Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Topic Presentation

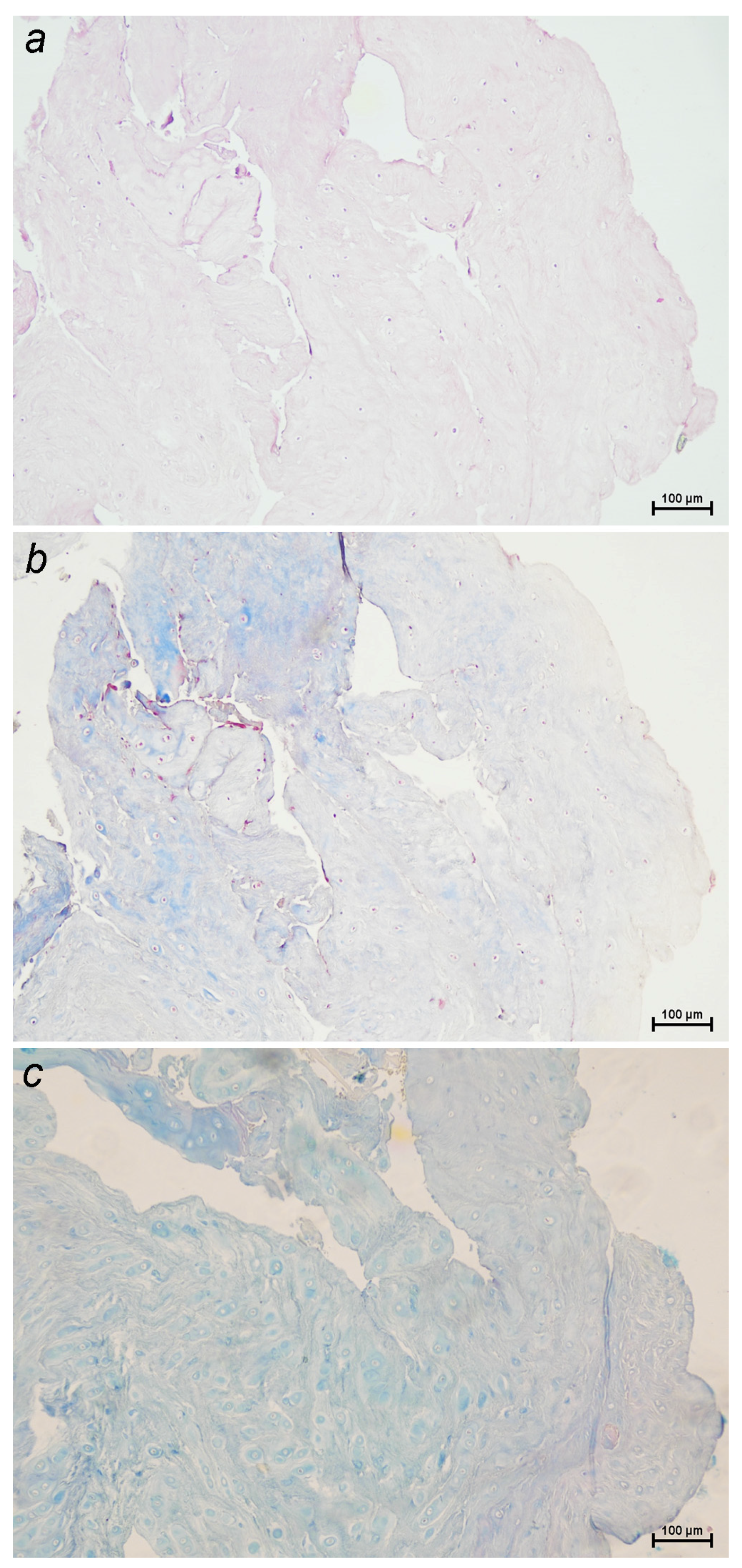

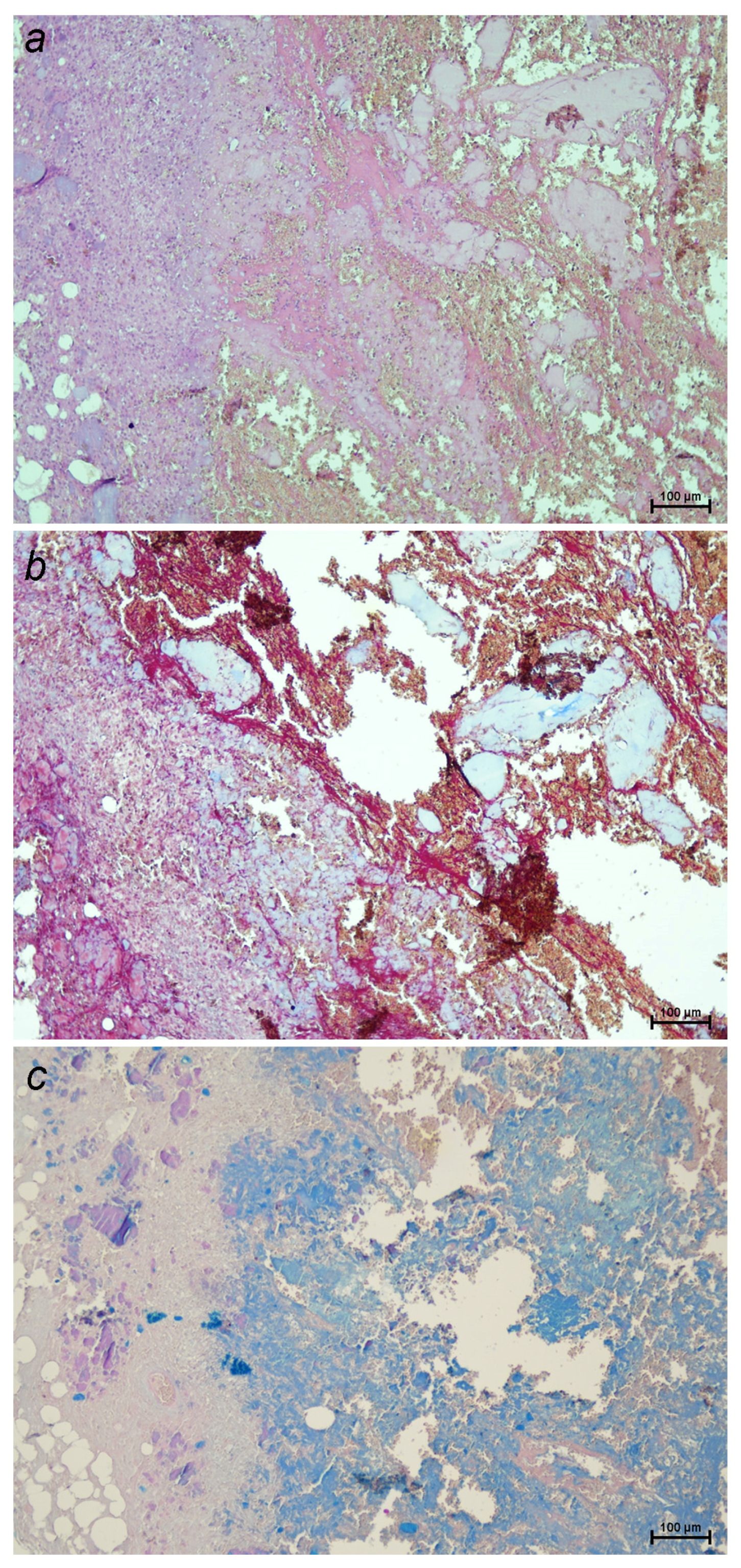

2.1. Pathophysiology

2.2. Clinical Presentation

