1. Introduction

Recently, researchers and industrial scientists have focused the attention on wood modification in order to reduce its sensitivity to moisture and improve its properties. Therefore, different techniques, based on thermal, chemical resin impregnation procedures, have been investigated and developed in order to modify and enhance the wood mechanical characteristics. The first applications of densified wood date back to

1930s, when metal materials of USA and Germany military army were replaced by densified wood. Then, different approaches, based on compression by temperature aid, have been investigated to produce densified wood. In some studies, it has been observed that the effective improvement of wood physical and mechanical properties can be attained by thermal treatments, impregnation or densification processes. Among these processes, the compression along the transverse direction [

1,

2,

3] provide the wood densification and the improvement of its mechanical performances [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Before compression, the wood can be heated at high temperatures [

10], softened with hot steam [

11], chemical treated [

12] or impregnated with resins [

13,

14].

Wood consists mainly of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin. Cellulose is in a very rigid packing crystalline form, able to form hydrogen bonds responsible for wood strength. Lignin provides a protective cover around the cellulose structure and is strongly interconnected. It binds cellulose fibers and ensures stiffness to the cell walls. Hemicellulose is strongly bound to cellulose fibrils, it has an amorphous structure and hydrophilic characteristics. Due to its hydrophilic nature, the water molecules can absorb it reducing its dimensional stability.

Song et al. [

15] developed a wood densification method, based on a chemical bath in a water solution of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and sodium sulfite (Na

2SO

3) that enables the removal of a part of cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and other carbohydrates. Hemicellulose is degraded in acid conditions, this condition condenses the lignin and decreases its removal. Delignification treatments are carried out by means of ethanol, alkali, and ionic liquids sodium hydroxide (NaOH) is commonly used in alkali treatment which helps to solubilize and extract lignin by influencing the acetyl group in hemicellulose and bonds of lignin–carbohydrate ester. After this treatment, wood is then compressed and reduces its volume up to 80% and significantly improves its mechanical properties compared to non-treated wood. The resulting product is characterized by high values of strength and resistance to punctures that depend not only on the densification, but also on the formation of new hydrogen bonds due to the increased order and compression of cellulose nanofibers. In addition, a significant reduction in elastic recovery is observed due to the content reduction of hemicellulose and lignin, affecting the shape stabilization and quasi-elastic recovery respectively. The density of the wood is an index of its mechanical performance: lowering the number of defects enhances its density and mechanical behavior. The aggressive effects of acids formed through the demolition of wood carbohydrates during the alkali treatment involve high chemical recovery costs. The most promising methods are based on the combined use of heat, moisture, and mechanical action the Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical treatments [

16,

17,

18,

19]. These procedures can improve the intrinsic properties of wood, without changing its characteristics, and improve the poor mechanical properties of low-density wood. The Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical treatment, in fact, adopts a mechanical compression perpendicular to the grain and densify the wood. Process parameters, affecting the properties of densified material, are the applied stress level, process temperature and the environment steam conditions during densification [

20,

21]. In addition, in the densified wood a through thickness density profile can be evidenced that varies with the degree of densification and depends on the temperature and moisture gradients generated by the densification process, on the application time of the compression stress and, hence, on the glass transition of the wood walls [

22,

23]. In general, it has been observed that the density increase affects the strength and stiffness of the wood material [

24,

25]. Moreover, among the different thermal treatments, the most promising and interesting method is the hydrothermal modification [

26,

27,

28]. It works in presence of steam or liquid water under pressure or vacuum at various temperature levels and reduces the equilibrium moisture content of treated wood samples, by providing consequently the improvement of dimensional stability. The moisture reduction is determined by heat action on the reduction hydroxyl groups [

29]. The application of this method makes more hydrophobic the wood that absorbs less water and less susceptible to fungal growth [

30,

31,

32]. Some Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical processes have a high material yield and consume little energy, and thus are economically advantageous compared to the processing of other materials [

16]. However, the technical and environmental performance of these processed wood products is not always competitive and have to be improved.

Oak is a hardwood used for thousands of years. It can be modified by chemical, physical or biological treatments that change the chemical composition and enable the realization of a new material.

In this study, a new hydrothermal method, based on the treatment of oak wood slices in a Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave, is proposed. In particular, the treatment, performed in a water/ethanol solution at a temperature of 195°C for 80 minutes, involves the pressing of wood pieces by heat application, inducing to the total collapse of wood cell walls and the high alignment of cellulose nanofibres. The morphological, physical, mechanical and chemical properties of treated wood by hydrothermal method have been investigated, analyzed and compared with the respective characteristics of wood treated by more conventional alkali modification method.

2. Materials and Methods

Oak (Quercus) wood slices, from Naples Gardens (Italy) of size 10×10 cm with a thickness of 1 cm, were used in this study. Oak samples were cut and stored at an average moisture content of about 70%. The wood growth rings were uniformly oriented.

Sodium sulfite (Na2SO3), Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), Ethanol 99% v/v, and other chemical reagents, purchased from Merck Life Science (Milano, Italy), were used as received.

