Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Soran, A.; Ozmen, V.; Ozbas, S.; et al. Primary Surgery with Systemic Therapy in Patients with de Novo Stage IV Breast Cancer: 10-year Follow-up; Protocol MF07-01 Randomized Clinical Trial. J Am Coll Surg 2021, 233, 742–751.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwase, T.; Shrimanker, T.V.; Rodriguez-Bautista, R.; et al. Changes in Overall Survival over Time for Patients with de novo Metastatic Breast Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiser, M.R. AJCC 8th Edition: Colorectal Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2018, 25, 1454–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lababede, O.; Meziane, M.A. The Eighth Edition of TNM Staging of Lung Cancer: Reference Chart and Diagrams. Oncologis 2018, 23, 844–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berek, J.S.; Renz, M.; Kehoe, S.; Kumar, L.; Friedlander, M. Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum: 2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2021, 155 (Suppl. 1), 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamartina, L.; Grani, G.; Arvat, E.; et al. 8th edition of the AJCC/TNM staging system of thyroid cancer: what to expect (ITCO#2). Endocr Relat Cancer 2018, 25, L7–L11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamirisa, N.P.; Ren, Y.; Campbell, B.M.; et al. Treatment Patterns and Outcomes of Women with Breast Cancer and Supraclavicular Nodal Metastases. Ann Surg Oncol 2021, 28, 2146–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plichta, J.K.; Ren, Y.; Thomas, S.M.; et al. Implications for Breast Cancer Restaging Based on the 8th Edition AJCC Staging Manual. Ann Surg 2020, 271, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, B.; Chen, J.; et al. A Novel Nomogram Model to Identify Candidates and Predict the Possibility of Benefit From Primary Tumor Resection Among Female Patients With Metastatic Infiltrating Duct Carcinoma of the Breast: A Large Cohort Study. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 798016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommalapati, A.; Tella, S.H.; Goyal, G.; Ganti, A.K.; Krishnamurthy, J.; Tandra, P.K. A prognostic scoring model for survival after locoregional therapy in de novo stage IV breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018, 170, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plichta, J.K.; Thomas, S.M.; Sergesketter, A.R.; et al. A Novel Staging System for De Novo Metastatic Breast Cancer Refines Prognostic Estimates. Ann Surg 2022, 275, 784–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soran, A.; Dogan, L.; Isik, A.; et al. The Effect of Primary Surgery in Patients with De Novo Stage IV Breast Cancer with Bone Metastasis Only (Protocol BOMET MF 14-01): A Multi-Center, Prospective Registry Study. Ann Surg Oncol 2021, 28, 5048–5057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, K.; Douglas, E.; Romitti, P.A.; Thomas, A. Epidemiology of De Novo Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin Breast Cancer 2021, 21, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weichselbaum, R.R.; Hellman, S. Oligometastases revisited. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2011, 8, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, F.; Paluch-Shimon, S.; Senkus, E.; et al. 5th ESO-ESMO international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 5). Ann Oncol 2020, 31, 1623–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lievens, Y.; Guckenberger, M.; Gomez, D.; et al. Defining oligometastatic disease from a radiation oncology perspective: An ESTRO-ASTRO consensus document. Radiother Oncol 2020, 148, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, A.T.; Thukral, A.D.; Hwang, W.T.; Solin, L.J.; Vapiwala, N. Incidence and patterns of distant metastases for patients with early-stage breast cancer after breast conservation treatment. Clin Breast Cancer 2013, 13, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Khan, S.A.; Chrischilles, E.A.; Schroeder, M.C. Initial Surgery and Survival in Stage IV Breast Cancer in the United States, 1988-2011. JAMA Surg 2016, 151, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, W.O.; Thomas, S.M.; Blitzblau, R.C.; et al. Surgical Resection of the Primary Tumor in Women With De Novo Stage IV Breast Cancer: Contemporary Practice Patterns and Survival Analysis. Ann Surg 2019, 269, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons-Tostivint, E.; Kirova, Y.; Lusque, A.; et al. Survival Impact of Locoregional Treatment of the Primary Tumor in De Novo Metastatic Breast Cancers in a Large Multicentric Cohort Study: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2019, 26, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Tarruella, S.; Escudero, M.J.; Pollan, M.; et al. Survival impact of primary tumor resection in de novo metastatic breast cancer patients (GEICAM/El Alamo Registry). Sci Rep 2019, 9, 20081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cady, B.; Nathan, N.R.; Michaelson, J.S.; Golshan, M.; Smith, B.L. Matched pair analyses of stage IV breast cancer with or without resection of primary breast site. Ann Surg Oncol 2008, 15, 3384–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shien, T.; Kinoshita, T.; Shimizu, C.; et al. Primary tumor resection improves the survival of younger patients with metastatic breast cancer. Oncol Rep 2009, 21, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Deng, G.; Wang, J.; et al. Could local surgery improve survival in de novo stage IV breast cancer? BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Co, T.H.M.; Ng, J.; Kwong, A. Long term survival study of de-novo metastatic breast cancers with or without primary tumour resection. Cancer Treat Res Commun 2019, 20, 100148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Touk, N.A.; Fikry, A.; Fouda, E.Y. The benefit of locoregional surgical intervention in metastatic breast cancer at initial presentation. Cancer Research Journal 2016, 4, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badwe, R.; Hawaldar, R.; Nair, N.; et al. Locoregional treatment versus no treatment of the primary tumour in metastatic breast cancer: an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2015, 16, 1380–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Zhao, F.; Goldstein, L.J.; et al. Early Local Therapy for the Primary Site in De Novo Stage IV Breast Cancer: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial (EA2108). J Clin Onco 2022, 40, 978–987, [published correction appears in J Clin Oncol 2022, 40, 1392. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.22.00666]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shien, T.; Nakamura, K.; Shibata, T.; et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing primary tumour resection plus systemic therapy with systemic therapy alone in metastatic breast cancer (PRIM-BC): Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG1017. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2012, 42, 970–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Sun, J.; Kong, L.; Wang, H. Breast surgery for patients with de novo metastatic breast cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Surg Oncol 2024, 50, 107308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Hong, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. Clinical Evidence for Locoregional Surgery of the Primary Tumor in Patients with De Novo Stage IV Breast Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2021, 28, 5059–5070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Zou, Y.; Zheng, S.; et al. Primary tumor resection in stage IV breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol 2018, 44, 1504–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.M.; Miles, D.; Kim, S.B.; et al. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (CLEOPATRA): end-of-study results from a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2020, 21, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slamon, D.J.; Diéras, V.; Rugo, H.S.; et al. Overall Survival With Palbociclib Plus Letrozole in Advanced Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2024, 42, 994–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slamon, D.J.; Neven, P.; Chia, S.; et al. Ribociclib plus fulvestrant for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative advanced breast cancer in the phase III randomized MONALEESA-3 trial: updated overall survival. Ann Oncol 2021, 32, 1015–1024, [published correction appears in Ann Oncol 2021, 32, 1307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2021.07.011]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes, J.; Cescon, D.W.; Rugo, H.S.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-355): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 1817–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, B.A.; Vallejo, C.T.; Romero, A.O.; et al. Prognostic impact of metastatic pattern in stage IV breast cancer at initial diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017, 161, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press, D.J.; Miller, M.E.; Liederbach, E.; Yao, K.; Huo, D. De novo metastasis in breast cancer: occurrence and overall survival stratified by molecular subtype. Clin Exp Metastasis 2017, 34, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobbezoo, D.J.; van Kampen, R.J.; Voogd, A.C.; et al. Prognosis of metastatic breast cancer subtypes: the hormone receptor/HER2-positive subtype is associated with the most favorable outcome. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013, 141, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Wu, J.; Ding, S.; et al. Subdivision of M1 Stage for De Novo Metastatic Breast Cancer to Better Predict Prognosis and Response to Primary Tumor Surgery. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2019, 17, 1521–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, T.K.; Chae, B.J.; Kim, S.J.; et al. Identifying long-term survivors among metastatic breast cancer patients undergoing primary tumor surgery. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017, 165, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kommalapati, A.; Tella, S.H.; Goyal, G.; Ganti, A.K.; Krishnamurthy, J.; Tandra, P.K. A prognostic scoring model for survival after locoregional therapy in de novo stage IV breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018, 170, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plichta, J.K.; Thomas, S.M.; Hayes, D.F.; et al. Novel Prognostic Staging System for Patients With De Novo Metastatic Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2023, 41, 2546–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Holland-Letz, T.; Wallwiener, M.; et al. Circulating free DNA integrity and concentration as independent prognostic markers in metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018, 169, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pairawan, S.; Hess, K.R.; Janku, F.; et al. Cell-free Circulating Tumor DNA Variant Allele Frequency Associates with Survival in Metastatic Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2020, 26, 1924–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Shen, Y. Prognostic factors and survival according to tumour subtype in women presenting with breast cancer bone metastases at initial diagnosis: a SEER-based study. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, X.; Liao, X.; Li, J.; Tang, P.; Jiang, J. Clinical Outcomes of N3 Breast Cancer: A Real-World Study of a Single Institution and the US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Database. Cancer Manag Res 2020, 12, 5331–5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Chen, H.; Dai, Y.; Bao, B.; Tian, L.; Chen, Y. Nontherapeutic Risk Factors of Different Grouped Stage IIIC Breast Cancer Patients’ Mortality: A Study of the US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database. Breast J 2022, 2022, 6705052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

