Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

28 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

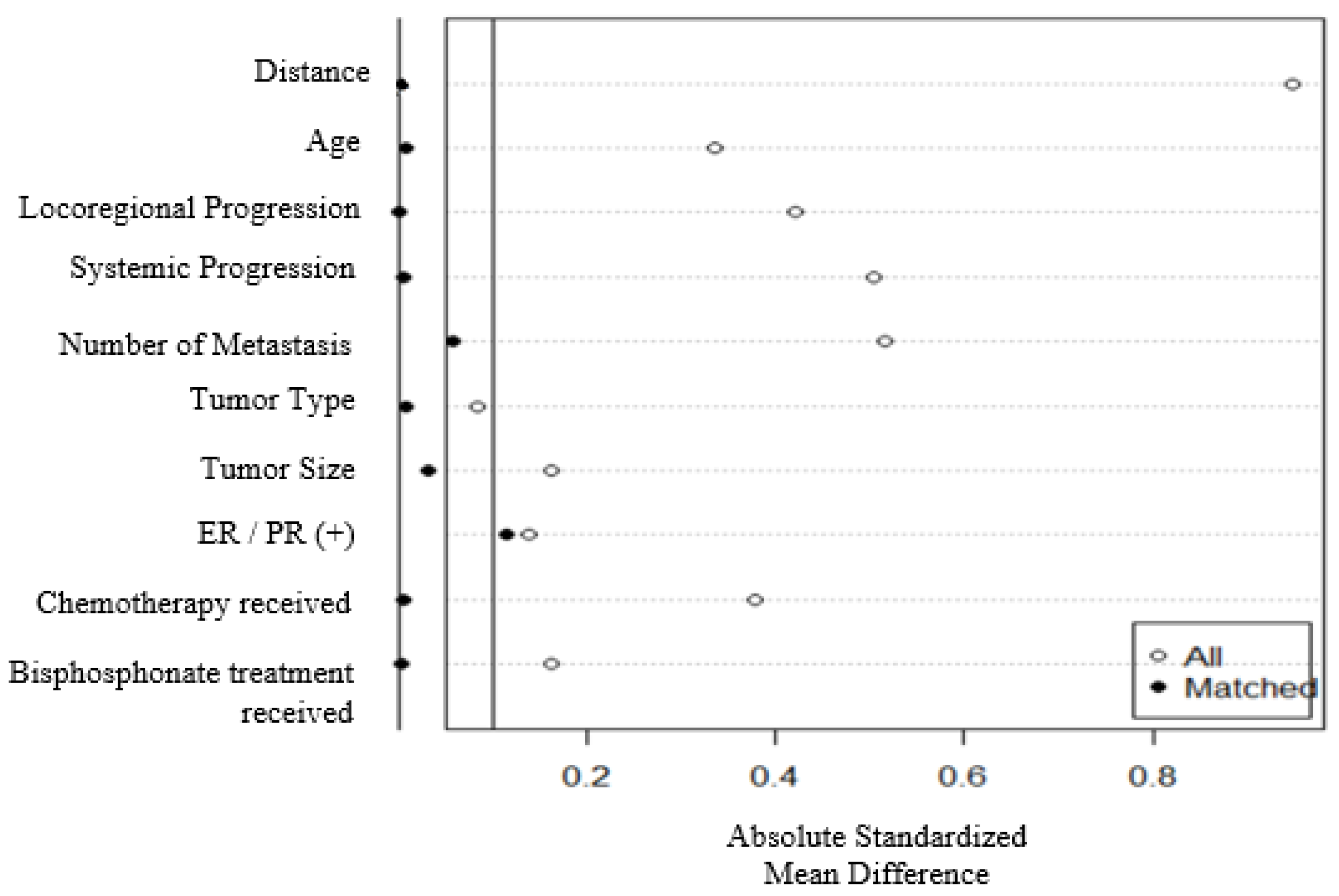

Statistical Analysis

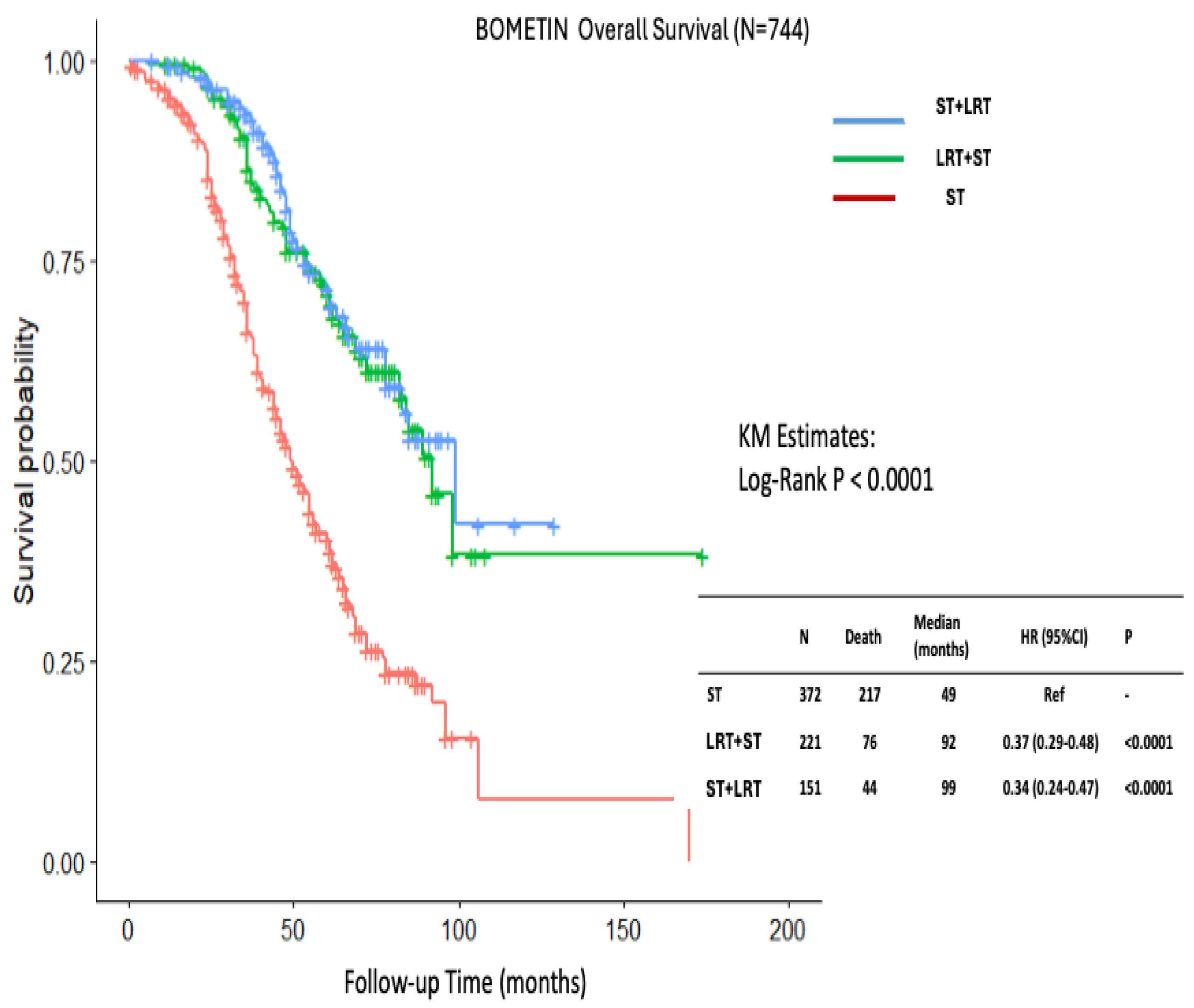

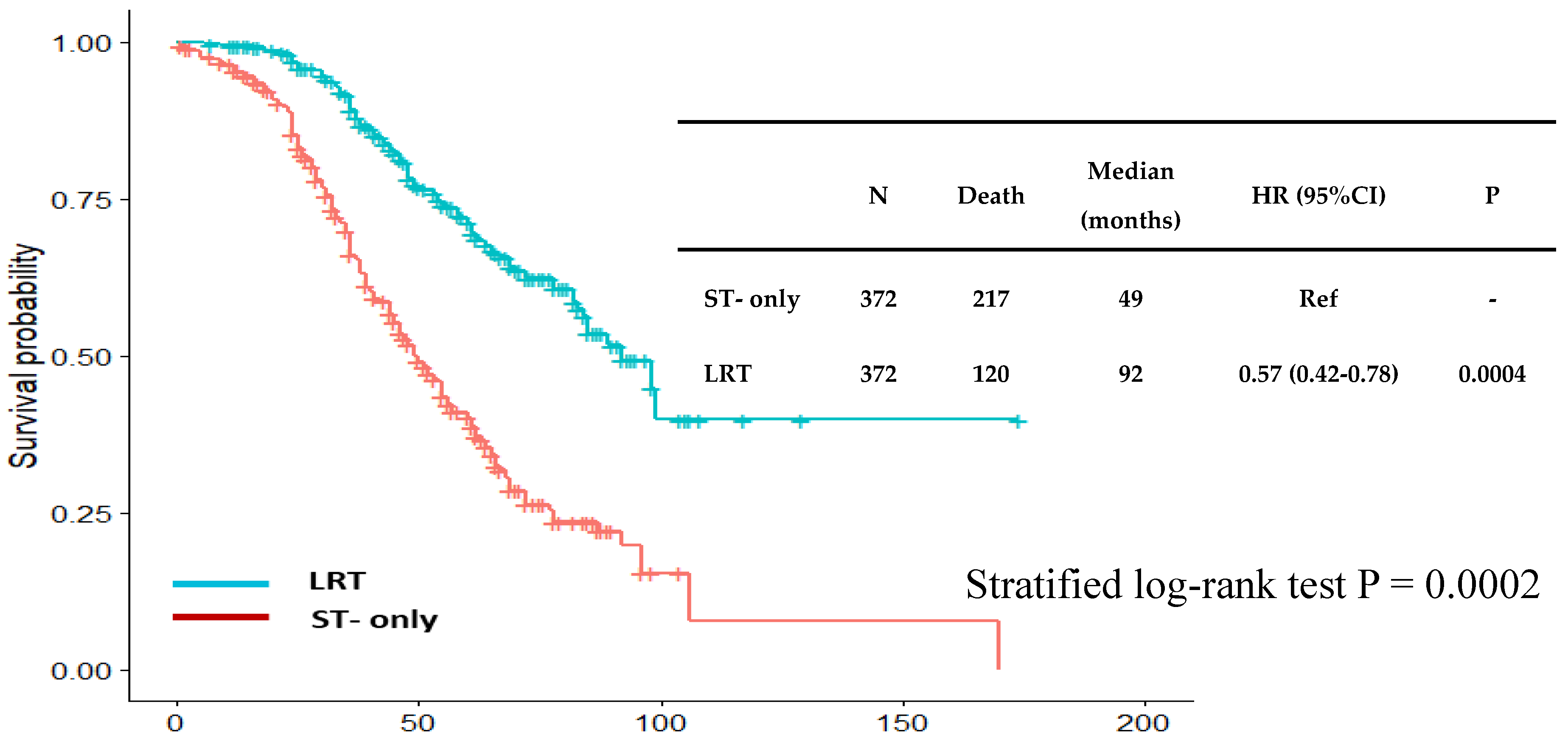

Results

Discussion

- Atilla Soran: study design, data collection, statistical analysis, data interpretation and editing of the manuscript.

- Berk Goktepe: study design, statistical analysis, writing of the manuscript.

- Berkay Demirors: study design, statistical analysis, writing of the manuscript.

- Ozgur Aytac: study design, statistical analysis, writing of the manuscript.

- Serdar Ozbas: study design, statistical analysis, writing of the manuscript.

- Lutfi Dogan: study design, statistical analysis, writing of the manuscript.

- Didem Can Trablus: study design, statistical analysis, writing of the manuscript.

- Jamila Al-Azhri: study design, statistical analysis, writing of the manuscript.

- Kazım Senol: study design, data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Shruti Zaveri: study design, data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Salyna Meas: study design, data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Umut Demirci: study design, data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Hasan Karanlik: study design, data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Aykut Soyder: data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Ahmet Dag: data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Ahmet Bilici: data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Mutlu Dogan: data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Mehmet Ali Nahit Sendur: data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Hande Koksal: data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Mehmet Ali Gulcelik: data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Neslihan Cabioglu: data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Levent Yeniay: data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Zafer Utkan: data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Nuri Karadurmus: data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Gul Daglar: data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Turgay Simsek: data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Birol Yildiz: data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Cihan Uras: data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Mustafa Tukenmez: data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Cihangir Ozaslan: data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Niyazi Karaman: data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Arda Isik: data interpretation, editing of the manuscript