2.1. Densification of Wood

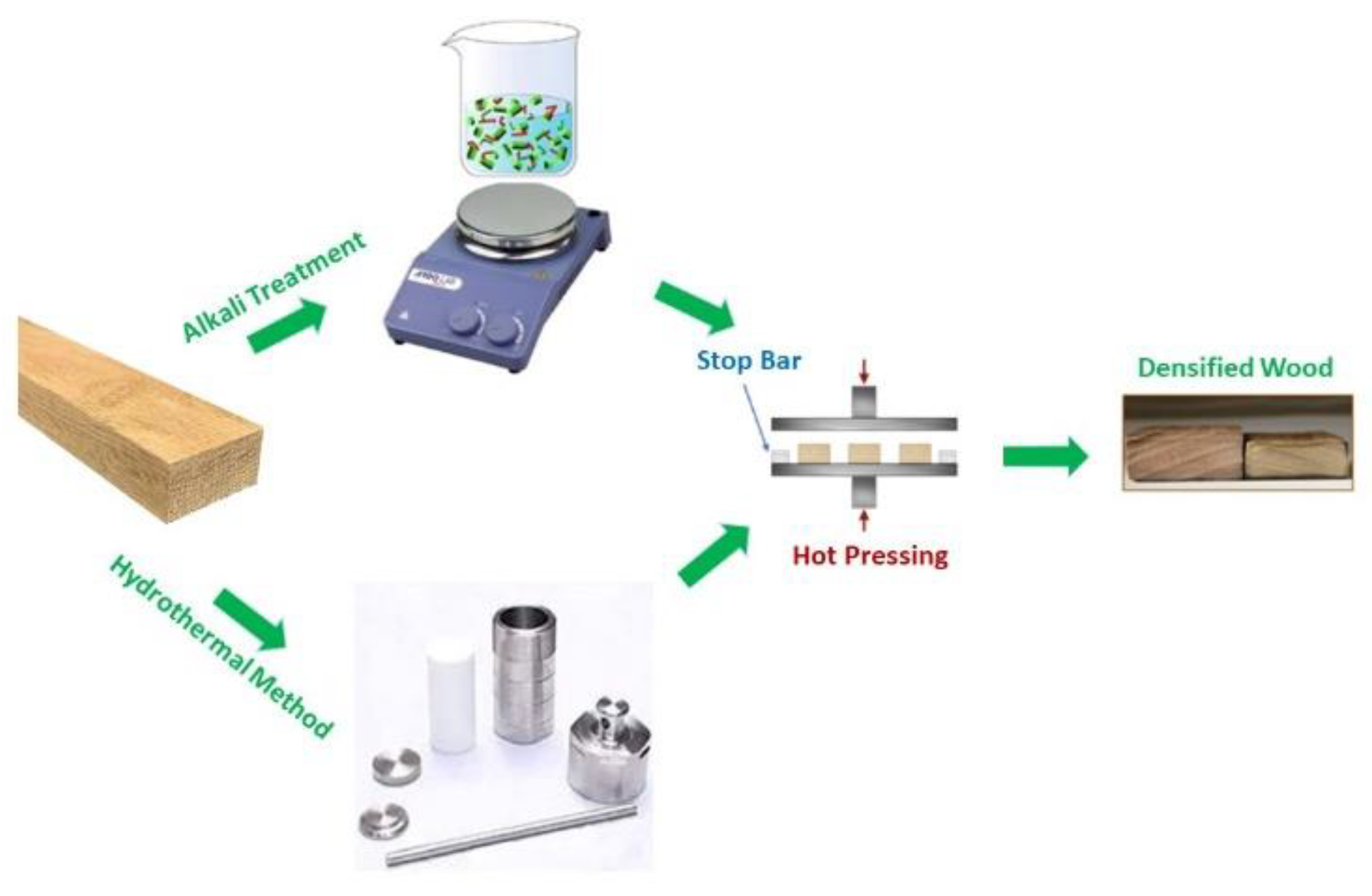

Wood samples treated by traditional alkali processes were compared with similar samples subjected to the green hydrothermal method in terms of structural effects suffered by the cell walls (see

Figure 1).

In this study, the alkali process has been performed by firstly immersing oak wood blocks (sample size 10 × 10 cm, and 5 mm of mean thickness) in a boiling aqueous solution consisting of 2.5 M NaOH and 0.4 M Na

2SO

3 for 7 hours and then in boiling deionized water repeatedly to remove chemicals [

15]. The ratio wood slice/liquid volume was 10x10 cm/ 700 mL of alkali solution. The obtained wood blocks were pressed at 100 °C at about 5 MPa for about 24 hours (see

Figure 1).

Unlike traditional wood hydrothermal methods, in this research the treatment was performed in presence of water in a sealed closed Teflon-lined autoclave, where the temperature and pressure were fixed and determined the thermodynamic by affecting the degradation of all components of wood. The temperature was selected above 160°C, in order to promote the drastic decomposition of wood tissue. The fixed pressure eased to push the liquid into the wood cell gaps or through the grooves, inducing cracks in the intercellular layer. No hazardous chemicals were used, but only water as the treatment medium and ethanol to catalyze the chemical reaction of extraction of lignin, converting hydrophilic (-OH–) groups into more hydrophobic groups and decreasing the equilibrium moisture content. It is known that high quantities of the hemicelluloses can be easily extracted at water temperatures of about 180-200 °C. Therefore, oak wood blocks (sample dimension 10x5 cm) were first immersed in a water/ethanol solution 10% v/v and then transferred to a Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave with an external height of 17 cm and diameter of 7 cm, having the Teflon chamber with height of 8 cm and diameter of 4.5 cm, which was sealed and maintained at 195℃ for 80 min. The ratio wood slice/liquid volume was 10x5 cm/ 40 mL of water-ethanol. The use of the closed Teflon autoclave settled the thermodynamic conditions of the reaction that advanced faster and deeply as extraction of lignin occurred from the external layers. In this way, a reduction in chemical reaction time was attained and, only wood pulp was formed as sub-waste’’

Finally, also for this procedure, the wood blocks were repeatedly immersed in deionized water to remove chemicals and residues. The densified wood blocks were, then, obtained after compression at 100 °C under a pressure of about 5 MPa for about 24h (see

Figure 1).