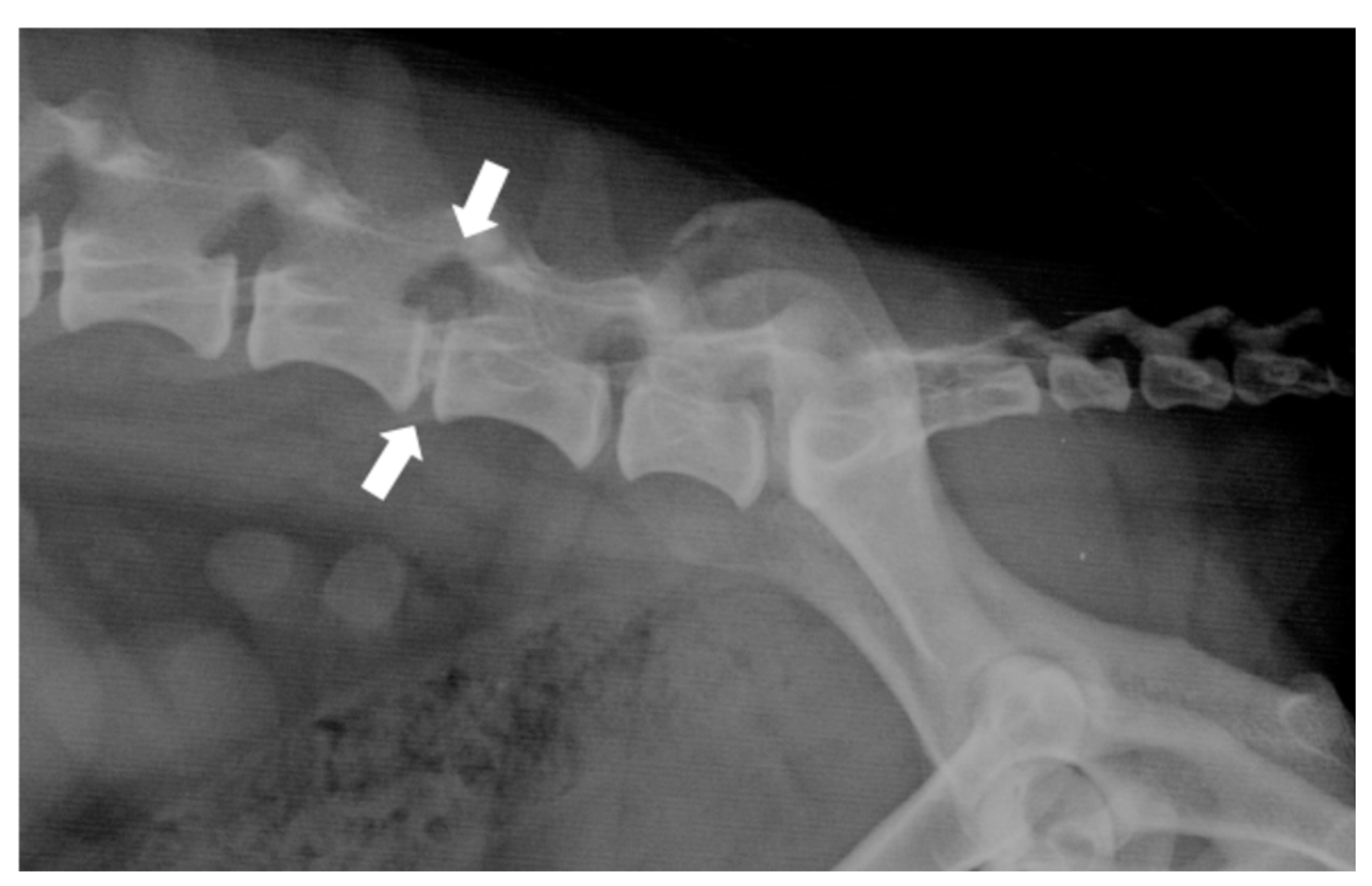

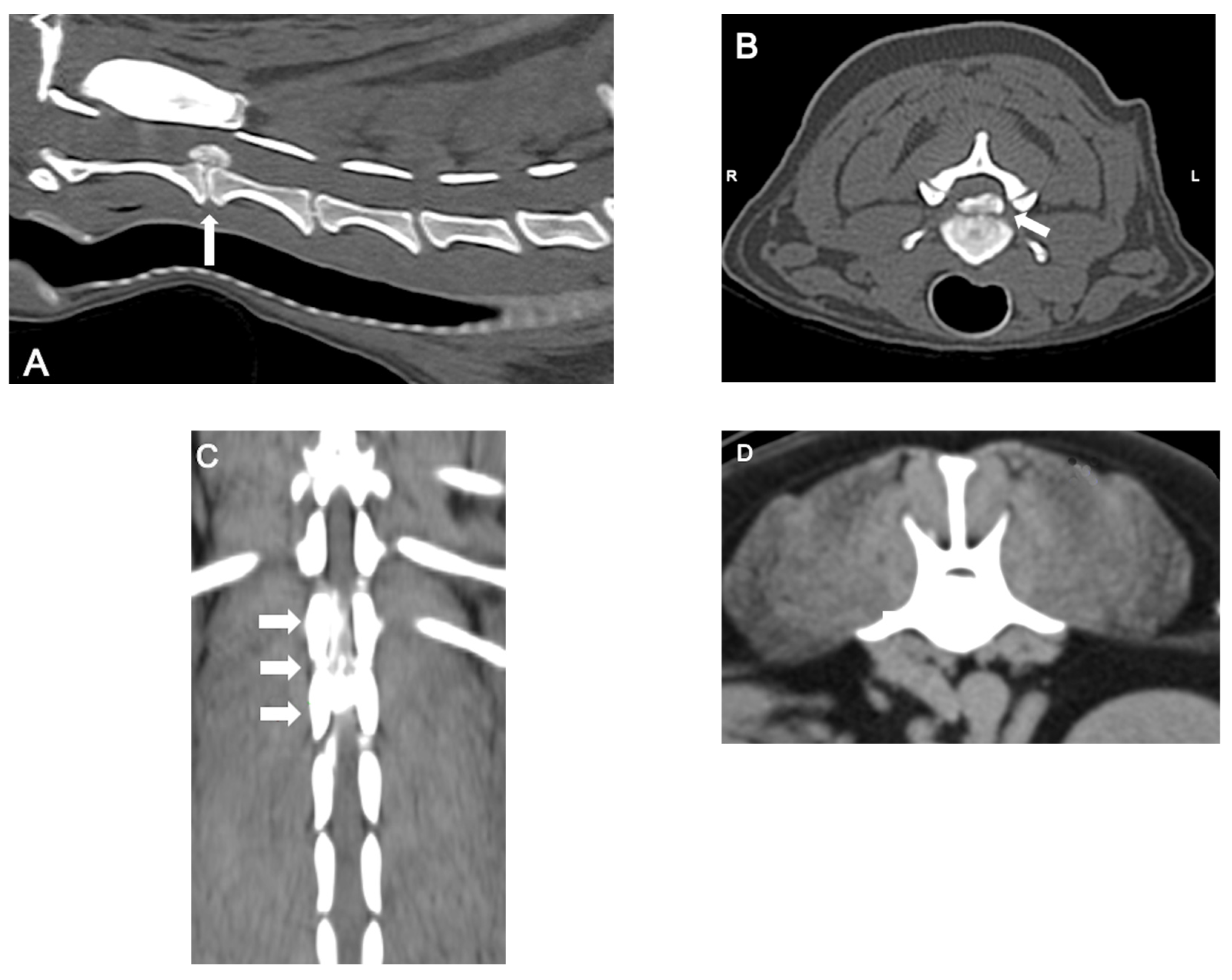

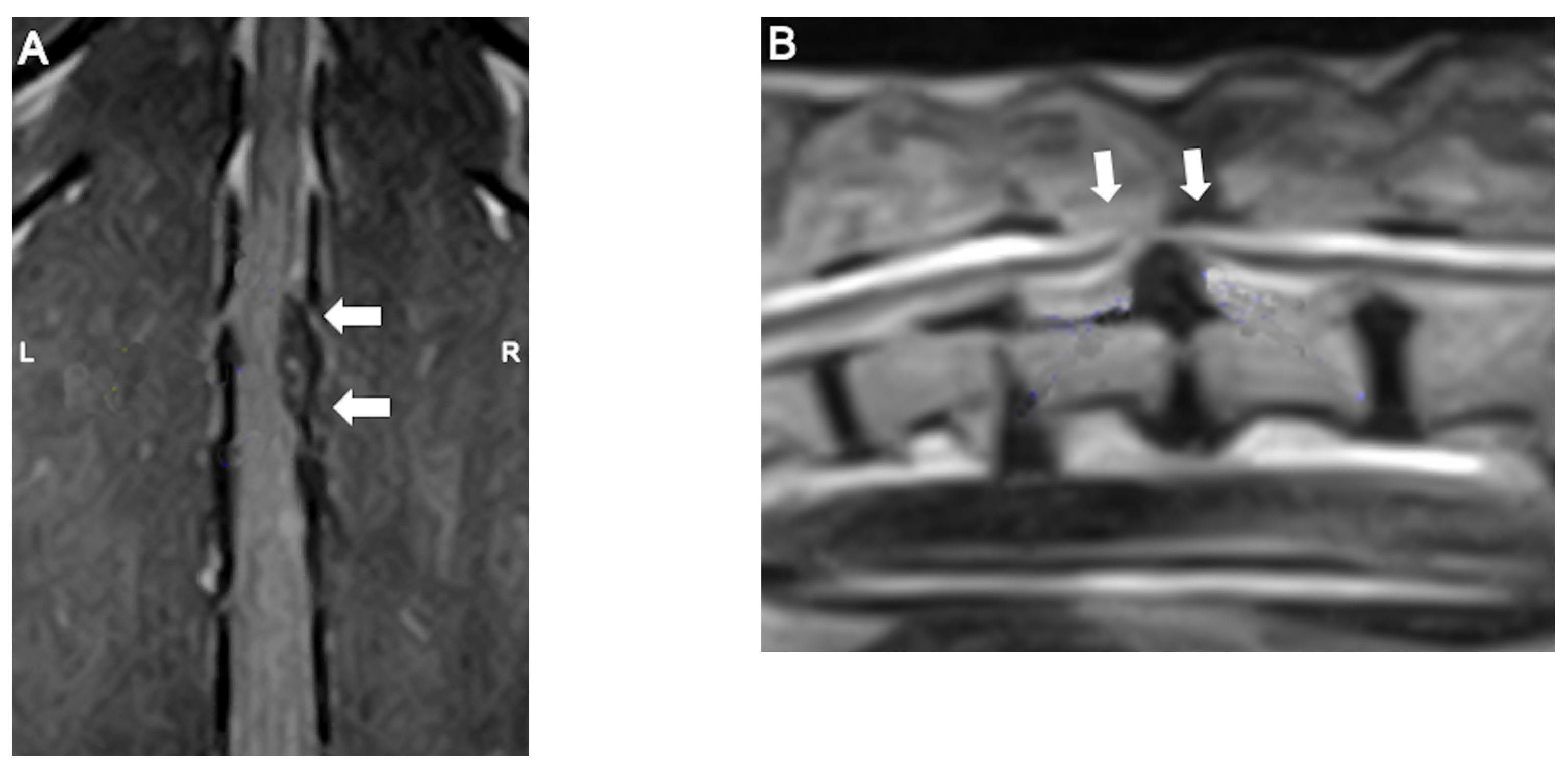

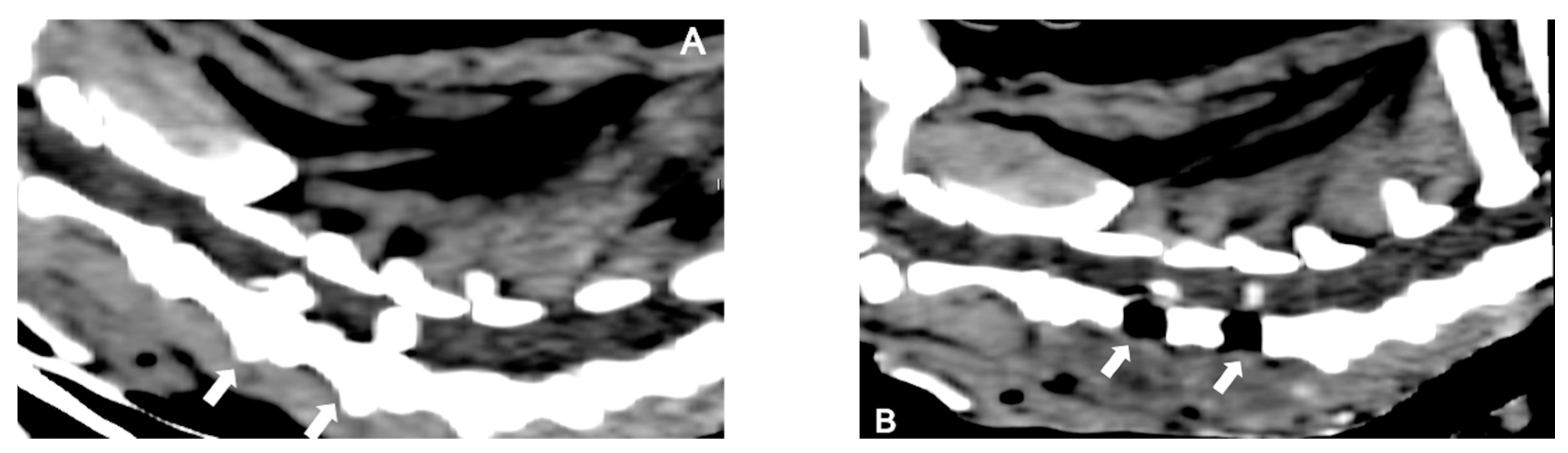

2.3. Diagnosis

2.4. Treatment

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brisson, B. A. (2010). Intervertebral disc disease in dogs. The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Small Animal Practice, 40(5), 829–858. [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J. F., Levine, J., Kerwin, S., & Cole, R. (2009). Canine thoracolumbar invertebral disk disease: Diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Compendium (Yardley, PA), 31(3), E3.

