1. Introduction

The global community today faces an unprecedented convergence of environmental, economic, and social crises, underscoring the urgent need for transformative action. In response, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development sets forth an ambitious vision to reshape our world; however, despite this framework, progress toward achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) has been slow [

1]. Progress towards health-related SDG targets and universal health coverage (UHC) remains insufficient to meet the 2025 goals. On a global scale, in 2000, a person aged 30 years had a 22.7% chance of dying from one of the four leading chronic diseases (heart disease, cancer, lung disease, or diabetes) before reaching the age of 70 [

2]. Adding to this challenge is the growing burden of malnutrition, with over one billion people living with obesity, alongside hundreds of millions of children under five who suffer from stunting, wasting, or being overweight [

2]. As of 2024, 1.1 billion of the 6.3 billion people worldwide live in acute multidimensional poverty, with over half of them being children [

3]. Between 713 and 757 million people faced hunger in 2023, or one out of every eleven people globally, far from achieving SDG 2, Zero Hunger [

4]. Moreover, acute hunger has continued to rise in 2024 for the sixth consecutive year, with around 295 million people now experiencing high levels of acute food insecurity [

5].

Central to these interconnected crises is environmental degradation and biodiversity loss, primarily driven by human activities. Human actions threaten around 25% of assessed animal and plant species, placing about 1 million species at risk of extinction within decades, with current rates far exceeding the average of the past 10 million years [

6]. Simultaneously, the average size of wildlife populations has fallen by an alarming 73% between 1970 and 2020 [

7]. The world’s food system is the primary driver of biodiversity loss, with agriculture identified as a threat to 24,000 of the 28,000 species at risk of extinction [

8]. Despite this massive degradation, humanity continues to demand more from the Earth, utilizing the equivalent of 1.6 Earths to maintain the current way of life, outstripping the planet's ability to regenerate [

9].

This unsustainable pressure on natural resources is, in large part, driven by the rapid pace of economic growth [

10,

11,

12]. Over the last decade (2010–2019), global net anthropogenic Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions reached unprecedented levels, driven by rising GDP per capita and population growth, which have been the strongest contributors to CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion [

13]. Correspondingly, economic growth measured by GDP per capita (GDPPC) shows a positive correlation with ecological footprint, since expanding economies typically result in increased energy consumption, industrial production, and overall consumption [

12]. The significant surge in economic growth has transformed people's lifestyles and elevated their consumption of natural resources beyond basic necessities [

14]. Such patterns of consumerism, which have been criticized by Ref [

15], are closely linked to market-driven business practices that prioritizing short-term gains and neglecting environmental responsibility [

16,

17]. These behaviors are deeply embedded within prevailing worldviews and political-economic structures, suggesting that the roots of unsustainability go beyond technical or policy challenges.

Recent research has therefore defended the idea that the epistemological and paradigmatic bases of the unsustainability crisis need to be explored. As Ref [

18] notes, global environmental change is not only about material systems but also involves value systems and patterns of thought. Ref [

19,

20] likewise argued that environmental problems are rooted in human consciousness and cultural narratives, a sentiment echoed by thinkers such as Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, who believed that “a polluted environment is a symptom of a polluted mind” [

21]. Understanding these deep-seated paradigms is thus central to envisioning and enabling a transition toward a sustainable future.

The strategic importance of education to spearhead this shift has long been acknowledged. However, traditional models of education, especially in business schools have been criticized for aligning with dominant economic paradigms and failing to address the deeper ethical and ecological challenges of sustainability [

10,

22,

23]. Rather than producing attention, empathy, systemic thinking, such models often reinforce extractive logics and narrow professional rationalities. Although sustainability-centric education model has achieved much in including for the sustainability in the curricula, it has been criticized for being too economic-oriented and neglect of the changing of the worldviews and values [

24].

There is, therefore, an increasing demand for transformative dimensions of education that go beyond knowledge transmission toward developing critical consciousness, ecological empathy, and the capacity for systemic change. Education, as Ref [

25] discussed, is not only a process of transferring environmental knowledge, but also to shape moral perception and behavioral intention toward sustainability. This will require re-imagining education as not only a means to solve environmental problems but as a source of deep inquiry into meaning, identity and our relationship to the world.

This article seeks to contribute to this vital and transformative trajectory by discerning deep-seated paradigms of unsustainability which inform the conceptualizations and practices of sustainability. This study provides conceptual insights for educational practice, by emphasizing the importance of developing new leaders who are critical, ecological, and systemic thinkers. Through specifying the underlying paradigms that maintain unsustainability, and relating these to the transformative potential of education, this research contributes to a growing body of literature that seeks to move beyond surface-level reform and toward paradigm-level change.

2. Materials and Methods

This study follows a qualitative exploratory methodology, particularly suited for capturing the complex and abstract concepts underlying deeply embedded paradigms of unsustainability [

26]. The research integrates both primary data collected through semi-structured interviews and secondary data from relevant literature, journals, scientific articles, and other supporting documents that provide theoretical foundations. This involves creating or expanding existing theories by adding new propositions or clarifying the relationships between existing constructs [

27]. In addition, this process of inferring, based on the assumption that knowledge comes from known thing, need that the reasons of the inferences are clearly stated [

28], thereby contributing to the conceptual development of the understanding of the root causes of unsustainability.

2.1. Sampling and Participant Selection

This study employed purposive sampling to select eight experts with extensive experience and fathom understanding and concepts of unsustainability. Sampling was carefully planned to enable selected participants to accurately reflect on the research goals by contributing valuable, informed perspectives. According to Ref [

29], the competence of interviewed experts significantly influences the quality of data obtained; therefore, participants were selected for their relevant knowledge and experience. In this research, all experts have more than 10 years of professional experience in the field, ensuring deep expertise and understanding of the subject matter.

To ensure a well-rounded and multi-faceted exploration of unsustainability, participants were purposively recruited from various sectors of society (education, environmental sustainability and business). This multidisciplinary approach was designed to capture a broad range of perspectives and strategies. Ref [

30] supports this approach by asserting that expert knowledge is sui generis, as it integrates explicit and tacit elements, is socially embedded and institutionalized, and that the selection of interviewees must consider their social and functional contexts as well as their alignment with the research goals. Including experts from various roles, such as representatives from NGOs, international agencies, and policy-making institutions, further add the richness of addressing the complexity and multi-sided nature of the sustainability challenges.

Table 1 provides a detailed summary of practice of each expert, concerning academia and education, business operations, environmental and sustainability, and NGOs, international organizations, and policy. This diversity of expertise enhances the study by bringing into focus a range of critical perspectives around the question of unsustainability and the potential of education to challenge these paradigms.

2.2. Data Collection Procedures

Data collection in this study relied on both primary and secondary sources to build a comprehensive understanding of unsustainability and its impacts. The semi-structured interviews served as the primary avenue for collecting primary data, a common qualitative technique that allows for depth and flexibility while also ensuring that all informants are covered on central themes. In terms of epistemological objectives, these interviews are exploratory and are meant to open up new or less clear research territory [

30].

The interview guidelines in this study were derived from the research questions, but some extra questions were added in order to allow the interviewees to provide free comments on related subjects. The semi-structured nature facilitated in-depth exploration of the unsustainability concept with interviewers able to probe for and respond to emerging themes. This design reflects the nature of semi-structured interviews in expert contexts, which combine openness and structure by using a topic guide to steer discussions toward important themes [

31]. This approach aligns with the conception of ‘problem-centered, semi-structured interviews,’ where ‘problem-cantered’ refers to the focus and communication of interviews on socially relevant problems [

32].

The in-depth interview was developed around three primary research questions:

RQ1: Sustainability: How do participants conceptualize and identify sustainability? From this theme, the study aimed to uncover the systemic factors contributing to unsustainability from the perspectives of each expert in their respective fields.

RQ2: Business-Sustainability: How do experts conceptualize and assess business-sustainability? This theme explored the experts' views on how current business models and policies contribute to unsustainability and the potential for transformation.

RQ3: Education: What contribution does education provide to unsustainability and to moving towards sustainability? This theme gathered insights into the fundamental aspects of education that need to be reformed or targeted to challenge unsustainability and promote sustainability.

In addition to the primary data obtained in interviews, secondary data were collected systematically from a wide range of academic literature, policy documents, and reports. These secondary sources played a crucial role in supporting the primary data and situating the study’s findings within the broader context of existing research on sustainability, business practices, and education for sustainability. Secondary data, including relevant literature, journals, scientific articles, and other supporting documents, serve as essential theoretical foundations for advancing knowledge [

27,

28].

Consistent with this, Ref [

33] highlights that literature reviews are key to knowledge building and readying an expert interview study. By providing an overview of important issues and guiding interview schedules, literature reviews are helpful in the preparation of an adequate scope of interview topics and a reasonably good grasp of underlying theories, assumptions, and contextual considerations. Toward that end, this approach enables the creation of precise and topical questions. In addition, articles and policy documents from academia give access to theoretical and methodological perspective for interpreting interview data.

Sources of secondary data included were peer-reviewed scholarly articles and books on the topic of sustainability and environmental concerns; and policy reports on sustainable development, business, and environmental; and documents issued by international organizations and NGOs specifically addressing sustainability problems and conceptions about sustainability. These sources also helped identify gaps in the literature and guided the development of the study’s theoretical framework.