To evaluate both structural/morphological properties and thermodynamic/functional properties of oakwood before and after densification treatments several experimental techniques have been used. In each case, at least 5 measurements were performed to ensure the reproducibility of the results.

The content of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin before and after the treatment was determined. In particular, the content of Cellulose was evaluated by means of the Kürschner-Hoffer method [

35], the Lignin by ASTM D 1106 – 96 and Seifert´s cellulose by means of Acetylacetone method [

36]. Based on the Kürschner-Hoffer method wood-extracted sawdust (1g) is boiled with a mixture of concentrated HNO

3 and 95% ethyl alcohol (1:4) in a flask under reflux for 1 h. After filtering, washing (ethanol, HNO

3 and hot water) and drying in an oven at a temperature of 105 °C to constant weight, the amount of cellulose was determined gravimetrically. The procedure according to ASTM D 1106-96 is based on two-stage treatment with sulfuric acid. The brown lignin precipitate settled, filtered through a weighed glass filter, and thoroughly washed with hot water followed by drying in an oven at a temperature of 105 °C to constant weight, and the amount of lignin was determined gravimetrically. About the Acetylacetone method: 1 g of extracted sawdust was heated in a boiling water bath for 30 min in a mixture of acetylacetone, dioxane and HCl (37% w/w). Cooling was followed by the addition of methanol, hot water and dioxane. Subsequently, the sample was dried to constant weight in an oven at a temperature of 105 °C and the amount of Seifert cellulose was determined gravimetrically. The content of hemicelluloses was measured as the difference between the holocellulose and cellulose content.

Scanning Electron Microscopy and X-Ray Microanalysis (SEM-EDX)

The morphology of oak wood was investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a field emission instrument Quanta 200 FEG. Sample was covered with a layer of gold/palladium alloy in a high resolution metallizer Emitech K575X. X-Ray microanalysis was performed by EDX Inca Oxford 250 instrument. The cut directions were the same for all samples.

Thermogravimetri Analysis

The specimens were scanned by a TA Instruments Q500 TGA (TA Instruments, New Castle, Delaware, USA) under air atmosphere conditions at heating rate of 10°C/min from environmental temperature to 800 °C.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry

The specimens were double scanned by a TA Instruments TRIOS Q5000 DSC (TA Instruments, New Castle, Delaware, USA) under air atmosphere at heating rate of 10°C/min from -50°C to 250°C.

Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)- Three Point Bending

The Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer (DMA) instrument is used to detect the viscoelastic properties by applying either a small oscillating strain to the sample and measuring the resulting stress or a periodic stress and the resulting strain. Samples were analyzed by a TA Instruments 2980 Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer (TA Instruments, New Castle, Delaware, USA). Experimental measurements were carried out on five different specimens.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Alkali and Hydrothermal Modification on Oak Wood Properties Morphology

After the alkali and hydrothermal process, the degradation of hemicellulose caused the production of chromophores and the color change of oak wood samples due to chemicals and high temperature. In particular, as the treatment temperature and time increase, the treated wood was more dark [

33].