- Efe Sezgin: study design, statistical analysis, writing of the manuscript

- Vahit Ozmen: study design, statistical analysis, writing of the manuscript

- Anthony Lucci: study design, statistical analysis, writing of the manuscript

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LRT | Loco-regional treatment |

| ST | Systemic therapy |

| OS | Overall survival |

| dnBOMBC | De novo bone-only metastatic breast cancer |

| dnMBC | De novo metastatic breast cancer |

| HR | Hormone receptor |

| HER2 | Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| ER | Estrogen receptor |

| PR | Progesterone receptor |

| LP | locoregional progression |

| LRT | locoregional treatment |

| SP | Systemic progression |

| CDK | cyclin-dependent kinase |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| OS | Overall survival |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

References

- Wagle NS, Nogueira L, Devasia TP, Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Islami F, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2025. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Soran A, Dogan L, Isik A, Ozbas S, Trabulus DC, Demirci U, et al. The Effect of Primary Surgery in Patients with De Novo Stage IV Breast Cancer with Bone Metastasis Only (Protocol BOMET MF 14-01): A Multi-Center, Prospective Registry Study: A. Soran et al. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2021;28(9):5048-57. [CrossRef]

- Iwase T, Shrimanker TV, Rodriguez-Bautista R, Sahin O, James A, Wu J, et al. Changes in overall survival over time for patients with de novo metastatic breast cancer. Cancers. 2021;13(11):2650. [CrossRef]

- Eng LG, Dawood S, Sopik V, Haaland B, Tan PS, Bhoo-Pathy N, et al. Ten-year survival in women with primary stage IV breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2016;160(1):145-52. [CrossRef]

- Gupta RK, Roy AM, Gupta A, Takabe K, Dhakal A, Opyrchal M, et al. Systemic therapy de-escalation in early-stage triple-negative breast cancer: dawn of a new era? Cancers. 2022;14(8):1856. [CrossRef]

- Liu B, Liu H, Liu M. Aggressive local therapy for de novo metastatic breast cancer: Challenges and updates. Oncology Reports. 2023;50(3):163.

- Gradishar WJ, Moran MS, Abraham J, Abramson V, Aft R, Agnese D, et al. Breast cancer, version 3.2024, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2024;22(5):331-57. [CrossRef]

- Gennari A, André F, Barrios C, Cortes J, de Azambuja E, DeMichele A, et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer☆. Annals of oncology. 2021;32(12):1475-95. [CrossRef]

- Gera R, Chehade HEH, Wazir U, Tayeh S, Kasem A, Mokbel K. Locoregional therapy of the primary tumour in de novo stage IV breast cancer in 216 066 patients: A meta-analysis. Scientific reports. 2020;10(1):2952. [CrossRef]

- Vohra NA, Brinkley J, Kachare S, Muzaffar M. Primary tumor resection in metastatic breast cancer: A propensity-matched analysis, 1988-2011 SEER data base. The breast journal. 2018;24(4):549-54.

- Xiao W, Zou Y, Zheng S, Hu X, Liu P, Xie X, et al. Primary tumor resection in stage IV breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2018;44(10):1504-12. [CrossRef]

- Badwe R, Hawaldar R, Nair N, Kaushik R, Parmar V, Siddique S, et al. Locoregional treatment versus no treatment of the primary tumour in metastatic breast cancer: an open-label randomised controlled trial. The lancet oncology. 2015;16(13):1380-8. [CrossRef]

- Abo-Touk N, Fikry A, Fouda E. The benefit of locoregional surgical intervention in metastatic breast cancer at initial presentation. Cancer Research Journal. 2016;4(2):32-6. [CrossRef]

- Soran A, Ozmen V, Ozbas S, Karanlik H, Muslumanoglu M, Igci A, et al. Randomized trial comparing resection of primary tumor with no surgery in stage IV breast cancer at presentation: protocol MF07-01. Annals of surgical oncology. 2018;25(11):3141-9. [CrossRef]

- Pulido C, Vendrell I, Ferreira AR, Casimiro S, Mansinho A, Alho I, et al. Bone metastasis risk factors in breast cancer. Ecancermedicalscience. 2017;11:715. [CrossRef]

- Austin, PC. The use of propensity score methods with survival or time-to-event outcomes: reporting measures of effect similar to those used in randomized experiments. Statistics in medicine. 2014;33(7):1242-58. [CrossRef]

