancer. 2023;129(9):1442–50. [CrossRef]

- Gambinossi F, Mylon SE, Ferri JK. Aggregation kinetics and colloidal stability of functionalized nanoparticles. Advances in colloid and interface science. 2015;222:332–49. [CrossRef]

- Shafiee MAM, Asri MAM, Alwi SSS. Review on the In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assessment in Accordance to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Malaysian Journal of Medicine & Health Sciences. 2021;17(2).

- Wang Y, Pi C, Feng X, Hou Y, Zhao L, Wei Y. The influence of nanoparticle properties on oral bioavailability of drugs. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 2020:6295–310. [CrossRef]

- den Haan JM, Arens R, van Zelm MC. The activation of the adaptive immune system: cross-talk between antigen-presenting cells, T cells and B cells. Immunology letters. 2014;162(2):103–12. [CrossRef]

| Group | Treatment | Dose |

| Group 1, n=6 | CEA-AuNPs in PBS | 50 mg/kg |

| Group 2, n=6 | CEA-AuNPs in PBS | 20 mg/kg |

| Group 3, n=6 | CEA-AuNPs in PBS | 10 mg/kg |

| Group 4, n=6 | CEA-AuNPs in PBS | 5 mg/kg |

| Control Group, n=6 | PBS (vehicle control) | 0 mg/kg |

| Organ | Cytokine | Observed Change | Dose Dependency | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spleen | IL-10 | Increased significantly vs IL-12 | Dose-dependent | Anti-inflammatory activation (M2-like) |

| Spleen | IL-12 | Mild increase | Present but less pronounced | Balanced Th1 response |

| Liver | IL-10 | Increased | Moderate at higher doses | Partial anti-inflammatory response |

| Liver | IL-12 | Increased | Parallel to IL-10 | Mixed immune activation |

| Liver | TNF-α | Sporadic increase | Most evident at 50 mg/kg | Early signs of hepatic immune stress |

| Liver | IL-1β | Sporadic increase | Not consistent at lower doses | Localized inflammatory activation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).