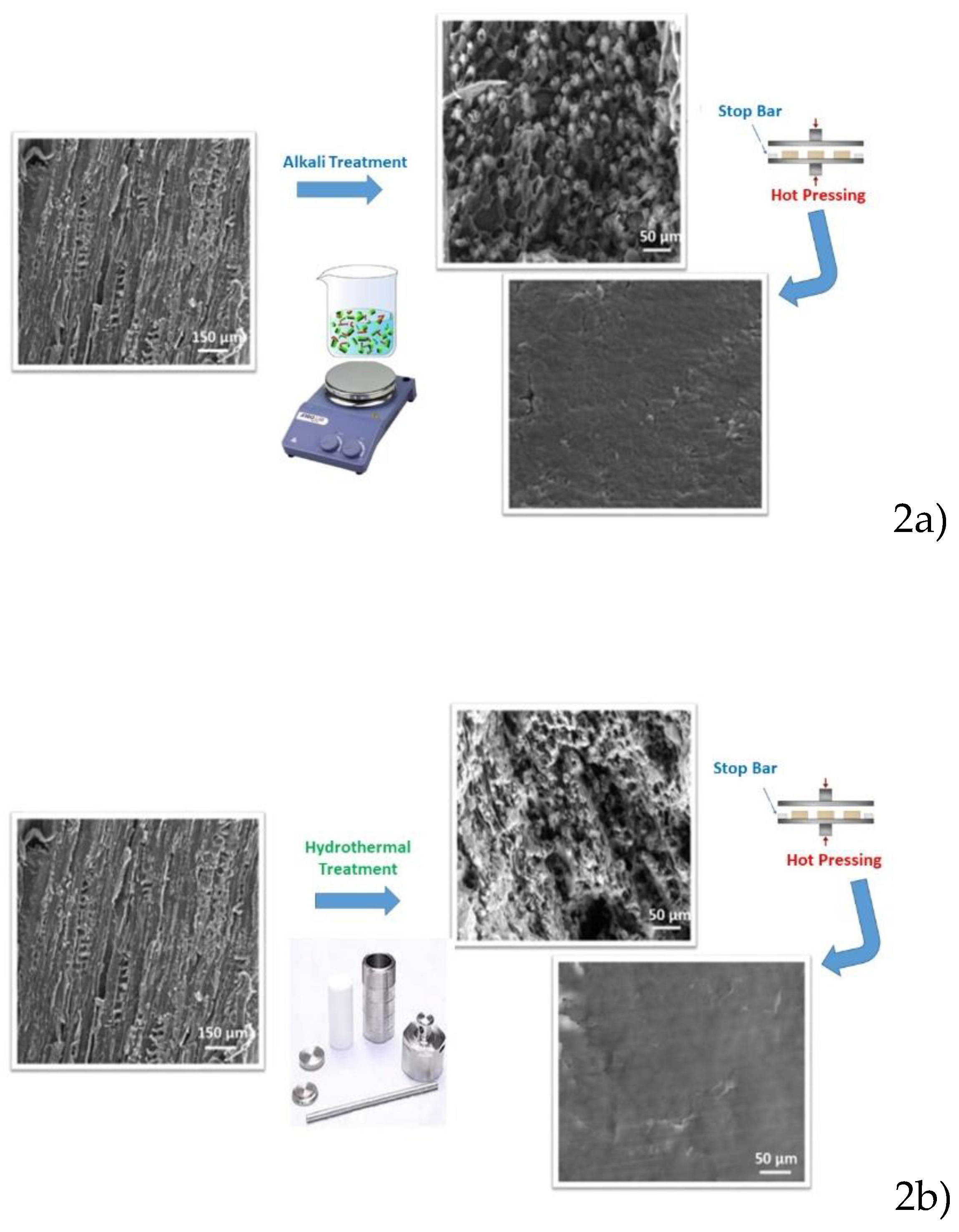

Figure 2 shows structural modifications that occur during densification modification both by means of alkali and hydrothermal process.

Clearly, the wood becomes more porous and less rigid after the chemical treatment. Oak wood treated in diluted acid aqueous solution showed the greatest damage, where both the middle lamella layers and the secondary cell wall were significantly destroyed. Upon hot-pressing at 100°C along the transverse direction to the wood growth, the porous wood cell walls collapse entirely, realizing a densified wood with a thickness reduction to about 23%.

Conversely, for samples subjected to hydrothermal treatment, a porous structure of the wood with small pores is noted, the cell walls are not destroyed and cracks are formed in the central lamellar layers. Hot pressing causes the porous wood cells to collapse, the thickened piece of wood shrinks in thickness to about 67%, compared to alkali treatment.

3.2. Chemical Properties

As already mentioned the oak wood cell walls consist of cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and small amounts of extractives, proteins, and inorganic components. Hemicellulose degrades both during alkali and hydrothermal treatment, through deacetylation, depolymerization, and dehydration, while cellulose shows increased crystallinity. Lignin during hydrothermal and alkali processes is subjected to some structural changes due to polycondensation reactions and crosslinking with cell walls. Most of the extractives evaporate or degrade, particularly those volatile ones, but new compounds can also be generated [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. All these changes undergone by the basic constituents of wood affect its ultimate properties.

Table 1 reports the % weight content of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin for untreated and treated wood.

