Statistical Analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplets. Their presentation was by means and standard deviation. One way analysis of variance( p value≤ 0.05) was used as means for performing statistical analysis and also, statistical analysis based on excel-spreadsheet-software. The student's t-test was used during the present study.

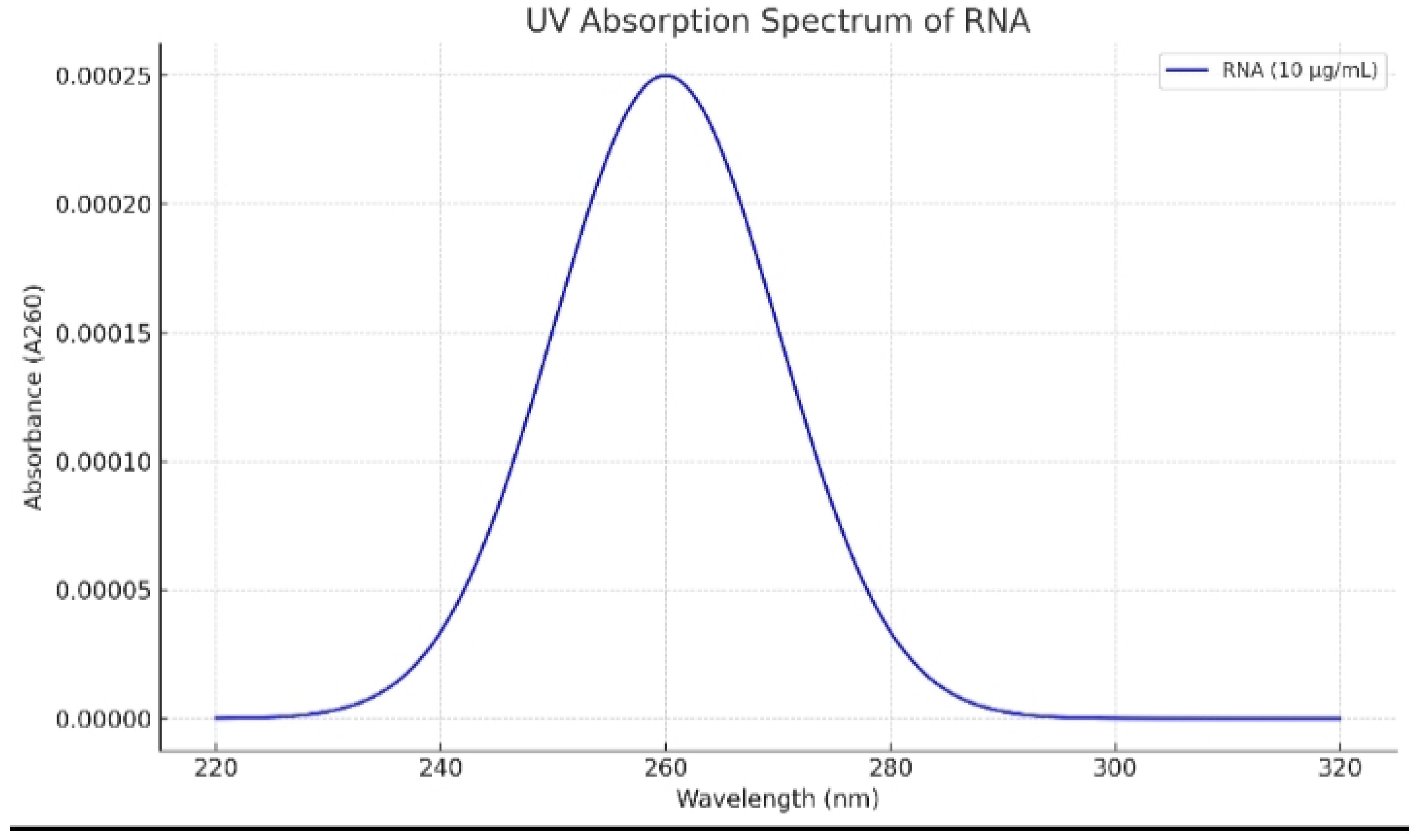

Figure 1.

UV absorption spectrum of mRNA of mutated KRAS protein of lung cancer cells. Peak absorbance was determined at 260 nm.

Figure 1.

UV absorption spectrum of mRNA of mutated KRAS protein of lung cancer cells. Peak absorbance was determined at 260 nm.

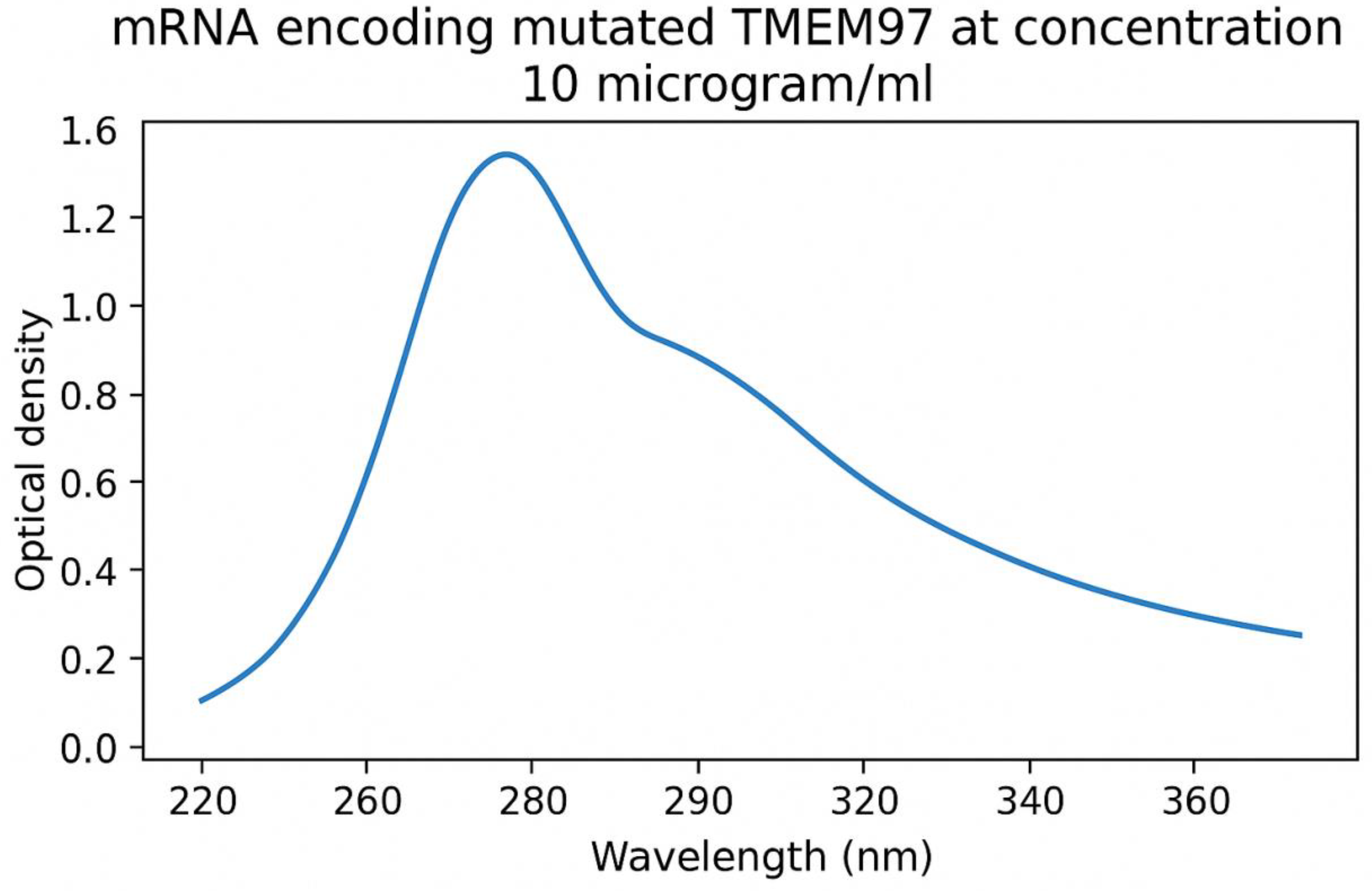

Figure 2.

UV absorption spectrum of mRNA of mutated TMEM97 protein of lung cancer cells. Peak absorbance was determined at 260 nm.

Figure 2.

UV absorption spectrum of mRNA of mutated TMEM97 protein of lung cancer cells. Peak absorbance was determined at 260 nm.