2.3. Data Analysis: Thematic Analysis

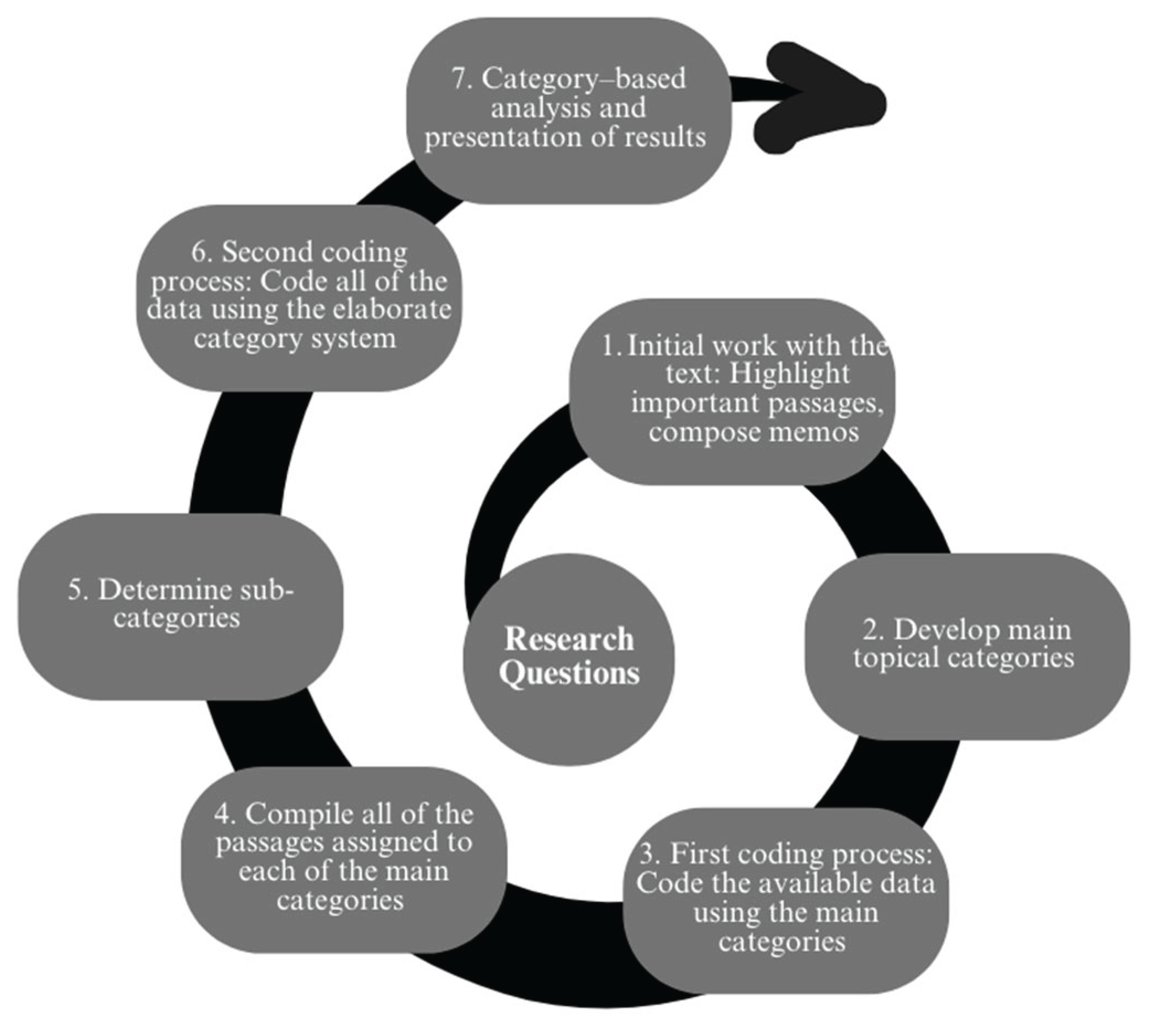

The data from semi-structured interview were analyzed with inductive thematic analysis, which is a method often used in qualitative research to interpret and present patterns and themes in the data [

34]. Initial codes were abstracted and organized into more complex categories and themes, allowing for deeper insight and coherence. Themes were categorized according to their relevance to unsustainability and the transformative role of education in shifting these paradigms. The analysis followed the seven-step procedure proposed by Kuckartz [

34], as illustrated in

Figure 1, and was grounded in the construction of interpretative categories using a structured coding system, as outlined by [

26,

35,

36].

The coding process was conducted in two cycles, following the approach introduced by Miles et.al [

26]:

First cycle (exploratory coding): Open coded to identify initial themes and concepts. Where possible, in vivo coding in participants’ own words was used in order to be as true to the participants’ experience in this stage of analysis as possible. This cycle aimed to identify common patterns from interviews such as system-level forces driving unsustainable performance in business, policy and education.

Second cycle (focused coding): Coding became more focused and structured. Initial codes were abstracted and organized into more complex categories and themes, allowing for deeper insight and coherence. Themes were categorized according to their relevance to unsustainability and the transformative role of education in shifting these paradigms.

To ensure methodological rigor, all data were fully coded following established quality criteria and organized into a comprehensive codebook. The coding process was supported by NVivo 12 software, which facilitated the systematic organization of nodes and parent nodes, tracking of emerging themes, and documentation of patterns [

37]. Each node represents an idea, theme, or category emerging from the data and serves as a repository for all relevant data references [

26,

37]. Categorization then organizes these nodes into broader categories based on similarities or patterns, enabling a coherent and structured understanding that supports deeper interpretation [

38]. Prior to coding analysis, all audio recordings from interviews were transcribed verbatim.

2.4. Triangulation and Data Validation

To enhance the trustworthiness and credibility of the findings, triangulation and validation methods common in qualitative research were applied [

39]. Triangulation strengthened results by integrating multiple sources, methods, and perspectives, enabling cross-validation and broadening the analysis [

26,

39,

40]. Building on this, trustworthiness was further ensured through a series of interconnected validation procedures [

41].

Firstly, data source triangulation compared and cross-validated interview data with information obtained from literature reviews and document analysis. This comparison verified the reliability of the data and enriched the depth of understanding the topic. Secondly, perspective triangulation involved deliberately exploring various viewpoints to capture the complexity of the phenomena, enabling the inclusion of complementary as well as contradictory insights. Parallel coding comparisons were performed to examine the levels of shared meaning or themes between participants. This approach enhanced the internal validity and strengthened the findings. Ultimately, triangulation methods utilized interviews with literature review to minimize methodological moderator and achieve wider data coverage [

40].

Validity, considered one of the strengths of qualitative research, involves assessing whether the findings accurately represent the perspectives of the researchers, the participants, and the intended audience [

42]. At first, communicative validation was achieved by the participants of interviews when experts were verifying the information in their statements to make it clear and coherent according to their intentions. This was a way for participants to give feedback, clarification, or confirmation about the researcher’s interpretations which helped to reduce the risk of subjective bias. This process also fostered shared understanding between the interviewer and participants, promoting standardized interpretation. Subsequently, member checking was carried out by sharing preliminary analyses with the research team and selected participants to obtain feedback. This process also acted to reduce the potential for researcher bias in interpretation of the data.

Following Ref [

35], all interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim with time stamps to ensure transcript accuracy and precise referencing. Audio recordings enhance transparency and validity by making the analysis auditable and increasing confidence in the findings. Every word, intonation, and nuance are captured, providing richer data and minimizing distortion from memory lapses or recording errors. Transcriptions were done manually and assisted by software such as listening.oi to ensure completeness and accuracy.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Coding and Thematic Categorization

Qualitative data analysis followed a strict two-stage coding method, in line with recognized qualitative approaches [

26,

34]. Beginning with a thorough reading of the interview transcripts, initial codes were developed deductively based on the study’s guiding research questions and theoretical foundations. This first cycle of open coding prioritized in vivo codes to preserve the authenticity of expert expressions, allowing for the emergence of broad thematic constructs relevant to unsustainability.