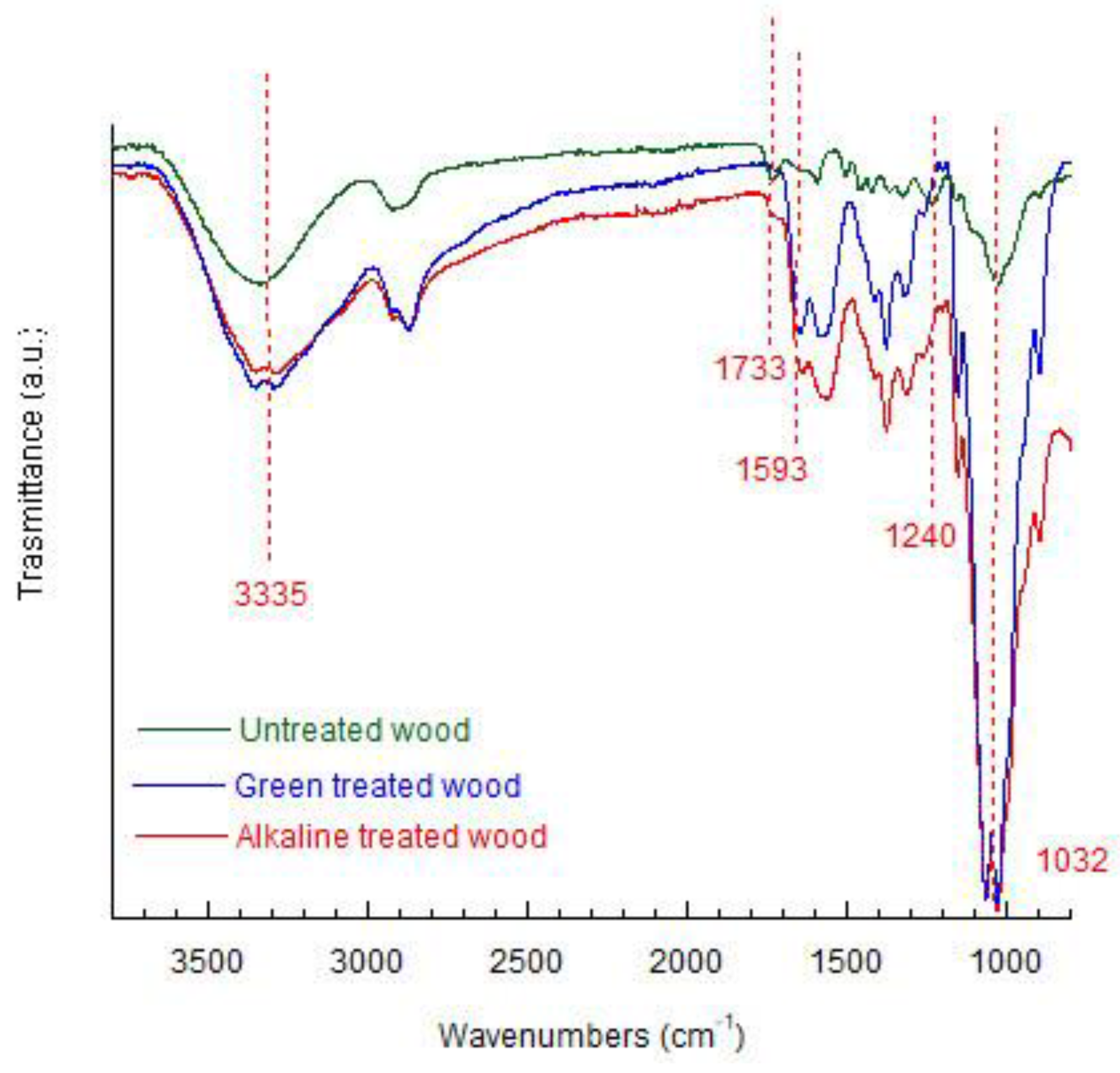

FTIR analyzes were used to investigate the chemical changes undergone by the cell walls of wood during the densification process (see

Figure 3 and

Table 2). The bands at 3378 cm

−1 and 2900 cm

−1 are attributed to O–H and C–H stretching vibration in cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Some characteristic bands were analyzed in untreated wood and densified wood by the two discussed methods. The absorption band at 1733 cm

−1 was attributed to C=O stretching vibration in unconjugated ketones characterizing the hemicellulose. The disappearance of this band in densified wood due to deacetylation indicates the complete dissolution of the hemicellulose following the application of the two methods. Polar functional groups conjugated with the benzene ring showed some changes. The peak at 1593 cm

-1 is attributed to C=C stretching of the aromatic ring in lignin, it is related to unsaturated linkages and aromatic rings present in lignin. With alkali and hydrothermal treatments, it slightly increases. The changes in this area depend on lignin condensation at the expense of conjugated carbonyl groups and to the carboxylation of polysaccharides [

35]. Furthermore, the molecular structure of the lignin changes from glassy to highly elastic and the changes in the band at 1240 cm

-1 (C – H of the guaiacyl ring in the lignin) demonstrate the occurrence of changes in the lignin unit [

39].