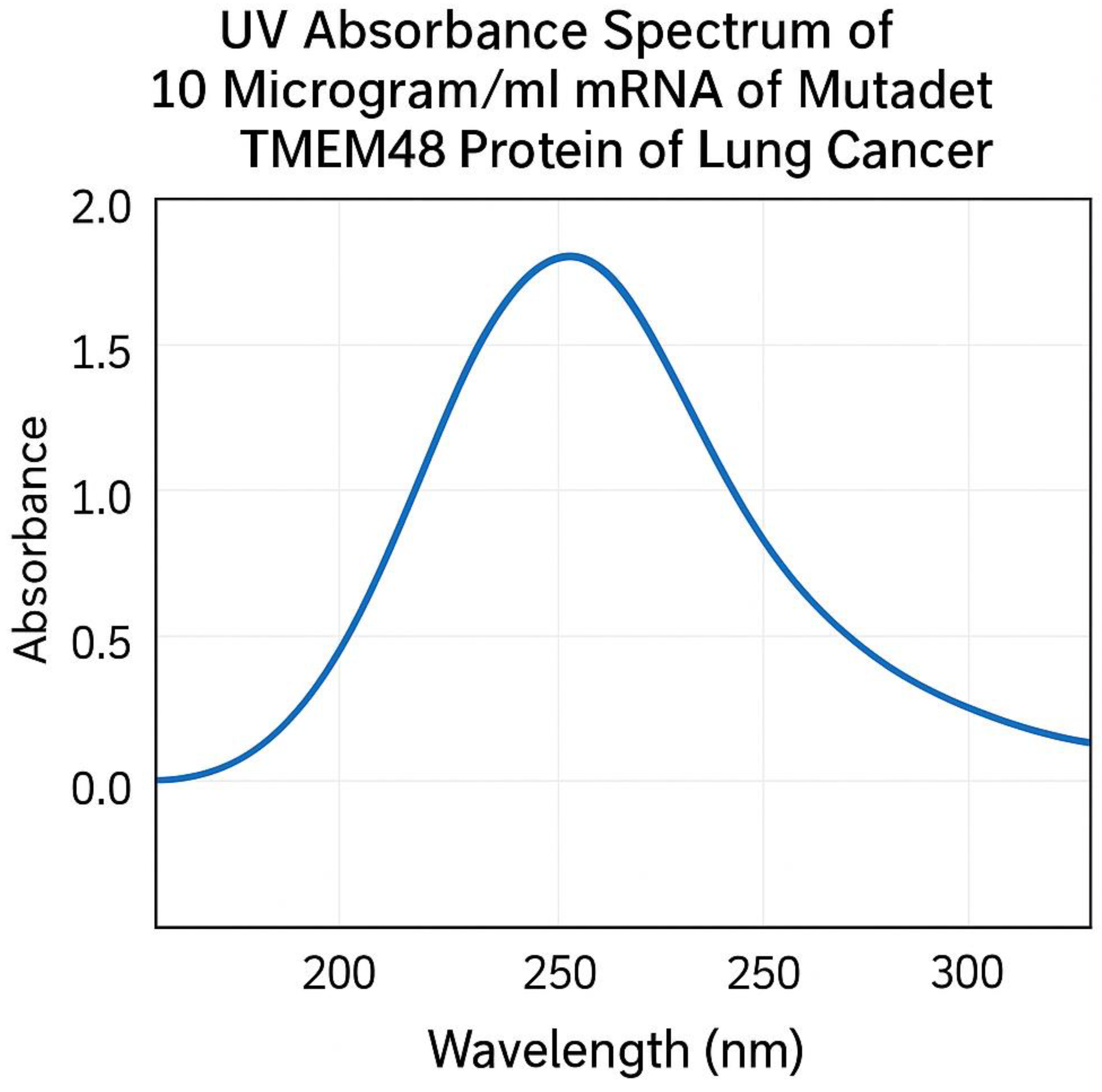

Figure 3.

UV absorption spectrum of mRNA of mutated TMEM48 protein of lung cancer cells. Peak absorbance was determined at 260 nm.

Figure 3.

UV absorption spectrum of mRNA of mutated TMEM48 protein of lung cancer cells. Peak absorbance was determined at 260 nm.

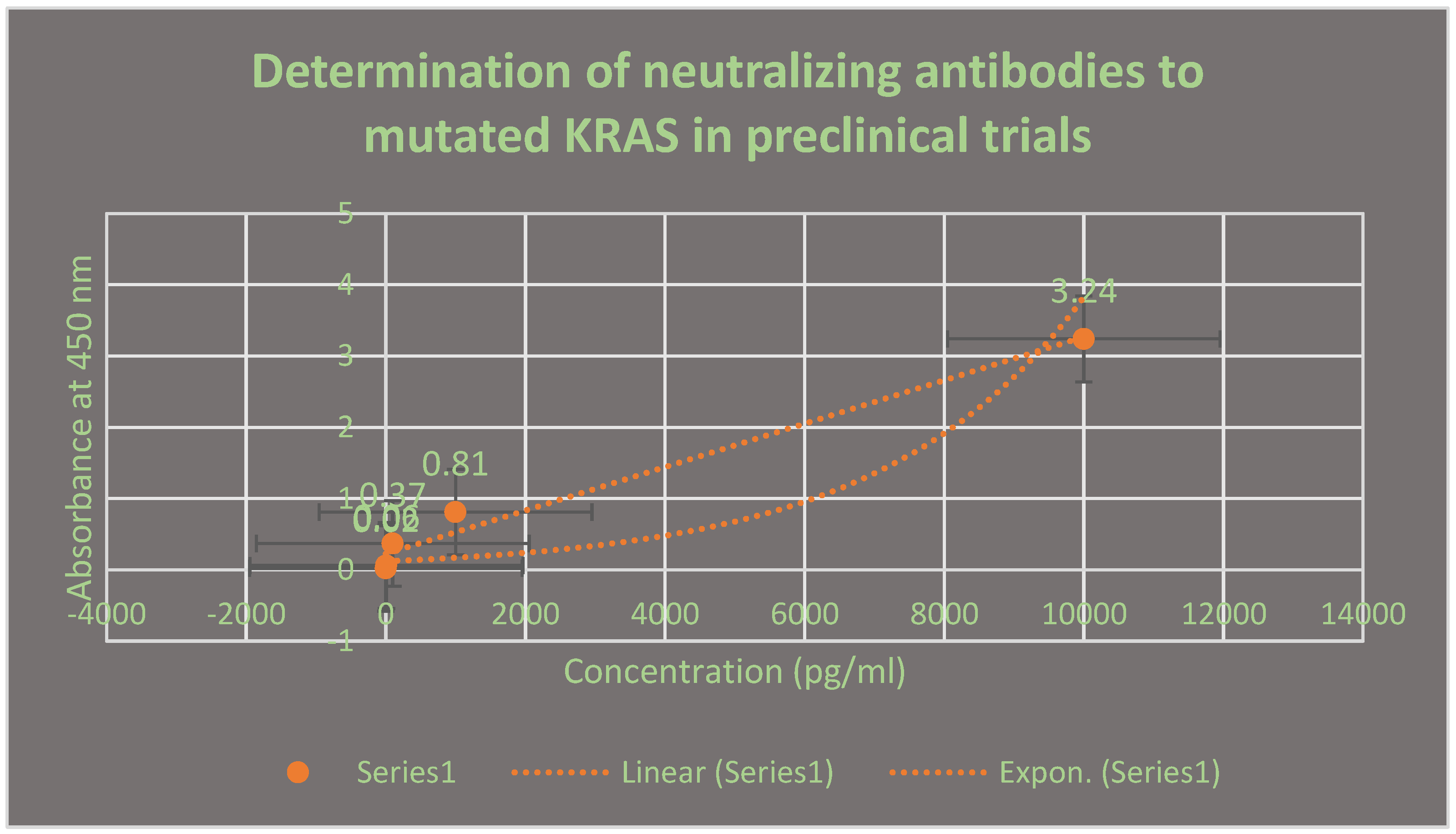

Figure 4.

It demonstrates the neutralizing antibodies to mutated lung cancer KRAS antigen using ELISA after 21 days. This assay was performed in preclinical trials stage.

Figure 4.

It demonstrates the neutralizing antibodies to mutated lung cancer KRAS antigen using ELISA after 21 days. This assay was performed in preclinical trials stage.

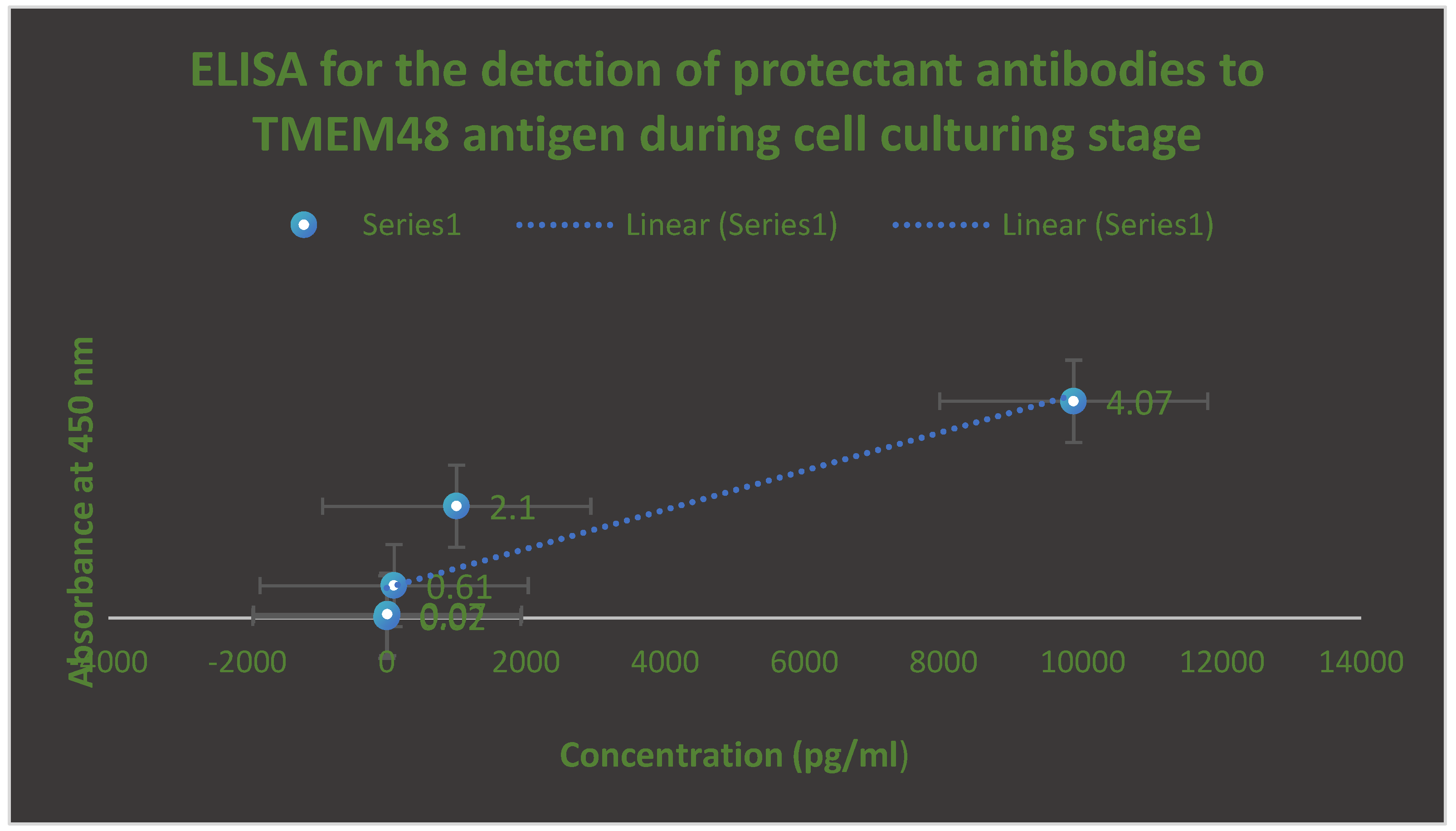

Figure 5.

It describes the determination of protectant antibodies to TMEM48 antigen on the surface of lung cancer cells using ELISA during cell culturing testing phase. The assay was performed after 14 days post-vaccination with the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine.

Figure 5.