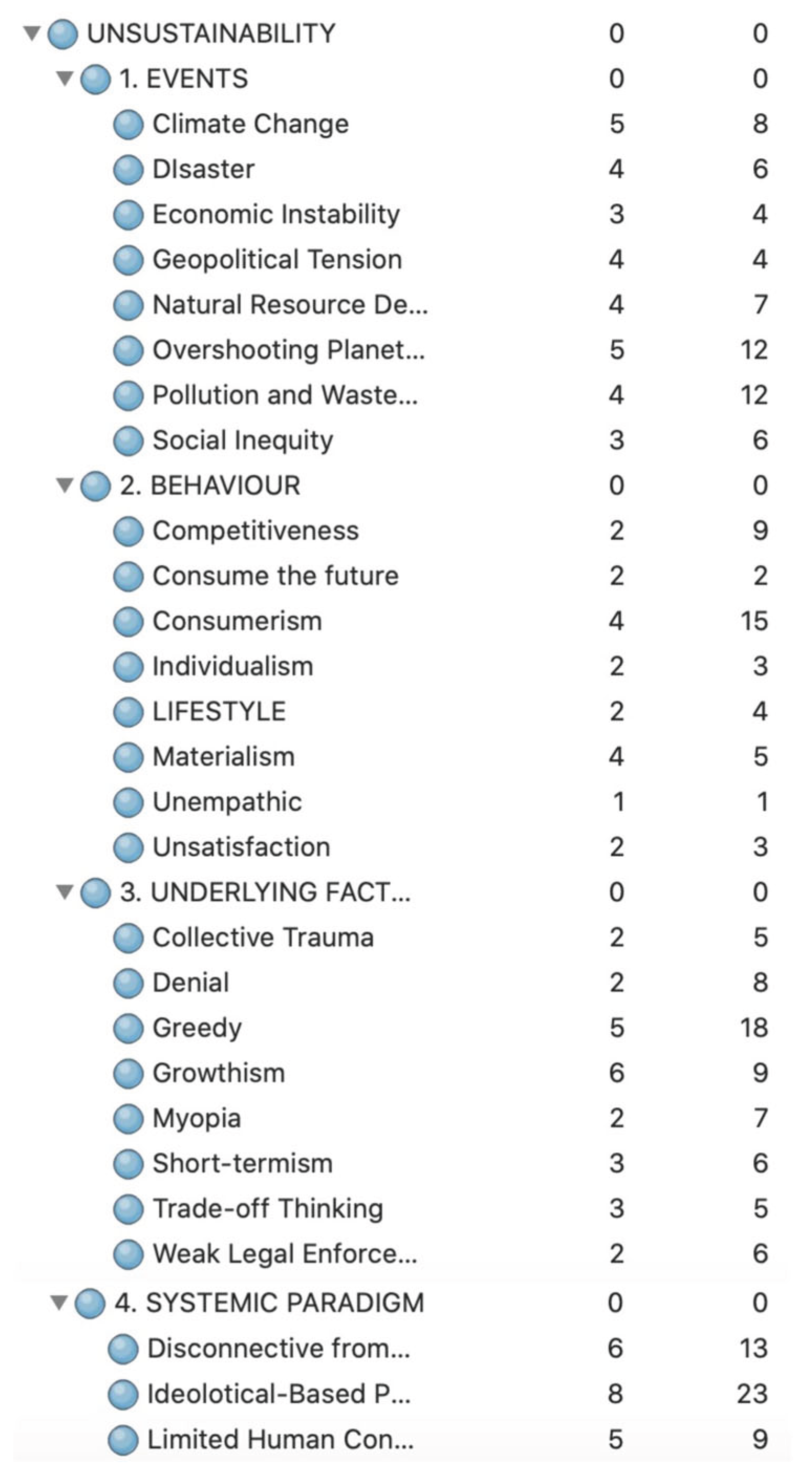

Following the initial coding, the dataset was revisited in a focused second cycle to refine and deepen the coding framework. Codes were inductively derived to capture nuance and complexity, leading to the final set of 27 distinct constructs.

Figure 2 visually represents the hierarchical coding structure, illustrating how the initial open codes were synthesized into these 27 constructs across. Each construct reflects a unique facet of the unsustainability crisis as perceived by the expert participants, ranging from observable phenomena such as climate change and disaster events to deeper systemic issues including ideological dominance and disconnect from nature.

3.2. Rationale of Thematic Categorization

The 27 codes identified through thematic coding were organized into four main categories: Events, Behavior, Underlying Factors, and Systemic Paradigm, as illustrated in

Figure 2. Each category groups related codes that share common characteristics, simplifying the complexity of qualitative data and highlighting key patterns [

34,

38]. These categories serve as conceptual frameworks that deepen the understanding of unsustainability. This clustering is supported by existing literature, providing theoretical justification for code inclusion within each category. Grounding the classification in prior research strengthens validity and clarifies the rationale, ensuring categories reflect recognized dimensions of unsustainability.

Events are defined by the Oxford English Dictionary (OED, 2023) as “something that happens or takes place, especially something significant or noteworthy; an incident, an occurrence.” In sustainability and climate studies, ‘events’ commonly denote notable natural and socio-environmental phenomena that signal disruptions to ecological and societal stability. For example, Ref [

43] explicitly links ‘events’ to climate-related phenomena such as droughts, storms, and hurricanes, which serve as direct manifestations of environmental perturbations. Similarly, Ref [

44] interprets ‘events’ as critical changes affecting natural resource dynamics and human-environment relationships. Ref [

45] conceptualizes events as a constellation of intensifying ecological crises (wildfires, floods, and droughts) that collectively reveal systemic environmental instability caused by anthropogenic actions. Moreover, Ref [

46] highlights that such events disproportionately impact vulnerable populations, exacerbating social inequalities and resource conflicts, a view supported by Ref [

47] that document significant socio-economic effects on local communities. Accordingly, codes including social inequity, pollution and waste accumulation, overshooting planetary limits, natural resource depletion, geopolitical tension, economic instability, disaster, and climate change are grouped under Events. This grouping reflects an understanding of these codes as interconnected phenomena that collectively represent the accelerating crisis of planetary instability and social vulnerability [

48,

49,

50].

Behavior, in contrast, refers to the observable actions of individuals or groups that directly influence ecological and social outcomes. Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior defines behavior as any measurable action, shaped by intentions, attitudes, and perceived social norms [

48]. In sustainability research, behavior encompasses individual and collective patterns that either promote or undermine sustainable development. Ref [

49] elaborates that behavior is shaped by complex psychological factors, including motivation, beliefs, and social pressures, and is reflected in habitual lifestyles and consumption patterns. Ref [

50] employs self-determination theory to explain how motivation influences sustainable resource use. Ref [

51] critiques unsustainable behavior as rooted in consumerism, materialism, and narrow self-interest, which drive excessive consumption and social fragmentation. In line with Ref [

52] which highlights how strong emotional attachment to material possessions (materialism) can provoke feelings of loss, thereby reinforcing unsustainable consumption habits. Accordingly, codes such as unsatisfaction, unemphatic, materialism, lifestyle, individualism, consumerism, consume the future, and competitiveness are classified under Behavior, representing critical drivers and expressions of unsustainability supported by psychological and sociological evidence [

49].

Meanwhile, Underlying Factors capture fundamental psychological, cultural, and structural drivers that implicitly influence behavior and institutional decision-making. Ref [

16,

53] defines short-termism as a cognitive bias favoring immediate gratification over long-term outcomes, coupled with a tendency to underestimate future consequences, which can lead to the neglect of environmental sustainability and the needs of future generations [

54]. Similarly, myopia, described by Ref [

17,

55] as the propensity to act in a ‘short-sighted’ manner by prioritizing immediate rewards while disregarding long-term impacts, exemplifies such cognitive constraints. Ref [

56,

57] identifies denial as a psychological defense mechanism that hinders recognition of and response to environmental degradation. Socio-cultural drivers include growthism, an ideological commitment to perpetual economic growth regardless of ecological limits [

58,

59,

60], and greed, reflecting cultural norms that valorize accumulation [

60,

61]. Collective trauma refers to shared historical psychological wounds that shape short-term, survival-oriented behaviors, as articulated by Ref [

62]. At the structural level, weak legal enforcement, as noted by Ref [

63,

64], denotes institutional failures in effectively regulating environmental harm, while trade-off thinking frames sustainability as an inevitable conflict between economic growth and environmental protection. Collectively, these codes represent Underlying Factors, encapsulating deeply entrenched cognitive, cultural, and systemic barriers to sustainability [

59,

62].

Finally, Systemic Paradigm refers to the deep-seated worldviews and ideological frameworks that shape societal organization, values, and relationships with nature. Ref [

15] explains that limited human consciousness reflects constrained ecological awareness, which impedes recognition of planetary boundaries and interconnectedness. Meanwhile, Ref [

65,

66] describes the disconnection from nature paradigm arising from anthropocentric views that instrumentalize nature and deny its intrinsic non-human values. The ideological-based political economy, as discussed by Ref [

58,

60,

67], refers to dominant economic systems, particularly capitalism and growthism, an economic-political framework prioritizing economic growth as the primary goal, often justifying environmental externalities as acceptable trade-offs. These systemic paradigms serve as foundational drivers perpetuating unsustainability by embedding specific values, institutional arrangements, and collective consciousness that resist transformative change. Such conceptualizations align with scholarly assertions that global environmental challenges are inseparable from prevailing value systems and patterns of thought [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Addressing these paradigms is therefore essential for fostering the deep transformations required for sustainable education [

68,

69]. This systemic paradigm and its implications will be examined in detail in Chapter 4.