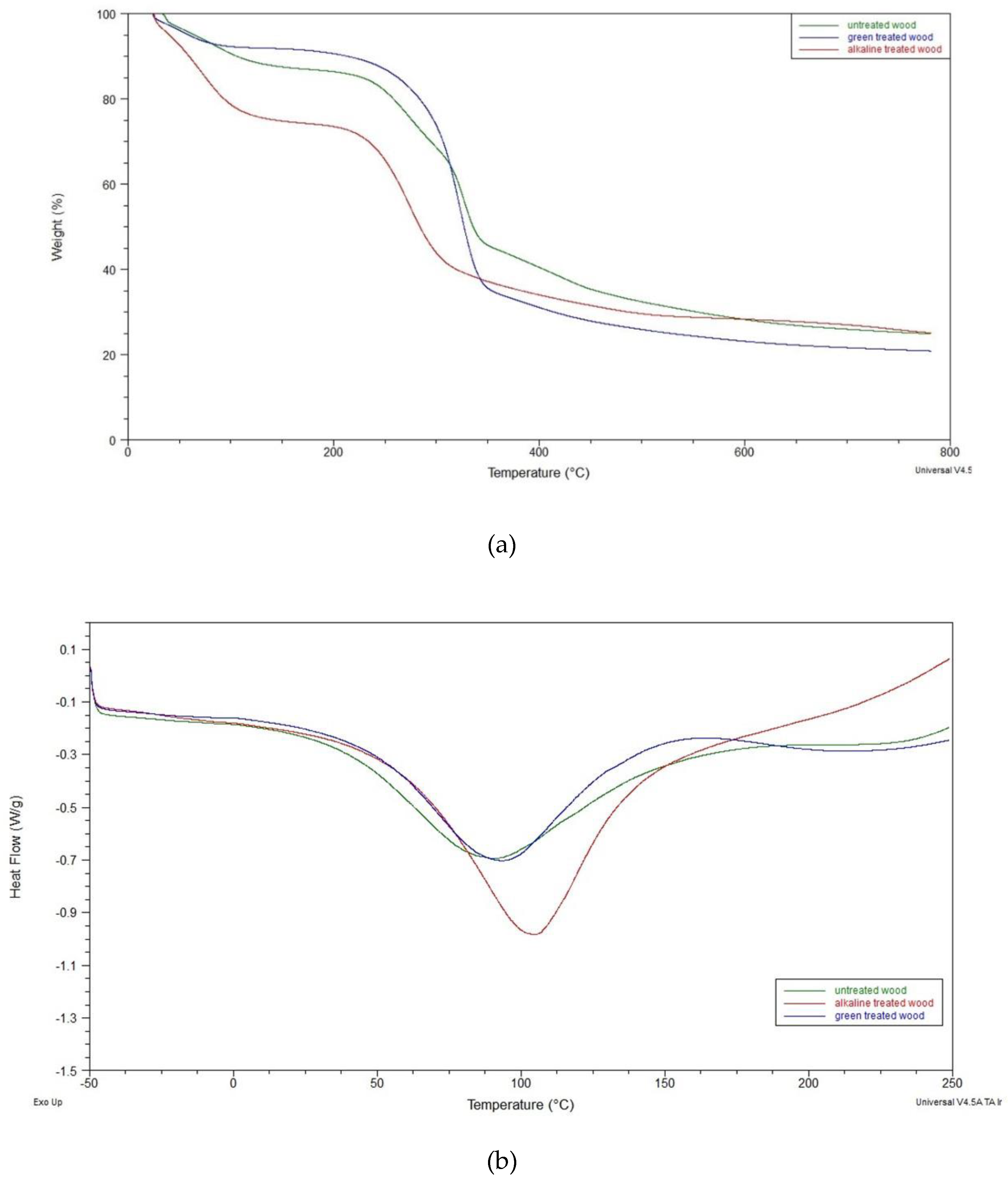

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) is one of the most common techniques used to analyze the thermal stability of materials. The TGA curves of the untreated and densified wood samples are shown in

Figure 4 a).

Figure 4 a) shows that thermal degradation occurs in three stages. The first stage took place in the range from 25 °C to 150 °C with a weight loss of approximately 15% for untreated wood samples, essentially attributable to dehydration and the loss of low molecular weight volatiles. For alkali treated sample the loss weight in the same temperature range is about 20%, while for hydrothermal treated sample is reduced at about 8%.

The second stage of weight loss appears from 150 ◦C to 400 ◦C, due to the thermal degradation of hemicelluloses, cellulose, and lignin. In this stage, the untreated wood samples show a mass loss of about 85% and a temperature corresponding to the maximum degradation rate approximately equal to Tm = 354 ◦C. This thermal parameter seems to increase following the hydrothermal treatment (Tm = 366 ◦C) due to the high lignin content and the dissolution of the hemicelluloses which has a lower degradation temperature than lignin. Conversely, the samples treated with alkali show a lower Tm due to the polymerization of the cellulose in addition to the delignification [

40].

Figure 4 b) shows DSC thermograms of investigated samples. A significant endotherm peak can be observed in the temperature range of approximately 50–180°C for untreated samples, by indicating a high amount of water molecules in the wood fibers. Both treated samples are chracterized by a similar endotherm peak.

3.3. Physical and Mechanical Properties

The oak wood's physical characteristics mainly include density, dry shrinkage coefficient elasticity, and strength. Both alkali and green treatments change the density of oak wood. In fact, cellulose is in a very rigid packing crystalline form, able to form hydrogen bonds responsible for wood strength. Lignin provides a protective cover around the cellulose structure and is strongly interconnected: it binds cellulose fibers and ensures stiffness to the cell walls. Hemicellulose, strongly bound to cellulose fibrils, has an amorphous structure and hydrophilic characteristics. Due to its hydrophilic nature, hemicellulose can absorb the water molecules reducing its dimensional stability.

Alkali treatment is the most known effective surface modification technique for wood. This treatment enables to improve interfacial adhesion by reducing the hemicellulose and lignin covering the wood surface, thereby producing a rough surface of oak wood. The reduction of hemicellulose by alkali treatment is the major cause that induces the decrease of thickness swelling. Reduction of lignin on the wood surface can increase the sites for the cellulose and resin interactions and improve the mechanical properties. Alkali treatment provides an increased accessible surface area of cellulose for contact with the matrix, allowing an efficient stress transfer from matrix to wood and, consequently, improving the bending properties of wood composite [

15].

Similarly, green hydrothermal modification can improve dimensional stability by significantly changing the chemical composition of wood using only water at high temperatures. During hydrothermal modification, mass loss depends on the wood species, heating medium, temperature, and duration of the treatment [

17].

During hydrothermal processes, the released acids reduce pH (from pH 7 to pH measured equal 4.5), the deacetylation of hemicellulose, mass loss, and, hence, the reduction of mechanical strength, that has been visually observed before press densification. The degradation rate of carbohydrates is high in acidic environments and is promoted by the high availability and low crystallinity of hemicelluloses. Further, variations in the acidity of the treatment media increase due to thermal treatment in wet environments and the formation of acetic and formic acids on the basis of the hemicellulose decomposition.

Storage modulus is a critical index to measure the energy storage capability of material after elastic deformation, and is an index of resilience.

Table 3 reports the average values of density and storage modulus for the untreated and treated wood, obtained by considering five tests.