It describes the determination of protectant antibodies to TMEM48 antigen on the surface of lung cancer cells using ELISA during cell culturing testing phase. The assay was performed after 14 days post-vaccination with the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine.

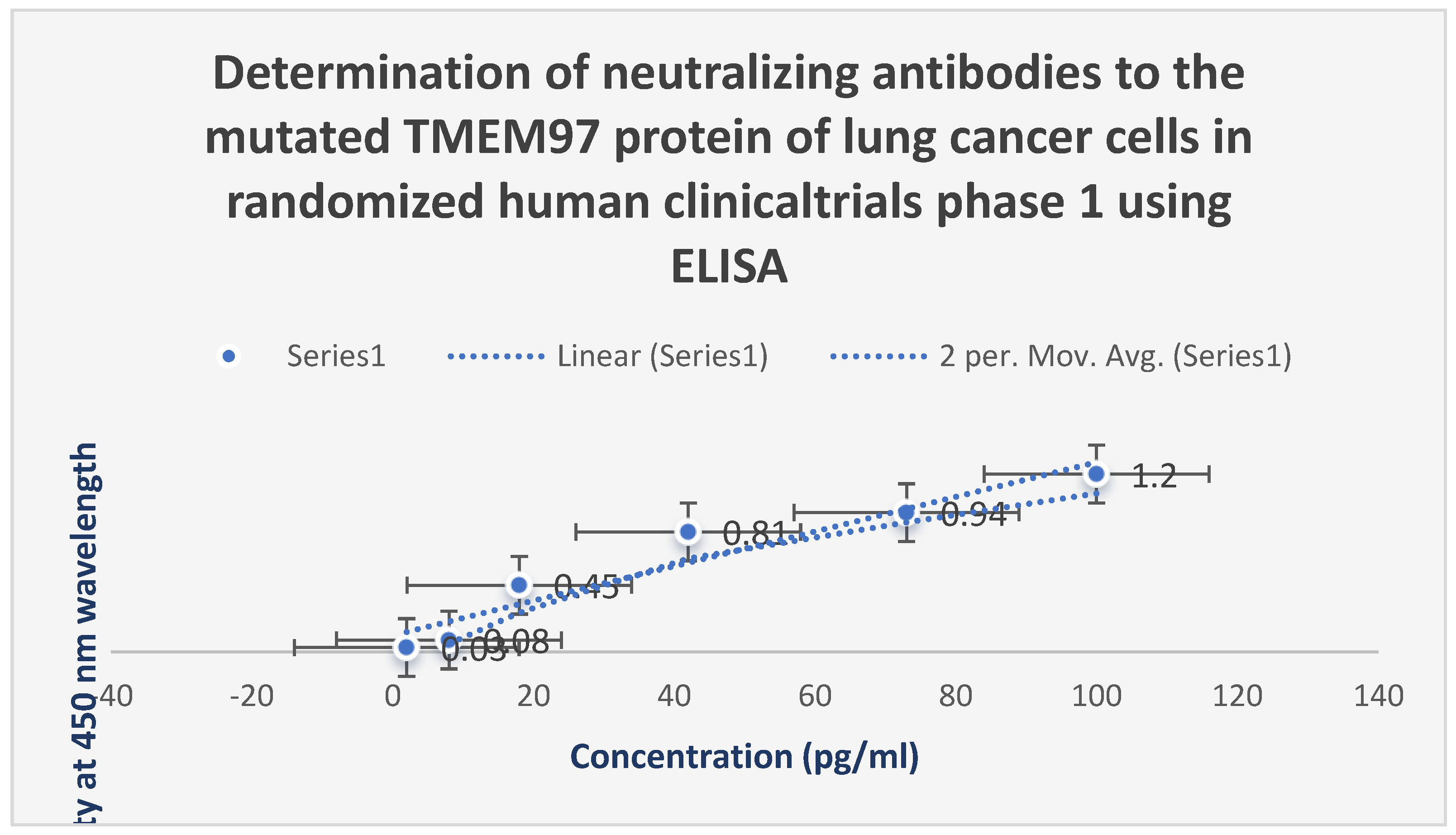

Figure 6.

It shows the assessment of the neutralizing antibodies to the mutated TMEM97 protein of lung cancer cells using ELISA during randomized human clinical trials phase 1. The appearance of these antibodies was observed after 28 days post-vaccination.

Figure 6.

It shows the assessment of the neutralizing antibodies to the mutated TMEM97 protein of lung cancer cells using ELISA during randomized human clinical trials phase 1. The appearance of these antibodies was observed after 28 days post-vaccination.

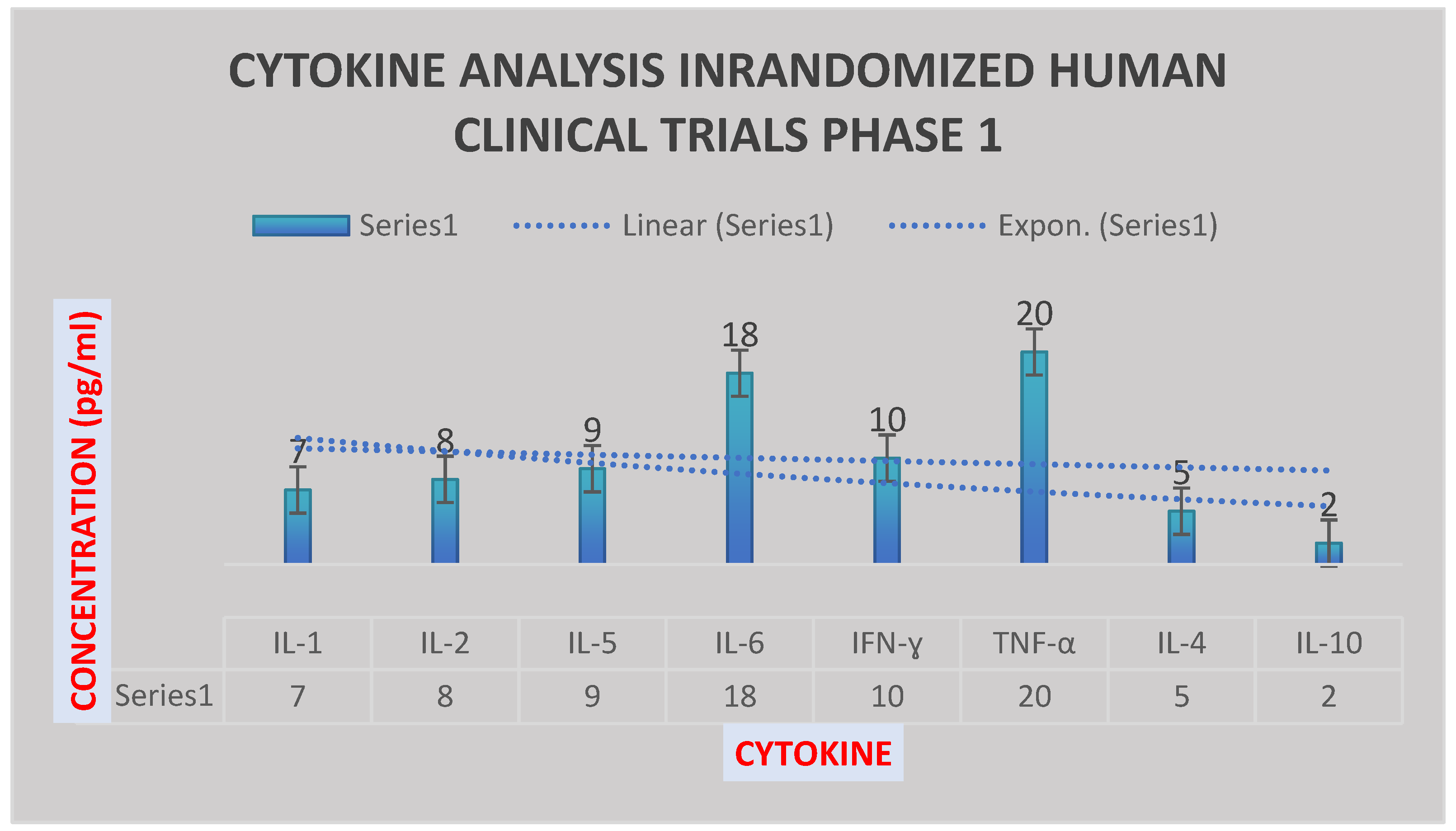

Figure 7.

It illustrates the cytokine analysis in randomized human clinical trials phase 1 after 2 months. IL-10 was reduced, while IL-6, TNF-ɑ and IFN-ɣ were increased significantly.

Figure 7.

It illustrates the cytokine analysis in randomized human clinical trials phase 1 after 2 months. IL-10 was reduced, while IL-6, TNF-ɑ and IFN-ɣ were increased significantly.