- Austin PC, Stuart EA. Optimal full matching for survival outcomes: a method that merits more widespread use. Statistics in medicine. 2015;34(30):3949-67. [CrossRef]

- Hansen BB. Full matching in an observational study of coaching for the SAT. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2004;99(467):609-18. [CrossRef]

- Stuart EA, Green KM. Using full matching to estimate causal effects in nonexperimental studies: examining the relationship between adolescent marijuana use and adult outcomes. Developmental psychology. 2008;44(2):395. [CrossRef]

- Burstein H, Curigliano G, Thürlimann B, Weber W, Poortmans P, Regan M, et al. Customizing local and systemic therapies for women with early breast cancer: the St. Gallen International Consensus Guidelines for treatment of early breast cancer 2021. Annals of oncology. 2021;32(10):1216-35. [CrossRef]

- Curigliano G, Burstein H, Gnant M, Loibl S, Cameron D, Regan M, et al. Corrigendum to “Understanding breast cancer complexity to improve patient outcomes: The St Gallen International Consensus Conference for the Primary Therapy of Individuals with Early Breast Cancer 2023”:[Annals of Oncology 34 (2023) 970-986]. Annals of Oncology. 2025;36(3):351.

- Loibl S, André F, Bachelot T, Barrios C, Bergh J, Burstein H, et al. Early breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up☆. Annals of Oncology. 2024;35(2):159-82. [CrossRef]

- Im S-A, Gennari A, Park Y, Kim J, Jiang Z-F, Gupta S, et al. Pan-Asian adapted ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. ESMO open. 2023;8(3):101541. [CrossRef]

- Yao Y-B, Zheng X-E, Luo X-B, Wu A-M. Incidence, prognosis and nomograms of breast cancer with bone metastases at initial diagnosis: a large population-based study. American journal of translational research. 2021;13(9):10248.

- Marie L, Braik D, Abdel-Razeq N, Abu-Fares H, Al-Thunaibat A, Abdel-Razeq H. Clinical characteristics, prognostic factors and treatment outcomes of patients with bone-only metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Management and Research. 2022:2519-31. [CrossRef]

- Soran A, Ozmen V, Ozbas S, Karanlik H, Muslumanoglu M, Igci A, et al. Primary surgery with systemic therapy in patients with de novo stage IV breast cancer: 10-year follow-up; protocol MF07-01 randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2021;233(6):742-51. e5. [CrossRef]

- Lane WO, Thomas SM, Blitzblau RC, Plichta JK, Rosenberger LH, Fayanju OM, et al. Surgical resection of the primary tumor in women with de novo stage IV breast cancer: contemporary practice patterns and survival analysis. Annals of surgery. 2019;269(3):537-44.

- Lopez-Tarruella S, Escudero M, Pollan M, Martín M, Jara C, Bermejo B, et al. Survival impact of primary tumor resection in de novo metastatic breast cancer patients (GEICAM/El Alamo Registry). Scientific reports. 2019;9(1):20081. [CrossRef]

- Wang K, Shi Y, Li Z-Y, Xiao Y-L, Li J, Zhang X, et al. Metastatic pattern discriminates survival benefit of primary surgery for de novo stage IV breast cancer: A real-world observational study. European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2019;45(8):1364-72. [CrossRef]

- Khan SA, Zhao F, Goldstein LJ, Cella D, Basik M, Golshan M, et al. Early local therapy for the primary site in de novo stage IV breast cancer: results of a randomized clinical trial (E2108). Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2022;40(9):978-87. [CrossRef]

- Shien T, Nakamura K, Shibata T, Kinoshita T, Aogi K, Fujisawa T, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing primary tumour resection plus systemic therapy with systemic therapy alone in metastatic breast cancer (PRIM-BC): Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG1017. Japanese journal of clinical oncology. 2012;42(10):970-3. [CrossRef]

- Ren C, Sun J, Kong L, Wang H. Breast surgery for patients with de novo metastatic breast cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2024;50(1):107308. [CrossRef]

- Fitzal F, Bjelic-Radisic V, Knauer M, Steger G, Hubalek M, Balic M, et al. Impact of breast surgery in primary metastasized breast cancer: outcomes of the prospective randomized phase III ABCSG-28 POSYTIVE trial. Annals of surgery. 2019;269(6):1163-9.

