Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Epistemological and Pedagogical Foundations of Environmental Education: Integrating Sustainability, Planetary Health, and Science Education

- Selecting and prioritizing variables according to relevance criteria.

- Controlling and predicting experimental outcomes.

- Organizing and clarifying data sequences.

- Objectivity is not the absence of values but the product of social negotiations and communal consensus

- Scientific observation is mediated by prior experiences, expectations, and theoretical frameworks.

- Theories and laws hold validity within specific historical contexts and are revised rather than discarded in light of anomalies.

2.2. Implications for Education

2.3. Planetary Health Education: An Emerging Paradigm or an Emerging Field?

3. Methodology

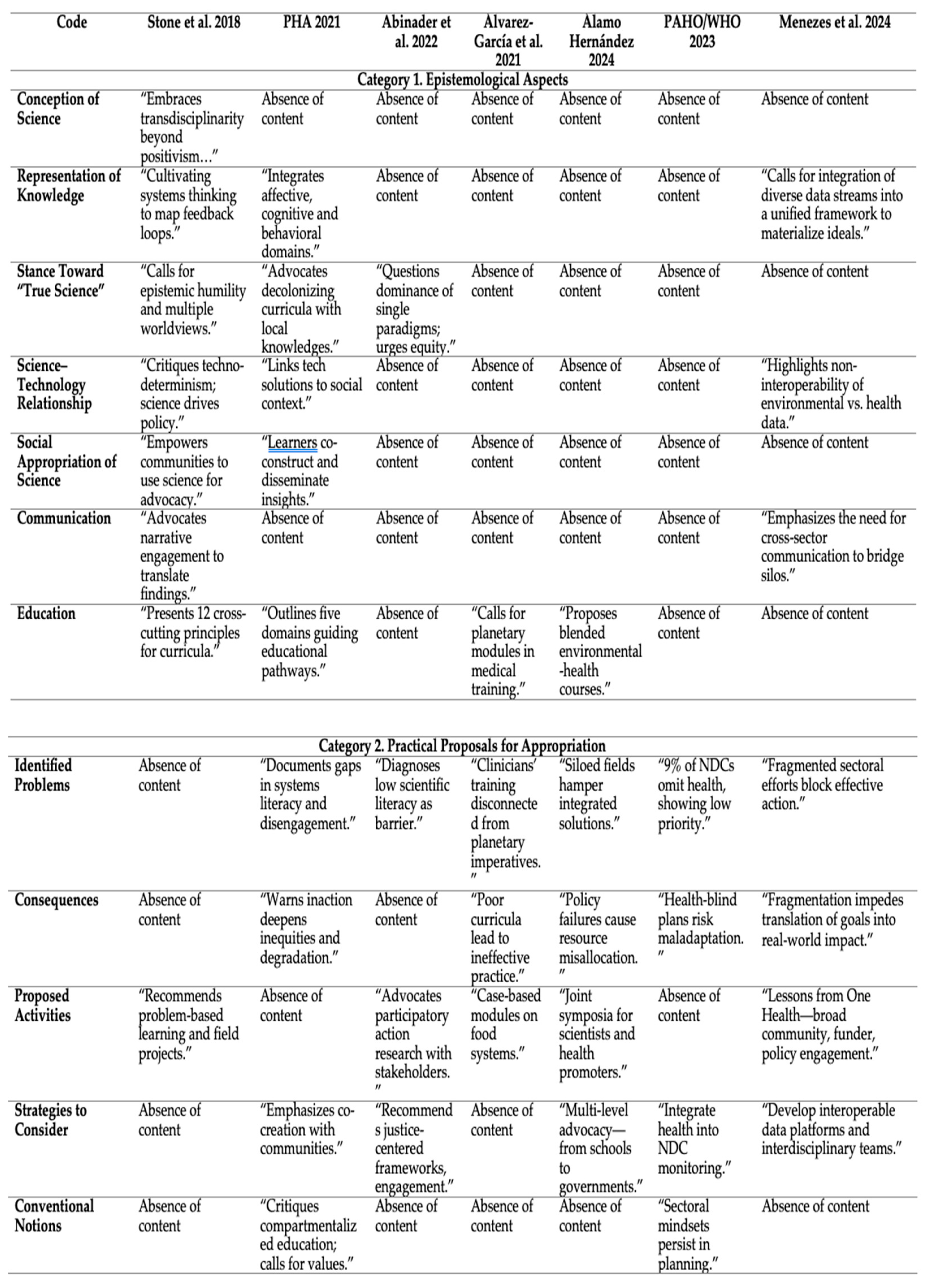

3. Results

3.2. Principles for Environmental and Sustainability Education from a Planetary Health Perspective

3.2.1. Recognition of the Self, the Other, and Oikos from an Environmental Ethics and Value System, Through the Use of Poetics and Aesthetics:

3.2.2. Recognition of Territory and the Theory of Place for Sustainability

3.2.3. Enhancement of Different Types of Knowledge for Socio-Environmental Justice

3.2.4. Education and Communication for Transformation

3.2.5. Governance and Policy for Planetary Health

3.2.6. Community Mobilization and Advocacy for Planetary Health

3.2.7. Systems Thinking and Transdisciplinary Collaboration

3.2.8. Future-Oriented Decision-Making and Adaptive Strategies

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morin, E.; Kern, B. Terre-Patrie; Publisher: Seuil, 1993; pp. 224.

- Harman, J.; Lorandos, D.; Sherry, A.; Kaufman, M. Danger of Misinformation and Science Denial: Background, Modern Examples, Future Action. Journal of Social Issues. 2025, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khun, T.S. (1970). The structure of scientific revolutions (2nd ed., enlarged). University of Chicago Press.

- Mejia-Caceres, M.A.; Zambrano, A. (2018). Ciencia, Cultura y Educación Ambiental: Una propuesta para los educadores. Programa Editorial Universidad del Valle. Cali: Colombia.

- Spindler, G. (1987). Education and cultural process: Anthropological approaches (2nd ed.). Waveland Press.

- Wolcott, H.F. (1991). Propriospect and the acquisition of culture. In M. C. Albright & A. K. Bock (Eds.), The acquisition of culture (pp. 187–212). University Press of America.

- Geertz C, (1973). The Interpretation of culure. New York: Basic Books.

- Sauvè, L. (2005). Uma Cartografia das Correntes em Educação Ambiental. In: SATO, M.; Carvalho, I. (Eds.). Educação ambiental. Porto Alegre: Artmed.

- Robert B. Stevenson , Arjen E. J. Wals , Joe E. Heimlich , and Ellen Field.

- Costa, C.A.; Loureiro, C.F. Educação Ambiental crítica e conflitos ambientais: reflexões à luz da América Latina. E-curriculum. 2024, 22, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florencio da Silva, R.; Torres-Rivera, A.D.; Alves Pereira, V.; Regis Cardoso, L.; Becerra, M.J. Critical Environmental Education in Latin America from a Socio-Environmental Perspective: Identity, Territory, and Social Innovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unesco, (2025). Education for sustainable development. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved from https://uis.unesco.org/en/glossary-term/education-sustainable-development.

- Sterling, S. (2001). Sustainable education: Re-visioning learning and change. Green Books.

- Mora, W. Educación ambiental y educación para el desarrollo sostenible ante la crisis planetaria: demandas a los procesos formativos del profesorado. Tecne, Episteme y Didaxis. 2009, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, M.; Vasconcellos, M. Relações entre Educação Ambiental e Educação em Ciências na Complementaridade dos Espaços Formais e Não Formais de Educação. Educar 2006, 27, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, B.; Bomfim, A. (2011). A “Teoria do fazer” em Educação Ambiental Crítica: Uma Reflexão Costruída em Contraposição à Educação Ambiental Conservadora. Atas do VIII ENPEC: Encontro Nacional de Pesquisa em Educação em Ciências.

- Carvalho, I. (2004). Educação Ambiental Crítica: Nomes e Endereçamentos da Educação. In: Identidades da Educação Ambiental Brasileira. Brasilia: Ministério do Meio Ambiente.

- Tozoni Reis, M. (2004). Educação Ambiental: Natureza, Razão e História. Campinas, SP: Autores Associados.

- Freire paulo- dialogue.

- Giroux, H. (1985).Teorías de la Reproducción y la Resistencia en la Nueva Sociología de la Educación: un Análisis Crítico. Cuadernos Políticos, n. 44, p. 36–65.

- Comte, A (1842) Curso de Filosofia positiva. Paris: Bachelier libraire pour les mathematiques.

- Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- Nasir, N.S.; Rosebery, A.S.; Warren, B.; Lee, C.D. (2006). Learning as a cultural process: Achieving equity through diversity. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences.