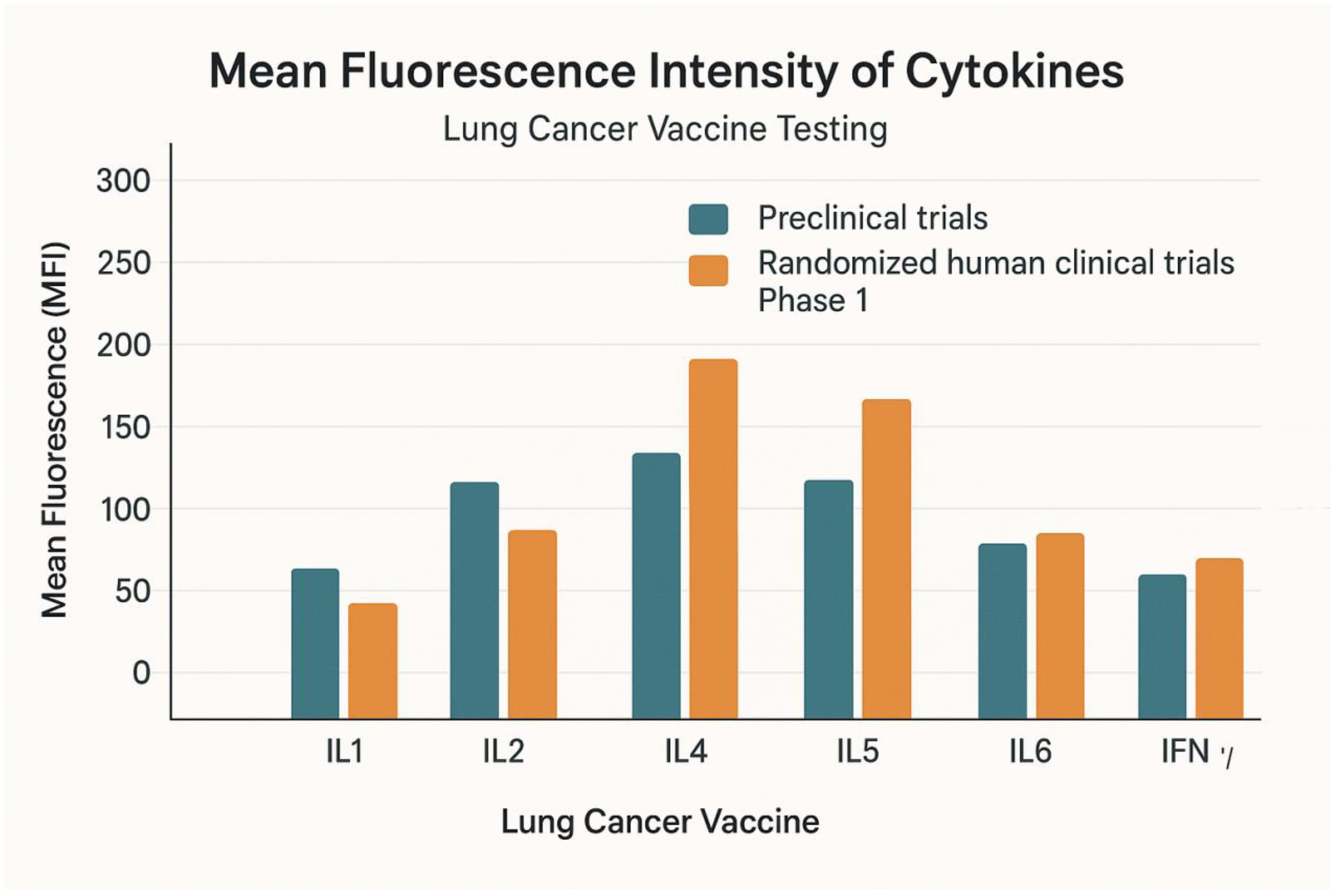

Figure 8.

It describes the mean fluorescence intensity of the cytokines during preclinical trials and randomized human clinical trials phase 1 at p≤ 0.05.

Figure 8.

It describes the mean fluorescence intensity of the cytokines during preclinical trials and randomized human clinical trials phase 1 at p≤ 0.05.

Figure 9.

It shows immune simulation prediction of the cytokine response to mutant epitopes of TMEM48, TMEM97 and KRAS protein antigens of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine. It was generated by bioinformatic C-ImmSim software.

Figure 9.

It shows immune simulation prediction of the cytokine response to mutant epitopes of TMEM48, TMEM97 and KRAS protein antigens of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine. It was generated by bioinformatic C-ImmSim software.

Figure 10.

a. It shows the mutant KRAS, TMEM48 and TMEM97 protein antigens of the lung cancer cells. The mRNA of these mutated protein antigens were used in the construction of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine. b. It demonstrates the regions of the rare mutations inside KRAS, TMEM8 and TMEM97 protein antigens of the lung cancer cells. These mutated proteins leaded to the production of powerful antibodies to them.

Figure 10.

a. It shows the mutant KRAS, TMEM48 and TMEM97 protein antigens of the lung cancer cells. The mRNA of these mutated protein antigens were used in the construction of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine. b. It demonstrates the regions of the rare mutations inside KRAS, TMEM8 and TMEM97 protein antigens of the lung cancer cells. These mutated proteins leaded to the production of powerful antibodies to them.

Figure 11.

It shows the binding of mutated KRAS protein with the inner and the outer leaflets of the lung cancer cell membrane.

Figure 11.

It shows the binding of mutated KRAS protein with the inner and the outer leaflets of the lung cancer cell membrane.

Figure 12.

Mutated TMEM48 protein antigen on the surface of the lung cancer cell membrane.

Figure 12.

Mutated TMEM48 protein antigen on the surface of the lung cancer cell membrane.

Figure 13.

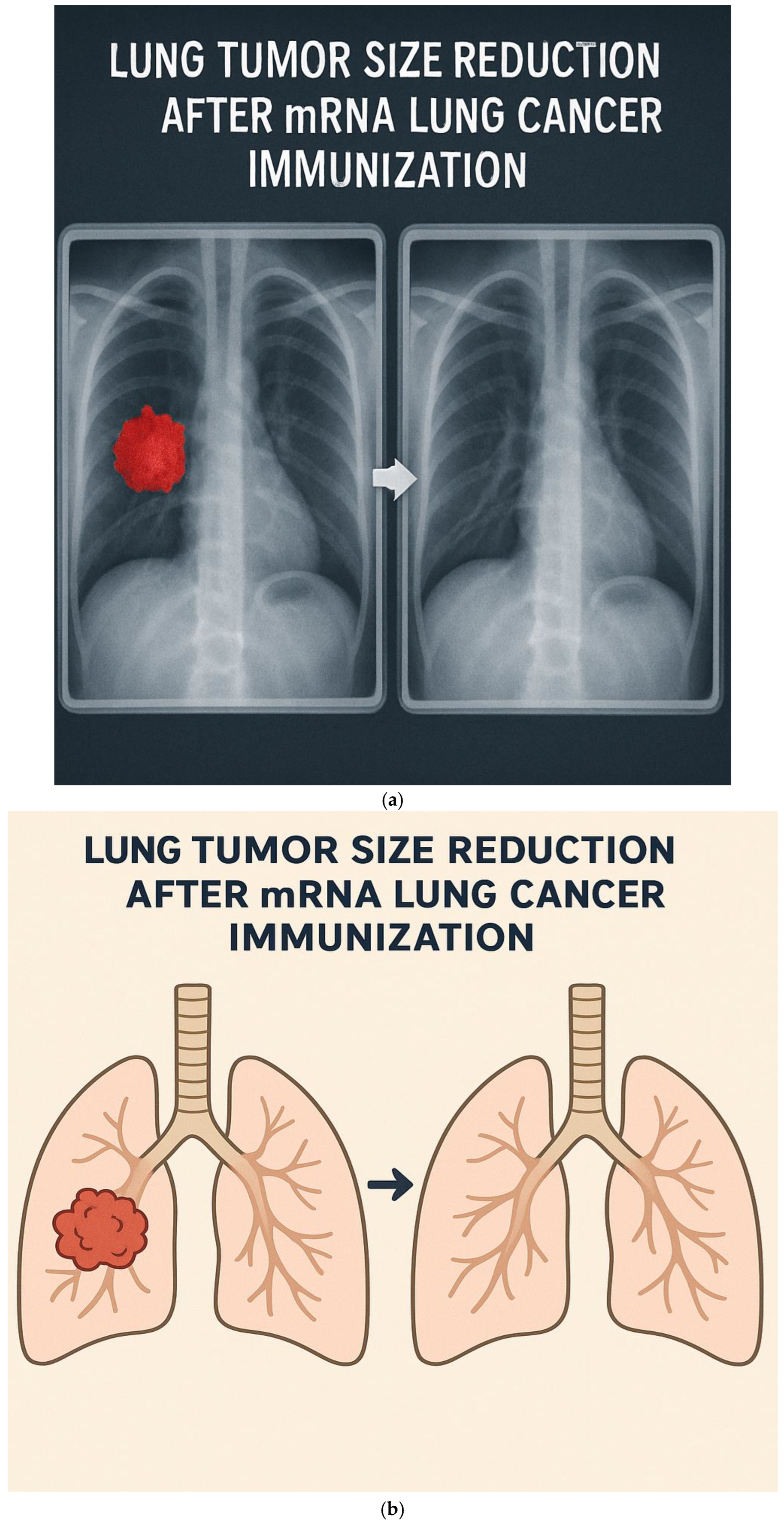

a. CT-scan of lung cancer tumor size reduction following the vaccination with LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine in randomized human clinical trials phase 1. b. Diagram represents the disappearance of lung cancer following the immunization with the therapeutic test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine.

Figure 13.

a. CT-scan of lung cancer tumor size reduction following the vaccination with LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine in randomized human clinical trials phase 1. b. Diagram represents the disappearance of lung cancer following the immunization with the therapeutic test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine.

