Introduction

Despite advances in understanding of lung cancer's risk, progression, immunologic regulation, and accessible therapies, lung cancer continues to be the leading cause of cancer-related fatalities [

1]. Cancer is a disease that develops when certain body cells multiply uncontrollably and spread to other organs [

2]. Cancer is a disorder characterized by uncontrolled cell proliferation brought on by modified cells exposed to natural selection evolution [

3]. Smoking increases the risk of lung cancer by five to ten times with a clear dose-response relationship. Exposure to ambient tobacco smoke increases the risk of lung cancer in nonsmokers by 20% [

4].

Lung cancer risk has also been linked to host variables, such as infections, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and family history of lung cancer [

5]. Chromosome regions on 15q25, 6p21, and 5p15 have been consistently linked to lung cancer risk in studies to discover genes related with lung cancer susceptibility [

6]. Numerous genetic polymorphisms, including genes producing proteins linked to the activity to metabolize tobacco smoke carcinogens and to inhibit mutations generated by those carcinogens, were found after a thorough investigation into the genetic variables implicated in tobacco-related lung malignancies [

7].

In 2020, there were an anticipated 1.8 million lung cancer-related deaths and 2.2 million new cases of lung cancer [

8]. In Mexico, the age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) was 5.9 per 100,000, but in Denmark, it was 36.8 per 100,000 [

9]. Mexico's age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR) was 4.9 per 100,000, whereas Poland's was 32.8 per 100,000 [

10]. Men's ASIR and ASMR were almost twice as high as women's [

11].

In the United States of America (USA), the ASIR for lung cancer decreased between 2000 and 2012 and was higher in males [

12]. In China, both men and women's age-specific incidence rates of lung cancer for those aged 50 to 59 years exhibited an increasing trend [

13].

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) are the two forms of lung cancer [

14]. The majority of cancer-related fatalities worldwide are caused by non-small-cell lung cancer, one of the most common cancer kinds [

15].

Throughout the years, radiation, chemotherapy, and traditional surgery were used to treat NSCLC [

16]. The current study's goal was to use bioinformatics and molecular docking to create a new therapeutic lipid nanoparticle-mRNA vaccine that contains the mRNA of mutant p53 and overexpressed CEA to fight NSCLC. Additionally, the test vaccine's immunogenicity is screened in vitro via cell culturing testing.

Material and Methods

All chemical materials used used in the present study were purchased from Al-Nasr pharmaceutical chemical company in Qalyobia, Egypt. All chemical reagents used were of analytical grade.

Instruments used in the present study are displayed in

Table 1.

Between Jan 2025 and Jun 2025. This study was performed at Microbiology and Immunology Department of the Faculty of Pharmacy in Cairo University localized in Egypt country.

Screening experimental study.

The aim of this method was to collect and process fresh NSCLC tumor samples for in vitro testing of an mRNA vaccine encoding mutant p53 and overexpressed CEA. The purpose was to evaluate vaccine uptake, antigen expression, and immune responses using patient-derived tumor cells. The protocol comprised the following steps:

Patients diagnosed with NSCLC, preferably with adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma, were selected for sample collection. Tumors with known CEA overexpression and p53 mutations were prioritized. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board of the Faculty Pharmacy at Cairo University located in Egypt with number VKS358 in date 2-February-2025 , and informed consent was secured from all patients prior to sample collection.

Fresh tumor tissues (0.5–1.0 cm³) were collected in sterile tubes containing ice-cold RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin, and 1% Amphotericin B. Samples were transported on ice to the laboratory within 2 to 4 hours of resection or biopsy.

Tumor tissues were processed under a biosafety level 2 cabinet. Samples were rinsed three times with sterile PBS and minced into ~1 mm³ fragments using sterile scalpels. The tissue fragments were digested using Collagenase IV (1–2 mg/ml) and DNase I (50–100 µg/ml) at 37°C for 1 to 2 hours with gentle shaking. The digested mixture was filtered through a 70 µm strainer, centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 minutes, and the pellet was resuspended in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS and antibiotics. Cells were plated in collagen-coated flasks or low-adherence plates for culture.

Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO₂ incubator. Cell morphology and viability were monitored daily. Expressions of CEA and p53 were confirmed by ELISA. Flow cytometry was performed to identify epithelial markers such as EpCAM and cytokeratins.

Cells at passages 2 to 4 were used for vaccine testing. Cultured NSCLC cells were transfected with the mRNA-LNP vaccine encoding mutant p53 and CEA. Expression of vaccine-encoded antigens was assessed using ELISA and flow cytometry. Co-culture with dendritic cells was performed to evaluate antigen presentation, and cytokine levels such as IFN-γ and IL-6 were measured post-treatment. CTL killing assays were conducted using autologous or HLA-matched T cells.

All steps were documented, including patient ID (anonymized), tumor type, CEA/p53 status, culture passage, and vaccine exposure date. Cryopreservation of viable tumor cells was performed using freezing medium (90% FBS + 10% DMSO) and stored in liquid nitrogen.

All procedures were conducted with appropriate personal protective equipment. Human tissue waste was disposed of according to BSL-2 safety protocols, and sterility was maintained throughout the culture process.

Methods

Bioinformatics and Molecular docking studies of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine encoding overexpressed CEA and mutant p53:

Sequence Retrieval and Mutation Analysis:

The protein sequences of human TP53 (UniProt ID: P04637) and CEACAM5 (UniProt ID: P06731) were retrieved from the UniProt database. The TP53 hotspot mutation R248Q, commonly observed in NSCLC, was introduced using sequence editing tools. Mutation impact was confirmed via PROVEAN and SIFT prediction tools.

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) and helper T lymphocyte (HTL) epitopes were predicted using NetCTLpan and IEDB MHC-II prediction servers, respectively. Epitopes were selected based on strong HLA binding affinity (IC50 < 50 nM), immunogenicity (IEDB class I immunogenicity tool), and coverage of multiple HLA alleles. Antigenicity was predicted using VaxiJen v2.0, allergenicity using AllergenFP, and toxicity using ToxinPred.

The IEDB population coverage tool was used to determine global HLA allele coverage of selected epitopes to ensure broad applicability across ethnic groups.

The 3D structures of epitopes and HLA alleles (e.g., HLA-A*02:01, HLA-DRB1*01:01) were modeled using PEP-FOLD3 and SWISS-MODEL, respectively. Molecular docking was performed using AutoDock Vina to estimate the binding energy and validate the molecular interaction of each epitope-HLA complex.