- Brown, E. A., Dickinson, P. J., Mansour, T., Sturges, B. K., Aguilar, M., Young, A. E., Korff, C., Lind, J., Ettinger, C. L., Varon, S., Pollard, R., Brown, C. T., Raudsepp, T., & Bannasch, D. L. (2017). FGF4 retrogene on CFA12 is responsible for chondrodystrophy and intervertebral disc disease in dogs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(43), 11476–11481. [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, P. J., & Bannasch, D. L. (2020). Current Understanding of the Genetics of Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7, 431. [CrossRef]

- Fenn, J., Olby, N. J., & Canine Spinal Cord Injury Consortium (CANSORT-SCI). (2020). Classification of Intervertebral Disc Disease. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7, 579025. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, H. J. (1951). A pathologic-anatomical interpretation of disc degeneration in dogs. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica, 20(4), 280–293. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, H. J. (1952). A pathologic-anatomical study on disc degeneration in dog, with special reference to the so-called enchondrosis intervertebralis. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica. Supplementum, 11, 1–117. [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, N. D., Levine, J. M., Olby, N. J., & Stein, V. M. (2013). Intervertebral disk degeneration in dogs: Consequences, diagnosis, treatment, and future directions. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 27(6), 1318–1333. [CrossRef]

- da Costa, R. C., & Samii, V. F. (2010). Advanced imaging of the spine in small animals. The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Small Animal Practice, 40(5), 765–790. [CrossRef]

- Bergknut, N., Smolders, L. A., Grinwis, G. C. M., Hagman, R., Lagerstedt, A.-S., Hazewinkel, H. A. W., Tryfonidou, M. A., & Meij, B. P. (2013). Intervertebral disc degeneration in the dog. Part 1: Anatomy and physiology of the intervertebral disc and characteristics of intervertebral disc degeneration. Veterinary Journal (London, England: 1997), 195(3), 282–291. [CrossRef]

- Bergknut, N., Meij, B. P., Hagman, R., de Nies, K. S., Rutges, J. P., Smolders, L. A., Creemers, L. B., Lagerstedt, A. S., Hazewinkel, H. a. W., & Grinwis, G. C. M. (2013). Intervertebral disc disease in dogs - part 1: A new histological grading scheme for classification of intervertebral disc degeneration in dogs. Veterinary Journal (London, England: 1997), 195(2), 156–163. [CrossRef]

- Kranenburg, H.-J. C., Grinwis, G. C. M., Bergknut, N., Gahrmann, N., Voorhout, G., Hazewinkel, H. A. W., & Meij, B. P. (2013). Intervertebral disc disease in dogs - part 2: Comparison of clinical, magnetic resonance imaging, and histological findings in 74 surgically treated dogs. Veterinary Journal (London, England: 1997), 195(2), 164–171. [CrossRef]

- Niemeyer, F., Galbusera, F., Beukers, M., Jonas, R., Tao, Y., Fusellier, M., Tryfonidou, M. A., Neidlinger-Wilke, C., Kienle, A., & Wilke, H.-J. (2024). Automatic grading of intervertebral disc degeneration in lumbar dog spines. JOR Spine, 7(2), e1326. [CrossRef]

- Bergknut, N., Auriemma, E., Wijsman, S., Voorhout, G., Hagman, R., Lagerstedt, A.-S., Hazewinkel, H. A. W., & Meij, B. P. (2011). Evaluation of intervertebral disk degeneration in chondrodystrophic and nonchondrodystrophic dogs by use of Pfirrmann grading of images obtained with low-field magnetic resonance imaging. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 72(7), 893–898. [CrossRef]

- Harder, L., Ludwig, D., Galindo-Zamora, V., Wefstaedt, P., & Nolte, I. (2014). [Classification of canine intervertebral disc degeneration using high-field magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography]. Tierarztliche Praxis. Ausgabe K, Kleintiere/Heimtiere, 42(6), 374–382. [CrossRef]

- Smolders, L. A., Bergknut, N., Grinwis, G. C. M., Hagman, R., Lagerstedt, A.-S., Hazewinkel, H. A. W., Tryfonidou, M. A., & Meij, B. P. (2013). Intervertebral disc degeneration in the dog. Part 2: Chondrodystrophic and non-chondrodystrophic breeds. Veterinary Journal (London, England: 1997), 195(3), 292–299. [CrossRef]

- Willems, N., Tellegen, A. R., Bergknut, N., Creemers, L. B., Wolfswinkel, J., Freudigmann, C., Benz, K., Grinwis, G. C. M., Tryfonidou, M. A., & Meij, B. P. (2016). Inflammatory profiles in canine intervertebral disc degeneration. BMC Veterinary Research, 12, 10. [CrossRef]

- Pilkington, E. J., De Decker, S., Skovola, E., Cloquell Miro, A., Gutierrez Quintana, R., Faller, K. M. E., Aguilera Padros, A., & Goncalves, R. (2024). Prevalence, clinical presentation, and etiology of myelopathies in 224 juvenile dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 38(3), 1598–1607. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G., Stachel, A., Lynch, A. M., & Olby, N. J. (2020). Intervertebral disc disease and aortic thromboembolism are the most common causes of acute paralysis in dogs and cats presenting to an emergency clinic. The Veterinary Record, 187(10), e81. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T., Smolders, L. A., Tryfonidou, M. A., Meij, B. P., Vernooij, J. C. M., Bergknut, N., & Grinwis, G. C. M. (2017). The Myth of Fibroid Degeneration in the Canine Intervertebral Disc: A Histopathological Comparison of Intervertebral Disc Degeneration in Chondrodystrophic and Nonchondrodystrophic Dogs. Veterinary Pathology, 54(6), 945–952. [CrossRef]