Density and storage modulus of alkali treated and green treated wood sample increased considerably compared to the untreated sample (see

Table 3). This effect demonstrates that the chemical and temperature-pressure treatments increase the elastic properties of the wood samples and decrease their brittleness, probably by high cross-linkage between the celluloses and acidic hydrolysis or degradation of cell walls under high acidity and high temperature.

3.4. Comparison of Hydrothermal Modification and AlkaliTreatment

In light of the above-mentioned results, it is clear that the green method is an effective technique to control and neutralize the destructive effects of acids formed through the demolition of carbohydrates during the alkali treatment. The main advantage is its non-chemical modification that does not cause environmental pollution. The use of water in hydrothermal modification is an eco-sustainable method characterized, by a low-cost removal of sub-waste.

The hydrothermal approach changes the wood properties through the removal of extractives, hemicellulose hydrolysis, and the extraction of lignin and cellulose, but it is certainly less aggressive than the alkali one.

A strong, aggressive and acidic liquid resulting from the condensation of moisture contained in the wood, which turns into vapor during the heating process, is often left after the alkali modification process and must be properly treated.

Therefore, the hydrothermal method is less dangerous for human health, requires less energy and has less environmental impact.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a Teflon-line hydrothermal method based on the use of water at high temperatures is proposed to densify oak wood without threatening the environment. The study was driven by the consideration that wood has been applied in a wide range of forms and in several fields but always limited by its strength and toughness. The cut wood blocks were pressed at 100 °C under a pressure of about 5 MPa for about 1 day to obtain the densified wood. The effects of hydrothermal modification on oak wood’s morphological, physical, mechanical, and chemical properties have been examined. These properties have been compared to the oak wood modification by a traditional alkali method finding promising results.

Overall, hydrothermally treated wood offers several advantages in terms of technological performance and properties improvement of end products compared to ones obtained through the traditional alkali method. In particular, the density and the storage modulus of treated sample increased considerably compared to the untreated sample, finding a modulus improvement of 88% and 125% for alkali treated and green treated wood respectively and, hence, of 19.6% for green wood respect to the alkali treated material.

The results highlighted potentials of a hydrothermal densification method for the development of new functional wood materials for future applications in the direction of the environmental sustainability.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank F. Docimo and M. R.Marcedula for their support of the experiments, Valerio Di Giulio the wood craftsman, Ph.D. Leandro Maio, and Vittorio Memmolo of the Industrial Engineering Department of the University of Study Federico II for their support of getting oak wood.

References

- Navi, P.; Heger, F. Combined Densification and Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical Processing of Wood. MRS Bull. 2004, 29, 332–336. [CrossRef]

- Kamke, F.A.; Sizemore, H. Viscoelastic thermal compression of wood., 2008, US Patent No. US7404422B2.

- Bekhta, P.; Proszyk, S.; Krystofiak, T. Colour in short-term thermo-mechanically densified veneer of various wood species. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2014, 72, 785–797. [CrossRef]

- Kutnar, A.; Kamke, F.A.; Sernek, M. The mechanical properties of densified VTC wood relevant for structural composites. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2008, 66, 439–446. [CrossRef]

- Laine, K.; Belt, T.; Rautkari, L.; Ramsay, J.; Hill, C.A.S.; Hughes, M. Measuring the thickness swelling and set-recovery of densified and thermally modified Scots pine solid wood. J. Mater. Sci. 2013, 48, 8530–8538. [CrossRef]

- Blomberg, J.; Persson, B.; Blomberg, A. Effects of semi-isostatic densification of wood on the variation in strength properties with density. Wood Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 339–350. [CrossRef]

- Kutnar, A.; Kamke, F.A.; Sernek, M. Density profile and morphology of viscoelastic thermal compressed wood. Wood Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 57–68. [CrossRef]

- Rautkari, L.; Properzi, M.;.Pichelin, F.; Hughes, M. Properties and set-recovery of surface densified Norway spruce and European beech, Wood Sci Technol 2010, 44(4), 679–691.

- Laskowska, A. The Influence of Process Parameters on the Density Profile and Hardness of Surface-densified Birch Wood (Betula pendula Roth). BioResources 2017, 12, 6011-6023. [CrossRef]

- Pelit. H.; Budakçı, M.; Sönmez, A. Density and some mechanical properties of densified and heat post-treated Uludağ fr, linden and black poplar woods, Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2018, 76(1), 79–87.

- Sandberg, D.; Haller, P.; Navi, P. Thermo-hydro and thermo-hydro-mechanical wood processing: An opportunity for future environmentally friendly wood products. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2013, 8, 64–88. [CrossRef]

- Pelit, H.; Sönmez, A.; Budakçı, M. Effects of ThermoWood® Process Combined with Thermo-Mechanical Densification on some Physical Properties of Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris L.). BioResources 2014, 9, 4552-4567. [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.-H.; Mariotti, N.; Cloutier, A.; Koubaa, A.; Blanchet, P. Densification of wood veneers by compression combined with heat and steam. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2011, 70, 155–163. [CrossRef]

- Ugovšek, A.; Kamke, F.A.; Sernek, M.; Kutnar, A. Bending performance of 3-layer beech (Fagus sylvativa L.) and Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) VTC composites bonded with phenol-formaldehyde adhesive and liquefied wood, Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2013, 71(4), 507–514.

