Submitted:

07 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Experimental Design and Treatments

2.3. Experiment Management

2.4. Microclimate

2.5. Morphometric Variables

2.6. Physiological Variables

2.6.1. Leaf Water Potential

2.6.2. Gas Exchange

2.6.3. Leaf Area Index Measurement

2.7. Chlorophyll Content

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

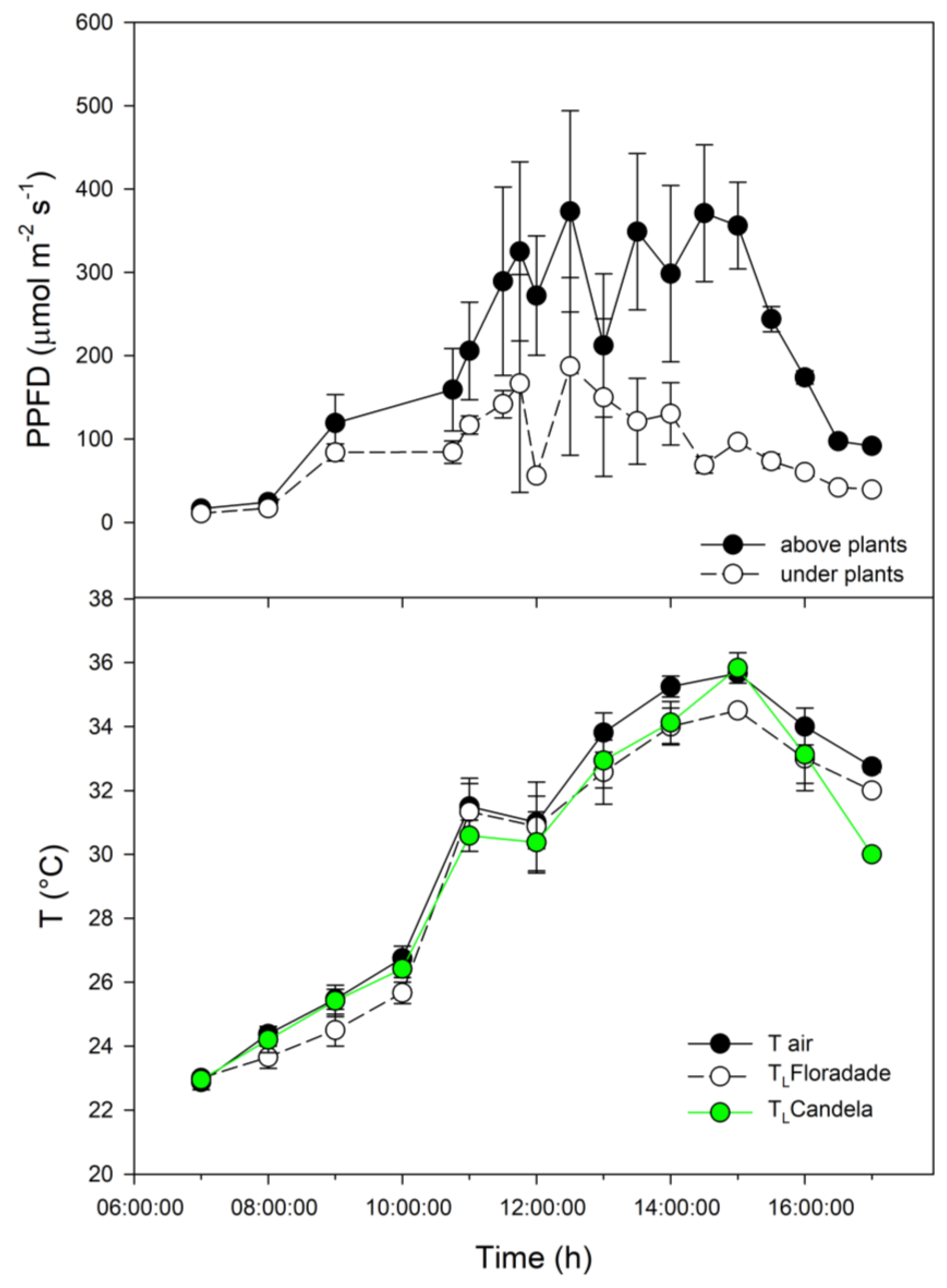

3.1. Microclimate

3.2. Morphometric Variables

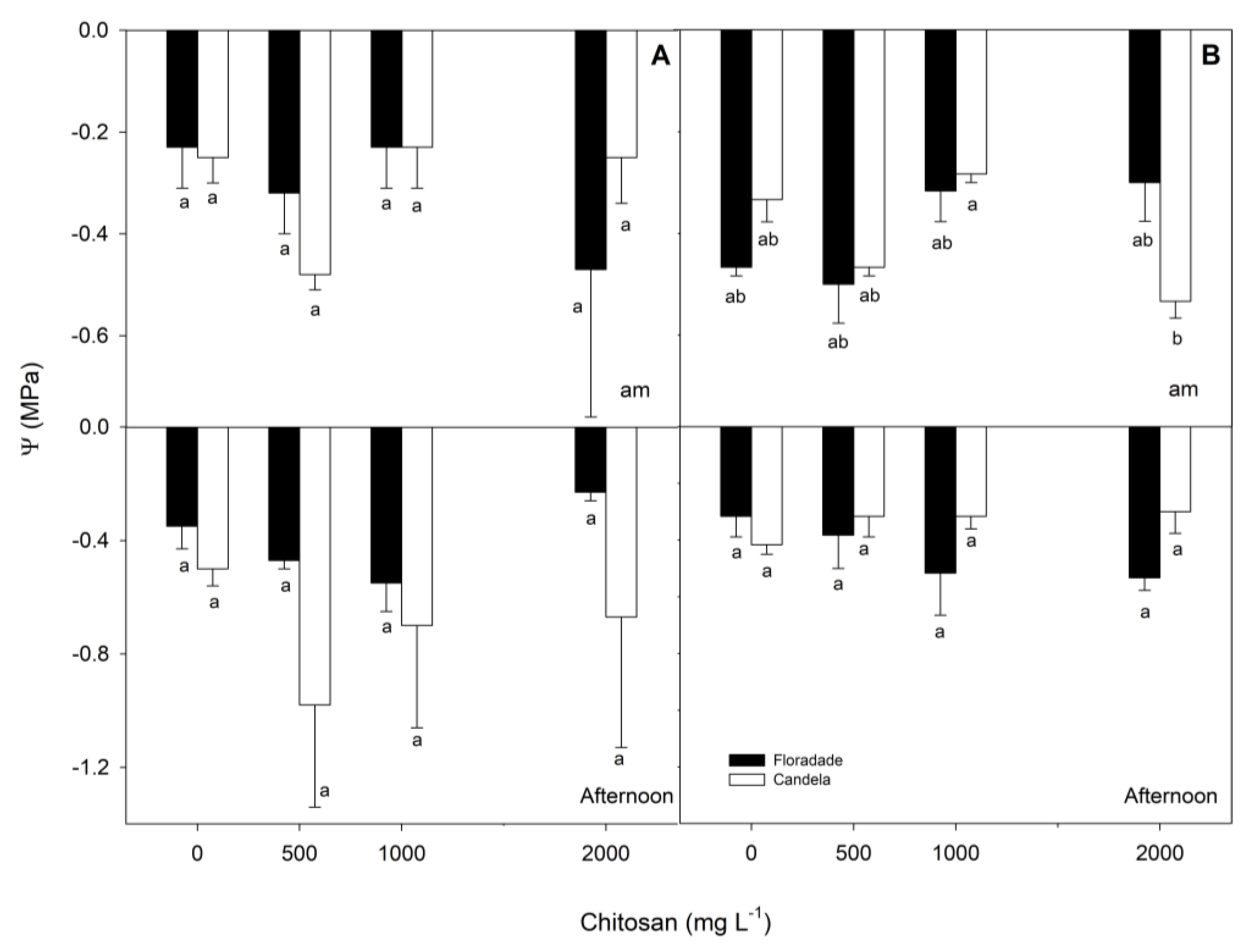

3.3. Water Potential

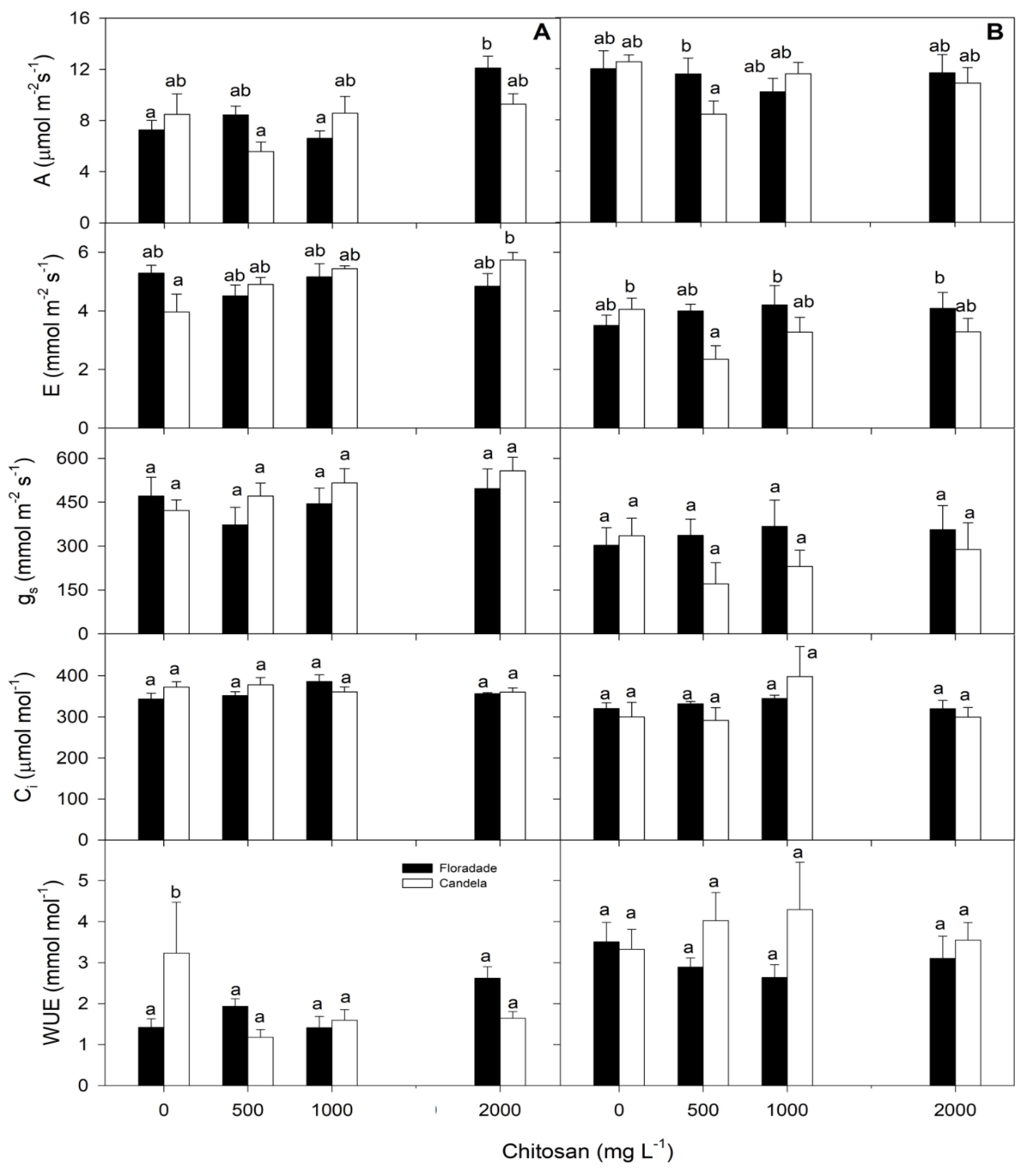

3.4. Gas Exchange

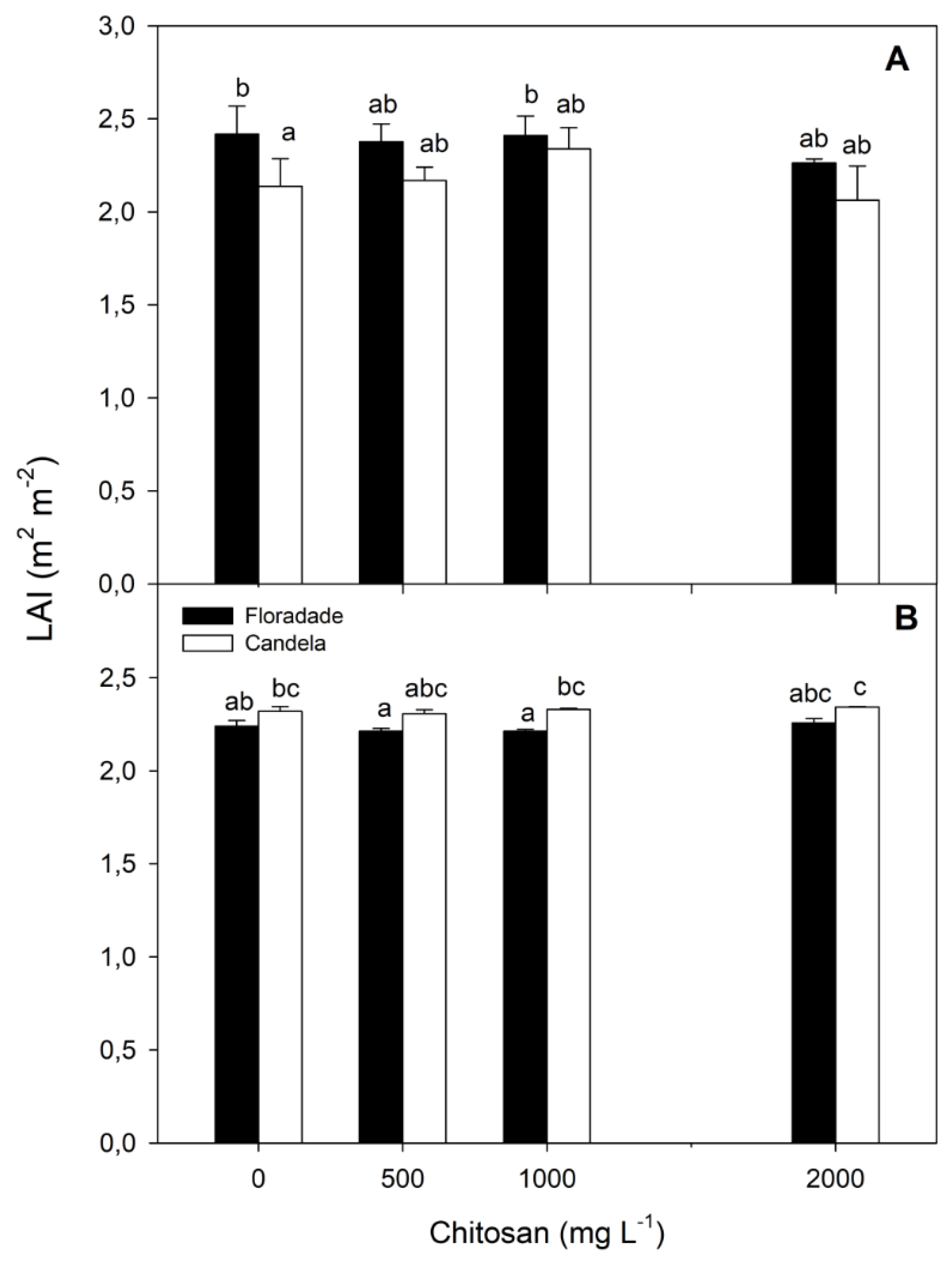

3.5. Leaf Area Index

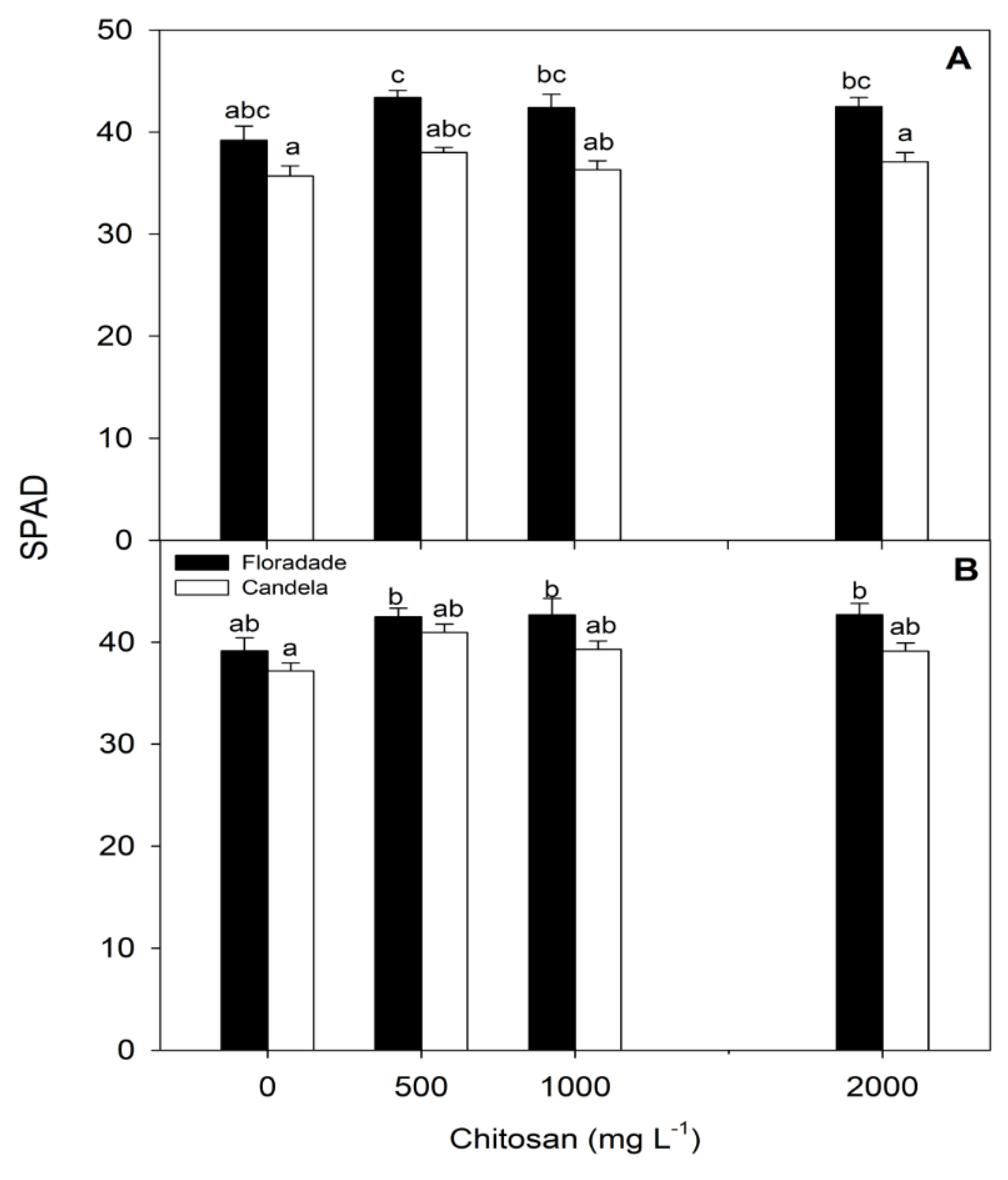

3.6. Chlorophyll Content

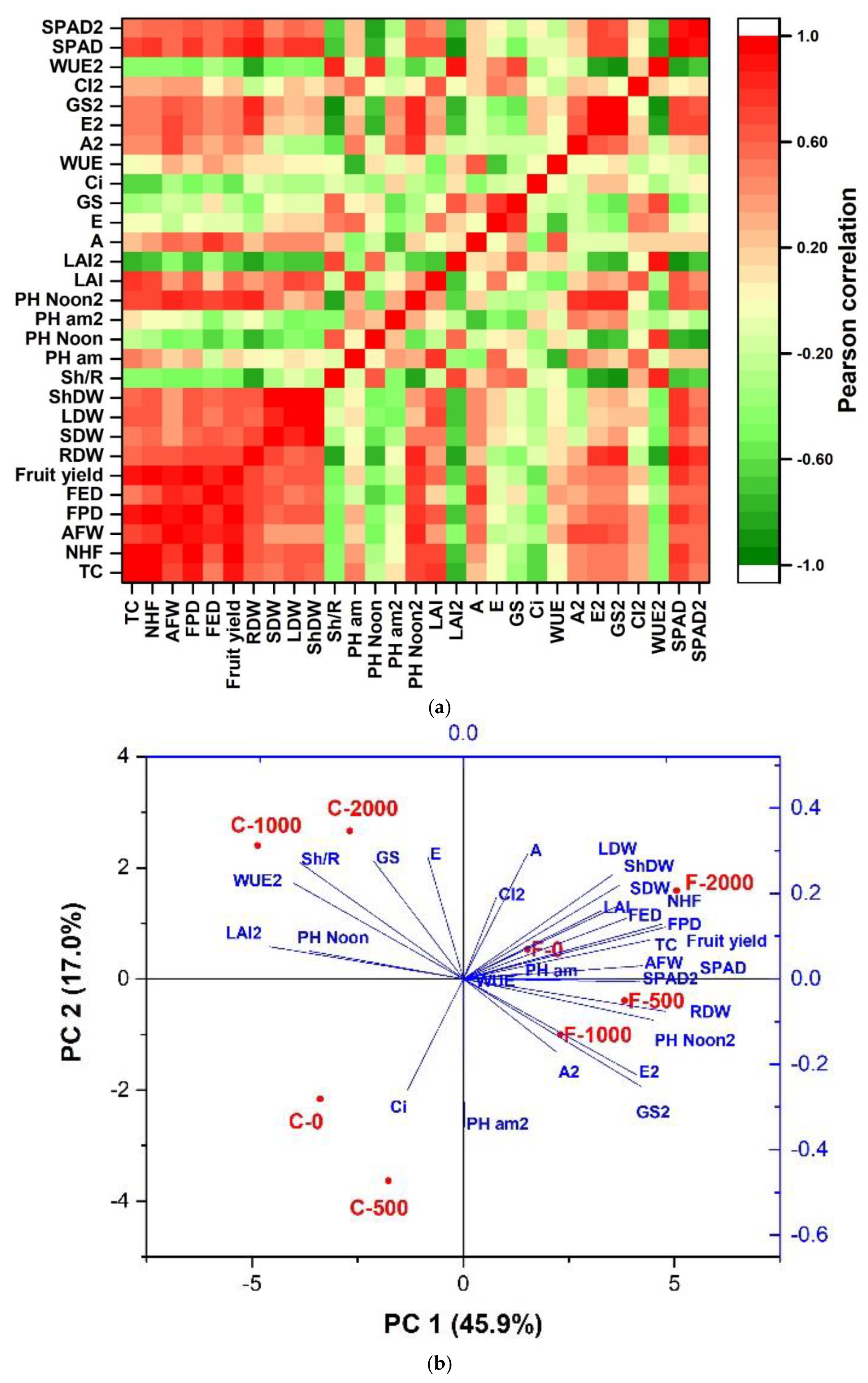

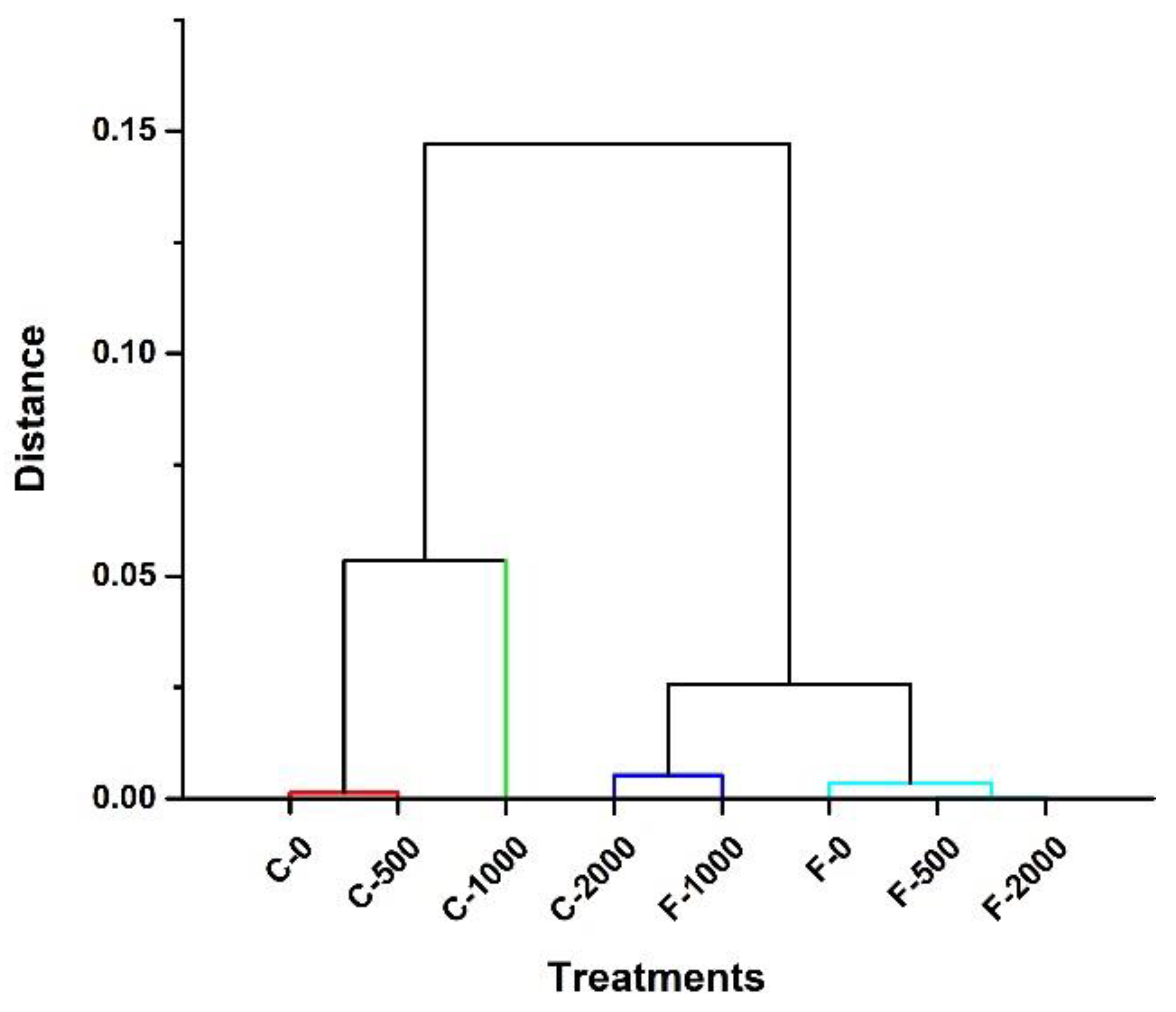

3.7. Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Campos, M.D.; Felix, M.D.R.; Patanita, M.; Materatski, P.; Albuquerque, A.; Ribeiro, J.A.; Varanda, C. Defense strategies: The role of transcription factors in tomato–pathogen interaction. Biology, 2022, 11(2), 