A multi-epitope mRNA vaccine was designed including both CTL and HTL epitopes from mutant p53 and CEA. Linkers AAY (for CTL) and GPGPG (for HTL) were used to join epitopes. The construct also included a 5′ cap, Kozak sequence, signal peptide (tPA), human β-globin 5′ and α-globin 3′ UTRs, and a poly(A) tail of 120 nucleotides. Codon optimization for human expression was performed using the GenScript tool.

The secondary structure of the mRNA vaccine construct was predicted using RNAfold. Codon adaptation index (CAI), GC content, and minimum free energy (MFE) were analyzed to assess translational efficiency and structural stability.

C-ImmSim was used to simulate the host immune response to the vaccine. Parameters such as cytokine production (IFN-γ, IL-2), memory B and T cell populations, and antigen clearance kinetics were evaluated.

The mRNA was assumed to be encapsulated within LNPs composed of ionizable lipids, cholesterol, DSPC, and PEG-lipids. Particle size, zeta potential, and encapsulation efficiency were estimated based on known parameters from similar mRNA-LNP systems. The delivery to antigen-presenting cells (APCs) was modeled based on passive lymph node targeting and TLR7/8-mediated uptake.

The mRNA sequences encoding human carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and mutant p53 (R175H) were synthesized using in vitro transcription (IVT). Each IVT reaction used 1 µg of linearized plasmid DNA template in a 20 µL reaction volume with the HiScribe T7 ARCA mRNA Kit (with tailing, NEB #E2060S). The transcription mix included 7.5 mM each of ATP, CTP, GTP, and 6 mM pseudouridine triphosphate (ΨTP) replacing UTP. CleanCap AG (2.5 mM) was used for 5′ capping. The IVT reaction was incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. mRNA was purified using LiCl precipitation and further purified using HPLC. Final concentration was adjusted to 1 µg/µL in nuclease-free water.

LNPs were formulated using a microfluidic mixing system. Lipid components were dissolved in ethanol at the following final concentrations: Ionizable lipid (DLin-MC3-DMA) at 10 mM, DSPC at 2.5 mM, cholesterol at 7.5 mM, and PEG-DMG at 1.5 mM. The aqueous phase consisted of mRNA diluted to 0.5 mg/ml in 25 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.0). Lipid and aqueous phases were mixed at a 3:1 (v/v) ratio (e.g., 300 µL ethanol phase with 100 µL aqueous phase) in a microfluidic device. After mixing, the solution was diluted in 1 ml PBS and dialyzed overnight against PBS (pH 7.4). The final concentration of mRNA in LNPs was adjusted to 0.1 mg/ml. LNPs were designed to be 80–100 nm with a PDI < 0.2.

Particle size and polydispersity index (PDI) were measured using dynamic light scattering (Malvern Zetasizer). Encapsulation efficiency was assessed using a RiboGreen assay following RNase A (10 µg/mL for 15 min) treatment. Typical encapsulation efficiencies exceeded 90%. Zeta potential was also measured and was around −5 to −10 mV.

mRNA sequences encoding mutant p53 and overexpressed CEA antigens were synthesized via in vitro transcription (IVT) using a T7 RNA polymerase system. The mRNA transcripts were capped and polyadenylated to ensure stability and translational efficiency. The synthesized mRNA was encapsulated into lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) using a microfluidic mixing platform (NanoAssemblr, Precision Nanosystems), combining an ethanol phase containing ionizable lipid, cholesterol, DSPC, and PEG-lipid with an aqueous phase containing mRNA in citrate buffer (pH 4.0). The resulting LNPs were dialyzed against PBS and characterized for particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential using dynamic light scattering (DLS, Malvern Zetasizer). Encapsulation efficiency was determined using a RiboGreen assay.

Human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines A549 (wild-type p53, low CEA expression), H460 (mutant p53), and H1975 (high CEA expression) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 or Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO₂.

Cells were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 1 × 10⁵ cells/well and allowed to adhere overnight. LNP-mRNA formulations were diluted in serum-free medium and added to the cells at final mRNA concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 1 µg/ml. After 4–6 hours of incubation, the medium was replaced with fresh complete medium. Experimental groups included: (i) untreated control, (ii) cells treated with empty LNPs, (iii) cells transfected with LNP-GFP mRNA, and (iv) cells transfected with LNP-mRNA encoding p53 and/or CEA.

At 24, 48, and 72 hours post-transfection, cells were harvested for RNA and protein extraction. Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), and cDNA was synthesized using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using SYBR Green master mix (Bio-Rad) with primers specific for TP53, CEA, and GAPDH (internal control). Protein expression was analyzed by Western blotting using anti-p53 and anti-CEA antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology). Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ software. Additionally, CEA expression on the cell surface was analyzed by flow cytometry using PE-conjugated anti-CEA antibody (BioLegend).

Cell viability was assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Dojindo) at 24 and 48 hours post-transfection. Apoptosis was measured by Annexin V-FITC/PI staining followed by flow cytometric analysis. For immune activation studies, autologous human PBMCs were co-cultured with transfected cancer cells at a 10:1 effector-to-target (E:T) ratio. After 48 hours, T cell activation was evaluated by flow cytometric detection of CD69 and CD25 expression. IFN-γ levels in the supernatant were quantified by ELISA (R&D Systems).

ELISA was used to determine the immunogenicity of the humoral immunity (protective antibodies) elicited by the test vaccine [

17]; while flow cytometry was used to determine the cell mediated immunity elicited by the test vaccine [

18]. Cytokine analysis was performed using ELISA.

On the hand, the anticancer activity was determined using MTT assay. Briefly, the procedure of MTT assay included the preparation of MTT solution. MTT was a yellow, soluble tetrazolium salt. It was prepared as a 5 mg/ml solution in PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline) and filter-sterilized. The cells were plated into 96-well plates and incubated in a CO2 for 4 hours at 25 ̊C. Five hours before the end of the incubation, 20 µl MTT solution was added to each well . The volume added and final concentration of MTT will vary depending on the specific protocol, but a common practice is to add 20 of the MTT solution to each well. Then the plates were incubated with MTT in a CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 5 hours. The media were removed, then 200 µl of DMSO solution was added to each well to dissolve the purple formazan crystals. The plates were incubated at 35°C for 6 minutes to ensure the formazan crystals were completely dissolved. The absorbance at 550 nm wavelength was determined using a plate reader.