- Doeven, L., Cardy, T., & Crawford, A. H. (2024). Investigation of neutering status and age of neutering in female Dachshunds with thoracolumbar intervertebral disc extrusion. The Journal of Small Animal Practice, 65(8), 637–641. [CrossRef]

- Suiter, E., Grapes, N., Martin-Garcia, L., De Decker, S., Gutierrez-Quintana, R., & Wessmann, A. (2023). MRI and clinical findings in 133 dogs with recurrent deficits following intervertebral disc extrusion surgery. The Veterinary Record, 193(5), e2992. [CrossRef]

- Mateo, I., Lorenzo, V., Foradada, L., & Muñoz, A. (2011). Clinical, Pathologic, and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Characteristics of Canine Disc Extrusion Accompanied by Epidural Hemorrhage or Inflammation. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound, 52(1), 17–24. [CrossRef]

- Levine, G. J., Levine, J. M., Budke, C. M., Kerwin, S. C., Au, J., Vinayak, A., Hettlich, B. F., & Slater, M. R. (2009). Description and repeatability of a newly developed spinal cord injury scale for dogs. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 89(1–2), 121–127. [CrossRef]

- Aikawa, T., Miyazaki, Y., Kihara, S., Muyama, H., & Nishimura, M. (2024). Cervical intervertebral disc disease in 307 small-breed dogs (2000-2021): Breed-characteristic features and disc-associated vertebral instability. Australian Veterinary Journal, 102(5), 274–281. [CrossRef]

- Bersan, E., McConnell, F., Trevail, R., Behr, S., De Decker, S., Volk, H. A., Smith, P. M., & Gonçalves, R. (2015). Cervical intervertebral foraminal disc extrusion in dogs: Clinical presentation, MRI characteristics and outcome after medical management. The Veterinary Record, 176(23), 597. [CrossRef]

- Olender, M., Couturier, J., Gatel, L., & Cauvin, E. (2023). Cervical jerks as a sign of cervical pain or myelopathy in dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 261(4), 510–516. [CrossRef]

- Schachar, J., Bocage, A., Nelson, N. C., Early, P. J., Mariani, C. L., Olby, N. J., & Muñana, K. R. (2024). Clinical and imaging findings in dogs with nerve root signature associated with cervical intervertebral disc herniation. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 38(2), 1111–1119. [CrossRef]

- Crawford, A. H., & De Decker, S. (2017). Clinical presentation and outcome of dogs treated medically or surgically for thoracolumbar intervertebral disc protrusion. The Veterinary Record, 180(23), 569. [CrossRef]

- Alcoverro, E., Schofield, I., Spinillo, S., Tauro, A., Ruggeri, M., Lowrie, M., & Gomes, S. A. (2024). Thoracolumbar hydrated nucleus pulposus extrusion and intervertebral disc extrusion in dogs: Comparison of clinical presentation and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Veterinary Journal (London, England: 1997), 306, 106178. [CrossRef]

- Silva, S., Guevar, J., José-López, R., De Decker, S., Brocal, J., de la Fuente, C., Durand, A., Forterre, F., Olby, N., & Gutierrez-Quintana, R. (2022). Clinical signs, MRI findings and long-term outcomes of foraminal and far lateral thoracolumbar intervertebral disc herniations in dogs. The Veterinary Record, 190(12), e1529. [CrossRef]

- Aikawa, T., Shibata, M., Asano, M., Hara, Y., Tagawa, M., & Orima, H. (2014). A comparison of thoracolumbar intervertebral disc extrusion in French Bulldogs and Dachshunds and association with congenital vertebral anomalies. Veterinary Surgery: VS, 43(3), 301–307. [CrossRef]

- Poli, F., Calistri, M., Meucci, V., DI Gennaro, G., & Baroni, M. (2022). Prevalence, clinical features, and outcome of intervertebral disc extrusion associated with extensive epidural hemorrhage in a population of French Bulldogs compared to Dachshunds. The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science, 84(9), 1307–1312. [CrossRef]

- Parry, A. T., Harris, A., Upjohn, M. M., Chandler, K., & Lamb, C. R. (2010). Does choice of imaging modality affect outcome in dogs with thoracolumbar spinal conditions? The Journal of Small Animal Practice, 51(6), 312–317. [CrossRef]

- Harder, L. K. (2016). [Diagnostic imaging of changes of the canine intervertebral disc]. Tierarztliche Praxis. Ausgabe K, Kleintiere/Heimtiere, 44(5), 359–371. [CrossRef]

- da Costa, R. C., De Decker, S., Lewis, M. J., Volk, H., & Canine Spinal Cord Injury Consortium (CANSORT-SCI). (2020). Diagnostic Imaging in Intervertebral Disc Disease. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7, 588338. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, I., & Thrall, D. E. (2011). Imaging dogs with suspected disc herniation: Pros and cons of myelography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound: The Official Journal of the American College of Veterinary Radiology and the International Veterinary Radiology Association, 52(1 Suppl 1), S81-84. [CrossRef]

- Dennison, S. E., Drees, R., Rylander, H., Yandell, B. S., Milovancev, M., Pettigrew, R., & Schwarz, T. (2010). Evaluation of different computed tomography techniques and myelography for the diagnosis of acute canine myelopathy. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound: The Official Journal of the American College of Veterinary Radiology and the International Veterinary Radiology Association, 51(3), 254–258. [CrossRef]