235. [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, H.; Shao, Z.; Jian, Y.; Mao, Y.; Liu L.; Wang, Q. Carotenoid biofortification in tomato products along whole agro-food chain from field to fork. rends Food Sci Technol. 2022, 124, 296-308. [CrossRef]

- Terry Alfonso, E.; Falcón Rodríguez, A.; Ruiz Padrón, J.; Carrillo Sosa, Y.; Morales Morales, H. Respuesta agronómica del cultivo de tomate al bioproducto QuitoMax®. Cultivos Tropicales, 2017, 38(1), 147-154.

- Torres-Rodriguez, J.A.; Reyes-Pérez, J.J.; Quiñones-Aguilar, E.E.; Hernandez-Montiel, L.G. Actinomycete potential as biocontrol agent of phytopathogenic fungi: Mechanisms, source, and applications. Plants, 2022, 11(23), 3201.

- Sabiha-Javied., Siddque, N., Waheed, S., Uz Zaman, Q.; Aslam, A.; Tufail, M.; Nasir, R. Uptake of heavy metal in wheat from application of different phosphorus fertilizers. J. Food Compos. Anal., 2023, 115, 104958. [CrossRef]

- Guangbin, Z.; Kaifu, S.; Xi, M.; Qiong, H.; Jing, M.; Huang Q.; Ma, J.; Gong H.; Zhang Y.; Paustian, K.; Yan, X.; Hua, X. Nitrous oxide emissions, ammonia volatilization, and grain-heavy metal levels during the wheat season: Effect of partial organic substitution for chemical fertilizer. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ., 2021, 311, 107340. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Liu, B.; Xu, W.; Yu, L.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, J.; Tao, L.; Li Z; Zhang, Y. DNA damage and cell apoptosis induced by fungicide difenoconazole in mouse mononuclear macrophage RAW264. 7. Environ. Toxicol. 2022, 37(3), 650-659. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Mao, Y.; Li, S.; Li, T.; Wang, J.; Zhou, M.; Duan, Y. Molecular mechanism of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum resistance to succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor fungicides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70(23), 7039-7048.

- Reyes-Pérez, J.J.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, S.; Torres-Rodríguez, J.A.; Llerena-Ramos, L.T.; Hernández-Montiel, L.G.; Ruiz-Espinoza, F.H. Biofortificación con Silicio en el Crecimiento y Rendimiento de Pimiento (Capsicum annuum L.) en Ambiente Controlado. Terra Latinoamericana, 2023, 41, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Rodriguez, J.A.; Ramos-Remache, R.A.; Reyes-Pérez, J.J.; Quinatoa-Lozada, E.F.; Rivas-García, T. (2024). Silicio como Bioestimulante en el Cultivo de Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) y Agente de Control Biológico de Moniliophthora roreri. 2024, 42, 1-11 e1817. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Rodriguez, J.A.; Reyes-Perez, J. J.; Castellanos, T., Angulo, C.; Quinones-Aguilar, E. E.; Hernandez-Montiel, L.G; A biopolymer with antimicrobial properties and plant resistance inducer against phytopathogens: Chitosan. Not Bot Horti Agrobo., 2021, 49(1), 12231-12231.

- Qiu, S.; Zhou, S.; Tan, Y.; Feng, J.; Bai, Y.; He, J.; Cao, H.; Che, Q.; Guo, J.; Su, Z. Biodegradation and Prospect of Polysaccharide from Crustaceans. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 310. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, K., Ganesan, A.R., Ezhilarasi, P.N., Kondamareddy, K. K., Rajan, D. K., Sathishkumar, P., Rajarajeswaran, J., Conterno, L. Green and eco-friendly approaches for the extraction of chitin and chitosan: A review. Carbohydr. Polym., 2022, 287, 119349. [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Tafi, E.; von Seggern, N.; Falabella, P.; Salvia, R.; Thomä, J.; Febel E.; Fijalkowska M.; Schmitt E.; · Stegbauer, L.; Zibek, S. Purification of Chitin from Pupal Exuviae of the Black Soldier Fly. Waste Biomass Valor 2022, 13, 1993–2008. [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Fernandez, M., Marhuenda-Egea, F.C.; Lopez-Moya, F.; Arnao, M.B.; Cabrera Escribano, F.; Nueda, M.J.; Gunsé, B.; Lopez-Llorca L.V. Chitosan Induces Plant Hormones and Defenses in Tomato Root Exudates. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11:572087. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Ruiz-May, E.; Rajput, V.D.; Minkina, T.; Gómez-Peraza, R.L.; Verma, K.K.; Shekhawat, M.S.; Pinto, C.; Falco, V.; Quiroz-Figueroa, F.R. Viewpoint of Chitosan Application in Grapevine for Abiotic Stress/Disease Management towards More Resilient Viticulture Practices. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1369. [CrossRef]