- Tohme S, Simmons RL, Tsung A. Surgery for cancer: a trigger for metastases. Cancer research. 2017;77(7):1548-52. [CrossRef]

- Castano Z, San Juan BP, Spiegel A, Pant A, DeCristo MJ, Laszewski T, et al. IL-1β inflammatory response driven by primary breast cancer prevents metastasis-initiating cell colonization. Nature cell biology. 2018;20(9):1084-97. [CrossRef]

- Tosello G, Torloni MR, Mota BS, Neeman T, Riera R. Breast surgery for metastatic breast cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018(3).

- Reinhorn D, Mutai R, Yerushalmi R, Moore A, Amir E, Goldvaser H. Locoregional therapy in de novo metastatic breast cancer: systemic review and meta-analysis. The Breast. 2021;58:173-81. [CrossRef]

- Kommalapati A, Tella SH, Goyal G, Ganti AK, Krishnamurthy J, Tandra PK. A prognostic scoring model for survival after locoregional therapy in de novo stage IV breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2018;170(3):677-85. [CrossRef]

- Bai J, Li Z, Guo J, Gao F, Zhou H, Zhao W, et al. Development of a predictive model to identify patients most likely to benefit from surgery in metastatic breast cancer. Scientific Reports. 2023;13(1):3845. [CrossRef]

- Verghis N SC, Soran A, editor The applicability of two survival nomograms for surgery in bone-only de novo stage IV breast cancer. The 26th 2025 American Society of Breast Surgeons Annual Meeting; 2025; The Bellagio Las Vegas.

- Goktepe B, Demirors B, Senol K, Ozbas S, Sezgin E, Lucci A, et al. A Pragmatic Grouping Model for Bone-Only De Novo Metastatic Breast Cancer (MetS Protocol MF22-03). Cancers. 2025;17(12):2033. [CrossRef]

| ST group N=372 (%) |

LRT group N=372 (%) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median follow-up (25%,75%) | 39 (26, 58) | 58 (38, 74) | < 0.001 |

| Median age (25%,75%) | 55 (44, 66) | 50 (42, 60) | 0.0001 |

| Median Body mass index (25%,75%) | 28 (25, 31) | 27 (25, 31) | 0.39 |

| Locoregional progression | 76 (20) | 32 (9) | 0.0001 |

| Systemic progression | 244 (66) | 152 (41) | < 0.001 |

| Mortality rate | 217 (58) | 120 (32) | < 0.001 |

| Number of metastases | < 0.001 | ||

| Solitary | 89 (24) | 185 (50) | |

| Multiple (>1) | 283 (76) | 187 (50) | |

| Tumor size | 0.009 | ||

| T1 | 66 (18) | 60 (16) | |

| T2 | 246 (66) | 219 (59) | |

| T3 | 47 (13) | 84 (23) | |

| T4 | 11 (3) | 9 (2) | |

| Tumor type | 0.0005 | ||

| Invasive Ductal Carcinoma | 286 (77) | 313 (84) | |

| Invasive Lobular Carcinoma | 58 (16) | 25 (7) | |

| Others | 27 (7) | 34 (9) | |

| Histologic grade | 0.02 | ||

| 1 | 52 (14) | 32 (9) | |

| 2 | 162 (45) | 188 (51) | |

| 3 | 129 (36) | 140 (38) | |

| Missing | 16 (4) | 8 (2) | |

| Her2 status | 0.36 | ||

| Negative | 279 (75) | 268 (72) | |

| Positive | 93 (25) | 104 (28) | |

| Estrogen/Progesterone receptors | 0.04 | ||

| Negative | 41 (11) | 60 (16) | |

| Positive | 331 (89) | 312 (84) | |

| Triple Negative | 0.28 | ||

| No | 353 (95) | 346 (93) | |

| Yes | 19 (5) | 26 (7) | |

| Hormonotherapy | 317 (85) | 317 (85) | 0.99 |

| Chemotherapy | 322 (87) | 353 (95) | 0.0005 |

| Bisphosphonate treatment | 260 (70) | 231 (62) | 0.02 |

| Ovarian suppression | 71 (19) | 88 (24) | 0.13 |

| Intervention to metastasis | 188 (51) | 198 (53) | 0.46 |

| ST group N=372 (%) |

LRT+ST group N=221 (%) |

ST+LRT group N=151 (%) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median follow-up (25%,75%) | 39 (26, 58) | 59 (40, 74) | 53 (38, 73) | < 0.001 |