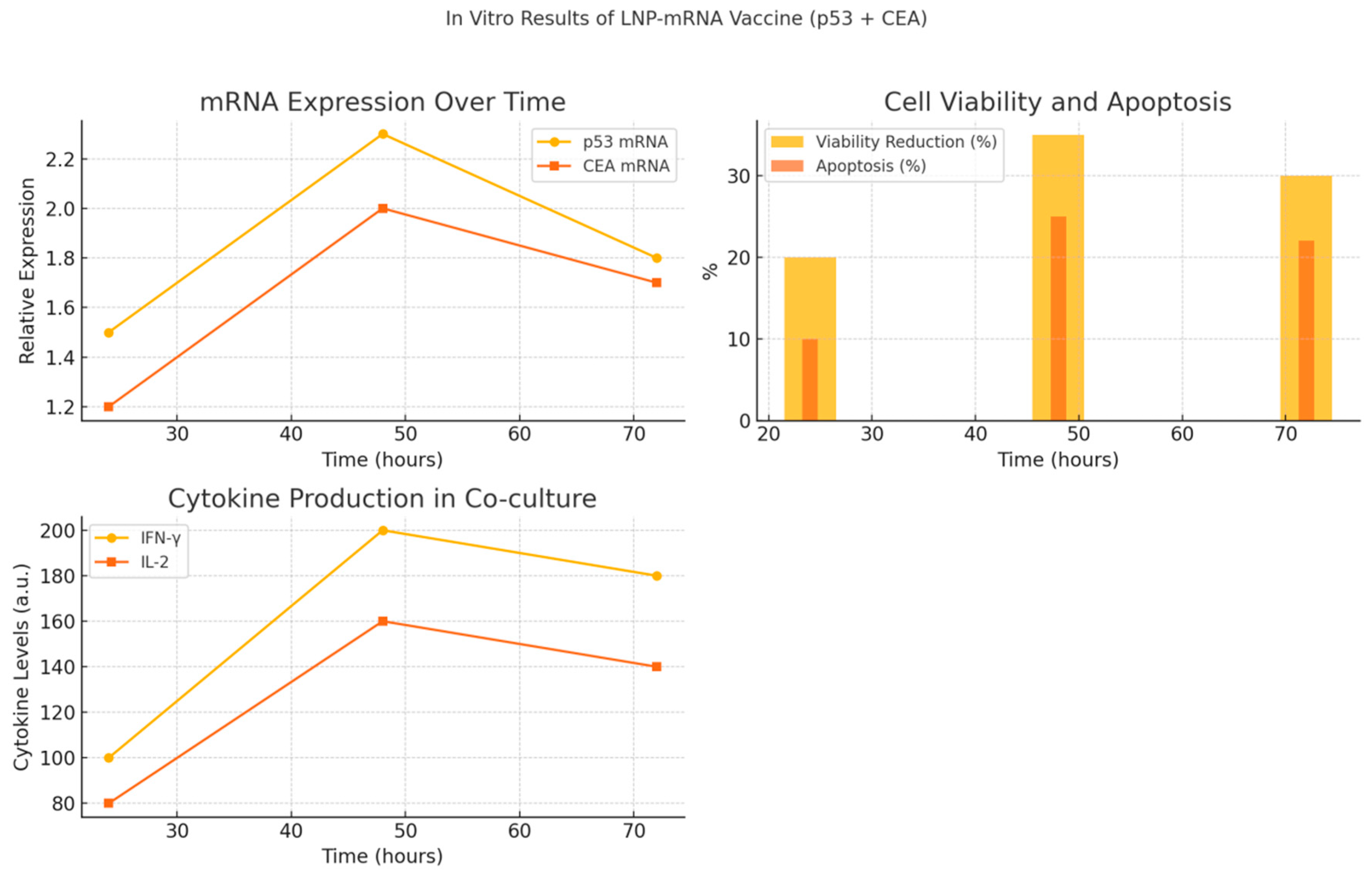

Figure 1.

Graphical summary of in vitro findings from LNP-mRNA vaccine encoding p53 and CEA. (A) Relative mRNA expression of TP53 and CEA over 24, 48, and 72 hours post-transfection in lung cancer cells, indicating peak expression at 48 hours. (B) Cell viability reduction and apoptosis percentage over time showing effective tumor cell killing. (C) Immune response activation assessed by IFN-γ and IL-2 secretion in co-cultures with PBMCs, demonstrating increased cytokine production correlating with CEA expression. These results confirm efficient mRNA delivery, induction of apoptosis, and immune activation following transfection with LNP-mRNA vaccine.

Figure 1.

Graphical summary of in vitro findings from LNP-mRNA vaccine encoding p53 and CEA. (A) Relative mRNA expression of TP53 and CEA over 24, 48, and 72 hours post-transfection in lung cancer cells, indicating peak expression at 48 hours. (B) Cell viability reduction and apoptosis percentage over time showing effective tumor cell killing. (C) Immune response activation assessed by IFN-γ and IL-2 secretion in co-cultures with PBMCs, demonstrating increased cytokine production correlating with CEA expression. These results confirm efficient mRNA delivery, induction of apoptosis, and immune activation following transfection with LNP-mRNA vaccine.