- Suwanchaikasem, P.; Nie, S.; Idnurm, A.; Selby-Pham, J.; Walker, R.; &Boughton, B. A. Effects of chitin and chitosan on root growth, biochemical defense response and exudate proteome of Cannabis sativa. PEI, 2023, 4(3), 115-133. [CrossRef]

- El Amerany, F.; Meddich, A.; Wahbi, S.; Porzel, A.; Taourirte, M.; Rhazi, M.; Hause, B. Foliar Application of Chitosan Increases Tomato Growth and Influences Mycorrhization and Expression of Endochitinase-Encoding Genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 535. [CrossRef]

- Parvin, M.A.; Zakir, H.M.; Sultana, N.; Kafi, A.; Seal H.P. Effects of different application methods of chitosan on growth, yield and quality of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). Arch. Agric. Environ., 2019, 4(3): 261-267. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Pérez, J.J.; Enríquez-Acosta, E.A.; Ramírez-Arrebato, M.Á.; Zúñiga Valenzuela, E.; Lara-Capistrán, L.; Hernández-Montiel, L.G. Efecto del quitosano sobre variables del crecimiento, rendimiento y contenido nutricional del tomate. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc., 2020, 11(3), 457-465.

- Hussain, I.; Ahmad, S.; Ullah, I.; Ahmad, I.; Alam, M.; Khan, S.; Ayaz S. Foliar application of Chitosan modulates the morphological and biochemical characteristics of tomato. Asian J Agric & Biol. 2019, 7(3):365-372.

- Kumar, S.; Ye, F.; Dobretsov, S.; Dutta, J. Chitosan Nanocomposite Coatings for Food, Paints, and Water Treatment Applications. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9(12), Article 2409. [CrossRef]

- Costales-Menéndez, D.; Nápoles-García, M.C.; Travieso-Hernández, L.; Cartaya-Rubio, O.; Falcón-Rodríguez, A.B. Compatibilidad Quitosano-Bradyrhizobium aplicados a semillas y su efecto en el desarrollo vegetativo de soya (Glycine max (L.) Merrill). Agron. Mesoam. 2021, 32(3):869-887. [CrossRef]

- Attaran Dowom, S.; Karimian, Z.; Mostafaei Dehnavi, M. et al. Chitosan nanoparticles improve physiological and biochemical responses of Salvia abrotanoides (Kar.) under drought stress. BMC Plant Biol 2022, 22, 364 . [CrossRef]

- El Amerany, F.; Rhazi, M.; Balcke, G.;Wahbi, S.; Meddich, A.; Taourirte, M.; Hause, B. The Effect of Chitosan on Plant Physiology, Wound Response, and Fruit Quality of Tomato. Polymers 2022, 14, 5006. [CrossRef]

- dos Reis, C.O.; Magalhães, P. C. ; Avila, R.G.; Almeida, L.G.; Rabelo, V.M.; Carvalho, D. .; Cabral, D.F.; Karam, D.de Souza, T. Action of N-Succinyl and N,O-Dicarboxymethyl Chitosan Derivatives on Chlorophyll Photosynthesis and Fluorescence in Drought-Sensitive Maize. J Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 38, 619–630 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Salimi, A.Z.; Ardebili, O; Salehibakhsh. ‘Potential benefits of foliar application of chitosan and Zinc in tomato’. ran. J. Plant Physiol. 2019, (2), 2703-2708.

- Chakraborty, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Rahman, M.; Khan, M.A.R.; Bhowmik, P.; Mahmud, N.U.; Tanveer, M.; Islam, T. Mechanism of Plant Growth Promotion and Disease Suppression by Chitosan Biopolymer. Agriculture 2020, 10, 624. [CrossRef]

- Mukarram, M.; Khan, M.M.A., Kurjak, D; Corpas, F.J. Chitosanoligomers (COS) trigger a coordinated biochemical response of lemongrass (Cymbopogon flexuosus) plants to palliate salinity-induced oxidative stress. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8636. [CrossRef]

- Ávila, R.G.; Magalhães, P.C.; Ávila, R.G. ;· Magalhães, P.C.; Vitorino, L.C.; Bessa, L.A.; Dázio de Souza, K.R..;· Barros Queiroz, R.; Jakelaitis, A.; Teixeira, M.B. Chitosan Induces Sorghum Tolerance to Water Deficits by Positively Regulating Photosynthesis and the Production of Primary Metabolites, Osmoregulators, and Antioxidants. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 1156–1172 . [CrossRef]

- Lakshari, W.A.I.; Sukanya, M.; Hewavitharan, K.H.I.K. Effect of different concentrations of foliar application of chitosan on growth development of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) cultivar grown in Sri Lanka. J. Res. Technol. Eng., 2023, 4 (3), 01-08.

- Attia, M.S.; Osman, M.S.; Mohamed, A.S.; Mahgoub, H.A.; Garada, M.O.; Abdelmouty, E.S.; Abdel Latef, A.A.H. Impact of Foliar Application of Chitosan Dissolved in Different Organic Acids on Isozymes, Protein Patterns and Physio-Biochemical Characteristics of tomato Grown under Salinity Stress. Plants 2021, 10, 388. [CrossRef]

- Behboudi F, Tahmasebi-Sarvestani Z, Kassaee MZ, Modarres-Sanavy SAM, Sorooshzadeh A, Mokhtassi-Bidgoli A. Evaluation of chitosan nanoparticles effects with two application methods on wheat under drought stress. J Plant Nutr. 2019;42(13):1439–51.

- Ali, E.F.; El-Shehawi, A.M.; Ibrahim, O.H.M.; Abdul-Hafeez, E.Y.; Moussa, M.M.; Hassan, F.A.S. A vital role of chitosan nanoparticles in improvisation the drought stress tolerance in Catharanthus roseus (L.) through biochemical and gene expression modulation. PPB, 2021, 161, 166-175.

- Rabelo, V.M.; Magalhaes, P.C.; Bressanin, L.A.; Carvalho, D.T.; Reis, C.O.D.; Karam D.; Doriguetto, A.C.; Santos, M.H.D.; Santos Filho, PRDS; Souza, T.C. The foliar application of a mixture of semisynthetic chitosan derivatives induces tolerance to water deficit in maize, improving the antioxidant system and increasing photosynthesis and grain yield. Sci Rep. 2019; 9(1):1–13.