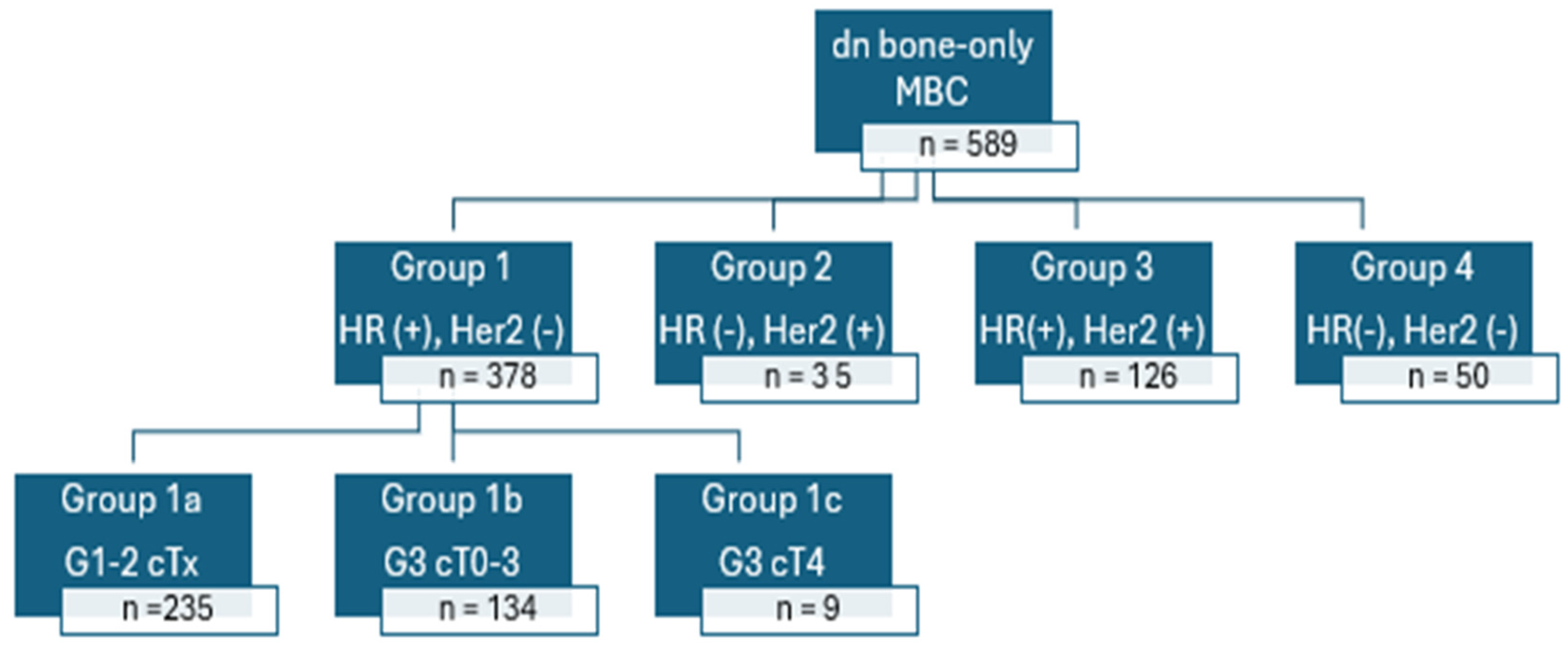

| Group 1: HR(+); HER2(-) |

| Group 1a: HR(+); HER2(-); Grade 1-2; cTany |

| Group 1b: HR(+); HER2(-); Grade 3; cT0-3 |