- Song, J.; Chen, C.; Zhu, S.; Zhu, M.; Dai, J.; Ray, U.; Li, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Li, Y.; Quispe, N.; et al. Processing bulk natural wood into a high-performance structural material. Nature 2018, 554, 224–228. [CrossRef]

- Navi, P.; Girardet, F. Effects of Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical Treatment on the Structure and Properties of Wood. Holzforschung 2000, 54, 287–293. [CrossRef]

- Blomberg, J.; Persson, B. Plastic deformation in small clear pieces of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) during densification with the CaLignum process. J. Wood Sci. 2004, 50, 307–314. [CrossRef]

- Kamke, F.A.; Sizemore, H. Viscoelastic thermal compression of wood, 2008, US Patent No. US7404422B2.

- Kutnar, A.; Kamke, F.A. Compression of wood under saturated steam, superheated steam, and transient conditions at 150°C, 160°C, and 170°C. Wood Sci. Technol. 2010, 46, 73–88. [CrossRef]

- Kamke, F.A.; Kutnar, A. Influence of stress level on compression deformation of wood in 170°C transient steam conditions. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2011, 6, 105–111. [CrossRef]

- Kutnar, A.; Kamke, F.A.; Sernek, M. Density profile and morphology of viscoelastic thermal compressed wood. Wood Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 57–68. [CrossRef]

- Rautkari, L.; Kamke, F.A.; Hughes, M. Density profile relation to hardness of viscoelastic thermal compressed (VTC) wood composite. Wood Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 693–705. [CrossRef]

- Kutnar, A.; Kamke, F.A.; Sernek, M. The mechanical properties of densified VTC wood relevant for structural composites. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2008, 66, 439–446. [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.-H.; Mariotti, N.; Cloutier, A.; Koubaa, A.; Blanchet, P. Densification of wood veneers by compression combined with heat and steam. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2011, 70, 155–163. [CrossRef]

- Welzbacher, C.R.; Wehsener, J.; Rapp, A.O.; Haller, P. Thermo-mechanical densification combined with thermal modification of Norway spruce (Picea abies Karst) in industrial scale – Dimensional stability and durability aspects. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2007, 66, 39–49. [CrossRef]

- Tabarsa, T.; Chui, Y.H. Effects of hot-pressing on properties of white spruce, For. Prod. J. 1997, 47, 71-76.

- Rautkari, L.; Laine, K.; Laflin, N.; Hughes, M. Surface modification of Scots pine: the effect of process parameters on the through thickness density profile. J. Mater. Sci. 2011, 46, 4780–4786. [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, A.; Leban, J.-.-M.; Zanetti, M.; Pichelin, F.; Wieland, S.; Properzi, M. Surface finishes by mechanically induced wood surface fusion. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2005, 63, 251–255. [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Lamason, C.; Li, L. Interactive effect of surface densification and post-heat-treatment on aspen wood. J. Mech. Work. Technol. 2010, 210, 293–296. [CrossRef]

- Ilanidis, D.; Stagge, S.; Jönsson, L.J.; Martín, C. Hydrothermal Pretreatment of Wheat Straw: Effects of Temperature and Acidity on Byproduct Formation and Inhibition of Enzymatic Hydrolysis and Ethanolic Fermentation. Agronomy 2021, 11, 487. [CrossRef]

- Endo, K.; Obataya, E.; Zeniya, N.; Matsuo, M. Effects of heating humidity on the physical properties of hydrothermally treated spruce wood. Wood Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 1161–1179. [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Lin, R.; Lam, C.H.; Wu, H.; Tsui, T.-H.; Yu, Y. Recent advances and challenges of inter-disciplinary biomass valorization by integrating hydrothermal and biological techniques. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135. [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.; Abdullah, U.H.; Ashaari, Z.; Hamid, N.H.; Hua, L.S. Hydrothermal Modification of Wood: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 2612. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, L.; Shi, S.Q. Effect of thermal treatment with water, H2SO4 and NaOH aqueous solution on color, cell wall and chemical structure of poplar wood. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17735. [CrossRef]

- Kačík, F.; Solár, R. Analytical Chemistry of Wood, 1st ed.; Technical University in Zvolen: Zvolen, Slovakia, 2000, 369.

- Assor, C.; Placet, V.; Chabbert, B.; Habrant, A.; Lapierre, C.; Pollet, B.; Perré, P. Concomitant Changes in Viscoelastic Properties and Amorphous Polymers during the Hydrothermal Treatment of Hardwood and Softwood. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 6830–6837. [CrossRef]

- Seifert, V.K. Űber ein neues Verfahren zur Schnellbestimmung der Rein-Cellulose. Das Pap. 1956, 10, 301–306.

- González-Peña, M.M.; Curling, S.F.; Hale, M.D. On the effect of heat on the chemical composition and dimensions of thermally-modified wood. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2009, 94, 2184–2193. [CrossRef]

- Lehto, J.; Louhelainen, J.; Kłosińska, T.; Drożdżek, M.; Alén, R. Characterization of alkali-extracted wood by FTIR-ATR spectroscopy. Biomass- Convers. Biorefinery 2018, 8, 847–855. [CrossRef]

- Shapchenkova, O.; Loskutov, S.; Aniskina, A.; Börcsök, Z.; Pásztory, Z. Thermal characterization of wood of nine European tree species: thermogravimetry and differential scanning calorimetry in an air atmosphere. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2021, 80, 409–417. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).