- Reyes-Pérez, J.J.; Rivero-Herrada, M.; García-Bustamante, E.L.; Beltran-Morales, F.A.; Ruiz-Espinoza, F.H. Aplicación de quitosano incrementa la emergencia, crecimiento y rendimiento del cultivo de tomate (Solanum lycopersicum L.) en condiciones de invernadero. Biotecnia, 2020,22(3), 156-163.

- Kahromi, S.; Khara, J. Chitosan stimulates secondary metabolite production and nutrient uptake in medicinal plant Dracocephalum kotschyi. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2021, 101(9), 3898-3907.

- Reyes-Pérez, J.J.; Rivero-Herrada, M.; Andagoya Fajardo, C. J.; Beltrán-Morales, F.A.; Hernández-Montiel, L.G.; García Liscano, A.E.; Ruiz-Espinoza, F. H. Emergencia y características agronómicas del Cucumis sativus a la aplicación de quitosano, Glomus cubense y ácidos húmicos. Biotecnia, 2021, 23(3), 38-44.

- Reyes-Pérez, J.J.; Llerena-Ramos, L.T.; Rivero-Herrada, M.; Pincay-Ganchozo, R.A.; Hernández-Montiel, L.G.; Ruiz-Espinoza, F.H. (2022). Agrobiological ef fectiveness of chitosane, humic acids and mycorrhzic fungi in two varieties of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Terra Latinoamericana, 2022, 40.

- Terry Alfonso, E.; Ruiz Padrón, J.; Rivera Espinosa, R.; Falcón Rodríguez, A.; Carrillo Sosa, Y. Bioproducts as partial substitutes for the mineral nutrition of the pepper crop (Capsicum annuum L.). Acta Agronómica, 2021, 70(3), 266-273.

- Amirkhani, M.; Netravali, A. N.; Huang, W.; Taylor, A.G. (2016). Investigation of soy protein–based biostimulant seed coating for broccoli seedling and plant growth enhancement. HortScience, 2016, 51(9), 1121-1126.

- Sharif, R.; Mujtaba, M.; Ur Rahman, M.; Shalmani, A.; Ahmad, H.; Anwar, T.; Tianchan, D.; Wang, X. The Multifunctional Role of Chitosan in Horticultural Crops; A Review. Molecules 2018, 23, 872. [CrossRef]

- Sathiyabama, M.; Bernstein, N.; Anusuya S, Chitosan elicitation for increased curcumin production and stimulation of defence response in turmeric (Curcuma longa L.), Ind. Crops Prod., 2016, 89, 87-94, . [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi Pirbalouti, A.; Malekpoor, F.; Salimi, A.; Golparvar, A. Exogenous application of chitosan on biochemical and physiological characteristics, phenolic content and antioxidant activity of two species of basil (Ocimum ciliatum and Ocimum basilicum) under reduced irrigation, Sci. Hortic., 2017, 217, 114-122, . [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, M.; Noreen, Z.; Aslam, M.; Shah, A.N.; Usman, S.; Waqas, A.; Alsherif, EA.; Korany, S.M.; Nazim, M. 2024. Chitosan modulated antioxidant activity, inorganic ions homeostasis and endogenous melatonin to improve yield of Pisum sativum L. accessions under salt stress Sci. Hortic., 2024,323,112509, . [CrossRef]

- Anjum, S.; Ain, Qu.; Sarwar, M.; Alam, M.W.; Mushtaq, Z.; Mukhtar, A.M.; Ashraf, I.; Alasmari, A. Chitosan Induced Modification in Morpho-Physiological, Biochemical and Yield Attributes of Pea (Pisum Sativum L.) Under Salt Stress. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr 2025, 25, 1311–1321 (). [CrossRef]

- Holguin-Peña, R. J.; Vargas-López, J. M.; López-Ahumada, G.A.; Rodríguez-Félix, F.; Borbón-Morales, C.G.; Rueda-Puente, E. O. Effect of chitosan and Bacillus amilolyquefasciens on sorghum yield in the indigenous area “Mayos” in Sonora. Terra Latinoamericana, 2020, 38(3), 705-714.

- Pincay-Manzaba, D.F.; Cedeño-Loor, J.C.; Espinosa Cunuhay, K.A. Efecto del quitosano sobre el crecimiento y la productividad de Solanum lycopersicum. Centro Agrícola, 2021, 48(3), 25-31.

- González, L.G.; Paz, I.; Martínez, B.; Jiménez, M.C.; Torres, J. A.; Falcón, A. Respuesta agronómica del cultivo del tomate (Solanum lycopersicum, L) var. HA 3019 a la aplicación de quitosana. UTCiencia, 2017, 2(2), 55-60.

- González Peña, D.; Costales, D.; Falcón, A.B. (2014). Influencia de un polímero de quitosana en el crecimiento y la actividad de enzimas defensivas en tomate (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Cultivos Tropicales, 2014, 35(1), 35-42.

- Chanaluisa-Saltos, J.S.; Sánchez, A.R.Á.; Reyes-Pérez, J.J.; Lizarde, N.A. Respuesta agronómica y fitosanitaria de plantas de tomate (Solanum lycopersicum L.) a la aplicación de quitosano en condiciones controladas. Revista Científica Agroecosistemas, 2022, 10(1), 139-145.

- Torres Rodríguez, J.A.; Reyes Pérez, J.J.; González Rodríguez, J.C. Efecto de un bioestimulante natural sobre algunos parámetros de calidad en plántulas de tomate (Solanum lycopersicum, L.) bajo condiciones de salinidad. Biotecnia, 2016, 18(2), 11-15.

- Reyes-Pérez, J.J.; Rivero-Herrada, M.; Solórzano-Cedeño, A.E.; Carballo-Méndez, F.D.J.; Lucero-Vega, G.; Ruiz-Espinoza, F.H. Aplicación de ácidos húmicos, quitosano y hongos micorrízicos como influyen en el crecimiento y desarrollo de pimiento. Terra Latinoamericana, 2021, 39. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Pérez, J.J.; Enríquez-Acosta, E.A.; Ramírez-Arrebato, M.Á.; Rodríguez-Pedroso, A.T.; Rivero-Herrada, M. Respuesta de plántulas de cultivares de tomate a la aplicación de quitosano. Centro Agrícola, 2019, 46(4), 21-29.

- Peralta-Antonio, N.; Bernardo de Freitas, G.; Watthier, M.; Silva Santos, R H.Compost, bokashi y microorganismos eficientes: sus beneficios en cultivos sucesivos de brócolis. Idesia (Arica), 2019, 37(2), 59-66.