3.3. Cross-Referencing Expert Views and Literature

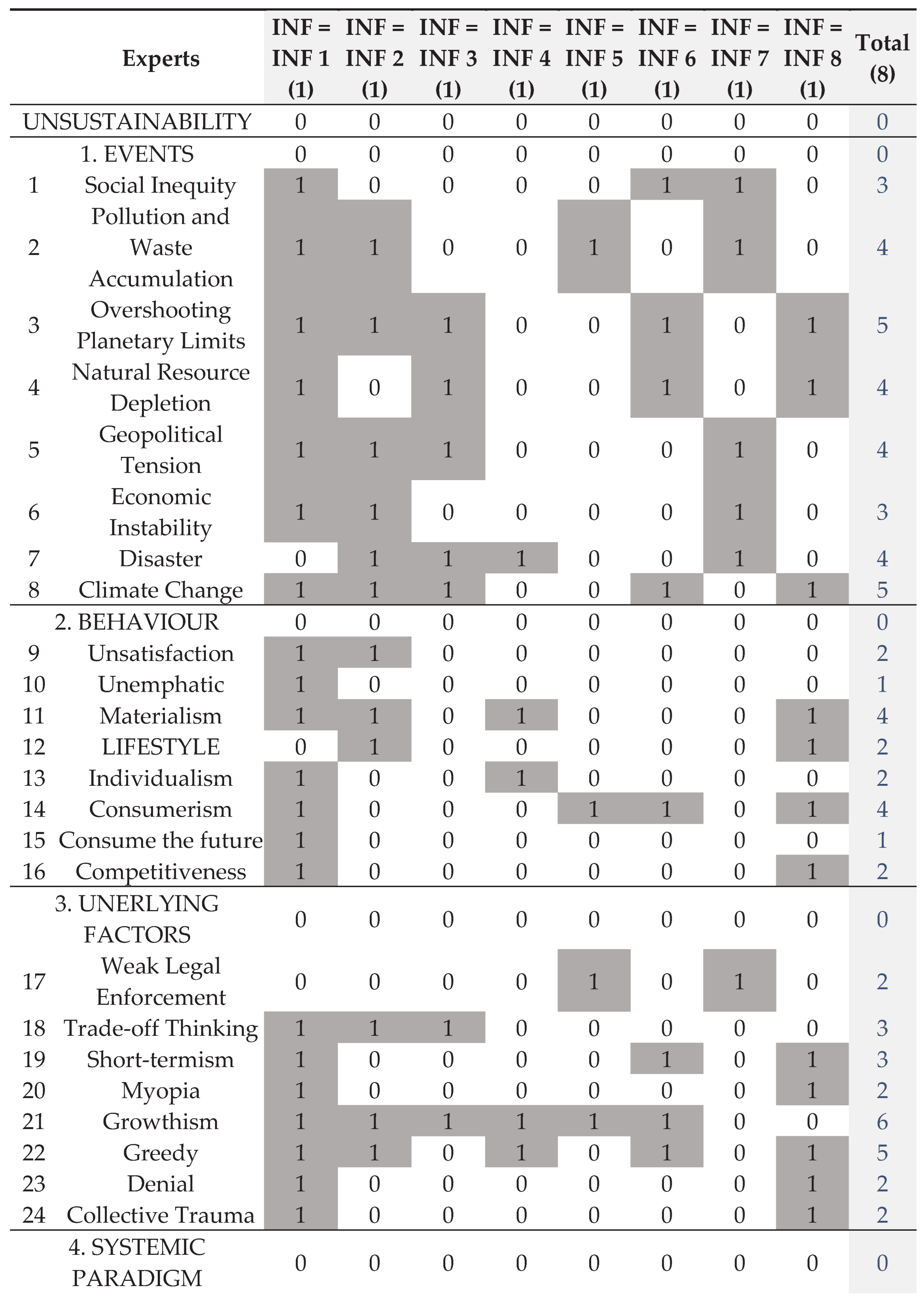

Triangulation in this study involved integrating multiple perspectives from experts with diverse backgrounds to verify data and findings. The frequency data presented in

Table 2 reveals how often each code was referenced, helping to identify the most commonly discussed factors across different domains. However, the significance of these codes lies not only in their frequency but in their contextual relevance to the systemic nature of unsustainability. Triangulation was further strengthened by existing literature, providing theoretical grounding, external validation [

34], and enhancing sensitivity to nuanced data aspects [

40].

In the Events category, codes such as overshooting planetary boundaries and climate change emerged as the most frequently cited, each referenced by five experts. As Expert 1 noted, “Disrupting the ecological balance either,” highlighting the critical need to address the overshooting of planetary boundaries. Expert 6 further emphasized, “Six out of nine planetary boundaries have already been surpassed,” pointing to the urgency of recognizing and respecting the Earth’s finite resources. In line with these concerns, Expert 2 shared, “Landslides are nature’s own way of seeking balance,” illustrating how environmental disasters can be seen as nature’s response to the imbalance created by human actions. These comments collectively highlight the feedback loop between human-induced unsustainability and ecological events, where disruptions to the Earth’s balance create immediate, visible consequences. These findings underscore the recognition of these phenomena as urgent and visible manifestations of environmental crises with global implications and the critical need for the maintenance of the Earth system [

70,

71].

Materialism and consumerism were most commonly referred to from the Behavior category, especially by the Business Practice and Environmental/Sustainability experts. These codes underscore how societal and individual behaviors, shaped by cultural norms and economic incentives, significantly contribute to unsustainable practices. Expert 1 remarked, “When we have a culture which is about consumerism, materialism, and individualism, this is also a factor of unsustainability”. This underscores the cultural aspects of unsustainability wherein social norms of consumption and personal enrichment undermine sustainability initiatives. Expert 8 added, “Overconsumption and the unwillingness to reduce our comfortable lifestyle contribute to the unsustainability crisis,” emphasizing how deeply ingrained cultural expectations of comfort and excess perpetuate unsustainable consumption patterns. This commentary is supported by Ref [

51] and Ref [

49] which both argue that these behaviors are key drivers of unsustainability, particularly in consumer-driven societies.

The Underlying Factors domain was also an important category with growthism being the most frequently referenced code, mentioned six times. Experts underscored that the cultural obsession with perpetual growth is a major barrier to sustainability. Expert 1 and Expert 2 both observed, “We suffer from a very big issue: we have this culture of never having enough,” thus illustrating the unsustainability of a growth driven culture. Expert 8 suggested, “We need to promote ‘you know when to stop,’” advocating for a shift in societal values away from continuous growth to create sustainable futures. These insights highlight how cultural values around consumption and growth form systemic barriers to sustainability, as echoed by Ref [

56,

58,

61,

72], which describe growthism as a key ideological driver of unsustainable economic practices.

Finally, in the Systemic Paradigm, ideological-based political economy was universally referenced by all eight experts, reinforcing its foundational role in shaping unsustainability narratives. This highlights the inextricable link between political and economic ideologies and unsustainable practices. As Expert 4 emphasized, “Our political and economic systems are ideologically structured to prioritize growth over sustainability, which must be abandoned.” Expert 7 further added, “When we talk about sustainability, it is inseparable from the current political economy system,” emphasizing that the current political economy framework must undergo a fundamental transformation to support long-term sustainability. This sentiment was echoed by Expert 8, who stated, “Capitalism must be challenged; if it is not, we will not be able to achieve sustainability. The ideology must change.” These concerns reflect a broader recognition that the current growth-based economic model, particularly capitalism, is inherently at odds with sustainability goals [

58,

59,

73].

This cross-referencing of expert views and literature validates the multi-layered nature of unsustainability, showing that it is not only the visible symptoms, such as pollution, climate change, and resource depletion, that require attention, but also the deeply ingrained systemic structures, behaviors, and ideologies that sustain unsustainable practices. The findings underscore the interconnectedness of environmental, social, and economic challenges, highlighting the need for a comprehensive, holistic approach. Sustainable transformation, as the data suggests, necessitates addressing these root causes by restructuring systemic paradigms, ranging from individual behaviors and cultural norms to global political and economic frameworks. Thus, the insights from this study emphasize the crucial role of transformative reform in reshaping worldviews and systems to foster sustainability at all levels.

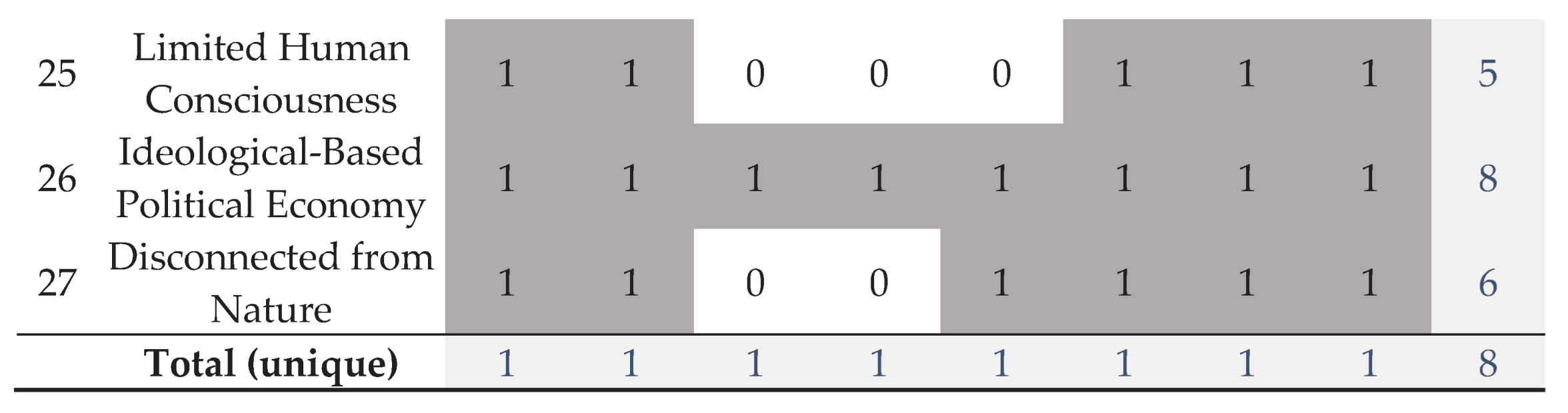

3.4. The Relationship Between Unsustainability Factors and the Role of Education

The relationship between unsustainability factors and the role of education, as identified through Research Question 3 (RQ3]. As seen in

Table 3, experts emphasize that education must evolve to confront deep-seated issues within current systems, addressing both cognitive and structural barriers.