- Srugo, I., Aroch, I., Christopher, M. M., Chai, O., Goralnik, L., Bdolah-Abram, T., & Shamir, M. H. (2011). Association of cerebrospinal fluid analysis findings with clinical signs and outcome in acute nonambulatory thoracolumbar disc disease in dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 25(4), 846–855. [CrossRef]

- Emery, L., Hecht, S., & Sun, X. (2018). Investigation of parameters predicting the need for diagnostic imaging beyond computed tomography in the evaluation of dogs with thoracolumbar myelopathy: Retrospective evaluation of 555 dogs. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound: The Official Journal of the American College of Veterinary Radiology and the International Veterinary Radiology Association, 59(2), 147–154. [CrossRef]

- Noyes, J. A., Thomovsky, S. A., Chen, A. V., Owen, T. J., Fransson, B. A., Carbonneau, K. J., & Matthew, S. M. (2017). Magnetic resonance imaging versus computed tomography to plan hemilaminectomies in chondrodystrophic dogs with intervertebral disc extrusion. Veterinary Surgery: VS, 46(7), 1025–1031. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J. J., Young, B. D., Griffin, J. F., Fosgate, G. T., & Levine, J. M. (2014). Comparison between noncontrast computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for detection and characterization of thoracolumbar myelopathy caused by intervertebral disk herniation in dogs. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound: The Official Journal of the American College of Veterinary Radiology and the International Veterinary Radiology Association, 55(2), 182–189. [CrossRef]

- Olby, N. J., Moore, S. A., Brisson, B., Fenn, J., Flegel, T., Kortz, G., Lewis, M., & Tipold, A. (2022). ACVIM consensus statement on diagnosis and management of acute canine thoracolumbar intervertebral disc extrusion. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 36(5), 1570–1596. [CrossRef]

- Moore, S. A., Early, P. J., & Hettlich, B. F. (2016). Practice patterns in the management of acute intervertebral disc herniation in dogs. The Journal of Small Animal Practice, 57(8), 409–415. [CrossRef]

- Moore, S. A., Tipold, A., Olby, N. J., Stein, V., Granger, N., & Canine Spinal Cord Injury Consortium (CANSORT SCI). (2020). Current Approaches to the Management of Acute Thoracolumbar Disc Extrusion in Dogs. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7, 610. [CrossRef]

- Langerhuus, L., & Miles, J. (2017). Proportion recovery and times to ambulation for non-ambulatory dogs with thoracolumbar disc extrusions treated with hemilaminectomy or conservative treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of case-series studies. Veterinary Journal (London, England: 1997), 220, 7–16. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M. J., Jeffery, N. D., Olby, N. J., & Canine Spinal Cord Injury Consortium (CANSORT-SCI). (2020). Ambulation in Dogs With Absent Pain Perception After Acute Thoracolumbar Spinal Cord Injury. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7, 560. [CrossRef]

- Klesty, A., Forterre, F., & Bolln, G. (2019). [Outcome of intervertebral disk disease surgery depending on dog breed, location and experience of the surgeon: 1113 cases]. Tierarztliche Praxis. Ausgabe K, Kleintiere/Heimtiere, 47(4), 233–241. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S., Jeffery, N. D., & Freeman, P. (2024). Recovery of ambulation in small, nonbrachycephalic dogs after conservative management of acute thoracolumbar disk extrusion. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 38(5), 2603–2611. [CrossRef]

- Skytte, D., & Schmökel, H. (2018). Relationship of preoperative neurologic score with intervals to regaining micturition and ambulation following surgical treatment of thoracolumbar disk herniation in dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 253(2), 196–200. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, F., Honnami, A., Toki, M., Dosaka, A., Fujita, Y., Hara, Y., & Yamaguchi, S. (2020). Effect of durotomy in dogs with thoracolumbar disc herniation and without deep pain perception in the hind limbs. Veterinary Surgery: VS, 49(5), 860–869. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A. J. A., Correia, J. H. D., & Jaggy, A. (2002). Thoracolumbar disc disease in 71 paraplegic dogs: Influence of rate of onset and duration of clinical signs on treatment results. The Journal of Small Animal Practice, 43(4), 158–163. [CrossRef]

- Immekeppel, A., Rupp, S., Demierre, S., Rentmeister, K., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., Goessmann, J., Bali, M. S., Schmidli-Davies, F., & Forterre, F. (2021). Investigation of timing of surgery and other factors possibly influencing outcome in dogs with acute thoracolumbar disc extrusion: A retrospective study of 1501 cases. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica, 63(1), 30. [CrossRef]

- Martin, S., Liebel, F. X., Fadda, A., Lazzerini, K., & Harcourt-Brown, T. (2020). Same-day surgery may reduce the risk of losing pain perception in dogs with thoracolumbar disc extrusion. The Journal of Small Animal Practice, 61(7), 442–448. [CrossRef]

- Upchurch, D. A., Renberg, W. C., Turner, H. S., & McLellan, J. G. (2020). Effect of Duration and Onset of Clinical Signs on Short-Term Outcome of Dogs with Hansen Type I Thoracolumbar Intervertebral Disc Extrusion. Veterinary and Comparative Orthopaedics and Traumatology: V.C.O.T, 33(3), 161–166. [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, N. D., & Freeman, P. M. (2018). The Role of Fenestration in Management of Type I Thoracolumbar Disk Degeneration. The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Small Animal Practice, 48(1), 187–200. [CrossRef]

- Aikawa, T., Fujita, H., Shibata, M., & Takahashi, T. (2012). Recurrent thoracolumbar intervertebral disc extrusion after hemilaminectomy and concomitant prophylactic fenestration in 662 chondrodystrophic dogs. Veterinary Surgery: VS, 41(3), 381–390. [CrossRef]