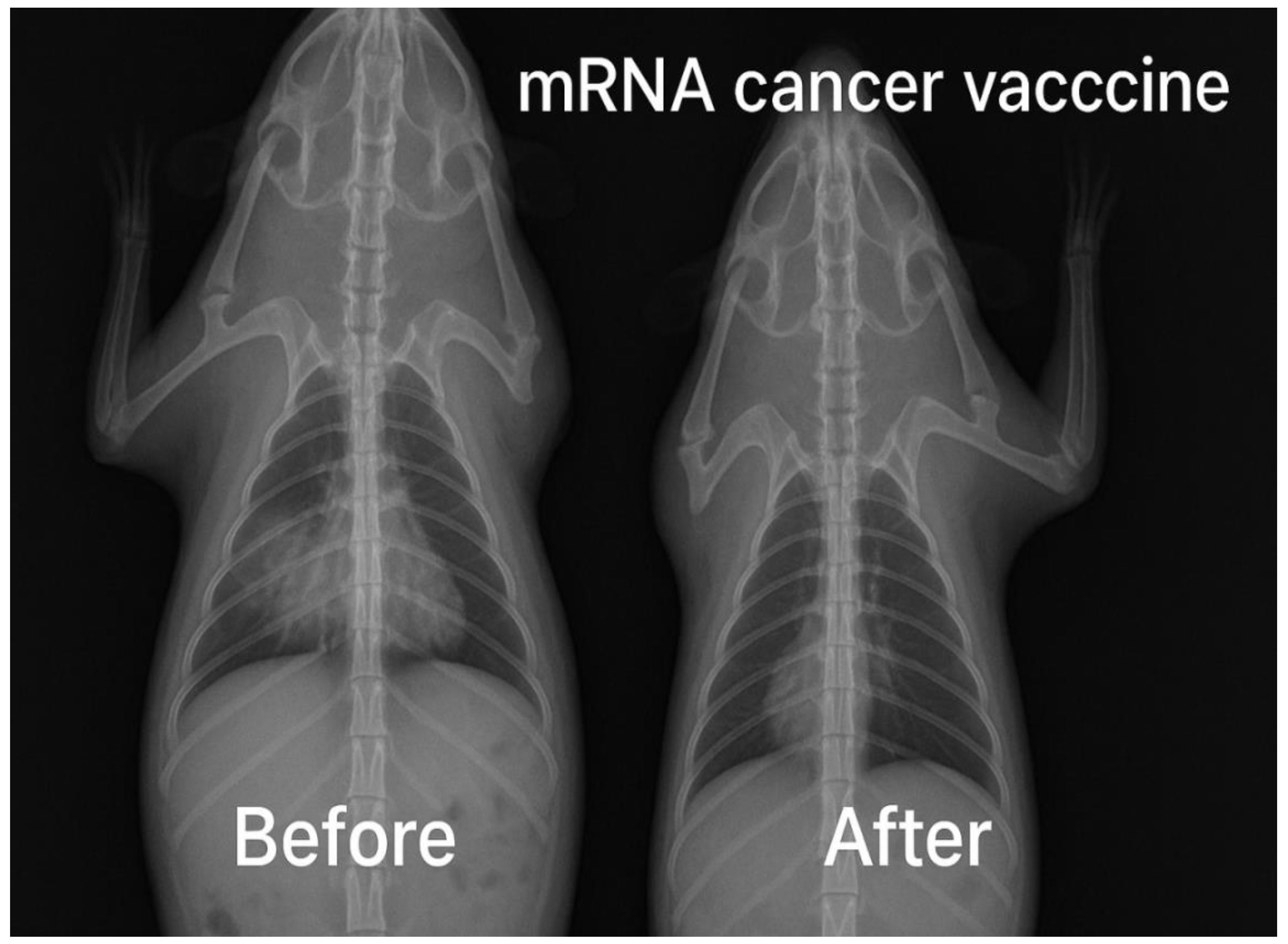

Figure 14.

It illustrates the presence of lung tumor size reduction using CT scan in preclinical trials stage.

Figure 14.

It illustrates the presence of lung tumor size reduction using CT scan in preclinical trials stage.

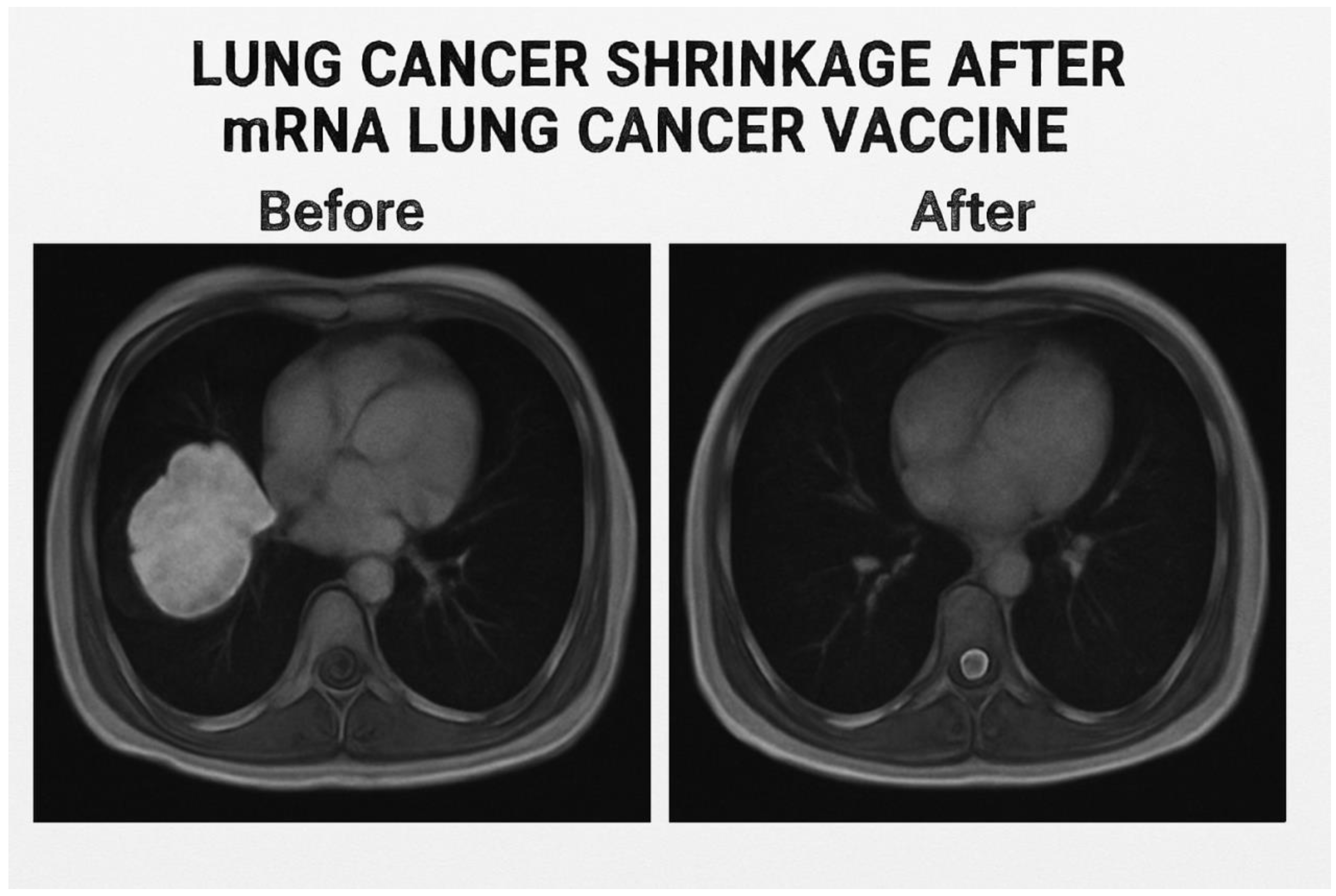

Figure 15.

It presents a magnetic resonance image of the shrinkage of the lung tumor following the immunization with the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine in randomized human clinical trials phase 1.

Figure 15.

It presents a magnetic resonance image of the shrinkage of the lung tumor following the immunization with the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine in randomized human clinical trials phase 1.

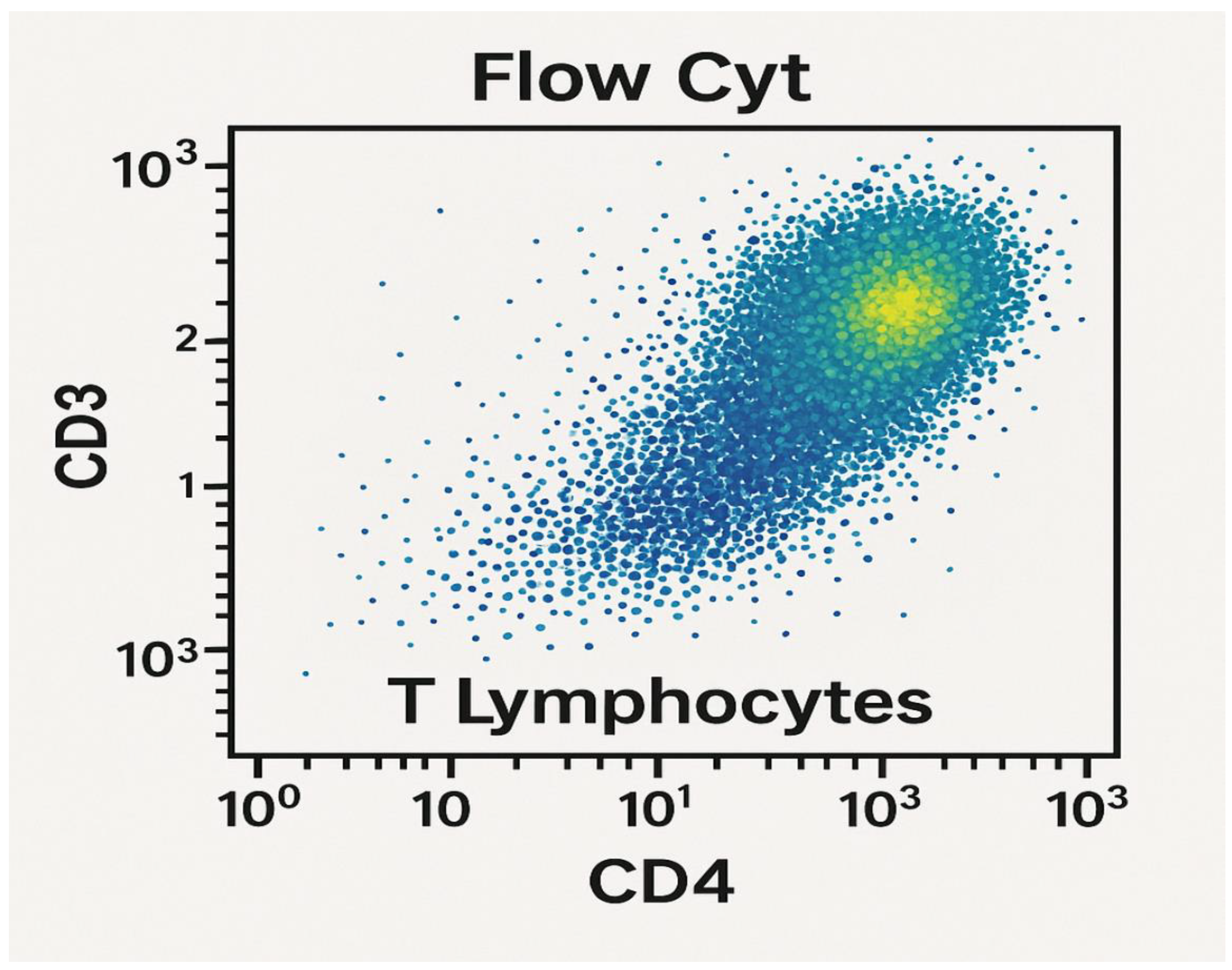

Figure 16.

It represents CD+4 T-lymphocytes count using flow cytometry in randomized human clinical trials phase 1. p≤ 0.05.

Figure 16.

It represents CD+4 T-lymphocytes count using flow cytometry in randomized human clinical trials phase 1. p≤ 0.05.

Figure 17.

Molecular docking of mutant lung cancer KRAS protein antigen.

Figure 17.

Molecular docking of mutant lung cancer KRAS protein antigen.

Figure 18.

Molecular docking of mutant lung cancer TMEM48 protein antigen.

Figure 18.

Molecular docking of mutant lung cancer TMEM48 protein antigen.

Figure 19.

Molecular docking of mutant lung cancer TMEM97 protein antigen.

Figure 19.

Molecular docking of mutant lung cancer TMEM97 protein antigen.