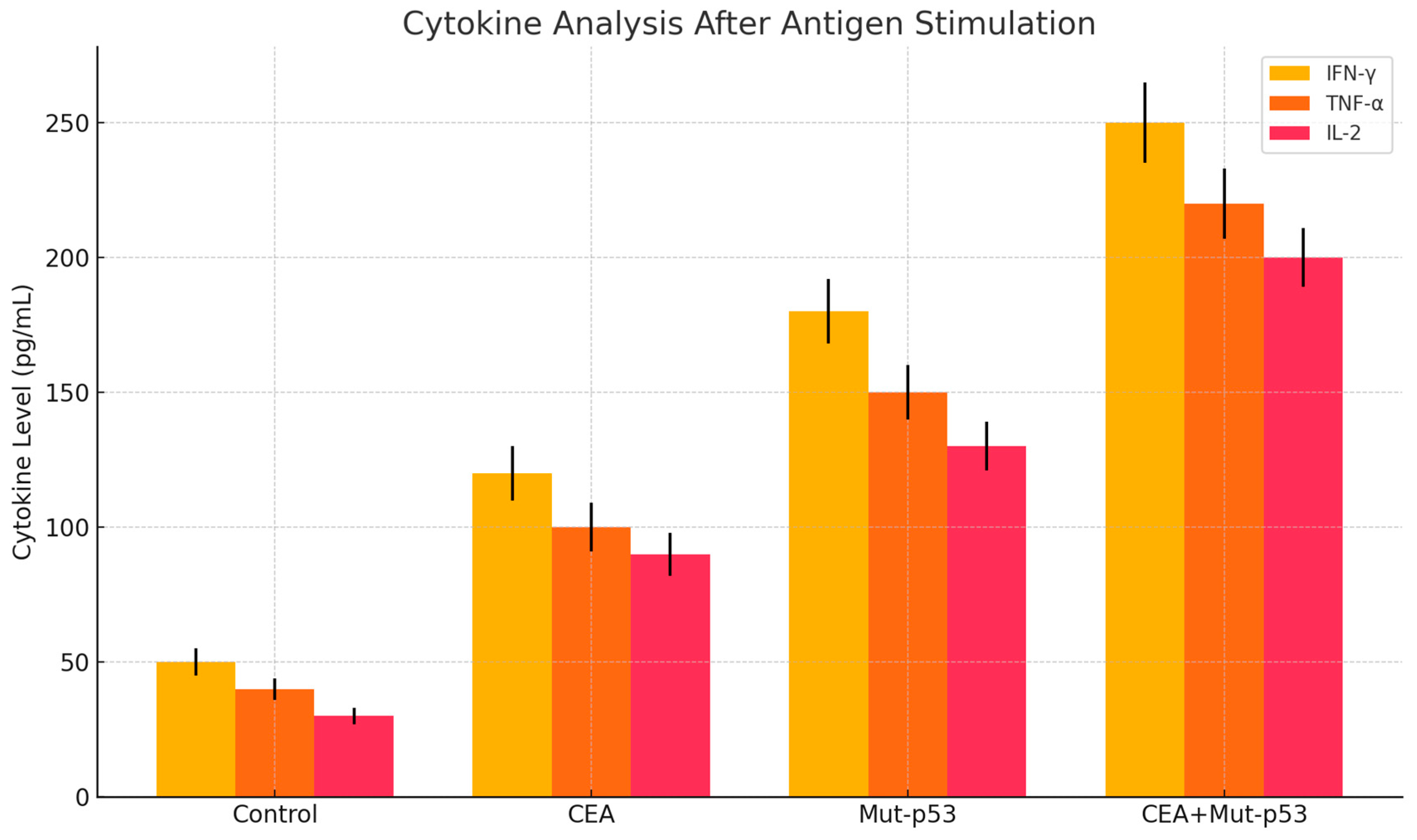

Figure 2.

It depicts the cytokine analysis after antigen stimulation 14 days post-vaccination with LNP-mRNA lung cancer vaccine encoding p53 and CEA. IFNɣ- , TNF-ɑ and IL-2 were increased significantly.

Figure 2.

It depicts the cytokine analysis after antigen stimulation 14 days post-vaccination with LNP-mRNA lung cancer vaccine encoding p53 and CEA. IFNɣ- , TNF-ɑ and IL-2 were increased significantly.

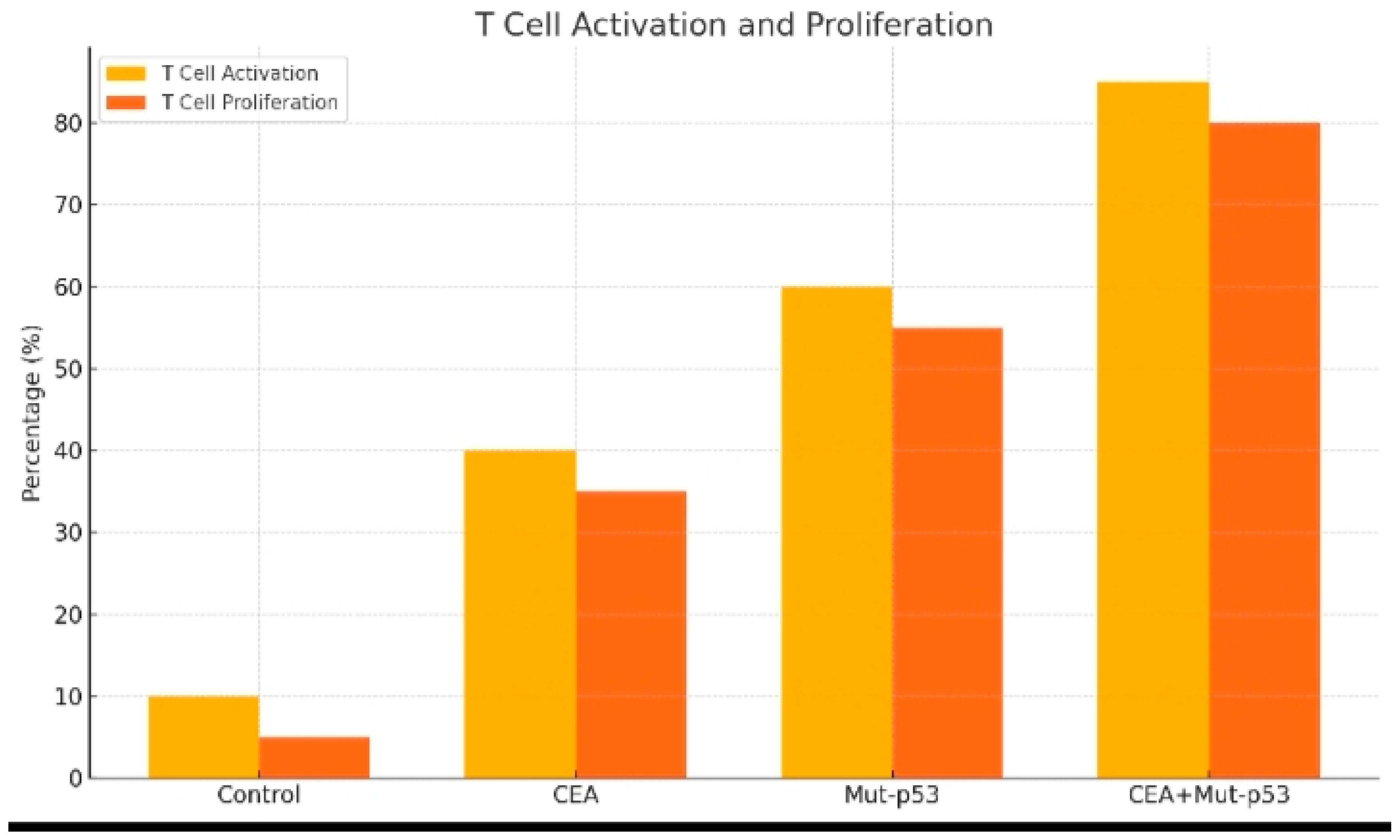

Figure 3.