| Median age (25%,75%) | 55 (44, 66) | 50 (43, 59) | 49 (40, 60) | 0.0001 |

| Median BMI (25%,75%) | 28 (25, 31) | 27 (24, 31) | 27 (25, 31) | 0.69 |

| Locoregional progression | 76 (20) | 23 (10) | 9 (6) | 0.0001 |

| Systemic progression | 244 (66) | 87 (39) | 65 (43) | < 0.001 |

| Mortality rate | 217 (58) | 76 (34) | 44 (29) | < 0.001 |

| Number of metastases | < 0.001 | |||

| Solitary | 89 (24) | 125 (57) | 60 (40) | |

| Multiple (>1) | 283 (76) | 96 (43) | 91 (60) | |

| Tumor size | 0.008 | |||

| T1 | 66 (18) | 42 (19) | 18 (12) | |

| T2 | 246 (66) | 132 (60) | 87 (58) | |

| T3 | 47 (13) | 44 (20) | 40 (26) | |

| T4 | 11 (3) | 3 (1) | 6 (4) | |

| Tumor type | 0.002 | |||

| Invasive Ductal Carcinoma | 286 (77) | 186 (84) | 127 (84) | |

| Invasive Lobular Carcinoma | 58 (16) | 12 (5) | 13 (9) | |

| Others | 27 (7) | 23 (10) | 11 (7) | |

| Histologic grade | 0.036 | |||

| 1 | 52 (14) | 18 (8) | 14 (10) | |

| 2 | 162 (45) | 111 (50) | 77 (52) | |

| 3 | 129 (36) | 84 (38) | 56 (38) | |

| Missing | 16 (4) | 8 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Her2 status | 0.40 | |||

| Negative | 279 (75) | 155 (70) | 113 (75) | |

| Positive | 93 (25) | 66 (30) | 38 (25) | |

| Estrogen/Progesterone receptors | 0.05 | |||

| Negative | 41 (11) | 40 (18) | 20 (13) | |

| Positive | 331 (89) | 181 (82) | 131 (87) | |

| Triple negative | 0.07 | |||

| No | 353 (95) | 201 (91) | 145 (96) | |

| Yes | 19 (5) | 20 (9) | 6 (4) | |

| Hormonotherapy | 317 (85) | 182 (82) | 135 (89) | 0.17 |

| Chemotherapy | 322 (87) | 205 (93) | 148 (98) | 0.0002 |

| Bisphosphonate treatment | 260 (70) | 149 (67) | 82 (54) | 0.003 |

| Ovarian suppression | 71 (19) | 49 (22) | 39 (26) | 0.22 |

| Intervention to metastasis | 188 (51) | 99 (45) | 99 (66) | 0.0003 |

| Parameter | HR (95%CI) | P | HRadj (95%CI) | Padj |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locoregional therapy | 0.35 (0.29-0.45) | <0.0001 | 0.49 (0.38-0.63) | <0.0001 |

| Age > 52 (median age) | 1.30 (1.05-1.62) | 0.02 | 1.29 (1.02-1.61) | 0.03 |

| Locoregional progression | 1.92 (1.48-2.49) | <0.0001 | 1.18 (0.89-1.55) | 0.25 |

| Systemic progression | 5.89 (4.38-7.93) | <0.0001 | 4.84 (3.55-6.63) | <0.0001 |

| Number of metastases | 1.59 (1.26-1.99) | <0.0001 | 1.21 (0.96-1.54) | 0.11 |

| Primary tumor size | 1.09 (0.93-1.28) | 0.28 | 1.06 (0.89-1.27) | 0.51 |

| Tumor type | 1.02 (0.85-1.22) | 0.85 | 0.93 (0.77-1.13) | 0.48 |

| Histologic grade | 1.01 (0.87-1.18) | 0.88 | 0.97 (0.83-1.14) | 0.71 |

| ER/PR (+) | 0.74 (0.56-0.98) | 0.04 | 0.62 (0.46-0.84) | 0.002 |

| Chemotherapy received | 0.83 (0.56-1.22) | 0.33 | 1.30 (0.81-2.09) | 0.27 |

| Bisphosphonate treatment received | 1.08 (0.85-1.37) | 0.54 | 1.00 (0.77-1.30) | 0.98 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).