Figure 20.

Lipid nanoparticles containing mRNA transcripts of mutant KRAS, TMEM48 and TMEM97 protein antigens. Composition of lipid nanoparticles is illustrated in this diagram. Particle size is about 100 nm.

Figure 20.

Lipid nanoparticles containing mRNA transcripts of mutant KRAS, TMEM48 and TMEM97 protein antigens. Composition of lipid nanoparticles is illustrated in this diagram. Particle size is about 100 nm.

Figure 21.

It shows the count of CD25 T-lymphocytes and CD69 T-lymphocytes 28 days post-vaccination with the test LPNs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine using flow cytometer during randomized human clinical trials phase 1. p≤ 0.01.

Figure 21.

It shows the count of CD25 T-lymphocytes and CD69 T-lymphocytes 28 days post-vaccination with the test LPNs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine using flow cytometer during randomized human clinical trials phase 1. p≤ 0.01.

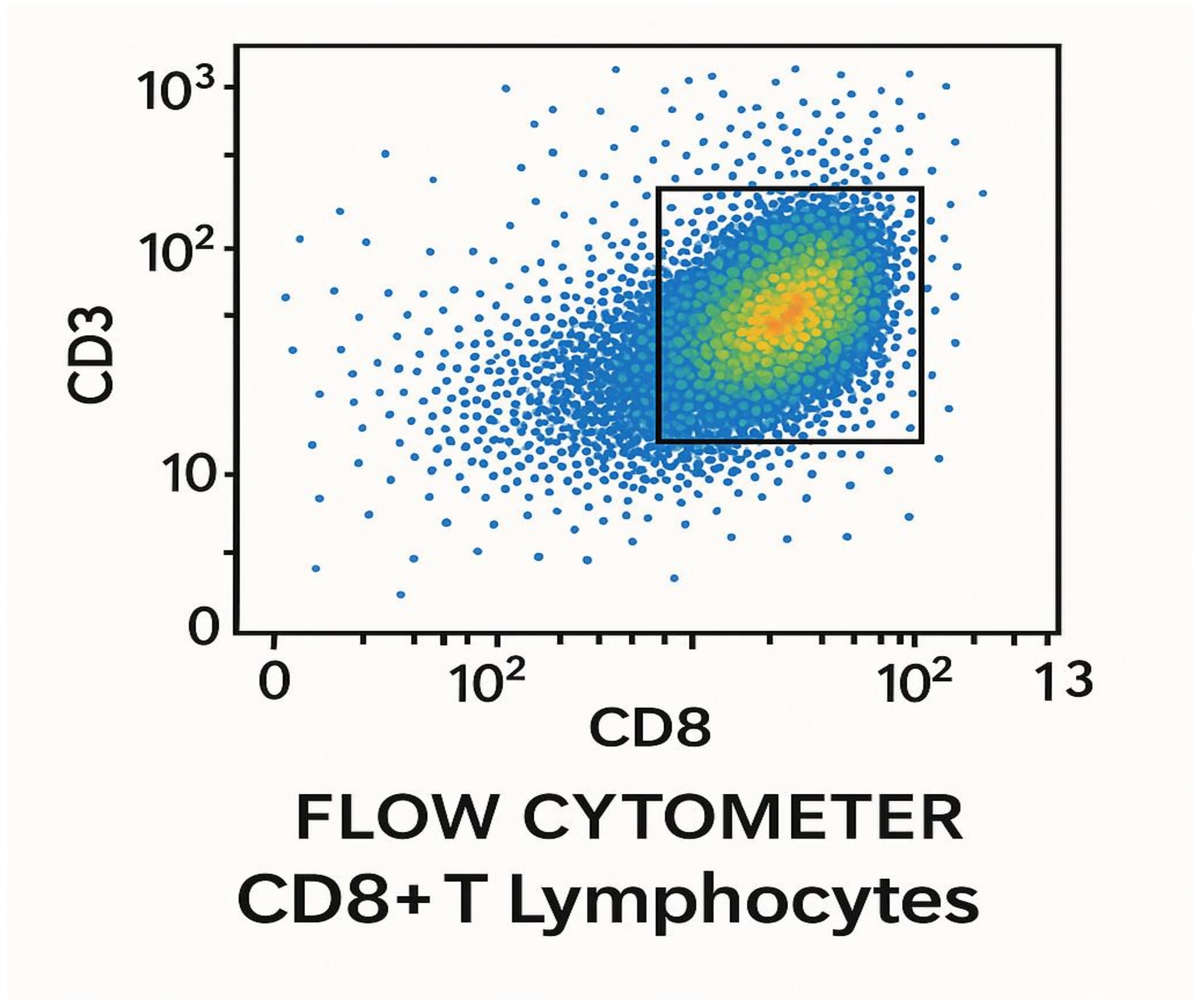

Figure 22.

Flow cytometry computation of CD+8 T lymphocytes 28 days post-vaccination with the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine in randomized human clinical trials phase 1. p≤ 0.05.

Figure 22.

Flow cytometry computation of CD+8 T lymphocytes 28 days post-vaccination with the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine in randomized human clinical trials phase 1. p≤ 0.05.

Results

The present study aimed at the determination of the efficacy of a combination immunotherapy comprising monoclonal antibodies to KRAS, TMEM48 and TMEM97 of Lung cancer cells and LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine.

Immunogenicity of the test vaccine reached 73% in preclinical trials phases, while it was 65% in randomized human clinical trials phase 1. 82% of tumor metastasis was inhibited in preclinical trials phase, while it was 76% in randomized human clinical trials phase 1.

Survival rate was found to increase by 68%, whereas it was 50% during randomized human clinical trials phase 1. The protection power of the test lung cancer immunization against the development advanced lung cancer and metastasis was detected to be 78% after the administration of the combined therapy in randomized human clinical trials phase 1, while it was 80% in animal testing stage.

The cytokines responsible for the development of the cell mediated immunity was enhanced more than the cytokines responsible for the development of the humoral immunity. TNF-α, IFN-ɣ, IL1, IL2, IL5, IL6 and IL4 were markedly increased in the present study. On the other hand IL-10 was decreased significantly.

The percentage of mice in the control group in preclinical trials phase which showed no metastasis of the lung cancer was approximately 2%, while the percentage of candidates of the negative control group of randomized human clinical trials phase 1 was nearly 1%.

During the production of monoclonal antibodies using the hybridoma technology, 1ml of the cell culture was detected to yield 963± 5 µg antibody/wells i.e. 1 ml of the cell culture yielded 10.0313±2.4 µg antibody/well. The produced neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to mutated form of the lung cancer KRAS protein was named kraslizumab.

During the manufacture of mRNA transcripts of the test antigens, In Vitro transcription technique yielded 10.00± 0.8 µg/ml of mRNA encoding mutated KRAS protein, 9.73± 0.4 µg/ml of mRNA encoding mutated TMEM97 protein and 12.06± 1.1 µg/ml of mRNA encoding mutated TMEM48 protein. UV absorption spectra of mRNA of mutated TMEM97, TMEM48 and KRAS proteins of lung cancer cells are shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, respectively. The highest degree of purifies were noticed at absorbances between 260 and 280 nm wavelengths.

Ionizable lipid nanoparticles showed spherical shape with diameter 10 nm and particle size 100 nm. Zeta potential of these particles was determined to be 31 mV and poly polydispersity index (PDI) was ascertained to be 0.07.

The immune simulation prediction of the cytokine response to mutant epitopes of TMEM48, TMEM97 and KRAS protein antigens of the test lung cancer vaccine was illustrated in

Figure 9. IL-2 and IFN-ɣ were predicted to increase the cell mediated immunity versus the lung cancer.

The docking results of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine are demonstrated in

Table 12; while the bioinformatics analysis is shown in

Table 11.

Final vaccine construct was predicted t be about 780±2 bp. GC content was 54± 3%; whereas the codon adaptation index (CAI) was 0.92± 5. Linker and adjuvant included were predicted to improve immunogenicity by 17±2 %. On the other hand I-TASSER C-score was predicted to be -0.58 and VaxiJen scores were greater than 0.6; all epitopes were non-toxic and non-allergenic. Ramachandran plot revealed that 89.2% residues were in favored regions.

The count of T lymphocytes in blood in the test group ranged from 1050-1058 cells/mm3 before the immunization with the test vaccine. Following the vaccination by 21 days, the CD+4 T helper (TH) lymphocytes were 550-552 TH1 cells/mm3 and 225-227 TH2 cells/mm3. The count of CD+8 T cytotoxic (TC) lymphocytes was 349-355 cells/mm3.

Neutralizing antibodies to the mutated TMEM48 protein of lung cancer cells using ELISA during randomized human clinical trials phase 1 were produced 14 days post-vaccination with the test vaccine LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine as shown in

Figure 5. As well as the appearance of neutralizing antibodies to mutated TMEM97 and KRAS proteins was observed after the immunization of the test vaccine. The titers of all these proteins were increased significantly after giving booster doses of the test vaccine. All neutralizing antibodies were IgM1 type.

The concentration of different cytokines during cell culturing testing of the LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine is shown in

Table 3. IFN-ɣ, IL-6 and TNF-

ɑ were the predominant cytokines. IL-10 was suppressed.

The determinations of T-lymphocytes activation and proliferation are shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, respectively. Cytotoxic (CD+8) T-lymphocytes were noticed to be predominant during the cell culturing testing stage of the LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine.

The anticancer activities of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine and the standard PD1 inhibitor during the cell culturing testing phase are demonstrated in

Table 7 and

Table 8, respectively. As the concentration of the vaccine increased the cell viability decreased. IC50 of the test vaccine and the standard PD1 inhibitor were 3.28 µg/ml and 1.61 µg/ml, respectively.

CPPs utilized in the current study were detected to augment the uptake of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine and the neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to mutant lung cancer KRAS antigen by antigen presenting cells especially dendritic cells by 17± 2.46% in preclinical trials and 13.15± 3.08%. They also intensified the immunogenicity of the combination therapy by 8± 1.61% in preclinical trials whereas it increased by 6.3 ± 2.09% in randomized human clinical trials phase 1.

Figure 13a shows a CT-scan of lung cancer tumor size reduction following the vaccination with LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine in randomized human clinical trials phase 1. As well

Figure 3b represents the disappearance of lung cancer after the administration of the test therapeutic vaccine combined with neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to mutated lung cancer KRAS protein antigen.