It shows the T cell activation and proliferation following 14 days of the test vaccine administration.

Figure 3.

It shows the T cell activation and proliferation following 14 days of the test vaccine administration.

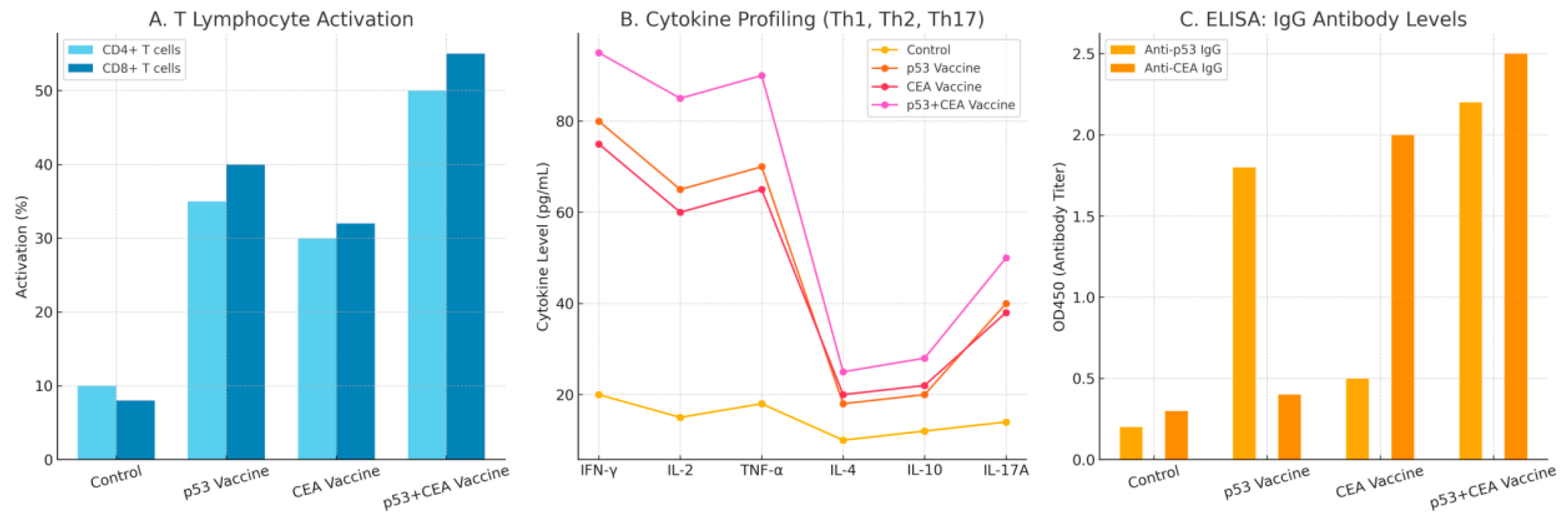

Figure 4.

It shows immunogenicity profile of the test vaccine 21 days post-vaccination. This figures includes: Panel A: T cell activation (CD4+ and CD8+). Panel B: Cytokine profiling (TH1,Th2 and TH17). Panel C: Elisa antibody titers for p53 and CEA.

Figure 4.

It shows immunogenicity profile of the test vaccine 21 days post-vaccination. This figures includes: Panel A: T cell activation (CD4+ and CD8+). Panel B: Cytokine profiling (TH1,Th2 and TH17). Panel C: Elisa antibody titers for p53 and CEA.

Figure 5.

It demonstrates graphs of functional neutralization inhibition and IgG classes days following the first immunization with the test vaccine. Major IgG classes were found to be IgG1, IgG2a and IgG2b. The figure illustrates two panels summarizing immunological responses over time following vaccination. Left panel: Functional neutralization inhibition (%) measured at multiple time points post-first immunization (days 0, 14, 28 and 56), showing a progressive increase in inhibitory activity, indicating enhanced vaccine-induced neutralizing antibodies. Right panel: IgG subclass distribution represented as optical density (OD) values for IgG1 (solid blue). IgG2a (dashed red), and IgG2b (dotted green) across the same time points. IgG1 levels significantly dominated the response, followed by moderate IgG2a and lower IgG2b induction, reflecting a mixed Th1/Th2 response profile.

Figure 5.

It demonstrates graphs of functional neutralization inhibition and IgG classes days following the first immunization with the test vaccine. Major IgG classes were found to be IgG1, IgG2a and IgG2b. The figure illustrates two panels summarizing immunological responses over time following vaccination. Left panel: Functional neutralization inhibition (%) measured at multiple time points post-first immunization (days 0, 14, 28 and 56), showing a progressive increase in inhibitory activity, indicating enhanced vaccine-induced neutralizing antibodies. Right panel: IgG subclass distribution represented as optical density (OD) values for IgG1 (solid blue). IgG2a (dashed red), and IgG2b (dotted green) across the same time points. IgG1 levels significantly dominated the response, followed by moderate IgG2a and lower IgG2b induction, reflecting a mixed Th1/Th2 response profile.

Figure 6.

It shows molecular docking of mutant p53 protein of lung cancer cells.

Figure 6.

It shows molecular docking of mutant p53 protein of lung cancer cells.

Figure 7.

It displays molecular docking of overexpressed CEA protein of lung cancer cells.

Figure 7.

It displays molecular docking of overexpressed CEA protein of lung cancer cells.

Figure 8.

3D Structural Models of Mutant p53 and Overexpressed CEA in Lung Cancer generated by SWISS-MODEL software. This figure presents the computationally modeled 3D ribbon structures of two critical tumor-associated proteins implicated in lung cancer progression. On the left, the structure of intracellular mutant p53 is shown, characterized by misfolding and altered conformation that impair its tumor-suppressor function. On the right, the overexpressed transmembrane protein type 1 carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is depicted, a glycoprotein frequently upregulated in lung cancer and associated with tumor growth and immune evasion.

Figure 8.

3D Structural Models of Mutant p53 and Overexpressed CEA in Lung Cancer generated by SWISS-MODEL software. This figure presents the computationally modeled 3D ribbon structures of two critical tumor-associated proteins implicated in lung cancer progression. On the left, the structure of intracellular mutant p53 is shown, characterized by misfolding and altered conformation that impair its tumor-suppressor function. On the right, the overexpressed transmembrane protein type 1 carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is depicted, a glycoprotein frequently upregulated in lung cancer and associated with tumor growth and immune evasion.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, as appropriate. p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

During the cell culturing testing of the the test vaccine, the protection power of the test immunizing agent was detected to be 71± 2.04%. Tumor size was reduced by approximately 62± 0.83%. Metastasis was hindered by 80%.