The expert insights suggest that there are certain important realms to work on for education that take aim beneath the surface of the problematic paradigms that are keeping people and places locked into unsustainable situations. First, educational models need to break free of obsolete economic models ruled by competition and growth. Expert 1 stresses that these paradigms are key drivers of unsustainable consumption and inequality. The current education model continues to perpetuate the same thinking that has created these problems. As indicated by the expert insights, current education related to sustainability often fails to address the root causes of environmental problems by continuing to emphasize economic growth as a solution [

10]. The growth-based political-economic system remains entrenched in educational systems, reinforcing the mindset that has led to the current state of unsustainability. These models focus solely on economic growth may give low priority to ecological and social costs associated with them [

74].

Expert 6 also notes that the current educational system often creates a false consciousness. As Karl Marx introduced the term, false consciousness refers to a condition where individuals or groups fail to recognize or misunderstand their true social, political, or economic conditions. In line with the expert insight, education restricts critical understanding and maintains political and social dominance by elites, through the transmission of values and ideologies that preserve the status quo [

75]. This process perpetuates a form of social control, further entrenching the false consciousness that prevents students from questioning or challenging the systems of power that govern them, causing them to act as if there is nothing wrong simply because they do not know an alternative path [

60].

An equally crucial area identified in the expert insights is the disconnection from nature. This disconnection, deeply rooted in modern economic and cultural systems, helps explain why education often fails to produce individuals who act responsibly toward the environment. Education related to sustainability has been criticized for its anthropocentric approach, prioritizing human needs over ecological concerns and often overlooking the trade-offs between environmental, social, and economic sustainability [

24]. Highlighting this issue, but in relation to business education [

10], is the fact that economic growth is often taught to the exclusion of ecological balance.

Key insights from Expert 1 highlight how this disconnection from nature in education perpetuates the mindset that humans are separate from the environment. This perception, in turn, sustains unsustainable practices by disregarding the reality that humans are intricately connected to the environment. Expert 8 emphasizes that education should address this disconnection by promoting respect for nature and fostering behavioral change. Similarly, Expert 3 stresses the importance of environmental education as a means to help students recognize their role as part of nature. This approach would offer students a more accurate and holistic understanding of environmental issues. In addition, education is needed to underline that in order to have humans’ well-being, it is necessary to have a healthy planet, to overcome anthropocentrism and develop a holistic view that includes an awareness of the interdependence with the rest of the ecosystems [

76].

In addition to reconnecting with nature, addressing disconnection from self-awareness is equally important. Expert 1 highlights this disconnection from reality and self as a key factor in sustaining unsustainable behaviors. Education must foster wholeness, guiding students to recognize their role in the broader ecological system. Wholeness refers to a holistic, integrated understanding of both the self and the world, emphasizing the need for students to develop competencies that not only address sustainability from a knowledge-based perspective but also involve deeper, transformative thinking and holistic thinking [

21]. When students develop a sense of self-consciousness, they are more likely to adopt sustainable behaviors that align with their personal values and ecological responsibility [

77].

4. Discussion

4.1. Unravelling Root Causes of Unsustainability

The issue of unsustainability is often perceived as a collection of isolated global challenges, such as climate change, food insecurity, economic inequality, and health disparities. While these crises are interconnected, current global policies typically focus on responding to these events rather than addressing the systemic issues that fuel them. For instance, Ref [

44] mentioned the neo-classical approach to climate change promotes market-based solutions like carbon taxes and cap-and-trade policies, which treat the atmosphere as a tradable commodity. This approach frames climate change as a straightforward problem caused by the failure to charge greenhouse gas (GHG) emitters for the full cost of their emissions [

78]. The proposed remedy is to place a price on carbon [

79]. Similarly, the Paris Agreement also emphasizes market-based mechanisms, such as carbon trading, aiming to limit global temperature rise by encouraging countries to reduce their carbon emissions. However, whilst it is the case that many companies have adopted such methods, the solutions generated through these instruments are still insufficient when it comes to dealing with the underlying complexity, irreversibility, and uncertainties in the issue [

80]. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), moreover, have been criticized for focusing on issues rooted in the prevailing development paradigm, which may undermine their capacity to confront the climate emergency and the deep inequalities it intensifies [

81]. While the SDGs are a call for sustainable development that integrates the goals of economic growth, social equality, and environmental protection, it may also serve as an intermediary mediator to consolidate, rather than disrupt, unsustainable structures [

72].

Expanding on this criticism, the current study highlights that the real, sustainable solutions to these global challenges should and must be healing so much more than the immediate signs. At their core lie cognitive and systemic barriers, deep-rooted beliefs and structures that sustain harmful practices. Cognitive biases often prioritize short-term gains, while dominant economic models emphasize growth at the expense of environmental and social well-being. Therefore, tackling interconnected issues such as poverty, inequality, and climate change demands a fundamental paradigm shift that transforms the underlying systems perpetuating these problems, rather than merely mitigating their effects. The following subsections explore three critical paradigms identified through this study as the root causes of unsustainability.

4.1.1. Wholeness-Lessness / Existential Crisis Paradigm

Wholeness, as a concept, suggests the recognition of oneself as an integrated whole, where identity is shaped not only by internal aspects such as body and mind but also by one’s relationship with the external world [

52]. It involves a holistic acceptance of one’s entire being, acknowledging both intrinsic value and meaning, and transforming these insights into existential strength to lead a more fulfilled and purposeful life [

82]. In the context of positive psychology, human existentialism tackles the core questions about human existence, such as: What constitutes the "good life"? What makes life meaningful? And how can individuals achieve true happiness? These fundamental inquiries not only foster a deeper understanding of human potential but also guide individuals toward achieving a sense of wholeness [

83].

The wholeness-lessness paradigm, or existential crisis, indicates a deep disconnection from deeper values that offer meaning and direction. In materialistic and individualistic and consumerist societies, there are constant attempts to being involved in seeking validation from the things, power, status, consumer goods, career success, retaining status or social status which results in serious existential emptiness [

15]. This crisis of meaning manifests in unsustainable behaviors, such as excessive consumption and greed, which drive global challenges such as climate change, resource depletion, environmental degradation, and economic inequality while exacerbating poverty. It is important to note that greed is not an inherent aspect of human nature; rather, it is a by-product of modern socio-economic behaviors, which are unsustainable and have led to humanity’s alienation from more harmonious ways of living with nature [

84]. Likewise, overconsumption becomes a coping mechanism to fill the existential void created by disconnection from deeper spiritual and ethical values. When overconsumption is magnified on a global scale, it intensifies environmental destruction and deepens societal divides, amplifying the challenges of sustainability. Research indicates that shifts in consumption patterns often occur in response to economic prosperity, where increasing income and the availability of secular alternatives to traditional spiritual fulfilment further fuel these unsustainable behaviors [

85]. This deepened consumption culture only exacerbates global challenges, including unsustainable economic growth, resource depletion, and ecological collapse.

To address this existential crisis, it is essential to reconnect individuals with a sense of wholeness, helping them realize their interconnectedness with society and the natural world. This vision allows people to transcend superficial materialism and realize spiritual and moral values through the realization of community welfare and health of the ecology. The education system has a significant role to play in giving values of knowledge, humanity, ethics to enable them to get rid of their unhealthy consumption practices [

21].

4.1.2. Disconnection from Nature and Anthropocentric Perspective

The disconnection from nature, rooted in anthropocentrism, is, thus, one among the main paradigm causing the global challenges. Anthropocentrism places humans at the center of the universe, viewing nature solely as a resource to be exploited for human benefit, often disregarding its intrinsic value and ecological role [

65]. As Ref [

86] points out, human-centeredness, per se, is not a problem; it is the arbitrary primacy granted humans when non-human interests are sidelined that becomes problematic. This becomes particularly dangerous when anthropocentrism is seen as an explicit or arbitrary bias, focusing only on human interests while neglecting those of other species. This perspective reflects a form of "hubris" or arrogance, where nature is regarded merely as a resource for human use, without moral consideration or respect for non-human life [

87]. These types of attitudes have been associated to the acceleration of environmental destruction and species loss, as they tend to disregard the intrinsic value of non-human entities [

87].

In history, with the development of industrialization, globalization and urbanization, human society has become increasingly alienated from nature and heavily dependent on technology and system, which may weaken the direct relationship with the natural environment [

88]. This vision has resulted in an extreme dichotomy between humans in one sphere, and nature in another [

89].

The dichotomy from nature weakens humans’ sense of attachment, empathy, and responsibility toward the natural world. When people perceive themselves as separate from nature, they tend to view it merely as a resource to be exploited without limits. This detachment facilitates the rise of human greed, the drive to maximize short-term benefits and material gains from natural resources, without regard for long-term ecological consequences [

84]. As a result, ethical and ecological values that might restrain excessive exploitation diminish, leading to more aggressive depletion and environmental harm. This creates a vicious cycle: the deeper the disconnect from nature, the stronger the greed and exploitation become, further damaging ecosystems and reinforcing the sense of separation.