| Group 1c: HR(+); HER2(-); Grade 3; cT4 |

| Group 2: HR(-); HER2(+) |

| Group 3: HR(+); HER2(+) |

| Group 4: HR(-); HER2(-) |

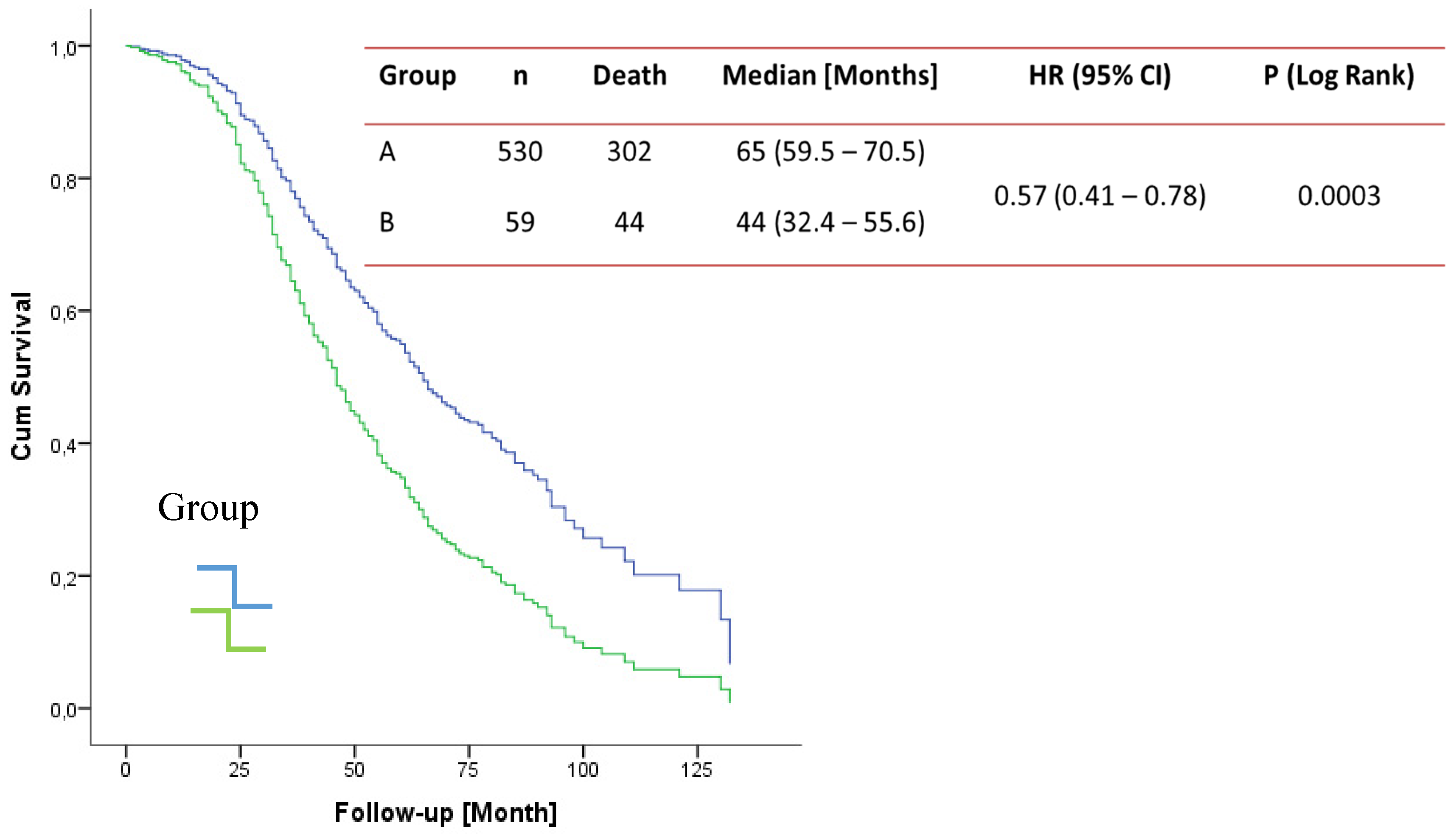