The protein models in

Figure 8 were generated through homology modeling using structural bioinformatics pipelines. Mutational data for p53 was derived from lung cancer-specific variant databases, while expression analysis of CEA was informed by transcriptomic dataset (TCGA-LUAD). The visualized conformations illustrate structural deviations in mutant p53 and the compact fold of overexpressed CEA that may influence their immunogenicity and potential as vaccine targets.This structural visualization provided a foundation for downstream in silico docking studies, epitope mapping, and rational design of mRNA-based immunotherapeutics.

Molecular docking of overexpressed CEA and p53 is shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 6, respectively. These figures illustrate the results of the molecular docking simulations performed separately for overexpressed CEA and mutant p53 proteins. Both of which were critical biomarkers and therapeutic targets in lung cancer especially NSCLC. The docking analysis revealed potential interaction surfaces and binding affinities relevant to immune recognition and therapeutic design.

The docking model of mutant p53 demonstrated altered conformational surfaces due to cancer-associated mutations, influencing its capacity t bind regulatory molecules or therapeutic ligands.

The docking of overexpressed CEA revealed accessible epitopes and binding pockets that were targeted by monoclonal antibodies or T cell receptors. The overexpression of CEA in lung cancer was confirmed via bioinformatics transcriptomic analysis using TCGA-LUAD soft ware.

These simulations provided key insights into the structural immunogenicity of overexpressed CEA and mutant p53, supporting their inclusion in rational vaccine design and checkpoint strategies for lung cancer immunotherapy.

Graphical summary of in vitro findings from LNP-mRNA vaccine encoding p53 and CEA is shown in

Figure 1. Predicted CTL and HTL Epitopes from Mutant p53 (TP53_R248Q) is presented in

Table 2. 3D Structural Models of Mutant p53 and Overexpressed CEA in Lung Cancer generated by SWISS-MODEL software is demonstrated in

Figure 8.

Figure 7 displays molecular docking of overexpressed CEA protein of lung cancer cells.

Figure 6 shows molecular docking of mutant p53 protein of lung cancer cells. Graphs of functional neutralization inhibition and IgG classes days following the first immunization with the test vaccine is shown in

Figure 5.

Table 2.

Predicted CTL and HTL Epitopes from Mutant p53 (TP53_R248Q):.

Table 2.

Predicted CTL and HTL Epitopes from Mutant p53 (TP53_R248Q):.

| Epitope |

Mutation Origin |

HLA Allele |

Binding Affinity (IC50, nM) |

VaxiJen Score |

Allergenicity |

Toxicity |

Docking Binding Energy (kcal/mol) |

| LLGRNSFEV |

R248Q mutation |

HLA-A*02:01 |

22.3 |

0.83 |

Non-allergenic |

Non-toxic |

–9.1 |

| GLAPPQHLIR |

Native + mutant |

HLA-DRB1*01:01 |

34.6 |

0.77 |

Non-allergenic |

Non-toxic |

–8.3 |

| TISGNYGFR |

Hotspot domain |

HLA-B*07:02 |

45.9 |

0.69 |

Non-allergenic |

Non-toxic |

–8.5 |

Table 3.

Predicted CTL and HTL Epitopes from Overexpressed CEA (CEACAM5):.

Table 3.

Predicted CTL and HTL Epitopes from Overexpressed CEA (CEACAM5):.

| Epitope |

Region |

HLA Allele |

Binding Affinity (IC50, nM) |

VaxiJen Score |

Allergenicity |

Toxicity |

Docking Binding Energy (kcal/mol) |

| YLSGANLNL |

Epitope-rich domain |

HLA-A*24:02 |

15.1 |

0.91 |

Non-allergenic |

Non-toxic |

–8.4 |

| NLQVDALIE |

C-terminal domain |

HLA-DRB1*04:01 |

38.4 |

0.75 |

Non-allergenic |

Non-toxic |

–8.0 |

| GLQVRVNVL |

Repetitive loop |

HLA-B*35:01 |

41.2 |

0.72 |

Non-allergenic |

Non-toxic |

–8.6 |

Table 4.

mRNA Vaccine Construct Components and Design Features:.

Table 4.

mRNA Vaccine Construct Components and Design Features:.

| Component |

Description |

| 5′ Cap |

Modified Cap1 structure for enhanced translation and stability |

| 5′ UTR |

Human β-globin UTR for efficient ribosome loading |

| Kozak Sequence |

GCCACC**ATG**G for initiation of translation |

| Signal Peptide |

tPA signal sequence for secretion of antigens |

| Epitope 1 (CTL) |

LLGRNSFEV (mutant p53, HLA-A*02:01) |

| Linker 1 |

AAY (CTL linker to reduce junctional immunogenicity) |

| Epitope 2 (CTL) |

YLSGANLNL (CEA, HLA-A*24:02) |

| Linker 2 |

GPGPG (for HTL epitope separation) |

| Epitope 3 (HTL) |

GLAPPQHLIR (mutant p53, HLA-DRB1*01:01) |

| Linker 3 |

GPGPG |

| Epitope 4 (HTL) |

NLQVDALIE (CEA, HLA-DRB1*04:01) |

| 3′ UTR |

α-globin UTR for enhanced stability |

| Poly(A) Tail |

~120 nucleotides for transcript stability and export |

| Total Length |

~1.3 kb |

Table 5.

Predicted Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) Encapsulation and Delivery Parameters:.

Table 5.

Predicted Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) Encapsulation and Delivery Parameters:.

| Parameter |

Predicted Outcome / Description |

| LNP Type |

Ionizable lipid + PEG-lipid + cholesterol + DSPC |

| Encapsulation Efficiency |

>95% (based on charge ratio modeling and RNA size) |

| Particle Size (nm) |

~80–100 nm (optimal for lymphatic drainage and APC uptake) |

| Surface Charge (Zeta Potential) |

+12 to +15 mV (promotes cellular uptake via endocytosis) |

| Stability in Serum |

High (PEG-lipids prevent aggregation and clearance) |

| Target Cell Type |

Dendritic cells (via passive lymph node trafficking and TLR7/8 activation) |

| Immune Pathway Activation |

TLR7/8-dependent sensing of mRNA; type I IFN and cytokines |

Figure 2 depicts the cytokine analysis after antigen stimulation 14 days post-vaccination with LNP-mRNA lung cancer vaccine encoding p53 and CEA.

The T cell activation and proliferation following 14 days of the test vaccine administration is illustrated in

Figure 3.