To address these interconnected issues, a shift towards non-anthropocentric frameworks is essential. These frameworks emphasize equal consideration for all beings, fostering a more sustainable and balanced relationship with the environment [

90]. By extending moral consideration to non-human entities and recognizing their intrinsic value and ecological roles, we can build a more ethical relationship with nature. Such a paradigm shift acknowledges the interconnectedness of all life forms, emphasizing that human well-being is intrinsically tied to the health of ecosystems. Psychological interventions, such as promoting superordinate identities that include both humans and nonhumans, could help mitigate the biases inherent in anthropocentrism [

90]. This approach would encourage a more inclusive, harmonious worldview that respects and values all living beings.

Building upon this, moving beyond anthropocentrism is therefore not merely a philosophical shift but an urgent necessity for a sustainable future. Adopting an eco-centric perspective would not only support sustainable health systems but also directly address the root causes of global challenges like environmental degradation and biodiversity loss, fostering a deeper respect for nature and ecological balance [

91].

4.1.3. Ideological-Based Political Economy System

Well-being is currently embedded within a societal growth model institutionalized within the ideological-based political economy system, which heavily emphasizes capitalist structures that prioritize economic expansion [

92]. Growth-oriented political economics, such as capitalism, plays a critical role in driving many global challenges, including climate change, economic inequality, social injustice, and pressure on natural resources [

10,

11,

12]. Capitalism, with its focus on continuous economic growth, profit maximization, and market expansion, incentivizes behaviors that exploit natural resources, deepen poverty, and exacerbate social disparities [

58,

59,

60,

67]. The system’s emphasis on short-term profits and quantitative growth results in unsustainable consumption patterns, pollution, and the overexploitation of ecosystems [

59,

67]. As Ref [

89,

93] argues, capitalism’s political economy is rooted in an aggressive accumulation strategy: Cheap Nature. For capitalism, nature is “cheap” in two senses: it is made “cheap” in price, and simultaneously degraded in an ethical-political sense, which facilitates its exploitation. These two elements are intertwined in every major capitalist transformation over the past five centuries.

Given these systemic challenges, this study highlights the critical need to promote alternative paths within political-economic systems and to move beyond the dominant economic model. As emphasized by Ref [

94], fostering diversity in economic thought and social values is crucial for effectively addressing complex issues such as climate change. Despite capitalism's dominant role, there remains insufficient exploration of alternatives to this growth-based economic system, such as steady-state economics [

95], the doughnut economy [

96], ecological economics [

97] or degrowth paradigm [

98] all of which emphasize well-being over infinite growth. Just as biodiversity loss undermines the stability and adaptability of ecosystems, the absence of diverse political-economic systems limits our capacity to effectively address complex global challenges including climate change, social inequality, and ecological degradation [

94]. Therefore, moving beyond the prevailing growth-oriented model is essential. A continued focus on growth alone no longer adequately addresses the ecological justice issues confronting the world today, highlighting the urgent need to explore and adopt alternative economic frameworks [

99].

The reliance on growth-oriented economics limits the broader goal of achieving well-being for all, as it perpetuates ecological degradation and social inequality. According to Ref [

92], well-being must be redefined beyond growth metrics and should focus on a more equitable, sustainable distribution of resources. This shift is particularly critical in the context of postgrowth, a concept that rejects the reliance on economic growth as the primary goal of development and well-being. Postgrowth challenges the assumption that perpetual growth is the solution to societal and economic problems, proposing instead a model focused on sustainability and the flourishing of human and ecological systems [

92]. Ref [

100] suggests that a post-growth approach to education could help prepare students for a future no longer reliant on infinite economic expansion, focusing on the development of their ecological literacy.

4.2. Current Sustainability-Centric Education

The phenomenon of unsustainability is deeply rooted in systemic factors that continue to shape and exacerbate global challenges. In this context, education emerges as a critical force in addressing these foundational issues. Yet the critique of mainstream education remains in terms of sustainability education that is often at best a superficial approach to these difficult matters. The results of this study illuminate central deficiencies in the current education system's addressing of unsustainability. Education remains anchored in outdated economic models focused on growth, which perpetuate unsustainable consumption and inequality. Additionally, it fosters a "false consciousness," limiting critical thinking and reinforcing existing power structures. Traditional educational approaches, including sustainability education, are still grounded in capitalist principles, for the most part, designed to sustain the status quo [

101]. For this reason, much of current education continues to propagate the same mindset that has contributed to the sustainability crisis.

Several educational models have emerged to promote sustainability, including Environmental Education (EE), Education for Sustainability (EfS), Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), and Education for Sustainable Development Goals (ESDG). While effective in raising awareness, these models often focus on knowledge transmission rather than fostering the deeper value-based and ethical transformations necessary to address the root causes of unsustainability. Notably, ESDG emphasizes “inclusive and sustainable economic growth” but frequently overlooks long-term ecological impacts and systemic environmental challenges [

24]. ESD has also moved further from what constituted traditional Environmental Education, which was concentrated on the preservation of nature and nature protection areas, to a broader picture of human well-being, social justice and fair distribution of resources. Such a focus allows for the attenuation of the emphasis on ecological issues, and ecological justice, and side-lines a more anthropocentric lens that values nature only in so far as human interests and economic profits can be protected over nature’s inherent worth [

74]. EfS has also faced criticism for emphasizing systemic reforms without adequately promoting individual behavioral change, which limits its practical effectiveness [

102,

103]. Furthermore, most of these models are also an extension of anthropocentrism that does not instill an eco-centric perspective which acknowledges the inter-relatedness of all life [

104].

Traditional educational approaches, including those centered on sustainability, often fall short in driving urgent transformation because they avoid confronting entrenched political power structures and vested interests that maintain unsustainable systems [

101]. The above research highlights the role of value-based education that goes beyond cognitive knowledge to challenge the fundamental values, ethics, and worldviews sustaining unsustainable behaviors, directly addressing issues such as fragmentation, anthropocentrism, and growth-driven economic systems.

4.3. Moving Forward: Education for Sustainable Futures

To effectively address the pressing global challenges such as climate change, environmental degradation, and the deterioration of public health, education must extend beyond traditional models that focus solely on technical solutions and knowledge transfer. The study’s findings indicate that these challenges are deeply rooted in underlying worldviews, which shape human behavior, societal structures, and policy decisions. Therefore, educational approaches must engage with these deep-seated paradigms, including materialism, individualism, and anthropocentrism, which perpetuate unsustainable behaviors. By shifting educational practices to address these core issues, we can foster a more transformative and holistic approach to sustainability.

This research offers several critical recommendations based on the systemic paradigms identified in the study. These recommendations emphasize the importance of incorporating value-driven, holistic approaches into education, aimed at addressing the root causes of unsustainability.

Addressing Wholeness-lessness through Value-Based Education: A key finding of the study is the importance of addressing wholeness-lessness, which is linked to fragmented identities and collective disorientation. This crisis of meaning often leads individuals to seek fulfilment through materialism and consumerism, exacerbating environmental degradation and social inequality. To address this, education systems must integrate value-based education that emphasizes human dignity, relationships, and a connection to the natural world. Educators should guide students to recognize the intrinsic value of nature and humanity, focusing on well-being that stems from connection to self, community, and the environment, rather than external possessions. Ref [

105] emphasizes the importance of values-based and ethics-driven education to guide integrity and responsibility in decision-making. By fostering ethics and empathy, education can encourage sustainable lifestyles that promote long-term ecological and social harmony [

21,

106].

Moving Beyond Anthropocentrism: Embracing Eco-Centric Worldviews: Another significant driver of unsustainability identified in the study is anthropocentrism, the human-centered worldview that places humanity above nature. This perspective contributes to exploitation and unsustainable environmental practices. Education must shift towards eco-centric approaches, emphasizing the interconnectedness of all life forms and ecosystems. Sustainability education should teach students that sustainability is not only about human survival but about maintaining the balance of the entire ecosystem. Ref [

104] argues for a shift from human-centered to earth-centered thinking, where the health of the planet is prioritized alongside human needs. Building on this, Ref [

107] also argues that education should internalize eco-centric and eco-pedagogical principles, creating a transformative paradigm in sustainability education to address environmental and social crises. Furthermore, Ref [

108] highlights that the inclusion of biocentric ethics within education fosters respect for all life forms and nurtures ecological empathy.

Moving Beyond Dominant Political-Economic Systems: Exploring Post-Growth Models: Finally, the study identifies global political-economic systems, particularly capitalism with its emphasis on perpetual growth, as a primary driver of unsustainability. This system encourages the exploitation of natural resources and increases social inequality. Education must help students explore alternative economic models that prioritize sustainability, equity, and long-term well-being over unchecked growth. Ref [

10,

100,

104] advocate for critically assessing capitalist paradigms and exploring post-growth models, such as steady state de-growth, which focus on restoring ecosystems and creating sustainable livelihoods. Given this perspective, it becomes increasingly crucial for education to integrate various disciplines and learning methods in order to enhance environmental literacy, fostering a comprehensive understanding of ecological issues and solutions [

109].

5. Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive understanding of the underlying causes of unsustainability, revealing how systemic structures, behaviors, and worldviews perpetuate global crises. A key finding is the identification of a four-layer hierarchy of unsustainability: Events → Behavior → Underlying Factors → Systemic Paradigm. The study shows that crises such as climate change, resource depletion, and socio-economic inequality are not isolated issues but symptoms of deeper, more pervasive systemic problems. To act on these crises, it’s necessary to look beyond surface fixes and grapple with the deeper layer of systems that support them. These superficial matters are symptomatic of the root level worldviews and value systems that condition how people think and act, how societies function and how institutions operationalize.