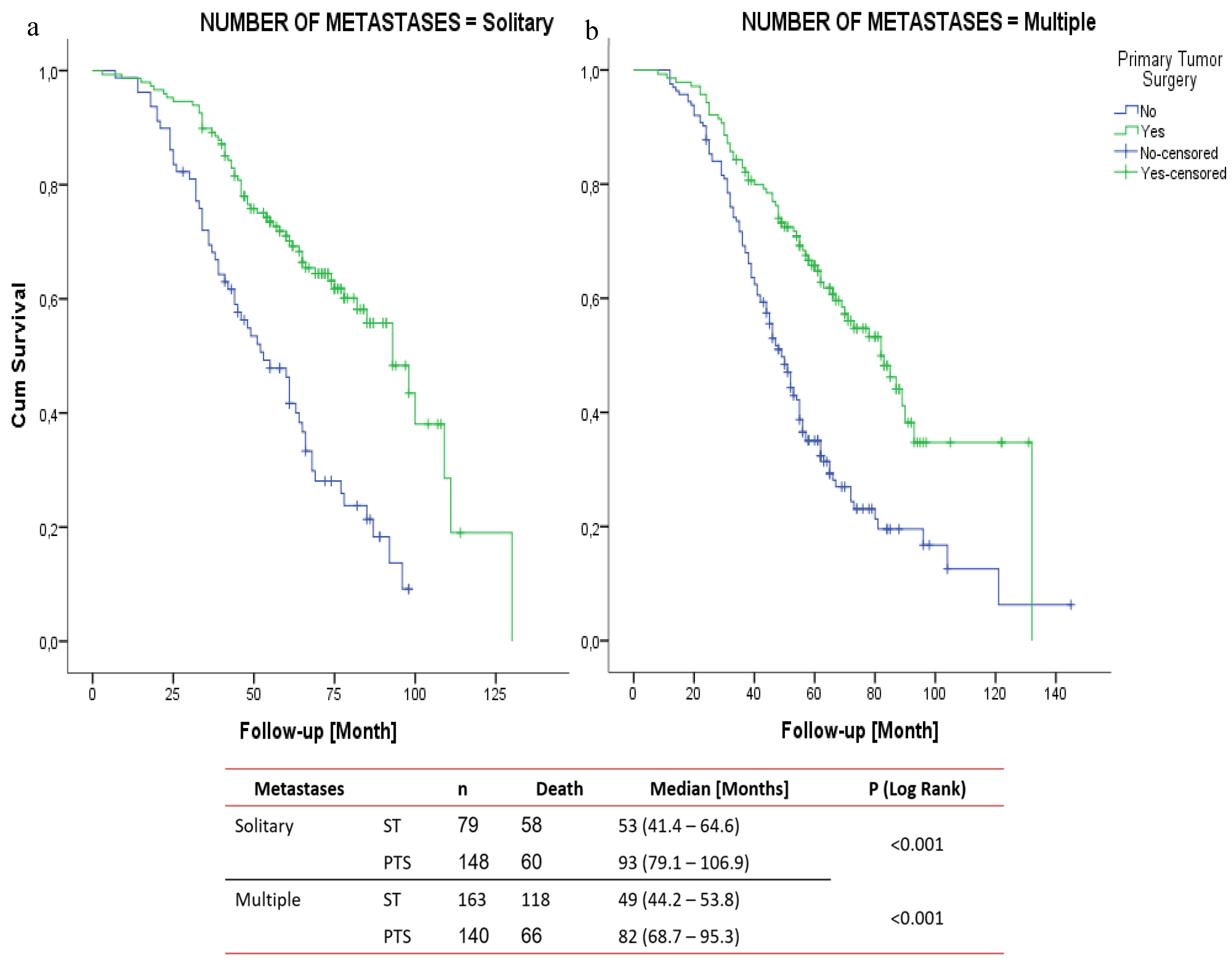

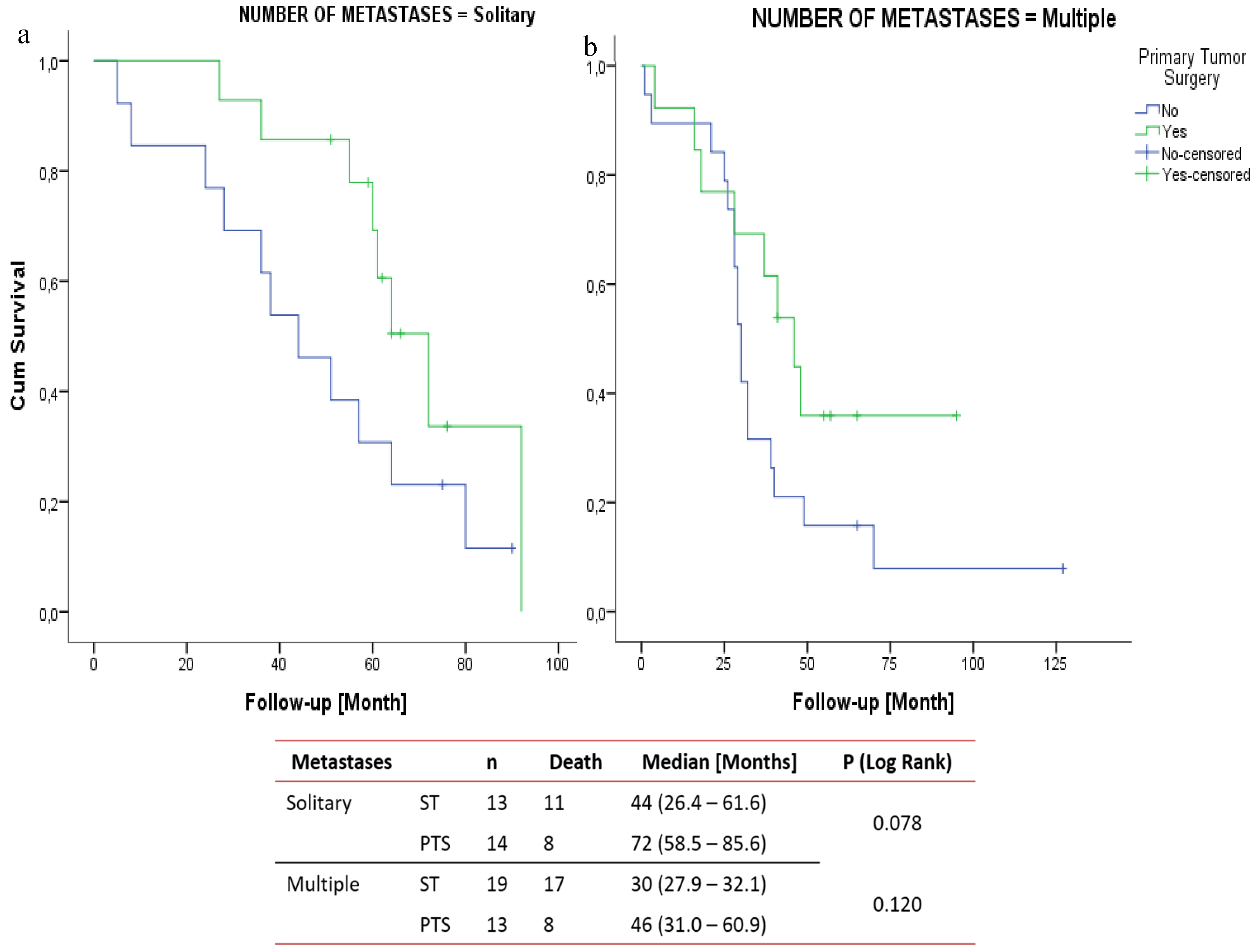

| Group 1a, b and Group 2 and 3 were classified as Group A and group 1c and group 4 classified as Group B. HR: Hormone receptor, Her 2: Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, T: tumor size |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).