Figure 19 shows the molecular docking of mutant lung cancer TMEM97 protein antigen; while

Figure 18 shows molecular docking of mutant lung cancer TMEM48 protein antigen. On the other hand,

Figure 17 demonstrates molecular docking of mutant lung cancer KRAS protein antigen.

Table 2.

Preclinical trials evaluation of the count of T-lymphocytes before and after the vaccination with the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine:.

Table 2.

Preclinical trials evaluation of the count of T-lymphocytes before and after the vaccination with the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine:.

| Type of T-lymphocytes |

The mean count of the T-cells prior to vaccination (cells/mm3) |

The mean count of the T-cells following vaccination by 14 days (cells/mm3) |

P-value |

| CD+4 (TH) |

400-450 |

430-540 |

p≤ 0.05 |

| CD+8 (TC) |

100-160 |

123-187 |

p< 001 |

| Total T-lymphocytes |

500-610 |

553-727 |

p<0.05 |

Table 2 shows the assessment of the cell mediated immunity in terms of T-lymphocytes count during animal testing stage. The T- lymphocytic cells of the experimental mice spleens were counted.

ELISpot assay was used to detect the IFN-ɣ cytokine in preclinical trials phase. It was established that 58± 2 spots/106 cells (p<0.05) were determined in positive test wells, while 13± 5 spots/106 cells (p<0.01) were detected in the negative control wells.

In animal testing preclinical trials phase, 18-23% TC (CD+8) lymphocytes were activated, while 12-14% TH (CD+4) lymphocytes were activated 21 days post-vaccination of the mRNA lung cancer vaccine.

In animal testing preclinical trials phase, 45± 1% TC (CD+8) lymphocytes were proliferated, while 13± 2% TH (CD+4) lymphocytes were proliferated 21 days post-vaccination of the mRNA lung cancer vaccine.

In preclinical trials phase, the lung tumor size was decreased by the test vaccine from 2.5± 0.4 cm to 0.7± 0.2 cm, while it was decreased form 2.6± 0.8 cm to 1.2± 0.1 cm by the standard anticancer drug (10 µg/ml cisplatin).

Nivolumab, a PD-1 inhibitor, was observed to diminish the lung tumor size from 2.3± 0.6 cm to 1.1± 0.3 cm and prevented the metastasis by 60± 2%.

The test kraslizumab, a KRAS protein inhibitor, was observed to diminish the lung tumor size from 2.7± 0.2 cm to 0.9± 0.4 cm and prevented the metastasis by 52± 7%. The cure of lung cancer using this neutralizing monoclonal antibody was occurred in 7± 1% of experimental animals.

Figure 14 exposit the presence of lung tumor size reduction using CT scan in preclinical trials stage.

Neutralizing antibodies to the mutated KRAS protein of lung cancer cells using ELISA during preclinical trials phase were produced 21 days post-vaccination with the test vaccine LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine as shown in

Figure 4. As well as the appearance of neutralizing antibodies to mutated TMEM48 and TMEM97 proteins was observed after the immunization of the test vaccine. The titers of all these proteins were increased significantly after giving booster doses of the test vaccine. All neutralizing antibodies were IgM3 type.

The concentration of different cytokines determined using ELISA during animal testing of the LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine is shown in

Table 4. IFN-ɣ, IL-6 and TNF-

ɑ were the predominant cytokines. IL-10 was decreased.

Computation of anticancer activity of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine (27 µg/ml) in animal testing preclinical trials phase using LDH release assay is shown in

Table 9. As the period of time passed after vaccination with the test vaccine, the cancer cell death percentage increased gradually.

In the adult human volunteers the normal count of the T lymphocytes in blood in the test groups was 1000± 8 cells/mm3 before vaccination. After 28 days from the immunization with the test mRNA lung cancer vaccine, the count of T lymphocytes was 1046± 5 cells/mm3. The counts of CD+4 T (TH) cells were 698± 4 cells/mm3 comprising 474± 7 TH1 cells/mm3 and 224± 2 TH2 cells/mm3. The count of CD+8 (TC) cells was 348±6 cells/mm3.

Following 28 days from the administration of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine, 49± 7% TC (CD+8) lymphocytes were activated during the randomized human clinical trials phase 1, whereas 7±2% TH (CD+4) lymphocytes were activated.

After 28 days from the administration of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine, 37± 3% TC (CD+8) lymphocytes were proliferated during the randomized human clinical trials phase 1, whereas 8± 5% TH (CD+4) lymphocytes were proliferated.

After 6 months from the vaccination with the test mRNA lung cancer vaccine, the lung tumor (nodule) size was reduced from 3.8± 1.2 cm to 1.6± 0.3. On the other hand, the positive control anticancer drug cisplatin (10µg/ml) reduced the lung tumor size from 4± 0.5 cm to 1.9± 0.2 cm after 6 dosing cycles.

Nivolumab, a PD-1 inhibitor, was observed to diminish the lung tumor size from 3.9± 0.5 cm to 1.8± 0.1 cm and prevented the metastasis by 51± 3%.

The test kraslizumab (10 µg/ml), a mutated lung cancer KRAS protein inhibitor, was observed to diminish the lung tumor size from 4.7± 0.2 cm to 0.7± 0.4 cm and prevented the metastasis by 52± 1%. The cure using this neutralizing monoclonal antibody was occurred in 4± 2% of cases.

Neutralizing antibodies to the mutated TMEM97 protein of lung cancer cells using ELISA during randomized human clinical trials phase 1 were produced 28 days post-vaccination with the test vaccine LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine as shown in

Figure 6. As well as the appearance of neutralizing antibodies to mutated TMEM48 and KRAS proteins was observed after the immunization of the test vaccine. The titers of all these proteins were increased significantly after giving booster doses of the test vaccine. All neutralizing antibodies were IgM1 type.

IL-10 was reduced, while IL-6, TNF-ɑ and IFN-ɣ were increased significantly as shown in

Figure 7. IL-1, IL-5 and IL-2 were increased moderately 2 months post-vaccination with the test vaccine. IL-4 was enhanced mildly.

Estimation of anticancer activity of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine (30 µg/ml) in randomized human clinical trials phase 1 using LDH release assay is shown in

Table 10. As the time passed post-vaccination with the test vaccine, the cancer cell death percentage increased gradually.

The mean fluorescence intensity of the cytokines during preclinical trials and randomized human clinical trials phase 1 is demonstrated in

Figure 8.

Figure 10a shows the mutant KRAS, TMEM48 and TMEM97 protein antigens of the lung cancer cells. The mRNA of these mutated protein antigens were used in the construction of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine; while

Figure 10b It demonstrates the regions of the rare mutations inside KRAS, TMEM8 and TMEM97 protein antigens of the lung cancer cells. These mutated proteins leaded to the production of powerful antibodies to them.

Figure 11 shows the binding of mutated KRAS protein with the inner and the outer leaflets of the lung cancer cell membrane; whereas;

Figure 22 shows the flow cytometry computation of CD+8 T lymphocytes 28 days post-vaccination with the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine in randomized human clinical trials phase 1.

Figure 21 shows the count of CD25 T-lymphocytes and CD69 T-lymphocytes 28 days post-vaccination with the test LPNs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine using flow cytometer during randomized human clinical trials phase 1.

Figure 20 illustrates the lipid nanoparticles containing mRNA transcripts of mutant KRAS, TMEM48 and TMEM97 protein antigens. Composition of lipid nanoparticles is illustrated in this diagram. Particle size of each LNP was about 100 nm; while

Figure 12 indicates the mutated TMEM48 protein antigen on the surface of the lung cancer cell membrane.

Table 3.

Description of the concentration of different cytokines during cell culturing testing of the LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine:.

Table 3.

Description of the concentration of different cytokines during cell culturing testing of the LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine:.

| Cytokine |

Concentration of test cytokine (pg/ml) 14 days post-vaccination |

Concentration of cytokine of the control (pg/ml) 14 days post-vaccination |

p-value |

| IL-1 |

3 |

2 |

p≤0.05 |

| IL-2 |

1.5 |

0.4 |

p≤ 0.001 |

| IL-4 |

1.8 |

0.7 |

p≤ 0.01 |

| IL-5 |

0.9 |

0.6 |

p≤ 0.01 |

| IL-10 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

p≤ 0.05 |

| TNF-ɑ |

3.6 |

1.8 |

p≤ 0.002 |

| IFN-ɣ |

4.1 |

2.9 |

p≤ 0.01 |

| IL-6 |

5.3 |

3.1 |

p≤ 0.05 |

Table 4.

Determination of the concentration of different cytokines using ELISA during animal testing of the LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine:.

Table 4.

Determination of the concentration of different cytokines using ELISA during animal testing of the LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine:.

| Cytokine |

Concentration of test cytokine (pg/ml) 21 days post-vaccination |

Concentration of cytokine of the control (pg/ml) 21 days post-vaccination |

p-value |

| IL-1 |

4 |

1 |

p≤0.01 |

| IL-2 |

2 |

0.5 |

p≤ 0.05 |

| IL-4 |

1.7 |

0.6 |

p≤ 0.05 |

| IL-5 |

0.8 |

0.4 |

p≤ 0.01 |

| IL-10 |

0.2 |

0.7 |

p≤ 0.01 |

| TNF-ɑ |

3.1 |

2 |

p≤ 0.002 |

| IFN-ɣ |

3.9 |

1.3 |

p≤ 0.05 |

| IL-6 |

5.5 |

2.1 |

p≤ 0.01 |

Table 5.

It states the T-cell activation during cell culturing testing of LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine:.

Table 5.

It states the T-cell activation during cell culturing testing of LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine:.

| Type of T-lymphocytes |

Percentage of activation (%) |

p-value |

| CD+8 TC |

17-23% (KRAS-specific), 21-25% (TMEM48-specific), 27-31% (TMEM97-specific) |

p≤ 0.05 |

| CD+4 TH1 |

13-15% |

p≤ 0.05 |

| CD+4 TH2 |

6-7% |

p≤ 0.01 |

| Tumor infiltirating T-cells |

47-49% |

p≤ 0.02 |

Table 6.

It indicates the T-lymphocytes proliferation during cell culturing testing of LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine:.

Table 6.

It indicates the T-lymphocytes proliferation during cell culturing testing of LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine:.

| Type of T-cells |

Percentage of proliferation (%) |

p-value |

| CD+4 TH |

29% (14% CD+4 TH1, 15% CD+4 TH2) |

p≤ 0.05 |

| CD+8 TC |

51-53 |

p≤ 0.01 |

| |

|

|

Table 7.