The study identifies three fundamental systemic paradigms driving unsustainability: the Wholeness-lessness/Existential Crisis Paradigm, the Disconnection from Nature and Anthropocentric Perspective, and the Ideological-Based Political Economy System. The Wholeness-lessness Paradigm is based on a crisis of meaning that drives people to find fulfilment through materialism and consumerism, exacerbating environmental degradation and social inequality. The Disconnection from Nature paradigm highlights the anthropocentric worldview, which treats nature as a resource to be exploited for human benefit, leading to environmental harm. The Ideological-Based Political Economy System, particularly capitalism, has as its main goal never ending economic growth, maximization of profit and market growth, and at all costs, at the expense of ecology and social justice.

Addressing such cultural norms, the research highlights the importance of education in catalyzing change. ESD needs to move beyond knowledge transfer and deal squarely with the root causes of unsustainability. It should help to develop critical awareness, eco-empathy, and systemic thought, that is, the capability to criticize and change the worldviews, practices, and policies that support unsustainable practices. Education needs to call attention to the underlying ideologies of prevailing economic systems and for alternative models, such as steady-state economics, the doughnut economy, ecological economics, or degrowth paradigm, which favor ecological balance and social equity over unfettered growth. Additionally, education should reconnect individuals with nature, instilling a deeper understanding of humanity’s interdependence with the environment and fostering sustainable behaviors at both individual and societal levels.

In the end, the results of this study demand a radical shift in education to eliminate the primary causes of unsustainability. To truly make a difference, education should go beyond sustainability literacies and focus on questioning the underlying paradigms that hinder sustainable futures. Education must nurture a generation of critical thinkers, environmental caretakers, and systems thought leaders who can serve as a powerful force for change to address global challenges such as health pandemics, climate change, resource depletion, and social equity, ensuring that a sustainable future is possible for all.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.E.D.; methodology, D.E.D.; investigation, D.E.D.; data curation, D.E.D.; writing—original draft preparation, D.E.D.; supervision, J.W. and N.A.A.; validation, J.W. and N.A.A.; writing—review and editing, J.W., N.A.A., and S.S.; formal analysis, S.S.; resources, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors also declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ghosh, E.; Pearson, L.J. Rethinking Economic Foundations for Sustainable Development: A Comprehensive Assessment of Six Economic Paradigms Against the SDGs. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4567. [CrossRef]

- WHO World Health Statistics 2024: Monitoring Health for the SDGs; World Health Organization (WHO), 2024;

- OPHI; UNDP Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2024: Poverty amid Conflict; United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), University of Oxford., 2024;

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024; FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO;, 2024; ISBN 978-92-5-138882-2.

- 2025; 5. FSIN; GNAFC 2025 Global Report on Food Crises; Food Security Information Network; Global Network Against Food Crises, 2025;

-

The Global Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Brondízio, E.S., Settele, J., Díaz, S., Ngo, H.T., Eds.; Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES): Bonn, 2019; ISBN 978-3-947851-20-1.

- WWF Living Planet Report 2024 – A System in Peril.; WWF International: Gland, Switzerland, 2024;

- Benton, T.G.; Bieg, C.; Harwatt, H.; Pudasaini, R.; Wellesley, L. Food System Impacts on Biodiversity Loss. Chatham House 2021.

- UNEP Ecosystem Restoration for People, Nature and Climate: Becoming #GenerationRestoration; United Nations: Erscheinungsort nicht ermittelbar, 2021; ISBN 978-92-807-3864-3.

- Kopnina, H.; Hughes, A.C.; Zhang, R. (Scarlett); Russell, M.; Fellinger, E.; Smith, S.M.; Tickner, L. Business Education and Its Paradoxes: Linking Business and Biodiversity through Critical Pedagogy Curriculum. British Educational Res J 2024, 50, 2712–2734. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P. (Tima); Grewatsch, S.; Sharma, G. How COVID-19 Informs Business Sustainability Research: It’s Time for a Systems Perspective. J Management Studies 2021, 58, 602–606. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Ibrahim, R.L.; Raimi, L.; Omokanmi, O.J.; S Senathirajah, A.R.B. Balancing Growth and Sustainability: Can Green Innovation Curb the Ecological Impact of Resource-Rich Economies? Sustainability 2025, 17, 4579. [CrossRef]

- Emissions Trends and Drivers. In Climate Change 2022 - Mitigation of Climate Change; Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change (Ipcc), Ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2023; pp. 215–294 ISBN 978-1-00-915792-6.

- Ahmed, Z.; Zhang, B.; Cary, M. Linking Economic Globalization, Economic Growth, Financial Development, and Ecological Footprint: Evidence from Symmetric and Asymmetric ARDL. Ecological Indicators 2021, 121, 107060. [CrossRef]

- Høyer, K.G.; Næss, P. The Ecological Traces of Growth: Economic Growth, Liberalization, Increased Consumption—and Sustainable Urban Development? Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 2001, 3, 177–192. [CrossRef]

- Gabaix, X.; Laibson, D. Myopia and Discounting; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, 2017; p. w23254;.

- Mella, P.; Pellicelli, M. How Myopia Archetypes Lead to Non-Sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 10, 21. [CrossRef]

- Vlek, C.; Steg, L. ⊡ Human Behavior and Environmental Sustainability: Problems, Driving Forces, and Research Topics. Journal of Social Issues 2007, 63, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Onel, N.; Mukherjee, A. The Effects of National Culture and Human Development on Environmental Health. Environ Dev Sustain 2014, 16, 79–101. [CrossRef]

- Elgin, D. Building a Sustainable Species-Civilization. Futures 1994, 26, 234–245. [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Akura, G. Addressing the Wicked Problems of Sustainability Through Consciousness-Based Education. Journal of Health and Environmental Research 2017.

- Csillag, S.; Király, G.; Rakovics, M.; Géring, Z. Agents for Sustainable Futures? The (Unfulfilled) Promise of Sustainability at Leading Business Schools. Futures 2022, 144, 103044. [CrossRef]

- Snelson-Powell, A.C.; Grosvold, J.; Millington, A.I. Organizational Hypocrisy in Business Schools with Sustainability Commitments: The Drivers of Talk-Action Inconsistency. Journal of Business Research 2020, 114, 408–420. [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. Education for Sustainable Development Goals (ESDG): What Is Wrong with ESDGs, and What Can We Do Better? Education Sciences 2020, 10, 261. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.; Kulshreshtha, A.K. A STUDY OF ENVIRONMENTAL VALUE AND ATTITUDE TOWARDS SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT AMONG PUPIL TEACHERS. 2012.

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook; Third edition.; SAGE Publications, Inc: Thousand Oaks, Califorinia, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4522-5787-7.

- Crittenden, V.L.; Peterson, R.A. Ruminations about Making a Theoretical Contribution. AMS Rev 2011, 1, 67–71. [CrossRef]

- Borges, R.M. Knowledge from Knowledge: An Essay on Inferential Knowledge. Doctoral dissertation, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey 2015.

- On Interviewing “Good” and “Bad” Experts. In Interviewing Experts; Gläser, J., Laudel, G., Eds.; Research methods series; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke London, 2009 ISBN 978-0-230-22019-5.

- Meuser, M.; Nagel, U. The Expert Interview and Changes in Knowledge Production. In Interviewing Experts; Bogner, A., Littig, B., Menz, W., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, 2009; pp. 17–42 ISBN 978-1-349-30575-9.

- The Theory-Generating Expert Interview: Epistemological Interest, Forms of Knowledge, Interaction. In Interviewing Experts; Bogner, A., Menz, W., Eds.; Research methods series; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke London, 2009 ISBN 978-0-230-22019-5.

- Witzel, A. The Problem-Centered Interview. 2000.

- Between Scientific Standards and Claims to Efficiency: Expert Interviews in Programme Evaluation. In Interviewing Experts; Wroblewski, A., Leitner, A., Eds.; Research methods series; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke London, 2009 ISBN 978-0-230-22019-5.

- Kuckartz, U. Qualitative Text Analysis: A Guide to Methods, Practice & Using Software; SAGE: Los Angeles, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4462-6775-2.

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology; 2. ed., [ Nachdr.].; Sage Publ: Thousand Oaks, Calif., 2004; ISBN 978-0-7619-1544-7.

- Albig, W. Content Analysis in Communication Research. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 1952, 283, 197–198. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, K.; Bazeley, P. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo; 3. edition.; Sage: Los Angeles London New Delhi Singapore Washington, DC Melbourne, 2019; ISBN 978-1-5264-4993-1.

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; 2nd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4462-4736-5.

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research; Edition 5.; Sage: Los Angeles, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4462-6778-3.

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research.

- Creswell, J.W.; Miller, D.L. Determining Validity in Qualitative Inquiry. Theory Into Practice 2000, 39, 124–130. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 2014, 4th ed.

- Chew Hung, C. Climate Change Education: Knowing, Doing and Being; 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, 2022; ISBN 978-1-00-309380-0.

- Titumir, R.A.M.; Afrin, T.; Islam, M.S. Natural Resource Degradation and Human-Nature Wellbeing: Cases of Biodiversity Resources, Water Resources, and Climate Change; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; ISBN 978-981-19866-0-4.