- Aikawa, T., Fujita, H., Kanazono, S., Shibata, M., & Yoshigae, Y. (2012). Long-term neurologic outcome of hemilaminectomy and disk fenestration for treatment of dogs with thoracolumbar intervertebral disk herniation: 831 cases (2000-2007). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 241(12), 1617–1626. [CrossRef]

- Brisson, B. A., Holmberg, D. L., Parent, J., Sears, W. C., & Wick, S. E. (2011). Comparison of the effect of single-site and multiple-site disk fenestration on the rate of recurrence of thoracolumbar intervertebral disk herniation in dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 238(12), 1593–1600. [CrossRef]

- Balducci, F., Canal, S., Contiero, B., & Bernardini, M. (2017). Prevalence and Risk Factors for Presumptive Ascending/Descending Myelomalacia in Dogs after Thoracolumbar Intervertebral Disk Herniation. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 31(2), 498–504. [CrossRef]

- Castel, A., Olby, N. J., Ru, H., Mariani, C. L., Muñana, K. R., & Early, P. J. (2019). Risk factors associated with progressive myelomalacia in dogs with complete sensorimotor loss following intervertebral disc extrusion: A retrospective case-control study. BMC Veterinary Research, 15(1), 433. [CrossRef]

- Castel, A., Olby, N. J., Mariani, C. L., Muñana, K. R., & Early, P. J. (2017). Clinical Characteristics of Dogs with Progressive Myelomalacia Following Acute Intervertebral Disc Extrusion. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 31(6), 1782–1789. [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, N. D., Rossmeisl, J. H., Harcourt-Brown, T. R., Granger, N., Ito, D., Foss, K., & Chase, D. (2024). Randomized Controlled Trial of Durotomy as an Adjunct to Routine Decompressive Surgery for Dogs With Severe Acute Spinal Cord Injury. Neurotrauma Reports, 5(1), 128-138. [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, N. D., Barker, A. K., Hu, H. Z., Alcott, C. J., Kraus, K. H., Scanlin, E. M., Granger, N., & Levine, J. M. (2016). Factors associated with recovery from paraplegia in dogs with loss of pain perception in the pelvic limbs following intervertebral disk herniation. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 248(4), 386–394. [CrossRef]

- Mayhew, P. D., McLear, R. C., Ziemer, L. S., Culp, W. T. N., Russell, K. N., Shofer, F. S., Kapatkin, A. S., & Smith, G. K. (2004). Risk factors for recurrence of clinical signs associated with thoracolumbar intervertebral disk herniation in dogs: 229 cases (1994-2000). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 225(8), 1231–1236. [CrossRef]

- Olby, N. J., da Costa, R. C., Levine, J. M., Stein, V. M., & Canine Spinal Cord Injury Consortium (CANSORT SCI). (2020). Prognostic Factors in Canine Acute Intervertebral Disc Disease. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7, 596059. [CrossRef]

- Svensson, G., Simonsson, U. S. H., Danielsson, F., & Schwarz, T. (2017). Residual Spinal Cord Compression Following Hemilaminectomy and Mini-Hemilaminectomy in Dogs: A Prospective Randomized Study. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 4, 42. [CrossRef]

- Wang-Leandro, A., Siedenburg, J. S., Hobert, M. K., Dziallas, P., Rohn, K., Stein, V. M., & Tipold, A. (2017). Comparison of Preoperative Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Clinical Assessment of Deep Pain Perception as Prognostic Tools for Early Recovery of Motor Function in Paraplegic Dogs with Intervertebral Disk Herniations. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 31(3), 842–848. [CrossRef]

- Woelfel, C. W., Robertson, J. B., Mariani, C. L., Muñana, K. R., Early, P. J., & Olby, N. J. (2021). Outcomes and prognostic indicators in 59 paraplegic medium to large breed dogs with extensive epidural hemorrhage secondary to thoracolumbar disc extrusion. Veterinary Surgery: VS, 50(3), 527–536. [CrossRef]

- Guo, S., Lu, D., Pfeiffer, S., & Pfeiffer, D. U. (2020). Non-ambulatory dogs with cervical intervertebral disc herniation: Single versus multiple ventral slot decompression. Australian Veterinary Journal, 98(4), 148–155. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M. J., Granger, N., Jeffery, N. D., & Canine Spinal Cord Injury Consortium (CANSORT-SCI). (2020). Emerging and Adjunctive Therapies for Spinal Cord Injury Following Acute Canine Intervertebral Disc Herniation. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7, 579933. [CrossRef]

- Prager, J., Fenn, J., Plested, M., Escauriaza, L., Merwe, T. van der, King, B., Chari, D., Wong, L.-F., & Granger, N. (2022). Transplantation of encapsulated autologous olfactory ensheathing cell populations expressing chondroitinase for spinal cord injury: A safety and feasibility study in companion dogs. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine, 16(9), 788–798. [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, M. M., Bevan, J. M., Evans, R. B., & Johnson, T. I. (2017). Influence of in-house rehabilitation on the postoperative outcome of dogs with intervertebral disk herniation. Veterinary Surgery: VS, 46(4), 566–573. [CrossRef]

| Grade 1 | Spinal hyperaesthesia |

| Grade 2 | Ambulatory paraparesis |

| Grade 3 | Non-ambulatory paraparesis |

| Grade 4 | Paraplegic with intact pain sensation |

| Grade 5 | Paraplegic with absent deep pain sensation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).