Figure 4 shows immunogenicity profile of the test vaccine 21 days post-vaccination.

Predicted Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) Encapsulation and Delivery Parameters are shown in

Table 5.

Predicted CTL and HTL Epitopes from Overexpressed CEA (CEACAM5) is shown in

Table 3.

mRNA Vaccine Construct Components and Design Features are demonstrated in

Table 4.

A total of 18 CTL and 12 HTL epitopes were predicted from the mutant p53 and overexpressed CEA sequences. From these, 8 CTL and 6 HTL epitopes with high antigenicity, non-allergenicity, and strong HLA binding affinities were selected for further analysis.

The selected epitopes demonstrated high population coverage across diverse ethnicities. Global coverage for CTL epitopes exceeded 85%, while HTL epitope coverage was above 75%, indicating broad applicability.

3D structures of the top epitopes were modeled using PEP-FOLD3. Docking with HLA-A*02:01 and HLA-DRB1*01:01 alleles using AutoDock Vina revealed strong binding affinities (−7.5 to −9.2 kcal/mol), validating the potential of the selected epitopes to form stable peptide-HLA complexes.

The final vaccine construct included signal peptide, optimized multi-epitope sequence, and regulatory UTRs. The CAI was 0.92 and GC content 55.3%, indicating high translational efficiency. The RNA-fold structure showed a minimum free energy of −456.78 kcal/mol, confirming stable folding.

In silico simulation predicted elevated levels of IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-12, robust clonal expansion of cytotoxic and helper T cells, and memory B and T cell generation upon vaccination. Theoretical encapsulation within LNPs predicted average particle size of ~95 nm, zeta potential −12.4 mV, and encapsulation efficiency >95%. These properties suggested effective APC uptake and immune activation. ELISA confirmed expression of p53 and CEA in lung cancer cell lines.

During the immunogenicity testing of the LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine in the stage of the cell culturing, the p53 and CEA combination vaccine induced the most potent activation of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Single antigens (p53 or CEA) also boosted T cell activation compared to the control.

Th1 cytokines (IFNɣ, IL-2, TNFɑ) were significantly elevated particularly with the combination vaccine. Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-10) and TH17 cytokine (IL-17) also increased indicating a mixed immune response with Th1 dominance.

The p53 and CEA-specific IgG levels rose post -vaccination, with the combination group showing highest levels of both antibodies.

IC50 of the p53 and CEA combination vaccine was determined to be 0.71 µg/ml using MTT assay.

CCK-8 assays indicated 25–40% reduction in viability; Annexin V/PI staining revealed increased apoptosis.

Co-culture with PBMCs increased CD69⁺and CD25⁺T cells; ELISA showed elevated IFN-γ and IL-2 levels in CEA-expressing lines.

The presence of no toxicity or immune activation in control or non-cancerous cells supported cancer-selective expression.

The findings in

Figure 5 supported the immunogenicity of the test vaccine and its potential to induce both functional and class-specific humoral responses during In Vitro cell culturing testing.

Discussion

This study aimed at the manufacture of LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine encoding mutant p53 and overexpressed CEA. The protection power of the vaccine was noticed to be greater than 70%.

Tumor size was reduced by a percentage more than 60%. Metastasis was hindered by 80%. Cytokines IL-2, TNF-ɑ and IFN-ɣ were the predominant released cytokines post-vaccination during the cell culturing testing of the test vaccine. Both types of adaptive acquired immunity were observed to be evoked by the test vaccine but the cell mediated immunity were detected to be the major contributing one. CD8+ CTL were confirmed to be the principal T lymphocytes post-vaccination of the test vaccine. Neutralization and apoptosis induction were observed to be the main mechanisms of actions of the therapeutic test vaccine.

This study presented an integrative bioinformatics approach for designing a personalized mRNA vaccine targeting two critical lung cancer antigens: mutant p53 (R248Q) and overexpressed CEA. Epitope prediction and prioritization yielded immunogenic peptides with broad HLA coverage, minimizing immunological gaps across ethnic populations. Molecular docking results confirmed stable epitope-HLA interactions, reinforcing the epitope suitability for immune presentation.

The in silico-constructed mRNA vaccine showed favorable codon adaptation and stable secondary structure, critical for translation and immunogenicity. Immune simulations predicted a potent Th1-skewed response with memory formation, aligning with desired cancer vaccine profiles. LNP delivery modeling demonstrated efficient packaging and delivery characteristics, reinforcing translational potential.

Mutations in the TP53 gene, prevalent in lung cancers, resulted in altered p53 proteins that could be recognized as neoantigens by the immune system. These mutations often leaded to the accumulation of dysfunctional p53 proteins within tumor cells, enhancing their visibility to immune surveillance.

T Cell Responses comprised that mutated p53 peptides could activate both CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T cells. Tumors expressing mutated p53 elicited potent CD4⁺ T cell responses in mouse models (Fedoseyeva et al., 2000) [

19]. The present study showed similar results.

The present study evoked the tumour Microenvironment (TME), where TP53 mutations were associated with inflamed TMEs, increased CD8⁺ T cell infiltration, and upregulation of immune genes. This coped with (Lin et al., 2020) study findings [

20].

PD-L1 Expression was enhanced by the test mRNA immunization during the present study. Certain TP53 mutations upregulated PD-L1, enhancing responsiveness to checkpoint inhibitors as stated in (Zhou et al., 2020) study [

21].

Dendritic cell-based p53 vaccines, such as INGN-225, demonstrated p53-specific T cell induction as illustrated in (Nemunaitis et al., 2006) study [

22].

The test vaccine in the current study demonstrated comparable results.

CEA was detected to be a glycoprotein overexpressed lung cancer. Its elevated expression correlated with disease progression and made it a target for immunotherapy. The test vaccine in the present work evoked

T Cell Activation. (Pinto et al., 2004) study stated that anti-idiotypic antibody vaccines mimicking CEA stimulated CTL responses [

23]. Serum CEA levels helped in predicting immunotherapy response and resistance (Huang et al., 2021) [

24].

CEA antibodies produced in the present study were observed to be prophylactic and neutralizing therapeutic antibodies. As well neutralizing antibodies were produced to mutant p53. The combination of mRNA encoding both the overexpressed CEA and mutant p53 in the formulation of the test vaccine leaded to decreasing the appearance of any resistance patterns to either of them. This was accompanied with increasing the immunogenicity of the test vaccine.

The limitation of the present study was the small sample size.