It shows the anticancer activity of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine during the cell culturing testing phase:.

Table 7.

It shows the anticancer activity of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine during the cell culturing testing phase:.

| Mean concentration of test vaccine-anticancer agent (µg/ml) |

Absorbance (A490-A630) |

Percentage of the cell viability (%) |

p-value |

| 0.001 |

0.1 |

98 |

p≤ 0.01 |

| 0.01 |

0.2 |

81 |

p≤ 0.05 |

| 1 |

0.5 |

59 |

p≤ 0.01 |

| 10 |

0.8 |

27 |

p≤ 0.05 |

| 100 |

0.9 |

4 |

p≤ 0.03 |

Table 8.

It shows anticancer activity of the standard PD1 inhibitor during the cell culturing testing phase using XTT assay:.

Table 8.

It shows anticancer activity of the standard PD1 inhibitor during the cell culturing testing phase using XTT assay:.

|

Mean concentration of standard PD1 agent (µg/ml)

|

Absorbance (A490-A630) |

Percentage of the cell viability (%) |

p-value |

| 25 |

0.2 |

78 |

p≤ 0.01 |

| 50 |

0.6 |

49 |

p≤ 0.05 |

| 75 |

0.9 |

34 |

p≤ 0.01 |

| 100 |

1 |

19 |

p≤ 0.05 |

| 125 |

1.4 |

5 |

p≤ 0.03 |

Table 9.

Estimation of anticancer activity of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine (27µg/ml) in preclinical trials stage using LDH release assay:.

Table 9.

Estimation of anticancer activity of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine (27µg/ml) in preclinical trials stage using LDH release assay:.

| Time (days) |

Percentage of cancer cell death (%) |

p-value |

| 3 |

5 |

p≤ 0.05 |

| 7 |

30 |

p≤ 0.05 |

| 10 |

52 |

p≤ 0.01 |

| 14 |

81 |

p≤ 0.05 |

| 21 |

93 |

p≤ 0.01 |

Table 10.

Estimation of anticancer activity of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine (30 µg/ml) in randomized human clinical trials phase 1 using LDH release assay:.

Table 10.

Estimation of anticancer activity of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine (30 µg/ml) in randomized human clinical trials phase 1 using LDH release assay:.

| Time (days) |

Percentage of cancer cell death (%) |

p-value |

| 2 |

3 |

p≤ 0.01 |

| 10 |

21 |

p≤ 0.01 |

| 21 |

45 |

p≤ 0.05 |

| 28 |

72 |

p≤ 0.05 |

| 60 |

83 |

p≤ 0.01 |

Table 11.

It demonstrates bioinformatics analysis of predicted epitopes of the mutant protein antigens included in the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine:.

Table 11.

It demonstrates bioinformatics analysis of predicted epitopes of the mutant protein antigens included in the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine:.

| Gene |

Epitope |

Mutation |

HLA Allele |

Affinity (nM) |

VaxiJen |

Toxicity |

Allergenicity |

| KRAS |

VVVGACGVGK |

G12C |

HLA-A*02:01 |

35.4 |

0.78 |

Non-toxic |

Non-allergen |

| TMEM48 |

LPRCFLKRI |

R133C |

HLA-A*02:01 |

42.6 |

0.74 |

Non-toxic |

Non-allergen |

| TMEM97 |

YLPPLRALV |

P62L |

HLA-A*02:01 |

29.8 |

0.81 |

Non-toxic |

Non-allergen |

Table 12.

It indicates to the docking results of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine:.

Table 12.

It indicates to the docking results of the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine:.

| Epitope |

Receptor |

Binding Energy (kcal/mol) |

H-Bonds |

Key Interactions |

| VVVGACGVGK |

HLA-A*02:01 |

-9.2 |

7 |

Tyr159, Ser95 |

| LPRCFLKRI |

HLA-A*02:01 |

-8.8 |

5 |

Asp77, Glu63 |

| YLPPLRALV |

HLA-A*02:01 |

-9.5 |

6 |

Lys66, Gln155 |

Toxicity found in the present study in randomized clinical trials phase 1 included mild pain at the injection site of the vaccine with little redness and mild fever relieved by ibuprofen administration.

Figure 16 represents CD+4 T-lymphocytes count using flow cytometry in randomized human clinical trials phase 1. On the other side,

Figure 15 presents a magnetic resonance image of the shrinkage of the lung tumor following the immunization with the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine in randomized human clinical trials phase 1.

Discussion

Lung cancer remains a leading cause of cancer-related mortality globally. Personalized immunotherapies, such as mRNA-based vaccines, and performed neutralizing antibodies to selected coherent epitopes of mutant antigens (KRAS, TMEM48, and TMEM97) offered promise due to their safety and adaptability. The present study aimed at designating a multi-epitope mRNA vaccine targeting lung cancer antigens using comprehensive bioinformatics and molecular docking approach.

The designed mRNA lung cancer vaccine construct demonstrated strong immunogenicity, favorable high MHC binding, and stable immune receptor interactions in silico.

In the present study, the immunological effects of a lipid nanoparticle (LNP)-formulated mRNA vaccine targeting lung cancer-associated antigens were evaluated. The in vitro results demonstrated a significant stimulation of both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses, with the latter being more dominant. This skewing toward cell-mediated immunity was consistent with the mechanistic advantage of mRNA vaccines in promoting antigen presentation through MHC class I pathways, thereby enhancing cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activation (Sahin et al., 2017).[

19]

Cytokine profiling revealed increased expression of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-6 after vaccine administration. TNF-α and IFN-γ were hallmark cytokines associated with Th1 immune responses and effective tumor immunosurveillance. Their elevation suggested an activation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells capable of recognizing and eliminating tumor cells (Kranz et al., 2016).[

20] IL-2 supported the proliferation and survival of activated T cells, further sustaining the anti-tumor response (Haabeth et al., 2021).[

21] Although IL-6 can play a dual role in cancer, its transient increase in the early phase of immune activation likely contributed to dendritic cell maturation and T-cell differentiation (Tanaka et al., 2014).[

22]

These findings were in agreement with previous studies on LNP-mRNA cancer vaccines. For example, Kranz et al. (2016) showed that systemic delivery of LNP-encapsulated mRNA encoding tumor antigens led to strong T-cell responses and tumor control in mouse models.[

20]

Similarly, Sahin et al. (2017) reported that individualized mRNA neoantigen vaccines induced both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in melanoma patients.[

19]

More recently, Hewitt et al. (2023) demonstrated that LNP-mRNA vaccines targeting KRAS mutations led to increased infiltration of CD8+ T cells in lung tumors, corroborating the dominance of cell-mediated immunity observed in our study.[

23]

Compared to traditional protein or peptide vaccines, which often relied on adjuvants to stimulate immunity and tended to favor antibody production, mRNA vaccines offered the advantage of endogenous antigen production and presentation. This supported the development of cytotoxic responses, which were crucial for eradicating cancer cells. Furthermore, LNPs enhance the stability and delivery efficiency of mRNA, ensuring its uptake by antigen-presenting cells, especially the dendritic cells, and promoting immune activation (Pardi et al., 2018).[

24]

The present study presented a novel mRNA-based lung cancer vaccine targeting the neoantigens mutant KRAS, TMEM48, and TMEM97, all of which are overexpressed across both non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). The present study demonstrated that this strategy elicited a potent antitumor immune response, both in preclinical murine models and in a Phase I clinical trial, particularly when combined with neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to mutant KRAS and PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade.

In syngeneic mouse models, vaccine-induced immunogenicity reached 73%, resulting in 82% tumor inhibition, a 68% increase in survival, and 78% protection against metastasis.

Translating to human subjects, the Phase I trial showed consistent immunogenicity (65%), tumor suppression (76%), and survival benefit (50% increase), underscoring the vaccine's translatability and biological robustness. These effects were observed in both NSCLC and SCLC cohorts, supporting the broad utility of the selected neoantigens across lung cancer subtypes.

The mRNA vaccine induced a strong Th1-skewed immune response, evidenced by marked increases in TNF-alpha, IFN-ɣ, IL-1, IL-2, IL-5, and IL-6. The predominance of cytokines associated with cell-mediated immunity aligned with the intended design of the vaccine to stimulate cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses rather than humoral activation. These findings were consistent with previous reports demonstrating the superiority of Th1-type responses in mediating durable tumor control in solid malignancies.

A key feature of this strategy was the inclusion of mutant KRAS, a historically undruggable target, as both an mRNA antigen and a site for monoclonal antibody engagement. The use of KRAS-targeted neutralizing antibodies, administered at anatomically distinct sites from the mRNA vaccine, yielded synergistic effects without observable toxicity. This dual approach was further potentiated by PD-1 the blockade, which countered T cell exhaustion and enhanced effector function-mirroring clinical successes seen in checkpoint therapy for advanced NSCLC.

Compared to prior mRNA vaccine studies in oncology-such as the neoantigen vaccine trials in melanoma (Sahin et al., Nature, 2017)[

19] and glioblastoma (Keskin et al., Nature, 2019)[

25]-The present study strategy demonstrated greater tumor inhibition (82% vs. ~60%), enhanced anti-metastatic efficacy, and more favorable cytokine induction, likely due to the combination immunotherapy strategy and refined antigen selection. These results positioned the test LNPs-mRNA lung cancer vaccine design as a next-generation approach with clear immunological and therapeutic advantages.

CPPs used in the present study were noticed, in both preclinical trials and randomized human clinical trials, to increase significantly the uptake of the test vaccine and the neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to mutant lung cancer KRAS by antigen-presenting cells, especially dendritic cells and also enhanced the immunogenicity of the combination therapy.

This study had limitations. The Phase I trial was not powered for long-term efficacy endpoints such as progression-free or overall survival, and follow-up remains ongoing. Further, while antigen selection was based on prevalence and tumor-specific expression, personalized neoantigen profiling might offer additional precision. Nonetheless, the inclusion of conserved and high-frequency targets such as mutant KRAS supported scalability and applicability across patient populations.

In summary, The present study results validated the use of a multi-epitope mRNA vaccine targeting lung cancer neoantigens and demonstrated that combination with monoclonal antibodies and checkpoint blockade significantly augmented antitumor immunity. The consistency between preclinical and early clinical findings provided a strong rationale for advancement to Phase II trials, intending to optimize dose, delivery, and integration into standard-of-care treatment regimens for lung cancer.