- Calabrese Barton, A.; Tan, E. We Be Burnin’! Agency, Identity, and Science Learning. Journal of the Learning Sciences 2010, 19, 187–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, M.; Marin, A. Nature–Culture Constructs in Science Learning: Human/ Non-Human Agency and Intentionality. Journal of Research in Science Teaching. 2015, 52, 430–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikenhead, G.S.; Michell, H. (2011). Bridging cultures: Indigenous and scientific ways of knowing nature. Pearson.

- Gruenewald, D.A. The best of both worlds: A critical pedagogy of place. Educational Researcher 2003, 32, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2021). Reimagining our futures together: A new social contract for education. UNESCO Publishing.

- Whitmee, S.; et al. Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: Report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. The Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, R.; Lo, S. Planetary health: A new science for exceptional action. The Lancet 2015, 386, 1921–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.S.; Frumkin, H. (2020). Planetary Health: Protecting Nature to Protect Ourselves. Island Press.

- Rockström, J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanello, M.; et al. The 2021 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: code red for a healthy future. The Lancet 2021, 398, 1619–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.S. Planetary health: Protecting human health on a rapidly changing planet. The BMJ 2017, 358, j3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, M.W.; Buse, C.G.; Allison, S. Towards an educational praxis for planetary health: A call for transformative, inclusive, and integrative approaches for learning and relearning in the Anthropocene. The Lancet Planetary Health 2023, 7, e77–e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, C.; Potter, T. (2021) – Framework for Planetary Health Education. Planetary Health Alliance.

- Stone, S.B.; Myers, S.S.; Golden, C.D. Cross-cutting principles for planetary health education. The Lancet Planetary Health 2018, 2, e192–e193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abinader, R.; Rasheed, M.; Khan, M.; Ruff, T. Navigating fundamental tensions towards a decolonial relational vision of planetary health. The Lancet Planetary Health 2022, 6, e860–e862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-García, C.; López-Medina, I.M.; Sanz-Martos, S.; Álvarez-Nieto, C. Salud planetaria: Educación para una atención sanitaria sostenible. Educación Médica 2021, 22, 352–357, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edumed.2021.08.001Álamo Hernández, U. (2024). Salud y cambio climático: Análisis de los planes nacionales de acción climática en América Latina. ResearchGate. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO)/World Health Organization (WHO). (2023). Planetary health: Integrating climate and health into national policies in the Americas. https://www.paho.org/en/documents/planetary-health-2023.

- Prescott, S.L.; et al. The Microbiome and the Origins of Health and Disease. Lancet Planetary Health 2018, 2, e356–e365. [Google Scholar]

- Rockström, J.; et al. Planetary Boundaries. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; et al. Our Future in the Anthropocene Biosphere. Ambio 2021, 50, 834–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO (2017). Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives.

- Lin, W.; Chang, Y.C.; Chen, P.F. Environmental aesthetics and professional development for university teachers in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A. (2013). Enlivenment: Towards a poetics for the Anthropocene. Heinrich Böll Foundation. https://www.boell.de/en/content/enlivenment-towards-poetics-anthropocene.

- Abram, D. (1996). The spell of the sensuous: Perception and language in a more-than-human world. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Kagan, S. (2011). Art and sustainability: Connecting patterns for a culture of complexity. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

- Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Chelsea Green.

- Cullinan, C. (2011). Wild law: A manifesto for earth justice. Green Books.

- Kauffman, C.; Martin, P. Constructing rights of nature norms in the US, Ecuador, and New Zealand. Global Environmental Politics 2017, 18, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, D.; Fullilove, R. Mobilizing community health workers to achieve environmental justice and healthcare sustainability. J Public Health Policy. Epub 2024 Jul 5. 2024, 45, 588–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capra, F.; Luisi, P.L. (2014). The Systems View of Life. Cambridge University Press.

- Sterling, S. Transformative Learning and Sustainability. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development 2010, 4, 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, R. Learning, the Future, and Complexity. European Journal of Education 2015, 50, 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; et al. Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability. Ecology and Society 2004, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC (2022). Sixth Assessment Report: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability.

- Gardiner, S.M. (2011). A Perfect Moral Storm: The Ethical Tragedy of Climate Change. Oxford University Press.

|

| 1 Epistemological Dimensions and Practical Strategies for the Social Appropriation of Science in Planetary Health. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).