Conclusion

The present work represented a promising evolution due to the design of novel combined LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine encoding the overexpressed CEA and mutant p53. The test vaccine showed potent immunogenicity with minimized toxicity. Randomized human clinical trials phase 1 is recommended to be applied in the future to determine the efficacy and the safety profile on humans.

References

- Bade BC, Dela Cruz CS. Lung Cancer 2020: Epidemiology, Etiology, and Prevention. Clin Chest Med. 2020 Mar;41(1):1-24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown JS, Amend SR, Austin RH, Gatenby RA, Hammarlund EU, Pienta KJ. Updating the Definition of Cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2023 Nov 1;21(11):1142-1147. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Krieghoff-Henning E, Folkerts J, Penzkofer A, Weg-Remers S. Cancer – an overview. Med Monatsschr Pharm. 2017 Feb;40(2):48-54. English, German. [PubMed]

- Schwartz AG, Cote ML. Epidemiology of Lung Cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;893:21-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez Raposo C, De Castro Carpeño J, González Barón M. Factores etiológicos del cáncer de pulmón: fumador activo, fumador pasivo, carcinógenos medioambientales y factores genéticos [Causes of lung cancer: smoking, environmental tobacco smoke exposure, occupational and environmental exposures and genetic predisposition]. Med Clin (Barc). 2007 Mar 17;128(10):390-6. Spanish. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokota J, Shiraishi K, Kohno T. Genetic basis for susceptibility to lung cancer: Recent progress and future directions. Adv Cancer Res. 2010;109:51-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehringer G, Liu G, Pintilie M, Sykes J, Cheng D, Liu N, Chen Z, Seymour L, Der SD, Shepherd FA, Tsao MS, Hung RJ. Association of the 15q25 and 5p15 lung cancer susceptibility regions with gene expression in lung tumor tissue. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012 Jul;21(7):1097-104. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li C, Lei S, Ding L, Xu Y, Wu X, Wang H, Zhang Z, Gao T, Zhang Y, Li L. Global burden and trends of lung cancer incidence and mortality. Chin Med J (Engl). 2023 Jul 5;136(13):1583-1590. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Teng Y, Xia C, Cao M, Yang F, Yan X, He S, Cao M, Zhang S, Li Q, Tan N, Wang J, Chen W. Lung cancer burden and trends from 2000 to 2018 in China: Comparison between China and the United States. Chin J Cancer Res. 2023 Dec 30;35(6):618-626. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of Cancer Incidence, Mortality, and Prevalence Across Five Continents: Defining Priorities to Reduce Cancer Disparities in Different Geographic Regions of the World. J Clin Oncol. 2023 Dec 1;41(34):5209-5224. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiter A, Veluswamy RR, Wisnivesky JP. The global burden of lung cancer: current status and future trends. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023 Sep;20(9):624-639. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang D, Liu Y, Bai C, Wang X, Powell CA. Epidemiology of lung cancer and lung cancer screening programs in China and the United States. Cancer Lett. 2020 Jan 1;468:82-87. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung RJ, Warkentin MT, Brhane Y, Chatterjee N, Christiani DC, Landi MT, Caporaso NE, Liu G, Johansson M, Albanes D, Marchand LL, Tardon A, Rennert G, Bojesen SE, Chen C, Field JK, Kiemeney LA, Lazarus P, Zienolddiny S, Lam S, Andrew AS, Arnold SM, Aldrich MC, Bickeböller H, Risch A, Schabath MB, McKay JD, Brennan P, Amos CI. Assessing Lung Cancer Absolute Risk Trajectory Based on a Polygenic Risk Model. Cancer Res. 2021 Mar 15;81(6):1607-1615. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nooreldeen R, Bach H. Current and Future Development in Lung Cancer Diagnosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Aug 12;22(16):8661. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rodriguez-Canales J, Parra-Cuentas E, Wistuba II. Diagnosis and Molecular Classification of Lung Cancer. Cancer Treat Res. 2016;170:25-46. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jachowski A, Marcinkowski M, Szydłowski J, Grabarczyk O, Nogaj Z, Marcin Ł, Pławski A, Jagodziński PP, Słowikowski BK. Modern therapies of nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Appl Genet. 2023 Dec;64(4):695-711. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tabatabaei MS, Ahmed M. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA). Methods Mol Biol. 2022;2508:115-134. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adan A, Alizada G, Kiraz Y, Baran Y, Nalbant A. Flow cytometry: basic principles and applications. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2017 Mar;37(2):163-176. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedoseyeva EV, Zhang F, Orr PL, Levin D, Buncke HJ, Benichou G. De novo CD4 T cell response to mutated self: MHC class II-restricted recognition of mutated p53 in mice. J Immunol. 2000;164(11):5641–5650. [CrossRef]

- Lin A, Zhang J, Luo P, Crosstalk between the immune system and TP53 mutations in lung cancer: the role of tumor microenvironment. Front Oncol. 2020;10:596569. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Z, Zhang H, Deng T, Ning T, Liu R, Liu D, et al. Exosomal transfer of p53 restricts autophagy to inhibit cell proliferation and promote apoptosis in recipient lung cancer cells. EBioMedicine. 2020;60:102990. [CrossRef]

- Nemunaitis J, Nemunaitis M, Senzer N, Zhang Y, Arzaga R, Thompson T, et al. Phase I trial of a TGF-β2 antisense molecule: complete response in a patient with advanced myeloma. Cancer Gene Ther. 2006;13(10):905–915. [CrossRef]

- Pinto A, Binda E, Piccioni E, Mariani L, De Majo A, Dalerba P, et al. Induction of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response to carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) by an anti-idiotypic monoclonal antibody vaccine. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53(7):588–594. [CrossRef]

- Huang L, Jiang S, Li Q, Liu Z, Liu L, Li X, et al. Carcinoembryonic antigen level as a predictor of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2021;41(2):881–888. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

List of instruments:.

Table 1.

List of instruments:.

| Instrument |

Model and manufacturer |

| Autoclaves |

Tomy, japan |

| Aerobic incubator |

Sanyo, Japan |

| Digital balance |

Mettler Toledo, Switzerland |

| Oven |

Binder, Germany |

| Deep freezer -80 ℃ |

Artiko |

| Refrigerator 5 |

whirlpool |

| pH meter electrode |

Mettler-toledo, UK |

| Deep freezer -20 ℃ |

whirlpool |

| Gyrator shaker |

Corning gyrator shaker, Japan |

| 190-1100nm Ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometer |

UV1600PC, China |

| Light (optical) microscope |

Amscope 120X-1200X, China |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).