- Thunberg, G. The Climate Book; Penguin Press: New York, 2023;

- Santelices Spikin, A.; Rojas Hernández, J. Climate Change in Latin America: Inequality, Conflict, and Social Movements of Adaptation. Latin American Perspectives 2016, 43, 4–11. [CrossRef]

- Muyambo, F.; Belle, J.; Nyam, Y.S.; Orimoloye, I.R. Climate Change Extreme Events and Exposure of Local Communities to Water Scarcity: A Case Study of QwaQwa in South Africa. Environmental Hazards 2024, 23, 405–422. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behaviour: Reactions and Reflections. Psychology & Health 26(9), 1113–1127. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.; Heidrich, O.; Cairns, K. Psychological Factors to Motivate Sustainable Behaviours. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Urban Design and Planning 2014, 167, 165–174. [CrossRef]

- Baxter, D.; Pelletier, L.G. The Roles of Motivation and Goals on Sustainable Behaviour in a Resource Dilemma: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2020, 69, 101437. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Prosperity without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet; Earthscan: London ; Sterling, VA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-84407-894-3.

- Belk, R.W. Possessions and the Extended Self. Journal of Consumer Research 1988, 15, 139–168. [CrossRef]

- Mella, P. Systems Thinking; Perspectives in Business Culture; Springer Milan: Milano, 2012; Vol. 2; ISBN 978-88-470-2564-6.

- Gattig, A.; Hendrickx, L. Judgmental Discounting and Environmental Risk Perception: Dimensional Similarities, Domain Differences, and Implications for Sustainability. Journal of Social Issues 2007, 63, 21–39. [CrossRef]

- Gattig, A. Intertemporal Decision Making: Studies on the Working of Myopia; ICS dissertation series; Rijksuniv: Groningen, 2002; ISBN 978-90-5170-603-1.

- Washington, H.; Kopnina, H. Discussing the Silence and Denial around Population Growth and Its Environmental Impact. How Do We Find Ways Forward? World 2022, 3, 1009–1027. [CrossRef]

- Oreskes, N.; Conway, E.M. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming; Bloomsbury Press: New York, Berlin, London, 2010;

- Kallis, G.; Kostakis, V.; Lange, S.; Muraca, B.; Paulson, S.; Schmelzer, M. Research On Degrowth. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2018, 43, 291–316. [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.E. Beyond Growth: The Economics of Sustainable Development. Beacon Press. 1996.

- Hamilton, C. Growth Fetish; Allen & Unwin: Sydney, 2003; ISBN 978-1-74114-078-1.

- Fromm, E. To Have or to Be?; Continuum: London, 2007; ISBN 978-0-8264-1738-1.

- Alexander, J.C. Toward a Theory of Cultural Trauma. In Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity; Macmillan Education UK: London, 2017; pp. 375–386 ISBN 978-1-137-61120-8.

- Norton, B.G. Sustainability: A Philosophy of Adaptive Ecosystem Management; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 2005; ISBN 978-0-226-59519-1.

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J. Beyond the Limits: Confronting Global Collapse or a Sustainable Future; Chelsea Green Pub: Chelsea, Vt, 1992; ISBN 978-0-930031-55-8.

- Kopnina, H.; Washington, H.; Taylor, B.; J Piccolo, J. Anthropocentrism: More than Just a Misunderstood Problem. J Agric Environ Ethics 2018, 31, 109–127. [CrossRef]

- Washington, H.; Piccolo, J.J.; Kopnina, H.; O’Leary Simpson, F. Ecological and Social Justice Should Proceed Hand-in-Hand in Conservation. Biological Conservation 2024, 290, 110456. [CrossRef]

- Daly, H. Growthism: Its Ecological, Economic and Ethical Limits.

- Sterling, S. Learning and Sustainability in Dangerous Times: The Stephen Sterling Reader; 1st ed.; Agenda Publishing, 2024; ISBN 978-1-78821-692-0.

- Sterling, S. Learning for Resilience, or the Resilient Learner? Towards a Necessary Reconciliation in a Paradigm of Sustainable Education. Environmental Education Research 2010, 16, 511–528. [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Broadgate, W.; Deutsch, L.; Gaffney, O.; Ludwig, C. The Trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration. The Anthropocene Review 2015, 2, 81–98. [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; De Vries, W.; De Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary Boundaries: Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [CrossRef]

- Marouli, C. Sustainability Education for the Future? Challenges and Implications for Education and Pedagogy in the 21st Century. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2901. [CrossRef]

- Hanaček, K.; Roy, B.; Avila, S.; Kallis, G. Ecological Economics and Degrowth: Proposing a Future Research Agenda from the Margins. Ecological Economics 2020, 169, 106495. [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. Education for Sustainable Development (ESD): The Turn Away from ‘Environment’ in Environmental Education? Environmental Education Research 2012, 18, 699–717. [CrossRef]

- Kann, M.E. Political Education and Equality: Gramsci Against “False Consciousness.” Teaching Political Science 1981, 8, 417–446. [CrossRef]

-

Transforming Education for Sustainability: Discourses on Justice, Inclusion, and Authenticity; Rivera Maulucci, M.S., Pfirman, S., Callahan, H.S., Eds.; Environmental Discourses in Science Education; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; Vol. 7; ISBN 978-3-031-13535-4.

- Fuchs, K. The Relationship between Academic Performance and Environmental Sustainability Consciousness: A Case Study in Higher Education. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism 2021, Volume XII, Winter. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R.D.; Hackler, D. Economic Doctrines and Approaches to Climate Change Policy. 2010.

- Mattauch, L.; Hepburn, C. Climate Policy When Preferences Are Endogenous-and Sometimes They Are. Midwest Stud Philos 2016, 40, 76–95. [CrossRef]

- Farmer, J.D.; Hepburn, C.; Mealy, P.; Teytelboym, A. A Third Wave in the Economics of Climate Change. Environ Resource Econ 2015, 62, 329–357. [CrossRef]

- Villavicencio Calzadilla, P. The Sustainable Development Goals, Climate Crisis and Sustained Injustices. Oñati Socio-Legal Series 2021, 11, 285–314. [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.P. From Shame to Wholeness An Existential Positive Psychology Perspective. 2018.

- Wong, P.T.P. Existential Positive Psychology. International Journal of Existential Psychology & Psychotherapy 2016, Volume 6, Issue 1.

- Gowdy, J.M. Hunter Gatherers and the Crisis Of Civilization. Annals of the Fondazione Luigi Einaudi: An interdisciplinary journal of economics, history and political science: LV, 1, 2021 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hirschle, J. “Secularization of Consciousness” or Alternative Opportunities? The Impact of Economic Growth on Religious Belief and Practice in 13 European Countries. Scientific Study of Religion 2013, 52, 410–424. [CrossRef]

- Hayward, T. Anthropocentrism: A Misunderstood Problem. 1997.

- Washington, H.; Piccolo, J.; Gomez-Baggethun, E.; Kopnina, H.; Alberro, H. The Trouble with Anthropocentric Hubris, with Examples from Conservation. Conservation 2021, 1, 285–298. [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; Graumlich, L.; Steffen, W.; Crumley, C.; Dearing, J.; Hibbard, K.; Leemans, R.; Redman, C.; Schimel, D. Sustainability or Collapse: What Can We Learn from Integrating the History of Humans and the Rest of Nature? AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment 2007, 36, 522–527. [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.W. Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital; Verso: London; NewY ork, 2015;

- Gradidge, S.; Zawisza, M. Toward a Non-Anthropocentric View on the Environment and Animal Welfare: Possible Psychological Interventions. Animal Sentience 2020, 4. [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H.; Randers, J.; Meadows, D.L. The Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update; Reprint.; Earthscan: London, 2009; ISBN 978-1-84407-144-9.

- Büchs, M.; Koch, M. Postgrowth and Wellbeing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-59902-1.

- Moore, J.W. Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism; PM Press: Oakland, CA, 2016;

- O’Hara, S. Living in the Age of Market Economics: An Analysis of Formal and Informal Institutions and Global Climate Change. World 2025, 6, 35. [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.E. Steady-State Economics: Second Edition with New Essays; Island Press, Washington, DC, 1991; ISBN 1 55963 072 8.

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist.; Chelsea Green Publishing, 2017;

- Costanza, R. Ecological Economics 1; Elsevier, 2008;

- Hickel, J. Less Is More How Degrowth Will Save the World; William Heinemann London, 2020;

- Lynch, M.J.; Long, M.A.; Stretesky, P.B. Green Criminology and Green Theories of Justice: An Introduction to a Political Economic View of Eco-Justice; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-28572-2.

- White, R.J. Imagining Education beyond Growth: A Post-Qualitative Inquiry into the Educational Consequences of Post-Growth Economic Thought. Curric Perspect 2024, 44, 539–549. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, C.J.; Thierry, A.; Rowlandson, W.; Steinberger, J.K. From Publications to Public Actions: The Role of Universities in Facilitating Academic Advocacy and Activism in the Climate and Ecological Emergency. Front. Sustain. 2021, 2, 679019. [CrossRef]

- Tilbury, D. Whole-School-Approach to Sustainability in Schools: A Review 2022.

- Fien, J. Learning to Care: Education and Compassion. Aust. J. environ. educ. 2003, 19, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S. Learning for Resilience, or the Resilient Learner? Towards a Necessary Reconciliation in a Paradigm of Sustainable Education. Environmental Education Research 2010, 16, 511–528. [CrossRef]