- Morales Guevara, D.; Dell Amico Rodríguez, J.; Jerez Mompié, E.; Hernández, Y.D.; Martín Martín, R. Efecto del QuitoMax® en el crecimiento y rendimiento del frijol (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Cultivos Tropicales, 2016, 37(1), 142-147.

- Cardona-Ayala, C.; Jarma-Orozco, A.; Araméndiz-Tatis, H.; Peña-Agresott, M.; Vergara-Córdoba, C. Respuestas fisiológicas y bioquímicas del fríjol caupí (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.) bajo déficit hídrico. Rev. Colomb. Cienc., 2014, 8(2), 250-261.

- Pedroza-Sandoval, A.; Trejo-Calzada, R.; Sánchez-Cohen, I.; Samaniego-Gaxiola, J.A.; Yáñez-Chávez, L.G. Evaluation of three pinto bean varieties under drought and irrigation in Durango, Mexico. Agron. Mesoam., 2016, 27(1), 167-176.

- Bittelli, M.; Flury, M.; Campbell, G. S.; Nichols, E.J. Reduction of transpiration through foliar application of chitosan. Agric. For. Meteorol., 2001, 107(3), 167-175.

- Iriti, M.; Picchi, V.; Rossoni, M.; Gomarasca, S., Ludwig, N.; Gargano, M.; Faoro, F. Chitosan antitranspirant activity is due to abscisic acid-dependent stomatal closure. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 2009, 66(3), 493-500.

- Morales-Guevara, D.; Dell Amico-Rodríguez, J.; Jerez-Mompie, E.; Rodríguez-Hernández, P.; Álvarez-Bello, I.; Díaz-Hernández, Y.; Martín-Martín, R. Efecto del Quitomax® en plantas de (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) sometidas a dos regímenes de riego. II. Variables Fisiológicas. Cultivos Tropicales, 2017, 38(4), 92-101.

| Variable | Variety | Control | 500 mg L-1 | 1000 mg L-1 | 2000 mg L-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height (cm) | Floradade | 106.5 ± 3.0 b | 114.27 ± 2.1 ab | 117.20 ± 2.1 ab | 116.53 ± 1.8 ab |

| Candela F1 | 120.02 ± 2.5 c | 123.47 ± 2.1 bc | 125.9 ± 1.8 b | 130.47 ± 1.9 a | |

| Stem diameter (mm) | Floradade | 9.40 ± 0.3 b | 9.67 ± 0.2 b | 9.67 ± 0.2 b | 10.13 ± 0.4 a |

| Candela F1 | 8.20 ± 0.3 b | 10.30 ± 0.2 a | 10.30 ± 0.3 a | 10.80 ± 0.21 a | |

| Root Dry Weight (RDW) (g) | Floradade | 52.8 ± 7.1 c | 56.7 ± 5.4 b | 58.3 ± 6.5 b | 70.3 ± 6.5 a |

| Candela F1 | 28.3 ± 2.0 c | 36.7 ± 4.7 b | 38.7 ± 4.7 b | 48.2 ± 1.9 a | |

| Leaf Dry Weight (LDW) (g) | Floradade | 38.0 ± 2.5 c | 42.0 ± 3.7 b | 42.7 ± 2.1 b | 44.0 ± 1.9 a |

| Candela F1 | 32.2 ± 3.7 c | 36.7 ± 1.7 b | 37.2 ± 2.8 b | 39.3 ± 2.4 a | |

| Stem Dry Weight (SDW) (g) | Floradade | 23.8 ± 1.6 b | 26 .0 ± 1.3 a | 27.2 ± 1.9 a | 27.0 ± 0.7 a |

| Candela F1 | 15.5 ± 1.1 d | 18.7 ± 1.9 c | 21.2 ± 2.2 b | 23.8 ± 1.6 a | |

| Shoot Dry Weigh (ShDW) (g) | Floradade | 64.8 ± 4.6 c | 65.8 ± 3.3 c | 69.8 ± 3.7 b | 71.0 ± 2.3 a |

| Candela F1 | 50.7 ± 4.5 c | 55.8 ± 4.1 b | 57.8 ± 3.5 b | 63.2 ± 3.2 a | |

| Shoot/Root (Sh/R) | Floradade | 1.0 ± 0.2 b | 1.2 ± 0.1 a | 1.3 ± 0.1 a | 1.4 ± 0.1 a |

| Candela F1 | 1.1 ± 0.2 b | 1.6 ± 0.3 b | 2.1 ± 0.4 a | 2.1 ± 0.2 a |

| Variable | Variety | Control | 500 mg L-1 | 1000 mg L-1 | 2000 mg L-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit Yield (FY)(t ha-1) | Floradade | 5.41 ± 0.07 c | 6.60 ± 0.09 b | 7.19 ± 0.13 a | 8.21 ± 0.22 a |

| Candela F1 | 5.03 ± 0.10 d | 6.37 ± 0.16 c | 6.93 ± 0.07 b | 7.67 ± 0.08 a | |

| Total clusters (TC) | Floradade | 2.07 ± 0.2 d | 2.5 ± 0.2 c | 2.87 ± 0.2 b | 3.07 ± 0.2 a |

| Candela F1 | 1.47 ± 0.1 a | 1.47 ± 0.1 a | 1.27 ± 0.1a | 2.0 ± 0.2 ab | |

| Number of Harvested Fruits (NHF) | Floradade | 4.87 ± 0.3 b | 5.53 ± 0.5 b | 3.93 ± 0.4 ab | 5.73 ± 0.6 b |

| Candela F1 | 2.87 ± 0.3 b | 2.8 ± 0.3 b | 2.93 ± 0.3 b | 4.13 ± 0.4 a | |

| Polar Diameter of the Fruit (FPD) | Floradade | 15.1 ± 1.3 bc | 17.3 ± 1.3 b | 20.8 ±1.8 a | 21.2 ± 2.5 a |

| Candela F1 | 9.5 ± 1.0 c | 11.5 ± 1.4 b | 11.6 ±1.3 b | 15.4 ± 1.3 a | |

| Equatorial Diameter of the Fruit (FED) | Floradade | 16.7 ± 1.5 c | 20.1 ± 1.4 b | 22.7 ± 1.9 b | 23.6 ± 2.6 a |

| Candela F1 | 11.2 ± 1.1 c | 13.1 ± 1.5 b | 13.4 ± 1.5 b | 17.5 ± 1.4 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).